Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit: Chapters 1 - 11

message 152:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 17, 2020 12:35PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Interestingly, the latest dramatisation of Little Dorrit cast the black actress Freema Agyeman as Tattycoram. Now although I would think she is Nigerian, I did wonder whether this was deliberate, rather than "colour blind" casting.

Freema Agyeman as "Tattycoram"

It put me in mind of Victorian heiresses from the West Indies as in Wide Sargasso Sea, who were very highly strung because of their upbringing and sudden exposure to the weather, lifestyle and rigid rules of behaviour they would be expected to follow in Victorian England.

Now I'm writing my own little back story here (!) but what if Tattycoram was an unwanted illegitimate daughter of someone like the heroine of Wide Sargasso Sea Antoinette Cosway, a Creole heiress, whose personality and experience plus (view spoiler) in Jane Eyre?

Please feel free to shoot this theory down in flames! Although I've noticed that quite a few illustrators did not show Tattycoram's face, so we can't see her ethnicity.

Freema Agyeman as "Tattycoram"

It put me in mind of Victorian heiresses from the West Indies as in Wide Sargasso Sea, who were very highly strung because of their upbringing and sudden exposure to the weather, lifestyle and rigid rules of behaviour they would be expected to follow in Victorian England.

Now I'm writing my own little back story here (!) but what if Tattycoram was an unwanted illegitimate daughter of someone like the heroine of Wide Sargasso Sea Antoinette Cosway, a Creole heiress, whose personality and experience plus (view spoiler) in Jane Eyre?

Please feel free to shoot this theory down in flames! Although I've noticed that quite a few illustrators did not show Tattycoram's face, so we can't see her ethnicity.

Luffy wrote: "Sara wrote: "Can you imagine adopting a child to make it a servant for yours?"

Luffy wrote: "Sara wrote: "Can you imagine adopting a child to make it a servant for yours?"It happened with Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors."

Well, I was thinking more in terms of how contemporary people would view it. Shakespeare is going back further than Dickens.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Interestingly, the latest dramatisation of Little Dorrit cast the black actress Freema Agyeman as Tattycoram. Now although I would think she is Nigerian, I did wonder whether this was ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Interestingly, the latest dramatisation of Little Dorrit cast the black actress Freema Agyeman as Tattycoram. Now although I would think she is Nigerian, I did wonder whether this was ..."Did Tattycoram's tantrum revealed to you that she was mental? Your back story can really be turned into a piece of fan fiction.

As an aside, there are lots of shades of Creoles around the world. In my country even. Our Creole women - and I know I've gone off topic - are the most beautiful ones here. Those especially who have a mixture of South Indian and African heritage are drop dead gorgeous.

Sara wrote: "Luffy wrote: "Sara wrote: "Can you imagine adopting a child to make it a servant for yours?"

Sara wrote: "Luffy wrote: "Sara wrote: "Can you imagine adopting a child to make it a servant for yours?"It happened with Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors."

Well, I was thinking more in terms ..."

Contemporary life is just as ugly as in the times of Shakespeare. Only they are not the norm. I assume everyone knows what kind of terror is being perpetuated right now. Even not counting uneven roles, e.g. employer/employee etc, lots of same status socialisation carry a potential to go medieval real fast. E.g. adopted kids, arranged marriage couples, caste system, muslim genocides etc.

Geez, Luffy, I was just saying you could not go into an adoption procedure and say "I want this kid for a servant for my own child", where that is exactly what happened here. The adoption procedures for a legal adoption are very tight now, as I have two friends who have adopted in the last few years and were vetted very thoroughly. I was merely commenting on the way things have changed since the 1880s...not suggesting our lives or our world is perfect.

Geez, Luffy, I was just saying you could not go into an adoption procedure and say "I want this kid for a servant for my own child", where that is exactly what happened here. The adoption procedures for a legal adoption are very tight now, as I have two friends who have adopted in the last few years and were vetted very thoroughly. I was merely commenting on the way things have changed since the 1880s...not suggesting our lives or our world is perfect.

Another heiress was the Caribbean one in Jane Austen's unfinished novel, Sanditon, who was played by a black actress in the recent PBS series.

Another heiress was the Caribbean one in Jane Austen's unfinished novel, Sanditon, who was played by a black actress in the recent PBS series.As far as the first 2 chapters being so unrelated, I wonder if Dickens was one of the first to do this? Many books, including some of Dickens are quite straightforward. It makes me think of how TV shows used to have 1 story with the same main characters, wrapped up in 30 or 60 minutes. Now they can feature multiple interlocking plots and spread out over a season or more. Dickens had diagrams of the plots of some of his books. He rarely if ever suffers from faults of "continuity" (a movie term) where things don't match up. On the other hand, Dumas, who wrote in a hurry for serial publication, and used assistants, had multiple instances where the story didn't match up or a secret is revealed to great fanfare, somehow ignoring that the same secret had been told earlier.

The contrasts of light and darkness are so striking in the descriptions of the dark jail, the bright light streaming in through the opened jail door, the staring sun of the oppressively hot port city of Marseilles with its residents seeking the shade and shadows for protection, and in chapter 2, the quarantined travelers seek to avoid the light as they walk "the bare scorched terrace" disappearing through "a staring white archway," and Meagles and the "grave dark man" turn "backward and forward in the shade of the wall" to escape the sun. The traditional definitions of whiteness and brightness being truth, and dark shadow being evil are reversed in that protection is obtained from shadows and from avoidance of the glaring sun. The brooding figure of Miss Wade sits in the shadows which provide protection for her but also signify something hidden or sinister. Thus we see Dickens using shadows to represent secrets, a hidden past, and perhaps corruption and a way to hide from the light and truth.

The contrasts of light and darkness are so striking in the descriptions of the dark jail, the bright light streaming in through the opened jail door, the staring sun of the oppressively hot port city of Marseilles with its residents seeking the shade and shadows for protection, and in chapter 2, the quarantined travelers seek to avoid the light as they walk "the bare scorched terrace" disappearing through "a staring white archway," and Meagles and the "grave dark man" turn "backward and forward in the shade of the wall" to escape the sun. The traditional definitions of whiteness and brightness being truth, and dark shadow being evil are reversed in that protection is obtained from shadows and from avoidance of the glaring sun. The brooding figure of Miss Wade sits in the shadows which provide protection for her but also signify something hidden or sinister. Thus we see Dickens using shadows to represent secrets, a hidden past, and perhaps corruption and a way to hide from the light and truth.

I think Tattycoram knew living with the Meagles was a way out for her. But that doesn't mean she had to like it. And it does seem that the Meagles were inconsiderate, maybe unknowingly.

I think Tattycoram knew living with the Meagles was a way out for her. But that doesn't mean she had to like it. And it does seem that the Meagles were inconsiderate, maybe unknowingly. A small story about my Aunt and Uncle. (Both teachers and both snobby.) They took in foreign students and expected those students to clean house and be a maid when they entertained, as well as other servant type duties. They thought this was perfectly reasonable. I was appalled! This was in the late 1900s.

message 160:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 16, 2020 03:19PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Luffy - I'm not sure of the critical points you are making.

"As an aside, there are lots of shades of Creoles around the world."

Exactly! This does not negate the point I was making at all. It is how casting directors manage to often cast actors from one country to portray someone from another. I know "Agyeman" to be a Nigerian name (from different friends I have had over the years), and therefore African. But Freema Agyeman was cast as Tattycoram - and earlier as an English companion to Doctor Who.

I also remember that Wide Sargasso Sea is set partly in Jamaica and partly in Dominica, (and yes, I have friends from both these places) which are both Caribbean islands. However, the novel was written in 1966, and at that time they were usually referred to as "the West Indies", and "Creole" was a convenient catch-all word. You may like or dislike these words, but I'm just using the terminology of the book.

"Did Tattycoram's tantrum revealed to you that she was mental?"

I'm also using the assumptions of the time. There were far fewer medical terms or diagnoses in Victorian times. There are novels by Charles Dickens which include a character who would then be classed as "insane", but he describes their behaviour so well that we can tell they are bi-polar, and/or manic depressive, or epileptic etc. Some of these conditions were known, and others weren't.

In addition to this, the Victorians believed that many conditions were hereditary. Therefore, if Tattycoram were the daughter of someone whose behaviour, without our modern drugs, was unbalanced, they may well believe that she would inherit this.

(Robin - Yes, thank you for mentioning that. These Caribbean heiresses did form a small part of English late 18th and 19th society.)

Luffy - Your post beginning "Contemporary life is just as ugly as in the times of Shakespeare ..."

has been answered by Sara. Please can get back to talking about the text? Everyone has made so many great points - and we could carry on discussing just one chapter for ages :)

But in a one chapter a day read, we really need to be focused, however important one may consider these other issues you mention, to be. And also, it helps if you can think partly as a Victorian writer/reader, and then bring your 21st century knowledge to bear on it.

"Your back story can really be turned into a piece of fan fiction."

I have no idea what this means either - except possibly it is disparaging. Mine was a theory, and one you may think is possible, or unlikely. I merely presented it as that.

We've ignored comments such as the one about Charles Dickens's IQ, but please could you try not to be quite so provocative? If these are genuine questions, then of course I'll try to answer you, but apart from anything else, it takes so much time! And it's only a few hours before we'll be posting about chapter 3.

Edit: On second thoughts, perhaps you are suggesting someone might like to use my idea to write another story - is that "fan fiction"? In which case, thank you, and feel free!

"As an aside, there are lots of shades of Creoles around the world."

Exactly! This does not negate the point I was making at all. It is how casting directors manage to often cast actors from one country to portray someone from another. I know "Agyeman" to be a Nigerian name (from different friends I have had over the years), and therefore African. But Freema Agyeman was cast as Tattycoram - and earlier as an English companion to Doctor Who.

I also remember that Wide Sargasso Sea is set partly in Jamaica and partly in Dominica, (and yes, I have friends from both these places) which are both Caribbean islands. However, the novel was written in 1966, and at that time they were usually referred to as "the West Indies", and "Creole" was a convenient catch-all word. You may like or dislike these words, but I'm just using the terminology of the book.

"Did Tattycoram's tantrum revealed to you that she was mental?"

I'm also using the assumptions of the time. There were far fewer medical terms or diagnoses in Victorian times. There are novels by Charles Dickens which include a character who would then be classed as "insane", but he describes their behaviour so well that we can tell they are bi-polar, and/or manic depressive, or epileptic etc. Some of these conditions were known, and others weren't.

In addition to this, the Victorians believed that many conditions were hereditary. Therefore, if Tattycoram were the daughter of someone whose behaviour, without our modern drugs, was unbalanced, they may well believe that she would inherit this.

(Robin - Yes, thank you for mentioning that. These Caribbean heiresses did form a small part of English late 18th and 19th society.)

Luffy - Your post beginning "Contemporary life is just as ugly as in the times of Shakespeare ..."

has been answered by Sara. Please can get back to talking about the text? Everyone has made so many great points - and we could carry on discussing just one chapter for ages :)

But in a one chapter a day read, we really need to be focused, however important one may consider these other issues you mention, to be. And also, it helps if you can think partly as a Victorian writer/reader, and then bring your 21st century knowledge to bear on it.

"Your back story can really be turned into a piece of fan fiction."

I have no idea what this means either - except possibly it is disparaging. Mine was a theory, and one you may think is possible, or unlikely. I merely presented it as that.

We've ignored comments such as the one about Charles Dickens's IQ, but please could you try not to be quite so provocative? If these are genuine questions, then of course I'll try to answer you, but apart from anything else, it takes so much time! And it's only a few hours before we'll be posting about chapter 3.

Edit: On second thoughts, perhaps you are suggesting someone might like to use my idea to write another story - is that "fan fiction"? In which case, thank you, and feel free!

A few more thoughts.

A few more thoughts. Like Petra, I thought of Rigaud when the strange moustachioed man appeared. But I cannot get it straight in my mind how much time has passed since we last saw Rigaud. And I had thought he was killed, but maybe not.

As for Miss. Wade. Jean asked "And did anyone get the impression she was goading Tattycoram, rather than calming her down?" Yes, that is what I thought. But, I could not tell if there was a sinister reason behind it, or if that was just Miss. Wade's personality.

Elizabeth, I like the observations too.

message 163:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 16, 2020 03:04PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Debra - that's why I really enjoy these discussions, because after I posted that about Miss Wade, some were thinking the same. But Pamela suggested that she was sizing her up, and Martha thought she was empathising, so I then thought yes, those are also possible interpretations! And I wouldn't have thought of them :)

As for the moustachioed man, perhaps we'll have to wait and see if his mouth goes up and his moustache comes down ;) But wasn't he on his way to be tried for murder, at the end of chapter 1?

As for the moustachioed man, perhaps we'll have to wait and see if his mouth goes up and his moustache comes down ;) But wasn't he on his way to be tried for murder, at the end of chapter 1?

Dickens seems to connect the first two chapters through the setting, the themes of light and dark, and imprisonment. Although we don't know Rigaud's fate after his leaving the jail, the characters in chapter 2 are also released from their quarantine jail. We know we are still in Marseilles as Chapter 2 opens with comments about "yesterday's howling over yonder" which I assumed to be the crowd's response to the appearance of Rigaud from the jail. Dickens commonly introduces new characters whose connections and relationships seem so disparate, but later reveals how they come together in the story. When Meagles says the travellers will each go their way and may never meet again, the reader can be sure to know that their lives will cross again.

Dickens seems to connect the first two chapters through the setting, the themes of light and dark, and imprisonment. Although we don't know Rigaud's fate after his leaving the jail, the characters in chapter 2 are also released from their quarantine jail. We know we are still in Marseilles as Chapter 2 opens with comments about "yesterday's howling over yonder" which I assumed to be the crowd's response to the appearance of Rigaud from the jail. Dickens commonly introduces new characters whose connections and relationships seem so disparate, but later reveals how they come together in the story. When Meagles says the travellers will each go their way and may never meet again, the reader can be sure to know that their lives will cross again. There seems to be belief in a sinister forewarning fatalism expressed by Miss Wade as well, that it is inevitable that certain people will meet and that what they do to you and you to them is preset and unavoidably will happen.

message 165:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 16, 2020 03:23PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Well spotted Elizabeth. Charles Dickens has suggested a few clues for us - or are they red herrings? We are not actually told what "yesterday's howling over yonder" refers to. (view spoiler). Time will tell.

Gee, what if "yesterday's howling over yonder" meant the other prisoner, the black mailer, was hung. While Rigaud was freed some time ago. This would kind of go along with Dickens protesting how things are.

Gee, what if "yesterday's howling over yonder" meant the other prisoner, the black mailer, was hung. While Rigaud was freed some time ago. This would kind of go along with Dickens protesting how things are.

I feel Miss Wade is taking stock of the servant girl Tattycoram when she passes by and finds the girl in a state of sheer distress. She appears surprised at Tattycoram's passionate display and thinks it "wonderful to see the fury of the contest in the girl" as if to say she is full of spirit after all even though subservient in the presence of the Meagles. Miss Wade expresses her concern and sorrow at seeing this distress and gives advice - "you must have patience"...and "must not mind it"... be more prudent - "you forget your dependent position." For someone who earlier is described as:

I feel Miss Wade is taking stock of the servant girl Tattycoram when she passes by and finds the girl in a state of sheer distress. She appears surprised at Tattycoram's passionate display and thinks it "wonderful to see the fury of the contest in the girl" as if to say she is full of spirit after all even though subservient in the presence of the Meagles. Miss Wade expresses her concern and sorrow at seeing this distress and gives advice - "you must have patience"...and "must not mind it"... be more prudent - "you forget your dependent position." For someone who earlier is described as: I am contained and self-reliant; your opinion is nothing

to me; I have no no interest in you, care nothing for you

and see and hear you with indifference."

- in this scene she seems to remove this mask to her feelings in her concern for Tattycoram.

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Dickens seems to connect the first two chapters through the setting, the themes of light and dark, and imprisonment. Although we don't know Rigaud's fate after his leaving the jail, the characters ..."

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Dickens seems to connect the first two chapters through the setting, the themes of light and dark, and imprisonment. Although we don't know Rigaud's fate after his leaving the jail, the characters ..."Well said, Elizabeth. That's my feeling about these chapters as well! The light and darkness as well as the feeling of impending doom. Also, I do want to say that every time I read this story I love and enjoy but also feel exasperated by Mr. Meagles! Such a sweet loving man and so clueless about so many things! Gah! OK, I feel better now. LOL

The other thing that strikes me about Chapter 2 is how everyone is shown in their own personal prisons of perspective, thoughts, and emotions. This is revealed as each character speaks about themselves; Mr. Meagles, Mr. Clennam, Miss Wade, and Tattycoram. Dickens is so good at showing the reader this.

Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignantly evil, just complacently self centered and oblivious. They appear not to have a clue how Tattycoram feels. Given the class divisions and ethnocentricity at the time, I don’t think they’re atypical. Many modern upper middle class people seem similarly oblivious to what those who have less endure. I would agree that the Meagles took on Tattycoram less out of caring for her and mostly to make themselves feel good. As “do gooders” often do. Mr. Meagle’s refusal to learn any language other than his own speaks to his notion of his own superiority over people of other countries. I also find the complaints about quarantine very relevant to our current pandemic. The Meagles could be alive now.

Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignantly evil, just complacently self centered and oblivious. They appear not to have a clue how Tattycoram feels. Given the class divisions and ethnocentricity at the time, I don’t think they’re atypical. Many modern upper middle class people seem similarly oblivious to what those who have less endure. I would agree that the Meagles took on Tattycoram less out of caring for her and mostly to make themselves feel good. As “do gooders” often do. Mr. Meagle’s refusal to learn any language other than his own speaks to his notion of his own superiority over people of other countries. I also find the complaints about quarantine very relevant to our current pandemic. The Meagles could be alive now.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well spotted Elizabeth. Charles Dickens has suggested a few clues for us - or are they red herrings? We are not actually told what "yesterday's howling over yonder" refers to. [spoi..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well spotted Elizabeth. Charles Dickens has suggested a few clues for us - or are they red herrings? We are not actually told what "yesterday's howling over yonder" refers to. [spoi..."No hindsight here, Jean - just speculation. Reading chapter by chapter with the group. Loving it - and I add my thanks for the chapter summaries you provide.

I wonder if perhaps Miss. Wade was a foundling as well, or maybe a poor relation and so sees herself in Tatty?

I wonder if perhaps Miss. Wade was a foundling as well, or maybe a poor relation and so sees herself in Tatty?

I also got the feeling that Miss Wade may have been in a similar position to Tatty. Tatty seems to be the only person she takes any interest in at all.

I also got the feeling that Miss Wade may have been in a similar position to Tatty. Tatty seems to be the only person she takes any interest in at all.

Mona wrote: "Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignan..."

Mona wrote: "Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignan..."I agree with your comments about the Meagles Mona. There are always people who get satisfaction from feeling like they are helping others when those they are helping might feel differently about it. I think Tatty's being adopted as a maid would probably have been better for her than being left in the foundling hospital. But it would have been difficult for her to always be treated as an inferior person while Pet was pampered by her parents.

I also think you have it right, Mona. The Meagles are good, but clueless, people. I think it would be a shock to them to think that anyone might not see their treatment of Tatty as perfectly kind and thoughtful.

I also think you have it right, Mona. The Meagles are good, but clueless, people. I think it would be a shock to them to think that anyone might not see their treatment of Tatty as perfectly kind and thoughtful.I will be interested in learning more about Miss Wade, because there is something underlying her attitudes, but I am not sure yet what it might be. She definitely resents others trying to do things "for her" and stresses her independence.

Calling it a night, and off to read Chapter Three for tomorrow. Night all.

Because of Mr. Meagles' strong aversion to the name Beadle, he changed Harriet Beadle's name which eventually became the diminishing Tattycoram. The word "beadle" was puzzling to me and I found it refers to a church officer who assists the minister.

Because of Mr. Meagles' strong aversion to the name Beadle, he changed Harriet Beadle's name which eventually became the diminishing Tattycoram. The word "beadle" was puzzling to me and I found it refers to a church officer who assists the minister.Meagles goes on a tirade that a beadle is an insolent person of authority (a Jack-in-office) not to be tolerated for their "absurdity," and a probable outmoded, useless anachronism. It is no wonder he discards the foundling homes's name and invents the "playful" name Tattycoram, even though, as Jean stated, it sounds like a name for a dog. Using the name of the home's founder, Coram, as part of her name forever links her to her past living experiences and a constant reminder of her abandonment - perhaps a bit of unconscious, unintended cruelty by the Meagles.

I don't remember reading about people in novels being quarantined. I did some checking, and, apparently countries were concerned about cholera, plague, and yellow fever. There was no international consistency among countries, at that time over any rules.

I don't remember reading about people in novels being quarantined. I did some checking, and, apparently countries were concerned about cholera, plague, and yellow fever. There was no international consistency among countries, at that time over any rules.

Elizabeth, great insight about the cruelty of Tattycoram’s name. Actually the poor woman seems to have very little choice about anything in her life. The “arbitrary” name of Harriet Beadle was assigned to her at the orphanage. The Meagles changed the name to Tattycoram (without asking her, apparently). No one ever seems to ask Tattycoram for her input about anything...her name, her role in life, etc. No wonder she is so conflicted about the Meagles. They did remove her from the Foundling Hospital, which was probably worse, but no one ever asks Tattycoram what she wants.

Elizabeth, great insight about the cruelty of Tattycoram’s name. Actually the poor woman seems to have very little choice about anything in her life. The “arbitrary” name of Harriet Beadle was assigned to her at the orphanage. The Meagles changed the name to Tattycoram (without asking her, apparently). No one ever seems to ask Tattycoram for her input about anything...her name, her role in life, etc. No wonder she is so conflicted about the Meagles. They did remove her from the Foundling Hospital, which was probably worse, but no one ever asks Tattycoram what she wants.

Kathleen, Mr. Meagles and the others mention the plague being the cause of the quarantine in France.

Kathleen, Mr. Meagles and the others mention the plague being the cause of the quarantine in France.

Sara wrote: "Geez, Luffy, I was just saying you could not go into an adoption procedure and say "I want this kid for a servant for my own child", where that is exactly what happened here. The adoption procedure..."

Sara wrote: "Geez, Luffy, I was just saying you could not go into an adoption procedure and say "I want this kid for a servant for my own child", where that is exactly what happened here. The adoption procedure..."My bad. I thought you were talking generally, and were championing a view too sanitized of the world.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy - I'm not sure of the critical points you are making.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy - I'm not sure of the critical points you are making. "As an aside, there are lots of shades of Creoles around the world."

Exactly! This does not negate the point I was making at all. It i..."

Sorry that I rubbed you the wrong way. As soon as I saw people going slightly off topic, I thought that was the norm. From now on I'll stick to the point. I was praising you with the fan fiction remark. It seems that I could do nothing right yesterday night. I'll try and remedy that.

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "The contrasts of light and darkness are so striking in the descriptions of the dark jail, the bright light streaming in through the opened jail door, the staring sun of the oppressively hot port ci..."

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "The contrasts of light and darkness are so striking in the descriptions of the dark jail, the bright light streaming in through the opened jail door, the staring sun of the oppressively hot port ci..."I think we cannot know what Dickens really wanted us to know, but your interpretations by themselves are ingenious. They remind me of the ecclesiastic explanations in other, holier, books.

Debra wrote: "Gee, what if "yesterday's howling over yonder" meant the other prisoner, the black mailer, was hung. While Rigaud was freed some time ago. This would kind of go along with Dickens protesting how th..."

Debra wrote: "Gee, what if "yesterday's howling over yonder" meant the other prisoner, the black mailer, was hung. While Rigaud was freed some time ago. This would kind of go along with Dickens protesting how th..."I don't think that happened, unless it did, lol! This book is turning out to be more than I expected. Unlike David Copperfield, the wrongdoers are very hard to pinpoint.

Mona wrote: "Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignan..."

Mona wrote: "Great comments again. I appreciate the summary, Jean, but I’ve “bitten the bullet” and started rereading the chapters in order to recall all the details. Btw, I don’t think the Meagles are malignan..."Don't cut them so much slack, Mona. They know exactly how Tattycoram feels. They all live together and have watched the servant grow up.

Jenny wrote: "I wonder if perhaps Miss. Wade was a foundling as well, or maybe a poor relation and so sees herself in Tatty?"

Jenny wrote: "I wonder if perhaps Miss. Wade was a foundling as well, or maybe a poor relation and so sees herself in Tatty?"Debra wrote: "Jenny, I was just wondering the same thing. I may have to rethink my opinion of Miss. Wade."

Katy wrote: "I also got the feeling that Miss Wade may have been in a similar position to Tatty. Tatty seems to be the only person she takes any interest in at all."

If Miss Wade is a good person, she, or rather the author, is hiding it really well.

Mona wrote: "Elizabeth, great insight about the cruelty of Tattycoram’s name. Actually the poor woman seems to have very little choice about anything in her life. The “arbitrary” name of Harriet Beadle was assi..."

Mona wrote: "Elizabeth, great insight about the cruelty of Tattycoram’s name. Actually the poor woman seems to have very little choice about anything in her life. The “arbitrary” name of Harriet Beadle was assi..."She is probably illiterate and has had no nanny, let alone a tutor. Her lot has barely improved by being with the Meagles. That's one of the reasons I believe the Meagles are evil.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy - I'm not sure of the critical points you are making.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy - I'm not sure of the critical points you are making. "As an aside, there are lots of shades of Creoles around the world."

Exactly! This does not negate the point I was making at all. It i..."

I'm sorry. When you mentioned the casting of such and such, I took it as an invitation to go slightly off topic. I know better now.

Kathleen wrote: "I don't remember reading about people in novels being quarantined. I did some checking, and, apparently countries were concerned about cholera, plague, and yellow fever. There was no international ..."

Kathleen wrote: "I don't remember reading about people in novels being quarantined. I did some checking, and, apparently countries were concerned about cholera, plague, and yellow fever. There was no international ..."Organisations, like the League of Nations, UNESCO, WHO, and doctors without borders didn't exist back then.

Bookworman wrote: "Well said, Elizabeth. That's my feeling about these chapters as well! The light and darkness as well as the feeling of impending doom. Also, I do want to say that every time I read this story I love and enjoy but also feel exasperated by Mr. Meagles! Such a sweet loving man and so clueless about so many things! Gah! OK, I feel better now. LOL

Bookworman wrote: "Well said, Elizabeth. That's my feeling about these chapters as well! The light and darkness as well as the feeling of impending doom. Also, I do want to say that every time I read this story I love and enjoy but also feel exasperated by Mr. Meagles! Such a sweet loving man and so clueless about so many things! Gah! OK, I feel better now. LOLThe other thing that strikes me about Chapter 2 is how everyone is shown in their own personal prisons of perspective, thoughts, and emotions. This is revealed as each character speaks about themselves; Mr. Meagles, Mr. Clennam, Miss Wade, and Tattycoram. Dickens is so good at showing the reader this."

I think Elizabeth is using structuralist techniques to dissect the chapters. I might do the same. I'll try at least. Dickens is very interpreting.

message 191:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 17, 2020 03:02AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

My goodness 20-odd comments "overnight" (for me). I'd love to reply to them all, but should move on to the next chapter (this doesn't stop anyone from commenting on previous ones though, of course). So just a few general points about:

Quarantine:

Yes it was because of the plague, and I put this in the first paragraph of my summary:

"The Meagles family are all returning from the East, and have had to spend some time in quarantine, as the plague is still rife there." (my words)

since Charles Dickens actually specified it.

Beadles and do-gooders:

Charles Dickens really disliked beadles, and all such functionaries. Remember the one in Oliver Twist? That was his first "proper" novel, in a way. Also the workhouse (via the beadle) gave the name to the foundling, Oliver Twist, fairly randomly, in an alphabetical sequence.

So it was the norm institutions, but Charles Dickens added an extra level of criticism, by then making Tattycoram's benefactors, the Meagles, change it again (as Elizabeth said) to a name which she would never be able to separate from her humble beginnings. There was nothing wrong with the name "Harriet"!

In this way. Charles Dickens was inserting himself in the book, although these parts seems like an omniscient narrator. He despised functionaries and institutions, (there's much more of that later!) and also disliked hypocritical do-gooders, who make it clear to everyone that this is what they are doing. One memorable portrait is of Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House, a woman with a missionary-like zeal for helping the poor in Africa, yet her own children and home were neglected as a result. She was based on a real person, but Charles Dickens peppers his novels with lots of these holier than thou do-gooders, as he considers they are hypocrites.

The Meagles' name is interesting. It is similar to both "beagle" and "meagre". Charles Dickens is not painting a portrait of them as outright bad people. In many ways they are simple, misguided, and blinkered, just as Miss Wade is many-layered. There have been some great points made about her!

By now, Charles Dickens was making his characters far more subtle. Yes, he'll include the odd villain to entertain us, but many are far more complex, and perhaps therefore more realistic.

I love how several here who have not read the novel, still jump ahead and surmise what will happen, or what someone is like. It just show what a master Charles Dickens is at controlling the tension and dropping just enough hints ...and it makes it such a pleasure to be reading it with you all :)

Mona - I'm delighted you're reading the actual text - again!!

Luffy - no worries, we're good! I know this group is different from your others, so it may take a while to find an appropriate, more focused way of commenting. But you've made some great contributions and are welcome! I'll message you.

Right, on to the next chapter.

Quarantine:

Yes it was because of the plague, and I put this in the first paragraph of my summary:

"The Meagles family are all returning from the East, and have had to spend some time in quarantine, as the plague is still rife there." (my words)

since Charles Dickens actually specified it.

Beadles and do-gooders:

Charles Dickens really disliked beadles, and all such functionaries. Remember the one in Oliver Twist? That was his first "proper" novel, in a way. Also the workhouse (via the beadle) gave the name to the foundling, Oliver Twist, fairly randomly, in an alphabetical sequence.

So it was the norm institutions, but Charles Dickens added an extra level of criticism, by then making Tattycoram's benefactors, the Meagles, change it again (as Elizabeth said) to a name which she would never be able to separate from her humble beginnings. There was nothing wrong with the name "Harriet"!

In this way. Charles Dickens was inserting himself in the book, although these parts seems like an omniscient narrator. He despised functionaries and institutions, (there's much more of that later!) and also disliked hypocritical do-gooders, who make it clear to everyone that this is what they are doing. One memorable portrait is of Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House, a woman with a missionary-like zeal for helping the poor in Africa, yet her own children and home were neglected as a result. She was based on a real person, but Charles Dickens peppers his novels with lots of these holier than thou do-gooders, as he considers they are hypocrites.

The Meagles' name is interesting. It is similar to both "beagle" and "meagre". Charles Dickens is not painting a portrait of them as outright bad people. In many ways they are simple, misguided, and blinkered, just as Miss Wade is many-layered. There have been some great points made about her!

By now, Charles Dickens was making his characters far more subtle. Yes, he'll include the odd villain to entertain us, but many are far more complex, and perhaps therefore more realistic.

I love how several here who have not read the novel, still jump ahead and surmise what will happen, or what someone is like. It just show what a master Charles Dickens is at controlling the tension and dropping just enough hints ...and it makes it such a pleasure to be reading it with you all :)

Mona - I'm delighted you're reading the actual text - again!!

Luffy - no worries, we're good! I know this group is different from your others, so it may take a while to find an appropriate, more focused way of commenting. But you've made some great contributions and are welcome! I'll message you.

Right, on to the next chapter.

message 192:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 17, 2020 02:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 3:

A dark, dismal and dreary chapter, which tells us all about Mr. Arthur Clennam’s early life. It begins:

“It was a Sunday evening in London, gloomy, close, and stale … Melancholy streets, in a penitential garb of soot, steeped the souls of the people who were condemned to look at them out of windows, in dire despondency”

and we have a long sardonic and depressing description of London, as it is seen through Arthur Clennam’s eyes. He has arrived in London, via Dover, Kent (where Aunt Betsey lived!) on a Sunday, and now sits in a coffee-house, and resenting the cacophonic bells.

“In every thoroughfare, up almost every alley, and down almost every turning, some doleful bell was throbbing, jerking, tolling, as if the Plague were in the city and the dead-carts were going round …

“How I have hated this day!”

Arthur muses over the Sundays on his past, and we see what a miserable childhood he had. Deprived of any love, or interest, he has lost any interest in life. He remembers his mother:

“stern of face and unrelenting of heart, would sit all day behind a Bible—bound, like her own construction of it, in the hardest, barest, and straitest boards—as if it, of all books! were a fortification against sweetness of temper, natural affection, and gentle intercourse.”

It is raining as he leaves the coffee-house, to make his way to his mother’s house, which he has not seen for 15 years:

“In the country, the rain would have developed a thousand fresh scents, and every drop would have had its bright association with some beautiful form of growth or life. In the city, it developed only foul stale smells, and was a sickly, lukewarm, dirt-stained, wretched addition to the gutters.”

He arrives to find “Nothing changed … Dark and miserable as ever …

It was a double house, with long, narrow, heavily-framed windows. Many years ago, it had had it in its mind to slide down sideways; it had been propped up, however, and was leaning on some half-dozen gigantic crutches: which gymnasium for the neighbouring cats, weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds, appeared in these latter days to be no very sure reliance.”

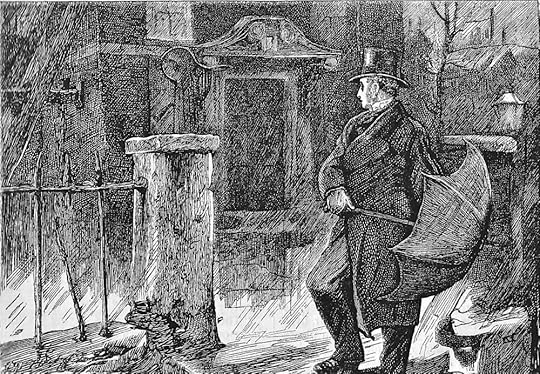

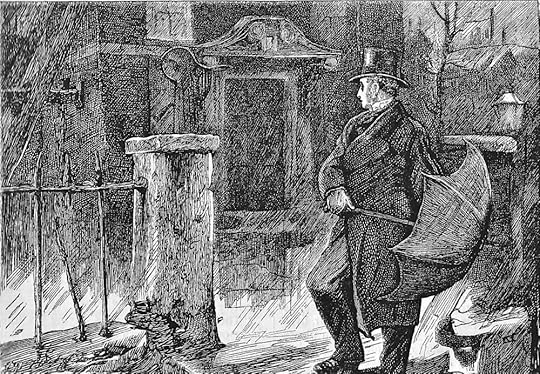

"Nothing Changed" by James Mahoney

The door is opened to him by Mr. Flintwinch, the old family servant and clerk, whose outward appearance oddly seems to mirror the lopsidedness of the house:

“His head was awry, and he had a one-sided, crab-like way with him, as if his foundations had yielded at about the same time as those of the house, and he ought to have been propped up in a similar manner.”

Mr. Flintwinch greets Arthur without much enthusiasm, and says he will inform Arthur’s mother that he has arrived. Everything in the house has remained exactly as it had been when he left.

Arthur feels just like a child again. All the memories of his gloomy childhood flood back. He remembers his father and mother, who would never exchange a friendly word with each other, but just sit there like two marble statues. And he spots the place he was regularly put in as a punishment:

“the old dark closet, also with nothing in it, of which he had been many a time the sole contents.”

Arthur is surprised to find that his mother is now sitting in a wheelchair, and she says she has been conducting the family business from the confines of her room. Mrs. Clennam seems as cold, proud and severe as Arthur remembers her:

“‘What with my rheumatic affection, and what with its attendant debility or nervous weakness—names are of no matter now—I have lost the use of my limbs. I never leave my room. I have not been outside this door for—tell him for how long,’ she said, speaking over her shoulder.

‘A dozen year next Christmas,’ returned a cracked voice out of the dimness behind.“

The voice belongs to Affery, another ancient servant: “a tall, hard-favoured, sinewy old woman”. Arthur remembers her, but since he left for the East, she has married Mr Jeremiah Flintwinch. Affery seems to have been bullied into this. As she tells Arthur later, she had no say in the matter; it had been decided between Mrs. Clennam and Mr. Flintwinch:

“Then stand up against them! She’s awful clever, and none but a clever one durst say a word to her. He’s a clever one—oh, he’s a clever one!—and he gives it her when he has a mind to’t, he does!”

On the table, Arthur recognises an old-fashioned gold watch, in a heavy double case. Just before his father had died, he had unaccountably—but most decidedly—asked Arthur to send it to his wife. Arthur had been puzzled:

“After my father’s death I opened it myself, thinking there might be, for anything I knew, some memorandum there. However, as I need not tell you, mother, there was nothing but the old silk watch-paper worked in beads, which you found (no doubt) in its place between the cases, where I found and left it.”

Mrs. Clennam says she keeps it by her, in remembrance of him. She then partakes of a frugal supper, which clearly is the same every evening. Arthur is sent away with Affery, who will make up a bed for him:

“They mounted up and up, through the musty smell of an old close house, little used, to a large garret bed-room. Meagre and spare, like all the other rooms, it was even uglier and grimmer than the rest, by being the place of banishment for the worn-out furniture.”

Affery confides in Arthur, and is his only friend in this dreary place. Arthur asks her about a girl he had seen in the gloom of his mother’s room. Affery refers to her as “Little Dorrit”, but shrugs her off, as “a whim” of her employer. She tells Arthur that a former sweetheart of his is now a wealthy widow. Also, that for some reason, the two ”clever ones had given her the impression that:

“if you like to have her, why you can.”

The chapter ends with Arthur remembering his youthful romantic thoughts, and dreaming of what his life might have been.

A dark, dismal and dreary chapter, which tells us all about Mr. Arthur Clennam’s early life. It begins:

“It was a Sunday evening in London, gloomy, close, and stale … Melancholy streets, in a penitential garb of soot, steeped the souls of the people who were condemned to look at them out of windows, in dire despondency”

and we have a long sardonic and depressing description of London, as it is seen through Arthur Clennam’s eyes. He has arrived in London, via Dover, Kent (where Aunt Betsey lived!) on a Sunday, and now sits in a coffee-house, and resenting the cacophonic bells.

“In every thoroughfare, up almost every alley, and down almost every turning, some doleful bell was throbbing, jerking, tolling, as if the Plague were in the city and the dead-carts were going round …

“How I have hated this day!”

Arthur muses over the Sundays on his past, and we see what a miserable childhood he had. Deprived of any love, or interest, he has lost any interest in life. He remembers his mother:

“stern of face and unrelenting of heart, would sit all day behind a Bible—bound, like her own construction of it, in the hardest, barest, and straitest boards—as if it, of all books! were a fortification against sweetness of temper, natural affection, and gentle intercourse.”

It is raining as he leaves the coffee-house, to make his way to his mother’s house, which he has not seen for 15 years:

“In the country, the rain would have developed a thousand fresh scents, and every drop would have had its bright association with some beautiful form of growth or life. In the city, it developed only foul stale smells, and was a sickly, lukewarm, dirt-stained, wretched addition to the gutters.”

He arrives to find “Nothing changed … Dark and miserable as ever …

It was a double house, with long, narrow, heavily-framed windows. Many years ago, it had had it in its mind to slide down sideways; it had been propped up, however, and was leaning on some half-dozen gigantic crutches: which gymnasium for the neighbouring cats, weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds, appeared in these latter days to be no very sure reliance.”

"Nothing Changed" by James Mahoney

The door is opened to him by Mr. Flintwinch, the old family servant and clerk, whose outward appearance oddly seems to mirror the lopsidedness of the house:

“His head was awry, and he had a one-sided, crab-like way with him, as if his foundations had yielded at about the same time as those of the house, and he ought to have been propped up in a similar manner.”

Mr. Flintwinch greets Arthur without much enthusiasm, and says he will inform Arthur’s mother that he has arrived. Everything in the house has remained exactly as it had been when he left.

Arthur feels just like a child again. All the memories of his gloomy childhood flood back. He remembers his father and mother, who would never exchange a friendly word with each other, but just sit there like two marble statues. And he spots the place he was regularly put in as a punishment:

“the old dark closet, also with nothing in it, of which he had been many a time the sole contents.”

Arthur is surprised to find that his mother is now sitting in a wheelchair, and she says she has been conducting the family business from the confines of her room. Mrs. Clennam seems as cold, proud and severe as Arthur remembers her:

“‘What with my rheumatic affection, and what with its attendant debility or nervous weakness—names are of no matter now—I have lost the use of my limbs. I never leave my room. I have not been outside this door for—tell him for how long,’ she said, speaking over her shoulder.

‘A dozen year next Christmas,’ returned a cracked voice out of the dimness behind.“

The voice belongs to Affery, another ancient servant: “a tall, hard-favoured, sinewy old woman”. Arthur remembers her, but since he left for the East, she has married Mr Jeremiah Flintwinch. Affery seems to have been bullied into this. As she tells Arthur later, she had no say in the matter; it had been decided between Mrs. Clennam and Mr. Flintwinch:

“Then stand up against them! She’s awful clever, and none but a clever one durst say a word to her. He’s a clever one—oh, he’s a clever one!—and he gives it her when he has a mind to’t, he does!”

On the table, Arthur recognises an old-fashioned gold watch, in a heavy double case. Just before his father had died, he had unaccountably—but most decidedly—asked Arthur to send it to his wife. Arthur had been puzzled:

“After my father’s death I opened it myself, thinking there might be, for anything I knew, some memorandum there. However, as I need not tell you, mother, there was nothing but the old silk watch-paper worked in beads, which you found (no doubt) in its place between the cases, where I found and left it.”

Mrs. Clennam says she keeps it by her, in remembrance of him. She then partakes of a frugal supper, which clearly is the same every evening. Arthur is sent away with Affery, who will make up a bed for him:

“They mounted up and up, through the musty smell of an old close house, little used, to a large garret bed-room. Meagre and spare, like all the other rooms, it was even uglier and grimmer than the rest, by being the place of banishment for the worn-out furniture.”

Affery confides in Arthur, and is his only friend in this dreary place. Arthur asks her about a girl he had seen in the gloom of his mother’s room. Affery refers to her as “Little Dorrit”, but shrugs her off, as “a whim” of her employer. She tells Arthur that a former sweetheart of his is now a wealthy widow. Also, that for some reason, the two ”clever ones had given her the impression that:

“if you like to have her, why you can.”

The chapter ends with Arthur remembering his youthful romantic thoughts, and dreaming of what his life might have been.

message 193:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 17, 2020 03:06AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Charles Dickens own religious views seem to colour this chapter. He was a Christian, but disliked Puritanism and any extreme or cheerless Christianity. Just think how he influenced the way Christmas is celebrated worldwide! Plus, his stories are full of Christian hypocrites, such as Mrs. Clennam, living so frugally, and clearly considering herself morally superior to everyone else, because they are able to leave their houses and interact with the world, and she chooses to live out some sort of penance.

Perhaps Arthur’s “prison” began with this:

“the dreary Sunday of his childhood, when he sat with his hands before him, scared out of his senses by a horrible tract which commenced business with the poor child by asking him in its title, why he was going to Perdition?”

Affery says that Little Dorrit is a “whim” of Mrs. Clennam’s. What an extraordinary thing to say of a person. Could something lie behind it? Is Affery privy to information, and perhaps more astute than she seems? She does give Arthur advice on how to deal with ”those two clever ones”.

I do love the quirky descriptions though, a couple of which I included. They add a bit of humour, which we need in this chapter! :)

Perhaps Arthur’s “prison” began with this:

“the dreary Sunday of his childhood, when he sat with his hands before him, scared out of his senses by a horrible tract which commenced business with the poor child by asking him in its title, why he was going to Perdition?”

Affery says that Little Dorrit is a “whim” of Mrs. Clennam’s. What an extraordinary thing to say of a person. Could something lie behind it? Is Affery privy to information, and perhaps more astute than she seems? She does give Arthur advice on how to deal with ”those two clever ones”.

I do love the quirky descriptions though, a couple of which I included. They add a bit of humour, which we need in this chapter! :)

message 194:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 17, 2020 02:53AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

A little more …

About how the writer G.K. Chesterton compared the characters of Arthur Clennam and David Copperfield.

compared the characters of Arthur Clennam and David Copperfield.

G.K. Chesterton much preferred the optimism of the novel David Copperfield, and we can see right from the start that the main character is an example of that positivity. Remember how David walked all the way from London to Dover, over several days, when he was still a child? Yet in the chapter we have just read, Arthur Clennam—a far older person—seems to feel he is not in charge of his life or destiny. He has almost given up on the world. This is how G.K. Chesterton puts it:

“David Copperfield and Arthur Clennam have both been brought up in unhappy homes, under bitter guardians and a black, disheartening religion. It is the whole point of David Copperfield that he has broken out of a Calvinistic tyranny which he cannot forgive. But it is the whole point of Arthur Clennam that he has not broken out of the Calvinistic tyranny, but is still under its shadow. Copperfield has come from a gloomy childhood; Clennam, though forty years old, is still in a gloomy childhood.”

He goes on to compare how the two behave, and this, again, is right at the start of the novel Little Dorrit, so there are no spoilers in that part:

“When David meets (view spoiler) But when Clennam re-enters his sepulchral house there is a weight upon his soul which makes it impossible for him to answer, with any spirit, the morbidities of his mother, or even the grotesque interferences of Mr. Flintwinch."

Even though we have only just started this novel the contrasts between these two characters is quite pronounced.

About how the writer G.K. Chesterton

compared the characters of Arthur Clennam and David Copperfield.

compared the characters of Arthur Clennam and David Copperfield. G.K. Chesterton much preferred the optimism of the novel David Copperfield, and we can see right from the start that the main character is an example of that positivity. Remember how David walked all the way from London to Dover, over several days, when he was still a child? Yet in the chapter we have just read, Arthur Clennam—a far older person—seems to feel he is not in charge of his life or destiny. He has almost given up on the world. This is how G.K. Chesterton puts it:

“David Copperfield and Arthur Clennam have both been brought up in unhappy homes, under bitter guardians and a black, disheartening religion. It is the whole point of David Copperfield that he has broken out of a Calvinistic tyranny which he cannot forgive. But it is the whole point of Arthur Clennam that he has not broken out of the Calvinistic tyranny, but is still under its shadow. Copperfield has come from a gloomy childhood; Clennam, though forty years old, is still in a gloomy childhood.”

He goes on to compare how the two behave, and this, again, is right at the start of the novel Little Dorrit, so there are no spoilers in that part:

“When David meets (view spoiler) But when Clennam re-enters his sepulchral house there is a weight upon his soul which makes it impossible for him to answer, with any spirit, the morbidities of his mother, or even the grotesque interferences of Mr. Flintwinch."

Even though we have only just started this novel the contrasts between these two characters is quite pronounced.

I read Little Dorrit's blurb before voting the pool (it didn't get my vote though.). But now I don't remember what was its theme (And I didn't read it again). So the first two chapters made me confused. I don't know how story will go on and I don't have any clue yet. Just with chapter 3 we met Little Dorrit :). I am really curious about how we will meet again the characters from chapter 1 and 2.

I read Little Dorrit's blurb before voting the pool (it didn't get my vote though.). But now I don't remember what was its theme (And I didn't read it again). So the first two chapters made me confused. I don't know how story will go on and I don't have any clue yet. Just with chapter 3 we met Little Dorrit :). I am really curious about how we will meet again the characters from chapter 1 and 2. Jean, Arthur Clennam, and David Copperfield's comparison really interesting. I would like to see Arthur being released from his exclusive prison soon. And thank you again for sharing this interesting informations and summaries. :)

Mr Meagles and his emphasis on practicality reminded me of Mr Gradgrind and his facts. At the moment, Mr Meagles seems to be a more sympathetic character than Mr Gradgrind was at the beginning of the respective books.

Mr Meagles and his emphasis on practicality reminded me of Mr Gradgrind and his facts. At the moment, Mr Meagles seems to be a more sympathetic character than Mr Gradgrind was at the beginning of the respective books.

Is it possible to have a separate thread for each chapter? It would make the comments much easier to navigate.

Is it possible to have a separate thread for each chapter? It would make the comments much easier to navigate.

Charles Dickens is so great at bringing atmospheres to life, and has such a knack for characters! I find myself hoping that Arthur will adopt Little Dorrit and bring both of them out of the gloom of his mothers home!

Charles Dickens is so great at bringing atmospheres to life, and has such a knack for characters! I find myself hoping that Arthur will adopt Little Dorrit and bring both of them out of the gloom of his mothers home!Jean, you have touched on one of my favorite characters from Oliver Twist!

I love how Dickens shows us Arthur Clennam's mood at the beginning of the chapter. Arthur sees London as dark, dirty, and ugly. The church bells bring back memories of a terrible childhood with strict punishments and no love. He almost takes a room at the tavern because he mentally dreads going to his mother's home. The description of the family home shows a neglected, dark place. And this is all before the tormented man goes into the house!

I love how Dickens shows us Arthur Clennam's mood at the beginning of the chapter. Arthur sees London as dark, dirty, and ugly. The church bells bring back memories of a terrible childhood with strict punishments and no love. He almost takes a room at the tavern because he mentally dreads going to his mother's home. The description of the family home shows a neglected, dark place. And this is all before the tormented man goes into the house!

Jean, the writing of Chesterton comparing the Murdstones with the Clennams is wonderful! I was thinking of Mr Murdstone when I was reading about Arthur's mother. They are such religious hypocrites treating children so terribly. They seem to enjoy wallowing in "fire and brimstone" quotes from the Bible, and ignoring the quotes about love and charity.

Jean, the writing of Chesterton comparing the Murdstones with the Clennams is wonderful! I was thinking of Mr Murdstone when I was reading about Arthur's mother. They are such religious hypocrites treating children so terribly. They seem to enjoy wallowing in "fire and brimstone" quotes from the Bible, and ignoring the quotes about love and charity.

Books mentioned in this topic

My Father As I Recall Him (other topics)Bleak House (other topics)

The Battle of Life (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...

They do indeed! You put this so well and several have mentioned this point. Our 21st century view is that no child should be taken to be a servant, but even Charles Dickens's contemporary readers may have been able to spot how blinkered they were, to anything outside their own comforts.

However, as France Andree says:

"The thing is though becoming a servant, wasn't it the aim of the place she was in?"

Yes, I think Thomas Coram would have viewed her placement with the Meagles as a success.

"Or maybe, the foundling place did not have the same aim as the Workhouse in the end?"

It would have been a more benevolent and kindly institution than the dreaded Workhouse. But if the Meagles believed that they had done a good and charitable thing, according to the attitudes of the time, should they have been quite so impervious to Tattycoram's unhappiness? (Sara and Robin have both made this point.) Their behaviour show how self-centred they are, as Tattycoram's outbursts are clearly a regular event.

Also, and I think this is most significant, after her outburst with Miss Wade, she said how kind the Meagles were, and how lucky she was.