The Old Curiosity Club discussion

David Copperfield

>

DC Chp. 22-24

Kim wrote: "Steerforth reminds me of my sister (kind of), he can talk to anyone, he does talk to anyone, they all love him, then when they turn away he says nasty things about them. My sister talks to everybod..."

I know one or two people like that, Kim, who simply can get on well with everyone, on the surface, and later don't mince their words. I am not exactly remiss as regards the not mincing of my words, as people who know me would readily confirm, but I somehow have never learned the trick of not showing my dislike to a person I dislike. My wife thinks it very undiplomatic in me, but I couldn't for the life of me actively engage in a pleasant conversation with someone unless I liked them. In consequence, people can be very sure that I won't backbite when I am friendly with them; by the same token, people to whom I am curt or rough may be sure that I won't mince words about them when their backs are turned. I might be a bit more diplomatic, but then you can't teach an old dog like me new tricks.

I know one or two people like that, Kim, who simply can get on well with everyone, on the surface, and later don't mince their words. I am not exactly remiss as regards the not mincing of my words, as people who know me would readily confirm, but I somehow have never learned the trick of not showing my dislike to a person I dislike. My wife thinks it very undiplomatic in me, but I couldn't for the life of me actively engage in a pleasant conversation with someone unless I liked them. In consequence, people can be very sure that I won't backbite when I am friendly with them; by the same token, people to whom I am curt or rough may be sure that I won't mince words about them when their backs are turned. I might be a bit more diplomatic, but then you can't teach an old dog like me new tricks.

Kim wrote: "There was a real life Miss Mowcher. Dickens supposedly based the character of Miss Mowcher on Mrs. Jane Seymour Hill, Dickens' wife Catherine's chiropodist. Mrs. Seymour Hill recognized herself as ..."

It was surely very infelicitous of Dickens to use a real-life example in order to base a character like Miss Mowcher on them because it would surely be noticed by the person in question and cause pain, and one should think that a person with physical deformities might have enough pain already. That was quite insensitive of Dickens, and I am interested in seeing how Miss Mowcher will be changed in the course of the novel. I found that Miss Mowcher's playful tone and her tendency to poke fun at herself might be a way of dealing with the true pain she might be feeling, and so I didn't regard her in as negative a light as Dickens's contemporaries were regarding her. To me, Miss Mowcher looked like a caricature at first sight only and like a deeply wounded person behind the mask of levity.

It was surely very infelicitous of Dickens to use a real-life example in order to base a character like Miss Mowcher on them because it would surely be noticed by the person in question and cause pain, and one should think that a person with physical deformities might have enough pain already. That was quite insensitive of Dickens, and I am interested in seeing how Miss Mowcher will be changed in the course of the novel. I found that Miss Mowcher's playful tone and her tendency to poke fun at herself might be a way of dealing with the true pain she might be feeling, and so I didn't regard her in as negative a light as Dickens's contemporaries were regarding her. To me, Miss Mowcher looked like a caricature at first sight only and like a deeply wounded person behind the mask of levity.

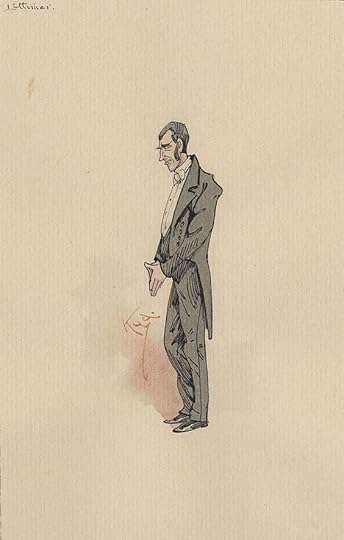

Kim wrote: "That last illustration looks nothing like Steerforth, at least not the one in my mind."

Absolutely; that's not at all a Steerforth people would be fascinated with.

Absolutely; that's not at all a Steerforth people would be fascinated with.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "When Steerforth is describing to David what a proctor is, this was cut from the original manuscript:

"I confess I think it's in the main a question of gammon and spinach, as my friend ..."

I guess that Dickens was trimming here, even though there is a strong sense of foreboding in these words by Steerforth, but then I think that Dickens never shunned foreboding but rather enjoyed it.

"I confess I think it's in the main a question of gammon and spinach, as my friend ..."

I guess that Dickens was trimming here, even though there is a strong sense of foreboding in these words by Steerforth, but then I think that Dickens never shunned foreboding but rather enjoyed it.

Tristram wrote: "Miss Mowcher's playful tone and her tendency to poke fun at herself might be a way of dealing with the true pain she might be feeling"

You are right there. I don't know about Miss Mowcher, but I've made fun of my seizures for most of my life, well I started getting them when I was eight and I'm now fifty eight so I consider that most of my life. I can find all sorts of amusing things to say about them and my headaches, but when people make fun of them, not necessarily mine, but someone else's I see red. The red I see may be spinning around like things are right now, but I'm mad. See, now was that a way of saying something poking fun at myself? Usually every day shortly after I take my pills the room starts spinning around. I've never been able to control this unless I just don't take them. I haven't yet figured it out, take them before eating, after eating, before exercise, after, it doesn't matter, but I don't really care anyway. I've often wished it was at night though, that way I could put colored lightbulbs in all the lights and watch them spin around, but I've never tried it yet. After all these years the dizziness will probably stay right where it is. And I'm fine with it all, if I woke up without a headache I'd be afraid I was dead. But on hearing that someone kept complaining about her migraines and she should stop because it was only a headache, the person dumb enough to be telling me this is lucky she walked away without me telling her what I really thought of her. To this day I avoid her and she wonders why. When our president thought it was a good idea to go on television and make fun of someone with a condition that made them shake and looked to me like he was making fun of someone having a seizure, it didn't matter what condition he was making fun of, it doesn't matter who he is, if I saw him I would walk away. OK, sorry for all that, I feel like I'm rambling, and I did think it was insensitive of Dickens unless as he said, he wasn't thinking of her. I have my doubts though.

You are right there. I don't know about Miss Mowcher, but I've made fun of my seizures for most of my life, well I started getting them when I was eight and I'm now fifty eight so I consider that most of my life. I can find all sorts of amusing things to say about them and my headaches, but when people make fun of them, not necessarily mine, but someone else's I see red. The red I see may be spinning around like things are right now, but I'm mad. See, now was that a way of saying something poking fun at myself? Usually every day shortly after I take my pills the room starts spinning around. I've never been able to control this unless I just don't take them. I haven't yet figured it out, take them before eating, after eating, before exercise, after, it doesn't matter, but I don't really care anyway. I've often wished it was at night though, that way I could put colored lightbulbs in all the lights and watch them spin around, but I've never tried it yet. After all these years the dizziness will probably stay right where it is. And I'm fine with it all, if I woke up without a headache I'd be afraid I was dead. But on hearing that someone kept complaining about her migraines and she should stop because it was only a headache, the person dumb enough to be telling me this is lucky she walked away without me telling her what I really thought of her. To this day I avoid her and she wonders why. When our president thought it was a good idea to go on television and make fun of someone with a condition that made them shake and looked to me like he was making fun of someone having a seizure, it didn't matter what condition he was making fun of, it doesn't matter who he is, if I saw him I would walk away. OK, sorry for all that, I feel like I'm rambling, and I did think it was insensitive of Dickens unless as he said, he wasn't thinking of her. I have my doubts though.

I agree that taking shots at someone's physical ailments is a low blow. Well see how Dickens goes forward with Miss Mowcher, but I'm afraid Tristram sees more depth to her than Dickens did, just as I did with Flora Finching. Funny (and sad) how an author can shortchange his own creations, while the reader can see so much more in them.

I agree that taking shots at someone's physical ailments is a low blow. Well see how Dickens goes forward with Miss Mowcher, but I'm afraid Tristram sees more depth to her than Dickens did, just as I did with Flora Finching. Funny (and sad) how an author can shortchange his own creations, while the reader can see so much more in them.

Kim wrote: "

Phiz in color. It seems like a stupid thing to say since it's obvious, but I want to let you know it is Phiz. I wonder if he colored it or if someone else came along and did later? I've never tri..."

Kim

To the best of my knowledge Browne never did the individual colourizations of a plate in any edition of any Dickens novel. He simply would not have had the time.

Out of interest (and as we are rapidly approaching Christmas) the only coloured plates that appear in Dickens original novels/novellas are the four that appear in A Christmas Carol. The illustrations in that novella were done by John Leech but the colourization of them was done by others. The process was very expensive and Dickens, as a businessman, realized it.

That said, if I may add a bit of bragging ... . As Kim shows us each week Hablot Browne made working drawings of the illustrations before the final version was etched and appeared in the novel. At times, Browne would put a “wash” on the early working version and sell it separately for additional income. One of the few indulgences in my life was to purchase an original working drawing that Browne did. It is from David Copperfield but we have not it got to it yet. If anyone would like to see it let me know.

Phiz in color. It seems like a stupid thing to say since it's obvious, but I want to let you know it is Phiz. I wonder if he colored it or if someone else came along and did later? I've never tri..."

Kim

To the best of my knowledge Browne never did the individual colourizations of a plate in any edition of any Dickens novel. He simply would not have had the time.

Out of interest (and as we are rapidly approaching Christmas) the only coloured plates that appear in Dickens original novels/novellas are the four that appear in A Christmas Carol. The illustrations in that novella were done by John Leech but the colourization of them was done by others. The process was very expensive and Dickens, as a businessman, realized it.

That said, if I may add a bit of bragging ... . As Kim shows us each week Hablot Browne made working drawings of the illustrations before the final version was etched and appeared in the novel. At times, Browne would put a “wash” on the early working version and sell it separately for additional income. One of the few indulgences in my life was to purchase an original working drawing that Browne did. It is from David Copperfield but we have not it got to it yet. If anyone would like to see it let me know.

Peter wrote: "If anyone would like to see it let me know..."

Peter wrote: "If anyone would like to see it let me know..."What a treasure to have! I would love to see it, but will try to be patient if you want to wait until the appropriate chapter to post it.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "If anyone would like to see it let me know..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "If anyone would like to see it let me know..."What a treasure to have! I would love to see it, but will try to be patient if you want to wait until the appropriate chapter to post it."

Yes, please!

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree that taking shots at someone's physical ailments is a low blow. Well see how Dickens goes forward with Miss Mowcher, but I'm afraid Tristram sees more depth to her than Dickens did, just as..."

This probably means that Dickens was better at writing than he thought, doesn't it? :-)

This probably means that Dickens was better at writing than he thought, doesn't it? :-)

Tristram wrote: "This probably means that Dickens was better at writing than he thought, doesn't it? :-)

Tristram wrote: "This probably means that Dickens was better at writing than he thought, doesn't it? :-)..."

Thinking about this might just make my head explode.

A review of David Copperfield:

Maia McAleavey, Assistant Professor of English, Boston College

“Of course I was in love with little Em’ly,” David Copperfield assures the reader of his childhood love. “I am sure I loved that baby quite as truly, quite as tenderly, with greater purity and more disinterestedness, than can enter into the best love of a later time of life.” Loving a person or a book (and “David Copperfield” conveniently appears to be both) may have nothing at all to do with bestness. The kind of judicious weighing that superlative requires lies quite apart from the easy way the reader falls in love with David Copperfield.

To my mind, David is far more loveable than Pip (Great Expectations’ fictional autobiographer), and better realized than Esther (Bleak House’s partial narrator). And it does help to have a first-person guide on Dickens’s exuberantly sprawling journeys. David, like Dickens, is a writer, and steers the reader through the novel as an unearthly blend of character, narrator, and author. This is not always a comforting effect. “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show,” David announces in his unsettling opening sentence.

Here he is, at once a young man thoroughly soused after a night of boozing and a comically estranging narrative voice: “Owing to some confusion in the dark, the door was gone. I was feeling for it in the window-curtains…We went down-stairs, one behind another. Near the bottom, somebody fell, and rolled down. Somebody else said it was Copperfield. I was angry at that false report, until, finding myself on my back in the passage, I began to think there might be some foundation for it.”

Is the novel nostalgic, sexist, and long? Yes, yes, and yes. But in its pages, Dickens also frames each of these qualities as problems. He meditates on the production, reproduction, and preservation of memories; he surrounds his typically perfect female characters, Dora and the Angel-in-the-House Agnes, with the indomitable matriarch Betsey Trotwood and the sexlessly maternal nurse Peggotty; and he lampoons the melodramatically longwinded Micawber while devising thousands of ways to keep the reader hooked. If you haven’t yet found your Dickensian first love, David’s your man.

Maia McAleavey, Assistant Professor of English, Boston College

“Of course I was in love with little Em’ly,” David Copperfield assures the reader of his childhood love. “I am sure I loved that baby quite as truly, quite as tenderly, with greater purity and more disinterestedness, than can enter into the best love of a later time of life.” Loving a person or a book (and “David Copperfield” conveniently appears to be both) may have nothing at all to do with bestness. The kind of judicious weighing that superlative requires lies quite apart from the easy way the reader falls in love with David Copperfield.

To my mind, David is far more loveable than Pip (Great Expectations’ fictional autobiographer), and better realized than Esther (Bleak House’s partial narrator). And it does help to have a first-person guide on Dickens’s exuberantly sprawling journeys. David, like Dickens, is a writer, and steers the reader through the novel as an unearthly blend of character, narrator, and author. This is not always a comforting effect. “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show,” David announces in his unsettling opening sentence.

Here he is, at once a young man thoroughly soused after a night of boozing and a comically estranging narrative voice: “Owing to some confusion in the dark, the door was gone. I was feeling for it in the window-curtains…We went down-stairs, one behind another. Near the bottom, somebody fell, and rolled down. Somebody else said it was Copperfield. I was angry at that false report, until, finding myself on my back in the passage, I began to think there might be some foundation for it.”

Is the novel nostalgic, sexist, and long? Yes, yes, and yes. But in its pages, Dickens also frames each of these qualities as problems. He meditates on the production, reproduction, and preservation of memories; he surrounds his typically perfect female characters, Dora and the Angel-in-the-House Agnes, with the indomitable matriarch Betsey Trotwood and the sexlessly maternal nurse Peggotty; and he lampoons the melodramatically longwinded Micawber while devising thousands of ways to keep the reader hooked. If you haven’t yet found your Dickensian first love, David’s your man.

Another one:

Leah Price, Professor of English, Harvard University

“Of all my books,” confessed Dickens in the preface, “I like this the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them. But, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is DAVID COPPERFIELD.”

David Copperfield fits the bill for a “best of” contest because it’s all about who’s first, who’s favorite, who’s primary. It’s one of Dickens’s few novels to be narrated entirely in the first person; it’s the only one whose narrator’s initials reverse Charles Dickens’s, and whose plot resembles the story that Dickens told friends about his own family and his own career. (But Dickens takes the novelist’s privilege of improving on the facts, notably by killing off David’s father before the novel opens in order to prevent him from racking up as many debts as Dickens senior did over the course of his inconveniently long life.)

That means that it’s also one of the few Dickens novels dominated by one character’s story and one character’s voice (This stands in contrast to Bleak House, say, which shuttles back and forth between two alternating narrators, one first-person and past-tense, the other third-person and couched in the present). As a result David Copperfield is less structurally complex, but also more concentrated, with an intensity of focus that can sometimes feel claustrophobic or monomaniacal but never loses its grip on a reader’s brain and heart. Its single-mindedness makes it more readable than a novel like Pickwick Papers, where the title character is little more than a human clothesline on which a welter of equally vivid minor characters are hung. Yet at the same time, it’s a novel about how hard it is to be first: Can you come first in your mother’s heart after she marries a wicked stepfather?

On David’s birthday, he tells us, “I went into the bar of a public-house, and said to the landlord: ‘What is your best — your very best — ale a glass?’ ‘Twopence-halfpenny,’ says the landlord, ‘is the price of the Genuine Stunning ale.'” David Copperfield is the genuine stunning: there’s nothing quite like it, in Dickens’s work or out.

Leah Price, Professor of English, Harvard University

“Of all my books,” confessed Dickens in the preface, “I like this the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them. But, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is DAVID COPPERFIELD.”

David Copperfield fits the bill for a “best of” contest because it’s all about who’s first, who’s favorite, who’s primary. It’s one of Dickens’s few novels to be narrated entirely in the first person; it’s the only one whose narrator’s initials reverse Charles Dickens’s, and whose plot resembles the story that Dickens told friends about his own family and his own career. (But Dickens takes the novelist’s privilege of improving on the facts, notably by killing off David’s father before the novel opens in order to prevent him from racking up as many debts as Dickens senior did over the course of his inconveniently long life.)

That means that it’s also one of the few Dickens novels dominated by one character’s story and one character’s voice (This stands in contrast to Bleak House, say, which shuttles back and forth between two alternating narrators, one first-person and past-tense, the other third-person and couched in the present). As a result David Copperfield is less structurally complex, but also more concentrated, with an intensity of focus that can sometimes feel claustrophobic or monomaniacal but never loses its grip on a reader’s brain and heart. Its single-mindedness makes it more readable than a novel like Pickwick Papers, where the title character is little more than a human clothesline on which a welter of equally vivid minor characters are hung. Yet at the same time, it’s a novel about how hard it is to be first: Can you come first in your mother’s heart after she marries a wicked stepfather?

On David’s birthday, he tells us, “I went into the bar of a public-house, and said to the landlord: ‘What is your best — your very best — ale a glass?’ ‘Twopence-halfpenny,’ says the landlord, ‘is the price of the Genuine Stunning ale.'” David Copperfield is the genuine stunning: there’s nothing quite like it, in Dickens’s work or out.

Kim wrote: "A review of David Copperfield:

Maia McAleavey, Assistant Professor of English, Boston College

“Of course I was in love with little Em’ly,” David Copperfield assures the reader of his childhood lo..."

An interesting review you found out there, Kim. The writer addresses Dickens's peculiar image of perfect womanhood but also has an eye for the more interesting female characters Dickens created. I just wonder that he didn't name Rosa Dartle in this context, because to me, she is even more fascinating than the indomitable Betsey Trotwood.

I don't know whether David is really more likeable than Pip, who may be a snob at times but finally comes to realize what he has done wrong with regard to Magwitch. I like Pip somewhat better because David remains very passive - even in situations where he could have prevented some evil, if he had just opened his eyes and plucked up his courage. He didn't see it coming that Steerforth would betray the Peggottys, and I think he could also have stepped in between Uriah and the Wickfields. But no, he mainly remains a chronicler.

Maia McAleavey, Assistant Professor of English, Boston College

“Of course I was in love with little Em’ly,” David Copperfield assures the reader of his childhood lo..."

An interesting review you found out there, Kim. The writer addresses Dickens's peculiar image of perfect womanhood but also has an eye for the more interesting female characters Dickens created. I just wonder that he didn't name Rosa Dartle in this context, because to me, she is even more fascinating than the indomitable Betsey Trotwood.

I don't know whether David is really more likeable than Pip, who may be a snob at times but finally comes to realize what he has done wrong with regard to Magwitch. I like Pip somewhat better because David remains very passive - even in situations where he could have prevented some evil, if he had just opened his eyes and plucked up his courage. He didn't see it coming that Steerforth would betray the Peggottys, and I think he could also have stepped in between Uriah and the Wickfields. But no, he mainly remains a chronicler.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

On these and other points, without forestalling what waits to be said of the composition of this fine story, a few illustrative words from his letters will properly find a place here. "Copperfield half done," he wrote of the second number on the 6th of June. "I feel, thank God, quite confident in the story. I have a move in it ready for this month; another for next; and another for the next." "I think it is necessary" (15th of November) "to decide against the special pleader. Your reasons quite suffice. I am not sure but that the banking house might do. I will consider it in a walk." "Banking business impracticable" (17th of November) "on account of the confinement: which would stop the story, I foresee. I have taken, for the present at all events, the proctor. I am wonderfully in harness, and nothing galls or frets." "Copperfield done" (20th of November) "after two days' very hard work indeed; and I think a smashing number. His first dissipation I hope will be found worthy of attention, as a piece of grotesque truth."

On these and other points, without forestalling what waits to be said of the composition of this fine story, a few illustrative words from his letters will properly find a place here. "Copperfield half done," he wrote of the second number on the 6th of June. "I feel, thank God, quite confident in the story. I have a move in it ready for this month; another for next; and another for the next." "I think it is necessary" (15th of November) "to decide against the special pleader. Your reasons quite suffice. I am not sure but that the banking house might do. I will consider it in a walk." "Banking business impracticable" (17th of November) "on account of the confinement: which would stop the story, I foresee. I have taken, for the present at all events, the proctor. I am wonderfully in harness, and nothing galls or frets." "Copperfield done" (20th of November) "after two days' very hard work indeed; and I think a smashing number. His first dissipation I hope will be found worthy of attention, as a piece of grotesque truth."

And again:

"I feel a great hope" (23rd of January, 1850) "that I shall be remembered by little Em'ly, a good many years to come." "I begin to have my doubts of being able to join you" (20th of February), "for Copperfield runs high, and must be done to-morrow. But I'll do it if possible, and strain every nerve. Some beautiful comic love, I hope, in the number."

"I feel a great hope" (23rd of January, 1850) "that I shall be remembered by little Em'ly, a good many years to come." "I begin to have my doubts of being able to join you" (20th of February), "for Copperfield runs high, and must be done to-morrow. But I'll do it if possible, and strain every nerve. Some beautiful comic love, I hope, in the number."

From The Letters of Charles Dickens:

Devonshire Terrace, July 13th, 1850.

My dear White,

Being obliged (sorely against my will) to leave my work this morning and go out, and having a few spare minutes before I go, I write a hasty note, to hint how glad I am to have received yours, and how happy and tranquil we feel it to be for you all, that the end of that long illness has come. Kate and Georgy send best loves to Mrs. White, and we hope she will take all needful rest and relief after those arduous, sad, and weary weeks. I have taken a house at Broadstairs, from early in August until the end of October, as I don't want to come back to London until I shall have finished "Copperfield." I am rejoiced at the idea of your going there. You will find it the healthiest and freshest of places; and there are Canterbury, and all varieties of what Leigh Hunt calls "greenery," within a few minutes' railroad ride. It is not very picturesque ashore, but extremely so seaward; all manner of ships continually passing close inshore. So come, and we'll have no end of sports, please God.

I am glad to say, as I know you will be to hear, that there seems a bright unanimity about "Copperfield." I am very much interested in it and pleased with it myself. I have carefully planned out the story, for some time past, to the end, and am making out my purposes with great care. I should like to know what you see from that tower of yours. I have little doubt you see the real objects in the prospect.

"Household Words" goes on thoroughly well. It is expensive, of course, and demands a large circulation; but it is taking a great and steady stand, and I have no doubt already yields a good round profit.

To-morrow week I shall expect you. You shall have a bottle of the "Twenty." I have kept a few last lingering caskets with the gem enshrined therein, expressly for you.

Ever, my dear White,

Cordially yours.

Devonshire Terrace, July 13th, 1850.

My dear White,

Being obliged (sorely against my will) to leave my work this morning and go out, and having a few spare minutes before I go, I write a hasty note, to hint how glad I am to have received yours, and how happy and tranquil we feel it to be for you all, that the end of that long illness has come. Kate and Georgy send best loves to Mrs. White, and we hope she will take all needful rest and relief after those arduous, sad, and weary weeks. I have taken a house at Broadstairs, from early in August until the end of October, as I don't want to come back to London until I shall have finished "Copperfield." I am rejoiced at the idea of your going there. You will find it the healthiest and freshest of places; and there are Canterbury, and all varieties of what Leigh Hunt calls "greenery," within a few minutes' railroad ride. It is not very picturesque ashore, but extremely so seaward; all manner of ships continually passing close inshore. So come, and we'll have no end of sports, please God.

I am glad to say, as I know you will be to hear, that there seems a bright unanimity about "Copperfield." I am very much interested in it and pleased with it myself. I have carefully planned out the story, for some time past, to the end, and am making out my purposes with great care. I should like to know what you see from that tower of yours. I have little doubt you see the real objects in the prospect.

"Household Words" goes on thoroughly well. It is expensive, of course, and demands a large circulation; but it is taking a great and steady stand, and I have no doubt already yields a good round profit.

To-morrow week I shall expect you. You shall have a bottle of the "Twenty." I have kept a few last lingering caskets with the gem enshrined therein, expressly for you.

Ever, my dear White,

Cordially yours.

I've been thinking, David has always had someone watching out for him. His mother, Peggotty, Steerforth, his aunt, now he's going to be alone in London looking out for himself. Is he ready for that?

From George Orwell's Charles Dickens:

No one, at any rate no English writer, has written better about childhood than Dickens. In spite of all the knowledge that has accumulated since, in spite of the fact that children are now comparatively sanely treated, no novelist has shown the same power of entering into the child's point of view. I must have been about nine years old when I first read David Copperfield. The mental atmosphere of the opening chapters was so immediately intelligible to me that I vaguely imagined they had been written by a child. And yet when one re-reads the book as an adult and sees the Murdstones, for instance, dwindle from gigantic figures of doom into semi-comic monsters, these passages lose nothing. Dickens has been able to stand both inside and outside the child's mind, in such a way that the same scene can be wild burlesque or sinister reality, according to the age at which one reads it. Look, for instance, at the scene in which David Copperfield is unjustly suspected of eating the mutton chops; or the scene in which Pip, in Great Expectations, coming back from Miss Havisham's house and finding himself completely unable to describe what he has seen, takes refuge in a series of outrageous lies — which, of course, are eagerly believed. All the isolation of childhood is there. And how accurately he has recorded the mechanisms of the child's mind, its visualizing tendency, its sensitiveness to certain kinds of impression. Pip relates how in his childhood his ideas about his dead parents were derived from their tombstones:

The shape of the letters on my father's, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, ‘ALSO GEORGIANA, WIFE OF THE ABOVE’, I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly. To five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine... I am indebted for a belief I religiously entertained that they had all been born on their backs with their hands in their trouser-pockets, and had never taken them out in this state of existence.

There is a similar passage in David Copperfield. After biting Mr. Murdstone's hand, David is sent away to school and obliged to wear on his back a placard saying, ‘Take care of him. He bites.’ He looks at the door in the playground where the boys have carved their names, and from the appearance of each name he seems to know in just what tone of voice the boy will read out the placard:

There was one boy — a certain J. Steerforth — who cut his name very deep and very often, who, I conceived, would read it in a rather strong voice, and afterwards pull my hair. There was another boy, one Tommy Traddles, who I dreaded would make game of it, and pretend to be dreadfully frightened of me. There was a third, George Demple, who I fancied would sing it.

When I read this passage as a child, it seemed to me that those were exactly the pictures that those particular names would call up. The reason, of course, is the sound-associations of the words Demple (‘temple’; Traddles — probably ‘skedaddle’). But how many people, before Dickens, had ever noticed such things? A sympathetic attitude towards children was a much rarer thing in Dickens's day than it is now. The early nineteenth century was not a good time to be a child. In Dickens's youth children were still being ‘solemnly tried at a criminal bar, where they were held up to be seen’, and it was not so long since boys of thirteen had been hanged for petty theft. The doctrine of ‘breaking the child's spirit’ was in full vigour, and The Fairchild Family was a standard book for children till late into the century. This evil book is now issued in pretty-pretty expurgated editions, but it is well worth reading in the original version. It gives one some idea of the lengths to which child-discipline was sometimes carried. Mr. Fairchild, for instance, when he catches his children quarrelling, first thrashes them, reciting Dr. Watts's ‘Let dogs delight to bark and bite’ between blows of the cane, and then takes them to spend the afternoon beneath a gibbet where the rotting corpse of a murderer is hanging. In the earlier part of the century scores of thousands of children, aged sometimes as young as six, were literally worked to death in the mines or cotton mills, and even at the fashionable public schools boys were flogged till they ran with blood for a mistake in their Latin verses. One thing which Dickens seems to have recognized, and which most of his contemporaries did not, is the sadistic sexual element in flogging. I think this can be inferred from David Copperfield and Nicholas Nickleby. But mental cruelty to a child infuriates him as much as physical, and though there is a fair number of exceptions, his schoolmasters are generally scoundrels.

No one, at any rate no English writer, has written better about childhood than Dickens. In spite of all the knowledge that has accumulated since, in spite of the fact that children are now comparatively sanely treated, no novelist has shown the same power of entering into the child's point of view. I must have been about nine years old when I first read David Copperfield. The mental atmosphere of the opening chapters was so immediately intelligible to me that I vaguely imagined they had been written by a child. And yet when one re-reads the book as an adult and sees the Murdstones, for instance, dwindle from gigantic figures of doom into semi-comic monsters, these passages lose nothing. Dickens has been able to stand both inside and outside the child's mind, in such a way that the same scene can be wild burlesque or sinister reality, according to the age at which one reads it. Look, for instance, at the scene in which David Copperfield is unjustly suspected of eating the mutton chops; or the scene in which Pip, in Great Expectations, coming back from Miss Havisham's house and finding himself completely unable to describe what he has seen, takes refuge in a series of outrageous lies — which, of course, are eagerly believed. All the isolation of childhood is there. And how accurately he has recorded the mechanisms of the child's mind, its visualizing tendency, its sensitiveness to certain kinds of impression. Pip relates how in his childhood his ideas about his dead parents were derived from their tombstones:

The shape of the letters on my father's, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, ‘ALSO GEORGIANA, WIFE OF THE ABOVE’, I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly. To five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine... I am indebted for a belief I religiously entertained that they had all been born on their backs with their hands in their trouser-pockets, and had never taken them out in this state of existence.

There is a similar passage in David Copperfield. After biting Mr. Murdstone's hand, David is sent away to school and obliged to wear on his back a placard saying, ‘Take care of him. He bites.’ He looks at the door in the playground where the boys have carved their names, and from the appearance of each name he seems to know in just what tone of voice the boy will read out the placard:

There was one boy — a certain J. Steerforth — who cut his name very deep and very often, who, I conceived, would read it in a rather strong voice, and afterwards pull my hair. There was another boy, one Tommy Traddles, who I dreaded would make game of it, and pretend to be dreadfully frightened of me. There was a third, George Demple, who I fancied would sing it.

When I read this passage as a child, it seemed to me that those were exactly the pictures that those particular names would call up. The reason, of course, is the sound-associations of the words Demple (‘temple’; Traddles — probably ‘skedaddle’). But how many people, before Dickens, had ever noticed such things? A sympathetic attitude towards children was a much rarer thing in Dickens's day than it is now. The early nineteenth century was not a good time to be a child. In Dickens's youth children were still being ‘solemnly tried at a criminal bar, where they were held up to be seen’, and it was not so long since boys of thirteen had been hanged for petty theft. The doctrine of ‘breaking the child's spirit’ was in full vigour, and The Fairchild Family was a standard book for children till late into the century. This evil book is now issued in pretty-pretty expurgated editions, but it is well worth reading in the original version. It gives one some idea of the lengths to which child-discipline was sometimes carried. Mr. Fairchild, for instance, when he catches his children quarrelling, first thrashes them, reciting Dr. Watts's ‘Let dogs delight to bark and bite’ between blows of the cane, and then takes them to spend the afternoon beneath a gibbet where the rotting corpse of a murderer is hanging. In the earlier part of the century scores of thousands of children, aged sometimes as young as six, were literally worked to death in the mines or cotton mills, and even at the fashionable public schools boys were flogged till they ran with blood for a mistake in their Latin verses. One thing which Dickens seems to have recognized, and which most of his contemporaries did not, is the sadistic sexual element in flogging. I think this can be inferred from David Copperfield and Nicholas Nickleby. But mental cruelty to a child infuriates him as much as physical, and though there is a fair number of exceptions, his schoolmasters are generally scoundrels.

More by Geeorge Orwell:

Except for the universities and the big public schools, every kind of education then existing in England gets a mauling at Dickens's hands. There is Doctor Blimber's Academy, where little boys are blown up with Greek until they burst, and the revolting charity schools of the period, which produced specimens like Noah Claypole and Uriah Heep, and Salem House, and Dotheboys Hall, and the disgraceful little dame-school kept by Mr. Wopsle's great-aunt. Some of what Dickens says remains true even today. Salem House is the ancestor of the modern ‘prep school’, which still has a good deal of resemblance to it; and as for Mr. Wopsle's great-aunt, some old fraud of much the same stamp is carrying on at this moment in nearly every small town in England. But, as usual, Dickens's criticism is neither creative nor destructive. He sees the idiocy of an educational system founded on the Greek lexicon and the wax-ended cane; on the other hand, he has no use for the new kind of school that is coming up in the fifties and sixties, the ‘modern’ school, with its gritty insistence on ‘facts’. What, then, does he want? As always, what he appears to want is a moralized version of the existing thing — the old type of school, but with no caning, no bullying or underfeeding, and not quite so much Greek. Doctor Strong's school, to which David Copperfield goes after he escapes from Murdstone & Grinby's, is simply Salem House with the vices left out and a good deal of ‘old grey stones’ atmosphere thrown in:

Doctor Strong's was an excellent school, as different from Mr. Creakle's as good is from evil. It was very gravely and decorously ordered, and on a sound system; with an appeal, in everything, to the honour and good faith of the boys... which worked wonders. We all felt that we had a part in the management of the place, and in sustaining its character and dignity. Hence, we soon became warmly attached to it — I am sure I did for one, and I never knew, in all my time, of any boy being otherwise — and learnt with a good will, desiring to do it credit. We had noble games out of hours, and plenty of liberty; but even then, as I remember, we were well spoken of in the town, and rarely did any disgrace, by our appearance or manner, to the reputation of Doctor Strong and Doctor Strong's boys.

In the woolly vagueness of this passage one can see Dickens's utter lack of any educational theory. He can imagine the moral atmosphere of a good school, but nothing further. The boys ‘learnt with a good will’, but what did they learn? No doubt it was Doctor Blimber's curriculum, a little watered down. Considering the attitude to society that is everywhere implied in Dickens's novels, it comes as rather a shock to learn that he sent his eldest son to Eton and sent all his children through the ordinary educational mill. Gissing seems to think that he may have done this because he was painfully conscious of being under-educated himself. Here perhaps Gissing is influenced by his own love of classical learning. Dickens had had little or no formal education, but he lost nothing by missing it, and on the whole he seems to have been aware of this. If he was unable to imagine a better school than Doctor Strong's, or, in real life, than Eton, it was probably due to an intellectual deficiency rather different from the one Gissing suggests.

Except for the universities and the big public schools, every kind of education then existing in England gets a mauling at Dickens's hands. There is Doctor Blimber's Academy, where little boys are blown up with Greek until they burst, and the revolting charity schools of the period, which produced specimens like Noah Claypole and Uriah Heep, and Salem House, and Dotheboys Hall, and the disgraceful little dame-school kept by Mr. Wopsle's great-aunt. Some of what Dickens says remains true even today. Salem House is the ancestor of the modern ‘prep school’, which still has a good deal of resemblance to it; and as for Mr. Wopsle's great-aunt, some old fraud of much the same stamp is carrying on at this moment in nearly every small town in England. But, as usual, Dickens's criticism is neither creative nor destructive. He sees the idiocy of an educational system founded on the Greek lexicon and the wax-ended cane; on the other hand, he has no use for the new kind of school that is coming up in the fifties and sixties, the ‘modern’ school, with its gritty insistence on ‘facts’. What, then, does he want? As always, what he appears to want is a moralized version of the existing thing — the old type of school, but with no caning, no bullying or underfeeding, and not quite so much Greek. Doctor Strong's school, to which David Copperfield goes after he escapes from Murdstone & Grinby's, is simply Salem House with the vices left out and a good deal of ‘old grey stones’ atmosphere thrown in:

Doctor Strong's was an excellent school, as different from Mr. Creakle's as good is from evil. It was very gravely and decorously ordered, and on a sound system; with an appeal, in everything, to the honour and good faith of the boys... which worked wonders. We all felt that we had a part in the management of the place, and in sustaining its character and dignity. Hence, we soon became warmly attached to it — I am sure I did for one, and I never knew, in all my time, of any boy being otherwise — and learnt with a good will, desiring to do it credit. We had noble games out of hours, and plenty of liberty; but even then, as I remember, we were well spoken of in the town, and rarely did any disgrace, by our appearance or manner, to the reputation of Doctor Strong and Doctor Strong's boys.

In the woolly vagueness of this passage one can see Dickens's utter lack of any educational theory. He can imagine the moral atmosphere of a good school, but nothing further. The boys ‘learnt with a good will’, but what did they learn? No doubt it was Doctor Blimber's curriculum, a little watered down. Considering the attitude to society that is everywhere implied in Dickens's novels, it comes as rather a shock to learn that he sent his eldest son to Eton and sent all his children through the ordinary educational mill. Gissing seems to think that he may have done this because he was painfully conscious of being under-educated himself. Here perhaps Gissing is influenced by his own love of classical learning. Dickens had had little or no formal education, but he lost nothing by missing it, and on the whole he seems to have been aware of this. If he was unable to imagine a better school than Doctor Strong's, or, in real life, than Eton, it was probably due to an intellectual deficiency rather different from the one Gissing suggests.

And as for what George Gissing said:

The year 1825, then, saw him at a day-school in North London: the ordinary day-school of that time, which is as much as to say that it was just better than no school at all. One cannot discover that he learnt anything there, or from any professed teacher elsewhere, beyond the very elements of common knowledge. And here again is a point on which throughout his life Dickens felt a certain soreness; he wished to be thought, wished to be, a well-educated man, yet was well aware that in several directions he could never make up for early defects of training. In those days it was socially more important than now to have received a "classical education", and with the classics he had no acquaintance. There is no mistaking the personal note in those passages of his books which treat of, or allude to, Greek and Latin studies in a satirical spirit. True, it is just as impossible to deny that, in this particular field of English life, every sort of insincerity was rampant. Carlyle (who, by the by, was no Grecian) threw scorn upon "gerund-grinding", and with justice; Dickens delighted in showing classical teachers as dreary humbugs, and in hinting that they were such by the mere necessity of the case. Mr. Feeder, B.A., grinds, with his Greek or Latin stop on, for the edification of Toots. Dr. Blimber snuffles at dinnertime, "It is remarkable that the Romans --", and every terrified boy assumes an air of impossible interest. Even Copperfield's worthy friend, Dr. Strong, potters in an imbecile fashion over a Greek lexicon which there is plainly not the slightest hope of his ever completing. Numerous are the side-hits at this educational idol of wealthy England. For all that, remember David's self-congratulation when, his school-days at an end, he feels that he is "well-taught"; in other words, that he is possessed of the results of Dr. Strong's mooning over dead languages. Dickens had far too much sense and honesty to proclaim a loud contempt where he knew himself ignorant. For an example of the sort of thing impossible to him, see the passage in an early volume of the Goncourts' Diary, where the egregious brothers report a quarrel with Saint-Victor, a defender of the Ancients; they, in their monumental fatuity, ending the debate by a declaration that a French novel called Adolphe was from every point of view preferable to Homer. Dickens knew better than this; but, having real ground for satire in the educational follies of the day, he indulged that personal pique which I have already touched upon, and doubtless reflected that he, at all events, had not greatly missed the help of the old heathens in his battle of life. When his own boys had passed through the approved curriculum of Public School and University, he viewed the question more liberally. One of the most pleasing characters in his later work, Mr. Crisparkle in Edwin Drood, is a classical tutor, and without shadow of humbug; indeed, he is perhaps the only figure in all Dickens presenting a fair resemblance to the modern type of English gentleman.

The year 1825, then, saw him at a day-school in North London: the ordinary day-school of that time, which is as much as to say that it was just better than no school at all. One cannot discover that he learnt anything there, or from any professed teacher elsewhere, beyond the very elements of common knowledge. And here again is a point on which throughout his life Dickens felt a certain soreness; he wished to be thought, wished to be, a well-educated man, yet was well aware that in several directions he could never make up for early defects of training. In those days it was socially more important than now to have received a "classical education", and with the classics he had no acquaintance. There is no mistaking the personal note in those passages of his books which treat of, or allude to, Greek and Latin studies in a satirical spirit. True, it is just as impossible to deny that, in this particular field of English life, every sort of insincerity was rampant. Carlyle (who, by the by, was no Grecian) threw scorn upon "gerund-grinding", and with justice; Dickens delighted in showing classical teachers as dreary humbugs, and in hinting that they were such by the mere necessity of the case. Mr. Feeder, B.A., grinds, with his Greek or Latin stop on, for the edification of Toots. Dr. Blimber snuffles at dinnertime, "It is remarkable that the Romans --", and every terrified boy assumes an air of impossible interest. Even Copperfield's worthy friend, Dr. Strong, potters in an imbecile fashion over a Greek lexicon which there is plainly not the slightest hope of his ever completing. Numerous are the side-hits at this educational idol of wealthy England. For all that, remember David's self-congratulation when, his school-days at an end, he feels that he is "well-taught"; in other words, that he is possessed of the results of Dr. Strong's mooning over dead languages. Dickens had far too much sense and honesty to proclaim a loud contempt where he knew himself ignorant. For an example of the sort of thing impossible to him, see the passage in an early volume of the Goncourts' Diary, where the egregious brothers report a quarrel with Saint-Victor, a defender of the Ancients; they, in their monumental fatuity, ending the debate by a declaration that a French novel called Adolphe was from every point of view preferable to Homer. Dickens knew better than this; but, having real ground for satire in the educational follies of the day, he indulged that personal pique which I have already touched upon, and doubtless reflected that he, at all events, had not greatly missed the help of the old heathens in his battle of life. When his own boys had passed through the approved curriculum of Public School and University, he viewed the question more liberally. One of the most pleasing characters in his later work, Mr. Crisparkle in Edwin Drood, is a classical tutor, and without shadow of humbug; indeed, he is perhaps the only figure in all Dickens presenting a fair resemblance to the modern type of English gentleman.

From George Gissing:

The catalogue of his early reading is most important; let it be given here, as Dickens gives it in David Copperfield, with additions elsewhere supplied. Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle, Humphrey Clinker, Tom Jones, The Vicar of Wakefield, Don Quixote, Gil Blas, Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, and Tales of the Genii; also volumes of Essayists: The Tatler, The Spectator, The Idler, The Citizen of the World, and a Collection of Farces edited by Mrs. Inchbald. These the child had found in his father's house at Chatham; he carried them with him in his head to London, and there found them his solace through the two years of bitter bondage. The importance of this list lies not merely in the fact that it certifies Dickens's earliest reading; it remained throughout his whole life (with very few exceptions) the sum of books dear to his memory and to his imagination. Those which he read first were practically the only books which influenced Dickens as an author. We must add the Bible (with special emphasis, the New Testament), Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Sterne; among his own contemporaries, Scott and Carlyle. Therewith we may close this tale of authors whom he notably followed through his youth of study and his career as man of letters. After success came to him (and it came so early) he never had much time for reading, and probably never any great inclination. We are told that he especially enjoyed books of travel, but they served merely as recreation. His own travels in Europe supplied him with no new authors (one hears of his trying to read some French novelist, and finding the dialogue intolerably dull), nor with any new mental pursuit. He learned to speak in French and Italian, but made very little use of the attainment. Few really great men can have had so narrow an intellectual scope. Turn to his practical interests, and there indeed we have another picture; I speak at present only of the book-lore which shaped his mind, and helped to direct his pen.

The catalogue of his early reading is most important; let it be given here, as Dickens gives it in David Copperfield, with additions elsewhere supplied. Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle, Humphrey Clinker, Tom Jones, The Vicar of Wakefield, Don Quixote, Gil Blas, Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, and Tales of the Genii; also volumes of Essayists: The Tatler, The Spectator, The Idler, The Citizen of the World, and a Collection of Farces edited by Mrs. Inchbald. These the child had found in his father's house at Chatham; he carried them with him in his head to London, and there found them his solace through the two years of bitter bondage. The importance of this list lies not merely in the fact that it certifies Dickens's earliest reading; it remained throughout his whole life (with very few exceptions) the sum of books dear to his memory and to his imagination. Those which he read first were practically the only books which influenced Dickens as an author. We must add the Bible (with special emphasis, the New Testament), Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Sterne; among his own contemporaries, Scott and Carlyle. Therewith we may close this tale of authors whom he notably followed through his youth of study and his career as man of letters. After success came to him (and it came so early) he never had much time for reading, and probably never any great inclination. We are told that he especially enjoyed books of travel, but they served merely as recreation. His own travels in Europe supplied him with no new authors (one hears of his trying to read some French novelist, and finding the dialogue intolerably dull), nor with any new mental pursuit. He learned to speak in French and Italian, but made very little use of the attainment. Few really great men can have had so narrow an intellectual scope. Turn to his practical interests, and there indeed we have another picture; I speak at present only of the book-lore which shaped his mind, and helped to direct his pen.

Julie wrote: "Does David not know Aunt Betsey has an estranged husband? I'm really surprised he doesn't start putting 2 and 2 together here."

I wonder, does he? I've never thought about it before. It doesn't see like something Aunt Betsey would bring up very often, so who would have told him?

I wonder, does he? I've never thought about it before. It doesn't see like something Aunt Betsey would bring up very often, so who would have told him?

Jantine wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Mrs. Crupp seems to be a milder version of Mrs. Gamp. I do like her, but wouldn't trust her."

Miss Mowcher reminded me of Mrs. Gamp more to be honest. I trust neither of them thou..."

Since Tristram likes Mrs. Crupp, here she is:

Miss Mowcher reminded me of Mrs. Gamp more to be honest. I trust neither of them thou..."

Since Tristram likes Mrs. Crupp, here she is:

And here is Martha:

Some day I am going to put every Kyd illustration I have ever come across in one thread. Some day.

Some day I am going to put every Kyd illustration I have ever come across in one thread. Some day.

Kim wrote: "I'm shaking my head at Kyd's idea of Steerforth:

Kim wrote: "I'm shaking my head at Kyd's idea of Steerforth:"

Surely Steerforth's clothes fit better than that.

Kim wrote: "When Kyd draws Littimer he draws this:

"

I’m holding my breath. This illustration of Littimer works in my imagination. Now, as for Steerforth, I agree with Julie. Is Steerforth supposed to look like a flapper?

As for Martha. I don’t imagine her looking like the illustration at all.

"

I’m holding my breath. This illustration of Littimer works in my imagination. Now, as for Steerforth, I agree with Julie. Is Steerforth supposed to look like a flapper?

As for Martha. I don’t imagine her looking like the illustration at all.

Peter wrote: "As for Martha. I don’t imagine her looking like the illustration at all".

If Martha looked like that I don't think she would have had to worry about becoming a fallen woman.

If Martha looked like that I don't think she would have had to worry about becoming a fallen woman.

Steerforth looks more like a teenager from the fifties who had just enough money to thrift a way too big jacket than a smooth, well dressed young Victorian man.

Jantine wrote: "Steerforth looks more like a teenager from the fifties who had just enough money to thrift a way too big jacket than a smooth, well dressed young Victorian man."

All I could think of when I saw it was Rob the Grinder from Dombey, it must be the clothes.

All I could think of when I saw it was Rob the Grinder from Dombey, it must be the clothes.

Kim wrote: "I've been thinking, David has always had someone watching out for him. His mother, Peggotty, Steerforth, his aunt, now he's going to be alone in London looking out for himself. Is he ready for that?"

Although I find him very passive at times, for example when he could join forces with Agnes and warn Mr. Wickfield against Heep's machinations, one has to give it to David that he freed himself from his factory life quite efficiently. He might still depend on Aunt Betsey, but the first step - that of going all the way to Dover and of finding the courage to undertake the journey instead of just resigning to Mr. Murdstone's plans for him - arose in David alone. And don't forget, he has Mrs. Crupp, who is chuffed to bits about having somebody to look after ;-)

Although I find him very passive at times, for example when he could join forces with Agnes and warn Mr. Wickfield against Heep's machinations, one has to give it to David that he freed himself from his factory life quite efficiently. He might still depend on Aunt Betsey, but the first step - that of going all the way to Dover and of finding the courage to undertake the journey instead of just resigning to Mr. Murdstone's plans for him - arose in David alone. And don't forget, he has Mrs. Crupp, who is chuffed to bits about having somebody to look after ;-)

Tristram wrote: "one has to give it to David that he freed himself from his factory life quite efficiently."

Tristram wrote: "one has to give it to David that he freed himself from his factory life quite efficiently."Sometimes this is the only thing that keeps me on David's side. At least he had the gumption to seek out Aunt Betsey.

Peter wrote: "One evening David surprises Steerforth who says “You come upon me like a reproachful ghost!” Later Steerforth wishes he had “a judicious father these last twenty years!"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OyyZ0...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OyyZ0...

Tristram wrote: "Yes, there is not a lot more to make him truly, truly likeable, up to now."

Yes, but he let that boy steal his money and his trunk on the way, and got taken advantage of by the creepy guy who bought his jacket, or coat, or shirt, or whatever he was selling.

Yes, but he let that boy steal his money and his trunk on the way, and got taken advantage of by the creepy guy who bought his jacket, or coat, or shirt, or whatever he was selling.

What happened to Steerforth's father, do we know? And why does no one ever have a father and a mother?

I'm making a list of one parent characters in this story:

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uriah Heep - mother

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uriah Heep - mother

Kim wrote: "I'm making a list of one parent characters in this story:

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uriah Heep - mo..."

Kim

Perhaps one parent families was a means to keep the novel under 1500 pages? :-)

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uriah Heep - mo..."

Kim

Perhaps one parent families was a means to keep the novel under 1500 pages? :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "The Micawber twins have two parents, for all the good it's doing them."

Very good Mary Lou I didn't think of them.

Very good Mary Lou I didn't think of them.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Yes, there is not a lot more to make him truly, truly likeable, up to now."

Yes, but he let that boy steal his money and his trunk on the way, and got taken advantage of by the cr..."

That does not make him exactly likeable to me. I can pity a person without liking them ;-)

Yes, but he let that boy steal his money and his trunk on the way, and got taken advantage of by the cr..."

That does not make him exactly likeable to me. I can pity a person without liking them ;-)

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "I'm making a list of one parent characters in this story:

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uri..."

Brilliant theory, Peter!!!

David - mother

Steerforth - mother

Agnes - father

Dora - father

Little Emily - neither

Ham - neither

Annie Strong - mother

Uri..."

Brilliant theory, Peter!!!

Kim wrote: "What happened to Steerforth's father, do we know? And why does no one ever have a father and a mother?"

I don't know that we ever learned what happened to Steerforth's father, but I think he would have been better off for having had a father to put some restraint on him. His mother is apparently so full of her son that she failed to imbue him with the necessary knowledge about the world not being a place for one person only. I remember that during her first meeting with David she told him that she chose Creakle's school because it would be a place where Steerforth's every whim was pandered to by a time-serving scoundrel posing as a headmaster - not exactly the words chosen by Mrs. Steerforth, but my one. Mrs. Steerforth has definitely made a monster of her child.

As to why there are so many incomplete families in the novel, I'd say that this must have been a faithful picture of contemporary reality. After all, many people would die young and leave children behind.

I don't know that we ever learned what happened to Steerforth's father, but I think he would have been better off for having had a father to put some restraint on him. His mother is apparently so full of her son that she failed to imbue him with the necessary knowledge about the world not being a place for one person only. I remember that during her first meeting with David she told him that she chose Creakle's school because it would be a place where Steerforth's every whim was pandered to by a time-serving scoundrel posing as a headmaster - not exactly the words chosen by Mrs. Steerforth, but my one. Mrs. Steerforth has definitely made a monster of her child.

As to why there are so many incomplete families in the novel, I'd say that this must have been a faithful picture of contemporary reality. After all, many people would die young and leave children behind.

Miss Mowcher

Harry Furniss