The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

Dombey, Chapters 55 - 57

Chapters 56 and 57 and more conventional in that they deal with all sorts of happy endings: Uncle Sol returns, and it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him; Walter and Florence prepare for their marriage, which takes place - of course - in a much more modest church than that which has hitherto witnessed all the major events in the Dombey family's chronology; Susan and Polly are back again, and Toots comes to grips with his being just the best of friends for Florence instead of her bridegroom.

Chapters 56 and 57 and more conventional in that they deal with all sorts of happy endings: Uncle Sol returns, and it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him; Walter and Florence prepare for their marriage, which takes place - of course - in a much more modest church than that which has hitherto witnessed all the major events in the Dombey family's chronology; Susan and Polly are back again, and Toots comes to grips with his being just the best of friends for Florence instead of her bridegroom.Walter and Florence finally get married and go abroad and there is much heartrending farewell and yada yada.

What I enjoyed most in those two chapters was the little comical interlude about Miss Miff, the pew-opener, and Mr. Sownds, the beadle. There is some reference to Malthus and utilitarianism in Miss Miff's shaking her head about poor people's marriage plans (a bit like in The Chimes) and it is really very telling when Miss Miff says,

"''Drat 'em,[...] you read the same things over 'em and instead of sovereigns get sixpences!'"

I also cherished Dickens's metaphor in the following passage:

"She is such a spare, straight, dry old lady—such a pew of a woman—that you should find as many individual sympathies in a chip."

This is Dickens, likening the pew-opener to a pew with regard to the impersonal character of her public sentiments!

All I could think of during the impending train incident was "who brought up Russian literature in a previous thread?!".

All I could think of during the impending train incident was "who brought up Russian literature in a previous thread?!".The last part of this chapter was summed up perfectly by Tristram: Then the bitter and brutal end Carker has to face; absolutely breath-taking! My heart was definitely beating quickly as I sensed what was about to happen, didn't quite want it to (what a horrible death, even for such an evil man), but I couldn't tear my eyes away! Not only did Carker get plowed, but he had to catch the eye of the man he sabotaged. Anyway, I guess Carker did get his just deserts for his lifetime of nastiness.

These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings.

These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings. First, to Carker's death. He is drawn back to England, and even more specifically to board a train and escape to a quiet spot in the countryside. It is interesting to see how Dickens has worked the railroad into such a predominant symbol with in the novel. In much earlier chapters we read how the coming of the railroad brought massive change to the area in London known as Stagg's Gardens. Rob the Grinder's father was a railroad man and his mother Florence's wet nurse.

In the later chapters we see that the railroad has extended its tentacles to even the remote reaches of the countryside. How eerie is it when we reflect how Carker went to watch the trains in chapter 55. Later he sees Dombey, his pursuer, and Carker is killed by a train. As Tristram noted, this death is grotesque and gruesome... A fitting end to a vile man?

Tristram wrote: Chapter 55, which is sarcastically named "Rob the Grinder Loses His Place" (maybe to imply that no one is really unselfishly sad about the event described in the following;"

Tristram wrote: Chapter 55, which is sarcastically named "Rob the Grinder Loses His Place" (maybe to imply that no one is really unselfishly sad about the event described in the following;"I thought it was a clever way of disguising what actually happens in the chapter -- I thought that the chapter would be about Carker returning to England and Rob getting in trouble for having disclosed where Carker and Edith had gone.

Tristram wrote: "Dickens gives us keen psychological insight into the mind of the perpetrator. It's absolutely convincing that his self-confidence and brazenness are scattered because of the surprise Edith had in store for him. A deceived deceiver, he has completely lost his pluck and wants to lick his wounds first."

Tristram wrote: "Dickens gives us keen psychological insight into the mind of the perpetrator. It's absolutely convincing that his self-confidence and brazenness are scattered because of the surprise Edith had in store for him. A deceived deceiver, he has completely lost his pluck and wants to lick his wounds first."My response was somewhat different. I didn't think that Dickens gave anything like enough justification for Carker panicking as he did. What was there to be so afraid of? That Dombey would shoot him? He had apparently amassed plenty of money from his machinations, so he could have lived comfortably anywhere he chose to, he hasn't committed any crime and isn't wanted by the police. So Edith isn't interested in him, but okay, that may be a justification for anger, but not for that degree of panic and desperate flight. It didn't seem to me at all in character, or at all explained or justified.

Tristram wrote: "it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him."

Tristram wrote: "it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him."Is it really? Mrs MacStinger knew where he was. She was a responsible woman who cared for and about Captain Cuttle. Why wouldn't she have brought him the letters, or told the postman where to deliver them? That seems out of character for her, and to me a very weak point on Dickens's part.

In fact, generally I felt in these chapters that Dickens was losing his edge, that he wanted to get things over with and didn't care if he was making his characters (both Carker and Mrs. MacStinger) act in ways completely out of the characters he had established for them.

As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding.

As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding. Trite, trite, trite.

Chapters 56 and 57 demonstrate Dickens's ability to create balance within his writing. As horrid and bloody as Carker's death is at the end of chapter 55, Dickens begins chapter 56 "The Midshipman was alive." This chapter is alive with reunions, new beginnings, truths unveiled, gatherings and fellowship. While the previous chapter was one of gloom, foreboding, and isolation, chapter 56 is one bursting with people. As Carker was a lone, isolated, evil man, Florence is the opposite. In this chapter she is surrounded by those who love her or have returned to her. Captain Cuttle, Mr. Toots, Polly Richards, Walter, Sol Gill, Her former nurse Susan and even Diogenes crowd the stage of The Midshipman. One man died in chapter 55 and one man was left isolated and alone in the same chapter. Here, in chapters 56 and 57 we have love.

Chapters 56 and 57 demonstrate Dickens's ability to create balance within his writing. As horrid and bloody as Carker's death is at the end of chapter 55, Dickens begins chapter 56 "The Midshipman was alive." This chapter is alive with reunions, new beginnings, truths unveiled, gatherings and fellowship. While the previous chapter was one of gloom, foreboding, and isolation, chapter 56 is one bursting with people. As Carker was a lone, isolated, evil man, Florence is the opposite. In this chapter she is surrounded by those who love her or have returned to her. Captain Cuttle, Mr. Toots, Polly Richards, Walter, Sol Gill, Her former nurse Susan and even Diogenes crowd the stage of The Midshipman. One man died in chapter 55 and one man was left isolated and alone in the same chapter. Here, in chapters 56 and 57 we have love.Dickens writes that on their marriage morning "Florence and Walter, on their bridal morning, walk through the streets together." These are the same streets that once found Florence lost and alone and where her clothes were taken from her. The symbol of walking and shoes now returns to the reader. Walter had, years ago, kept one of Florence's shoes. Somewhat like an altered story of Cinderella, they now walk to church to marry. Their wealth is not as great as Dombey once had, or Carker aspired to obtain. Rather, their riches are that they have one another.

Thus the wealth Mr. Dombey had worked so hard to obtain, and Carker had aspired so hard to pervert, is found to be of no value at all. Florence and Walter have found their wealth in a place called the human heart.

Everyman wrote: "I thought it was a clever way of disguising what actually happens in the chapter -- I thought that the chapter would be about Carker returning to England and Rob getting in trouble for having disclosed where Carker and Edith had gone."

Everyman wrote: "I thought it was a clever way of disguising what actually happens in the chapter -- I thought that the chapter would be about Carker returning to England and Rob getting in trouble for having disclosed where Carker and Edith had gone."I agree. That's exactly what I thought was going to happen.

Everyman wrote: "As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding.

Everyman wrote: "As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding. Trite, trite, trite."

How long has Solomon been away? And to have him come back the very day before Walter's wedding, JUST in the nick of time. :)

Peter wrote: " While the previous chapter was one of gloom, foreboding, and isolation, chapter 56 is one bursting with people. "

Peter wrote: " While the previous chapter was one of gloom, foreboding, and isolation, chapter 56 is one bursting with people. "I like that way of looking at the chapters.

Peter wrote: "Thus the wealth Mr. Dombey had worked so hard to obtain, and Carker had aspired so hard to pervert, is found to be of no value at all. Florence and Walter have found their wealth in a place called the human heart. "

Peter wrote: "Thus the wealth Mr. Dombey had worked so hard to obtain, and Carker had aspired so hard to pervert, is found to be of no value at all. Florence and Walter have found their wealth in a place called the human heart. "Well, I'm not sure it's fair to say it is of no value at all, but the point is very nice that the only people who are happy (at this point) are those without much money, and the wealthy ones are not happy. But some of the poor folks are also not very happy (Mrs. Brown, for one!)

Everyman wrote: "I didn't think that Dickens gave anything like enough justification for Carker panicking as he did. What was there to be so afraid of? That Dombey would shoot him?"

Everyman wrote: "I didn't think that Dickens gave anything like enough justification for Carker panicking as he did. What was there to be so afraid of? That Dombey would shoot him?"Perhaps Carker has never been in a situation where he doesn't have everything thought out in advance? Where he doesn't have everyone under his thumb and knows just where everyone stands and what he holds over their heads? Now here he is in the heat of the moment just after having been refused by Edith, to his surprise, and then further surprised by the appearance of Dombey. Maybe he's great with playing chess and having all his moves and options set ahead of time, but this was one set of moves that he had not foreseen as a possibility.

Linda wrote: "Everyman wrote: "As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding.

Linda wrote: "Everyman wrote: "As expected, Solomon Gill has returned, safe and sound, just in time for Walter's wedding. Trite, trite, trite."

How long has Solomon been away? And to have him come back the ..."

Well... It is Dickens, so I guess last minute events, both good and bad, are all part of the package.

I have often wondered how frequently Dickens himself, with an eye roll and a bemused smile on his face, wondered "can I possibly write this and get away with it?"

... Perhaps best not to know...

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "it is also explained why Captain Cuttle has never received any letters from him."Is it really? Mrs MacStinger knew where he was... That seems out of character for her..."

Hmmm....I guess it does seem out of character for her. I wonder what Bunsby might have said to her after he escorted her home, never to return?

Chapter 39: Speechless and utterly amazed, the Captain saw him [Bunsby] gradually persuade this inexorable woman into the shop, return for rum and water and a candle, take them to her, and pacify her without appearing to utter one word. Presently he looked in with his pilot-coat on, and said, 'Cuttle, I'm a-going to act as convoy home;' and Captain Cuttle, more to his confusion than if he had been put in irons himself, for safe transport to Brig Place, saw the family pacifically filing off, with Mrs MacStinger at their head.

Although even this excerpt sounds like Bunsby might be sweet-talking to her and not threatening her to leave and not return.

I am wondering when we're going to get back to Dombey. He is, after all, the title character of the book, though I realize that it was serially written and Dickens had to settle on a title long before he knew exactly where the book was going to go. Still, Dombey seems to have been forgotten (except as a terror for Carker).

I am wondering when we're going to get back to Dombey. He is, after all, the title character of the book, though I realize that it was serially written and Dickens had to settle on a title long before he knew exactly where the book was going to go. Still, Dombey seems to have been forgotten (except as a terror for Carker). And will we ever find out what happens to Edith, who we left alone there in the hotel (or apartment building?), as far as we know with no money and no friend. I can't imagine that she would go back with Dombey, but if not that, what? I assume we'll find out, but can Dickens pull some sort of rabbit out of his hat to save both her character and her life?

Peter wrote: "I have often wondered how frequently Dickens himself, with an eye roll and a bemused smile on his face, wondered "can I possibly write this and get away with it?"

Peter wrote: "I have often wondered how frequently Dickens himself, with an eye roll and a bemused smile on his face, wondered "can I possibly write this and get away with it?"Ha! Now that's pretty funny, Peter. Of course now I will be wondering this exact same thought the next time something like this happens. :)

It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?

It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?I clearly got the impression that Carker was extremely envious of Florence and saw the need to control her, I guess to protect his own interests in the business. I kind of hoped that Florence might have had a direct influence in knocking him down a peg or two, before his gruesome demise. I feel like that part of the story was left at a loose end.

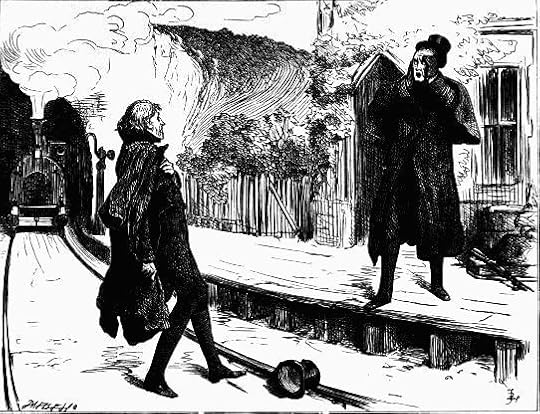

Extra illustration

Extra illustration

He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—

Chap. 55

Fred Barnard

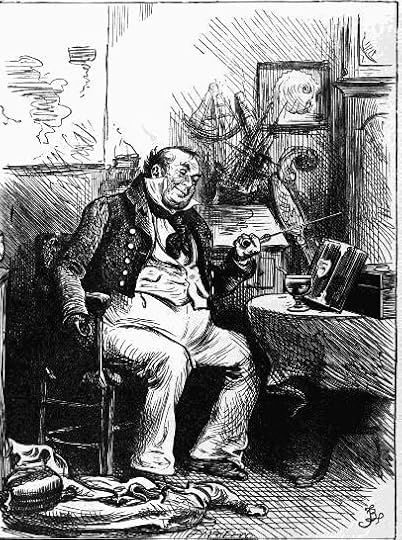

Extra illustration:

Extra illustration:

After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by himself, and was discovered chuckling at the expiration of as many hours—

Chapter 56

Fred Barnard

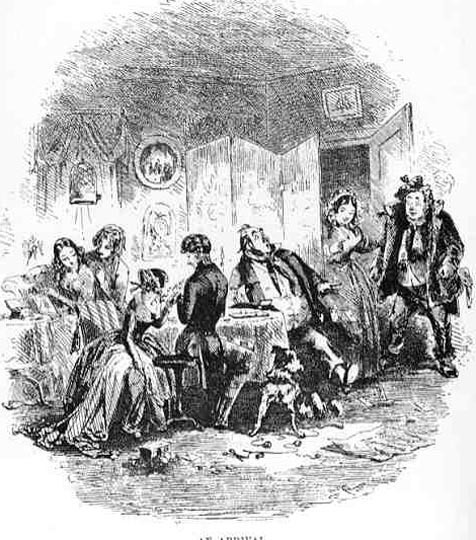

The parting of Mr. Toots and the game Chicken by Fred Barnard:

The parting of Mr. Toots and the game Chicken by Fred Barnard:

"Wy, it's mean . . . . that's where it is. It's mean!"—

Chapter 56

Fred Barnard

Kim wrote: "Extra illustration:

Kim wrote: "Extra illustration:After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by himself, and was discovered chuckling at the expiration of as many hours—

Chapter 56

Fred Barnard"

Now this illustration captures what I think Captain Cuttle would be like, and I am not "kyding."

Kate wrote: "It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?

Kate wrote: "It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?I clearly got the impression that Carker was extremely envious of ..."

Hi Kate

I certainly agree that Carker strongly disliked Florence ( and, seemingly, everyone else) and that by being a Dombey she certainly would have been at the top of his hate list.

I wonder if Dickens wanted to separate Florence from Carker's gruesome end to keep Florence's angelic character as intact as possible. Also, since Edith was the character who began Carker's final rapid downward spiral, perhaps Dickens saw Edith as acting somewhat as Florence's literary proxy. In that way the reader gains more respect for Edith's actions against Carker, and thus towards her final act of defending Florence.

Peter wrote: "Kate wrote: "It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?

Peter wrote: "Kate wrote: "It is just me or did you find Dickens was building up to something more, perhaps like a 'stand off', between Carker and Florence?I clearly got the impression that Carker was extremel..."

Yes, very true Peter. Although I feel Edith has unfairly bared the brunt of it all. I won't say too much more as I have finished the book and don't want to give away any spoilers, but I guess, as usual, we have to expect the angelic to remain so through Dickens' extreme romanticising.

Peter wrote: "Now this illustration captures what I think Captain Cuttle would be like, and I am not "kyding."

Peter wrote: "Now this illustration captures what I think Captain Cuttle would be like, and I am not "kyding." Ah, speaking of Kyd, here's what he thought of the Game Chicken:

Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings.

Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings. First, to Carker's death. He is drawn back to England, and even more specif..."

The more I think about the symbolic meaning of the railroad the less convinced I am by Dickens's decision in having a train bring down Carker. Whenever the railroad appeared in previous chapters, it seemed to be a symbol of change, of modern times, and also of the ruthlessly normative power of the actual, of business, commerce and the absence of sentimentality of any kind. Dickens presents it as a ruthless and monstrous force.

And yet it kills off Carker, who, to some degree, can also be seen as a representative of some of these ideas, e.g. unfettered egoism.

I don't quite get it.

Kim wrote: "And here is what he thought of Solomon Gills:

Kim wrote: "And here is what he thought of Solomon Gills:"

Keep them coming. Did Kyd illustrate any other Dickens novels? I think I hear the groans already ... ; -)

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now this illustration captures what I think Captain Cuttle would be like, and I am not "kyding."

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now this illustration captures what I think Captain Cuttle would be like, and I am not "kyding." Ah, speaking of Kyd, here's what he thought of the Game Chicken:

"

Here I spot some resemblence between the figure in the drawing and the character in the book although I'd have imagined the Game Chicken more stocky and compact.

Everyman wrote: "My response was somewhat different. I didn't think that Dickens gave anything like enough justification for Carker panicking as he did. What was there to be so afraid of? That Dombey would shoot him? He had apparently amassed plenty of money from his machinations, so he could have lived comfortably anywhere he chose to, he hasn't committed any crime and isn't wanted by the police. So Edith isn't interested in him, but okay, that may be a justification for anger, but not for that degree of panic and desperate flight. It didn't seem to me at all in character, or at all explained or justified.

Everyman wrote: "My response was somewhat different. I didn't think that Dickens gave anything like enough justification for Carker panicking as he did. What was there to be so afraid of? That Dombey would shoot him? He had apparently amassed plenty of money from his machinations, so he could have lived comfortably anywhere he chose to, he hasn't committed any crime and isn't wanted by the police. So Edith isn't interested in him, but okay, that may be a justification for anger, but not for that degree of panic and desperate flight. It didn't seem to me at all in character, or at all explained or justified."

I see your point, Everyman, in that a scheming scoundrel like Carker, whose underhanded trickery has not even induced him to do anything illegal so that he won't have to fear the police, might not see any reason to flee.

However, I'd agree with Linda that a villain like him, who is so cocksure of himself and used to all his manipulations being successful, who plans every single step in advance and has never had any occasion to see any of his schemes thwarted, who creeps into the psyche of his victims, sensing their weakness and knowing whichever lever to pull, that such a man, in short, at finding himself the dupe of one whom he himself intended to be his dupe might lose his nerve at this experience, all the more so as he was evidently interested in making Edith his mistress.

I cannot help it, but this seems very convincing to me.

Everyman wrote: "Is it really? Mrs MacStinger knew where he was. She was a responsible woman who cared for and about Captain Cuttle. Why wouldn't she have brought him the letters, or told the postman where to deliver them? That seems out of character for her, and to me a very weak point on Dickens's part.

Everyman wrote: "Is it really? Mrs MacStinger knew where he was. She was a responsible woman who cared for and about Captain Cuttle. Why wouldn't she have brought him the letters, or told the postman where to deliver them? That seems out of character for her, and to me a very weak point on Dickens's part.In fact, generally I felt in these chapters that Dickens was losing his edge, that he wanted to get things over with and didn't care if he was making his characters (both Carker and Mrs. MacStinger) act in ways completely out of the characters he had established for them. "

I agree with you here: Mrs. Mac Stinger is such a responsible and honourable woman that it would seem unlikely for her to withhold the letters out of spite. Before Sol mentioned that he had addressed all the letters to Captain Cuttle's place, I assumed that they would have gone to the Midshipman where they would have been intercepted by Rob the Grinder at Carker's behest.

Nevertheless, before stamps were introduced (in the early 1840s, if I'm not wrong), the person who was about to receive the letter had to pay for the delivery and not the person who sent it. If the addressee objected to paying, the letter would have been taken away again.

Maybe Mrs. Mac Stinger is such a thrifty woman that, with the Captain gone and she not sure if she would ever trace him, simply refused to pay for the letters, who came from a man totally unknown to her. We should neither forget that Mrs. Mac Stinger will probably also have felt betrayed and hurt by the Captain's absconding, which will probably not have increased her tendency to lay down money for letters that might never be opened, anyway, and that were no business of hers.

A weak explanation, I know, but I thought I'd just throw it into the discussion.

Everyman wrote: "I like that way of looking at the chapters. "

Everyman wrote: "I like that way of looking at the chapters. "So do I, and I think Peter showed very clearly how nicely the chapters are counterbalanced with regard to their topics and motifs.

Add to this Dickens's need to consider that he was writing in monthly instalments and that he

a) could not afford to lose sight of any of his characters or a particular subplot for too long as otherwise people would simply not remember them very well,

b) would have had to introduce some sort of cliff-hanger from time to time to ensure that his audience would not wane away,

and then you can imagine how difficult it must have been for him to plan his novels (the later ones, especially that were planned carefully in advance) with regard to their form of publication.

The earlier novels still bear lots of signs of these difficulties, e.g. a lack of balance, arbitrary plot-changes, characters just occurring out of nowhere (Sam Weller) and simply fading away (Little Nell's brother), but the later novels - and here I would include Dombey and Son - are carefully and artfully constructed.

About Carker, Edith and Florence

About Carker, Edith and FlorencePeter's idea of Edith acting as Florence's "literary proxy" - a fine expression, I'd say - is quite intriguing. For a start, Florence is obviously meant to be seen as the ideal of Victorian womanhood: self-sacrificing, loving, caring, forbearing and still endowed with a certain firmness when it comes to helping others, like her brother, but not in the face of others. Such a more self-confident, aggressive streak in her character would not have gone down well.

And that is why Edith comes into play, who is more than just a match for Carker.

I remember the passage (although I do no longer recollect where to find it) when Carker stands musing in front of the Dombey mansion looking up to Edith's window and later turning to Florence's, saying something like, "There was a time when it was well worth my while watching your star rise" or something like that. Since the novel is more carefully planned than any Dickens novel before, it is hard to believe that Dickens might have changed his ideas as to the development of the plot mid-way. Instead I think that the Carker-Florence situation in the first half of the novel was a means of creating suspense but also of making the reader aware of the menacing quality of Carker. Carker soon shifts his malevolent (and "amorous"?) intentions from Florence to Edith because he thinks Edith's star more promising than Florence's, who is obviously not much of a favourite with her father. In literary terms, however, this shift of attention may have been brought about by Dickens's feeling that the Florence concept would not include the pluck, the aggressiveness and the cleverness to stand up against Carker.

Tristram wrote: "And yet it kills off Carker, who, to some degree, can also be seen as a representative of some of these ideas, e.g. unfettered egoism."

Tristram wrote: "And yet it kills off Carker, who, to some degree, can also be seen as a representative of some of these ideas, e.g. unfettered egoism."Those who live by the sword...

Peter wrote: " Did Kyd illustrate any other Dickens novels? I think I hear the groans already

Peter wrote: " Did Kyd illustrate any other Dickens novels? I think I hear the groans alreadyMore than groans. Cries of outright agony.

I am sure that Kyd was simply living up to his name. Every illustration he did, he was totally kydding.

Tristram wrote: "... such a man, in short, at finding himself the dupe of one whom he himself intended to be his dupe might lose his nerve at this experience, all the more so as he was evidently interested in making Edith his mistress..."

Tristram wrote: "... such a man, in short, at finding himself the dupe of one whom he himself intended to be his dupe might lose his nerve at this experience, all the more so as he was evidently interested in making Edith his mistress..."I can see anger, loss of self-esteem, even despair, giving in to funk, withdrawing. I can see him committing murder, or even perhaps suicide. But flight? And desperate, panicked flight at that? Why? That's not a response that makes any sense to me given the situation.

Tristram wrote: "Maybe Mrs. Mac Stinger is such a thrifty woman that, with the Captain gone and she not sure if she would ever trace him, simply refused to pay for the letters, who came from a man totally unknown to her.."

Tristram wrote: "Maybe Mrs. Mac Stinger is such a thrifty woman that, with the Captain gone and she not sure if she would ever trace him, simply refused to pay for the letters, who came from a man totally unknown to her.."That's possible, but why wouldn't she at least tell the postman where Cuttle was so he could deliver them? She knew, and could easily have done that.

Letters at the time were pretty significant things. I don't see a responsible woman just tossing them away or sending them back without any attempt to see them delivered.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: " Did Kyd illustrate any other Dickens novels? I think I hear the groans already

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: " Did Kyd illustrate any other Dickens novels? I think I hear the groans alreadyMore than groans. Cries of outright agony.

I am sure that Kyd was simply living up to his name. Eve..."

Touche

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings. First, to Carker's death. He is drawn back to England, and ev..."

Good points. The railroad is certainly used as a symbol in the novel, and Carker seems fascinated by its presence, even in rural areas, and he meets a gruesome death because of a train. The meaning/symbolism of Carker's death-by-train is not clear to me either.

Here are a few guesses.

(1) The firm of Dombey and Son also deals with transportation, but transportation by sea. I'm not sure where to go with this thought since there are no railroads across the Atlantic, but could it have to do, somehow, with the changing of modes of transportation, times to move goods by transportation, or the unwillingness to adapt to the times. This idea seems somewhat weak.

(2) The presence of the railroad did mark a monumental shift in the transport of both goods and people. It was a relatively recent phenomenon (say about 20 years or so) and it did allow even the lower classes greater mobility within England. There were numerous problems, disasters and even deaths frequently associated with the railway and so its presence and its potential for disaster would have been quite well known to the population. Perhaps Dickens used the death of Carker by a train as a familiar touchstone to the knowledge and understanding of the reading public. As, sadly, we have experienced airplane tragedies this past year that strike our collective conscious, so a train death would resonate with the Victorian reading public. A great event to unfold in Dickens's own personal future with a train derailment almost taking his life was yet to come.

(3) Perhaps the answer resides in the simplicity of a gruesome death for a loathsome character. Just as Sikes and Quilp, evil men both, must die a very dramatic and unpleasant death because of their deeds, so too must Carker follow them in a very dramatic, and fittingly Dickensian manner. I'm sure the reading public wanted some horrid end, and Dickens obliged the public's desire.

Peter wrote: "The meaning/symbolism of Carker's death-by-train is not clear to me either.

Peter wrote: "The meaning/symbolism of Carker's death-by-train is not clear to me either.Here are a few guesses."

Great guesses, Peter! You've done a lot more thinking on why Death by Train had to be Carker's end than I have. I just thought it was a fitting end for a horrid man, so I guess I would place myself under option (3).

But I am intrigued by option (2) also. Perhaps a combination of (2) and (3) makes for an even more forceful impact upon Dickens' readers?

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "The meaning/symbolism of Carker's death-by-train is not clear to me either.

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "The meaning/symbolism of Carker's death-by-train is not clear to me either.Here are a few guesses."

Great guesses, Peter! You've done a lot more thinking on why Death by Train had..."

Hi Linda

I also think a combination of 2 and 3 is correct. It would be interesting to know if in his journal publications he was writing about trains/train disasters about this time or if a train disaster had occurred just before the publication of this part of the novel. In that way, he would be able to piggyback a story from the newspapers onto his own novel.

Everyman wrote: "That's possible, but why wouldn't she at least tell the postman where Cuttle was so he could deliver them? She knew, and could easily have done that. "

Everyman wrote: "That's possible, but why wouldn't she at least tell the postman where Cuttle was so he could deliver them? She knew, and could easily have done that. "At first, Mrs. Mac Stinger did not know where the Captain had gone, and he took any care he was capable of to make sure that this would last. Later, when she knew where he was staying, maybe she was so indignant at the Captain that she simply didn't want to have anything to do with him anymore. She sent him his things, and she might just have forgotten that there was the odd letter delivery from time to time.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "These chapters provide so much; we have drama, excitement, partings and death as well as reunions and new beginnings. First, to Carker's death. He is drawn back t..."

Like Linda, I would also suggest that theories 2 and 3 are the most convincing ones. As to 1, modernizing his business by making use of the railroad was not much of an option for Dombey as he was an overseas merchant. So I think the railway's symbolism in implying that Dombey's business was no longer up-to-date would not have gone very far.

Gruesome deaths for nasty people as a kind of poetic justice is probably the key. We remember Ralph Nickleby's lonesome and desperate suicide, Bill Sikes's inadvertent hanging, Fagin's execution and the hours of anxiety he underwent before it, then Quilp and Jonas Chuzzlewit, who also takes his own life. Poetic justice is quite hypocritical in a way in that it allows the reader the satisfaction of having their own desire for revenge presented as a act of fate or something similar. But it also works with me as I do expect a gruesome death to lie in store for the villain of a story.

Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."

Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."I thought of you, Joy, when Uncle Sol walked in the door. "A-ha! Joy's speculation was wrong!" :)

Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."

Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."And yes, there are a few chapters left still. If Uncle Sol ends up getting hit by a train by accident, we are going to have to rethink Peter's Death by Train theories.

Linda wrote: "Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."

Linda wrote: "Joy wrote: "Also, Hooray, Uncle Sol lives. There are a few chapters left but I'm pretty sure he is safe now."And yes, there are a few chapters left still. If Uncle Sol ends up getting hit by a t..."

Actually, Linda, if Old Sol got hit by a train, everything would be fine with me because I thought that the railway is a symbol of progress and change in the novel, and we all know that Old Sol was hopelessly old-fashioned.

we're now coming close to the ending of our much-appreciated Dombey and Son, and we see how Dickens ties up some of his plotlines.

Chapter 55, which is sarcastically named "Rob the Grinder Loses His Place" (maybe to imply that no one is really unselfishly sad about the event described in the following; although with the probable exception of Carker's siblings), tells us about Carker's flight from the scene of his humiliation and finally about his being crushed by a train.

Of course, one can exchange a lot of ideas on why it is a train that killed Carker, and why Carker, in his felon's despondency seems to have been so fatefully attracted to the locomotives.

I am very impressed by Dickens's language again, by his ability to let us feel the strange mix of monotony and tension that must have been characteristic to Carker's state of mind during his flight. Apart from that, Dickens gives us keen psychological insight into the mind of the perpetrator. It's absolutely convincing that his self-confidence and brazenness are scattered because of the surprise Edith had in store for him. A deceived deceiver, he has completely lost his pluck and wants to lick his wounds first.

Then Dickens's hint at some possible streak of light in Carker's character:

"The air struck chill and comfortless as it breathed upon him. There was a heavy dew; and, hot as he was, it made him shiver. After a glance at the place where he had walked last night, and at the signal-lights burning in the morning, and bereft of their significance, he turned to where the sun was rising, and beheld it, in its glory, as it broke upon the scene.

So awful, so transcendent in its beauty, so divinely solemn. As he cast his faded eyes upon it, where it rose, tranquil and serene, unmoved by all the wrong and wickedness on which its beams had shone since the beginning of the world, who shall say that some weak sense of virtue upon Earth, and its in Heaven, did not manifest itself, even to him? If ever he remembered sister or brother with a touch of tenderness and remorse, who shall say it was not then?"

This seems to be quite unexpected in a villain like Carker, and while it surely adds some depth to the character, I'm still asking myself whether it would really have been likely for Carker to have given a thought to his despised brother and his sister in that situation. - What do you think?

Then the bitter and brutal end Carker has to face; absolutely breath-taking!

"He heard a shout—another—saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—felt the earth tremble—knew in a moment that the rush was come—uttered a shriek—looked round—saw the red eyes, bleared and dim, in the daylight, close upon him—was beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air.

When the traveller, who had been recognised, recovered from a swoon, he saw them bringing from a distance something covered, that lay heavy and still, upon a board, between four men, and saw that others drove some dogs away that sniffed upon the road, and soaked his blood up, with a train of ashes."

Dickens must really have had it in for Carker in order to have mustered up those dogs to lick up his blood, which is a ghastly and humiliating thing.

Which brings us to an interesting question: Among the villains we got to know so far, where would you place Carker?