Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

I've found time and time again that Dickens based his characters on real people. Could there possibly be a prototype for Miss Havisham Surely not! But ...

I've found time and time again that Dickens based his characters on real people. Could there possibly be a prototype for Miss Havisham Surely not! But ...Eliza Emily Donnithorne of Camperdown, Sydney, a recluse and an eccentric, was believed at the time to be Dickens's model for Miss Havisham, although this has never been proved. Eliza was jilted on her wedding day and spent the rest of her life in a darkened house, leaving her wedding cake to rot as it was on the table, and her front door kept permanently ajar in case her groom ever returned.

Although Charles Dickens saw Australia as a place of opportunity encouraging two of his sons to emigrate there, he never visited it himself. It is central to Great Expectations and he obtained his information from two Sydney researchers, plus numerous friends and acquaintances who had settled in Australia, and sent letters back. He could easily have learned the story from them. Great Expectations was published during the latter years of Eliza's life. The most likely source of his knowledge was through his friendship with Caroline Chisholm, a personal friend of his who was a neighbour of the Donnithornes.

So here is Eliza's true story :)

So here is Eliza's true story :)Eliza Emily Donnithorne was born in 1827, at the Cape of Good Hope, into a wealthy family. Her father, James Donnithorne, descended from an old Cornish family, was a former East India Company Judge, and Master of the Mint. In I836 he retired to the Sydney township of Newtown with his ten year old daughter, Eliza. He purchased "Camperdown Lodge", a Georgian villa named in honour of Lord Nelson's Napoleonic naval victory. Donnithorne was an industrious man, who invested successfully in both property and land in Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales.

Eliza's two teenage sisters and then her mother, Sarah all died of cholera in Calcutta in 1832. Mr Donnithorne attempted to arrange marriages between Eliza, now his only daughter, and the sons of former East India Company colleagues in India. However Eliza was proud and stubbornly refused, saying that she would only marry someone she loved and no one else.

Eliza's refusal to submit to her father meant that they often went for days without speaking. She sought refuge at a church, and here met a young Englishman, George Cuthbertson, who was a shipping company clerk. Since they were from different classes they had to meet in secret, in the grounds of Camperdown Cemetery.

Inevitably her father got to hear of the relationship, and forbade Eliza from seeing her young man. But whenever he went away on business Eliza would send one of the trusted servants with a message to George Cuthbertson, who would then ride out on horseback to Camperdown Lodge, where the couple would spend as much time as possible together.

One day Mr Donnithorne spotted George peering through a window, and and he chased him off in a violent rage. Eliza had to resort to climbing out her bedroom window to meet her beau!

Eventually Mr Donnithorne gave his consent for the couple to court freely, saying that he hoped in this way Eliza would see how unsuitable George was for her. In fact it had the opposite effect. Donnithorne demanded that George resign his job, and live off an allowance with Eliza at Camperdown Lodge after the wedding.

The couple were to marry in 1856. On the morning of the wedding,

"the bride and her maid were already dressed for the ceremony; the wedding-breakfast was laid in the long dining-room, a very fine apartment. On the wedding day, a steady stream of onlookers crowded King Street, Newtown, eager to catch a glimpse of the wedding party in what was very much a high society wedding. The appointed hour of George's arrival came and went; time passed, but still no sign of the groom. The guests dispersed and Eliza remained in an emotional state for several weeks, demanding that the wedding finery be left untouched including the wedding feast on the table.

From that time her habits became eccentric. She never again left the house, finding solace in books and opening the door only to the clergyman, physician and solicitor. The wedding breakfast remained undisturbed on the dining table and gradually moldered away until nothing was left but dust and decay."

Even worse, Eliza was found to be bearing George's child. The child, named Anna, was taken from her and placed with the family of a servant to avoid the inevitable scandal. Eliza was told that the child had died at birth; a particularly difficult pregnancy had kept her bedridden. Eliza eventually recovered but she never left the house again and refused to see anybody.

She insisted that the front door be left permanently ajar so that George would be able to come in, but she kept a mastiff tied up by the door to deter any burglars. George was rumoured to have been located in India some years later. It is possible he was paid off by Eliza's father, but it is not known.

When Mr Donnithorne died, he was survived by two sons, who lived in England. Eliza inherited the bulk of his estate. Now 26 and alone, Eliza became an eccentric recluse.

"The curtains of Camperdown Lodge were drawn and shutters nailed shut. The garden was not tended and became overgrown with weeds. Her brother, Edward, begged her to sell up and take up residence with his family at Colne Lodge near London, but she refused all invitations."

Eliza died on 20th May l886 aged 60 of heart disease, or some say of a broken heart. Camperdown Lodge was put up for sale, and what remained of the wedding feast in the dining room was finally removed, 30 years after it had been laid.

Dickens is certainly not making the young Pip at all appealing to the reader. The older Pip depicts the younger one as a pompous and condescending brat. From chapter 15:

Dickens is certainly not making the young Pip at all appealing to the reader. The older Pip depicts the younger one as a pompous and condescending brat. From chapter 15:"I wanted to make Joe less ignorant and common, that he might be worthier of my society and less open to Estella's reproach."

and chapter 16 or maybe 17, the self-centred young Pip bursts out:

"if I could only get myself to fall in love with you ..." to (view spoiler), with not a thought about how this might make her feel. She is far wiser, responding "but you never will, you see."

Yet earlier, we had this:

"It is a most miserable thing to feel ashamed of home. There may be black ingratitude in the thing, and the punishment may be retributive and well deserved; but that it is a miserable thing, I can testify."

which is clearly the older Pip, the narrator, reflecting on his earlier self and attemping to expiate his guilt. Interesting that we feel the narrator is doing this as a catharsis.

So is this Dickens exaggerating the distance between the callow youthful Pip, and what he is about to become? As well as everything else then, is this to be a "bildungsroman" - a coming of age story?

LOL I like the dramatic irony here. After his visit to Miss Havisham, Pip runs into Mr Wopsle (who else but Dickens could invent a name like that!) who has bought a copy of "The Affecting Tragedy of George Barnwell", which is The London Merchant by George Lillo. This just happens to be a play about a young man (similar to Pip?) who is led astray by a scheming woman (similar to Estella?) with whom he falls in love. Here's the synopsis:

LOL I like the dramatic irony here. After his visit to Miss Havisham, Pip runs into Mr Wopsle (who else but Dickens could invent a name like that!) who has bought a copy of "The Affecting Tragedy of George Barnwell", which is The London Merchant by George Lillo. This just happens to be a play about a young man (similar to Pip?) who is led astray by a scheming woman (similar to Estella?) with whom he falls in love. Here's the synopsis:"Based on an old ballad, it tells the story of an innocent young apprentice, Barnwell, who is seduced by a heartless courtesan, Millwood. She encourages him to rob his employer, Thorowgood, and to murder his uncle, for which crime both are brought to execution, he profoundly penitent and she defiant. It was frequently performed at holidays for apprentices as a moral warning."

Forecasting? Dire warning? A cautionary note, or just a joke?

"Or-lick" = Liquor? Or the Dutch word "oorlog", which means "war"? That seems to fit the brutish nature of the man. "Orc" and "Morlock" have similar sounds to "Orlick", interestingly. A common root, or an early influence?

"Or-lick" = Liquor? Or the Dutch word "oorlog", which means "war"? That seems to fit the brutish nature of the man. "Orc" and "Morlock" have similar sounds to "Orlick", interestingly. A common root, or an early influence?"He pretended that his Christian name was Dolge,—a clear Impossibility,"

Why? It's been suggested that both names are invented by Dickens to be as unpleasant as possible, suggesting the sludge and mud of the marshes, dirtiness and something uncivilised. As the author himself said, "as an affront to decent people".

"destined never to be on the Rampage again" One of Dickens's quips, put in to remind his readers from serial episode to episode. We remember Pip's sister by this characteristic behaviour of hers (which always merits a capital letter!) yet here, because of the events, it has a poignancy.

"destined never to be on the Rampage again" One of Dickens's quips, put in to remind his readers from serial episode to episode. We remember Pip's sister by this characteristic behaviour of hers (which always merits a capital letter!) yet here, because of the events, it has a poignancy.Another one relates to an off-stage comic character:

"Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt conquered a confirmed habit of living into which she had fallen..."

which makes us laugh despite ourselves. She had somehow acquired the bad habit of living, but had been saved from this rut by dying.

Both these comments are so typical of Dickens, using his bitter irony and waspish tone cloaked with humour and wit, but are they like either the young or the older Pip?

Do we have a third voice entering?

Trying to work out how old Pip is in chapter 18, "the fourth year of my apprenticeship" so he must be about 18.

Trying to work out how old Pip is in chapter 18, "the fourth year of my apprenticeship" so he must be about 18.Mr Wopsle is someone I'd totally forgotten until this reread :) Dickens is such a joy to read with new details spotted every time.

Ah, Joe is a much better person than Pip is. I wonder if he always will ... and also whether Dickens was writing out his inner sense of shame with Pip. There are echoes of Steerforth for me too; the character who knew he was a bad egg, but wished he weren't.

Pointing fingers

Pointing fingersThere seem to be so many references to pointing fingers! Dickens really seems to enjoy mentioning fingers, in this novel and others too - like Inspector Bucket's finger - and the pointing finger on the ceiling at Lord and Lady Dedlock's house in Bleak House. I expect it's because they can be literal, and also metaphorical. A "finger of doom" or a "finger of fortune". Fingers on signs, and pointing, represent a way to follow.

I'm also thinking of fingers as instructions and commands. Waggling a finger at a child to tell it off. Poking a finger at at someone - Pip will have had a lot of this from his sister! And insults. I'm put in mind of William Shakespeare "'Do you bite your thumb at me, sir?' 'No but I bite my thumb'" A dire insult from one gentleman to another was putting the fleshy part of one's thumb behind the top teeth, and flicking it out again. It was a little like throwing down the gauntlet for a duel, or slapping one's glove against the other's cheek.

What we know of Mr. Jaggers so far is that he keeps his own counsel, and as he keeps telling Pip, never does anything out of kindness, but only because "I am paid to do it". He seems dispassionate, cynical and world-weary.

Does him biting his finger so often indicate that he is biting his thumb at the world, and all its antics? Or is it just another shorthand pointer by Dickens; helpfully telling us that whenever there is a stranger in the room who is biting his finger, it is likely to be Mr. Jaggers? Or a third idea, since there is a lot of aggression in this novel, is that it is an assertive finger, putting people in their place, and making sure they know that Jaggers is far more knowledgeable than they, and in a position of authority.

I also like the idea of the smell of soap on his hands perhaps indicating that it may be part of his profession to whitewash people, or to make the guilty appear innocent of a crime.

"I never could have believed it without experience, but as Joe and Biddy became more at their cheerful ease again, I became quite gloomy. Dissatisfied with my fortune, of course I could not be; but it is possible that I may have been, without quite knowing it, dissatisfied with myself."

"I never could have believed it without experience, but as Joe and Biddy became more at their cheerful ease again, I became quite gloomy. Dissatisfied with my fortune, of course I could not be; but it is possible that I may have been, without quite knowing it, dissatisfied with myself."This foreshadowing increases our suspense, and makes us wonder what on earth is going to happen. It's interesting that Pip brushes off the idea that his dissatisfaction could be anything to do with with his fortune or expectations, but he seems to be aware that he;s losing something. So is he about to change for the better, or for the worse? I'm not sure who is speaking here, the younger Pip or the more mature narrator reflecting back.

The more I think about this, the more sure I am that we have a third voice. The two views become slightly blurred here, and a third voice, the omniscient narrator pushes his way between them. I don't remember Dickens having such clear instances of multiple personalities in his writing before this novel. It also makes the reader sit up and pay attention in readiness for the next part. This must have been so important originally, when you had to wait a whole month for it!

The young Pip is a snob, no doubt about it. He equates success and being a gentleman with the clothes a person wears, wanting "a fashionable suit of clothes" to look the part of a gentleman in London. But since it is the older Pip who describes him this way, are we to take this as irony? Something must be going to happen in the story to make him mature, and realise the errors of his ways. I think this paragraph,

The young Pip is a snob, no doubt about it. He equates success and being a gentleman with the clothes a person wears, wanting "a fashionable suit of clothes" to look the part of a gentleman in London. But since it is the older Pip who describes him this way, are we to take this as irony? Something must be going to happen in the story to make him mature, and realise the errors of his ways. I think this paragraph, "Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts. I was better after I had cried than before,—more sorry, more aware of my own ingratitude, more gentle. If I had cried before, I should have had Joe with me then."

is a bit of foretelling, coming very shortly before we're told, "This is the end of the first stage of Pip's expectations."

He's already beginning to have a double-think and experiencing the confusion of late adolescence.

I loved "a gallon of condescension"! This technique of using the older Pip and the young Pip adds so many layers - including yet more opportunities for humour and lightly sarcastic observations.

But I'm increasingly finding a poignancy about this work, especially in the scenes at Joe's forge.

This part stood out for me,

This part stood out for me,"I left my fairy godmother, with both her hands on her crutch stick, standing in the midst of the dimly lighted room beside the rotten bride-cake that was hidden in cobwebs."

Dickens can't resist bring the world of fairies and spirits into his books, and here this image seemed to have a weird kind of beauty. Instead of seeing Miss Havisham as a grotesque, the reader now begins to see her as benevolent, as the young Pip does, and the strands of cobwebs as gossamer threads. Yet there is rottenness too.

I was interested in Sarah Pocket,

"Sarah’s countenance wrung out of her watchful face a cruel smile. “Good-bye, Pip!—you will always keep the name of Pip, you know.”

(view spoiler).

What marvellous and macabre use of language! Dickens describes leaving the forge with

"and the world lay spread before me."

It makes me think of another sort of "spread" ... Miss Havisham's wedding cake, and her wish to be placed on the table before the Pocket family when she was dead,

"This ... is where I will be laid when I am dead. They shall come and look at me here."

And these chilling words are also overlaid with a deeper significance, which we are to discover near the end of the book.

Some critics have suggested that with "the world lay spread before me" Dickens may be alluding to Paradise Lost by John Milton, specifically when Adam and Eve are evicted from Eden. So is life with Joe in the home-town Pip's version of Eden? Despite the options ahead of him, Is Dickens hinting that he might have lost Paradise?

Furthermore, at Satis House Pip has visited - and even eaten in - a ruined garden. Now he expects Paradise to await him in London. There's quite a lot of Old Testament subtext here, I think.

Mr Trabb and his boy, specifically the relationship between the boy and our young hero, seems to be a recurring theme. The young Oliver Twist and Noah Claypole springs to mind, also young "Master Copperfull" David Copperfield and Uriah Heep, and I think there are others. It seems more than likely to me that Dickens is drawing these characters and hoping to dispel one of his own bad memories from the blacking factory, here.

Mr Trabb and his boy, specifically the relationship between the boy and our young hero, seems to be a recurring theme. The young Oliver Twist and Noah Claypole springs to mind, also young "Master Copperfull" David Copperfield and Uriah Heep, and I think there are others. It seems more than likely to me that Dickens is drawing these characters and hoping to dispel one of his own bad memories from the blacking factory, here.

Oh lovely - the senses conjuring up vivid memories - certain smells or sometimes tunes etc might trigger both childhood memories and the emotions which were allied to them,

Oh lovely - the senses conjuring up vivid memories - certain smells or sometimes tunes etc might trigger both childhood memories and the emotions which were allied to them,"Biddy, having rubbed the leaf to pieces between her hands,—and the smell of a black-currant bush has ever since recalled to me that evening in the little garden by the side of the lane,—said, 'Have you never considered that he may be proud?'"

It's also reminding us of the distance between the older Pip looking back and his youthful self. I feel as if Biddy and Joe to some extent are the centre of this early part. They are grounding and give us a sense of normality to contrast everybody else with.

OK, so up to now, we assume Pip to be the underprivileged child in this novel, don't we? But how about Estella? Both Pip and Estella are similar, in that they've both been denied a normal upbringing.

OK, so up to now, we assume Pip to be the underprivileged child in this novel, don't we? But how about Estella? Both Pip and Estella are similar, in that they've both been denied a normal upbringing. Pip has had very little which is positive in his life. He never knew his parents, and is constantly reminded of how worthless he is by the verbal abuse (and worse) he receives from his sister. He is desperately seeking to escape, and at the beginning of the story we get all the scenes of forboding and danger, as he roams the gloomy marshes. He seems to have no friends either. Even when he "escapes" to Satis House, he receives yet more verbal abuse from Estella.

Yet somehow, he equates the crumbling rot, decay and perversion there with freedom and respect. In his eyes, a wealthy woman of the gentry class invites him to visit her grand house repeatedly. Even when he returns to say goodbye, he is still permitted to enter, although Pumblechook is not. And people who wouldn't give him the time of day a little earlier, such as Mr Trabb the tailor, are now fawning over him and calling him "Sir". Pip has a sort of protector in Joe, but he's a bit ineffectual, and never directly confronts his wife. And this is interesting in itself. We've learnt that Joe's childhood memories (view spoiler) and he doesn't want to repeat the same mistake, and this stops him from preventing his wife going "on the rampage" with the "the Tickler". Yet to my mind this is just a twisted way of a violent history repeating itself.

Estella's experience is hardly any more privileged. Miss Havisham is raising Estella to wreak revenge on the entire male race, specifically every male who falls in love with her. This surely is what we would nowadays consider to be abuse? Estella is imprisoned therefore with her abuser and occasionally meets others who are hardly any better. There are scenes of Miss Havisham’s sycophantic family fawning over her, plus one in the kitchen where they indulge themselves with vicious gossip (which is very entertaining!) while Estella listens in with contempt. But we see that these are her role models, showing us what Estella sees as normal behaviour. Even the visits from Mr. Jaggers do not provide a healthy or normal role model for her.

We think of Pip and Estella as being worlds apart, but in fact their experiences are as similarly warped. What they have in common will affect the way they look at and interact with the world views. Verbal abuse and violence are all confused with love. Estella had a pink face of pleasure, and said that Pip could kiss her straight after she had seen him win a fight.

PART TWO

PART TWOStarts with chapter 20, and (view spoiler). Whenever I've seen an adaptation of Great Expectations, its never even touched the filth, grime and squalor described here, which impresses itself upon Pip. First of all, he is overcome by the heat and oppression of Mr. Jaggers's stuffy office on a hot summer day, and takes a turn in Smithfield of all places!

An earlier novel, Bleak House I think, described Smithfield Market with all the slaughtering of the animals, suffering in such a sorry state. The press reports from the time talked of routine cruelty, but here Dickens just refers to it as a "shameful place, being all asmear with filth and fat and blood and foam" and he turns from this in relief to find himself in .... Newgate prison! A "minister of justice" describes various scenes there with considerable relish, which Pip find "horrible" and he has begun to have "a sickening idea of London".

It's a far cry from the early pastoral scenes with the cows and peaceful scenes of tranquillity. We had the marshes alongside, which seemed to be tied up with forboding, and now Pip's expectations seem to be inextricably linked with this place full of noise, filth, and squalor. He sees cows again, but in a market where they are being horribly slaughtered. This is their destiny. What is his to be? Wemmick tells Pip one may get "cheated, robbed, or murdered in London".

I had forgotten all this! There certainly is a side of London which Victorian novelists too often gloss over - and many adaptations prettify it too - but not Dickens himself!

I'd forgotten too, the rather unfortunate depiction of a Jewish man. I know Dickens attempted to conciliate people who had been averse to his portrayal of Fagin, by making a positive Jewish character in Our Mutual Friend, but this figure of fun seems far more pathetic to me. Here we have Mr. Jaggers outside his office, with various plaintiffs who had been waiting for him,

I'd forgotten too, the rather unfortunate depiction of a Jewish man. I know Dickens attempted to conciliate people who had been averse to his portrayal of Fagin, by making a positive Jewish character in Our Mutual Friend, but this figure of fun seems far more pathetic to me. Here we have Mr. Jaggers outside his office, with various plaintiffs who had been waiting for him, "... Very well. Then you have done all you have got to do. Say another word—one single word—and Wemmick shall give you your money back.”

This terrible threat caused the two women to fall off immediately. No one remained now but the excitable Jew, who had already raised the skirts of Mr. Jaggers’s coat to his lips several times.

“I don’t know this man!” said Mr. Jaggers, in the same devastating strain: “What does this fellow want?”

“Ma thear Mithter Jaggerth. Hown brother to Habraham Latharuth?”

“Who’s he?” said Mr. Jaggers. “Let go of my coat.”

The suitor, kissing the hem of the garment again before relinquishing it, replied, “Habraham Latharuth, on thuthpithion of plate.”

Far from laughing I was wincing, and found the kissing of the gown disturbing and distressing. What's more, this is a scene which several illustrators have pounced as making a great sketch :(

I do love Herbert Pocket so! To me me he'll always be Alec Guinness's version ...

I do love Herbert Pocket so! To me me he'll always be Alec Guinness's version ...The "pale young gentleman" is like the opposite counterpart to Estella. Estella's apparent purpose is to break Pip's heart, treating him with no respect, and when she had to feed him did it as if he were a dog. Even when offered her cheek to kiss, she may have intended to humiliate him, and increase her hold over him.

Herbert is such a contrast, and the scenes where he is demonstrating how to behave in polite society are a delight! So funny, and it is so good-natured of Herbert. He has immediately said that he and Pip are harmonious, asking Pip if he can call him Handel,

"there is a charming piece of music, by Handel, called the Harmonious Blacksmith."

and that it would be a "pleasure" to help Pip adjust to the ways of a gentleman. Herbert uses the words "dear" and "good" whenever he refers to Pip. He is everything decent which Pip has rarely had an opportunity to see. He is frank and friendly, his way of putting Pip right with his table manners is matter of fact, genial and occasionally jokey, and he readily falls in with Pip's insistence not to pursue the subject of his benefactor any more.

In fact it's really quite surprising that Herbert doesn't bear a grudge against a young man who supplanted him in the favours of a rich relative. He is a true gentleman, even if he is impoverished and has a slightly mad (or at least very eccentric) mother. But he is believable - because he has a fault ... he talks everything up. He is impossibly optimistic, and even Pip can see that his descriptions and dreams are a little unrealistic.

In Herbert, though, Pip has found a true friend and perhaps protector, to replace Joe and Biddy in his new life.

I love this chapter! We so needed this after seeing how Pip's sister, Miss Havisham, Estella, Pumblechook and Wopsle, all demean Pip at every available opportunity. And it is so very clever with the device of using Herbert to fill Pip (and us) in with some backstory, and the lowdown on Miss Havisham.

Herbert's parents are really quite hopeless. His mother, in the distant past, was "the only daughter of a certain quite accidental deceased Knight" ... "highly ornamental, but perfectly helpless and useless" ... "to be brought up from her cradle as one who in the nature of things must marry a title, and who was to be guarded from the acquisition of plebeian domestic knowledge."

Herbert's parents are really quite hopeless. His mother, in the distant past, was "the only daughter of a certain quite accidental deceased Knight" ... "highly ornamental, but perfectly helpless and useless" ... "to be brought up from her cradle as one who in the nature of things must marry a title, and who was to be guarded from the acquisition of plebeian domestic knowledge."She is drawn rather in the same mould as Mrs Nickleby, and Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House - especially with regard to the bashing of the baby's head on the table. I feel they were probably based on Dickens's own mother.

These are two comic characters, and not strictly necessary to the story, but they provide fine entertainment, with the servants giving them the runaround!

I like this neat comment,

"Still, Mrs Pocket was in general the object of a queer sort of respectful pity, because she had not married a title; while Mr Pocket was the object of a queer sort of forgiving reproach, because he had never got one."

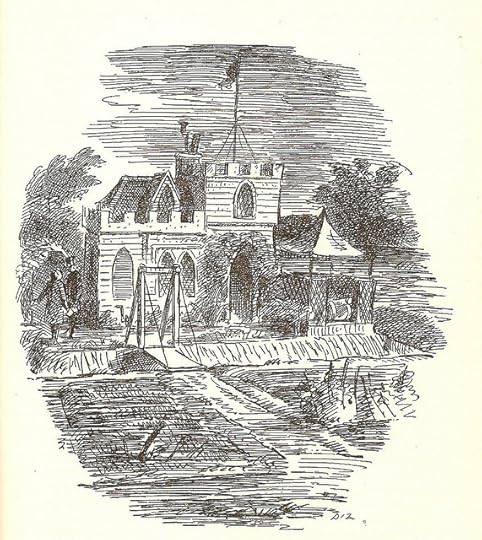

Here is "Restoration House" in Rochester, Kent, which Dickens used as his model for "Satis House":

Here is "Restoration House" in Rochester, Kent, which Dickens used as his model for "Satis House":

And here's their website - link here. You can visit the house.

There's been a lot more about Mr. Jaggers's constant habit of washing his hands. Either he is OCD (which I doubt), or this is a metaphor for him trying to washing his hands of the dirty business he is so often engaged in. Pontius Pilate springs to mind, and also Lady Macbeth. I think the introduction of his maid Molly into the novel is subtle and powerfully done. We immediately begin to conjecture all sorts of things about the (view spoiler).

There's been a lot more about Mr. Jaggers's constant habit of washing his hands. Either he is OCD (which I doubt), or this is a metaphor for him trying to washing his hands of the dirty business he is so often engaged in. Pontius Pilate springs to mind, and also Lady Macbeth. I think the introduction of his maid Molly into the novel is subtle and powerfully done. We immediately begin to conjecture all sorts of things about the (view spoiler).In fact I'm very taken with the contrasting visits Pip has to the two houses, Jaggers's and Wemmick's (chapters 25 and 26). The chapters about Wemmick's home and the "Aged P" make me smile :) I really like this Edward Ardizzone illustration of it:

though I often don't care for the way this illustrator pictures Dickens.

And it occurs to me to marvel at how Dickens can make us find that scene so hugely enjoyable, without feeling that he and we are patronising the Aged P. Another author might not have been able to write this without making us wince a bit.

Dickens does like his symbols and metaphors - and also little motifs and emblems to track through the novel. Pigs keep cropping up and now

Dickens does like his symbols and metaphors - and also little motifs and emblems to track through the novel. Pigs keep cropping up and now Boots!

Pip has started up a boy servant, which the older Pip finds exceedingly embarrassing, as do we:

"I had even started a boy in boots ... top boots ... in bondage and slavery ... I had made this monster out of the refuse of my washer-woman's family"

Perhaps the first time boots had been such a powerful symbol of shame and putting down a person because of his class, was Estella judging Pip on the basis of his boots. Then in chapter 21, as Pip is waiting to meet Matthew Pocket for the first time he:

"... heard footsteps on the stairs. Gradually there arose before me the hat, head, neck-cloth, waistcoat, trousers, boots, of a member of society of about my own standing."

Class through boots again! And in chapter 27, Pip:

"heard Joe, on the staircase. I knew it was Joe by his clumsy manner of coming up-stairs ... his state boots being always too big for him."

It also seems as though stairs are important here as a metaphor for Pip's rise in society.

Then in chapter 27 and 28 we have convicts again - and shackled, just as Pip is shackled in his new life. Joe's high collar is constraining and imprisoning him. We have the same dreary, gloomy weather during the coach ride which conjures up the early marsh scenes. Pip has taken on "the Avenger" Pepper, the boy with the boots, and set him up as a servant he can lord it over, and who is compared with Trabb's boy, who used to snub and laugh at him. To cap it all Miss Havisham is set to reappear! These two chapters seem to deliberately throw this new, unlikable Pip, back into the scenes of his origins.

I find Joe's visit so hard to read. Yes, the parts with the hat are as funny a scene as Dickens ever writes, but ... the unbearable pathos tops it somehow. I don't completely condemnatory about Pip though, as I feel the narrator is feeling mortified by his earlier priggish self.

I find Joe's visit so hard to read. Yes, the parts with the hat are as funny a scene as Dickens ever writes, but ... the unbearable pathos tops it somehow. I don't completely condemnatory about Pip though, as I feel the narrator is feeling mortified by his earlier priggish self. I am enjoying the switching and blending of the different voices very much, and beginning to hear a "third voice" in there which is neither the young nor the older Pip.

Pigs, manacles etc

There are so many references to pigs in this novel! When he was very young and living in the forge, Pip was compare with a pig at the table (by Pumblechook I think, from memory). Now, when Pip eats with Joe, Joe mentions the inn where he's staying, saying:

"I wouldn't keep a pig in it myself ... not in the case that I wished him to fatten wholesome and to eat with a meller flavour on him". which seems quite dramatic!

I'm not sure of the meaning of "their ironed legs, apologetically garnered with pocket handkerchiefs" in respect of the two convicts. The only other time I can remember pocket handkerchiefs is when Fagin was teaching his boy pickpockets how to steal them.

Perhaps the handkerchiefs could be to conceal the offensive (to Victorian eyes) sight of chains?

There is a constant hammering home of being trapped and shackled in this book though, and the leg-irons are a manifestation of that. We've already had Pip seeing prisoners dangle "their ironed legs over the coach roof ... more than once". Then he comments about the two convicts at the coach station with "irons on their legs - iron of a pattern that I knew well." throwing us mentally back to his earlier experience with a convict. Now these "ironed legs" with the handkerchiefs. Dickens said that these two were coarse and mangy, "as if they were lower animals". And once more this part of the body is very close to the feet, in a similar way to the boots. Right at the beginning Pip's own convict desperately wanted a file, so that he could remove his leg irons, and gain his freedom.

Then there are the handkerchiefs though. Is it a play on words perhaps? "Ironed legs" can mean being shackled by iron manacles, but also "ironed" in the sense of being smoothed out - as implied by the handkerchiefs. What is the function of those handkerchiefs? To stop the chafing of the leg-irons? I can't somehow see them being issued with them by the officials bothering about whether convicts had something about them to blow their noses with. It seems far too genteel!

"their ironed legs, apologetically garnered ... " The word "garnered" is such a descriptive word. Anyone casually looking would see not leg-irons but that the prisoners' legs were rather colourfully decorated with cloth. Or is it another pig reference? You "garnish" pork, and perhaps the convicts' legs were "decorated" with handkerchiefs in this way as a consequence of fabric being stuffed in there to stop the irons chafing - but why "apologetically"?

Oh yet more about footwear in chapter 29! As well as Pip twice mentioning the fact that he ascended the staircase to meet Miss Havisham "in lighter boots than of yore" to the "yellow-green" (LOL!) Sarah Pocket - that his boots were not as thick as they used to be, when he first sets his eyes on (view spoiler) she is holding in her hand the white unworn slipper of Miss Havisham - and casts it aside. Talk about redolent of symbolism! Is Estella meant to step into her shoes, Or is there more than that, even?

Oh yet more about footwear in chapter 29! As well as Pip twice mentioning the fact that he ascended the staircase to meet Miss Havisham "in lighter boots than of yore" to the "yellow-green" (LOL!) Sarah Pocket - that his boots were not as thick as they used to be, when he first sets his eyes on (view spoiler) she is holding in her hand the white unworn slipper of Miss Havisham - and casts it aside. Talk about redolent of symbolism! Is Estella meant to step into her shoes, Or is there more than that, even?This is an odd little tableau. It reminds me of Cinderella, but it's rather like a fractured fairy tale, with a reversal of roles. Interestingly both the story of Cinderella and Great Expectations have time as a major focus. Clocks, timepieces and the passage of time, are all major motifs in Dickens's novels. In this one, Miss Havisham's world stopped/changed at 8:40, and for Cinderella, of course, her world changed at midnight.

I think most readers will thoroughly dislike the young gentleman Pip is proving to be, (view spoiler) I'm afraid I do find this squares with human nature, sometimes, but since the older Pip is writing quite candidly of it, we may live in hope that he sees the error of his callow earlier ways!

I think most readers will thoroughly dislike the young gentleman Pip is proving to be, (view spoiler) I'm afraid I do find this squares with human nature, sometimes, but since the older Pip is writing quite candidly of it, we may live in hope that he sees the error of his callow earlier ways!I don't understand the significance of (view spoiler). Either I'm missing something here, or have forgotten some future event, or it's one of those "undeveloped plot-lines just in case" which Dickens used to strew around the place, though I'd thought they featured more in his earlier, less rigorously planned and tightly plotted novels.

Im not sure of the significance of where Orlick is now - (view spoiler)

Im not sure of the significance of where Orlick is now - (view spoiler) And this from Jaggers is particularly inscrutable:

"of course he is not the right sort of man ... because the man who fills the post of trust never is the right sort of man."

ch 30 and 31 - Both written more for comedy than to move the story along, I think. An hilarious description of Mr Wopsle's theatrical "talent", which I feel must be drawn from life, given Dickens's love of the theatre. Ir was preceded by more instances of Pip's peevishnesses, reporting (view spoiler) to Mr Jaggers so that he would be dismissed - then affecting not to want this to be the case. Then repeating the self-same thing with Trabb's boy.

ch 30 and 31 - Both written more for comedy than to move the story along, I think. An hilarious description of Mr Wopsle's theatrical "talent", which I feel must be drawn from life, given Dickens's love of the theatre. Ir was preceded by more instances of Pip's peevishnesses, reporting (view spoiler) to Mr Jaggers so that he would be dismissed - then affecting not to want this to be the case. Then repeating the self-same thing with Trabb's boy. Pip seem to be so stuffy and po-faced that he does not realise how these three stages of Trabb's boy's mimicry reflect Pip's own development into a so-called gentleman. It is as much a parody as anything he is likely to see on the stage!

And yet Pip can only ever be playing a part, much as Mr Wopsle was playing a part. Very funny scenes nevertheless.

Thinking of the different voices, and the fact that the young Pip is described by a rather more mature and likeable Pip, I like some of G.K. Chesterton's thoughts:

Thinking of the different voices, and the fact that the young Pip is described by a rather more mature and likeable Pip, I like some of G.K. Chesterton's thoughts:"Great Expectations, which was written in the afternoon of Dickens's life and fame, has a quality of serene irony and even sadness, which puts it quite alone among his other works ... The best way of stating the change which this book marks in Dickens can be put in one phrase. In this book for the first time the hero disappears ...

Great Expectations may be called, like Vanity Fair, a novel without a hero ... I mean that it is a novel which aims chiefly at showing that the hero is unheroic ... in Great Expectations Dickens was really trying to be a quiet, a detached, and even a cynical observer of human life. Dickens was trying to be Thackeray ...

Take, for example, the one question of snobbishness. Dickens has achieved admirably the description of the doubts and vanities of the wretched Pip as he walks down the street in his new gentlemanly clothes, the clothes of which he is so proud and so ashamed. Nothing could be so exquisitely human, nothing especially could be so exquisitely masculine as that combination of self-love and self-assertion and even insolence with a naked and helpless sensibility to the slightest breath of ridicule. Pip thinks himself better than every one else, and yet anybody can snub him; that is the everlasting male, and perhaps the everlasting gentleman. Dickens has described perfectly this quivering and defenseless dignity. Dickens has described perfectly how ill-armed it is against the coarse humour of real humanity—the real humanity which Dickens loved, but which idealists and philanthropists do not love, the humanity of cabmen and costermongers and men singing in a third-class carriage; the humanity of Trabb's boy..."

I had forgotten Herbert Pocket's parents! One of Dickens's dottiest females on the lines of Mrs Nickleby and various others. But the irony of Mr Pocket senior lecturing on practical household matters is wonderfully funny:

I had forgotten Herbert Pocket's parents! One of Dickens's dottiest females on the lines of Mrs Nickleby and various others. But the irony of Mr Pocket senior lecturing on practical household matters is wonderfully funny:""Mr. Pocket was out lecturing; for, he was a most delightful lecturer on domestic economy, and his treatises on the management of children and servants were considered the very best text-books on those themes. But Mrs. Pocket was at home, and was in a little difficulty, on account of the baby’s having been accommodated with a needle-case to keep him quiet during the unaccountable absence (with a relative in the Foot Guards) of Millers. And more needles were missing than it could be regarded as quite wholesome for a patient of such tender years either to apply externally or to take as a tonic."

Oh I think everyone reading this novel must want to take the young man Pip has become by the throat and shake some sense into him. Ostentatiousness and self-deception seem to be his byword, if the older Pip is presenting a true likeness (and why would he not?)

Oh I think everyone reading this novel must want to take the young man Pip has become by the throat and shake some sense into him. Ostentatiousness and self-deception seem to be his byword, if the older Pip is presenting a true likeness (and why would he not?)I'm thinking now of his protestations that he would always be at the Forge with Joe (view spoiler)Clear-sighted Biddy can see that this is most unlikely - yet meekly gives in to his chastisement.

“No, don’t be hurt,” she pleaded quite pathetically; “let only me be hurt, if I have been ungenerous.”

Once more, the mists were rising as I walked away. If they disclosed to me, as I suspect they did, that I should not come back, and that Biddy was quite right, all I can say is,—they were quite right too."

Is it self-deception - or worse is it all show? Probably not. The older Pip also reflects:

"I should have been happier and better if I had never seen Miss Havisham's face, and had risen to manhood content to be partners with Joe in the honest old forge. Many a time of an evening, when I sat alone looking at the fire, I thought, after all, there was no fire like the old forge fire and the kitchen fire at home." And he uses the word "home" and "forge" as synonymous.

Two of Dickens's own preoccupations here;

Two of Dickens's own preoccupations here;1. the hatred of showy funerals (he even had a clause in his will that there should be none such for him) and

2. people who could not manage their money properly (like his own father).

Pip does business by "leaving a Margin" - which we can see would lead to more borrowing and ultimate ruin. It reminds me also of Mr. Micawber's financial theory for achieving happiness and avoiding ruin:

"Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery."

Here is Joe Gargery's Forge and blacksmiths cottage at Chalk near Rochester, Kent. It's now a listed building:

Here is Joe Gargery's Forge and blacksmiths cottage at Chalk near Rochester, Kent. It's now a listed building:

Ch 36 - Interesting that when Pip is to consult Mr Jaggers, on his coming of age, he feels:

Ch 36 - Interesting that when Pip is to consult Mr Jaggers, on his coming of age, he feels:“at a disadvantage, which reminded [him] of that old time when [he] had been put upon a tombstone.”

I like this (view spoiler), although it can't be recognised as this on a first reading.

ch 37 - at last we have some indication that Pip is not going to continue to be a spoiled arrogant brat! He wants to (view spoiler)while Pip himself is waiting in frustration to find out who his benefactor is. His innermost thoughts seem to shop that he is more and more convinced that he already knows.

ch 37 - at last we have some indication that Pip is not going to continue to be a spoiled arrogant brat! He wants to (view spoiler)while Pip himself is waiting in frustration to find out who his benefactor is. His innermost thoughts seem to shop that he is more and more convinced that he already knows.I'm not sure how to square this generosity with the Pip we have seen so far though - it seems quixotic - foolish and irresponsible (which is in character ...) but also to have come out of the blue. It's not at all in the same league as sending the oysters to the Blue Boar - that was just guilt.

I love all these descriptions of Pip's various visits to Wemmick's home in Walworth. And the description of Wemmick's outrageous flirting with Miss Skiffins, his lady friend, was hilarious!

It's pretty clear in the narrator's voice, how embarrassed he is by his earlier self. (view spoiler) - there are a wealth of details if you look - but it's also in the attitude and thought process of the youth described by the narrator.

It's pretty clear in the narrator's voice, how embarrassed he is by his earlier self. (view spoiler) - there are a wealth of details if you look - but it's also in the attitude and thought process of the youth described by the narrator.Is this Dickens himself, a little ashamed of his own behaviour perhaps?

The developing character of Pip

The developing character of PipG.K. Chesterton hit the nail on the head (post 494) I think. What's intriguing me about this is the different and melding voices of Pip, through to the fully adult one who is ostensibly narrating.

The young boy was beset with guilt, mostly due his sister, armed with "the Tickler". He was an interesting child, as even then, despite feeling guilty about everything, he had a strong sense of resentment that he didn't want to labour like Joe - and felt guilty about that too! That guilt magically disappeared when he got what he wanted. His template for the life of wealth he so desired was Satis House - such a very odd one - plus of course his burgeoning hormones with Estella.

Then we have the young, arrogant, insufferable Mr Pip. Because he can decide more for himself what to do and where to go, we see more of his essential character through his actions, though the older Pip also hammers it home with his confessional style of regret.

We also then have this future unknown Pip, one who seems to be supremely moral and wants to tell his story, warts and all, as a sort of cathartic action. And this is all filtered through Dickens who, at the best of times, finds it hard to keep his own views out of it all, and can't resist his quirky cameos and discursive episodes (nor would we want him to!)

They merge and change, as time moves on, but we get echoes. I think the "commentary" on this usually comes at the end of chapters, or the end of a particular event, as the older Pip muses on his younger self.

(view spoiler).

Unfortunately I do find him totally believable ... just not likable. I think dramatisations are usually very kind to Pip, and because they have to simplify the book so much, they present him as a young lad struggling with his changes of circumstances - another of Dickens's Bildungsroman. But all his protagonists are very different, so although the principle/structure of this boy's journey is "pretty familiar stuff", I don't think the treatment is. It must have been quite difficult for Dickens to curb his instinct to make us like his protagonist! He might have lost sales if his readers couldn't identify with him. I wonder if that why he chose to have a more sympathetic adult narrator.

ch 38 is all about Estella, and Pip is mooning about his "star" as much as ever, even though she warns him not to care so much. I found this interesting, as it shows Estella has some feeling for him, if only an awareness that he is some way "different" from her other suitors.

ch 38 is all about Estella, and Pip is mooning about his "star" as much as ever, even though she warns him not to care so much. I found this interesting, as it shows Estella has some feeling for him, if only an awareness that he is some way "different" from her other suitors.I find this chapter very upsetting with the almost grovelling Miss Havisham. If she was not a broken woman before, she seems to have reached a new low level of degradation now, contrasting with Estella.

“So proud, so proud!” moaned Miss Havisham, pushing away her gray hair with both her hands.

“Who taught me to be proud?” returned Estella. “Who praised me when I learnt my lesson?”

This is almost a repetition of a relationship from an earlier novel Dombey and Son. In that one, Mrs Skewton, a grotesque old crone, seemed to be almost a practice run for Miss Havisham, and her daughter, the widowed Edith Granger, was at that point in the novel a haughty individual - very much a nascent Estella:

"‘What do you mean?’ returned the angry mother. ‘Haven’t you from a child—’

‘A child!’ said Edith, looking at her, ‘when was I a child? What childhood did you ever leave to me? I was a woman—artful, designing, mercenary, laying snares for men—before I knew myself, or you, or even understood the base and wretched aim of every new display I learnt’"

Other quotations I liked:

Other quotations I liked:“What!” said Miss Havisham, flashing her eyes upon her, “are you tired of me?”

“Only a little tired of myself,” replied Estella, disengaging her arm, and moving to the great chimney-piece, where she stood looking down at the fire."

...

"Moths, and all sorts of ugly creatures," replied Estella, with a glance towards him, "hover about a lighted candle. Can the candle help it?"

...

"She hung upon Estella's beauty, hung upon her words, hung upon her gestures, and sat mumbling her own trembling fingers while she looked at her, as though she were devouring the beautiful creature she had reared"

Such a sad chapter, and I feel Pip's obsession almost fades into the background. Dickens is writing particularly strong women in this novel.

ch 39 reaches "The end of Pip's Second Stage of Expectations" and moves the plot along considerably, introducing a new, or not so new, character (view spoiler). Pip still comes across as a patronising prig:

ch 39 reaches "The end of Pip's Second Stage of Expectations" and moves the plot along considerably, introducing a new, or not so new, character (view spoiler). Pip still comes across as a patronising prig:"If you are grateful to me for what I did when I was a little child, I hope you have shown your gratitude by mending your way of life. If you have come here to thank me, it was not necessary."

who can buy his way out of any sticky situation, even though it is not by any hard-earned money of his own. But there is one shaft of hope that he may be developing a conscience:

(view spoiler)

ch 40 - some humour after the devastating events of the previous chapter:

ch 40 - some humour after the devastating events of the previous chapter: "I was looked after by an inflammatory old female, assisted by an animated rag-bag whom she called her niece ... They both had weak eyes, which I had long attributed to their chronically looking in at keyholes, and they were always at hand when not wanted; indeed that was their only reliable quality besides larceny.”

"As to forming any plan for the future, I could as soon have formed an elephant.”

The idea of creating people is taken even further by Dickens:

"The imaginary student pursued by the misshapen creature he had impiously made, was not more wretched than I, pursued by the creature who had made me, and recoiling from him with a stronger repulsion, the more he admired me and the fonder he was of me.”

seems to be a specific reference to Frankenstein

Pip seems to have taken on board all the undesirable aspects of being a gentleman, rather than the honourable ones. (view spoiler)

Pip seems to only care for the position and status of being a gentleman. (view spoiler) It is the supreme irony and Pip has yet a long way to go in his expectations. I hadn't remembered that Dickens painted him as such an obnoxious little prig for the first two thirds of the book, with only a little hint right at the end of chapter 40.

Pip seems to only care for the position and status of being a gentleman. (view spoiler) It is the supreme irony and Pip has yet a long way to go in his expectations. I hadn't remembered that Dickens painted him as such an obnoxious little prig for the first two thirds of the book, with only a little hint right at the end of chapter 40.

"Moral Regeneration": (good article about Great Expectations on Wiki)

"Moral Regeneration": (good article about Great Expectations on Wiki)"Pip represents, as do those he mimics, the bankruptcy of the "idea of the gentleman", and becomes the sole beneficiary of vulgarity, inversely proportional to his mounting gentility. In chapter 30, Dickens parodies the new disease that is corroding Pip's moral values through the character "Trabb's boy", who is the only one not to be fooled. The boy parades through the main street of the village with boyish antics and contortions meant to satirically imitate Pip. The gross, comic caricature openly exposes the hypocrisy of this new gentleman in a frock coat and top hat. Trabb's boy reveals that appearance has taken precedence over being, protocol on feelings, decorum on authenticity; labels reign to the point of absurdity, and human solidarity is no longer the order of the day."

The one for "Pip (Great Expectations)" - is not so good - and even has grammatical errors :(

Lots of traps and bindings in this book. At the end of chapter 9 Dickens said,

Lots of traps and bindings in this book. At the end of chapter 9 Dickens said,"Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, and that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day." using the voice of the mature Pip.

This metaphor struck me, as it kept cropping up in A Tale of Two Cities, to indicate prisons and traps. I think there it was usually a "thread of gold" referring in a double meaning to Lucie Manette's hair.

By now in chapters 41-42, we have learned that there are ties between (view spoiler) - they are all bound together in some way, and interconnected, although we are not sure yet of the full extent.

Pip and Magwitch were linked from the very start by iron and chains. Now that Pip's expectations have been revealed, we understand that iron and chains are still at the crux. Similar golden hopes for Estella are revealed to be base iron. (view spoiler)

This then has to be the turning point, the"memorable day" and hopefully will necessitate a sea change in Pip, making him review his life so far and develop some moral fibre at last. We will come to see, as David Copperfield did, whether he "comes to be the hero of his own life".

Chapters 43-44 were both very affecting. The part where Pip and Bentley Drummle jostling each other in front of the fire strikes me as some of Dickens funniest writing, comparable with the marriage proposal by vegetable (cucumber?) over the garden fence in Nicholas Nickleby :D I am actually finding far more humour in this novel than I ever remember before, which is amazing considering its seriously weird characters and tragic events.

Chapters 43-44 were both very affecting. The part where Pip and Bentley Drummle jostling each other in front of the fire strikes me as some of Dickens funniest writing, comparable with the marriage proposal by vegetable (cucumber?) over the garden fence in Nicholas Nickleby :D I am actually finding far more humour in this novel than I ever remember before, which is amazing considering its seriously weird characters and tragic events. Dickens's description of Pip's servant in chapter 40, which I already mentioned:

"an inflammatory old female, assisted by an animated rag-bag whom she called her niece, and to keep a room secret from them would be to invite curiosity and exaggeration. They both had weak eyes, which I had long attributed to their chronically looking in at keyholes, and they were always at hand when not wanted; indeed that was their only reliable quality besides larceny.”

also made me have tears of laughter rolling down my cheeks.

But how sorry I felt for poor Miss Havisham. It's as if her single-minded vengeance took her by surprise. She genuinely had not expected Estella to be cold towards her. Interesting. Does this imply that she herself is consciously acting the part of the "batty old woman"?

Ah knitting! Yes, threads to bind and entrap, but also another echo of A Tale of Two Cities; this time Madame Defarge.

I now view Miss Havisham as a broken reed; a tragic character and it just piles on, later :(

I now view Miss Havisham as a broken reed; a tragic character and it just piles on, later :(Chapter 45 is quintessential Dickens, isn't it? All those night horrors, where events of the day assume gigantic proportions. And who else but Dickens could make pieces of furniture so very funny? I'm thinking of the description of the Hummums in Covent Garden, where:

"a bed was always to be got...at any hour of the night...It was a sort of a vault on the ground floor at the back, with a despotic monster of a fourpost bedstead in it, straddling over the whole place, putting one of his arbitrary legs into the fireplace, and another into the doorway, and squeezing the wretched little washing-stand in quite a Divinely Righteous manner.""

I love this! And I'm sure I've lived in bedsits like that in the past ... though maybe not with a four poster bed ;)

I wonder if Dickens had a horror of crawly things. Great Expectations seems to be chock-a-block with them - remember all those in Satis House? And I seem to remember in previous novels, all the sick beds, or whenever anyone gave birth, the ceilings were black with flies, and collected in jam jars. Ditto the prisons, (though perhaps that's not so surprising).

And Chapter 46 also could only have been written by Dickens! We see so many adaptations of this particular novel, that I forget all the details which they invariably miss out. Herbert's ladylove Clara's family is a scream; her growling father "Old Barley" or as Herbert terms him "Old Gruffandgrim". I do like Herbert! He seems so determined to see the best in everyone :)

And Chapter 46 also could only have been written by Dickens! We see so many adaptations of this particular novel, that I forget all the details which they invariably miss out. Herbert's ladylove Clara's family is a scream; her growling father "Old Barley" or as Herbert terms him "Old Gruffandgrim". I do like Herbert! He seems so determined to see the best in everyone :)I also like that Dickens incorporates fairytales into the most unlikely scenarios, and has Pip imagining Clara as a captive fairy, and Old Barley as an ogre, who has imprisoned her and kept her captive, to look after him.

Most of all I am struck with the contrast between the two old curmudgeons. There's Wemmick's dear old nodding father, and this one, behaving like an ogre. It seems to be a common theme in Dickens to have an elderly relative with an overbearing manner, and a powerless and innocent youngster under their control.

There are also signs in this chapter that Pip may be developing a smidgen of humanity - at least he seems to be bonding or beginning to care about (view spoiler)

Also, Pip is at last beginning to learn what a home is, and what value to place on it. There are many in this novel who either have no home, or an unsatisfactory home.

Also, Pip is at last beginning to learn what a home is, and what value to place on it. There are many in this novel who either have no home, or an unsatisfactory home.Home is uppermost in our minds.

"Don't go home!" is the starting point for all those nightmares of Pip's, the spookily absurd descriptions of which delighted us so much.

I'm also struck by the number of name-changes we have here. Just as in David Copperfield, David was "Davy, David, Daisy, Doady, Master Copperfull" etc, according to whose viewpoint of him we had, here (view spoiler)

Chapter 47, in which Dickens indulges his love of all things theatrical I found a little tiresome. I don't think I find Mr Wopsle as entertaining as Dickens intended me to. But it was important to further the plot, in what Mr Wopsle tells Pip, and we and Pip can deduce, about his "shadow", "like a ghost" - so Dickens!!

Chapter 47, in which Dickens indulges his love of all things theatrical I found a little tiresome. I don't think I find Mr Wopsle as entertaining as Dickens intended me to. But it was important to further the plot, in what Mr Wopsle tells Pip, and we and Pip can deduce, about his "shadow", "like a ghost" - so Dickens!!Chapter 48 too, at Mr Jaggers's house, is great for furthering the plot. Lots of intrigue here! And it's confirmed with Wemmick later.

It was thrilling to see how Pip works out (view spoiler) And knitting! Webs of deceit, much like the knitting Madame Defarge. Lovely powerful writing :)

Oh chapter 49 is so very sad, with such a broken, pitiful figure we see before us:

Oh chapter 49 is so very sad, with such a broken, pitiful figure we see before us:"[t]here was an air of utter loneliness upon her, that would have moved me to pity though she had wilfully done me a deeper injury than I could charge her with.”

“O!” she cried, despairingly. “What have I done! What have I done!”

"What have I done?" Such simple, powerful words. I want to weep at this chapter, with its character so full of remorse, sorrow and grief.

Yet for all its directness, it is clever and subtle, moving the story forward in an important way. It shows that Pip is gaining in moral stature, feeling true compassion for someone whom a younger Pip may well have resented for allowing him to proceed under a misapprehension, and also for continuing to want to help his friend in any way he can, even though it means a rather humbling action.

Oh! And the thrilling, heart-stopping, horrifying end to the chapter! I remember when I was very young, watching a black and white TV dramatisation of this, on Sunday teatime. It gave me nightmares, and I woke up screaming night after night! My parents remembered it for years afterwards!

Oh! And the thrilling, heart-stopping, horrifying end to the chapter! I remember when I was very young, watching a black and white TV dramatisation of this, on Sunday teatime. It gave me nightmares, and I woke up screaming night after night! My parents remembered it for years afterwards!(view spoiler)

Wow! Now I still find it hair raising - and had forgotten that Pip had a sort of premonition, and an hallucination just before it. There's always an inexplicable ghostly or other-worldly dimension with Dickens, even to (view spoiler)

And of course we mustn't forget all the scurrying and scuttling crawly things again!

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

All these characters seem to have been female! I wonder if there has been a period of history when women, feeling trapped by their circumstances, developed this sort of behaviour or overlaid personality. Men's refuges would perhaps be the pub, which any decent woman would not step inside. Often their incarceration would be domestic, and perhaps they would not resort to solitary drinking with children to consider, hence the martyrdom.

Miss Havisham is an exception to this rule of course, but she has elected for self-incarceration, which has the same end result.