The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Day of Battle

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

>

WE ARE OPEN - WEEK ONE - THE DAY OF BATTLE - January 12th ~ January 18th - PROLOGUE AND CHAPTER ONE ~ - Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason (1 - 46) No-Spoilers

All, we do not have to do citations regarding the book or the author being discussed during the book discussion on these discussion threads - nor do we have to cite any personage in the book being discussed while on the discussion threads related to this book.

However if we discuss folks outside the scope of the book or another book is cited which is not the book and author discussed then we do have to do that citation according to our citation rules. That makes it easier to not disrupt the discussion.

However if we discuss folks outside the scope of the book or another book is cited which is not the book and author discussed then we do have to do that citation according to our citation rules. That makes it easier to not disrupt the discussion.

Everyone, for the week of January 12th- January 18th, we are reading the Prologue and Part One-1.Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason.

The first week’s reading assignment is:

Week One - January 12th - January 18th

Prologue and Chapter One - Prologue and Part One-1 - 1. Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason - pages 1-46

Chapter Overview and Summary

Prologue

Chapter 1: Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason

The first week’s reading assignment is:

Week One - January 12th - January 18th

Prologue and Chapter One - Prologue and Part One-1 - 1. Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason - pages 1-46

Chapter Overview and Summary

Prologue

Chapter 1: Across the Middle Sea -Forcing the World Back to Reason

We are kicking off Book Two in the Trilogy - Welcome Everyone. Goodreads appears to have some bugs in the Event Notifications so I could not effectively get that out to you. I have notified goodreads but I have gotten no fixes as yet. We are working on that but in the meantime we are kicking off the discussion.

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 12, 2015 02:34PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

We hope that everyone will join us on this journey and if you have not completed the first book you can always go back but this book stands alone and can be read as focusing on The War in Sicily and Italy 1943-1944.

Here is an excerpt from Chapter One to pique your interest.

Chapter 1

The sun beat down on the stained white city, the July sun that hurt the eyes and turned the sea from wine-dark to silver. Soldiers crowded the shade beneath the vendors’ awnings and hugged the lee of the alabaster buildings spilling down to the port. Sweat darkened their collars and cuffs, particularly those of the combat troops wearing heavy herringbone twill. Some had stripped off their neckties, but kept them folded and tucked in their belts for quick retrieval. The commanding general had been spotted along the wharves, and every man knew that George S. Patton, Jr., would levy a $25 fine on any GI not wearing his helmet or tie.

Algiers seethed with soldiers after eight months of Allied occupation: Yanks and Brits, Kiwis and Gurkhas, swabs and tars and merchant mariners who at night walked with their pistols drawn against the bandits infesting the port. Troops swaggered down the boulevards and through the souks, whistling at girls on the balconies or pawing through shop displays in search of a few final souvenirs. Sailors in denim shirts and white caps mingled with French Senegalese in red fezzes, and bearded goums with their braided pigtails and striped burnooses. German prisoners sang “Erika” as they marched in column under guard to the Liberty ships that would haul them to camps in the New World. British veterans in battle dress answered with a ribald ditty called “El Alamein”—“Tally-ho, tally-ho, and that was as far as the bastards did go”—while the Americans belted out “Dirty Gertie from Bizerte,” which was said to have grown to two hundred verses, all of them salacious. “Sand in your shoes,” they called to one another—the North African equivalent of “Good luck”—and with knowing looks they flashed their index fingers to signal “I,” for “invasion.”

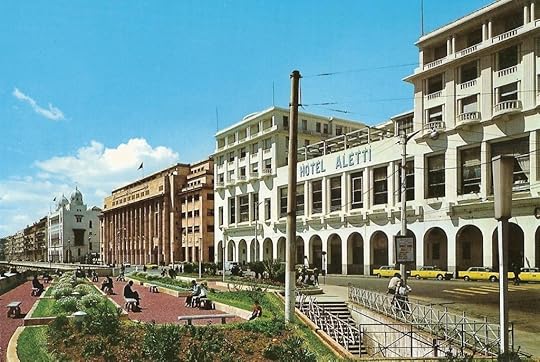

Electric streetcars clattered past horsedrawn wine wagons, to be passed in turn by whizzing jeeps. Speeding by Army drivers had become so widespread that military policemen now impounded offenders’ vehicles—although General Eisenhower had issued a blanket amnesty for staff cars “bearing the insignia of a general officer.” Most Algerians walked or resorted to bicycles, pushcarts, and, one witness recorded, “every conceivable variety of buggy, phaeton, carryall, cart, sulky, and landau.” Young Frenchmen strolled the avenues in their narrow-brimmed hats and frayed jackets. Arab boys scampered through the alleys in pantaloons made from stolen barracks bags, with two holes cut for their legs and the stenciled name and serial number of the former owner across the rump. Tatterdemalion beggars in veils wore robes tailored from old Army mattress covers, which also served as winding-sheets for the dead. The only women in Algiers wearing stockings were the hookers at the Hotel Aletti bar, reputed to be the richest wage-earners in the city despite the ban on prostitution issued by military authorities in May.

Above it all, at high noon on July 4, 1943, on the Rue Michelet in the city’s most fashionable neighborhood, a French military band tooted its way through the unfamiliar strains of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Behind the woodwinds and the tubas rose the lime-washed Moorish arches and crenellated tile roof of the Hôtel St. Georges, headquarters for Allied forces in North Africa. Palm fronds stirred in the courtyard, and the scent of bougainvillea carried on the light breeze.

Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt held his salute as the anthem dragged to a ragged finish. Eisenhower, also frozen in salute on Hewitt’s right, had discouraged all national celebrations as a distraction from the momentous work at hand, but the British had insisted on honoring their American cousins with a short ceremony. The last strains faded and the gunfire began. Across the flat roofs of the lower city and the magnificent crescent of Algiers Bay, Hewitt saw a gray puff rise from H.M.S. Maidstone, then heard the first report. Puff followed puff, boom followed boom, echoing against the hills, as the Maidstone fired seaward across the breakwater.

Nineteen, twenty, twenty-one. Hewitt lowered his salute, but the bombardment continued, and from the corner of his eye the admiral could see Eisenhower with his right hand still glued to his peaked khaki cap. Unlike the U.S. Navy, with its maximum twenty-one-gun tribute, the Army on Independence Day fired forty-eight guns, one for each state, a protocol now observed by Maidstone’s crew. Hewitt resumed his salute until the shooting stopped, and made note of yet another difference between the sister services.

With the ceremony at an end, Hewitt hurried through the courtyard and across the lobby’s mosaic floor to his office, down the corridor from Eisenhower’s corner suite. Every nook of the St. Georges was jammed with staff officers and communications equipment. Eight months earlier, on the eve of the invasion of North Africa, Allied plans had called for a maximum of seven hundred officers to man the Allied Forces Headquarters, or AFHQ, a number then decried by one commander as “two or three times too many.” Now the figure approached four thousand, including nearly two hundred colonels and generals; brigades of aides, clerks, cooks, and assorted horse-holders brought the AFHQ total to twelve thousand. The military messages pouring in and out of Algiers via seven undersea cables were equivalent to two-thirds of the total War Department communications traffic. No message was more momentous than the secret order issued this morning: “Carry out Operation husky.”

Hewitt had never been busier, not even before Operation torch, the assault on North Africa. Then he had commanded the naval task force ferrying Patton’s thirty thousand troops from Virginia to Morocco, a feat of such extraordinary success—not a man had been lost in the hazardous crossing—that Hewitt received his third star and command of the U.S. Navy’s Eighth Fleet in the Mediterranean. After four months at home, he had arrived in Algiers on March 15, and every waking moment since had been devoted to scheming how to again deposit Patton and his legions onto a hostile shore.

He was a fighting admiral who did not look the part, notwithstanding the Navy Cross on his summer whites, awarded for heroism as a destroyer captain in World War I. Sea duty made Hewitt plump, or plumper, and in Algiers he tried to stay fit by riding at dawn with native spahi cavalrymen, whose equestrian lineage dated to the fourteenth-century Ottomans. Despite these efforts, his frame remained, as one observer acknowledged, “well-upholstered.” At the age of fifty-six, the former altar boy and bell ringer from Hackensack, New Jersey, was still proud of his ability to ring out “Softly Now the Light of Day.” He loved double acrostic puzzles and his Keuffel & Esser Log Log Trig slide rule, a device that had been developed at the Naval Academy in the 1930s when he chaired the mathematics department there. His virtues, inconspicuous only to the inattentive, included a keen memory, a willingness to make decisions, and the ability to get along with George Patton. The Saturday Evening Post described Hewitt as “the kind of man who keeps a dog but does his barking himself”; in fact, he rarely even growled. He was measured and reserved, a good if inelegant conversationalist, and a bit pompous. He liked parties, and in Algiers he organized a Navy dance combo called the Scuttlebutt Five. He also had established a soup kitchen for the poor with leavings from Navy galleys; he ate the first bowl himself. Two other attributes served his country well: he was lucky, and he had an exceptional sense of direction, which on a ship’s bridge translated into a gift for navigation. Kent Hewitt always knew where he was.

He called for his staff car—among those privileged vehicles exempt from impoundment—and drove from the St. Georges through the twisting alleyways leading to the port. At every pier around the grand crescent of the bay, ships were moored two and three deep: freighters and frigates, tankers and transports, minesweepers and landing craft. Others rode at anchor beyond the harbor’s submarine nets, protected by patrol planes and destroyers tacking along the coastline. The U.S. Navy had thirty-three camouflage combinations, from “painted false bow wave” to “graded system with splotches,” and most seemed to be represented in the vivid Algiers anchorage. Stevedores swarmed across the decks; booms swung from dock to hold and back to dock again; gantry cranes hoisted pallet after pallet from the wharves onto the vessels. Precautions against fire were in force on every ship: wooden chairs, drapes, excess movie film, even bulkhead pictures had been removed; rags and blankets were ashore or well stowed; sailors—who upon departure would don long-sleeved undershirts as protection against flash burns—had chipped away all interior paint and stripped the linoleum from every mess deck.

Hewitt’s flagship, the attack transport U.S.S. Monrovia, lay moored on the port side of berth 39, on the Mole de Passageurs in the harbor’s Basin de Vieux. Scores of military policemen had boarded for added security, making her desperately overcrowded. Ten to twenty officers packed each cabin on many ships, with enlisted bunks stacked four high, and Monrovia was more jammed than most. With Hewitt’s staff, Patton’s staff, and her own crew, she now carried fourteen hundred men, more than double her normal company. She would also carry, in some of those cargo nets being manhandled into the hold, 200,000 rounds of high-explosive ammunition and 134 tons of gasoline.

The admiral climbed from his car and strode up the gangplank, greeted with a bosun’s piping and a flurry of salutes. Monrovia’s passageways seemed dim and cheerless after the brilliant African light. In the crowded operations room below, staff officers pored over “Naval Operations Order husky,” a tome four inches thick. Twenty typists had needed seven full days to bang out the final draft, of which eight hundred copies were distributed to commanders across North Africa as a blueprint for the coming campaign.

Hewitt could remember his father, a burly mechanical engineer, chinning himself with a hundred-pound dumbbell balanced across his feet. Sometimes the husky ops order felt like that dumbbell. Nothing was simple about the operation except the basic concept: in six days, on July 10, two armies—one American and one British—would land on the southeast coast of Sicily, reclaiming for the Allied cause the first significant acreage in Europe since the war began. An estimated 300,000 Axis troops defended the island, including a pair of capable German divisions, and many others lurked nearby on the Italian mainland.

More than three thousand Allied ships and boats, large and small, were gathering for the invasion from one end of the Mediterranean to the other—“the most gigantic fleet in the world’s history,” as Hewitt observed. About half would sail under his command from six ports in Algeria and Tunisia; the rest would sail with the British from Libya and Egypt, but for a Canadian division coming directly from Britain. Patton’s Seventh Army would land eighty thousand troops in the assault; the British Eighth Army would land about the same, with more legions subsequently reinforcing both armies.

Under the elaborate nautical choreography required, several convoys had already begun steaming: the vast expedition would rendezvous at sea, near Malta, on July 9.

Here is an excerpt from Chapter One to pique your interest.

Chapter 1

The sun beat down on the stained white city, the July sun that hurt the eyes and turned the sea from wine-dark to silver. Soldiers crowded the shade beneath the vendors’ awnings and hugged the lee of the alabaster buildings spilling down to the port. Sweat darkened their collars and cuffs, particularly those of the combat troops wearing heavy herringbone twill. Some had stripped off their neckties, but kept them folded and tucked in their belts for quick retrieval. The commanding general had been spotted along the wharves, and every man knew that George S. Patton, Jr., would levy a $25 fine on any GI not wearing his helmet or tie.

Algiers seethed with soldiers after eight months of Allied occupation: Yanks and Brits, Kiwis and Gurkhas, swabs and tars and merchant mariners who at night walked with their pistols drawn against the bandits infesting the port. Troops swaggered down the boulevards and through the souks, whistling at girls on the balconies or pawing through shop displays in search of a few final souvenirs. Sailors in denim shirts and white caps mingled with French Senegalese in red fezzes, and bearded goums with their braided pigtails and striped burnooses. German prisoners sang “Erika” as they marched in column under guard to the Liberty ships that would haul them to camps in the New World. British veterans in battle dress answered with a ribald ditty called “El Alamein”—“Tally-ho, tally-ho, and that was as far as the bastards did go”—while the Americans belted out “Dirty Gertie from Bizerte,” which was said to have grown to two hundred verses, all of them salacious. “Sand in your shoes,” they called to one another—the North African equivalent of “Good luck”—and with knowing looks they flashed their index fingers to signal “I,” for “invasion.”

Electric streetcars clattered past horsedrawn wine wagons, to be passed in turn by whizzing jeeps. Speeding by Army drivers had become so widespread that military policemen now impounded offenders’ vehicles—although General Eisenhower had issued a blanket amnesty for staff cars “bearing the insignia of a general officer.” Most Algerians walked or resorted to bicycles, pushcarts, and, one witness recorded, “every conceivable variety of buggy, phaeton, carryall, cart, sulky, and landau.” Young Frenchmen strolled the avenues in their narrow-brimmed hats and frayed jackets. Arab boys scampered through the alleys in pantaloons made from stolen barracks bags, with two holes cut for their legs and the stenciled name and serial number of the former owner across the rump. Tatterdemalion beggars in veils wore robes tailored from old Army mattress covers, which also served as winding-sheets for the dead. The only women in Algiers wearing stockings were the hookers at the Hotel Aletti bar, reputed to be the richest wage-earners in the city despite the ban on prostitution issued by military authorities in May.

Above it all, at high noon on July 4, 1943, on the Rue Michelet in the city’s most fashionable neighborhood, a French military band tooted its way through the unfamiliar strains of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Behind the woodwinds and the tubas rose the lime-washed Moorish arches and crenellated tile roof of the Hôtel St. Georges, headquarters for Allied forces in North Africa. Palm fronds stirred in the courtyard, and the scent of bougainvillea carried on the light breeze.

Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt held his salute as the anthem dragged to a ragged finish. Eisenhower, also frozen in salute on Hewitt’s right, had discouraged all national celebrations as a distraction from the momentous work at hand, but the British had insisted on honoring their American cousins with a short ceremony. The last strains faded and the gunfire began. Across the flat roofs of the lower city and the magnificent crescent of Algiers Bay, Hewitt saw a gray puff rise from H.M.S. Maidstone, then heard the first report. Puff followed puff, boom followed boom, echoing against the hills, as the Maidstone fired seaward across the breakwater.

Nineteen, twenty, twenty-one. Hewitt lowered his salute, but the bombardment continued, and from the corner of his eye the admiral could see Eisenhower with his right hand still glued to his peaked khaki cap. Unlike the U.S. Navy, with its maximum twenty-one-gun tribute, the Army on Independence Day fired forty-eight guns, one for each state, a protocol now observed by Maidstone’s crew. Hewitt resumed his salute until the shooting stopped, and made note of yet another difference between the sister services.

With the ceremony at an end, Hewitt hurried through the courtyard and across the lobby’s mosaic floor to his office, down the corridor from Eisenhower’s corner suite. Every nook of the St. Georges was jammed with staff officers and communications equipment. Eight months earlier, on the eve of the invasion of North Africa, Allied plans had called for a maximum of seven hundred officers to man the Allied Forces Headquarters, or AFHQ, a number then decried by one commander as “two or three times too many.” Now the figure approached four thousand, including nearly two hundred colonels and generals; brigades of aides, clerks, cooks, and assorted horse-holders brought the AFHQ total to twelve thousand. The military messages pouring in and out of Algiers via seven undersea cables were equivalent to two-thirds of the total War Department communications traffic. No message was more momentous than the secret order issued this morning: “Carry out Operation husky.”

Hewitt had never been busier, not even before Operation torch, the assault on North Africa. Then he had commanded the naval task force ferrying Patton’s thirty thousand troops from Virginia to Morocco, a feat of such extraordinary success—not a man had been lost in the hazardous crossing—that Hewitt received his third star and command of the U.S. Navy’s Eighth Fleet in the Mediterranean. After four months at home, he had arrived in Algiers on March 15, and every waking moment since had been devoted to scheming how to again deposit Patton and his legions onto a hostile shore.

He was a fighting admiral who did not look the part, notwithstanding the Navy Cross on his summer whites, awarded for heroism as a destroyer captain in World War I. Sea duty made Hewitt plump, or plumper, and in Algiers he tried to stay fit by riding at dawn with native spahi cavalrymen, whose equestrian lineage dated to the fourteenth-century Ottomans. Despite these efforts, his frame remained, as one observer acknowledged, “well-upholstered.” At the age of fifty-six, the former altar boy and bell ringer from Hackensack, New Jersey, was still proud of his ability to ring out “Softly Now the Light of Day.” He loved double acrostic puzzles and his Keuffel & Esser Log Log Trig slide rule, a device that had been developed at the Naval Academy in the 1930s when he chaired the mathematics department there. His virtues, inconspicuous only to the inattentive, included a keen memory, a willingness to make decisions, and the ability to get along with George Patton. The Saturday Evening Post described Hewitt as “the kind of man who keeps a dog but does his barking himself”; in fact, he rarely even growled. He was measured and reserved, a good if inelegant conversationalist, and a bit pompous. He liked parties, and in Algiers he organized a Navy dance combo called the Scuttlebutt Five. He also had established a soup kitchen for the poor with leavings from Navy galleys; he ate the first bowl himself. Two other attributes served his country well: he was lucky, and he had an exceptional sense of direction, which on a ship’s bridge translated into a gift for navigation. Kent Hewitt always knew where he was.

He called for his staff car—among those privileged vehicles exempt from impoundment—and drove from the St. Georges through the twisting alleyways leading to the port. At every pier around the grand crescent of the bay, ships were moored two and three deep: freighters and frigates, tankers and transports, minesweepers and landing craft. Others rode at anchor beyond the harbor’s submarine nets, protected by patrol planes and destroyers tacking along the coastline. The U.S. Navy had thirty-three camouflage combinations, from “painted false bow wave” to “graded system with splotches,” and most seemed to be represented in the vivid Algiers anchorage. Stevedores swarmed across the decks; booms swung from dock to hold and back to dock again; gantry cranes hoisted pallet after pallet from the wharves onto the vessels. Precautions against fire were in force on every ship: wooden chairs, drapes, excess movie film, even bulkhead pictures had been removed; rags and blankets were ashore or well stowed; sailors—who upon departure would don long-sleeved undershirts as protection against flash burns—had chipped away all interior paint and stripped the linoleum from every mess deck.

Hewitt’s flagship, the attack transport U.S.S. Monrovia, lay moored on the port side of berth 39, on the Mole de Passageurs in the harbor’s Basin de Vieux. Scores of military policemen had boarded for added security, making her desperately overcrowded. Ten to twenty officers packed each cabin on many ships, with enlisted bunks stacked four high, and Monrovia was more jammed than most. With Hewitt’s staff, Patton’s staff, and her own crew, she now carried fourteen hundred men, more than double her normal company. She would also carry, in some of those cargo nets being manhandled into the hold, 200,000 rounds of high-explosive ammunition and 134 tons of gasoline.

The admiral climbed from his car and strode up the gangplank, greeted with a bosun’s piping and a flurry of salutes. Monrovia’s passageways seemed dim and cheerless after the brilliant African light. In the crowded operations room below, staff officers pored over “Naval Operations Order husky,” a tome four inches thick. Twenty typists had needed seven full days to bang out the final draft, of which eight hundred copies were distributed to commanders across North Africa as a blueprint for the coming campaign.

Hewitt could remember his father, a burly mechanical engineer, chinning himself with a hundred-pound dumbbell balanced across his feet. Sometimes the husky ops order felt like that dumbbell. Nothing was simple about the operation except the basic concept: in six days, on July 10, two armies—one American and one British—would land on the southeast coast of Sicily, reclaiming for the Allied cause the first significant acreage in Europe since the war began. An estimated 300,000 Axis troops defended the island, including a pair of capable German divisions, and many others lurked nearby on the Italian mainland.

More than three thousand Allied ships and boats, large and small, were gathering for the invasion from one end of the Mediterranean to the other—“the most gigantic fleet in the world’s history,” as Hewitt observed. About half would sail under his command from six ports in Algeria and Tunisia; the rest would sail with the British from Libya and Egypt, but for a Canadian division coming directly from Britain. Patton’s Seventh Army would land eighty thousand troops in the assault; the British Eighth Army would land about the same, with more legions subsequently reinforcing both armies.

Under the elaborate nautical choreography required, several convoys had already begun steaming: the vast expedition would rendezvous at sea, near Malta, on July 9.

message 6:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 12, 2015 02:37PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter One - continued

A preliminary effort to capture the tiny fortified island of Pantelleria, sixty miles southwest of Sicily, had succeeded admirably: after a relentless three-week air bombardment, the stupefied garrison of eleven thousand Italian troops had surrendered on June 11, giving the Allies both a good airfield and the illusion that even the stoutest defenses could be reduced from the air.

A map of the Mediterranean stretched across a bulkhead in the operations room. Hewitt had become the U.S. Navy’s foremost amphibious expert, with one invasion behind him and another under way; three more were to come before war’s end. One inviolable rule in assaults from the open sea, he already recognized, was that the forces to be landed always exceeded the means to transport them, even with an armada as enormous as this one. From hard experience he also knew that two variables remained outside his control: the strength of the enemy defending the hostile shore and the caprice of the sea itself.

In husky, not only did he have three times more soldiers to put ashore than in Operation torch, he also commanded a flotilla of vessels seeing combat for the first time: nine new variations of landing craft and five new types of landing ship, including the promising LST, an abbreviation for “landing ship, tank,” but which sailors insisted meant “large slow target.” Some captains and crews had never been to sea before, and little was known about the seaworthiness of the new vessels, or how best to beach them, or what draught they would draw under various loads, or even how many troops and vehicles could be packed inside.

Much had been learned from the ragged, chaotic preparations for torch. Much had also been forgotten, or misapplied, or misplaced. The turmoil in North Africa in recent weeks seemed hardly less convulsive than that at Hampton Roads eight months earlier. Seven different directives on how to label overseas cargo had been issued the previous year; the resulting confusion led to formation of the inevitable committee, which led to another directive called the Schenectady Plan, which led to color-coded labels lacquered onto shipping containers, which led to more confusion. Five weeks after issuing a secret alert called Preparations for Movement by Water, the Army discovered that units crucial to husky had never received the order and thus had no plans for loading their troops, vehicles, and weapons onto the convoys. Seventh Army’s initial load plans also neglected to make room for the Army Air Forces, whose kit equaled a third of the Army’s total tonnage requirements. Every unit pleaded for more space; every unit claimed priority; every unit lamented the Navy’s insensitivity.

Despite the risk of German air raids, port lights burned all night as vexed loadmasters received still more manifest changes that required unloading another freighter or repacking another LST. Transportation officers wrestled with small oversights—the Navy had shipped bread ovens but no bread pans—and big blunders, as when ordnance officers mistakenly sent poisonous mustard gas to the Mediterranean. By the time Patton’s staff recognized that particular gaffe, on June 8, gas shells had been shipped with other artillery munitions; they now lay somewhere—no one knew precisely where—in the holds of one or more ships bound for Sicily.

Secrecy was paramount. Hewitt doubted that three thousand vessels could sneak up on Sicily, but husky’s success relied on surprise. All documents that disclosed the invasion destination were stamped with the classified code word bigot, and sentries at the husky planning headquarters in Algiers determined whether visitors held appropriate security clearances by asking if they were “bigoted.” (“I was frequently partisan,” one puzzled naval officer replied, “but had never considered my mind closed.”)

Soldiers and sailors, as usual, remained in the dark and subject to severe restrictions on their letters home. A satire of censorship regulations read to one ship’s crew included rule number 4—“You cannot say where you were, where you are going, what you have been doing, or what you expect to do”—and rule number 8—“You cannot, you must not, be interesting.” The men could, under rule number 2, “say you have been born, if you don’t say where or why.” And rule number 9 advised: “You can mention the fact that you would not mind seeing a girl.”

One airman tried to comply with the restrictions by writing, “Three days ago we were at X. Now we are at Y.” But the prevailing sentiment was best captured by a soldier who told his diary, “We know we are headed for trouble.”

More than half a million American troops now occupied North Africa. They composed only a fraction of all those wearing U.S. uniforms worldwide, yet in identity and creed they were emblematic of that larger force. One Navy lieutenant listed the civilian occupations of the fifteen hundred soldiers and sailors on his Sicily-bound ship: “farm boys and college graduates . . . lawyers, brewery distributors, millworkers, tool designers, upholsterers, steel workers, aircraft mechanics, foresters, journalists, sheriffs, cooks and glass workers.” One man even cited “horse mill fixer” as his trade.

Fewer than one in five were combat veterans from the four U.S. divisions that had fought extensively in Tunisia: the 1st, 9th, and 34th Infantry Divisions, and the 1st Armored Division, each of which was earmarked for Sicily or, later, for mainland Italy. “The front-line soldier I knew,” wrote the correspondent Ernie Pyle, who trudged with them across Tunisia, “had lived for months like an animal, and was a veteran in the fierce world of death. Everything was abnormal and unstable in his life.”

In the seven weeks since the Tunisian finale, those combat troops had tried to recuperate while preparing for another campaign. “The question of discipline has been very difficult,” the 1st Armored Division commander warned George Marshall. “There is a certain lawlessness . . . and a certain amount of disregard for consequences when men are about to go back.” In the 34th Division, “the men did not look well and seemed indifferent,” a visiting major general noted on June 15. Among other indignities, a thousand men had no underwear and five thousand others had but a single pair. “They felt very sorry for themselves,” he added. Thirteen hundred soldiers from the 34th had just been transferred to units headed straight for Sicily, leading to “incidents of self-maiming and desertion.” A captain in the 1st Division wrote home, “Too much self-commiseration, that is something we all must guard against.”

Even among the combat veterans, few considered themselves professional soldiers either by training or by temperament. Samuel Hynes, a fighter pilot who later became a university professor, described the prevalent “civilianness, the sense of the soldiering self as a kind of impostor.” They were young, of course—twenty-six, on average—and they shared a sense that “our youth had at last reached the place to spend itself,” in the words of a bomber pilot, John Muirhead.

They had been shoveled up in what Hynes called “our most democratic war, the only American war in which a universal draft really worked, [and] men from every social class went to fight.” Even the country’s most elite tabernacles had been dumped into a single egalitarian pot, the U.S. Army: of the 683 graduates from the Princeton University class of 1942, 84 percent were in uniform, and those serving as enlisted men included the valedictorian and salutatorian. Twenty-five classmates would die during the war, including nineteen killed in combat. “Everything in this world had stopped except war,” Pyle wrote, “and we were all men of a new profession out in a strange night.”

And what did they believe, these soldiers of the strange night? “Many men do not have a clear understanding of what they are fighting for,” a morale survey concluded in the summer of 1943, “and they do not know their role in the war.” Another survey showed that more than one-third had never heard of Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, and barely one in ten soldiers could name all four. In a secret letter to his commanders that July, Eisenhower lamented that “less than half the enlisted personnel questioned believed that they were more useful to the nation as soldiers than they would have been as war workers,” and less than one-third felt “ready and anxious to get into the fighting.” The winning entry in a “Why I’m Fighting” essay contest declared, in its entirety: “I was drafted.”

Their pervasive “civilianness” made them wary of martial zeal. “We were not romantics filled with cape-and-sword twaddle,” wrote John Mason Brown, a Navy Reserve lieutenant headed to Sicily. “The last war was too near for that.” Military life inflamed their ironic sensibilities and their skepticism. A single crude acronym that captured the soldier’s lowered expectations—SNAFU, for “situation normal, all fucked up”—had expanded into a vocabulary of GI cynicism: SUSFU (situation unchanged, still fucked up); SAFU (self-adjusting fuck-up); TARFU (things are really fucked up); FUMTU (fucked up more than usual); JANFU (joint Army-Navy fuck-up); JAAFU (joint Anglo-American fuck-up); FUAFUP (fucked up and fucked up proper); and FUBAR (fucked up beyond all recognition).

Yet they held personal convictions that were practical and profound. “We were prepared to make all sacrifices. There was nothing else for us to do,” Lieutenant Brown explained. “The leaving of our families was part of our loving them.” The combat artist George Biddle observed, “They want to win the war so they can get home, home, home, and never leave it.” A soldier in the 88th Division added, “We have got to lick those bastards in order to get out of the Army.”

The same surveys that worried Eisenhower revealed that the vast majority of troops held at least an inchoate belief that they were fighting to “guarantee democratic liberties to all peoples.” A reporter sailing to Sicily with the 45th Division concluded, “Many of the men on this ship believe that the operation will determine whether this war will end in a stalemate or whether it will be fought to a clear-cut decision.” And no one doubted that come the day of battle, they would fight to the death for the greatest cause: one another. “We did it because we could not bear the shame of being less than the man beside us,” John Muirhead wrote. “We fought because he fought; we died because he died.”

A later age would conflate them into a single, featureless demigod, possessed of mythical courage and fortitude, and animated by a determination to rebalance a wobbling world. Keith Douglas, a British officer who had fought in North Africa and would die at Normandy, described “a gentle obsolescent breed of heroes. . . . Unicorns, almost.” Yet it does them no disservice to recall their profound diversity in provenance and in character, or their feet of clay, or the mortality that would make them compelling long after their passing.

Captain George H. Revelle, Jr., of the 3rd Infantry Division, in a letter to his wife written while bound for Sicily, acknowledged “the chiselers, slackers, people who believe we are suckers for the munitions makers, and all the intellectual hodgepodge looking at war cynically.” In some measure, he wrote on July 7, he was “fighting for their right to be hypocrites.”

But there was also a broader reason, suffused with a melancholy nobility. “We little people,” Revelle told her, “must solve these catastrophes by mutual slaughter, and force the world back to reason.”

Copyright © 2007 by Rick Atkinson. All rights reserved.

http://liberationtrilogy.com/wp-conte...

You can listen to a sample audio file: (only four minutes worth)

http://liberationtrilogy.com/books/da...

A preliminary effort to capture the tiny fortified island of Pantelleria, sixty miles southwest of Sicily, had succeeded admirably: after a relentless three-week air bombardment, the stupefied garrison of eleven thousand Italian troops had surrendered on June 11, giving the Allies both a good airfield and the illusion that even the stoutest defenses could be reduced from the air.

A map of the Mediterranean stretched across a bulkhead in the operations room. Hewitt had become the U.S. Navy’s foremost amphibious expert, with one invasion behind him and another under way; three more were to come before war’s end. One inviolable rule in assaults from the open sea, he already recognized, was that the forces to be landed always exceeded the means to transport them, even with an armada as enormous as this one. From hard experience he also knew that two variables remained outside his control: the strength of the enemy defending the hostile shore and the caprice of the sea itself.

In husky, not only did he have three times more soldiers to put ashore than in Operation torch, he also commanded a flotilla of vessels seeing combat for the first time: nine new variations of landing craft and five new types of landing ship, including the promising LST, an abbreviation for “landing ship, tank,” but which sailors insisted meant “large slow target.” Some captains and crews had never been to sea before, and little was known about the seaworthiness of the new vessels, or how best to beach them, or what draught they would draw under various loads, or even how many troops and vehicles could be packed inside.

Much had been learned from the ragged, chaotic preparations for torch. Much had also been forgotten, or misapplied, or misplaced. The turmoil in North Africa in recent weeks seemed hardly less convulsive than that at Hampton Roads eight months earlier. Seven different directives on how to label overseas cargo had been issued the previous year; the resulting confusion led to formation of the inevitable committee, which led to another directive called the Schenectady Plan, which led to color-coded labels lacquered onto shipping containers, which led to more confusion. Five weeks after issuing a secret alert called Preparations for Movement by Water, the Army discovered that units crucial to husky had never received the order and thus had no plans for loading their troops, vehicles, and weapons onto the convoys. Seventh Army’s initial load plans also neglected to make room for the Army Air Forces, whose kit equaled a third of the Army’s total tonnage requirements. Every unit pleaded for more space; every unit claimed priority; every unit lamented the Navy’s insensitivity.

Despite the risk of German air raids, port lights burned all night as vexed loadmasters received still more manifest changes that required unloading another freighter or repacking another LST. Transportation officers wrestled with small oversights—the Navy had shipped bread ovens but no bread pans—and big blunders, as when ordnance officers mistakenly sent poisonous mustard gas to the Mediterranean. By the time Patton’s staff recognized that particular gaffe, on June 8, gas shells had been shipped with other artillery munitions; they now lay somewhere—no one knew precisely where—in the holds of one or more ships bound for Sicily.

Secrecy was paramount. Hewitt doubted that three thousand vessels could sneak up on Sicily, but husky’s success relied on surprise. All documents that disclosed the invasion destination were stamped with the classified code word bigot, and sentries at the husky planning headquarters in Algiers determined whether visitors held appropriate security clearances by asking if they were “bigoted.” (“I was frequently partisan,” one puzzled naval officer replied, “but had never considered my mind closed.”)

Soldiers and sailors, as usual, remained in the dark and subject to severe restrictions on their letters home. A satire of censorship regulations read to one ship’s crew included rule number 4—“You cannot say where you were, where you are going, what you have been doing, or what you expect to do”—and rule number 8—“You cannot, you must not, be interesting.” The men could, under rule number 2, “say you have been born, if you don’t say where or why.” And rule number 9 advised: “You can mention the fact that you would not mind seeing a girl.”

One airman tried to comply with the restrictions by writing, “Three days ago we were at X. Now we are at Y.” But the prevailing sentiment was best captured by a soldier who told his diary, “We know we are headed for trouble.”

More than half a million American troops now occupied North Africa. They composed only a fraction of all those wearing U.S. uniforms worldwide, yet in identity and creed they were emblematic of that larger force. One Navy lieutenant listed the civilian occupations of the fifteen hundred soldiers and sailors on his Sicily-bound ship: “farm boys and college graduates . . . lawyers, brewery distributors, millworkers, tool designers, upholsterers, steel workers, aircraft mechanics, foresters, journalists, sheriffs, cooks and glass workers.” One man even cited “horse mill fixer” as his trade.

Fewer than one in five were combat veterans from the four U.S. divisions that had fought extensively in Tunisia: the 1st, 9th, and 34th Infantry Divisions, and the 1st Armored Division, each of which was earmarked for Sicily or, later, for mainland Italy. “The front-line soldier I knew,” wrote the correspondent Ernie Pyle, who trudged with them across Tunisia, “had lived for months like an animal, and was a veteran in the fierce world of death. Everything was abnormal and unstable in his life.”

In the seven weeks since the Tunisian finale, those combat troops had tried to recuperate while preparing for another campaign. “The question of discipline has been very difficult,” the 1st Armored Division commander warned George Marshall. “There is a certain lawlessness . . . and a certain amount of disregard for consequences when men are about to go back.” In the 34th Division, “the men did not look well and seemed indifferent,” a visiting major general noted on June 15. Among other indignities, a thousand men had no underwear and five thousand others had but a single pair. “They felt very sorry for themselves,” he added. Thirteen hundred soldiers from the 34th had just been transferred to units headed straight for Sicily, leading to “incidents of self-maiming and desertion.” A captain in the 1st Division wrote home, “Too much self-commiseration, that is something we all must guard against.”

Even among the combat veterans, few considered themselves professional soldiers either by training or by temperament. Samuel Hynes, a fighter pilot who later became a university professor, described the prevalent “civilianness, the sense of the soldiering self as a kind of impostor.” They were young, of course—twenty-six, on average—and they shared a sense that “our youth had at last reached the place to spend itself,” in the words of a bomber pilot, John Muirhead.

They had been shoveled up in what Hynes called “our most democratic war, the only American war in which a universal draft really worked, [and] men from every social class went to fight.” Even the country’s most elite tabernacles had been dumped into a single egalitarian pot, the U.S. Army: of the 683 graduates from the Princeton University class of 1942, 84 percent were in uniform, and those serving as enlisted men included the valedictorian and salutatorian. Twenty-five classmates would die during the war, including nineteen killed in combat. “Everything in this world had stopped except war,” Pyle wrote, “and we were all men of a new profession out in a strange night.”

And what did they believe, these soldiers of the strange night? “Many men do not have a clear understanding of what they are fighting for,” a morale survey concluded in the summer of 1943, “and they do not know their role in the war.” Another survey showed that more than one-third had never heard of Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, and barely one in ten soldiers could name all four. In a secret letter to his commanders that July, Eisenhower lamented that “less than half the enlisted personnel questioned believed that they were more useful to the nation as soldiers than they would have been as war workers,” and less than one-third felt “ready and anxious to get into the fighting.” The winning entry in a “Why I’m Fighting” essay contest declared, in its entirety: “I was drafted.”

Their pervasive “civilianness” made them wary of martial zeal. “We were not romantics filled with cape-and-sword twaddle,” wrote John Mason Brown, a Navy Reserve lieutenant headed to Sicily. “The last war was too near for that.” Military life inflamed their ironic sensibilities and their skepticism. A single crude acronym that captured the soldier’s lowered expectations—SNAFU, for “situation normal, all fucked up”—had expanded into a vocabulary of GI cynicism: SUSFU (situation unchanged, still fucked up); SAFU (self-adjusting fuck-up); TARFU (things are really fucked up); FUMTU (fucked up more than usual); JANFU (joint Army-Navy fuck-up); JAAFU (joint Anglo-American fuck-up); FUAFUP (fucked up and fucked up proper); and FUBAR (fucked up beyond all recognition).

Yet they held personal convictions that were practical and profound. “We were prepared to make all sacrifices. There was nothing else for us to do,” Lieutenant Brown explained. “The leaving of our families was part of our loving them.” The combat artist George Biddle observed, “They want to win the war so they can get home, home, home, and never leave it.” A soldier in the 88th Division added, “We have got to lick those bastards in order to get out of the Army.”

The same surveys that worried Eisenhower revealed that the vast majority of troops held at least an inchoate belief that they were fighting to “guarantee democratic liberties to all peoples.” A reporter sailing to Sicily with the 45th Division concluded, “Many of the men on this ship believe that the operation will determine whether this war will end in a stalemate or whether it will be fought to a clear-cut decision.” And no one doubted that come the day of battle, they would fight to the death for the greatest cause: one another. “We did it because we could not bear the shame of being less than the man beside us,” John Muirhead wrote. “We fought because he fought; we died because he died.”

A later age would conflate them into a single, featureless demigod, possessed of mythical courage and fortitude, and animated by a determination to rebalance a wobbling world. Keith Douglas, a British officer who had fought in North Africa and would die at Normandy, described “a gentle obsolescent breed of heroes. . . . Unicorns, almost.” Yet it does them no disservice to recall their profound diversity in provenance and in character, or their feet of clay, or the mortality that would make them compelling long after their passing.

Captain George H. Revelle, Jr., of the 3rd Infantry Division, in a letter to his wife written while bound for Sicily, acknowledged “the chiselers, slackers, people who believe we are suckers for the munitions makers, and all the intellectual hodgepodge looking at war cynically.” In some measure, he wrote on July 7, he was “fighting for their right to be hypocrites.”

But there was also a broader reason, suffused with a melancholy nobility. “We little people,” Revelle told her, “must solve these catastrophes by mutual slaughter, and force the world back to reason.”

Copyright © 2007 by Rick Atkinson. All rights reserved.

http://liberationtrilogy.com/wp-conte...

You can listen to a sample audio file: (only four minutes worth)

http://liberationtrilogy.com/books/da...

Topics for Discussion:

We start out with an indication that George Patton was in charge and he was a tough man and Algiers was a tough environment. What are your first thoughts about the environment, the leaders, the soldiers and the era and what they were about to face?

We start out with an indication that George Patton was in charge and he was a tough man and Algiers was a tough environment. What are your first thoughts about the environment, the leaders, the soldiers and the era and what they were about to face?

What an interesting presentation.

What an interesting presentation. So interesting facts – pg 5 the Suez Canal saved two months on the England to India route

Pg 8 – 12% of the Brits (I assume of the total population) were in the service

Pg 31 para 3 – was my generation (born in 1944) the last to use slide rules?

Pg 35 – last para. – “our most democratic war…………a universal draft. – very interesting observation. – Is that part of why they could be called the “greatest generation”?

Hewitt – my hero in a second book. I do believe that engineers develop a discipline that helps to take on severe tasks and organize and succeed. (Would that I was one.) I wonder if there are any statues.

Atkinson presents the soldiers too – the “everybody” army. I guess the Brits had that too.

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 12, 2015 07:32PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Atkinson talks about what the songs the soldiers were singing - the Germans were singing Erika:

http://youtu.be/ATpi4duCA6k

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Heiß von hunderttausend kleinen Bienelein

wird umschwärmt Erika

denn ihr Herz ist voller Süßigkeit,

zarter Duft entströmt dem Blütenkleid.

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

Eagerly doted on by a hundred thousand little bees,

this Erika.

For her heart is full of sweetness,

a tender scent escapes her dress of blossoms.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

In der Heimat wohnt ein kleines Mägdelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Dieses Mädel ist mein treues Schätzelein

und mein Glück, Erika.

Wenn das Heidekraut rot-lila blüht,

singe ich zum Gruß ihr dieses Lied.

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Back at home, there lives a maiden

and she's called Erika.

That girl is my faithful little darling

and my happiness. Erika!

When the heather blooms in a reddish purple,

I sing her this song in greeting.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

In mein'm Kämmerlein blüht auch ein Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Schon beim Morgengrau'n sowie beim Dämmerschein

schaut's mich an, Erika.

Und dann ist es mir, als spräch' es laut:

"Denkst du auch an deine kleine Braut?"

In der Heimat weint um dich ein Mägdelein

und das heißt: Erika.

In my small chamber, there also blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

At dawn, it looks at me,

as does it at dusk. Erika!

And it is as if it spoke aloud:

"Don't you dare forget your little bride."

Back at home, a maiden weeps for you

and she's called Erika.

The Americans seemed to like this ribald ditty referred to by Atkinson.

http://arabkitsch.com/directory/dirty...

http://youtu.be/ATpi4duCA6k

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Heiß von hunderttausend kleinen Bienelein

wird umschwärmt Erika

denn ihr Herz ist voller Süßigkeit,

zarter Duft entströmt dem Blütenkleid.

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

Eagerly doted on by a hundred thousand little bees,

this Erika.

For her heart is full of sweetness,

a tender scent escapes her dress of blossoms.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

In der Heimat wohnt ein kleines Mägdelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Dieses Mädel ist mein treues Schätzelein

und mein Glück, Erika.

Wenn das Heidekraut rot-lila blüht,

singe ich zum Gruß ihr dieses Lied.

Auf der Heide blüht ein kleines Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Back at home, there lives a maiden

and she's called Erika.

That girl is my faithful little darling

and my happiness. Erika!

When the heather blooms in a reddish purple,

I sing her this song in greeting.

On the heath, there blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

In mein'm Kämmerlein blüht auch ein Blümelein

und das heißt: Erika.

Schon beim Morgengrau'n sowie beim Dämmerschein

schaut's mich an, Erika.

Und dann ist es mir, als spräch' es laut:

"Denkst du auch an deine kleine Braut?"

In der Heimat weint um dich ein Mägdelein

und das heißt: Erika.

In my small chamber, there also blooms a little flower

and it's called Erika.

At dawn, it looks at me,

as does it at dusk. Erika!

And it is as if it spoke aloud:

"Don't you dare forget your little bride."

Back at home, a maiden weeps for you

and she's called Erika.

The Americans seemed to like this ribald ditty referred to by Atkinson.

http://arabkitsch.com/directory/dirty...

Bentley wrote: "Topics for Discussion:

Bentley wrote: "Topics for Discussion:We start out with an indication that George Patton was in charge and he was a tough man and Algiers was a tough environment. What are your first thoughts about the environm..."

I still get the impression that the U.S. command and troops are still on the learning curve as we found in Book One. They seemed to be getting better, especially Hewitt and Patton were getting into a rhythm, but many mistakes for preparation for the invasion are being made.

by

by

Rick Atkinson

Rick Atkinson

I agree Bryan - the discipline seemed loose all around. Maybe that is why Patton appeared to be so draconian.

message 15:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 13, 2015 12:15PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Yes absolutely Scott - not terribly politically correct. Sometimes I think we have gone to the other extreme. Welcome Scott.

message 16:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 13, 2015 03:22PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Folks also feel free to start reading An Army at Dawn if you want to catch up at the same time while we are doing The Day of Battle.

All of the threads for An Army at Dawn are also in this folder. There is a Table of Contents and Syllabus thread for that too. And there are weekly threads, glossaries and bibliographies that you can refer to. Please note if you post on any of these threads to discuss this book - we will respond. So just jump right in wherever you are - We are here.

by

by

Rick Atkinson

Rick Atkinson

All of the threads for An Army at Dawn are also in this folder. There is a Table of Contents and Syllabus thread for that too. And there are weekly threads, glossaries and bibliographies that you can refer to. Please note if you post on any of these threads to discuss this book - we will respond. So just jump right in wherever you are - We are here.

by

by

Rick Atkinson

Rick Atkinson

Re: political correctness and "sensitivity training" - I don't think General Patton would've made it in today's army...but I like him.

Re: political correctness and "sensitivity training" - I don't think General Patton would've made it in today's army...but I like him.

Welcome Skeetor - probably not (lol) - but I always think they were men of their time and these are the men and the kind of men we needed then - just like the UK needed a Churchill.

Winston S. Churchill

Winston S. Churchill

Winston S. Churchill

Winston S. Churchill

Vince wrote: "Hewitt – my hero in a second book. I do believe that engineers develop a discipline that helps to take on severe tasks and organize and succeed. (Would that I was one.)..."

Vince wrote: "Hewitt – my hero in a second book. I do believe that engineers develop a discipline that helps to take on severe tasks and organize and succeed. (Would that I was one.)..."I'm impressed by Hewitt in this book, too. The more he does these invasions, the more valuable he becomes, quite an instrumental person.

I'm impressed by Atkinson's ability to drill down to the micro level at each moment. I wish, though, there were more "big picture" analyses, especially as to how the small moments relate to the overall war.

I'm impressed by Atkinson's ability to drill down to the micro level at each moment. I wish, though, there were more "big picture" analyses, especially as to how the small moments relate to the overall war. In the first book, we run into Rommel's army in Tunisia, because (it seems) Rommel has been chased out of Egypt and Libya by British troops on the other side in Egypt. But we don't get a lot of detail about Egypt because it's not part of "our" story.

Here, we are going into Sicily and Italy for a bunch of questionable reasons, but the one that seems most reasonable (to me, at least), is to appease Stalin, who is doing the lion's share of the fighting on the Eastern Front.

Is Stalin appeased? We don't know. He doesn't come to the meeting at the White House (or the earlier one in Casablanca. That sea to put him "outside the scope" and therefore unknowable. But it seems like there must have been some contact. Was Stalin content with American actions? Was he pushing for an invasion of the "soft underbelly"?

I wish we could get a few more big picture viewpoints to reflect the excellent drilling down on days and battles and moments.

Good point, Matthew, there is that limitation to the narrative. The war is a huge subject to cover, though, and Atkinson's trilogy does have a certain American focus to it.

Maybe the Allies thought Italy would be an easier victory than western Europe. Stalin certainly seemed to think so.

Maybe the Allies thought Italy would be an easier victory than western Europe. Stalin certainly seemed to think so.

I understand the need to focus, but the Egyptian campaign seemed inextricably part of the war in North Africa that we were reading about in An Army at Dawn. Was it a mistake to fight so hard in Egypt, with the result that Rommel was forced to retreat all the way to Tunisia, where he could turn around and fight on the other front? I don't know, because it wasn't discussed.

I understand the need to focus, but the Egyptian campaign seemed inextricably part of the war in North Africa that we were reading about in An Army at Dawn. Was it a mistake to fight so hard in Egypt, with the result that Rommel was forced to retreat all the way to Tunisia, where he could turn around and fight on the other front? I don't know, because it wasn't discussed. A running theme in the first book that carried over into Day of Battle is that the generals were still figuring things out and making beginner's mistakes. But there is no evidence that the British were screwing up Egypt and Libya the way they were Algeria and Tunisia. Better Generals? More experience? Longer history in the region? Same mistakes but we don't hear about them?

The Germans are being squeezed from both sides in Africa, and will start to be in Italy. My only complaint in what is so far excellent is just a few more pages discussing the other side of the Vice.

Bentley wrote: "Who are the Gurkhas?

Bentley wrote: "Who are the Gurkhas?http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-10782099"

So Gurkhas who are not UK citizens can join British Gurkha units?

Where are they stationed?

Does anyone know?

Thanks

Bentley wrote: "Welcome Skeetor - probably not (lol) - but I always think they were men of their time and these are the men and the kind of men we needed then - just like the UK needed a Churchill.

Bentley wrote: "Welcome Skeetor - probably not (lol) - but I always think they were men of their time and these are the men and the kind of men we needed then - just like the UK needed a Churchill.[authorimage:W..."

I think that both these fellows would have done well at most any time as long as they were raised into those times.

They both came from wealth.

Matthew wrote: "I understand the need to focus, but the Egyptian campaign seemed inextricably part of the war in North Africa that we were reading about in An Army at Dawn. Was it a mistake to fight so hard in Egy..."

Matthew wrote: "I understand the need to focus, but the Egyptian campaign seemed inextricably part of the war in North Africa that we were reading about in An Army at Dawn. Was it a mistake to fight so hard in Egy..."A fast observation about Rommel's strong effort to win in Egypt that Matthew mentioned. Rommel certainly must have feared US arrival and probably figured that to beat the Brits before the Americans arrived would have made holding North Africa more certain for the Germans (I think Rommel fought for the Germans not the Nazis)

message 26:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 14, 2015 11:30AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Vince wrote: "Bentley wrote: "Who are the Gurkhas?

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-10782099"

So Gurkhas who are not UK citizens can join British Gurkha units?

Where are they stationed?

Does anyone know?

Thanks"

Vince, some of your questions will be answered if you read message 11 and connect to the BBC link provided. - Interesting read.

Here is an extract from the link I provided in message 11:

"Following the partition of India in 1947, an agreement between Nepal, India and Britain meant four Gurkha regiments from the Indian army were transferred to the British Army, eventually becoming the Gurkha Brigade.

Since then, the Gurkhas have loyally fought for the British all over the world, receiving 13 Victoria Crosses between them.

More than 200,000 fought in the two world wars, and in the past 50 years they have served in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Borneo, Cyprus, the Falklands, Kosovo and now in Iraq and Afghanistan.

They serve in a variety of roles, mainly in the infantry but with significant numbers of engineers, logisticians and signals specialists.

The name "Gurkha" comes from the hill town of Gorkha from which the Nepalese kingdom had expanded.

The ranks have always been dominated by four ethnic groups, the Gurungs and Magars from central Nepal, the Rais and Limbus from the east, who live in villages of impoverished hill farmers.

They keep to their Nepalese customs and beliefs, and the brigade follows religious festivals such as Dashain, in which - in Nepal, not the UK - goats and buffaloes are sacrificed.

But their numbers have been sharply reduced from a World War II peak of 112,000 men, and now stand at about 3,500.

During the two world wars 43,000 men lost their lives.

The Gurkhas are now based at Shorncliffe near Folkestone, Kent - but they do not become British citizens.

The soldiers are still selected from young men living in the hills of Nepal - with about 28,000 youths tackling the selection procedure for just over 200 places each year.

The selection process has been described as one of the toughest in the world and is fiercely contested."

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-10782099"

So Gurkhas who are not UK citizens can join British Gurkha units?

Where are they stationed?

Does anyone know?

Thanks"

Vince, some of your questions will be answered if you read message 11 and connect to the BBC link provided. - Interesting read.

Here is an extract from the link I provided in message 11:

"Following the partition of India in 1947, an agreement between Nepal, India and Britain meant four Gurkha regiments from the Indian army were transferred to the British Army, eventually becoming the Gurkha Brigade.

Since then, the Gurkhas have loyally fought for the British all over the world, receiving 13 Victoria Crosses between them.

More than 200,000 fought in the two world wars, and in the past 50 years they have served in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Borneo, Cyprus, the Falklands, Kosovo and now in Iraq and Afghanistan.

They serve in a variety of roles, mainly in the infantry but with significant numbers of engineers, logisticians and signals specialists.

The name "Gurkha" comes from the hill town of Gorkha from which the Nepalese kingdom had expanded.

The ranks have always been dominated by four ethnic groups, the Gurungs and Magars from central Nepal, the Rais and Limbus from the east, who live in villages of impoverished hill farmers.

They keep to their Nepalese customs and beliefs, and the brigade follows religious festivals such as Dashain, in which - in Nepal, not the UK - goats and buffaloes are sacrificed.

But their numbers have been sharply reduced from a World War II peak of 112,000 men, and now stand at about 3,500.

During the two world wars 43,000 men lost their lives.

The Gurkhas are now based at Shorncliffe near Folkestone, Kent - but they do not become British citizens.

The soldiers are still selected from young men living in the hills of Nepal - with about 28,000 youths tackling the selection procedure for just over 200 places each year.

The selection process has been described as one of the toughest in the world and is fiercely contested."

Regarding the American landing in North Africa. My understanding is that two keys were a shorter supply line rather than just joining the British in Egypt. Also, a second supply line into the theater. The second key was that the American landing took what little air was left in the Vichy French sails out. After the landings and initial contact they really were not a threat for the rest of the war (if they ever were). I think there were also some political reasons for keeping American forces separate initially. It has been a long time since I read the initial book in the trilogy.

Regarding the American landing in North Africa. My understanding is that two keys were a shorter supply line rather than just joining the British in Egypt. Also, a second supply line into the theater. The second key was that the American landing took what little air was left in the Vichy French sails out. After the landings and initial contact they really were not a threat for the rest of the war (if they ever were). I think there were also some political reasons for keeping American forces separate initially. It has been a long time since I read the initial book in the trilogy. As stated above these things I mention are according to my own understandings.

I enjoyed reading the prologue and the first chapter. I am looking forward to the rest of the book. I was surprised that so many of the soldiers did "not have a clear understanding of what they were fighting for." (Chapter one, page 36) However, I was also impressed by their willingness to sacrifice for a cause that they did not fully understand.

I enjoyed reading the prologue and the first chapter. I am looking forward to the rest of the book. I was surprised that so many of the soldiers did "not have a clear understanding of what they were fighting for." (Chapter one, page 36) However, I was also impressed by their willingness to sacrifice for a cause that they did not fully understand.

Bentley wrote: "Vince wrote: "Bentley wrote: "Who are the Gurkhas?

Bentley wrote: "Vince wrote: "Bentley wrote: "Who are the Gurkhas?http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-10782099"

So Gurkhas who are not UK citizens can join British Gurkha units?

Where are they stationed?

Does anyone k..."

Thanks Bentley

The non British citizenship is interesting.

My only Gurkha experience is when I had one, retired for the military, with his dagger and a bandoleer of shotgun shells and a sawed off shotgun riding "shotgun" on a car drive in the Bihar province in India.

It was my most "adventurous" industrial tourism experience I think,

Vince

Im starting the Liberation Trilogy with book one tomorrow. Not to poke fun but the spoiler alert is funny, we do know how it all ends dont we?

Im starting the Liberation Trilogy with book one tomorrow. Not to poke fun but the spoiler alert is funny, we do know how it all ends dont we?

True but some folks do not want to know the details that are written by the author themselves - hence we have a non spoiler thread. (smile)

We are delighted to have you with us.

We are delighted to have you with us.

Thank you Bentley. Glad to be aboard. I always tell my friends that there were 60 million deaths in WW2 hence we have 60 million stories to learn of. Good reading guys and gals. THanks for having me on the group.

Thank you Bentley. Glad to be aboard. I always tell my friends that there were 60 million deaths in WW2 hence we have 60 million stories to learn of. Good reading guys and gals. THanks for having me on the group.

I like this passage about FDR and Churchill:

I like this passage about FDR and Churchill:"This was their true common language: the shared values of decency and dignity, of tolerance and respect. Despite the petty bickering and intellectual fencing, a fraternity bound them on the basis of who they were, what they believed, and why the fought." (p. 24, paperback)

Indeed, a good summation of their special relationship. Jon Meacham has a fairly good book on the subject:

by

by

Jon Meacham

Jon Meacham

by

by

Jon Meacham

Jon Meacham

message 39:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 17, 2015 07:22AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Bryan wrote: "I like this passage about FDR and Churchill:

"This was their true common language: the shared values of decency and dignity, of tolerance and respect. Despite the petty bickering and intellectual..."

Bryan I liked that quote too - you might want to add that to the quote thread as well - here is the link.

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Also, it is interesting to see Atkinson call out petty bickering - I would have thought it was more intellectual fencing - but Churchill was certainly jealous of the international relationships that FDR had with others. I think they were bound by their circumstances and that led to their extreme connection. In fact, Churchill and England were in a very tough spot and if it had not been for FDR defying his own Congress - who knows the fate that England might have faced. They had a rough time.

"This was their true common language: the shared values of decency and dignity, of tolerance and respect. Despite the petty bickering and intellectual..."

Bryan I liked that quote too - you might want to add that to the quote thread as well - here is the link.

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Also, it is interesting to see Atkinson call out petty bickering - I would have thought it was more intellectual fencing - but Churchill was certainly jealous of the international relationships that FDR had with others. I think they were bound by their circumstances and that led to their extreme connection. In fact, Churchill and England were in a very tough spot and if it had not been for FDR defying his own Congress - who knows the fate that England might have faced. They had a rough time.

Anyone know of a good primer where I can refer to whenever Atkinson refers to a specific "group" of soldiers" and I want to figure out what that means?

Anyone know of a good primer where I can refer to whenever Atkinson refers to a specific "group" of soldiers" and I want to figure out what that means?I went through the whole first book reading "The Allies sent II Corps, the imperturbable 1st Division, McQuillin, and CCB against Rommel's Afrika Korps, the Bersaglieri Battalion from Italy, and the 10th Panzer Division." So I had all the details, and no idea what it meant. Did the Allies have more troops but fewer tanks at the battle? Vice versa? How many people altogether?

I'm already feeling the same way about The Day of Battle. Lots of detail, but no sense of total numbers of Allies and Axis troops that will fight in Sicily.

message 42:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jan 18, 2015 12:14PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Interesting questions. A good thing to do with The Day of Battle is to go through the extensive glossaries for the Liberation Triology that we have added to along the way (Second World War) - there are three links provided in message one - there are a lot that have been added already. There probably is no one book Matthew but one open course that I recommend is the one from Harvard - here is the link - we had that posted in the Second World War folder which is also a source.

http://www.extension.harvard.edu/open...

Here is a Wikipedia source that lists numbers:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allied_i...

More:

http://www.history.army.mil/brochures...

http://www.bestofsicily.com/ww2.htm

http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?batt...

http://www.thehistoryreader.com/moder...

by

by

Andrew J. Birtle

Andrew J. Birtle

by

by

Carlo D'Este

Carlo D'Este

Also if you are looking for stats:

by John Ellis (no photo)

by John Ellis (no photo)

by

by

Peter Doyle

Peter Doyle

http://www.extension.harvard.edu/open...

Here is a Wikipedia source that lists numbers:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allied_i...

More:

http://www.history.army.mil/brochures...

http://www.bestofsicily.com/ww2.htm

http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?batt...

http://www.thehistoryreader.com/moder...

by

by

Andrew J. Birtle

Andrew J. Birtle by

by

Carlo D'Este

Carlo D'EsteAlso if you are looking for stats:

by John Ellis (no photo)

by John Ellis (no photo) by

by

Peter Doyle

Peter Doyle

Matthew wrote: "Anyone know of a good primer where I can refer to whenever Atkinson refers to a specific "group" of soldiers" and I want to figure out what that means?

Matthew wrote: "Anyone know of a good primer where I can refer to whenever Atkinson refers to a specific "group" of soldiers" and I want to figure out what that means?I went through the whole first book reading ..."

Hi Matthew, I have been reading about WW2 since I was in Jr. High. My dad fought with the 81st Wildcat Division against the Japanese. I feel your pain. I use google searches quite a bit if I am struggling with what an individual unit did or how they were made up. Part of the problem with knowing numbers as in how many men or tanks a unit had is that once battle was joined this changed and some units did not get back up to strength for a long time. Sometimes not even till the end of a campaign. There are reference books you can obtain that list various units as well. Order of battle is also made more tricky by various units being separated from parent units and given to different army groups on temporary duty. There are ways to figure out what you are looking for with a bit of study. Hope these comments help.

Thank you for the thoughts, Bentley and Michael. I think it is likely that it is not worthwhile to try to track down what the strength of a particular division, as it varies for engagement to engagement.

Thank you for the thoughts, Bentley and Michael. I think it is likely that it is not worthwhile to try to track down what the strength of a particular division, as it varies for engagement to engagement. What would be most useful would be for the author to do it himself. The themes I am picking up are that battles are won and lost based on the cunning and wisdom of the leaders. I just sometimes wish i had the numbers to back that up. I get the sense, though, that I will never read a passage where Atkinson says, "General Patton prepared a mediocre battle plan, but was victorious anyway because he had three times as many soldiers as the enemy."

You are welcome Matthew. One thing that we must remember to put into the equation is the commitment of the individual soldier. Some German units had to be totally annihilated in order to get through them while others melted away. Patton's tankers once opened fire on an enemy formation even though their tanks were out of fuel (what does it take to make that decision?) While we read the big picture it is important to realize that there are key moments in battle when an individual soldier's decision or example makes all the difference. Maneuver warfare was/is very complex.