Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit: Chapters 1 - 11

The Clennams definitely are in the imports business

The Clennams definitely are in the imports business“All our consignments have long been made to Rovinghams’ the commission-merchants”

and it is this English end of the business which Mrs Clennam oversees. England imported a lot of cloth and porcelain from China so the trade may be in these.

Ah, the imports business. I wonder if that connects them to Jean-Baptise?

Ah, the imports business. I wonder if that connects them to Jean-Baptise?I keep coming back to that prison cell in chapter one. There must have been a reason for it.

Debra, I am puzzled too about the nature of the Clennam business. They are moneylenders, but since all matters are handled by Mrs. Clennam only, looks like they are spread very thin - being both in China and Europe.

Debra, I am puzzled too about the nature of the Clennam business. They are moneylenders, but since all matters are handled by Mrs. Clennam only, looks like they are spread very thin - being both in China and Europe. Honestly, my impression is that Mr. Clennam the elder (Arthur's father) went to China to be as far away from his disagreeable wife as he could!

Helen wrote: "...Honestly, my impression is that Mr. Clennam the elder (Arthur's father) went to China to be as far away from his disagreeable wife as he could! "

Helen wrote: "...Honestly, my impression is that Mr. Clennam the elder (Arthur's father) went to China to be as far away from his disagreeable wife as he could! "lol

Helen wrote: "Mr. Clennam the elder (Arthur's father) went to China to be as far away from his disagreeable wife as he could..."

I love this excellent idea! :D

Susan - "The Clennams definitely are in the imports business

“All our consignments have long been made to Rovinghams’ the commission-merchants”

and it is this English end of the business which Mrs Clennam oversees"

Thanks for nailing this :)

I love this excellent idea! :D

Susan - "The Clennams definitely are in the imports business

“All our consignments have long been made to Rovinghams’ the commission-merchants”

and it is this English end of the business which Mrs Clennam oversees"

Thanks for nailing this :)

message 307:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Aug 30, 2022 08:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 6:

The Marshalsea Prison, we are told, used to be a debtor’s prison in the borough of Southwark (in South London):

“It was an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back, so that there were no back rooms; environed by a narrow paved yard, hemmed in by high walls duly spiked at top.”

Now however, thirty years later, it no longer stands there.

A main character in the novel, the narrator tells us:

“had been taken to the Marshalsea Prison, long before the day when the sun shone on Marseilles and on the opening of this narrative, a debtor with whom this narrative has some concern.”

He was:

“a very amiable and very helpless middle-aged gentleman, who was going out again directly … a shy, retiring man; well-looking, though in an effeminate style; with a mild voice, curling hair, and irresolute hands—rings upon the fingers in those days—which nervously wandered to his trembling lip”.

All the prisoners, the turnkey ironically observes, were going out directly, and some were reluctant to unpack their belongings.

Arriving the next day, are this prisoner’s family: his wife and their two children. The prisoner is worried about his wife, and with good reason, for six months later she gives birth to a tiny child

There is a doctor in the Marshalsea, who is none too clean, and:

“amazingly shabby, in a torn and darned rough-weather sea-jacket, … the dirtiest white trousers conceivable by mortal man, carpet slippers, and no visible linen.”

Also, to help is Mrs. Bangham, a charwoman and messenger to the outside world (as she was no longer a prisoner), who “had volunteered her services as fly-catcher and general attendant …

“Three or four hours passed; the flies fell into the traps by hundreds; and at length one little life, hardly stronger than theirs, appeared among the multitude of lesser deaths.”

A diminutive child is born. The doctor and Mrs. Bangham celebrate with brandy, and the prisoner has fewer rings on his fingers after this event, as payment for their services.

The baby grows up in the Marshalsea: “everybody knew the baby, and claimed a kind of proprietorship in her.” Her father is so genteel, with educated manners, and speaking several languages, that the turnkey is quite proud of him. He begins to refer to him as the “Father of the Marshalsea”, and all new-comers are presented to him.

The Father of the Marshalsea receives them graciously, and welcomes them to the Marshalsea. A habit begins whereby those leaving would enclose a few silver coins “With the compliments of a collegian taking leave” which the Father of the Marshalsea receives as his just tribute. In turn he establishes the custom of attending selected “collegians” to the gate, and taking leave of them there, which enables the transactions to take place more naturally.

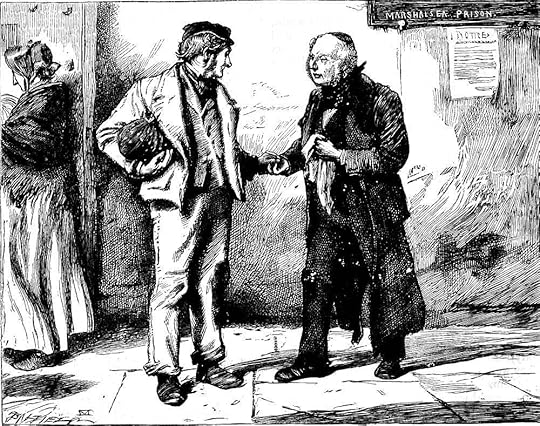

Father of the Marshalsea and Plornish the plasterer - James Mahoney

When they have been there eight years he wife of the Father of the Marshalsea dies. She was fragile, and had languished away. The Father of the Marshalsea shuts himself up in his room for a fortnight after her death, but after a month or two, he ventures into the courtyard again, and the children are back to playing in the yard.

The turnkey too begins to fail, and dies.

The Marshalsea Prison, we are told, used to be a debtor’s prison in the borough of Southwark (in South London):

“It was an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back, so that there were no back rooms; environed by a narrow paved yard, hemmed in by high walls duly spiked at top.”

Now however, thirty years later, it no longer stands there.

A main character in the novel, the narrator tells us:

“had been taken to the Marshalsea Prison, long before the day when the sun shone on Marseilles and on the opening of this narrative, a debtor with whom this narrative has some concern.”

He was:

“a very amiable and very helpless middle-aged gentleman, who was going out again directly … a shy, retiring man; well-looking, though in an effeminate style; with a mild voice, curling hair, and irresolute hands—rings upon the fingers in those days—which nervously wandered to his trembling lip”.

All the prisoners, the turnkey ironically observes, were going out directly, and some were reluctant to unpack their belongings.

Arriving the next day, are this prisoner’s family: his wife and their two children. The prisoner is worried about his wife, and with good reason, for six months later she gives birth to a tiny child

There is a doctor in the Marshalsea, who is none too clean, and:

“amazingly shabby, in a torn and darned rough-weather sea-jacket, … the dirtiest white trousers conceivable by mortal man, carpet slippers, and no visible linen.”

Also, to help is Mrs. Bangham, a charwoman and messenger to the outside world (as she was no longer a prisoner), who “had volunteered her services as fly-catcher and general attendant …

“Three or four hours passed; the flies fell into the traps by hundreds; and at length one little life, hardly stronger than theirs, appeared among the multitude of lesser deaths.”

A diminutive child is born. The doctor and Mrs. Bangham celebrate with brandy, and the prisoner has fewer rings on his fingers after this event, as payment for their services.

The baby grows up in the Marshalsea: “everybody knew the baby, and claimed a kind of proprietorship in her.” Her father is so genteel, with educated manners, and speaking several languages, that the turnkey is quite proud of him. He begins to refer to him as the “Father of the Marshalsea”, and all new-comers are presented to him.

The Father of the Marshalsea receives them graciously, and welcomes them to the Marshalsea. A habit begins whereby those leaving would enclose a few silver coins “With the compliments of a collegian taking leave” which the Father of the Marshalsea receives as his just tribute. In turn he establishes the custom of attending selected “collegians” to the gate, and taking leave of them there, which enables the transactions to take place more naturally.

Father of the Marshalsea and Plornish the plasterer - James Mahoney

When they have been there eight years he wife of the Father of the Marshalsea dies. She was fragile, and had languished away. The Father of the Marshalsea shuts himself up in his room for a fortnight after her death, but after a month or two, he ventures into the courtyard again, and the children are back to playing in the yard.

The turnkey too begins to fail, and dies.

message 308:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 10:40AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

A lot of this chapter is in retrospect, “long before” the first chapter, the narrator tells us. In fact Charles Dickens jumps to and fro, between different times. We go back into the past and then jumping between the present of the novel, and the past again. The next one does this even more. I think this is quite a modern way of writing, not telling things in strict chronological order, giving us more interest. And it tells us quite a lot of information.

We actually meet the title character, at last, (view spoiler) :) When her mother dies, she is so small that all she can do is sit with her father, who is nicknamed “The Father of the Marshalsea” (first as a joke, and then as a mark of respect because he is after all so gentil) but by the time she is sixteen she is thinking for them all, and running the “household”.

It’s yet another sort of dysfunctional family, with a tiny “little mother”—she will even be called this by another character—and three adult “children” (her father, brother (view spoiler) sister (view spoiler) and Uncle). Yet it is the youngest who is the tiny child-adult!

Charles Dickens is so good at depicting these characters with a sort of learned helplessness—which proves very convenient for them! What great leeches Dickens can draw: Mr. Dorrit, Mr. Micawber. Then there’s Harold Skimpole from “Bleak House”, who was a sort of counterweight to Mr. Dick, whom we know and love from “David Copperfield”, but who was a truly simple-minded person.

Edit:

Names put under spoilers, as Jenny pointed out that Charles Dickens has not used them in this chapter.

We actually meet the title character, at last, (view spoiler) :) When her mother dies, she is so small that all she can do is sit with her father, who is nicknamed “The Father of the Marshalsea” (first as a joke, and then as a mark of respect because he is after all so gentil) but by the time she is sixteen she is thinking for them all, and running the “household”.

It’s yet another sort of dysfunctional family, with a tiny “little mother”—she will even be called this by another character—and three adult “children” (her father, brother (view spoiler) sister (view spoiler) and Uncle). Yet it is the youngest who is the tiny child-adult!

Charles Dickens is so good at depicting these characters with a sort of learned helplessness—which proves very convenient for them! What great leeches Dickens can draw: Mr. Dorrit, Mr. Micawber. Then there’s Harold Skimpole from “Bleak House”, who was a sort of counterweight to Mr. Dick, whom we know and love from “David Copperfield”, but who was a truly simple-minded person.

Edit:

Names put under spoilers, as Jenny pointed out that Charles Dickens has not used them in this chapter.

message 309:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 04:27AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more …

THE MARSHALSEA PRISON

As we can see, the Marshalsea Prison is a monument to the lack of money. And it really existed.

As Mona mentioned, Charles Dickens’s own father was sent there in 1824, when Dickens was 12, for a debt to a baker. As a result, young Charles was forced to leave school, to work in a blacking factory. He based several of his characters on this experience, which he could never forget. We've already read about Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield, but the most direct parallel is Mr. Dorrit, who is in the Marshalsea for debts so complex, that no one can fathom them, nor how to get him released.

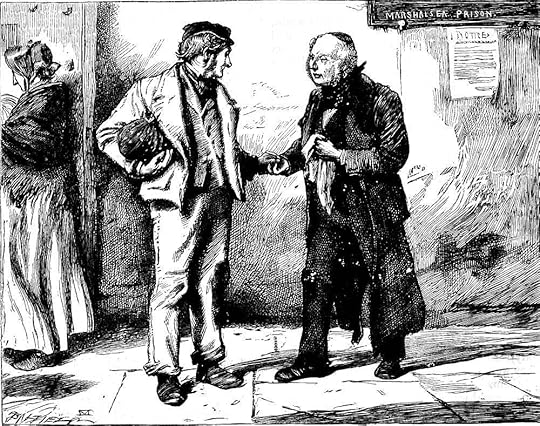

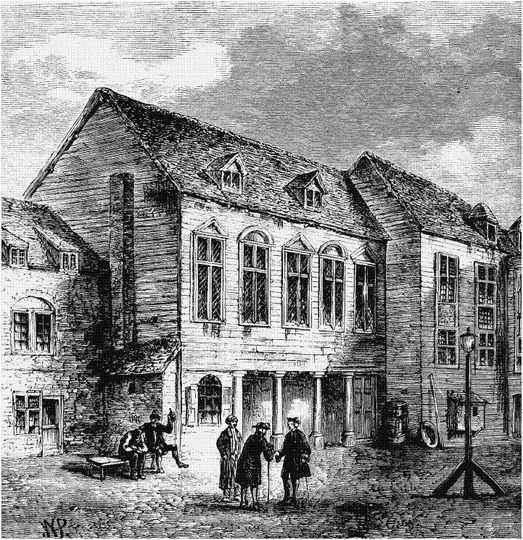

An 18th century engraving of the Marshalsea prison

The Marshalsea, in operation from 1373–1842, was a notorious prison in Southwark, London, just south of the River Thames. (At that time it was in the county of Surrey). The area was known for its travellers and inns, and because of this population there was poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres (including William Shakespeare’s "The Globe” which has now been rebuilt) and, inevitably, prisons.

In 1796 there were five prisons in the district of Southwark—the “Clink”, “King’s Bench”, “Borough Compter”, “White Lion” and the “Marshalsea” whereas there were 18 in the whole of London.

Many prisoners were incarcerated in the Marshalsea over the centuries. They included men who were accused of crimes at sea, and political figures charged with sedition. It became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London’s debtors. Incredibly, over half the population of England’s prisons in the 18th century were in jail because of debt

Of course the irony was that the only way to survive there was by purchasing items to keep you fed and alive. And as for getting out—it was well nigh impossible as how could those incarcerated earn any money?

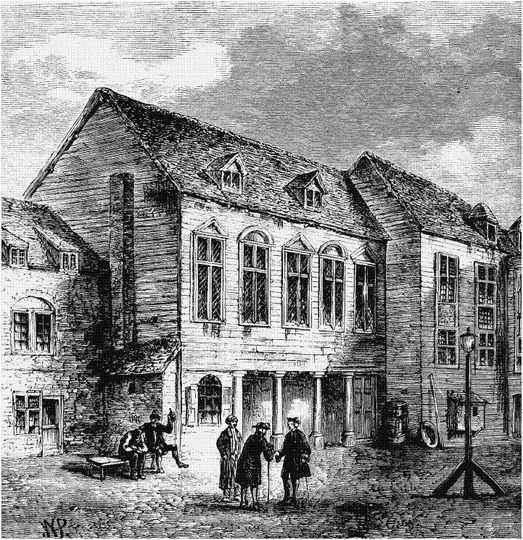

The “Marshalsea” of Charles Dickens’s time, and where the Dorrits lived, was not the original building. In fact the Marshalsea occupied two buildings on the same street in Southwark. The first dated back to the 14th century at what would now be 161 Borough High Street. By the late 16th century the building was crumbling, so in 1799 it was rebuilt 130 yards south, on what is now 211 Borough High Street.

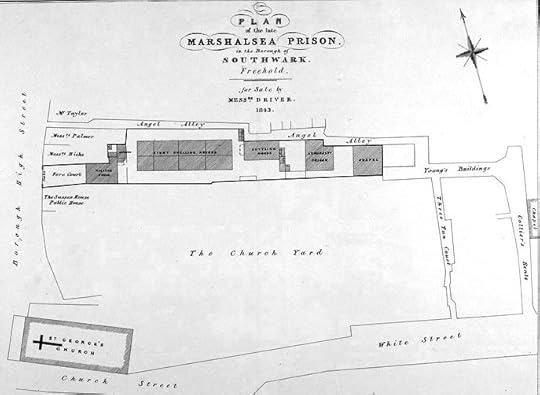

Plan of the 1843 Marshalsea Prison

The majority of the inmates of both prisons were debtors. They could be imprisoned there for a debt of just 40 shillings (two pounds).

The descriptions we will get in Little Dorrit are based on fact. The Marshalsea had a bar, run by the governor’s wife, and a chandler’s shop, which sold candles, soap and a little food. In 1728 this was by a couple who were both prisoners in the Marshalsea. There was a coffee shop, also run by a long-term prisoner, and a steak house called “Titty Doll’s” run by another prisoner and his wife. Other shops included a tailor and a barber.

There were two “sides” and prisoners from the master’s side could hire prisoners from the common side to act as their servants.

It sounds as though living conditions in this “common” side were horrific. In 1639, prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without any space to lie down. This led to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a “bull’s pizzle” (a whip made from a bull’s penis), or tortured with thumbscrews and a “skullcap”: a vice for the head, that weighed 12 lb.

What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the strong room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadavers awaiting burial and piles of night soil. Charles Dickens described it as: “dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats.” One apparently diabetic army officer had been ejected from the common side, because inmates had complained about the smell of his urine. So he was put in the strong room, and had his face eaten by rats within hours of his death, according to a witness.

Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s. According to him Charles Dickens did not exaggerate. If anything, “he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities.”

A sobering thought indeed.

THE MARSHALSEA PRISON

As we can see, the Marshalsea Prison is a monument to the lack of money. And it really existed.

As Mona mentioned, Charles Dickens’s own father was sent there in 1824, when Dickens was 12, for a debt to a baker. As a result, young Charles was forced to leave school, to work in a blacking factory. He based several of his characters on this experience, which he could never forget. We've already read about Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield, but the most direct parallel is Mr. Dorrit, who is in the Marshalsea for debts so complex, that no one can fathom them, nor how to get him released.

An 18th century engraving of the Marshalsea prison

The Marshalsea, in operation from 1373–1842, was a notorious prison in Southwark, London, just south of the River Thames. (At that time it was in the county of Surrey). The area was known for its travellers and inns, and because of this population there was poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres (including William Shakespeare’s "The Globe” which has now been rebuilt) and, inevitably, prisons.

In 1796 there were five prisons in the district of Southwark—the “Clink”, “King’s Bench”, “Borough Compter”, “White Lion” and the “Marshalsea” whereas there were 18 in the whole of London.

Many prisoners were incarcerated in the Marshalsea over the centuries. They included men who were accused of crimes at sea, and political figures charged with sedition. It became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London’s debtors. Incredibly, over half the population of England’s prisons in the 18th century were in jail because of debt

Of course the irony was that the only way to survive there was by purchasing items to keep you fed and alive. And as for getting out—it was well nigh impossible as how could those incarcerated earn any money?

The “Marshalsea” of Charles Dickens’s time, and where the Dorrits lived, was not the original building. In fact the Marshalsea occupied two buildings on the same street in Southwark. The first dated back to the 14th century at what would now be 161 Borough High Street. By the late 16th century the building was crumbling, so in 1799 it was rebuilt 130 yards south, on what is now 211 Borough High Street.

Plan of the 1843 Marshalsea Prison

The majority of the inmates of both prisons were debtors. They could be imprisoned there for a debt of just 40 shillings (two pounds).

The descriptions we will get in Little Dorrit are based on fact. The Marshalsea had a bar, run by the governor’s wife, and a chandler’s shop, which sold candles, soap and a little food. In 1728 this was by a couple who were both prisoners in the Marshalsea. There was a coffee shop, also run by a long-term prisoner, and a steak house called “Titty Doll’s” run by another prisoner and his wife. Other shops included a tailor and a barber.

There were two “sides” and prisoners from the master’s side could hire prisoners from the common side to act as their servants.

It sounds as though living conditions in this “common” side were horrific. In 1639, prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without any space to lie down. This led to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a “bull’s pizzle” (a whip made from a bull’s penis), or tortured with thumbscrews and a “skullcap”: a vice for the head, that weighed 12 lb.

What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the strong room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadavers awaiting burial and piles of night soil. Charles Dickens described it as: “dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats.” One apparently diabetic army officer had been ejected from the common side, because inmates had complained about the smell of his urine. So he was put in the strong room, and had his face eaten by rats within hours of his death, according to a witness.

Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s. According to him Charles Dickens did not exaggerate. If anything, “he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities.”

A sobering thought indeed.

Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s. According to him, Charles Dickens did not exaggerate. If anything, “he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities.”."

Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s. According to him, Charles Dickens did not exaggerate. If anything, “he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities.”."It is really sad to know this place and what he said about it close to reality (or even downplayed). But I always happy to learn new facts. Jean, thanks for sharing all this informations and summaries which make the buddy read irreplaceable for Dickens's books.

And finally we begin to learn things about the main character's story :)). I'm curious when Dickens will let us know about the conections with first two chapter characters.

I highlighted in my e-book the bitter comment of the shabby doctor who delivers the baby: "We have got to the bottom, we can’t fall, and what have we found? Peace” Dickens uses it to compare the doctor to Mr Dorrit who "languidly slipped into this smooth descent".

I highlighted in my e-book the bitter comment of the shabby doctor who delivers the baby: "We have got to the bottom, we can’t fall, and what have we found? Peace” Dickens uses it to compare the doctor to Mr Dorrit who "languidly slipped into this smooth descent". Once more I see an effective criticism of the prison as a place where people who made a minor mistake like a debt, are not helped to take back control of their life. Thank you Jean for the information about the Marshalsea prison.

I wonder how Little Dorrit feels to have a father who is a gentleman, but at the same time accepts charity money. What a conflict there may be in her feelings towards her father: pride for her genteel father and shame for the beggar.

Nisa wrote: "Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real pr..."

Nisa wrote: "Trey Philpotts, a Literature professor at a Florida University, has written a companion to Little Dorrit, and he asserts that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real pr..."Nisa, that last bit struck me too

Not intending to be political, but I wanted to point out that we aren't as removed from those days as we would wish. It seems like we would never do such cruel and ineffective things today as imprison people for debt. But in the U.S. today, many people are held in jails awaiting trial, even though they may be innocent, because they can't afford bail or a good lawyer. People are arrested for unpaid parking or traffic fines, and how are they supposed to pay them when they are locked up? Prisoners and their families are charged exorbitant rates for things like telephone calls. And in at least one state, former felons are being told they can't vote until they pay past fines, and apparently it's not easy to determine how much each person's fine is. That last part is very Dickensian, reminding me of the trickiness of the law in several of his books.

Not intending to be political, but I wanted to point out that we aren't as removed from those days as we would wish. It seems like we would never do such cruel and ineffective things today as imprison people for debt. But in the U.S. today, many people are held in jails awaiting trial, even though they may be innocent, because they can't afford bail or a good lawyer. People are arrested for unpaid parking or traffic fines, and how are they supposed to pay them when they are locked up? Prisoners and their families are charged exorbitant rates for things like telephone calls. And in at least one state, former felons are being told they can't vote until they pay past fines, and apparently it's not easy to determine how much each person's fine is. That last part is very Dickensian, reminding me of the trickiness of the law in several of his books.

message 315:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 08:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Of course there are many injustices today, and "the trickiness of the law" as you put it Robin is still present. Charles Dickens will feature this a lot, in Little Dorrit.

However, I doubt whether the Marshalsea Prison is really comparable with present day conditions. Prisoners lying in leg-irons next to corpses? A sewer which is never cleaned, and full of rats and sometimes "several barrow fulls of dung" No beds? Women left alone to give birth in these conditions? I'll quote one case verbatim:

"Bliss was left in the strong room for three weeks wearing a skullcap (a heavy vice for the head), thumb screws, iron collar, leg irons, and irons round his ankles called sheers. One witness said the swelling in his legs was so bad that the irons on one side could no longer be seen for overflowing flesh. His wife, who was able to see him through a small hole in the door, testified that he was bleeding from the mouth and thumbs. He was given a small amount of food but the skullcap prevented him from chewing; he had to ask another prisoner, Susannah Dodd, to chew his meat for him. He was eventually released from the prison, but his health deteriorated and he died in St. Thomas's Hospital."

No, these are different days, at least in a developed country. And the Dorrits must have felt very fortunate to be on the Masters side, (with all the little shops which I described in my post) rather than the commons side.

I liked your quotation Milena, which showed a sort of resignation to their fate. And both you and Nisa will be pleased to know that we learn much more about Little Dorrit herself in the next chapter, which follows on in the same way, darting about from one time period to another.

However, I doubt whether the Marshalsea Prison is really comparable with present day conditions. Prisoners lying in leg-irons next to corpses? A sewer which is never cleaned, and full of rats and sometimes "several barrow fulls of dung" No beds? Women left alone to give birth in these conditions? I'll quote one case verbatim:

"Bliss was left in the strong room for three weeks wearing a skullcap (a heavy vice for the head), thumb screws, iron collar, leg irons, and irons round his ankles called sheers. One witness said the swelling in his legs was so bad that the irons on one side could no longer be seen for overflowing flesh. His wife, who was able to see him through a small hole in the door, testified that he was bleeding from the mouth and thumbs. He was given a small amount of food but the skullcap prevented him from chewing; he had to ask another prisoner, Susannah Dodd, to chew his meat for him. He was eventually released from the prison, but his health deteriorated and he died in St. Thomas's Hospital."

No, these are different days, at least in a developed country. And the Dorrits must have felt very fortunate to be on the Masters side, (with all the little shops which I described in my post) rather than the commons side.

I liked your quotation Milena, which showed a sort of resignation to their fate. And both you and Nisa will be pleased to know that we learn much more about Little Dorrit herself in the next chapter, which follows on in the same way, darting about from one time period to another.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Of course there are many injustices today, and "the trickiness of the law" as you put it Robin is still present. Charles Dickens will feature this a lot, in [book:Little Dorrit|3125..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Of course there are many injustices today, and "the trickiness of the law" as you put it Robin is still present. Charles Dickens will feature this a lot, in [book:Little Dorrit|3125..."Good point, Jean, I didn't mean to imply physical conditions now are similar to the Marshalsea, just the underlying irrationality of expecting locked-up prisoners to come up with money they owe. It does seem that debtors who had some resources were better treated. And we see that the Father of the Marshalsea was a model citizen and never caused any disciplinary problems. I can see how a baby born into the prison would be a kind of pet or mascot even for the jailers.

The baby's mother seems to have succumbed to what I call Beautiful Victorian Wasting Disease, no messy symptoms. On the other hand, it's not unrealistic that a woman with underlying health conditions, poor nutrition, etc. would waste away after a birth. I suppose that contagious diseases were rampant in a place like that. It's kind of amazing that a small baby survived.

message 317:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 02:38PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin P wrote: "Mrs. Dorrit seems to have succumbed to what I call Beautiful Victorian Wasting Disease ..."

Believe it or not Robin, I actually thought of you as I read that part! :D (I'd never heard the term before you coined it, in one of the threads.) But yes, I agree, she had more reason to die than a middle class Victorian heroine in a comfortable house. Death of both mother and child must have been common, but as she was well on in her pregnancy, when they were taken to the Marshalsea, the baby was actually born.

"It's kind of amazing that a small baby survived." Yes, she must have seemed like a little miracle - a pretty little caged bird. To me, it seems totally beliveable that she would stay as a diminutive person, given the poor nutrition etc.

Believe it or not Robin, I actually thought of you as I read that part! :D (I'd never heard the term before you coined it, in one of the threads.) But yes, I agree, she had more reason to die than a middle class Victorian heroine in a comfortable house. Death of both mother and child must have been common, but as she was well on in her pregnancy, when they were taken to the Marshalsea, the baby was actually born.

"It's kind of amazing that a small baby survived." Yes, she must have seemed like a little miracle - a pretty little caged bird. To me, it seems totally beliveable that she would stay as a diminutive person, given the poor nutrition etc.

Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!

Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!

Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!"

Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!"I was curious about that also. I assumed that it was about Little Dorrit's family and the baby was Little Dorrit, but my book does not actually come out and say so.

Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!"

Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!"I was wondering the same thing.

message 321:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 10:56AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!"

No, good point. I'll edit my summary to miss out (view spoiler) and amend all the references.

It's difficult to paraphrase without a little interpretation, and sometimes, to be honest, I think it would help! But you are quite correct.

No, good point. I'll edit my summary to miss out (view spoiler) and amend all the references.

It's difficult to paraphrase without a little interpretation, and sometimes, to be honest, I think it would help! But you are quite correct.

Bookworman wrote: "What's the most powerful part of this chapter for me the description of Mrs. Clennam regarding reparation and restitution. "Thus was she always balancing her bargains with the Majesty of heaven, po..."

Bookworman wrote: "What's the most powerful part of this chapter for me the description of Mrs. Clennam regarding reparation and restitution. "Thus was she always balancing her bargains with the Majesty of heaven, po..."I was also struck by Mrs. Clennam's ideas about "reparation and restitution". It allows her to do bad things because she will strike some kind of bargain with God later and she will have a clear conscience.

message 323:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 10:44AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Katy and Debra - I was in the middle of doing it when you posted. I'm sorry if my summary inadvertently spoilt anything :(

About Arthur leaving the business, I did not have a problem with the timing. He may have come to that conclusion during the time after his father's death when he was settling the business affairs and only made a decision shortly before he went home. Since it seems that he meant to advise his mother to get out of the business also, it would make more sense to talk to her in person (in my opinion). Actually, I think it would have been harder for him to have that conversation face to face than to tell her in a letter.

About Arthur leaving the business, I did not have a problem with the timing. He may have come to that conclusion during the time after his father's death when he was settling the business affairs and only made a decision shortly before he went home. Since it seems that he meant to advise his mother to get out of the business also, it would make more sense to talk to her in person (in my opinion). Actually, I think it would have been harder for him to have that conversation face to face than to tell her in a letter.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Katy and Debra - I was in the middle of doing it when you posted. I'm sorry if my summary inadvertently spoilt anything :("

Bionic Jean wrote: "Katy and Debra - I was in the middle of doing it when you posted. I'm sorry if my summary inadvertently spoilt anything :("No problem Jean, it didn't spoil anything. Like Debra, I just assumed I missed something. And it's perfectly understandable. I am very appreciative of your summaries.

message 327:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 10:55AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The next chapter follows on naturally from this one, which is quite unusual for Charles Dickens.

The action again jumps to and fro, between different times, as I said. It is in that chapter that the names are - gradually - revealed. But it's all quite subtle.

The action again jumps to and fro, between different times, as I said. It is in that chapter that the names are - gradually - revealed. But it's all quite subtle.

Same as Debra Jean, I had guessed and was just wondering. It did not spoil anything at all :)

Same as Debra Jean, I had guessed and was just wondering. It did not spoil anything at all :)Katy, on re reading chapter 5 a little closer, I see it had not been as long since his fathers death as I thought, so I can understand his timing a little better now.

I also find it hard to understand how debtors were supposed to find the money to get out while incarcerated maybe the ones who had the shops could, but not the rest. For the "master" side, I think the idea behind was that family and friends would pay the debt for the loves one to get out like we saw in David Copperfield and with John Dickens. It's also a little bit crazy that a whole family could live on the premise.

I also find it hard to understand how debtors were supposed to find the money to get out while incarcerated maybe the ones who had the shops could, but not the rest. For the "master" side, I think the idea behind was that family and friends would pay the debt for the loves one to get out like we saw in David Copperfield and with John Dickens. It's also a little bit crazy that a whole family could live on the premise.I expected the mother to die after childbirth with the insane conditions to have a baby, but she lived another 8 years so I don't think it's related. The malnutrition would make the children living there small and sickly.

I am keeping up with the reading, but have been too sad this weekend to comment.

I am keeping up with the reading, but have been too sad this weekend to comment. Something we know is deeply wrong within Arthur’s home. We suspect there is something that happened in the past, and that it involves the Father of the Marshalsea. We also suspect Flintwich of taking advantage of Mrs. Clennam. We also make the intuitive leap that the baby born in the debtor’s prison is the young seamstress spending much of her day tucked in corners at the Clennam house. We await confirmation of all our suppositions.

This reminder of the debtor’s system in England, I always think of it as a looming threat over many characters in the novels of Dickens, a person would never feel safe in the world after having such a seismic event happen to them. My daughter and I have been discussing how this has a new version these days as we read The New Jim Crow together. Someone is always willing to take advantage of the disenfranchised. I always thought the system of the debtor’s prison was highly impractical and illogical way of dealing with the problem, it seems to have left everyone involved dissatisfied.

France-Andrée wrote: "I expected the mother to die after childbirth with the insane conditions to have a baby, but she lived another 8 years so I don't think it's related ..."

Yes, good point, We are also told that she had gone "upon a visit to a poor friend and old nurse in the country and died there". I wonder if this is ever followed up.

She had "long been languishing away of her own inherent weakness" though, and with the worry and appalling nutrition and conditions in the prison, would be almost bound to have an undersized baby.

Yes, good point, We are also told that she had gone "upon a visit to a poor friend and old nurse in the country and died there". I wonder if this is ever followed up.

She had "long been languishing away of her own inherent weakness" though, and with the worry and appalling nutrition and conditions in the prison, would be almost bound to have an undersized baby.

message 332:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 20, 2020 01:19PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Kim wrote: "I am keeping up with the reading, but have been too sad this weekend to comment ..."

I'm so sorry you have been sad, Kim, and really hope that things improve for you.

That is partly what we are here for, to distract you with ... well maybe not Dickensian humour at the moment, but at least with the engrossing dark suspicions in Little Dorrit that you have pointed out. I hope you keep reading, and just come in with comments here when you feel like it :)

I'm so sorry you have been sad, Kim, and really hope that things improve for you.

That is partly what we are here for, to distract you with ... well maybe not Dickensian humour at the moment, but at least with the engrossing dark suspicions in Little Dorrit that you have pointed out. I hope you keep reading, and just come in with comments here when you feel like it :)

Bionic Jean wrote: "Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Jenny wrote: "Jean, does your edition actually name the family in this chapter? Mine does not, but ot was rather obvious from the lead in from the last chapter that it was her family. Just curious!..."I edited my comments also to reflect this.

Thank you Robin! All will become clear tomorrow anyway, and I'm pretty sure Charles Dickens meant us to guess. He just liked to play us along a bit :)

Kim, I hope your sadness dissipates and smiles reign! Hugs to you.

Kim, I hope your sadness dissipates and smiles reign! Hugs to you. I found chapter 6 a difficult one to read and understand at first and I think part of that is due to the time changes that Dickens employs, as you state, Jean. I re-read this chapter and got a clearer picture of events.

Dickens uses the technique of very long, run-on sentences with the commas, semi-colons, and parentheses as if trying to get all his thoughts, descriptions, and the social and political implications of the past into the story as background information and that still echo in the present time of the novel, as well as Dickens' own time. The narrator's comments about how "somebody came from some Office to go through some form of overlooking something which neither he nor anybody else knew anything about"...as "truly British occasions" ... "epitomizing the administration of most of the public affairs in our right little, tight little island," were directed to the time of the Marshalsea, to the time in Marseilles (he references chapter 1) and also to Dickens' own time. Bureaucracy, administrative red tape and corruption are timeless.

In chapter 6 the narrator connects us to the past in telling the history of the Marshalsea, to the time in chapter 1 by mentioning the events we read about in Marseilles, and at the end of chapter 5 to the quest of Arthur Clennam to watch and learn about Little Dorrit in the current time of the story. I'm wondering now if Clennam's "watching" her really means "spying" on her. Dickens would not talk about the prison unless somehow connected to both these characters.

As we start chapter seven, we have a lot of loose threads, or juggler’s balls, dancing around in our heads. We don’t know what is important to remember, yet. I’m enjoying the start of Little Dorrit and look forward to your great introductions to each chapter, Jean, and everyone’s comments.

As we start chapter seven, we have a lot of loose threads, or juggler’s balls, dancing around in our heads. We don’t know what is important to remember, yet. I’m enjoying the start of Little Dorrit and look forward to your great introductions to each chapter, Jean, and everyone’s comments.

message 338:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 21, 2020 03:23AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Thank you Kathleen! Very true ... and here is the next one. I must have been crossposting with you :)

Elizabeth I really enjoyed all your observations. "Our right little, tight little, island" struck a chord with me too. Some things are timeless in some ways. I'll pick up on the other after today's chapter, as they really form 2 parts of a whole. Of course Charles Dickens's original readers would probably have read them like that, as they belong in the same installment.

So without further ado, let's move on to the next chapter.

Elizabeth I really enjoyed all your observations. "Our right little, tight little, island" struck a chord with me too. Some things are timeless in some ways. I'll pick up on the other after today's chapter, as they really form 2 parts of a whole. Of course Charles Dickens's original readers would probably have read them like that, as they belong in the same installment.

So without further ado, let's move on to the next chapter.

message 339:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 21, 2020 03:26AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 7:

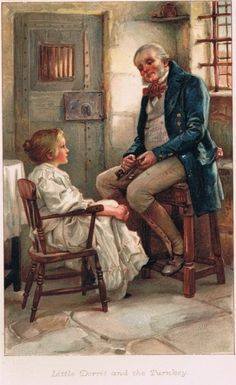

We now concentrate our attention on the baby, “The Child of the Marshalsea”. She has been “handed down among the generations of collegians”, and the turnkey is her godfather.

The Child of the Marshalsea soon learns that although she and her brother and sister may venture out, her father can not. Wistful and wondering:

“With a pitiful and plaintive look for everything, indeed, but with something in it for only him that was like protection … With a pitiful and plaintive look for her wayward sister; for her idle brother; for the high blank walls; for the faded crowd they shut in; for the games of the prison children as they whooped and ran, and played at hide-and-seek, and made the iron bars of the inner gateway ‘Home.’”

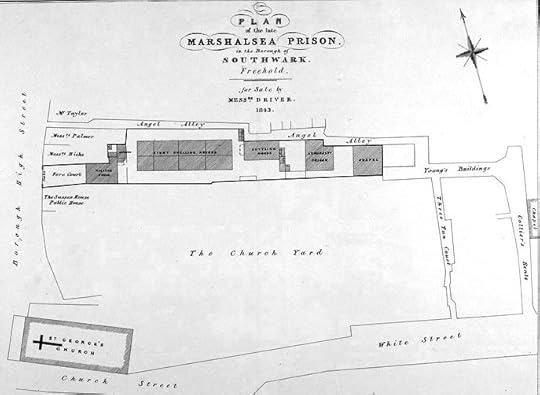

The Child of the Marshalsea and the Turnkey - Arthur A. Dixon 1905

She reaches the age of eight. The turnkey is like another father to her, taking her out on little expeditions to the country, so that she can see the world outside, and experience grass, trees and flowers. The turnkey wants to leave his money to this Child of the Marshalsea, but although he had been advised to settle it “strictly on herself” nobody could tell him how it could remain secure in her hands, if she had wanted to give it away, so he dies intestate, when she is sixteen.

But the narrator tells us that long before that, the Father of the Marshalsea had come to rely on her quiet strength, as she sat beside him:

“she drudged on, until recognised as useful, even indispensable … She took the place of eldest of the three, in all things but precedence; was the head of the fallen family; and bore, in her own heart, its anxieties and shames.”

It is the Child of the Marshalsea who takes care of them all. She begins to do the family accounts at thirteen, and looks for opportunities for her family within the prison. She always prefaces her appeals with:

“‘If you please, I was born here, sir.” and nobody can resist. She asks a new prisoner, who is a dancing instructor, to give her older sister lessons. He is happy to do this, and her sister learns quickly, well enough to become a dancer. She also asks a seamstress to teach her how to do needlework, and soon becomes adept at this.

The two sisters are now able to go out and earn a little money, although they have to keep it secret from their father, who is keeping up the fiction of gentility, and would be mortified if he knew they worked for a living. The older sister also goes to live with her uncle, to facilitate this:

“He had been a very indifferent musical amateur in his better days; and when he fell with his brother, resorted for support to playing a clarionet as dirty as himself in a small Theatre Orchestra. It was the theatre in which his niece became a dancer;”

The challenge comes with her brother. The Child of the Marshalsea arranges many jobs for him, but he tires of them all, and always ends up “cutting” just about everything. She even pinches and scrapes enough together to pay for a passage to Canada. But he gets no further than Liverpool, and never gets on the ship. He arrives back at the Marshalsea “in rags, without shoes, and much more tired than ever.”

What’s more, although her brother claims to have started a new job, he is soon in the Marshalsea on his own account—as a prisoner. The Child of the Marshalsea, whom we now know is called “Amy”, begs him not to tell the truth to their father, because she thinks the knowledge would kill him. So the fiction is kept up by all:

“the collegians, with a better comprehension of the pious fraud than Tip, supported it loyally.”

We learn that “Tip” is Amy’s older brother, Edward. He was called Teddy when younger, and then eventually “Tip”. Her older sister is called ”Fanny”.

Amy herself, never lets anyone in the outside world know where she lives:

“Worldly wise in hard and poor necessities, she was innocent in all things else. Innocent, in the mist through which she saw her father, and the prison, and the turbid living river that flowed through it and flowed on.”

By the end of the chapter we know that Amy is usually called “Little Dorrit”, as that is the name of the family headed by “The Father of the Marshalsea”; a family whose history we have just learned.

We now concentrate our attention on the baby, “The Child of the Marshalsea”. She has been “handed down among the generations of collegians”, and the turnkey is her godfather.

The Child of the Marshalsea soon learns that although she and her brother and sister may venture out, her father can not. Wistful and wondering:

“With a pitiful and plaintive look for everything, indeed, but with something in it for only him that was like protection … With a pitiful and plaintive look for her wayward sister; for her idle brother; for the high blank walls; for the faded crowd they shut in; for the games of the prison children as they whooped and ran, and played at hide-and-seek, and made the iron bars of the inner gateway ‘Home.’”

The Child of the Marshalsea and the Turnkey - Arthur A. Dixon 1905

She reaches the age of eight. The turnkey is like another father to her, taking her out on little expeditions to the country, so that she can see the world outside, and experience grass, trees and flowers. The turnkey wants to leave his money to this Child of the Marshalsea, but although he had been advised to settle it “strictly on herself” nobody could tell him how it could remain secure in her hands, if she had wanted to give it away, so he dies intestate, when she is sixteen.

But the narrator tells us that long before that, the Father of the Marshalsea had come to rely on her quiet strength, as she sat beside him:

“she drudged on, until recognised as useful, even indispensable … She took the place of eldest of the three, in all things but precedence; was the head of the fallen family; and bore, in her own heart, its anxieties and shames.”

It is the Child of the Marshalsea who takes care of them all. She begins to do the family accounts at thirteen, and looks for opportunities for her family within the prison. She always prefaces her appeals with:

“‘If you please, I was born here, sir.” and nobody can resist. She asks a new prisoner, who is a dancing instructor, to give her older sister lessons. He is happy to do this, and her sister learns quickly, well enough to become a dancer. She also asks a seamstress to teach her how to do needlework, and soon becomes adept at this.

The two sisters are now able to go out and earn a little money, although they have to keep it secret from their father, who is keeping up the fiction of gentility, and would be mortified if he knew they worked for a living. The older sister also goes to live with her uncle, to facilitate this:

“He had been a very indifferent musical amateur in his better days; and when he fell with his brother, resorted for support to playing a clarionet as dirty as himself in a small Theatre Orchestra. It was the theatre in which his niece became a dancer;”

The challenge comes with her brother. The Child of the Marshalsea arranges many jobs for him, but he tires of them all, and always ends up “cutting” just about everything. She even pinches and scrapes enough together to pay for a passage to Canada. But he gets no further than Liverpool, and never gets on the ship. He arrives back at the Marshalsea “in rags, without shoes, and much more tired than ever.”

What’s more, although her brother claims to have started a new job, he is soon in the Marshalsea on his own account—as a prisoner. The Child of the Marshalsea, whom we now know is called “Amy”, begs him not to tell the truth to their father, because she thinks the knowledge would kill him. So the fiction is kept up by all:

“the collegians, with a better comprehension of the pious fraud than Tip, supported it loyally.”

We learn that “Tip” is Amy’s older brother, Edward. He was called Teddy when younger, and then eventually “Tip”. Her older sister is called ”Fanny”.

Amy herself, never lets anyone in the outside world know where she lives:

“Worldly wise in hard and poor necessities, she was innocent in all things else. Innocent, in the mist through which she saw her father, and the prison, and the turbid living river that flowed through it and flowed on.”

By the end of the chapter we know that Amy is usually called “Little Dorrit”, as that is the name of the family headed by “The Father of the Marshalsea”; a family whose history we have just learned.

It’s noticeable that in chapters 6 and 7, Dickens has been switching between times, rather than sticking to chronological order. It makes it far more interesting, and feels as if someone is telling us their memories. That might be why it has such a disjoined feel too, as Elizabeth noticed, with even longer sentences and much use of punctuation to break it up. To me it feels like proto-“stream of consciousness” writing.

Mr. Dorrit seems rather vain and self-centred, acting as if he does not notice where the money his daughters earn comes from. In the previous chapter 6, Amy’s father had begun to enjoy his position as “Father of the Marshalsea” until one day when a plasterer puts a little pile of halfpence in his hand. He then keenly feels the ignominy of accepting copper coins, and saying: “How dare you!” he feebly bursts into tears. The plasterer assures him that he meant well, and respects Mr. Dorrit, and they part on good terms. However, the prisoners notice that he seems changed: “he walked so late in the shadows of the yard, and seemed so downcast.”

Plornish the plasterer—it’s interesting that he has this little cameo role. I wonder if he is going to become centre stage at any point.

Mr. Dorrit seems rather vain and self-centred, acting as if he does not notice where the money his daughters earn comes from. In the previous chapter 6, Amy’s father had begun to enjoy his position as “Father of the Marshalsea” until one day when a plasterer puts a little pile of halfpence in his hand. He then keenly feels the ignominy of accepting copper coins, and saying: “How dare you!” he feebly bursts into tears. The plasterer assures him that he meant well, and respects Mr. Dorrit, and they part on good terms. However, the prisoners notice that he seems changed: “he walked so late in the shadows of the yard, and seemed so downcast.”

Plornish the plasterer—it’s interesting that he has this little cameo role. I wonder if he is going to become centre stage at any point.

I was unable to comment on yesterday's chapter and have nothing really to add to what has already been said. I find these two chapters very interesting and useful in giving us a full picture of who all the members of this family are and how Amy figures into both the family and the prison dynamic.

I was unable to comment on yesterday's chapter and have nothing really to add to what has already been said. I find these two chapters very interesting and useful in giving us a full picture of who all the members of this family are and how Amy figures into both the family and the prison dynamic.This is prison in such a different guise than anything we know of today. It is incomprehensible that when a man was thrown into prison, his family literally came to live with him and that Amy was born in the prison and completely raised there. The sweetness of her disposition is easy to see in the attachment that is formed between her and the turnkey, who is a confirmed bachelor and not particularly fond of children in general. It is sad that he is unable to leave her the money, but it is clear to me that it would have been futile in any case, since she would surely have turned it over to her father and seen it do little for herself.

All her efforts for her brother are in vain and he ends up just like the father, imprisoned for debt. I feel a sympathy for him, because he has been raised in this way and prison life is what he knows and understands...the place he feels comfortable and capable. However, I also feel angry with him because he has turned away numerous opportunities to turn his life in a different direction and has wasted them. That surely makes him less deserving of all the care and worry his little sister has taken on his behalf. I'm guessing those kinds of opportunities for children in his situation were few and far between.

She goes to great lengths to disguise her going into the prison, but Arthur now knows her secret and what will he do with that information? In fact, what does he think of it?

message 342:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 21, 2020 09:48AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Sara wrote: "All her efforts for her brother are in vain and he ends up just like the father, imprisoned for debt ..."

Sara - you said (very nicely!) earlier that I see the best in everybody, but I can find little to commend so far in Tip :( Except the fact that he listens to Amy! Otherwise he seems to have no staying power, is lazy and out for easy money.

Yes, we can give both Tip and Fanny some leeway, as they have known the world outside before their father's incarceration, but how much more deserving is Amy, who has used so much initiative in finding opportunities from them, rather than for herself. She seems truly devoted to her family, and especially her father. As you point out Sara "she goes to great lengths to disguise her going into the prison", and yet I don't feel at all that she is personally ashamed of her father, but only that she realises others would think it something to be ashamed of.

Amy seems so resourceful and intelligent, that I do wonder what her mother was like! Or perhaps this could be her father's genes; it's just that he uses his intelligence and perception in another direction.

On the whole, I think Amy has learnt a lot from the turnkey. He gave her worthwhile early life experiences, by taking her under his wing, and showing her as much of the world as he could. Perhaps he instilled her moral values too.

"Arthur now knows her secret and what will he do with that information?" Good question. We have one more chapter in this second installment, and we all know how much Charles Dickens loves to leave us on a cliff-hanger. The action of chapters 6 and 7 follows on, so perhaps that is where we will go next. Or perhaps he'll go off at a tangent with new characters!

Sara - you said (very nicely!) earlier that I see the best in everybody, but I can find little to commend so far in Tip :( Except the fact that he listens to Amy! Otherwise he seems to have no staying power, is lazy and out for easy money.

Yes, we can give both Tip and Fanny some leeway, as they have known the world outside before their father's incarceration, but how much more deserving is Amy, who has used so much initiative in finding opportunities from them, rather than for herself. She seems truly devoted to her family, and especially her father. As you point out Sara "she goes to great lengths to disguise her going into the prison", and yet I don't feel at all that she is personally ashamed of her father, but only that she realises others would think it something to be ashamed of.

Amy seems so resourceful and intelligent, that I do wonder what her mother was like! Or perhaps this could be her father's genes; it's just that he uses his intelligence and perception in another direction.

On the whole, I think Amy has learnt a lot from the turnkey. He gave her worthwhile early life experiences, by taking her under his wing, and showing her as much of the world as he could. Perhaps he instilled her moral values too.

"Arthur now knows her secret and what will he do with that information?" Good question. We have one more chapter in this second installment, and we all know how much Charles Dickens loves to leave us on a cliff-hanger. The action of chapters 6 and 7 follows on, so perhaps that is where we will go next. Or perhaps he'll go off at a tangent with new characters!

A sad and sweet chapter.

A sad and sweet chapter.The sad: "There was no instruction for any of them at home; but she knew well—no one better—that a man so broken as to be the Father of the Marshalsea, could be no father to his own children."

The sweet: The turnkey taking Little Dorrit out to gather grass and flowers.

Sara wrote: "I feel a sympathy for him, because he has been raised in this way and prison life is what he knows and understands...the place he feels comfortable and capable. However, I also feel angry with him because he has turned away numerous opportunities to turn his life in a different direction and has wasted them. "

Sara wrote: "I feel a sympathy for him, because he has been raised in this way and prison life is what he knows and understands...the place he feels comfortable and capable. However, I also feel angry with him because he has turned away numerous opportunities to turn his life in a different direction and has wasted them. "Sara, I have the same feelings towards Tip, sympathy and anger.

I like the way Dickens describes him, as if he was a prisoner in the soul: ”this foredoomed Tip appeared to take the prison wall with him”. We all bring our family home with us when we go away and start our own life. What if our family home was a prison, full of listless downcast people. Some of them manage to pay their debt and get out, but most of them “slip into a smooth descent”, like the doctor, or Tip’s father, and a father is the first male model to imitate for a son.

On the other hand I can't completely escuse his behaviour.

Bionic Jean wrote: "I don't feel at all that she is personally ashamed of her father, but only that she realises others would think it something to be ashamed of."

Bionic Jean wrote: "I don't feel at all that she is personally ashamed of her father, but only that she realises others would think it something to be ashamed of."Jean, you are right. I thought Amy’s feelings towards her father were conflicted feelings between pride and shame, but your analysis is more subtle.

Debra wrote: "The sweet: The turnkey taking Little Dorrit out to gather grass and flowers."

Debra wrote: "The sweet: The turnkey taking Little Dorrit out to gather grass and flowers."Oh yes Debra, a bitter-sweet chapter.

The relationship between Amy and the turnkey is sweet. The little sleeping child of the Marshalsea, covered by the turnkey with his pocket handkerchief, reminds me of Thumbelina with a rose-leaf for a counterpane, unless Victorian handkerchiefs were two meters wide. :)

Am outside, just finished reading Chapter VII, trying to enjoy the day in between bouts of bad air & heat. Today the air quality is not great but not horrible, so am enjoying a little time in my garden. I love this chapter, giving us a brief history of Amy, her daily life, her growing into being the mother of her little group. It is a very sweet & tender chapter. I smiled when I read the comment about the punctuation & complex sentences, after reading Faulkner in one of my honors seminars in college, especially Absalom, Absalom, Dickens seems not so bad. One sentence in A, A ran a 1 1/2 pages, was a Jeopardy answer back in the day. We are starting to have many of our players on our board, a few more are awaiting “fleshing our” or are lingering in the wings. Arthur’s curiosity will lead us on to more soon.

Am outside, just finished reading Chapter VII, trying to enjoy the day in between bouts of bad air & heat. Today the air quality is not great but not horrible, so am enjoying a little time in my garden. I love this chapter, giving us a brief history of Amy, her daily life, her growing into being the mother of her little group. It is a very sweet & tender chapter. I smiled when I read the comment about the punctuation & complex sentences, after reading Faulkner in one of my honors seminars in college, especially Absalom, Absalom, Dickens seems not so bad. One sentence in A, A ran a 1 1/2 pages, was a Jeopardy answer back in the day. We are starting to have many of our players on our board, a few more are awaiting “fleshing our” or are lingering in the wings. Arthur’s curiosity will lead us on to more soon.

.

..

Tip and prison.

I feel the same as Sara, "I feel a sympathy for him, because he has been raised in this way and prison life is what he knows and understands...the place he feels comfortable and capable."

Milena, your comment "...as if he was a prisoner in the soul: 'this foredoomed Tip appeared to take the prison wall with him'" made me think of this quote: "No matter where you go, there you are." -Buckaroo Banzai.

Amy and her father.

Jean, I think the same thing as you said, "I don't feel at all that she is personally ashamed of her father, but only that she realises others would think it something to be ashamed of."

Bionic Jean wrote: "It’s noticeable that in chapters 6 and 7, Dickens has been switching between times, rather than sticking to chronological order. It makes it far more interesting, and feels as if someone is telling..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "It’s noticeable that in chapters 6 and 7, Dickens has been switching between times, rather than sticking to chronological order. It makes it far more interesting, and feels as if someone is telling..."So far this book has reminded me of Bleak House in the way there are so many seemingly unconnected stories that Dickens keeps throwing our way in the beginning. I am looking forward to having all the threads sewn together.

Mr. Dorrit, or the Father of the Marshalsea, reminds me a lot of Mrs. Jellyby. Both are vain and self-centered, believing they are doing good in the world but oblivious to the sufferings around them. Both are neglecting their own children. Based on what you have said earlier about Mr. Dorrit mirroring Dickens' own father, I am guessing this is a theme in several of his novels?

Thank you for the wonderful reviews Jean!

Books mentioned in this topic

My Father As I Recall Him (other topics)Bleak House (other topics)

The Battle of Life (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...

Thank you, Jean for your explanations which I understand as Arthur's mother having a "whim" and treating Dorrit so well must have set off alarms in his head to the tune of something is going on here and it must be about the business which is all that she cares about.