The Old Curiosity Club discussion

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 10-12

The first paragraph of Chapter 11was the saddest in the book for me so far:

"I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything; but it is matter of some surprise to me, even now, that I can have been so easily thrown away at such an age. A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily or mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign in my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby."

It is sad because Dickens is writing about his own childhood experiences at Warren's Blacking:

"It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age. It is wonderful to me that, even after my descent into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London, no one had compassion enough on me—a child of singular abilities, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally—to suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it might have been, to place me at any common school. Our friends, I take it, were tired out. No one made any sign. My father and mother were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar-school, and going to Cambridge."

Dickens describes Murdstone and Grinby's this way:

"Murdstone and Grinby's warehouse was at the waterside. It was down in Blackfriars. Modern improvements have altered the place; but it was the last house at the bottom of a narrow street, curving down hill to the river, with some stairs at the end, where people took boat. It was a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats. Its panelled rooms, discoloured with the dirt and smoke of a hundred years, I dare say; its decaying floors and staircase; the squeaking and scuffling of the old grey rats down in the cellars; and the dirt and rottenness of the place; are things, not of many years ago, in my mind, but of the present instant. They are all before me, just as they were in the evil hour when I went among them for the first time, with my trembling hand in Mr. Quinion's.

I know that a great many empty bottles were one of the consequences of this traffic, and that certain men and boys were employed to examine them against the light, and reject those that were flawed, and to rinse and wash them. When the empty bottles ran short, there were labels to be pasted on full ones, or corks to be fitted to them, or seals to be put upon the corks, or finished bottles to be packed in casks. All this work was my work, and of the boys employed upon it I was one.

There were three or four of us, counting me. My working place was established in a corner of the warehouse, where Mr. Quinion could see me, when he chose to stand up on the bottom rail of his stool in the counting-house, and look at me through a window above the desk. Hither, on the first morning of my so auspiciously beginning life on my own account, the oldest of the regular boys was summoned to show me my business. His name was Mick Walker, and he wore a ragged apron and a paper cap."

And Dickens describes Warren's Blacking in these words:

"The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old gray rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river..... When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist."

As to the boys working with David, Mick Walker's father was a bargeman, Mealy Potatoes's father was a waterman, and a fireman, and "was engaged as such at one of the large theatres; where some young relation of Mealy's - I think his little sister - did Imps in the Pantomimes." I have to look up what Imps are.

Dickens worked with Bob Fagin an orphan who lived with his brother-in-law, a waterman." "Poll Green's father had the additional distinction of being a fireman, and was employed at Drury Lane theatre; where another relation of Poll's, I think his little sister, did imps in the pantomimes."

So much of this chapter is autobiographical I could just keep comparing Dickens life with David's life and they match almost word for word. One thing that is different is the Micawbers. Charles had no such family to live with when he worked at the warehouse but was lodged with "a reduced old lady, long known to our family, in Little College Street, Camden-town, who took children in to board, and had once done so at Brighton; and who, with a few alterations and embellishments, unconsciously began to sit for Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey when she took in me."

David, however lodges with the Micawbers. He is introduced to Mr. Micawber by Mr. Quinion who tells him that he will be living with Mr. Micawber and his family. David describes Mr. Micawber as a "stoutest middle aged person" and going home with him that evening he meets Mrs. Micawber "a thin and faded lady, not at all young" and four young children.

David learns that the family has been forced to take in a lodger because Mr. Micawber is "in difficulties", and creditors appear at the house at all hours of the day. However, Mr. Micawber is always certain that something will turn up. I was glad to see that difficulties or not the Micawber's didn't take David's money that he offered them and they were kind to him, he says:

"A curious equality of friendship, originating, I suppose, in our respective circumstances, sprung up between me and these people, notwithstanding the ludicrous disparity in our years." Mr. Micawber (who was a thoroughly good-natured man, and as active a creature about everything but his own affairs as ever existed, and never so happy as when he was busy about something that could never be of any profit to him)

Eventually Mr. Micawber is arrested and taken to debtors' prison, where his family soon joins him and a little room is rented for David near the prison. Soon Mrs. Micawber informs David that her family has decided to help Mr. Micawber and he should be released in about six weeks. At which time Micawber says he will live in a new manner if something should turn up.

"I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything; but it is matter of some surprise to me, even now, that I can have been so easily thrown away at such an age. A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily or mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign in my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby."

It is sad because Dickens is writing about his own childhood experiences at Warren's Blacking:

"It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age. It is wonderful to me that, even after my descent into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London, no one had compassion enough on me—a child of singular abilities, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally—to suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it might have been, to place me at any common school. Our friends, I take it, were tired out. No one made any sign. My father and mother were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar-school, and going to Cambridge."

Dickens describes Murdstone and Grinby's this way:

"Murdstone and Grinby's warehouse was at the waterside. It was down in Blackfriars. Modern improvements have altered the place; but it was the last house at the bottom of a narrow street, curving down hill to the river, with some stairs at the end, where people took boat. It was a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats. Its panelled rooms, discoloured with the dirt and smoke of a hundred years, I dare say; its decaying floors and staircase; the squeaking and scuffling of the old grey rats down in the cellars; and the dirt and rottenness of the place; are things, not of many years ago, in my mind, but of the present instant. They are all before me, just as they were in the evil hour when I went among them for the first time, with my trembling hand in Mr. Quinion's.

I know that a great many empty bottles were one of the consequences of this traffic, and that certain men and boys were employed to examine them against the light, and reject those that were flawed, and to rinse and wash them. When the empty bottles ran short, there were labels to be pasted on full ones, or corks to be fitted to them, or seals to be put upon the corks, or finished bottles to be packed in casks. All this work was my work, and of the boys employed upon it I was one.

There were three or four of us, counting me. My working place was established in a corner of the warehouse, where Mr. Quinion could see me, when he chose to stand up on the bottom rail of his stool in the counting-house, and look at me through a window above the desk. Hither, on the first morning of my so auspiciously beginning life on my own account, the oldest of the regular boys was summoned to show me my business. His name was Mick Walker, and he wore a ragged apron and a paper cap."

And Dickens describes Warren's Blacking in these words:

"The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old gray rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river..... When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist."

As to the boys working with David, Mick Walker's father was a bargeman, Mealy Potatoes's father was a waterman, and a fireman, and "was engaged as such at one of the large theatres; where some young relation of Mealy's - I think his little sister - did Imps in the Pantomimes." I have to look up what Imps are.

Dickens worked with Bob Fagin an orphan who lived with his brother-in-law, a waterman." "Poll Green's father had the additional distinction of being a fireman, and was employed at Drury Lane theatre; where another relation of Poll's, I think his little sister, did imps in the pantomimes."

So much of this chapter is autobiographical I could just keep comparing Dickens life with David's life and they match almost word for word. One thing that is different is the Micawbers. Charles had no such family to live with when he worked at the warehouse but was lodged with "a reduced old lady, long known to our family, in Little College Street, Camden-town, who took children in to board, and had once done so at Brighton; and who, with a few alterations and embellishments, unconsciously began to sit for Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey when she took in me."

David, however lodges with the Micawbers. He is introduced to Mr. Micawber by Mr. Quinion who tells him that he will be living with Mr. Micawber and his family. David describes Mr. Micawber as a "stoutest middle aged person" and going home with him that evening he meets Mrs. Micawber "a thin and faded lady, not at all young" and four young children.

David learns that the family has been forced to take in a lodger because Mr. Micawber is "in difficulties", and creditors appear at the house at all hours of the day. However, Mr. Micawber is always certain that something will turn up. I was glad to see that difficulties or not the Micawber's didn't take David's money that he offered them and they were kind to him, he says:

"A curious equality of friendship, originating, I suppose, in our respective circumstances, sprung up between me and these people, notwithstanding the ludicrous disparity in our years." Mr. Micawber (who was a thoroughly good-natured man, and as active a creature about everything but his own affairs as ever existed, and never so happy as when he was busy about something that could never be of any profit to him)

Eventually Mr. Micawber is arrested and taken to debtors' prison, where his family soon joins him and a little room is rented for David near the prison. Soon Mrs. Micawber informs David that her family has decided to help Mr. Micawber and he should be released in about six weeks. At which time Micawber says he will live in a new manner if something should turn up.

In Chapter 12 Mr. Micawber is released from jail and his debts are resolved. Mrs. Micawber informs David that her family thinks leaving London would be best for Mr. Micawber and something could be done for him in Plymouth at a counting house. She becomes hysterical when David asks whether she will accompany him saying she will never desert Mr. Micawber. In a week they leave for Plymouth and David decides not to stay in London without them. He had grown accustomed to being with them, and felt friendless without them, going to new lodgings and among new people was something he couldn't stand. He knew it was up to him to get out of his present situation, he seldom heard from Miss Murstone and never from Mr. Murdstone, once in a while clothing would be sent to him with a note saying Murdstone trusted David was 8applying himself to his business, but never a hint of ever being anything else than what he was then. He decided he couldn't stay there and decided to leave and go to his aunt. He says he doesn't know how or when the idea of going to his Aunt Betsey and telling her his story came to him but now that it did he had to act upon it. David writes Peggotty for Miss Betsey's address and the loan of a half-guinea for travelling expenses without telling her why he needs the address or the half- guinea. When this arrives, he hires a young man with a cart to transport his trunk to the coach office, but the stranger steals his half-guinea and rides off with the trunk, just another person willing to take advantage or be nasty to a young boy. So poor David is left alone in London without luggage or funds to get to his aunt.

This installment ended with quite the cliffhanger:

"At length, confused by fright and heat, and doubting whether half London might not by this time be turning out for my apprehension, I left the young man to go where he would with my box and money; and, panting and crying, but never stopping, faced about for Greenwich, which I had understood was on the Dover Road: taking very little more out of the world, towards the retreat of my aunt, Miss Betsey, than I had brought into it, on the night when my arrival gave her so much umbrage."

The original readers had to wait a month to find out if David finds his aunt. I would like to say good riddance to the Murdstones but I would think even if Miss Murdstone doesn't care where David has disappeared to, perhaps Mr, Murdstone will look for him, at least for a short while, not through any compassion he has but perhaps from a sense of duty or firmness. :-) I'm off to find the illustrations. Oh, I almost forgot, I would have been out of there at the glimpse of the first rat.

This installment ended with quite the cliffhanger:

"At length, confused by fright and heat, and doubting whether half London might not by this time be turning out for my apprehension, I left the young man to go where he would with my box and money; and, panting and crying, but never stopping, faced about for Greenwich, which I had understood was on the Dover Road: taking very little more out of the world, towards the retreat of my aunt, Miss Betsey, than I had brought into it, on the night when my arrival gave her so much umbrage."

The original readers had to wait a month to find out if David finds his aunt. I would like to say good riddance to the Murdstones but I would think even if Miss Murdstone doesn't care where David has disappeared to, perhaps Mr, Murdstone will look for him, at least for a short while, not through any compassion he has but perhaps from a sense of duty or firmness. :-) I'm off to find the illustrations. Oh, I almost forgot, I would have been out of there at the glimpse of the first rat.

Kim wrote: "The first paragraph of Chapter 11was the saddest in the book for me so far:

Kim wrote: "The first paragraph of Chapter 11was the saddest in the book for me so far:"I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything; but it is matter ..."

Thank you for these quotes comparing Charles and David. I was also struck by that passage about David being thrown away. It's terrifically sad and still too true. I don't know if I've said this before, but I spent two summers in college working at a law office that was paid by the state to represent children in custody and delinquency cases, and sometimes instead of filing the files, I would read them, and it was shocking to me how terrible a parent had to be, and how many times, to lose custody of a child. When I read David Copperfield I find myself asking why didn't Pegotty interfere, or the local clergyman, but it was probably the same thing then that it is now: if a parent or legal guardian appears to be providing for a child, the law makes it very difficult for anyone to interfere. Technically, David is provided for.

I'm glad we have better child labor and education laws now, at least--although a student reminded me once when I was teaching Dickens that plenty of places in the world don't sound much better legally than 19th c London still, and those are the places where a lot of my stuff gets made.

On a brighter note, I love it when Peggotty shows David the room she will always keep for him. I can't help but feel that must have made a difference for him psychologically even though it turns out to be useless practically, since even the money she sends him is lost.

Kim wrote: "I was surprised they had set a certain time to return, or that they wanted him to return at all, but he's back. Why didn't he just stay with Peggotty? The Murdstones don't want him so why is he returning other than the story must go on? Does anyone know?.."

Kim wrote: "I was surprised they had set a certain time to return, or that they wanted him to return at all, but he's back. Why didn't he just stay with Peggotty? The Murdstones don't want him so why is he returning other than the story must go on? Does anyone know?.."I've had quite a few dogs over the years (all of them friendlier than Murdstone, by the way). Let's say Rover doesn't particularly like carrots. But if the other dogs are getting carrots, you can bet that Rover's going to take his and (eventually) eat it. He may not enjoy it, but he'll be darned if any of the other dogs are going to get it! Murdstone doesn't want David, but that doesn't mean he wants someone else to have him. Especially someone less firm ... and we all know how squishy Peggotty can be. I'd say Murdstone's an old cur, but that would be insulting to dogs.

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "I was surprised they had set a certain time to return, or that they wanted him to return at all, but he's back. Why didn't he just stay with Peggotty? The Murdstones don't want him so w..."

Mary Lou

Your comment is priceless and spot on as well.

Mary Lou

Your comment is priceless and spot on as well.

There was so much in this week's installment that I had to take notes. I'll try to be succinct with my observations.

There was so much in this week's installment that I had to take notes. I'll try to be succinct with my observations. Chapter 10

Tristram can tell me if I'm using this word correctly, but I felt a great sense of sehnsucht (longing for some idyllic, unattainable life?) when I read this:

The idea of being again surrounded by those honest faces, shining welcome on me; of renewing the peacefulness of the sweet Sunday morning, when the bells were ringing, the stones dropping in the water, and the shadowy ships breaking through the mist; of roaming up and down with little Em'ly, telling her my troubles, and finding charms against them in the shells and pebbles on the beach; made a calm in my heart.

Compare that to David's reality upon his arrival in Yarmouth:

Now, the whole place was, or it should have been, quite as delightful a place as ever; and yet it did not impress me in the same way. I felt rather disappointed with it.

What a letdown. Foreshadowing of things to come?

Speaking of foreshadowing, there's this:

...a curious feeling came over me that made me pretend not to know her [Em'ly], and pass by as if I were looking at something a long way off. I have done such a thing since in later life, or I am mistaken.

What's he alluding to?

David's excessive praise of Steerforth was disturbing. Talk about hero worship! Any relationship that unbalanced can't be healthy. Em'ly's attentiveness to David's approbations caused some red flags to go up.

I think the courtship between Barkis and Peggotty has been a pure delight. I love how she giggles like a schoolgirl, and how Barkis has been able to make so much headway with so little interaction. I do hope that Kim is wrong and he won't turn out to be a Scrooge. Maybe his frugal nature will merely be an endearing quirk. Peggotty seems to have enough backbone to keep him in line.

Should we pay attention to the Foxe's Book of Martyrs on Peggotty's shelf? Hmm....

Julie wrote: "Thank you for these quotes comparing Charles and David. "

Julie wrote: "Thank you for these quotes comparing Charles and David. "Yes, thank you, Kim. That was really something to read them together that way. So sad. This sentence really stood out:

...my hopes of growing up to be a learned and distinguished man, crushed in my bosom. The deep remembrance of the sense I had, of being utterly without hope now; of the shame I felt in my position; of the misery it was to my young heart to believe that day by day what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in, and raised my fancy and my emulation up by, would pass away from me, little by little, never to be brought back any more; cannot be written.

In answer to Kim's question about David's age, it says he was 10 at this point. Back to the reliability of the narrator, would a 10-year-old have the wisdom - if that's the right word - to see the big picture, and how all of this would impact his life? I suppose it's possible that he felt it in intangible ways, but it's obviously the retrospective adult David who was able to articulate it so well.

This bit about Mrs. Micawber's changeable nature stood out to me:

On one occasion...I saw her lying (of course with a twin) under the grate in a swoon, with her hair all torn about her face; but I never knew her more cheerful than she was, that very same night, over a veal cutlet before the kitchen fire, telling me stories about her papa and mama, and the company they used to keep.

What on Earth? I assume that's a fireplace grate, and not a grate in the gutter (if they had such things then). Was she passed out from hunger? Drink? Just exhausted and trying to stay warm? Whatever the case, I took a moment to thank the Lord for birth control. It made it easier to understand Mr. Kenwigs in Nicholas Nickleby, who was less than delighted when his wife had another baby, though the Kenwigs were certainly better off than the Micawbers.

Was it Peter who was keeping an eye on food? Lots of details about David's sustenance in this chapter.

Consider this:

That I suffered in secret, and that I suffered exquisitely, no one ever knew but I. How much I suffered, it is, as I have said already, utterly beyond my power to tell. But I kept my own counsel, and I did my work.

We know Dickens didn't tell many about his childhood. Apparently David, too, suffered in silence. Compare that with the Micawbers who seemingly cry more than Little Nell. David does his share of sobbing, too, but seems to have the decency to try to keep it to himself. But, my goodness, there are a lot of tears in this book!

Things I had to look up in this chapter:

Egg-hot - a drink consisting of beer, eggs, nutmeg, and sometimes other spices.

Quinion - five sheets of paper, that when folded for a book create ten pages. I can't make anything out of that one.

Fun name: Mealy Potatoes (though maybe not so fun for Mealy, himself)

I think you are right about that, Mary Lou. The 'I don't want it, but it's mine, so no one else can have it'-thought is quite common. On quite another level you see it with people who want to sell their stuff second-hand but can't sell it because their price is too dear, or who don't even try. 'I payed a lot for it 10 years ago, so it's worth a lot!' and because they paid a lot for it (like Murdstone apparently did with David's education - although I wouldn't be surprised if it turns out aunt Betsey paid for that or something like that) they don't want someone else to 'just have it for free/cheap'.

I did wonder, if David got such a good education according to Murdstone, why would he have been sent to do such a drugery-job? Wouldn't he bring in much more if he'd been apprenticed in the offices to add numbers or write the letters or something like that, because people who can read and write cost a lot more in wages than a boy labeling and corking bottles? But apparently either David did not get a good education at all (which is ... not that far off with Creakle, but he could at least read and write, we know as much) or the Murdstones didn't care and just wanted him as miserable as possible. Again.

I did wonder, if David got such a good education according to Murdstone, why would he have been sent to do such a drugery-job? Wouldn't he bring in much more if he'd been apprenticed in the offices to add numbers or write the letters or something like that, because people who can read and write cost a lot more in wages than a boy labeling and corking bottles? But apparently either David did not get a good education at all (which is ... not that far off with Creakle, but he could at least read and write, we know as much) or the Murdstones didn't care and just wanted him as miserable as possible. Again.

Chapter 12

Chapter 12I mentioned Peggotty's martyr book earlier. If we define martyr loosely as someone who seems to get some enjoyment or satisfaction out of suffering, rather than someone willing to die for a cause, we seem to have a few martyrs so far. Mrs. Gummidge, certainly. And I'd say that Mrs. Micawber is a bit of a martyr, too. If she's to be believed, she's sacrificed her position and her possessions for her marriage to a man with no ambition or sense of responsibility. Unlike David, Mrs. Micawber doesn't suffer in silence. What other martyrs will we encounter as we go along?

Kim wrote: "I would think even if Miss Murdstone doesn't care where David has disappeared to, perhaps Mr, Murdstone will look for him, at least for a short while, not through any compassion he has but perhaps from a sense of duty or firmness. ..."

I have a horrible feeling that Kim's right. It's that whole dog with the carrot thing. I can't think of any reason Murdstone would - legally speaking - have to keep David under his thumb, but maybe there's something in a will somewhere that we don't know about yet. I wish he'd just leave David alone.

I remember enjoying Aunt Betsey the last time I read this, and I'm very much looking forward to meeting her again! I'm sure we'll hear a bit about David's peregrinations first. Now that that horrible person (undoubtedly a cousin of the waiter) has made off with David's trunk and money, David won't have an easy journey.

Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages of the book only to find the next 600 pages a bit of a slog. By the end I was happy to get rid of the loose baggy monster and move on to something lighter and more concise. Please reassure me that I only thought so because I was a younger, less tolerant reader back then and that my opinion will have changed this time around!

Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages of the book only to find the next 600 pages a bit of a slog. By the end I was happy to get rid of the loose baggy monster and move on to something lighter and more concise. Please reassure me that I only thought so because I was a younger, less tolerant reader back then and that my opinion will have changed this time around!

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram can tell me if I'm using this word correctly, but I felt a great sense of sehnsucht (longing for some idyllic, unattainable life?) when I read this:"

The word is absolutely spot-on, and it is a very strong word - but so is the feeling if you long for something from your past. I found the observation made by David so true: Often when you revisit places or scenes where you used to be especially happy and / or impressed, you find yourself subject to a little disappointment, don't you? In my holidays I went to Arnsberg with my family, which is a town where I spent two years, training to be a teacher, and I was looking forward to seeing the place again because I really loved the medieval town centre. But there were some disappointments linked with my recent visit: For starters, the place where I used to live is now owned by a different family, and the butcher's shop (my former landlord was a butcher) is closed. Then I found that the castle ruins were being renovated because some of the walls were prone to crumbling down, and the place was something of a building site. The Irish pub where I spent so many jolly evenings also had a new landlord, and there were none of the faces I remembered of old. It was, pardon the pun, in fact quite sobering.

It is a dire truth that the past is the only land - apart from North Korea - you cannot travel to.

The word is absolutely spot-on, and it is a very strong word - but so is the feeling if you long for something from your past. I found the observation made by David so true: Often when you revisit places or scenes where you used to be especially happy and / or impressed, you find yourself subject to a little disappointment, don't you? In my holidays I went to Arnsberg with my family, which is a town where I spent two years, training to be a teacher, and I was looking forward to seeing the place again because I really loved the medieval town centre. But there were some disappointments linked with my recent visit: For starters, the place where I used to live is now owned by a different family, and the butcher's shop (my former landlord was a butcher) is closed. Then I found that the castle ruins were being renovated because some of the walls were prone to crumbling down, and the place was something of a building site. The Irish pub where I spent so many jolly evenings also had a new landlord, and there were none of the faces I remembered of old. It was, pardon the pun, in fact quite sobering.

It is a dire truth that the past is the only land - apart from North Korea - you cannot travel to.

As so many of you have already pointed out, these chapters do bear a vivid sign of Dickens's feeling of betrayal when he had to work at Warrens' as a child. I once read that he particularly regretted the lack of education these weeks at the factory meant for him, and he has passed on this feeling of regret to David, who laments that his faculties and his potential were left lying fallow. It is, of course, due to the malice and spite of the Murdstones that David has to do menial work instead of being educated.

Why does Mr. Murdstone do his worst by David? I think this is because he resents the fact that while his own son died soon after his mother, his step-child still lives. This resentment also prevents him from forming some ties with David via their grief for the late family members. In a way, we have the Dombey situation here, only Mr. Murdstone is more evil than Mr. Dombey ever was. David himself says that Mr. Murdstone is not only sad and full of grief, but also angry - and I think that the source of his anger lies in the fact that it is David who lives and his own son who died.

Why does Mr. Murdstone do his worst by David? I think this is because he resents the fact that while his own son died soon after his mother, his step-child still lives. This resentment also prevents him from forming some ties with David via their grief for the late family members. In a way, we have the Dombey situation here, only Mr. Murdstone is more evil than Mr. Dombey ever was. David himself says that Mr. Murdstone is not only sad and full of grief, but also angry - and I think that the source of his anger lies in the fact that it is David who lives and his own son who died.

Ulysse wrote: "Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages of the book only..."

I agree that it is very difficult to spot a coherent, speedy plotline in these first chapters, and that may make it difficult to stick to the book. On the other hand, we see Dickens at his best with regard to world-building: There are so many characters, and so many potential conflicts already and it is obvious that he is going to put the whole novel into higher gear sooner or later ...

I agree that it is very difficult to spot a coherent, speedy plotline in these first chapters, and that may make it difficult to stick to the book. On the other hand, we see Dickens at his best with regard to world-building: There are so many characters, and so many potential conflicts already and it is obvious that he is going to put the whole novel into higher gear sooner or later ...

Tristram wrote: "we have the Dombey situation here, only Mr. Murdstone is more evil than Mr. Dombey ever was...."

Tristram wrote: "we have the Dombey situation here, only Mr. Murdstone is more evil than Mr. Dombey ever was...."Certainly you're correct that Murdstone resents David for living when Murdstone's son is dead. But I take exception to your contention that Murdstone is more evil than Dombey (at least up to this point - he may surpass Dombey later). Florence was his first child, and his flesh and blood. Murdstone hardly knew David. They're both awful, but it's much crueler to treat one's own child that way. Seems so to me, anyway.

"Ulysse wrote: "Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? ..."

I'm enjoying the book so much that I had to think about this question. Yes - I have to agree that his time in London and his second visit to Yarmouth weren't quite as interesting as the first 9 chapters, but I still found them engaging and enjoyable.

When I first read Copperfield I was not yet interested in Dickens, and had no idea that it had an autobiographical element. I can imagine that his time at the boot factory was not an enjoyable portion for me at that time. As long-time group members know, I'm all about Dickens' warmth and humor. But reading it now for the second time, after having read all of his other novels, a few biographies, several Sketches, some correspondence, etc. I find chapter 11 just fascinating.

I wasn't so much thinking of plot, which for me always comes second to writing. After all my favorite Dickens, Pickwick, doesn't have much of a plot to speak of. It's freewheeling' Dickens all the way and it's a pure delight. Here in Copperfield we can feel that Dickens is trying to impose a form, establishing all these different plot lines, so many plot lines, enough for 8 novels, which we know will be all tied up nicely at the end thanks to his favorite device: coincidence. I am already tired in anticipation!

I wasn't so much thinking of plot, which for me always comes second to writing. After all my favorite Dickens, Pickwick, doesn't have much of a plot to speak of. It's freewheeling' Dickens all the way and it's a pure delight. Here in Copperfield we can feel that Dickens is trying to impose a form, establishing all these different plot lines, so many plot lines, enough for 8 novels, which we know will be all tied up nicely at the end thanks to his favorite device: coincidence. I am already tired in anticipation!But you're absolutely right, there's much more to Dickens than the melodrama of his somewhat poor plotting. I envy those of you who've been reading Dickens chronologically from the start. To have gotten this far means you've been immersed in the world he created for several years now. So far I've only been a tourist in Dickensland. But I intend to set up permanent residency there!

Mary Lou wrote: "Julie wrote: "Thank you for these quotes comparing Charles and David. "

Yes, thank you, Kim. That was really something to read them together that way. So sad. This sentence really stood out:

......"

Hi Mary Lou

Yes I’m the food man, both in search of it and its diners and their circumstances in this book and in my own refrigerator. :-)

To me, it’s fascinating to be drawn into various threads in Dickens’s novels. Dickens’s mention of birds, book titles, food, people’s homes and rooms and the weather always make me pause and take a closer look or two or ...

Yes, thank you, Kim. That was really something to read them together that way. So sad. This sentence really stood out:

......"

Hi Mary Lou

Yes I’m the food man, both in search of it and its diners and their circumstances in this book and in my own refrigerator. :-)

To me, it’s fascinating to be drawn into various threads in Dickens’s novels. Dickens’s mention of birds, book titles, food, people’s homes and rooms and the weather always make me pause and take a closer look or two or ...

Ulysse wrote: "I envy those of you who've been reading Dickens chronologically from the start. To have gotten this far means you've been immersed in the world he created for several years now. So far I've only been a tourist in Dickensland. But I intend to set up permanent residency there!."

Ulysse wrote: "I envy those of you who've been reading Dickens chronologically from the start. To have gotten this far means you've been immersed in the world he created for several years now. So far I've only been a tourist in Dickensland. But I intend to set up permanent residency there!."On the upside, you're coming in fresh, Ulysse! I had to take a break at Martin Chuzzlewit because Dickens was starting to feel like an uncle who had stayed to visit too long: love his quirks, had seen a bit too much of them. :)

Ulysse wrote: "Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages of the book only..."

Hi Ulysse

If its been 15 years since you last reading of DC I’m sure you will find many old favourite people and passages to meet up with again. In other parts of the novel you may stumble now where you glided before. There will also be delights you slipped by or forgot last time that emerge.

To me, a good book is never the same each time I read it, not because it has changed but rather because I have changed.

Hi Ulysse

If its been 15 years since you last reading of DC I’m sure you will find many old favourite people and passages to meet up with again. In other parts of the novel you may stumble now where you glided before. There will also be delights you slipped by or forgot last time that emerge.

To me, a good book is never the same each time I read it, not because it has changed but rather because I have changed.

Peter wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages o..."

Peter wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Is it just me or are these chapters a little boring compared to the incredible first three instalments? On my first reading of DC 15 years ago I remember loving the first 200 pages o..."Wise words, Peter. Reminds me of that fragment by Heraclitus: "you can't step into the same river twice" whose conclusion might have been: for the river is constantly changing, and so are you.

Julie wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "I envy those of you who've been reading Dickens chronologically from the start. To have gotten this far means you've been immersed in the world he created for several years now. So f..."

Julie wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "I envy those of you who've been reading Dickens chronologically from the start. To have gotten this far means you've been immersed in the world he created for several years now. So f..."Ha! Dickens: everyone's favorite annoying uncle.

Julie wrote: "On the upside, you're coming in fresh, Ulysse! I had to take a break at Martin Chuzzlewit because Dickens was starting to feel like an uncle who had stayed to visit too long: love his quirks, had seen a bit too much of them. :)"

And it's good to have you back, Julie!

And it's good to have you back, Julie!

In one of the earlier threads I mentioned that David is not wholly to my liking, and since we have been talking about the presentation of class differences in Dickens, I'd like to point out that in these here chapters, David repeatedly points out that although he was forced to do the same menial works as boys like Mick Walker and Mealy Potatoes, yet it was clear to everyone that he was not one of them, and it may not have been any less clear for David's want of its being clear. In fact, he seems very satisfied at finding the boys calling him "the little gent" or "the young Suffolker", thus acknowledging that there is a social barrier between him and them. In his breaks from work, he also makes a point of not joining the others but of spending his time on his own instead. Here, David is kept aloof from his fellow-workers by his class consciousness.

I don't know whether this is a mere coincidence or a tongue-in-cheek hint by the author, but Mr. Micawber strikes me as a more ludicrous simile of David: He is as down-at-the-heels as can be, but he still maintains the airs of a gentleman and is a grandiloquent as ever. It is definitely no coincidence that David and the Micawbers get on so well with each other because not only do they stem from the same class but they also have to live with the same tension between their pretensions and their actual social situation.

I don't know whether this is a mere coincidence or a tongue-in-cheek hint by the author, but Mr. Micawber strikes me as a more ludicrous simile of David: He is as down-at-the-heels as can be, but he still maintains the airs of a gentleman and is a grandiloquent as ever. It is definitely no coincidence that David and the Micawbers get on so well with each other because not only do they stem from the same class but they also have to live with the same tension between their pretensions and their actual social situation.

Mary Lou wrote: "But I take exception to your contention that Murdstone is more evil than Dombey (at least up to this point - he may surpass Dombey later). Florence was his first child, and his flesh and blood. Murdstone hardly knew David. They're both awful, but it's much crueler to treat one's own child that way. Seems so to me, anyway."

You are certainly right in saying that Dombey's neglect of Florence, his child, was direly heartless and cruel, but what I meant was this: As cruel as Dombey's treatment of Florence was, I would still think that he neglected her not so much out of conscious cruelty - the way Murdstone takes pleasure in torturing David - but rather out of pride and thoughtlessness. While Dombey learnt his lesson, the hard way, I doubt that a similar learning process would be viable to Murdstone since he actually enjoys being cruel, which, I think, cannot be said for Dombey.

You are certainly right in saying that Dombey's neglect of Florence, his child, was direly heartless and cruel, but what I meant was this: As cruel as Dombey's treatment of Florence was, I would still think that he neglected her not so much out of conscious cruelty - the way Murdstone takes pleasure in torturing David - but rather out of pride and thoughtlessness. While Dombey learnt his lesson, the hard way, I doubt that a similar learning process would be viable to Murdstone since he actually enjoys being cruel, which, I think, cannot be said for Dombey.

Tristram wrote: "And it's good to have you back, Julie!"

Tristram wrote: "And it's good to have you back, Julie!"Thank you! I am glad to be back, and also glad Martin C was so long that the break cleared my head altogether and I had a great time reading Dombey.

That's a good point about David and the Micawbers. I had seen them as being very different from him because David is so naive, but really the Micawbers are extremely naive in their own way. Mr. Micawber understands at some level that he is responsible for his circumstances--his advice to David about living just under your income instead of just over it shows that--but he seems completely oblivious to his own continuing failure to take that advice.

Tristram wrote: "I'd like to point out that in these here chapters, David repeatedly points out that although he was forced to do the same menial works as boys like Mick Walker and Mealy Potatoes, yet it was clear to everyone that he was not one of them, and it may not have been any less clear for David's want of its being clear. In fact, he seems very satisfied at finding the boys calling him "the little gent" or "the young Suffolker", thus acknowledging that there is a social barrier between him and them. In his breaks from work, he also makes a point of not joining the others but of spending his time on his own instead. Here, David is kept aloof from his fellow-workers by his class consciousness."

Tristram wrote: "I'd like to point out that in these here chapters, David repeatedly points out that although he was forced to do the same menial works as boys like Mick Walker and Mealy Potatoes, yet it was clear to everyone that he was not one of them, and it may not have been any less clear for David's want of its being clear. In fact, he seems very satisfied at finding the boys calling him "the little gent" or "the young Suffolker", thus acknowledging that there is a social barrier between him and them. In his breaks from work, he also makes a point of not joining the others but of spending his time on his own instead. Here, David is kept aloof from his fellow-workers by his class consciousness."What's odd about this to me is that I feel grown-David/Dickens approves of this behavior, but did not approve of child-David distinguishing himself from the Peggottys to Steerforth. When he speaks to Steerforth, grown-David takes a lot of effort to explain child-David's behavior as if he is ashamed of it now and feels it needs explaining:

I am not sure whether it was in the pride of having such a friend as Steerforth, or in the desire to explain to him how I came to have such a friend as Mr. Peggotty, that I called to him as he was going away. But I said, modestly—Good Heaven, how it all comes back to me this long time afterwards—!

But I'm not remembering any such regretful explanation when he talks about distinguishing himself from the other boys who work with him? There, it's more like he's pointing out that he retained his gentlemanliness by refraining from low company even in lonely times.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I'd like to point out that in these here chapters, David repeatedly points out that although he was forced to do the same menial works as boys like Mick Walker and Mealy Potatoes, ..."

Good point, Julie. I guess that Dickens approved of child-David's desire to keep a distance from the working class boys because, maybe, when child-Dickens was in the same situation, he did the same.

Good point, Julie. I guess that Dickens approved of child-David's desire to keep a distance from the working class boys because, maybe, when child-Dickens was in the same situation, he did the same.

This chapter gives us the marriage of Peggotty to Barkis and the innocent hope of another. David recognizes that Em’ly is becoming even more beautiful and hopes that he might “grow up to marry Em’ly.” David’s innocence has a fairytale like glow. He sees himself and Em’ly “going away anywhere to live among the trees and in the fields, never growing older, never growing wiser, children ever, rambling hand in hand through sunshine and among flowery meadows.” The sounds and dreams of the innocent.

As mentioned earlier, Fox’s Book of Martyrs and Peggotty’s crocodile-book are part of David’s remembrance as well as “passing an afternoon ... reading some books.” David realizes that “but for the old books [that] ... [he] read over and over I don’t know how many times more” his life would have been one of constant misery. These books, perhaps just faintly recalled, are what buttressed David against the Murdstone’s who “coldly neglected” him. Fantasy and fairy tales and childish naïveté are David’s survival coping skills against the fact that the Murdstone’s intended to get rid of him.

As mentioned earlier, Fox’s Book of Martyrs and Peggotty’s crocodile-book are part of David’s remembrance as well as “passing an afternoon ... reading some books.” David realizes that “but for the old books [that] ... [he] read over and over I don’t know how many times more” his life would have been one of constant misery. These books, perhaps just faintly recalled, are what buttressed David against the Murdstone’s who “coldly neglected” him. Fantasy and fairy tales and childish naïveté are David’s survival coping skills against the fact that the Murdstone’s intended to get rid of him.

I do think there is a difference, although in neither situation his behaviour is good in my 21st century eyes.

During the later period David is consumed by base problems, by getting enough food in his belly, he is shown there is more to being poor than just not living in a big house. With the Peggotties, he saw the life of poor people living within their means, while with the Micawbers he saw the distress that is made by not knowing how to do so. He saw the practicalities of Micawber's advise, even if he didn't realise so as a child. Also, while at school, he had friends/peers that were in the same situation he was in, while here Micawber of course was 'old' (at least, not a child) and the boys at his work had known they would have to go working since forever, and had a family who perhaps were poor and couldn't pay for their upkeep, but they would've gotten them out of there if they could have. David, meanwhile, knew that his stepfamily sent him there, even if they could've kept him/sent him somewhere else. Also, David now had his mind troubled with base things like how to get food in his hungry, tired belly, and having to work about 12 hours a day. He, in short, desperately needed something to cling to, something that might mean this dire situation would not stay for the rest of his life.

While at school, he didn't need this so desperately. He was fed, got an education (even if not a good one), and he was away from the Murdstones, so he had much more comfort and with that mental capacity to realise he was unfair to the Peggotties than he had mental capacity to realise he was unfair to his peers at the wine place.

During the later period David is consumed by base problems, by getting enough food in his belly, he is shown there is more to being poor than just not living in a big house. With the Peggotties, he saw the life of poor people living within their means, while with the Micawbers he saw the distress that is made by not knowing how to do so. He saw the practicalities of Micawber's advise, even if he didn't realise so as a child. Also, while at school, he had friends/peers that were in the same situation he was in, while here Micawber of course was 'old' (at least, not a child) and the boys at his work had known they would have to go working since forever, and had a family who perhaps were poor and couldn't pay for their upkeep, but they would've gotten them out of there if they could have. David, meanwhile, knew that his stepfamily sent him there, even if they could've kept him/sent him somewhere else. Also, David now had his mind troubled with base things like how to get food in his hungry, tired belly, and having to work about 12 hours a day. He, in short, desperately needed something to cling to, something that might mean this dire situation would not stay for the rest of his life.

While at school, he didn't need this so desperately. He was fed, got an education (even if not a good one), and he was away from the Murdstones, so he had much more comfort and with that mental capacity to realise he was unfair to the Peggotties than he had mental capacity to realise he was unfair to his peers at the wine place.

Mary Lou wrote: "I've had quite a few dogs over the years (all of them friendlier than Murdstone, by the way). Let's say Rover doesn't particularly like carrots. But if the other dogs are getting carrots, ..."

You are tempting me to get another dog to see if I can get Willow to take her joint suppliment by offering it to the other dog first. Maybe I'll name the new dog Murdstone.

You are tempting me to get another dog to see if I can get Willow to take her joint suppliment by offering it to the other dog first. Maybe I'll name the new dog Murdstone.

It seems that books are everywhere in the novel so far. In chapter 11 David tells us he carried his bread under his arm like a book. Later we learn that Mr Micawber “had a few books on a little chiffonier” that later were sold to a bookseller on the City Road that was almost “all bookstalls and bird-shops.” When Micawber is in jail David’s mind connects the incident to when “Roderick Random was in debtor’s prison.” Very often, David connects the events that happen to him through the mention or connection to books. To David, like to Dickens himself, books became a way to come to terms with his own life.

As Kim mentioned above, this chapter is very autobiographical. Dickens’s father, like Micawber, was sent to jail for debt. This chapter is eerie in many ways.

As Kim mentioned above, this chapter is very autobiographical. Dickens’s father, like Micawber, was sent to jail for debt. This chapter is eerie in many ways.

Tristram wrote: "I spent two years, training to be a teacher, and I was looking forward to seeing the place again..."

Did you pass? :-)

Did you pass? :-)

Tristram wrote: "In one of the earlier threads I mentioned that David is not wholly to my liking, and since we have been talking about the presentation of class differences in Dickens, I'd like to point out that in..."

I don't remember anyone ever being to your liking, except the bad guys of course.

I don't remember anyone ever being to your liking, except the bad guys of course.

Grandiloquent? Really? Yes I had to look it up, again:

pompous or extravagant in language, style, or manner, especially in a way that is intended to impress.

pompous or extravagant in language, style, or manner, especially in a way that is intended to impress.

Tristram wrote: "David repeatedly points out that although he was forced to do the same menial works as boys like Mick Walker and Mealy Potatoes, yet it was clear to everyone that he was not one of them, and it may not have been any less clear for David's want of its being clear. "

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

"But I held some station at the blacking-warehouse too. Besides that my relative at the counting-house did what a man so occupied, and dealing with a thing so anomalous, could, to treat me as one upon a different footing from the rest, I never said, to man or boy, how it was that I came to be there, or gave the least indication of being sorry that I was there. That I suffered in secret, and that I suffered exquisitely, no one ever knew but I. How much I suffered, it is, as I have said already, utterly beyond my power to tell. No man's imagination can overstep the reality. But I kept my own counsel, and I did my work. I knew from the first that, if I could not do my work as well as any of the rest, I could not hold myself above slight and contempt. I soon became at least as expeditious and as skillful with my hands as either of the other boys. Though perfectly familiar with them, my conduct and manners were different enough from theirs to place a space between us. They, and the men, always spoke of me as 'the young gentleman.' A certain man (a soldier once) named Thomas, who was the foreman, and another named Harry, who was the carman and wore a red jacket, used to call me 'Charles' sometimes, in speaking to me; but I think it was mostly when we were very confidential, and when I had made some efforts to entertain them over our work with the results of some of the old readings, which were fast perishing out of my mind. Poll Green uprose once, and rebelled against the 'young gentleman' usage; but Bob Fagin settled him speedily.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

"But I held some station at the blacking-warehouse too. Besides that my relative at the counting-house did what a man so occupied, and dealing with a thing so anomalous, could, to treat me as one upon a different footing from the rest, I never said, to man or boy, how it was that I came to be there, or gave the least indication of being sorry that I was there. That I suffered in secret, and that I suffered exquisitely, no one ever knew but I. How much I suffered, it is, as I have said already, utterly beyond my power to tell. No man's imagination can overstep the reality. But I kept my own counsel, and I did my work. I knew from the first that, if I could not do my work as well as any of the rest, I could not hold myself above slight and contempt. I soon became at least as expeditious and as skillful with my hands as either of the other boys. Though perfectly familiar with them, my conduct and manners were different enough from theirs to place a space between us. They, and the men, always spoke of me as 'the young gentleman.' A certain man (a soldier once) named Thomas, who was the foreman, and another named Harry, who was the carman and wore a red jacket, used to call me 'Charles' sometimes, in speaking to me; but I think it was mostly when we were very confidential, and when I had made some efforts to entertain them over our work with the results of some of the old readings, which were fast perishing out of my mind. Poll Green uprose once, and rebelled against the 'young gentleman' usage; but Bob Fagin settled him speedily.

Mrs. Gummidge casts a damp on our departure

Chapter 10

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the fourth monthly part, Phiz reverts to the relationship between David and his second family, the Peggottys, as the wooing by Mr. Barkis of Clara reaches closure after the kind-hearted servant's being discharged by the cold, controlling Murdstones. Steig singles this illustration out for commendation because of Phiz's deft placement of a single symbol (the broken chain) and the overall organization of the figures as he captures a precise moment in the narrative, namely Mrs. Gummidge's receiving from Dan'l Peggotty an old shoe to toss after the newly-weds in order to confer luck and prosperity upon them, a tradition going back at least to Tudor times, and probably much earlier:

With no more than one (possible) emblem, "Mrs. Gummidge casts a damp on our departure" (ch. 10) seems more successful artistically in its representation of, the infantile adult couple (Barkis and Peggotty) and the precocious child couple (David and Emily); there is a spirited horse and fine, open handling of the boat house and the sea, and only the chain linked to a broken piling in the left foreground may comment unobtrusively on the perils of marriage, which the rest of the novel is at some pains to elaborate. [Steig 116]

The moment in question comes as the climax of David's narrative of the preparations for the "outing," which is an abbreviated honeymoon for the parsimonious carrier:

At length, when the term of my visit was nearly expired, it was given out that Peggotty and Mr. Barkis were going to make a day's holiday together, and that little Em'ly and I were to accompany them. I had but a broken sleep the night before, in anticipation of the pleasure of a whole day with Em'ly. We were all astir betimes in the morning; and while we were yet at breakfast, Mr. Barkis appeared in the distance, briskly driving a chaise-cart towards the object of his affections.

Peggotty was dressed as usual, in her neat and quiet mourning; but Mr. Barkis bloomed in a new blue coat, of which the tailor had given him such good measure, that the cuffs would have rendered gloves unnecessary in the coldest weather, while the collar was so high that it pushed his hair up on end on the top of his head. His bright buttons, too, were of the largest size. Rendered complete by drab pantaloons and a buff waistcoat, I thought Mr. Barkis a phenomenon of respectability.

When we were all in a bustle outside the door, I found that Mr. Peggotty was prepared with an old shoe, which was to be thrown after us for luck, and which he offered to Mrs. Gummidge for that purpose.

"No. It had better be done by somebody else, Dan'l," said Mrs. Gummidge. "I'm a lone lorn creetur' myself, and everythink that reminds me of creeturs that ain't lone and lorn, goes contrairy with me."

"Come, old gal!" cried Mr. Peggotty. "Take and heave it."

"No, Dan'l," returned Mrs. Gummidge, whimpering and shaking her head. "If I felt less, I could do more. You don't feel like me, Dan'l; thinks don't go contrairy with you, nor you with them; you had better do it yourself."

But here Peggotty, who had been going about from one to another in a hurried way, kissing everybody, called out from the cart, in which we were all by this time (Eml'y and I on two little chairs, side by side), that Mrs. Gurnmidge must do it. So Mrs. Gummiclge did it; and, I am sorry to relate, cast a damp upon the festive character of our departure by immediately bursting into tears and sinking subdued into the arms of Ham. . . .

Like the opening scene in the Blunderstone church and the school-room scene in the July 1849 installment, this scene situates David in a social and group setting; and yet once again he seems strangely aloof from the group in which he finds himself. The points of interest in the plate generally are not the scant details derived from the text—the figures in the scene; Barkis's drab pantaloons, buff waistcoat, and new blue coat with commodious cuffs; the one-horse chaise-cart; and the old shoe to be thrown after it—for these are givens that the author would have insisted upon once the author and graphic artist had selected the scene for illustration. Rather, the astute viewer focuses upon how Phiz extends the scene as Dickens describes it, a case in point being the chain, which is not mentioned in Dickens's description of the upside-down boathouse and its environs when David first visits the Peggottys in the third chapter, a locale which Phiz does not depict at that time and which the narrator describes merely as a "dull waste". Ham's gesturing with his left hand is ambiguous, for he may be drawing our attention to the shoe required by tradition or to the chain attached to the piling, which Phiz intends to be taken as symbolic of marriage generally, and perhaps even the fate of this particular marriage. In this respect, then, Ham acts on the artist's behalf as an internal commentator or Baroque spreker seen in the paintings of El Greco.

Although the narrator focuses upon Mr. Barkis' wedding suit and Mrs. Gummidge's hysterics when Daniel Peggotty has her throw the shoe, the artist provides the boathouse as the theatrical backdrop, its drying fishing nets lending the diminutive dwelling verisimilitude, for the outward action—Clara Peggotty's turning away from us to deliver parting words to her family as Mrs. Gummidge casts her gaze downward rather than regard the departing couple as Daniel and Ham (the familial resemblance obvious) joyfully watch her departure. As befits his rather one-dimensional character, Barkis is invested with little "inner life" beyond self-satisfaction. The subjects who attract the reader's attention by virtue of their "inner action" are Em'ly, self-contained and self-possessed in a costume that in every way reflects the bride's right down to the trim on the bonnet, and David, gazing philosophically at his surrogate brother, Ham, and surrogate father, Daniel Peggotty.

Ham, Mr. Peggotty, and Mrs. Gummidge

Chapter 10

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

The subject of this third illustration is the unconventional lowr middle-class family that provides its members — who are not even all blood relatives — mutual emotional support, a contrast in David's experience to his own dysfunctional, cold, repressive family of mother, stepfather, and aunt by marriage. The gentle, jovial Dan'l Peggotty and the jolly Ham Peggotty are in direct contrast to the cruel stepfather, Murdstone, and his cold, unfeeling sister, Jane Murdstone. Although the grouping might suggest any one of a number of moments in David's account of the Peggottys, an interchange on the facing page may be associated with the illustration:

Mrs. Gummidge moaned.

"Cheer up, mawther!" cried Mr. Peggotty.

"I feel it more than anybody else," said Mrs Gummidge. "I'm a lone lorn creetur', and she used to be a'most the only think that didn't go contrairy with me."

Unlike Phiz's illustrations, Eytinge's offer no context for the scene, which in fact occurs in the boathouse. Moreover, there is no caption pointing to a particular moment in the narrative, and no emblematic details to comment upon the situation and the character. Yet the faces and the postures of Eytinge's figures tell us much about their characters: Ham, naive but concerned; Dan'l, caring and optimistic; and Mrs. Gummidge, perpetually depressed and in need of comforting.

Peggotty and Barkis

Chapter 10

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

The most peculiar character in the first part of the story, the Yarmouth carrier, Barkis, is clearly interested in marrying Clara Peggotty, but somehow he lacks the self-confidence to propose for himself, and so he enlists the child upon whom Clara dotes to be his spokesman. Apparently — if we may judge by the rather formal manner in which the pair are dressed and the spatterboard of Barkis's wagon — they have just been married, and are driving away from the church:

She was a little confused when Mr. Barkis made this abrupt announcement of their union, and could not hug me enough in token of her unimpaired affection; but she soon became herself again, and said she was very glad it was over. Chp. 10

My magnificent order at the public house

Chapter 11

Phiz

Commentary:

The second illustration for the fourth monthly number, containing chapters 10, 11, and 12, conflates the David of the previous chapters, still wearing his uniform from Salem House, with the David bound over to the firm of Murdstone and Grinby, Blackfriars. David, like young Charles Dickens when his father was imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt, essentially descends from belonging to a number of families, namely his birth-family at Blunderstone, his adopted family of the Peggottys at Yarmouth, and the surrogate family of school boys at Salem House. In exchange for all of these, he becomes one of the workers in the bottling warehouse, associating with boys outside his class and experience. And yet, as the illustration set in the public house suggests in the costume worn by the protagonist, David remains himself. However, barely able to see over the bar at the gigantic figures of the benign publican and his wife and the enormous barrels above them. David is a diminutive and detached figure in an alien sphere trying very hard to belong. The passage illustrated by Phiz is one which Dickens actually adapted from his own fragmentary autobiography, "My Early Times," and so has an authentic quality in the narrative that is reinforced by the large forms and myriad details surrounding the three figures. The scene occurs after dinner, in a little public-house not far from the Thames:

I remember one hot evening I went into the bar of a public-house, and said to the landlord: "What is your best—your very best—ale a glass?" For it was a special occasion. I don't know what. It may have been my birthday.

"Twopence-halfpenny," says the landlord, "is the price of the Genuine Stunning ale."

"Then," says I, producing the money, "just draw me a glass of the Genuine Stunning, if you please, with a good head to it."

The landlord looked at me in return over the bar, from head to foot, with a strange smile on his face; and instead of drawing the beer, looked round the screen and said something to his wife. She came out from behind it, with her work in her hard, and joined him in surveying me. Here we stand, all three, before me now. The landlord in his shirt-sleeves, leaning against the bar window-frame; his wife looking over the little half-door; and I, in some confusion, looking up at them from outside the partition. They asked me a good marry questions; as, what my name was, how old I was, where I lived, how I was employed, and how I came there. To all of which, that I might not commit nobody, I invented, I am afraid, appropriate answers. They served me with the ale, though I suspect it was not the Genuine Stunning: and the landlord's wife, opening the little half-door of the bar, and bending down, gave me my money back, and gave me a kiss that was half admiring, and half compassionate, but all womanly and good, I am sure.

I know I do not exaggerate, unconsciously and unintentionally, the scantiness of my resources or the difficulties of life. I know that if a shilling were given me by Mr. Quinion at any time, I spent it in a dinner or a tea. I know, that I worked from morning until night, with common men and boys, a shabby child. I know that I lounged about the streets, insufficiently and unsatisfactorily fed.

Gareth Cordery in "Drink in David Copperfield" notes similarities between two of George Cruikshank's illustrations both entitled The Gin Shop (1829 and 1836) which (despite the very different underlying intentions of two artists' plates) suggest that Phiz here is responding as much to these earlier, pro-temperance images and that same artist's heavily moralistic "The Drunkard's Children" (1849) as he is to Dickens's 1849 text. As in the passage quoted, in the illustration David confidently orders an adult beverage, much to the amusement of the kindly pair of publicans behind the bar. Since David has probably just come from his menial work at the grimey warehouse, however, his costume in the plate (although not contradicted by the text) is at best improbable, and at worst a distortion intended to make the brazen order in a common drinking establishment seem more respectable. Cordery notes that Phiz has drawn the landlord not in his proletarian shirt-sleeves, as Dickens indicates, but in a middle-class jacket; his wife's tidy hair-do, white linen cap, shawl, and spotless apron reinforce this suggestion of middle-class affluence and respectability. Phiz, in other words, has transferred David from the common drinking establishment near the river to a middle-class emporium, complete with splendid gasolier (not unlike a fixture in the banquet chamber at the Prince Regent's Pavilion at Brighton in about the same period as this portion of the novel, the 1820s) and a Philpot's wine-list (left). Moreover, Phiz has eliminated the bar-window-frame and substituted a hinged portion of counter for the little half-door, so that the physical barrier between the boy and the adults is slight, just as their clothing proclaims them members of the same class. Whereas in the earlier plate "The Friendly Waiter and I" a timid David was being manipulated by an adult, here he self-conmfidently and nonchalantly indulges in a species of deception himself, trying to pass himself off as a member of the middle class rather than a common labouring boy from Murdstone and Grinby's warehouse. In that early plate, David was defined by the large maps and bills behind him as a mere child thrown too soon upon the wide world; here, Phiz presents David is a miniature adult, assertive and at ease in a thoroughly adult establishment, a variation on the infant Bacchus riding a cask and dangling a bunch of grapes in the pub's window, immediately above him.

His mother dead, expelled from Blunderstone Rookery, and away from the Peggotys [sic], David continues his search for surrogate parents,and here the amiable landlord and his good, compassionate wife, rejecting his role as the "little gent," offer themselves as just that, and the public house with the parlor door opening directly into the bar becomes, for a brief moment, a refuge and a home for the orphan boy.

Whereas the physically repulsive waiter had cheated David of his dinner and of his pint of ale, here the kindly publicans, thoroughly charmed by the plucky youngster, take a genuine interest him and even return his money to him. David is not served a "stunning" beverage, but only a weaker ale, in a shop that specializes not in the declasse gin, famously the subject of a Hogarthian satire "Gin Lane" (1751), but rather "Old Ale," "Soda Water," "Whiskey," and (in keeping with the image of Bacchus) "Nectar," the empty tankards (lower centre) and wine bottles (upper left) suggesting that only thoroughly respectable beverages are imbibed here under the comforting gazes of this pleasant couple whose good intentions toward the boy as well as their corpulence and middle-class status recall the Micawbers, with whom David boards.

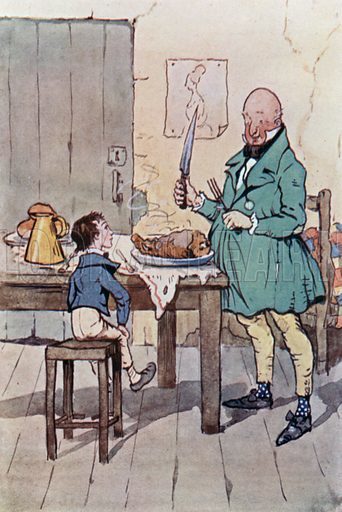

Mr. Micawber Conducts David Home

Chapter 11

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

The painful memories of his menial employment at Warren's Blacking Warehouse at Hungerford Stairs, Thames-side, Dickens sublimated into the scenes of his young protagonist's working at Murdstone and Grimby's wine-bottling facility at Blackfriars. Whereas the solitary young Dickens, his family in the Marshalsea Prison with his father, boarded in a rooming-house, after his mother's death David stays with the Micawber family, whose pater familias, Wilkins Micawber, one of the writer's greatest comic achievements, is in fact based on Dickens's childhood memories of his own father, the quixotic John Dickens. Having arrived in London and begun work, David meets singularly shabby-genteel "stoutish, middle-aged person, in a brown surtout and black tights and shoes, with no more hair upon his head . . . than there is upon an egg." This eventful meeting occurs in instalment four (chapter 11, "I Begin Life on My Own Account, and Don't Like It"), August 1849.

I begin life on my own account, and don't like it.

Chapter 11

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Murdstone and Grinby’s trade was among a good many kinds of people, but an important branch of it was the supply of wines and spirits to certain packet ships. I forget now where they chiefly went, but I think there were some among them that made voyages both to the East and West Indies. I know that a great many empty bottles were one of the consequences of this traffic, and that certain men and boys were employed to examine them against the light, and reject those that were flawed, and to rinse and wash them. When the empty bottles ran short, there were labels to be pasted on full ones, or corks to be fitted to them, or seals to be put upon the corks, or finished bottles to be packed in casks. All this work was my work, and of the boys employed upon it I was one.