Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit: Chapters 12 - 22

message 151:

by

Sara

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Oct 02, 2020 11:06AM

I suppose even Amy might have dreams of her own that do not include serving others or pleasing them with her marriage choice. It is obvious she does not care for him in any personal way. It will be interesting to see if he has a role in the coming story. Dickens seldom introduces even a minor character without purpose.

I suppose even Amy might have dreams of her own that do not include serving others or pleasing them with her marriage choice. It is obvious she does not care for him in any personal way. It will be interesting to see if he has a role in the coming story. Dickens seldom introduces even a minor character without purpose.

reply

|

flag

The rejection John Chivery experiences does indeed hurt him deeply and we see him cry and write his epitaph (would he consider suicide at this rejection?) As Sara mentioned, it may be that John will reappear later. I feel he will always deeply love Amy even after her rejection. Mention is made of John's simple-mindedness, but even the slow of mind have strong emotions and love is the strongest.

The rejection John Chivery experiences does indeed hurt him deeply and we see him cry and write his epitaph (would he consider suicide at this rejection?) As Sara mentioned, it may be that John will reappear later. I feel he will always deeply love Amy even after her rejection. Mention is made of John's simple-mindedness, but even the slow of mind have strong emotions and love is the strongest.

It dawns on me that this is the first time we have seen Amy do something that could be deemed "selfish", as in considering herself more than the other person. It is a very humanizing chapter for me, because she is almost too good and we see that she can (although she hates to) hurt someone else in preservation of her own feelings.

It dawns on me that this is the first time we have seen Amy do something that could be deemed "selfish", as in considering herself more than the other person. It is a very humanizing chapter for me, because she is almost too good and we see that she can (although she hates to) hurt someone else in preservation of her own feelings.

Good point, Amy's family would be happy for her to marry John but she doesn't capitulate.

Good point, Amy's family would be happy for her to marry John but she doesn't capitulate.John's imagining of tombstones reminds me of the current tendency to visualize headlines about oneself or others.

Interestingly, rather than being "selfish," I thought Amy, who knows well her own mind and heart, also knew that to encourage John in his pursuit of her would be cruel to him because she does not have mutual feelings toward him and a marriage would not work out between them - she does not love him. To marry him because his family approved or her father approved or because of John's idyllic perception of what their marriage would be would hurt him even more - she is concerned about him.

Interestingly, rather than being "selfish," I thought Amy, who knows well her own mind and heart, also knew that to encourage John in his pursuit of her would be cruel to him because she does not have mutual feelings toward him and a marriage would not work out between them - she does not love him. To marry him because his family approved or her father approved or because of John's idyllic perception of what their marriage would be would hurt him even more - she is concerned about him. She states, "when you think of me at all, John, let it only be as the child you have seen grow up in the prison... I am unprotected and solitary." She explains she knows him to be generous and trusts him not to ever search her out and visit (intrude) upon her solitude. Wishing he will have a good wife one day and be a happy man, she negates any hope he had of a marriage which could free her of some burdens in her life - to my view a kind thing rather than a selfish thing - and consistent with her behavior to care for others.

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Interestingly, rather than being "selfish," I thought Amy, who knows well her own mind and heart, also knew that to encourage John in his pursuit of her would be cruel to him because she does not h..."

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Interestingly, rather than being "selfish," I thought Amy, who knows well her own mind and heart, also knew that to encourage John in his pursuit of her would be cruel to him because she does not h..."I agree with you Elizabeth. I do not think she should marry him out of kindness. I believe that it was kinder for her to turn him down. Now perhaps he will find someone else. I also noticed that he does not have grand dreams of what he will do for her. On the imagined gravestone it says that she was born, lived and died in the Marshalsea. I hope that whatever happens, she will do better than that.

I put it in quotes because I did not mean selfish in that regard...I meant thinking of her own feelings, which she seldom seems to do. I realize she was kind and I don't think she should have accepted if she did not feel the same for him. She generally thinks so little of herself, however, that I found it refreshing that she was able to say to him, knowing it would hurt him, that she did not want his attentions. I could not think of another word to express what I was thinking, but I suppose "selfish" was not the right choice, since it denotes something negative which I did not intend.

I put it in quotes because I did not mean selfish in that regard...I meant thinking of her own feelings, which she seldom seems to do. I realize she was kind and I don't think she should have accepted if she did not feel the same for him. She generally thinks so little of herself, however, that I found it refreshing that she was able to say to him, knowing it would hurt him, that she did not want his attentions. I could not think of another word to express what I was thinking, but I suppose "selfish" was not the right choice, since it denotes something negative which I did not intend.

This was a sweet and sad chapter. I feel badly for John, and also for Amy for being put in that position. It was so painful for her to tell him to not speak of his feelings.

This was a sweet and sad chapter. I feel badly for John, and also for Amy for being put in that position. It was so painful for her to tell him to not speak of his feelings. I thought, too, that Amy may be developing feelings for Arthur since she frequently visits the Iron Bridge, where they first walked & talked.

Poor John!

It is interesting that John is the first one who refers to her as Amy, there’s no little Dorrit in his mind. I think Amy does the right, she doesn’t want to string him along like her family has been doing.

It is interesting that John is the first one who refers to her as Amy, there’s no little Dorrit in his mind. I think Amy does the right, she doesn’t want to string him along like her family has been doing.I think for me the saddest moment in the chapter was the first imagined tombstone saying that Amy was born, lived and died in the prison. Like Katy, I want so much more for her.

We’ve just read two chapters on a row of young love. Henry Gowan and Pet care for each other, but her parents object. And in this chapter, Young John cares for Amy. Henry comes for dinner every Sunday and John visits Amy’s father every Sunday.

We’ve just read two chapters on a row of young love. Henry Gowan and Pet care for each other, but her parents object. And in this chapter, Young John cares for Amy. Henry comes for dinner every Sunday and John visits Amy’s father every Sunday.

Another set of opposites! Nice observation, Kathleen!

Another set of opposites! Nice observation, Kathleen!Pet "loves" Henry and family (parents) disapprove of the relationship.

Amy doesn't love John and family approves of the "relationship".

As for the families' perspectives:

Pet's family care for her deeply and truly. They want what is best for HER.

Amy's family see her as a meal ticket or helper when in trouble. They want what is best for THEM. Do they care & love her as a person and for who she is? That hasn't been shown yet.

The Meagles have stated they travelled out of the country to separate Pet from Henry -- didn't work! Arthur notices the look of disfavor toward Henry on the faces of Mr. & Mrs. Meagles.

The Meagles have stated they travelled out of the country to separate Pet from Henry -- didn't work! Arthur notices the look of disfavor toward Henry on the faces of Mr. & Mrs. Meagles.

Great comments about John, everyone! I do feel sorry for John but also, like many of the people in Amy's life, he's only thinking of himself. He does genuinely love her but, in many ways, it's a selfish love as shown by the way he pictures himself and his dramatic gravestone.

Great comments about John, everyone! I do feel sorry for John but also, like many of the people in Amy's life, he's only thinking of himself. He does genuinely love her but, in many ways, it's a selfish love as shown by the way he pictures himself and his dramatic gravestone.

Sara wrote: "I put it in quotes because I did not mean selfish in that regard...I meant thinking of her own feelings, which she seldom seems to do. I realize she was kind and I don't think she should have accep..."

Sara wrote: "I put it in quotes because I did not mean selfish in that regard...I meant thinking of her own feelings, which she seldom seems to do. I realize she was kind and I don't think she should have accep..."Thanks for explaining Sara. I was kind of surprised that you thought she was selfish for turning him down, but now I understand what you meant.

Lovely sensitive observations, everyone. I do admit I find John a sad, almost tragic, character here. And the opposites in different families were pointed up nicely :)

And so we are now at the end of installment 5.

And so we are now at the end of installment 5.

message 166:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 03, 2020 06:39AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 19:

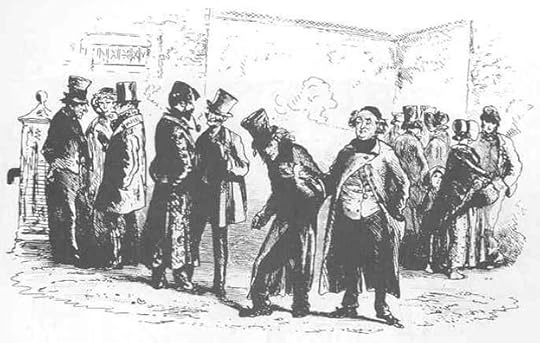

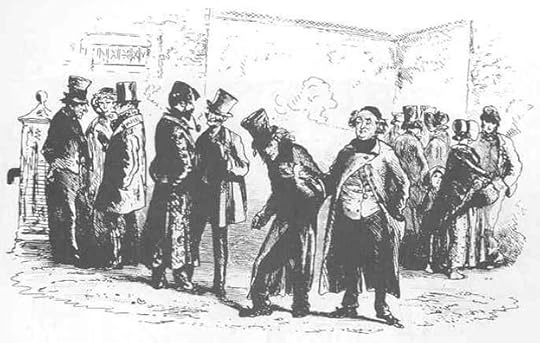

We begin the 6th installment back in the Marshalsea. The Father of the Marshalsea, Mr. William Dorrit, is walking up and down the College-yard with his brother Frederick. A distinction is made between the aristocratic or Pump side, and the Poor side. The Father of the Marshalsea is “courtly, condescending, and benevolently conscious of [his] position”, whereas Frederick, who is free to come and go as he pleases, is, curiously “humbled, bowed, withered, and faded”:

The Brothers - Phiz

The Father of the Marshalsea makes great play of being concerned for his unfortunate shabby brother, and comments that he seems “a little low this evening”. He suggests that Frederick might smarten himself up; observing with apparent sadness that he really does not take care of himself. The Father of the Marshalsea says that his brother should be more like him. He doubts whether Frederick’s habits are as precise and methodical as his own; he believes in a strict schedule and punctuality. William will “parade” in the yard, eat and read at certain times of the day, and receive his visitors at certain hours. He says these are important values, which he has also inculcated in his daughter Amy, and that she is a good girl because of this.

William’s show of beneficence towards his brother continues, as “with a shrug of modest self-depreciation” he graciously says that of course Frederick must go home if he is tired, and must not stay on his account.

The narrator sardonically comments that:

“Nothing would have been wanting to the perfection of his [William’s] character as a fraternal guide, philosopher and friend, if he had only steered his brother clear of ruin, instead of bringing it upon him.”

Mr. William Dorrit now stops to talk with the turnkey, Mr. Chivery, but this evening Mr. Chivery does not seem to be as respectful as usual. Mr. Dorrit says how smart John had been looking this evening, but Mr. Chivery seems sullen, and speaks in a “low growl”, which the benignant Father of the Marshalsea professes not to understand.

As he turns to go back to his room Mr. Dorrit honours the “collegians” who are still in the yard with a speech consisting of a stream of homilies, telling them the reasons why his brother, who is so infirm and feeble, would never be able to survive and live in the Marshalsea as he does.

Mr. Dorrit now returns to his chambers, where Amy has laid the table for his supper. He seems unusually downcast:

“An uneasiness stole over him that was like a touch of shame”

and confides in Amy that Mr. Chivery is not as obliging and attentive tonight as he usually is. Mr. Chivery, he says, was actually quite short with him, which is worrying. If he loses his status with the prison officers, he says, he would starve to death. He goes on to recollect a turnkey he once knew, whose young brother admired the daughter of one of the collegians, and asked Mr. Dorrit’s advice on the matter.

Mr. Dorrit does not finish the story. Although he pretends it is merely rambling thoughts, it is a clear parallel to Amy’s situation, which she cannot bear to talk about, whether it was deliberate or not. Amy puts her hands on her father’s lips to stop him talking, then puts her arm around his neck and her head on his shoulder for a while.

Eventually Mr. Dorrit begins his meal, but is clearly out of sorts, and working himself up to feel desperately sorry for himself:

“What does it matter whether I eat or starve? What does it matter whether such a blighted life as mine comes to an end, now, next week, or next year? What am I worth to anyone? A poor prisoner, fed on alms and broken victuals; a squalid, disgraced wretch!”

Her father tells her that he wishes Amy had been able to see him as her mother had. He had been young, independent, good-looking and accomplished. People had envied him. He is mortified that his children will never see the man he had been, and can never be proud of him:

“O despise me, despise me! … even you, Amy! … I have sunk too low to care long even for that.”

“Miserably whining … he burst into tears of maudlin pity for himself” and says at least he maintains some respect at the Marshalsea, where he is the chief person of the place and not quite so trodden down.

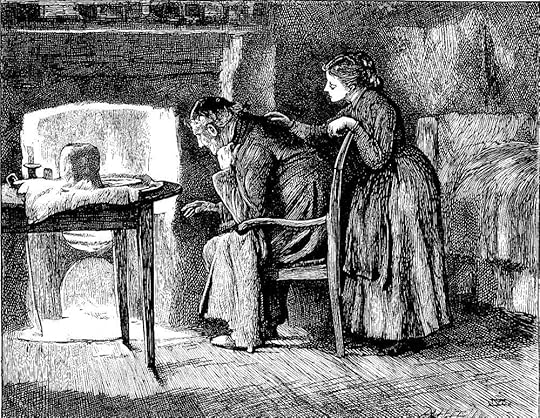

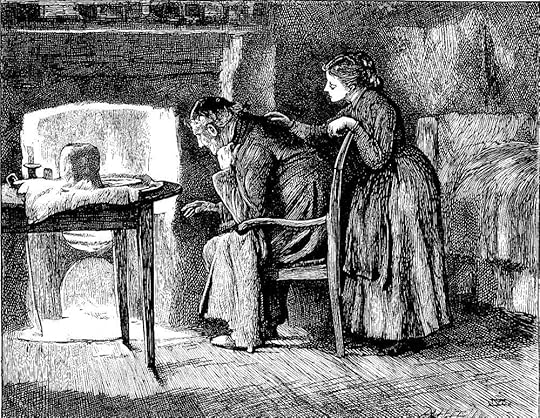

Little Dorrit and her father - James Mahoney

Amy soothes him and comforts him, however long it takes; she is “a fountain of love and fidelity”. Eventually Mr. Dorrit is his old self again, composed and magnanimous, ready to give advice:

“like a great moral Lord Chesterfield, or Master of the ethical ceremonies of the Marshalsea.”

Amy says she will sit with her father until the morning, to which of course he graciously agrees, for her benefit, he says, if she feels solitary. But the narrator observes:

“All this time he had never once thought of her dress, her shoes, her need of anything. No other person upon earth, save herself, could have been so unmindful of her wants.”

and even so, her father has one last word:

“You know my position, Amy. I have not been able to do much for you; but all I have been able to do, I have done.”

At daybreak Amy creeps back to her room, compassionate and sorrowful about her “dear, long-suffering, unfortunate, much-changed, dear dear father”, convinced that she has never seen him as he truly should be: “prosperous and happy”.

We begin the 6th installment back in the Marshalsea. The Father of the Marshalsea, Mr. William Dorrit, is walking up and down the College-yard with his brother Frederick. A distinction is made between the aristocratic or Pump side, and the Poor side. The Father of the Marshalsea is “courtly, condescending, and benevolently conscious of [his] position”, whereas Frederick, who is free to come and go as he pleases, is, curiously “humbled, bowed, withered, and faded”:

The Brothers - Phiz

The Father of the Marshalsea makes great play of being concerned for his unfortunate shabby brother, and comments that he seems “a little low this evening”. He suggests that Frederick might smarten himself up; observing with apparent sadness that he really does not take care of himself. The Father of the Marshalsea says that his brother should be more like him. He doubts whether Frederick’s habits are as precise and methodical as his own; he believes in a strict schedule and punctuality. William will “parade” in the yard, eat and read at certain times of the day, and receive his visitors at certain hours. He says these are important values, which he has also inculcated in his daughter Amy, and that she is a good girl because of this.

William’s show of beneficence towards his brother continues, as “with a shrug of modest self-depreciation” he graciously says that of course Frederick must go home if he is tired, and must not stay on his account.

The narrator sardonically comments that:

“Nothing would have been wanting to the perfection of his [William’s] character as a fraternal guide, philosopher and friend, if he had only steered his brother clear of ruin, instead of bringing it upon him.”

Mr. William Dorrit now stops to talk with the turnkey, Mr. Chivery, but this evening Mr. Chivery does not seem to be as respectful as usual. Mr. Dorrit says how smart John had been looking this evening, but Mr. Chivery seems sullen, and speaks in a “low growl”, which the benignant Father of the Marshalsea professes not to understand.

As he turns to go back to his room Mr. Dorrit honours the “collegians” who are still in the yard with a speech consisting of a stream of homilies, telling them the reasons why his brother, who is so infirm and feeble, would never be able to survive and live in the Marshalsea as he does.

Mr. Dorrit now returns to his chambers, where Amy has laid the table for his supper. He seems unusually downcast:

“An uneasiness stole over him that was like a touch of shame”

and confides in Amy that Mr. Chivery is not as obliging and attentive tonight as he usually is. Mr. Chivery, he says, was actually quite short with him, which is worrying. If he loses his status with the prison officers, he says, he would starve to death. He goes on to recollect a turnkey he once knew, whose young brother admired the daughter of one of the collegians, and asked Mr. Dorrit’s advice on the matter.

Mr. Dorrit does not finish the story. Although he pretends it is merely rambling thoughts, it is a clear parallel to Amy’s situation, which she cannot bear to talk about, whether it was deliberate or not. Amy puts her hands on her father’s lips to stop him talking, then puts her arm around his neck and her head on his shoulder for a while.

Eventually Mr. Dorrit begins his meal, but is clearly out of sorts, and working himself up to feel desperately sorry for himself:

“What does it matter whether I eat or starve? What does it matter whether such a blighted life as mine comes to an end, now, next week, or next year? What am I worth to anyone? A poor prisoner, fed on alms and broken victuals; a squalid, disgraced wretch!”

Her father tells her that he wishes Amy had been able to see him as her mother had. He had been young, independent, good-looking and accomplished. People had envied him. He is mortified that his children will never see the man he had been, and can never be proud of him:

“O despise me, despise me! … even you, Amy! … I have sunk too low to care long even for that.”

“Miserably whining … he burst into tears of maudlin pity for himself” and says at least he maintains some respect at the Marshalsea, where he is the chief person of the place and not quite so trodden down.

Little Dorrit and her father - James Mahoney

Amy soothes him and comforts him, however long it takes; she is “a fountain of love and fidelity”. Eventually Mr. Dorrit is his old self again, composed and magnanimous, ready to give advice:

“like a great moral Lord Chesterfield, or Master of the ethical ceremonies of the Marshalsea.”

Amy says she will sit with her father until the morning, to which of course he graciously agrees, for her benefit, he says, if she feels solitary. But the narrator observes:

“All this time he had never once thought of her dress, her shoes, her need of anything. No other person upon earth, save herself, could have been so unmindful of her wants.”

and even so, her father has one last word:

“You know my position, Amy. I have not been able to do much for you; but all I have been able to do, I have done.”

At daybreak Amy creeps back to her room, compassionate and sorrowful about her “dear, long-suffering, unfortunate, much-changed, dear dear father”, convinced that she has never seen him as he truly should be: “prosperous and happy”.

message 167:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 03, 2020 06:44AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What a character William Dorrit is! Totally absorbed in his own self-aggrandisement and the role he plays as Father of the Marshalsea, he seems to view the “tributes” as only natural and right to someone in his position. He is oblivious to how his children spend their time, and to all the sacrifices Amy makes for him. "All I have been able to do, I have done” I wonder what this is - we were told that Amy was raised mainly by the turnkey! Plus, denying the fact that he was the cause of his brother’s downfall, he now looks for approval from those around him, that he is so solicitous of such an enfeebled wretch.

Yet Amy seems to have compassion for her father, realising that this is the only way he has been able to cope with his 22 years of incarceration, with no real hope of ever being at liberty.

Or … there is another interpretation. William Dorrit could indeed be a master of self-deception, or he could simply be a scheming, self-serving, self-justifying hypocrite. I would like to believe Amy’s compassionate interpretation, but plenty of readers view him merely as a selfish and manipulative father (and brother) with pretensions to gentility; one of Dickens’s many unpleasant hypocrites. It will be interesting to get more views on this :)

Yet Amy seems to have compassion for her father, realising that this is the only way he has been able to cope with his 22 years of incarceration, with no real hope of ever being at liberty.

Or … there is another interpretation. William Dorrit could indeed be a master of self-deception, or he could simply be a scheming, self-serving, self-justifying hypocrite. I would like to believe Amy’s compassionate interpretation, but plenty of readers view him merely as a selfish and manipulative father (and brother) with pretensions to gentility; one of Dickens’s many unpleasant hypocrites. It will be interesting to get more views on this :)

message 168:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 03, 2020 06:34AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more …

About Lord Chesterfield.

The narrator refers to Mr. Dorrit as “like a great moral Lord Chesterfield, or Master of the ethical ceremonies of the Marshalsea”. It’s where Amy is comforting her father, near the end of the chapter. It reminded me that Charles Dickens created a most unlikable, deviously smooth character in Barnaby Rudge. He was called "Mr. Chester", and was based on a real person, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield. Charles Dickens obviously hated this man, to keep portraying him this way in his novels! So here’s a bit about the actual Lord Chesterfield.

Philip Dormer Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield, (1694-1773) was a statesman, diplomat, and man of letters. He was also an acclaimed wit, with what some thought “winning manners”. Lord Chesterfield was famous for a book of etiquette, called Lord Chesterfield, Letters Written To His Natural Son On Manners And Morals, in which he epitomised the restraint of polite 18th-century society. Philip Dormer Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield’s wit and urbanity were praised by many of his leading contemporaries, and he was on familiar terms with Alexander Pope, John Gay, and Voltaire. He was the patron of many struggling authors, including Samuel Johnson (yes, that one!).

Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield

In 1755 he and Samuel Johnson had a dispute over “A Dictionary of the English Language”. Eight years earlier, in 1747, Samuel Johnson had sent Lord Chesterfield, (who was at that time then the Secretary of State) an outline of his Dictionary, along with a business offer. Lord Chesterfield agreed and invested £10 pounds. He also wrote 2 articles praising Samuel Johnson. However, Samuel Johnson was disappointed at Chesterfield’s lack of interest in the project whole it was ongoing. He retaliated by condemning him in a now-famous “Letter to Chesterfield” (1755) which was an attack on patrons. Samuel Johnson) to be selfish, calculating and contemptuous. Those against him said that despite his talents, he was not naturally generous, and he practised dissimulation until it became part of his nature.

Here is an extract from Lord Chesterfield’s “Letters Written To His Natural Son On Manners And Morals”:

“I would heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile, but never heard to laugh while you live. Frequent and loud laughter is the characteristic of folly and ill-manners; it is the manner in which the mob express their silly joy at silly things; and they call it being merry. In my mind there is nothing so illiberal, and so ill-bred, as audible laughter. I am neither of a melancholy nor a cynical disposition, and am as willing and as apt to be pleased as anybody; but I am sure that since I have had the full use of my reason nobody has ever heard me laugh.”

“Take the tone of the company that you are in, and do not pretend to give it; be serious, gay, or even trifling, as you find the present humor of the company; this is an attention due from every individual to the majority. Do not tell stories in company; there is nothing more tedious and disagreeable; if by chance you know a very short story, and exceedingly applicable to the present subject of conversation, tell it in as few words as possible; and even then, throw out that you do not love to tell stories; but that the shortness of it tempted you.”

“Never maintain an argument with heat and clamour, though you think or know yourself to be in the right: but give your opinion modestly and coolly, which is the only way to convince; and, if that does not do, try to change the conversation, by saying, with good humour, “We shall hardly convince one another, nor is it necessary that we should, so let us talk of something else.”

I wonder if this Mr. Dorrit emulates these manners. Charles Dickens certainly seems to be pointing us that way!

About Lord Chesterfield.

The narrator refers to Mr. Dorrit as “like a great moral Lord Chesterfield, or Master of the ethical ceremonies of the Marshalsea”. It’s where Amy is comforting her father, near the end of the chapter. It reminded me that Charles Dickens created a most unlikable, deviously smooth character in Barnaby Rudge. He was called "Mr. Chester", and was based on a real person, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield. Charles Dickens obviously hated this man, to keep portraying him this way in his novels! So here’s a bit about the actual Lord Chesterfield.

Philip Dormer Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield, (1694-1773) was a statesman, diplomat, and man of letters. He was also an acclaimed wit, with what some thought “winning manners”. Lord Chesterfield was famous for a book of etiquette, called Lord Chesterfield, Letters Written To His Natural Son On Manners And Morals, in which he epitomised the restraint of polite 18th-century society. Philip Dormer Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield’s wit and urbanity were praised by many of his leading contemporaries, and he was on familiar terms with Alexander Pope, John Gay, and Voltaire. He was the patron of many struggling authors, including Samuel Johnson (yes, that one!).

Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield

In 1755 he and Samuel Johnson had a dispute over “A Dictionary of the English Language”. Eight years earlier, in 1747, Samuel Johnson had sent Lord Chesterfield, (who was at that time then the Secretary of State) an outline of his Dictionary, along with a business offer. Lord Chesterfield agreed and invested £10 pounds. He also wrote 2 articles praising Samuel Johnson. However, Samuel Johnson was disappointed at Chesterfield’s lack of interest in the project whole it was ongoing. He retaliated by condemning him in a now-famous “Letter to Chesterfield” (1755) which was an attack on patrons. Samuel Johnson) to be selfish, calculating and contemptuous. Those against him said that despite his talents, he was not naturally generous, and he practised dissimulation until it became part of his nature.

Here is an extract from Lord Chesterfield’s “Letters Written To His Natural Son On Manners And Morals”:

“I would heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile, but never heard to laugh while you live. Frequent and loud laughter is the characteristic of folly and ill-manners; it is the manner in which the mob express their silly joy at silly things; and they call it being merry. In my mind there is nothing so illiberal, and so ill-bred, as audible laughter. I am neither of a melancholy nor a cynical disposition, and am as willing and as apt to be pleased as anybody; but I am sure that since I have had the full use of my reason nobody has ever heard me laugh.”

“Take the tone of the company that you are in, and do not pretend to give it; be serious, gay, or even trifling, as you find the present humor of the company; this is an attention due from every individual to the majority. Do not tell stories in company; there is nothing more tedious and disagreeable; if by chance you know a very short story, and exceedingly applicable to the present subject of conversation, tell it in as few words as possible; and even then, throw out that you do not love to tell stories; but that the shortness of it tempted you.”

“Never maintain an argument with heat and clamour, though you think or know yourself to be in the right: but give your opinion modestly and coolly, which is the only way to convince; and, if that does not do, try to change the conversation, by saying, with good humour, “We shall hardly convince one another, nor is it necessary that we should, so let us talk of something else.”

I wonder if this Mr. Dorrit emulates these manners. Charles Dickens certainly seems to be pointing us that way!

Sara wrote: "It dawns on me that this is the first time we have seen Amy do something that could be deemed "selfish", as in considering herself more than the other person.

Sara wrote: "It dawns on me that this is the first time we have seen Amy do something that could be deemed "selfish", as in considering herself more than the other person. Sara, In reconsidering chapter 18, I think you hit the nail on the head that Amy is doing something solely for herself when she goes to the Bridge (a place of fond memories of walks with Arthur) escaping to a place that distracts her from her burdens and provides solace and comfort to her. Dickens' focus on John's actions and desires makes it easy for the reader to overlook at first what Amy is doing and apparently has been doing to contemplate and perhaps dream of a better life for herself. This solitude gives her some peace of mind away from concerns of the prison and her oblivious, selfish family. She is totally distracted from the cares of her world for the moment and perhaps contemplating about a different life with Arthur. John intrudes upon this private moment and she bemoans that her father unwittingly and inadvertently (selfishly) has revealed her "secret" place of solitude. She is so adamant about securing these private moments of solitude that she tells John to never come to there and speak with her again. It is easy to forget that selfless Amy desires time for self in private.

Her behavior reminds me when someone is reading a good book like Little Dorrit to escape real life for a while and there is constant interruption - LOL!

I can't imagine Mr. Dorrit would do anything for Amy or anyone else, except making himself comfortable.

I can't imagine Mr. Dorrit would do anything for Amy or anyone else, except making himself comfortable. I have impressed upon Amy during many years, that I must have my meals (for instance) punctually. Amy has grown up in a sense of the importance of these arrangements, and you know what a good girl she is.'

Mr. Dorrit's all comments makes Amy more pitiful for me.

He aware of himself and everything but prefer to ignore it. He really different kind of villain.

To answer your question, Jean, while reading this chapter I kept thinking that this chapter should be called The Hypocrisy of William Dorrit. We have examples throughout, particularly towards his brother and towards Amy. The worst is his, ahem, attempting to pimp out Amy to Chivery's son and then after a pity party for himself he then moves on to ask Amy to make him this and that item of clothing and to buy him a new cravat! As Dickens writes afterwards, when has Amy ever had any new clothing, etc..? His selfishness and hypocrisy was on full display in this chapter as well as Amy's denial of same in her father. I can feel some compassion for the man given his circumstances, but my true compassion goes out to Amy, especially in the final paragraph which was very moving.

To answer your question, Jean, while reading this chapter I kept thinking that this chapter should be called The Hypocrisy of William Dorrit. We have examples throughout, particularly towards his brother and towards Amy. The worst is his, ahem, attempting to pimp out Amy to Chivery's son and then after a pity party for himself he then moves on to ask Amy to make him this and that item of clothing and to buy him a new cravat! As Dickens writes afterwards, when has Amy ever had any new clothing, etc..? His selfishness and hypocrisy was on full display in this chapter as well as Amy's denial of same in her father. I can feel some compassion for the man given his circumstances, but my true compassion goes out to Amy, especially in the final paragraph which was very moving.

I agree with the above comments.

I agree with the above comments. This chapter shows us that William's actions and manipulations are deliberate and thought out; they aren't a weak personality but a cunning, manipulative one.

I was struck by Nisa's quote, too, while reading. It shows that Amy was molded into being William's servant and provider.

We only have hints that the Dorritts were a family of some wealth and standing. This implies having servants and being taken care of. Perhaps William was always spoiled, pampered and never had to do for himself? He then found a way to continue this in his new conditions.

Whatever the background, he's using his daughter and not seeing her as a person and individual.

Petra said, "Whatever the background, he's using his daughter and not seeing her as a person and individual. "

Petra said, "Whatever the background, he's using his daughter and not seeing her as a person and individual. "I completely agree. Amy is not a person in her own right but only someone to serve him and his needs. It would be interesting to see how he would behave if she did not put all of his needs above her own.

I agree that William Dorrit is not a good father ans is very selfish though I wonder if he could be different if his family treated him differently, I know they are trying not to upset him by not telling them what goes on in his own family maybe if he was treated as an adult, he might grow up a little? He has created the set up where he is treated as a child, but people could refuse to conform to it and that could be good for William.

I agree that William Dorrit is not a good father ans is very selfish though I wonder if he could be different if his family treated him differently, I know they are trying not to upset him by not telling them what goes on in his own family maybe if he was treated as an adult, he might grow up a little? He has created the set up where he is treated as a child, but people could refuse to conform to it and that could be good for William.

Amy taking care of her father reminds me of Agnes taking care of her father in David Copperfield. Perhaps, girls were expected to do that back then.

Amy taking care of her father reminds me of Agnes taking care of her father in David Copperfield. Perhaps, girls were expected to do that back then. On the other hand, Mr. Dorrit does seem to be a sort of villian, as Nisa pointed out (and is how I feel). Where as, Agnes's father did not seem bad at all.

I wonder if Amy feels that she cannot even think of marriage because she must take care of her father.

Mr. Dorrit is selfish--and I mean that in the negative connotation of the word! He never gives a moment's thought for Amy and she gives so little thought to anything other than him. I find I have no sympathy for him at all, even if he is imprisoned unjustly, because he visits his on bad fortune upon the very ones he should be trying to protect from it. I think Amy is a good daughter and a loving person despite his being her father, certainly not because of it.

Mr. Dorrit is selfish--and I mean that in the negative connotation of the word! He never gives a moment's thought for Amy and she gives so little thought to anything other than him. I find I have no sympathy for him at all, even if he is imprisoned unjustly, because he visits his on bad fortune upon the very ones he should be trying to protect from it. I think Amy is a good daughter and a loving person despite his being her father, certainly not because of it.BTW, I enjoyed the information on Lord Chesterfield, Jean. I would hate to have run afoul of Dickens. You would show up in his next novel as a vile sort of person indeed.

Debra wrote: "Amy taking care of her father reminds me of Agnes taking care of her father in David Copperfield. Perhaps, girls were expected to do that back then.

Debra wrote: "Amy taking care of her father reminds me of Agnes taking care of her father in David Copperfield. Perhaps, girls were expected to do that back then. On the other hand, Mr. Dorrit does seem to be ..."

Debra, I wonder if you are right that Amy feels she cannot marry because she must take care of her father.

Once again, I am writing my comments while the chapter is still fresh in my mind and before I read what others say, so forgive me if I repeat the sentiments of other group members.

I found this chapter disturbing, and not in a good way. Dickens clearly shows us that Amy’s father is vain, manipulative, self-pitying, and selfish. Mr. Dorrit really goes on (albeit indirectly) about how Amy’s rejection of John has affected his interaction with the turnkey, John’s father. It’s clear that he knows about John and is trying to guilt trip Amy into accepting John’s love and his unstated marriage proposal.

While Amy’s devotion to her dad is sweet and noble, I had some difficulty with Dickens’ obvious idea that her totally self effacing invisibility was the peak of womanly virtue. She was expected to be a nobody without any needs, and her father, although he does love her, is exploiting this. This struck too close to home for me. Unlike Amy, I angered some people in my life by refusing to be the doormat/scapegoat they required me to be (Amy at least is not being scapegoated). I get that the Victorian ideal for female behavior was different than it is now, but this still bothers me..

Amy’s request that Clennam not give “tributes” to her father and her upset with her father for revealing to John her favorite spot on the Iron Bridge do show that she may not be as blind to her father’s faults as she appears.

There was still some poignant Dickensian charm in this chapter, as the following quote shows:

“the homily with which he improved and pointed the occasion to the company in the Lodge before turning into the sallow yard again, and going with his own poor shabby dignity past the Collegian in the dressing-gown who had no coat, and past the Collegian in the sea-side slippers who had no shoes, and past the stout greengrocer Collegian in the corduroy knee-breeches who had no cares, and past the lean clerk Collegian in buttonless black who had no hopes, up his own poor shabby staircase to his own poor shabby room.”

Mona, wrote "I had some difficulty with Dickens’ obvious idea that her totally self effacing invisibility was the peak of womanly virtue. She was expected to be a nobody without any needs, and her father, although he does love her, is exploiting this. "

Mona, wrote "I had some difficulty with Dickens’ obvious idea that her totally self effacing invisibility was the peak of womanly virtue. She was expected to be a nobody without any needs, and her father, although he does love her, is exploiting this. "Mona, since Dickens was very critical of many of the norms in his Victorian world I do not think that his writing about Amy as self-sacrificing, etc. means that he agrees with his society's norms; in fact, I think he was critical of the position of women in his society. Remember the suicidal woman who was headed for the river? I don't think he wrote abut her because he approved of women killing themselves because they ran out of options. So far, I think he's just showing how things were. We are still at the beginning of the story and I am hopeful that Amy's lot will change.

message 180:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 05, 2020 01:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Anne wrote: "We are still at the beginning of the story and I am hopeful that Amy's lot will change ..."

Yes, since she is a title character we have to expect at least some development there! And like Anne, I do not really believe the narrator has expressed approval of "her totally self effacing invisibility", as you put it Mona. In this chapter, and the previous one, (as has been picked up), Amy is actually standing strong for what she wants, both with John and with her father. She just does this in a quiet way, rather than flouncing around like her sister Fanny! She will deny herself comfort, eg. staying overnight because her father needs her; as we have seen, this kindness is part of her character. Yes, we have seen she is exploited by all her family (except Frederick), but when she wants to, she can stand firm. I do think this is a case of having your radar up for something, (as we all do) and sadly, we can be a bit over-sensitive to something if we come across something in a novel which hits close to home :( Some novels I can hardly bear to read, eg. Mary Barton by Elizabeth Gaskell, as they are so close to my family's origins, but they do not affect others in that way.

The suicidal woman headed for the river who Anne refers to, was indeed based on reality. Charles Dickens described another, Martha Endel, whom we read about in David Copperfield. She was based on a real person he had tried to help in his "home for fallen women" Urania Cottage. He includes these observation from life, to make his points about society's ills.

So with Amy, it is likely that this is a description of someone who is as disadvantaged as it is possible to be, but still, by her tenacity, intelligence and quiet strength, achieves things for both her family, and a quiet space to think, for herself.

"Amy’s request that Clennam not give “tributes” to her father and her upset with her father for revealing to John her favorite spot on the Iron Bridge do show that she may not be as blind to her father’s faults as she appears."

Yes, absolutely! I like this :)

Yes, since she is a title character we have to expect at least some development there! And like Anne, I do not really believe the narrator has expressed approval of "her totally self effacing invisibility", as you put it Mona. In this chapter, and the previous one, (as has been picked up), Amy is actually standing strong for what she wants, both with John and with her father. She just does this in a quiet way, rather than flouncing around like her sister Fanny! She will deny herself comfort, eg. staying overnight because her father needs her; as we have seen, this kindness is part of her character. Yes, we have seen she is exploited by all her family (except Frederick), but when she wants to, she can stand firm. I do think this is a case of having your radar up for something, (as we all do) and sadly, we can be a bit over-sensitive to something if we come across something in a novel which hits close to home :( Some novels I can hardly bear to read, eg. Mary Barton by Elizabeth Gaskell, as they are so close to my family's origins, but they do not affect others in that way.

The suicidal woman headed for the river who Anne refers to, was indeed based on reality. Charles Dickens described another, Martha Endel, whom we read about in David Copperfield. She was based on a real person he had tried to help in his "home for fallen women" Urania Cottage. He includes these observation from life, to make his points about society's ills.

So with Amy, it is likely that this is a description of someone who is as disadvantaged as it is possible to be, but still, by her tenacity, intelligence and quiet strength, achieves things for both her family, and a quiet space to think, for herself.

"Amy’s request that Clennam not give “tributes” to her father and her upset with her father for revealing to John her favorite spot on the Iron Bridge do show that she may not be as blind to her father’s faults as she appears."

Yes, absolutely! I like this :)

message 181:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 05, 2020 01:14AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I do like everyone's thoughts about Amy, and everyone's indignation about William Dorrit :D I always find it difficult to get on Amy's wavelength with regard to him. Yes, she loves him, and can see him with clear eyes, i.e. why he has become as he is. But as France Andree said, it is interesting that nobody in his family challenges this behaviour. We have to assume that they see the benefits of being hypocritically self serving, and enjoy their falsely elevated position in the prison. Amy, however shows signs of firmness, in her not wanting to divulge her secret haunt, the Iron Bridge. It is indeed very important to her, as you said Robin, a rare private and quiet place.

Yes indeed Sara, Charles Dickens did have his knife into Lord Chesterfield! And from this we can understand that he is painting Mr. Dorrit as a smooth-talking hypocrite. As Nisa said, "He really is a different kind of villain".

In which case, we now also see that the only time he breaks down and is honest (although he is then such a whining drip) is in front of Amy. He recognises that she is straightforward and honest, and goes to her for comfort, even though she is his youngest child.

I could highlight so many more of these great comments, but it is late here, so am going offline.

In which case, we now also see that the only time he breaks down and is honest (although he is then such a whining drip) is in front of Amy. He recognises that she is straightforward and honest, and goes to her for comfort, even though she is his youngest child.

I could highlight so many more of these great comments, but it is late here, so am going offline.

The most disturbing comment from William Dorrit to Amy, for me, was him saying he woukd starve if he lost the favor of the turnkey. The turnkey gives him nothing. He woukd starve without Amy, and it seams he does not care enough to even recognize that.

The most disturbing comment from William Dorrit to Amy, for me, was him saying he woukd starve if he lost the favor of the turnkey. The turnkey gives him nothing. He woukd starve without Amy, and it seams he does not care enough to even recognize that.

We'll just have to wait and see, Katy and Jenny. I think we all feel a bit indignant about blinkered Mr. Dorrit!

But today's chapter, long though it is, is a real treat :)

But today's chapter, long though it is, is a real treat :)

message 186:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 04, 2020 02:14AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 20:

We are given a clue about this chapter in the first sentence, where the narrator comments that if Young John were a different sort of person, he could have written “a satire on family pride” about the Dorrits. And that is precisely what the author does here.

Tip, now at liberty, is not in the last interested in who paid his debts, but has got himself a promising job as a billiard-marker. He often visits the Marshalsea, and one thing slightly in his favour is that he “respected and admired his sister Amy” although “distinctly perceiving that she sacrificed her life to her father, and having no idea that she had done anything for himself”.

Tip and Fanny have learned well their father’s way of exaggerating their false connections to gentility; a “family skeleton”, to use whenever it is to their advantage:

“the more reduced and necessitous they were, the more pompously the skeleton emerged from its tomb; and that when there was anything particularly shabby in the wind, the skeleton always came out with the ghastliest flourish.”

Little Dorrit is on her way to see her sister Fanny, but when she gets to Mr. Cripples’s, she discovers that both her sister and her uncle have gone to the theatre where they work. The author paints a wonderfully atmospheric picture of the theatre for us, from the point of view of Amy: someone who has never seen the like, or had any information about it:

“Little Dorrit was almost as ignorant of the ways of theatres as of the ways of gold mines, and when she was directed to a furtive sort of door, with a curious up-all-night air about it, that appeared to be ashamed of itself and to be hiding in an alley, she hesitated to approach it.”

However she is encouraged by the fact that those around look quite similar to the inmates of the Marshalsea, who:

“made way for her to enter a dark hall—it was more like a great grim lamp gone out than anything else—where she could hear the distant playing of music and the sound of dancing feet. A man so much in want of airing that he had a blue mould upon him, sat watching this dark place from a hole in a corner, like a spider; and he told her that he would send a message up to Miss Dorrit”

Nearing her destination, accompanied by a woman who looks as though she needs ironing, Amy finds:

“a maze of dust, where a quantity of people were tumbling over one another, and where there was such a confusion of unaccountable shapes of beams, bulkheads, brick walls, ropes, and rollers, and such a mixing of gaslight and daylight, that they seemed to have got on the wrong side of the pattern of the universe.”

Fanny is most surprised to see her, “among the professionals” and goes on to say that quiet little thing though she is, Amy can find her way to any place. Fanny says that she would have never been able to do it, even though she knows so much more of the world. The narrator explains that:

“It was the family custom to lay it down as family law, that she was a plain domestic little creature, without the great and sage experience of the rest. This family fiction was the family assertion of itself against her services. Not to make too much of them.”

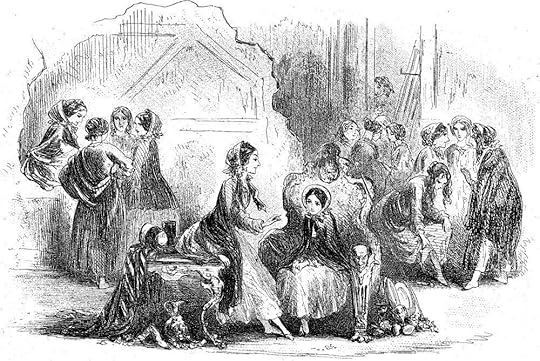

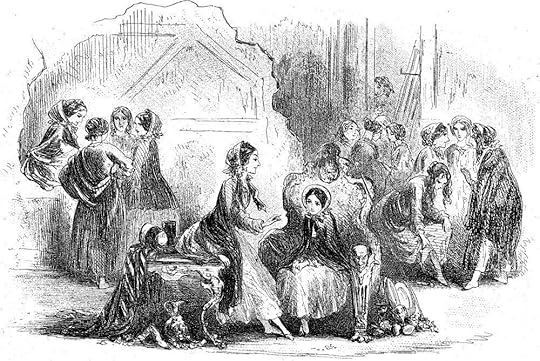

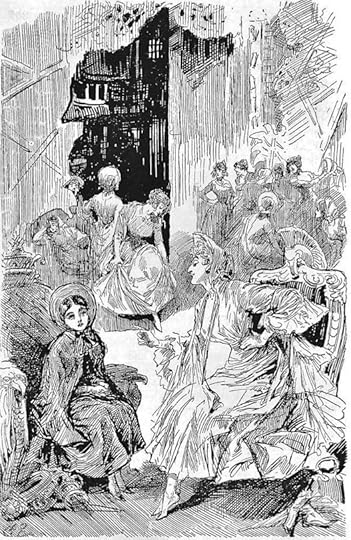

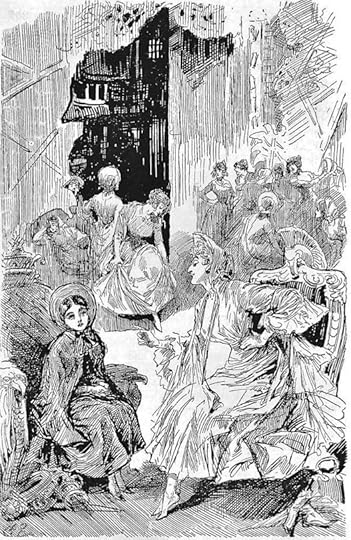

Fanny and Amy Dorrit backstage - Phiz

Amy tells her sister she has come because she wants to know more about the lady who gave Fanny a bracelet; she has not been quite easy since Fanny told her. There are various interruptions by theatrical callers, as Fanny is called to a dance rehearsal, but finally she is released along with all the other dancing girls (who too look as if they need ironing).

“something was rolled up or by other means got out of the way, and there was a great empty well before them, looking down into the depths of which Fanny said, ‘Now, uncle!’”

Frederick Dorrit feels most at home in the orchestra pit. All sorts of rumours are told about him, and the narrator tells us that it is quite a joke to the other members of the company, that this “pale phantom of a gentleman” lurks there with his clarionet, barely conscious of whatever else is going on outside himself:

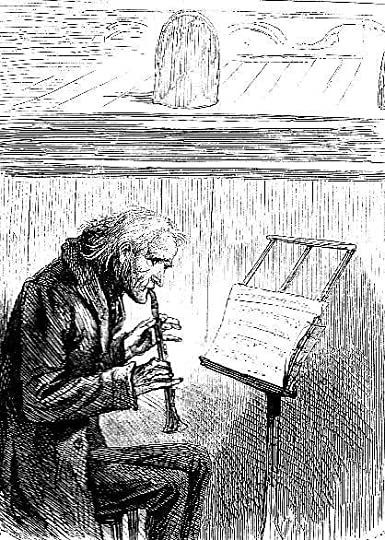

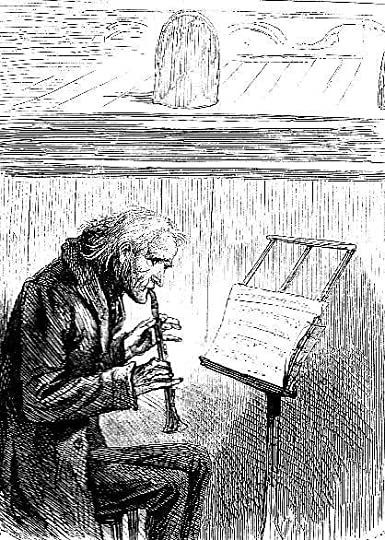

Frederick Dorrit andhis clarionet - Sol Etynge Jnr. - 1871

Fanny has to call for him three or four times before he knows they are there, but they eventually set off.

Fanny:

“was pretty, and conscious, and rather flaunting; and the condescension with which she put aside the superiority of her charms, and of her worldly experience, and addressed her sister on almost equal terms, had a vast deal of the family in it.”

They walk on to a cook’s shop, where Frederick will have his dinner:

“a dirty shop window in a dirty street, which was made almost opaque by the steam of hot meats, vegetables, and pudding”

but which sells substantial hot meals. Fanny gives their uncle a shilling, and he disappears inside.

Fanny suggests they walk to Harley Street, Cavendish Square, (a most distinguished address, as the narrator points out). Since, she says, Amy is curious about her, she is taking her sister to meet Mrs. Merdle, the lady who gave her the bracelet, and who lives in the grandest house on the street.

When Fanny knocks on the door, it is opened by a heavily powdered footman, backed up by two more footmen with powder on their heads. The sisters are shown into:

“a spacious semicircular drawing-room, one of several drawing-rooms, where there was a parrot on the outside of a golden cage holding on by its beak, with its scaly legs in the air, and putting itself into many strange upside-down postures. This peculiarity has been observed in birds of quite another feather, climbing upon golden wires.”

This heavy clue tells us that the parrot is a character in its own right, and indeed during the whole of the following discourse, it is the parrot who seems to be the most honest and frank of all those present.

To Little Dorrit’s eyes, this room is far more splendid than any room she has ever imagined. Mrs. Merdle enters the room:

“The lady was not young and fresh from the hand of Nature, but was young and fresh from the hand of her maid. She had large unfeeling handsome eyes, and dark unfeeling handsome hair, and a broad unfeeling handsome bosom, and was made the most of in every particular.”

Fanny introduces her sister to Mrs. Merdle, and asks Mrs. Merdle to tell Amy how they happen to know each other. Mrs. Merdle hesitates, because of Little Dorrit’s age, but Fanny says that she is much older than she looks. We then get one of Mrs. Merdle’s many pronouncements on the sad mores and restrictions of “Society”, whereupon:

“The parrot had given a most piercing shriek, as if its name were Society and it asserted its right to its exactions.”

Mrs. Merdle continues:

“We know it is hollow and conventional and worldly and very shocking, but unless we are Savages in the Tropical seas (I should have been charmed to be one myself—most delightful life and perfect climate, I am told), we must consult it.”

and the parrot also continues to give its opinion on the worth of what Mrs. Merdle is saying.

We learn the story which Fanny wishes Amy to hear, with apposite interjections from the parrot, as to the accuracy of Mrs. Merdle’s posturing and reasons.

Mrs. Merdle says that her husband is very wealthy and his influence is very great. She also has a twenty-three year old son, who is gay, very impressionable, and fascinated by the stage. Because of this he became fascinated by Fanny, and when his mother heard of this she assumed Fanny was a dancer at the opera. When she had learned the truth, and that (as she put it) Fanny had, by refusing his advances, tempted him into wanting to marry her, she became most distressed. His mother said that the anguish she suffered was so acute that she went to visit Fanny for herself.

She recounts that Fanny had countered her objections, saying that her own family’s standing in the society in which her father moves, is as good, if not superior, to the Merdles’. Moreover it is acknowledged by everyone. (Of course she does not say where this “society” actually is.) Her own brother, Fanny says, “would not consider such a connection any honour.”

Mrs. Merdle says that she had been so delighted that they could discuss the subject frankly, that she had immediately taken a bracelet from her arm, and given it to Fanny as a mark of her appreciation. The narrator wryly comments:

“(This was perfectly true, the lady having bought a cheap and showy article on her way to the interview, with a general eye to bribery.)”

However, Mrs. Merdle insists that she is still very concerned about “Society”’s prejudices, and must make it clear to Fanny that any marriage between Fanny and her son would cause them to have nothing to do with their son, and would leave him a beggar. Amid much pouting and tossing of her head by Fanny, Mrs. Merdle says:

“Finally, after some high words and high spirit on the part of your sister, we came to the complete understanding that there was no danger; and your sister was so obliging as to allow me to present her with a mark or two of my appreciation at my dressmaker’s.”

Amy is anxious and troubled when she hears this, and Mrs. Merdle’s final action is to put something into Fanny’s hand as they leave. The parrot pronounces his own verdict on the whole proceedings:

“he tore at a claw-full of biscuit and spat it out, seemed to mock them with a pompous dance of his body without moving his feet, and suddenly turned himself upside down and trailed himself all over the outside of his golden cage, with the aid of his cruel beak and black tongue.”

And without demur Mrs. Merdle asserts:

“A more primitive state of society would be delicious to me.”

As they leave, Fanny asks Amy why she says nothing, and Amy says she is very sorry Fanny accepted anything from Mrs. Merdle. Fanny is scornful, saying that Amy has no self-respect, and would let herself and her family be trodden on. Mrs. Merdle is “false and insolent”. She looks down on them, and the least they can do is to make her pay for it.

Back at their lodgings, Fanny makes a great show of getting the meal ready, although it is Amy who really does it. She then goes on to tell Amy that if she despises her sister for being a dancer, and holds them all in contempt, then why did she make her one? It is all Amy’s doing, that she is a dancer in the first place and looked down upon by Mrs. Merdle and people like her. She carries on in a temper for a long time, bringing in Tip and their father too, and says that Amy should at least feel for him, knowing what he has undergone for so long. This cuts Amy to the quick, especially because of the night before, and she turns her back on Fanny’s outburst.

Fanny begins to feel sorry, and tells Amy that while she has been concerned with domestic matters, and shut up, Fanny has been out in society and has become proud and spirited; while Amy has been thinking of dinner and their clothes, Fanny has been thinking of the family’s honour.

Amy is not sure about this at all, in her heart. And their uncle seems to have no conception of what is going on, as he practises his clarionet. Little Dorrit hastens away, back to her father and the Marshalsea, where:

“The shadow of the wall was on every object.”

We are given a clue about this chapter in the first sentence, where the narrator comments that if Young John were a different sort of person, he could have written “a satire on family pride” about the Dorrits. And that is precisely what the author does here.

Tip, now at liberty, is not in the last interested in who paid his debts, but has got himself a promising job as a billiard-marker. He often visits the Marshalsea, and one thing slightly in his favour is that he “respected and admired his sister Amy” although “distinctly perceiving that she sacrificed her life to her father, and having no idea that she had done anything for himself”.

Tip and Fanny have learned well their father’s way of exaggerating their false connections to gentility; a “family skeleton”, to use whenever it is to their advantage:

“the more reduced and necessitous they were, the more pompously the skeleton emerged from its tomb; and that when there was anything particularly shabby in the wind, the skeleton always came out with the ghastliest flourish.”

Little Dorrit is on her way to see her sister Fanny, but when she gets to Mr. Cripples’s, she discovers that both her sister and her uncle have gone to the theatre where they work. The author paints a wonderfully atmospheric picture of the theatre for us, from the point of view of Amy: someone who has never seen the like, or had any information about it:

“Little Dorrit was almost as ignorant of the ways of theatres as of the ways of gold mines, and when she was directed to a furtive sort of door, with a curious up-all-night air about it, that appeared to be ashamed of itself and to be hiding in an alley, she hesitated to approach it.”

However she is encouraged by the fact that those around look quite similar to the inmates of the Marshalsea, who:

“made way for her to enter a dark hall—it was more like a great grim lamp gone out than anything else—where she could hear the distant playing of music and the sound of dancing feet. A man so much in want of airing that he had a blue mould upon him, sat watching this dark place from a hole in a corner, like a spider; and he told her that he would send a message up to Miss Dorrit”

Nearing her destination, accompanied by a woman who looks as though she needs ironing, Amy finds:

“a maze of dust, where a quantity of people were tumbling over one another, and where there was such a confusion of unaccountable shapes of beams, bulkheads, brick walls, ropes, and rollers, and such a mixing of gaslight and daylight, that they seemed to have got on the wrong side of the pattern of the universe.”

Fanny is most surprised to see her, “among the professionals” and goes on to say that quiet little thing though she is, Amy can find her way to any place. Fanny says that she would have never been able to do it, even though she knows so much more of the world. The narrator explains that:

“It was the family custom to lay it down as family law, that she was a plain domestic little creature, without the great and sage experience of the rest. This family fiction was the family assertion of itself against her services. Not to make too much of them.”

Fanny and Amy Dorrit backstage - Phiz

Amy tells her sister she has come because she wants to know more about the lady who gave Fanny a bracelet; she has not been quite easy since Fanny told her. There are various interruptions by theatrical callers, as Fanny is called to a dance rehearsal, but finally she is released along with all the other dancing girls (who too look as if they need ironing).

“something was rolled up or by other means got out of the way, and there was a great empty well before them, looking down into the depths of which Fanny said, ‘Now, uncle!’”

Frederick Dorrit feels most at home in the orchestra pit. All sorts of rumours are told about him, and the narrator tells us that it is quite a joke to the other members of the company, that this “pale phantom of a gentleman” lurks there with his clarionet, barely conscious of whatever else is going on outside himself:

Frederick Dorrit andhis clarionet - Sol Etynge Jnr. - 1871

Fanny has to call for him three or four times before he knows they are there, but they eventually set off.

Fanny:

“was pretty, and conscious, and rather flaunting; and the condescension with which she put aside the superiority of her charms, and of her worldly experience, and addressed her sister on almost equal terms, had a vast deal of the family in it.”

They walk on to a cook’s shop, where Frederick will have his dinner:

“a dirty shop window in a dirty street, which was made almost opaque by the steam of hot meats, vegetables, and pudding”

but which sells substantial hot meals. Fanny gives their uncle a shilling, and he disappears inside.

Fanny suggests they walk to Harley Street, Cavendish Square, (a most distinguished address, as the narrator points out). Since, she says, Amy is curious about her, she is taking her sister to meet Mrs. Merdle, the lady who gave her the bracelet, and who lives in the grandest house on the street.

When Fanny knocks on the door, it is opened by a heavily powdered footman, backed up by two more footmen with powder on their heads. The sisters are shown into:

“a spacious semicircular drawing-room, one of several drawing-rooms, where there was a parrot on the outside of a golden cage holding on by its beak, with its scaly legs in the air, and putting itself into many strange upside-down postures. This peculiarity has been observed in birds of quite another feather, climbing upon golden wires.”

This heavy clue tells us that the parrot is a character in its own right, and indeed during the whole of the following discourse, it is the parrot who seems to be the most honest and frank of all those present.

To Little Dorrit’s eyes, this room is far more splendid than any room she has ever imagined. Mrs. Merdle enters the room:

“The lady was not young and fresh from the hand of Nature, but was young and fresh from the hand of her maid. She had large unfeeling handsome eyes, and dark unfeeling handsome hair, and a broad unfeeling handsome bosom, and was made the most of in every particular.”

Fanny introduces her sister to Mrs. Merdle, and asks Mrs. Merdle to tell Amy how they happen to know each other. Mrs. Merdle hesitates, because of Little Dorrit’s age, but Fanny says that she is much older than she looks. We then get one of Mrs. Merdle’s many pronouncements on the sad mores and restrictions of “Society”, whereupon:

“The parrot had given a most piercing shriek, as if its name were Society and it asserted its right to its exactions.”

Mrs. Merdle continues:

“We know it is hollow and conventional and worldly and very shocking, but unless we are Savages in the Tropical seas (I should have been charmed to be one myself—most delightful life and perfect climate, I am told), we must consult it.”

and the parrot also continues to give its opinion on the worth of what Mrs. Merdle is saying.

We learn the story which Fanny wishes Amy to hear, with apposite interjections from the parrot, as to the accuracy of Mrs. Merdle’s posturing and reasons.

Mrs. Merdle says that her husband is very wealthy and his influence is very great. She also has a twenty-three year old son, who is gay, very impressionable, and fascinated by the stage. Because of this he became fascinated by Fanny, and when his mother heard of this she assumed Fanny was a dancer at the opera. When she had learned the truth, and that (as she put it) Fanny had, by refusing his advances, tempted him into wanting to marry her, she became most distressed. His mother said that the anguish she suffered was so acute that she went to visit Fanny for herself.

She recounts that Fanny had countered her objections, saying that her own family’s standing in the society in which her father moves, is as good, if not superior, to the Merdles’. Moreover it is acknowledged by everyone. (Of course she does not say where this “society” actually is.) Her own brother, Fanny says, “would not consider such a connection any honour.”

Mrs. Merdle says that she had been so delighted that they could discuss the subject frankly, that she had immediately taken a bracelet from her arm, and given it to Fanny as a mark of her appreciation. The narrator wryly comments:

“(This was perfectly true, the lady having bought a cheap and showy article on her way to the interview, with a general eye to bribery.)”

However, Mrs. Merdle insists that she is still very concerned about “Society”’s prejudices, and must make it clear to Fanny that any marriage between Fanny and her son would cause them to have nothing to do with their son, and would leave him a beggar. Amid much pouting and tossing of her head by Fanny, Mrs. Merdle says:

“Finally, after some high words and high spirit on the part of your sister, we came to the complete understanding that there was no danger; and your sister was so obliging as to allow me to present her with a mark or two of my appreciation at my dressmaker’s.”

Amy is anxious and troubled when she hears this, and Mrs. Merdle’s final action is to put something into Fanny’s hand as they leave. The parrot pronounces his own verdict on the whole proceedings:

“he tore at a claw-full of biscuit and spat it out, seemed to mock them with a pompous dance of his body without moving his feet, and suddenly turned himself upside down and trailed himself all over the outside of his golden cage, with the aid of his cruel beak and black tongue.”

And without demur Mrs. Merdle asserts:

“A more primitive state of society would be delicious to me.”

As they leave, Fanny asks Amy why she says nothing, and Amy says she is very sorry Fanny accepted anything from Mrs. Merdle. Fanny is scornful, saying that Amy has no self-respect, and would let herself and her family be trodden on. Mrs. Merdle is “false and insolent”. She looks down on them, and the least they can do is to make her pay for it.

Back at their lodgings, Fanny makes a great show of getting the meal ready, although it is Amy who really does it. She then goes on to tell Amy that if she despises her sister for being a dancer, and holds them all in contempt, then why did she make her one? It is all Amy’s doing, that she is a dancer in the first place and looked down upon by Mrs. Merdle and people like her. She carries on in a temper for a long time, bringing in Tip and their father too, and says that Amy should at least feel for him, knowing what he has undergone for so long. This cuts Amy to the quick, especially because of the night before, and she turns her back on Fanny’s outburst.

Fanny begins to feel sorry, and tells Amy that while she has been concerned with domestic matters, and shut up, Fanny has been out in society and has become proud and spirited; while Amy has been thinking of dinner and their clothes, Fanny has been thinking of the family’s honour.

Amy is not sure about this at all, in her heart. And their uncle seems to have no conception of what is going on, as he practises his clarionet. Little Dorrit hastens away, back to her father and the Marshalsea, where:

“The shadow of the wall was on every object.”

message 187:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 06, 2020 06:35AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I think this is my favourite chapter so far. It’s so packed with irony and humour. And here is an illustration which wouldn't fit! It is another of Little Dorrit Among the Professionals" and this time by Harry Furniss

I loved the mustiness Charles Dickens conveys of backstage, and how it appears to Amy. And now we have met the vain Mrs. Merdle—what an incorrigible snob! She seems incapable of saying anything without dissembling; even the parrot seem to find her out. (I love that—a brilliant touch!) The satirical parrot may be my favourite character :D

And Amy is coming into her own. We see her quiet strength here. Fanny well understands that she has done something not very honourable, and it is Amy who has made this clear to her. Fanny probably feels rather ashamed of herself now, but tries to bluff it out for what she calls the sake of family pride".

I loved the mustiness Charles Dickens conveys of backstage, and how it appears to Amy. And now we have met the vain Mrs. Merdle—what an incorrigible snob! She seems incapable of saying anything without dissembling; even the parrot seem to find her out. (I love that—a brilliant touch!) The satirical parrot may be my favourite character :D

And Amy is coming into her own. We see her quiet strength here. Fanny well understands that she has done something not very honourable, and it is Amy who has made this clear to her. Fanny probably feels rather ashamed of herself now, but tries to bluff it out for what she calls the sake of family pride".

And a little more …

About the “billiard marker”—Tip’s latest job. At the time of the novel, the game of billiards was very new. In fact the rules of the game were only established a few years later, in 1875 (by Neville Chamberlain).

When two gentlemen decided to play billiards, they must hire the table, the room, and the services of the marker. They paid a certain sum per game or hour, and could then use them without interruption.

The marker was a quite popular job, especially for young teenage boys. His job was to mark the game, hold the billiard rest, take the balls out of the pocket, and act as a referee if required. He was not supposed to do anything else at the same time. Records of the time however, showed that in many billiard-rooms a gentleman might enter the room, and order the marker to get him a brandy-and-soda, or beer, or change for a sovereign.

This was considered to be impertinent, and bad etiquette, just as if he had entered a gentleman’s dining-room and ordered his servant to run a message for him.

Somehow, I think Tip would have had no reluctance at not observing courtesies, and been someone who just followed whoever gave him the best gratuities (as his name suggests!)

About the “billiard marker”—Tip’s latest job. At the time of the novel, the game of billiards was very new. In fact the rules of the game were only established a few years later, in 1875 (by Neville Chamberlain).

When two gentlemen decided to play billiards, they must hire the table, the room, and the services of the marker. They paid a certain sum per game or hour, and could then use them without interruption.

The marker was a quite popular job, especially for young teenage boys. His job was to mark the game, hold the billiard rest, take the balls out of the pocket, and act as a referee if required. He was not supposed to do anything else at the same time. Records of the time however, showed that in many billiard-rooms a gentleman might enter the room, and order the marker to get him a brandy-and-soda, or beer, or change for a sovereign.

This was considered to be impertinent, and bad etiquette, just as if he had entered a gentleman’s dining-room and ordered his servant to run a message for him.

Somehow, I think Tip would have had no reluctance at not observing courtesies, and been someone who just followed whoever gave him the best gratuities (as his name suggests!)

Bionic Jean wrote: "Chapter 20:

Bionic Jean wrote: "Chapter 20:Tip and Fanny have learned well their father’s way of exaggerating their false connections to gentility; a “family skeleton”, to use whenever it is to their advantage:

“the more reduced and necessitous they were, the more pompously the skeleton emerged from its tomb; and that when there was anything particularly shabby in the wind, the skeleton always came out with the ghastliest flourish.” "

What they do show how they're good at it. Hopefully, Amy seems not fooled fully.

Yes, I think Amy is quick and bright :) She's probably the cleverest in her family. That could be one reason why Fanny and Tip just copy their father, in his bad habits, rather than thinking things out for themselves.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Yes, I think Amy is quick and bright :) She's probably the cleverest in her family. That could be one reason why Fanny and Tip just copy their father, in his bad habits, rather than thinking things..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Yes, I think Amy is quick and bright :) She's probably the cleverest in her family. That could be one reason why Fanny and Tip just copy their father, in his bad habits, rather than thinking things..."They really like to choose easy way.

Before this chapter, I was confused about why Amy chose to stay outside rather than going to her uncle. But now I can guess she didn't want to deal with her sister. Even though they know she works.

I was not surprised that she turned John Chivery down. At this point in the book I cannot imagine Little Dorrit as a wife, at least not while her father is living. But as mentioned earlier relating to Arthur and Pet, marriages were not always about love, but about a good match. And I agree Sara that John would be the perfect match for her. Where else would she find a husband that would dream of living in a prison for his wife?

I was not surprised that she turned John Chivery down. At this point in the book I cannot imagine Little Dorrit as a wife, at least not while her father is living. But as mentioned earlier relating to Arthur and Pet, marriages were not always about love, but about a good match. And I agree Sara that John would be the perfect match for her. Where else would she find a husband that would dream of living in a prison for his wife?

Dickens knew well what theaters looked like backstage. I like how he observes that some of the inhabitants seem just as shut up as those in the prison. (Many theaters have changed little backstage as far as clutter and crowded spaces, which is one reason why they can't open around the world right now.)

Dickens knew well what theaters looked like backstage. I like how he observes that some of the inhabitants seem just as shut up as those in the prison. (Many theaters have changed little backstage as far as clutter and crowded spaces, which is one reason why they can't open around the world right now.)

message 194:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 04, 2020 09:15AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin P wrote: "Dickens knew well what theaters looked like backstage ..."

Yes indeed. As Nisa listed in comment 1, this installment was originally published in May 1856. Two months earlier he had purchased the mansion in Rochester "Gads Hill Place" which he had always admired as a child. And here he put on many amateur theatricals with his family and friends.