Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

Chapter 55 I found incredibly powerful and kept having to stop to breathe! (view spoiler) went on so long - over several pages. Yet I felt it was totally gripping. The drama of the description really took hold of me, it was so overwhelming. I cannot remember feeling such intensity and vividness in his writing since the horrific descriptions of the riots in Barnaby Rudge.

Chapter 55 I found incredibly powerful and kept having to stop to breathe! (view spoiler) went on so long - over several pages. Yet I felt it was totally gripping. The drama of the description really took hold of me, it was so overwhelming. I cannot remember feeling such intensity and vividness in his writing since the horrific descriptions of the riots in Barnaby Rudge.

My next read is therefore Bleak House, which I'm really excited about since it was my favourite through last time. I've met a bit of a blip but will be starting tomorrow.

My next read is therefore Bleak House, which I'm really excited about since it was my favourite through last time. I've met a bit of a blip but will be starting tomorrow.I started reading a Large Print copy but it was 11" x 8" and a half (28 x 21cm) and an inch and three quarters thick. It weighed a ton. Not only that but there were virtually no margins or indents in the paragraphs - it was just like reading a big block of text. I love having a print version of a classic, but why they didn't print it in two volumes I don't know! I've just read "David Copperfield" that way.

Anyway I've passed it on to a charity shop now, and hope that some muscle-bound reader can cope. (The trouble is, visually impaired people are quite often old and frail!) I'll be reading it on kindle, as I have with most of his novels so far in this challenge.

BLEAK HOUSE

:

BLEAK HOUSE

: Here is the original schedule, over 20 monthly instalments. You can see that the first readers had to read it spread over a year and a half, whether they liked it or not! This always makes me think, when I wonder how long to reserve for any one book (a day ... a week ... a month ... a year and a half ?!)

Issue number - Date - Equivalent Chapter numbers:

I - March 1852 1–4

II - April 1852 5–7

III - May 1852 8–10

IV - June 1852 11–13

V - July 1852 14–16

VI - August 1852 17–19

VII - September 1852 20–22

VIII - October 1852 23–25

IX - November 1852 26–29

X - December 1852 30–32

XI - January 1853 33–35

XII - February 1853 36–38

XIII - March 1853 39–42

XIV - April 1853 43–46

XV - May 1853 47–49

XVI - June 1853 50–53

XVII - July 1853 54–56

XVIII - August 1853 57–59

XIX–XX - September 1853 60–67

Bleak House was Charles Dickens's ninth novel, written when he was between 40 and 41 year of age. It was illustrated by his favourite illustrator and great friend Hablot Knight Browne, "Phiz".

Bleak House was Charles Dickens's ninth novel, written when he was between 40 and 41 year of age. It was illustrated by his favourite illustrator and great friend Hablot Knight Browne, "Phiz".This novel is often considered Dickens' finest work although it is not by any means his most popular. Dickens intended it to illustrate the evils caused by long, drawn-out suits in the Courts of Chancery. Much of it was based on fact, as Dickens had observed the inner workings of the courts as a reporter in his youth. In Bleak House he observes bitterly:

"The one great principle of the English law is to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it. Let them but once clearly perceive that its grand principle is to make business for itself at their expense, and surely they will cease to grumble."

This, then, is the crux of the story, but it is wrapped in a magnificently complex tale of mystery :)

As always, Dickens's life during the writing and initial serialisation of his next novel was eventful!

As always, Dickens's life during the writing and initial serialisation of his next novel was eventful!In March 1852, his son Edward Bulwer Lytton (Plorn) Dickens was born. During the Summer of that year, Dickens's amateur acting troupe were on tour throughout England.

In February 1853, he became involved in a public controversy about spontaneous combustion, which is directly relevant to an episode in the novel. In the introduction to the novel form of Bleak House later, the author still refers to this argument. George Henry Lewes had argued that the phenomenon was a scientific impossibility, but Dickens maintained that it could happen.

In June 1853, Dickens became seriously ill with a recurrence of a childhood kidney complaint. He was bedridden for six days, but still had 17 chapters to write. He then went to Boulogne, France to recover. In August of that year, he celebrated finishing Bleak House by holding a banquet in Boulogne. His publishers Bradbury and Evans, were there, and also his close friend, the writer Wilkie Collins.

What an amazingly accurate description of London's gloom in November, at the start of Bleak House:

What an amazingly accurate description of London's gloom in November, at the start of Bleak House:"Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another's umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest."

l'm tempted to say it's still like that even now, all the rain, mud, fog, smog, dirt and dreariness - but that's a bit of an exaggeration ;)

However these first three or four chapters are real attention- grabbers. Straightaway we're introduced to the pivotal point of the book, the High Court of Chancery and the name Jarndyce, and the fact that this comes into the narration time and time again shows us how important it's going to be. Charles Dickens has already told us in the Preface that it's going to be about artificially drawn out lawsuits.

The first three chapters are set in three entirely different locations, with different sets of characters and events. The only connection between them seems to be this "Jarndyce and Jarndyce", though we still have no idea what it's all about.

We learn of the traditional Lord Leicester Dedlock and the fashionably bored and languid "My Lady" Dedlock - lovely descriptions of these two.

Then suddenly in chapter 3 we switch from an objective narrator to to a first party narrator - a young girl called Esther. I remember he did this once before, in The Old Curiosity Shop, but there it was because he wanted to switch the mood. I'm not sure why he's doing it now.

Then suddenly in chapter 3 we switch from an objective narrator to to a first party narrator - a young girl called Esther. I remember he did this once before, in The Old Curiosity Shop, but there it was because he wanted to switch the mood. I'm not sure why he's doing it now. But I do know that Esther's story was incredibly moving. The idea of making a child feel guilty for having been born! That her birthday "was the most melancholy ... in the whole year." Oh :( And the woman (view spoiler) who looked after her, who from a child's point of view must have been so "good" because she went to church so much and frowned at everybody else's sin. A child can't see an adult's sanctimonious, holier-than-thou behaviour, and only thinks it must be good.

It's interesting. I don't think Dickens ever has a female narrator except for this one novel.

At this point I realised that the description of the "London Particulars" (fog) is actually a metaphor for the events which are to follow in the story.

At this point I realised that the description of the "London Particulars" (fog) is actually a metaphor for the events which are to follow in the story. The "fog" of the legal system ("Mlud", is only one letter different from "mud") and the foggy unknown future of the three young people we are about to meet: Esther, and Richard and Ada, the wards of Jarndyce. There is a sort of "fog" about the entire story - all the myriad strands.

And already we have lots of mysteries ... (view spoiler)

What fabulous minor characters! I was chuckling quite a lot at these! Especially:

What fabulous minor characters! I was chuckling quite a lot at these! Especially:Mrs. Jellyby

Apparently she was based on a real person - Caroline Chisholm, who had started out as an evangelical philanthropist in Sydney, Australia, then moved to England in 1846. Over the next six years Caroline assisted 11,000 people to settle in Australia.

Dickens apparently admired her greatly, and supported her schemes to assist the poor who wished to emigrate. But he was appalled by how unkempt her own children were and the general neglect he saw in her household. Of course he couldn't resist painting her portrait as Mrs. Jellyby ...

I've just realised how relieved I am to discover Mrs. Jellyby was based on a real person. Otherwise it just seems poking fun regardless, to hammer home his view that women should primarily focus on their household and their children instead of engaging in any social activities. Apparently John Stuart Mill hated the character, thinking it was an attack by Dickens on women's rights.

I've just realised how relieved I am to discover Mrs. Jellyby was based on a real person. Otherwise it just seems poking fun regardless, to hammer home his view that women should primarily focus on their household and their children instead of engaging in any social activities. Apparently John Stuart Mill hated the character, thinking it was an attack by Dickens on women's rights.I think he has as many "negative" women - by his own lights - as men. He admired the Victorian ideal woman, didn't he, and made it very obvious. Docile, industrious, kind, intelligent, pretty (rather than what Victorians would call "handsome"), young (17 being the ideal ...). So characters like Edith Granger (view spoiler) never come across as wholly good, although we in our century admire them.

I'm now up to the end of chapter 7, and we've met Harold Skimpole, who is a delight to read about, just as Mrs. Jellyby has been. (view spoiler)

I'm now up to the end of chapter 7, and we've met Harold Skimpole, who is a delight to read about, just as Mrs. Jellyby has been. (view spoiler)Harold Skimpole:

Harold Skimpole was based on an actual author, Leigh Hunt, an English critic, essayist, poet, and writer, who continually sponged off his friends, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord George Gordon Byron. Charles Dickens himself wrote,

"I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words! ... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man"

and another contemporary critic commented,

"I recognised Skimpole instantaneously; ... and so did every person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt's acquaintance."

G.K. Chesterton oddly commented that Dickens,

"may never once have had the unfriendly thought, 'Suppose Hunt behaved like a rascal!'; he may have only had the fanciful thought, 'Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!'"

Another character who is named after a real person is not a human being at all but a cat!

Another character who is named after a real person is not a human being at all but a cat! Lady Jane:

Krook's cat is named after Lady Jane Grey who reigned as queen of England for a mere nine days in 1533. She was forced to abdicate, imprisoned, and eventually beheaded.

Odd, another reference to a different beheaded monarch in a Dickens novel, straight after David Copperfield, where (view spoiler).

Chapter 8 I found very hard to read. The bricklayer's house ... these scenes Dickens portrays are so very affecting. The dreadful Mrs Pardiggle with her,

Chapter 8 I found very hard to read. The bricklayer's house ... these scenes Dickens portrays are so very affecting. The dreadful Mrs Pardiggle with her,"rapacious benevolence (if I may use the expression)"

- What an oxymoron that is! I had thought Mrs Jellyby was bad, but this character is truly abominable :(

We need the lightheartedness of Guppy's (view spoiler) in chapter 9 to recover from chapter 8. What a master Dickens is, to balance and control our emotions this way!

In chapter 9 we meet Laurence Boythorn, a bluff hearty sort of chap, who is (view spoiler). And of course, he had a real-life counterpart...

Laurence Boythorn:

Laurence Boythorn:

Laurence Boythorn was based on Dickens's friend, Walter Savage Landor, an English writer and poet who was critically acclaimed but not very popular. Apparently his headstrong nature, hot-headed temperament, and complete contempt for authority, landed him in a great deal of trouble over the years. His writing was often libellous, and he was repeatedly involved in legal disputes with his neighbours. And yet Landor was described as,

"the kindest and gentlest of men".

Dickens has painted a fine picture of his friend Landor, in Laurence Boythorn!

And yet again there's a bird reference. Birds seem to crop up in Dickens all the time. Crows flying overhead are always ominous, there are endless references to birds in cages - present in most novels - and never more I think than in Bleak House.

I loved the description of Tulkinghorn, the man of secrets! He seems indistinguishable from his house - Dickens always seems to imbue his houses with human characteristics. In Tulkinghorn's home,

I loved the description of Tulkinghorn, the man of secrets! He seems indistinguishable from his house - Dickens always seems to imbue his houses with human characteristics. In Tulkinghorn's home,"everything that can have a lock has got one; no key is visible." He is,

"a great reservoir of confidences. His clients want him; he is all in all." And in the chambers of Tulkinghorn,

"In those shrunken fragments of greatness, lawyers lie like maggots in nuts".

Dickens has no love of the Law!

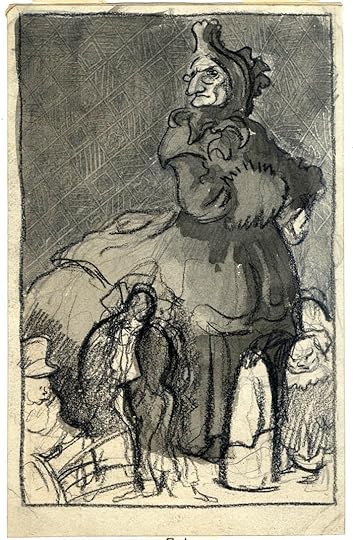

I've been thrilled to discover that Mervyn Peake did some illustrations for Bleak House! Of all Dickens's novels, this would be the one I would think fits his style best - it feels so Gormenghast- like in places! Since I recently tried hard to find Mervyn Peake's illustrations for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass, which I knew existed, but had mysteriously "disappeared " from the library, so it was a real bonus to find this out!

I've been thrilled to discover that Mervyn Peake did some illustrations for Bleak House! Of all Dickens's novels, this would be the one I would think fits his style best - it feels so Gormenghast- like in places! Since I recently tried hard to find Mervyn Peake's illustrations for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass, which I knew existed, but had mysteriously "disappeared " from the library, so it was a real bonus to find this out!Here are two:

Mrs Pardiggle and her children:

And Mr. Harold Skimpole:

Phiz drew a pretty near perfect illustration of how I see Mr. Guppy - a young whipper-snapper, a would-be dandy. There's a lot of Dickens himself in Mr. Guppy I think!

Phiz drew a pretty near perfect illustration of how I see Mr. Guppy - a young whipper-snapper, a would-be dandy. There's a lot of Dickens himself in Mr. Guppy I think!Much as I love Mervyn Peake's Art work, I don't think it represents the characters very well. I've looked at most of his illustrations for Bleak House, and they are all very much grotesques. I am wondering, having just read Paula Rego's take on Jane Eyre, whether an artist sometimes reinterprets what a book is saying to them personally, and produces a work of Art more to do with their own response, rather than an illustration which attempts to reproduce in another media, what the writer themself was trying to convey.

Now Charles Dickens would never have let Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz") get away with anything which he wanted to put in as a personal quirk! It had to be completely Dickens's own vision, and you can tell from his letters how very specific and inisistent he was about detail. (He must have been terrible to work with!)

You can analyse the symbolism in quite a few of Phiz's illustrations - birdcages and so on. I've been struck in this one by how often in the early illustrations Esther is pictured with her back to us. Given her early oppression, her unassuming modest nature (sometimes annoyingly seeming to protest her ineptitude rather too much!) this seems totally in keeping. We know she is plain too (rather like Jane Eyre in fact) and also there is an element of mystery about her visage, and possibly a hint of foretelling about this as well. It's very clever :)

But back to Mervyn Peake, and I definitely want to track Sketches From Bleak House down, though I will view it as images inspired by Bleak House, rather than anything else.

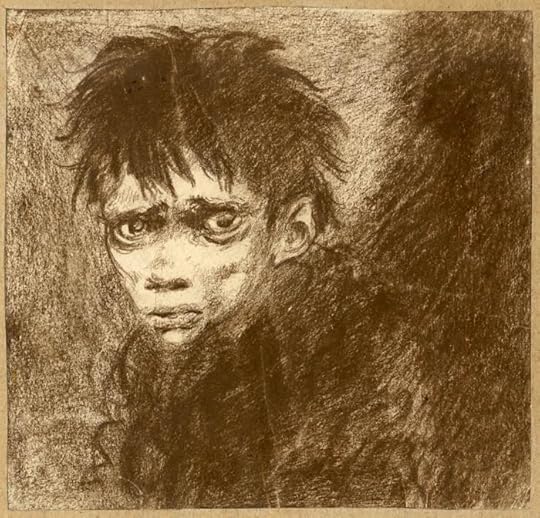

I've just finished chapter 11 - and met poor Jo, the crossing sweeper, who always makes me want to cry with his plaintive,

I've just finished chapter 11 - and met poor Jo, the crossing sweeper, who always makes me want to cry with his plaintive, "He was wery good to me, he wos!"

And I do like Mervyn Peake's depiction of Jo, which is exactly how I picture him too :)

And what do you know - Jo the crossing sweeper, who has "No father, no mother, no friends" was also quite incredibly based on a real person!

And what do you know - Jo the crossing sweeper, who has "No father, no mother, no friends" was also quite incredibly based on a real person!One of Charles Dickens's children, Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens (his sixth child) used to lecture all over the world on his father's life and work. This is what he said, in a contemporary magazine, "Nash's":

"Shortly after my father had taken up his residence at Tavistock House there appeared upon the scene a crossing sweeper in the shape of a small boy. He was about fourteen years of age, and was, I firmly believe, the original of poor Joe in "Bleak House" which was written, as many of my readers may recollect, in 1852. The boy-sweep made these houses his headquarters, keeping the pavements and drive scrupulously clean... After a time an intimacy sprang up between my father and the neglected lad, and Dickens finding the boy honest, industrious, and intelligent, saw to it that the little chap got his meals in the kitchen of Tavistock House, and sent him to school at night. The boy got on wonderfully well with his education, and when he came to be some seventeen years of age his benefactor procured for him a substantial outfit and sent him to the colony of New South Wales. It is satisfactory to know that the young man prospered well in his adopted country. After he had been in Australia some three years he wrote to his friend in England, thanking him for his kindness and telling him of his prosperity."

I just love the contrast between the two great folk. "My Lady" Dedlock with her constant complaints of being "bored to death"; her general fatigue and ennui. The poor thing is apparently exhausted after reading for 20 minutes (or is it pages?) ... and then there's this wonderful description of Sir Leicester Dedlock:

I just love the contrast between the two great folk. "My Lady" Dedlock with her constant complaints of being "bored to death"; her general fatigue and ennui. The poor thing is apparently exhausted after reading for 20 minutes (or is it pages?) ... and then there's this wonderful description of Sir Leicester Dedlock:"Sir Leicester is generally in a complacent state, and rarely bored. When he has nothing else to do, he can always contemplate his own greatness. It is a considerable advantage to a man to have so inexhaustible a subject. After reading his letters, he leans back in his corner of the carriage and generally reviews his importance to society."

Jo the crossing sweeper is one of Dickens's most heart-breaking characters for me, always being "moved on" and not having a clue why, or whether there might actually be somewhere he could go to. It's not even the ignorance or social injustice so much, but the lad's total incomprehension somehow ...

Jo the crossing sweeper is one of Dickens's most heart-breaking characters for me, always being "moved on" and not having a clue why, or whether there might actually be somewhere he could go to. It's not even the ignorance or social injustice so much, but the lad's total incomprehension somehow ...

The description of the graveyard might sounds so horrific as to be Charles Dickens indulging in a bit of melodrama, but in this case I don't think he was. In The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, which I read recently, she described how the massive surge in population had meant that graveyards started with holes dug in the ground for corpses, but very soon they ran out of room and they just stacked them up, one on top of another, so that you had to look up to "ground" level. And here is a description from Death, Heaven, and the Victorians. by John Morley:

The description of the graveyard might sounds so horrific as to be Charles Dickens indulging in a bit of melodrama, but in this case I don't think he was. In The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, which I read recently, she described how the massive surge in population had meant that graveyards started with holes dug in the ground for corpses, but very soon they ran out of room and they just stacked them up, one on top of another, so that you had to look up to "ground" level. And here is a description from Death, Heaven, and the Victorians. by John Morley: Overcrowded churchyards meant that recently interred corpses were constantly disturbed; it was this that made the system of interment a "gross indecency towards the dead". In order to make room, corpses not a week buried were chopped up and burnt; choppers and saws for the purpose were kept in the graveyards. There was frequently a charnel house or 'bone house' in the churchyard...A grave-digger [in] 1842 told a hair-raising story of how the corpse of a woman, from which the head had been chopped, fell on him in the dark from the side of a grave he was digging. The grave-diggers stole lead from the coffins, and sold the bodies to surgeons; sextons were impelled to dispose of as many bodies as possible, since the more that were buried, the greater the profit."

The nature of infectious disease was not yet properly understood. Dickens mentions the visitor to the graveyard having: "deadly stains contaminating her dress". Doctors of the time thought that diseases such as cholera, typhus, and typhoid travelled throught the air. In 1854, John Snow asserted that some of the most serious diseases, such as cholera, had a direct relation to water. He persuaded officials to put a lock on the pump that supplied water to one particular district of London, and the cholera declined.

"Pasteur's germ theory of disease did not take hold until the last third of the century, and Robert Koch did not isolate the anthrax micro-organism until 1876, the tuberculosis bacillus until 1882, and that for cholera until two years after that. Pasteur, who began experimenting with fermentation in the late 1850s, did not produce his hydrophobia vaccine until 1885. Dickens's readers, therefore, both found little if any exaggeration in his description of the cemetery and well understood his notion of the dangers of visiting foul ground that gave of vile odours."

The stench must have been unimaginable :(

Sticking to this episode, there is a famous oil painting depicting Jo and a wealthy woman (whom we may or may not know, depending on how far we are on in the book!) from 1858 by William Powell Frith. Here it is:

Sticking to this episode, there is a famous oil painting depicting Jo and a wealthy woman (whom we may or may not know, depending on how far we are on in the book!) from 1858 by William Powell Frith. Here it is:

It became so well-known that Frith updated the fashions every few years in the 1890's! Here's a later one:

It has been said that it "breaks new ground in its description of the collision of wealth and poverty on a London street".

This famous portrait of Charles Dickens in middle age is also by William Powell Frith:

We've had so much about death so far in this novel. I've counted 4 so far. And although we have delightfully droll passages, there are no outright villains of the piece yet - nobody to shudder at like Quilp, or Wackford Squeers - or even Saul Pecksniff!

We've had so much about death so far in this novel. I've counted 4 so far. And although we have delightfully droll passages, there are no outright villains of the piece yet - nobody to shudder at like Quilp, or Wackford Squeers - or even Saul Pecksniff!Everyone seems to be trapped like Miss Flite's birds. Oh their names ... initially using positive terms: "Hope, Joy, Youth, Peace, Rest" but rapidly descending to "Dust, Ashes, Waste, Want...". So many of these are themes or motifs coming through in this book!

The biggest group of prisoners by far are the children, who are trapped in their differing circumstances. There's Jo's grinding poverty and ignorance, Charlie as a drudge and a slave for her mother the philanthropist Mrs. Jellyby - and the appallingly (but understandably) selfish children of her "philanthropic" friend Mrs. Pardiggle. Even Esther's own childhood was restricted and trapped.

Miss Flite's caged birds are a symbol of both the court case and everyone who is trapped and imprisoned by their own circumstances. For instance Price Turveydrop's father is trapped by his own deportment, so that he can't sit down properly! Esther says,

"As he bowed to me in that tight state, I almost believe I saw creases come into the whites of his eyes."

Even Sir Leicester Dedlock seems thoroughly "locked" in his "respectability".

Mademoiselle Hortense:

in chapter 18

Mademoiselle Hortense:

in chapter 18Lady Dedlock's maid, Hortense is one of Dickens's amazingly powerful females - like an early version of Madame Defarge in A Tale of Two Cities with all that passion, outrage and talk of blood. It puts me in mind of the story of the Ghost of Chesney Wold. The footsteps, haunting, blood, ghosts, thunderstorms, faces...it's all beginning to feel a bit Gothic. Are these portents? We already have the mystery and the atmosphere. Here the other characters are talking about her:

"But she's mortal high and passionate—powerful high and passionate; and what with having notice to leave, and having others put above her, she don't take kindly to it."

"But why should she walk shoeless through all that water?" said my guardian.

"Why, indeed, sir, unless it is to cool her down!" said the man.

"Or unless she fancies it's blood," said the woman. "She'd as soon walk through that as anything else, I think, when her own's up!"

Apparently Hortense was modelled on a real-life Swiss lady's maid, Maria Manning. Maria Manning and her husband were convicted of the murder of Maria's lover, Patrick O'Connor, in a case which became known as "The Bermondsey Horror."

The couple had invited Patrick O'Connor to dinner, and murdered him so that they could steal his railway shares and money. They then buried his body under the flagstones in the kitchen. It looks as though they had also been planning to double cross each other. They were executed in 1849, the first time a husband and wife had been executed together in England since 1700.

Charles Dickens witnessed the execution, and wrote a letter to The Times about it:

"the wickedness and levity of the mob...the shrillness of the cries and howls that were raised from time to time, denoting that they came from a concourse of boys and girls already assembled in the best places, made my blood run cold...every variety of offensive and foul behaviour... inexpressibly odious in their brutal mirth or callousness".

In The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins also referred to this notorious crime, when commenting on the fat villain Count Fosco:

"Mr. Murderer and Mrs. Murderess Manning were not both unusually stout people?"

We're getting yet more characters introduced ... Dickens was asking quite a lot of his original readers, who could only read one episode every month. Anyway, I'm now picking up on another theme in the book - that a person’s character is determined up to a point by their upbringing.

We're getting yet more characters introduced ... Dickens was asking quite a lot of his original readers, who could only read one episode every month. Anyway, I'm now picking up on another theme in the book - that a person’s character is determined up to a point by their upbringing. The Smallweeds are another grotesque family of caricatures - similar to the self-righteous Mrs. Pardiggle and her obnoxious children. Grandfather Smallweed is a very old man confined to a chair (and probably sitting on a large sum of money). He's a tight-fisted money-lender, and behaves so badly that his wife is permanently panicked by any mention of money, starting up at any figure mentioned and going on about it so that Grandfather Smallweed throws his cushion at her, silencing her for the time being and reducing himself to a bundle of clothes that has to be shaken up.

It's very funny of course, but look what has happened to the grandchildren, Judy and Bart. They aren't really children at all, and don't know how to play. Does the reader feel dislike or pity here?

We also meet Mr. Guppy's friend Mr. Jobling, and Mr. George, the owner of a shooting gallery, who has a connection with Captain Hawdon. He describes remaining by Hawdon's side through his ruin, when "sick and well, rich and poor". Then another character - Inspector Bucket, who is a detective.

We also meet Mr. Guppy's friend Mr. Jobling, and Mr. George, the owner of a shooting gallery, who has a connection with Captain Hawdon. He describes remaining by Hawdon's side through his ruin, when "sick and well, rich and poor". Then another character - Inspector Bucket, who is a detective. "Yet this third person stands there with his attentive face, and his hat and stick in his hands, and his hands behind him, a composed and quiet listener. He is a stoutly built, steady-looking, sharp-eyed man in black, of about the middle-age. Except that he looks at Mr. Snagsby as if he were going to take his portrait, there is nothing remarkable about him at first sight but his ghostly manner of appearing."

The character of Inspector Bucket is the first ever portrayal of a detective in English fiction. Dickens based him on the real-life Inspector Charles Frederick Field, about whom he had written three articles in "Household Words" in August and September 1850.

Here's Charles Field, from an engraving in 1855:

I'm at chapter 23 now, and I hope we can go back to some familiar faces for a bit!

"Dickensian" is a TV series I'm engrossed in at the moment. From Bleak House it features Lady Honoria Dedlock (view spoiler), Frances Barbary, Captain Hawdon and Inspector Bucket - plus a host of other characters from some of the other novels, all very cleverly interwoven.

"Dickensian" is a TV series I'm engrossed in at the moment. From Bleak House it features Lady Honoria Dedlock (view spoiler), Frances Barbary, Captain Hawdon and Inspector Bucket - plus a host of other characters from some of the other novels, all very cleverly interwoven. All seem to keep their authentic characters, and it serves as a prequel to several novels. Part of the fun is in identifying who each character is, and where they are from. It's really cleverly written as a mystery, with Inspector Bucket as the main character.

I had great reservations when I heard it was being made, but it's actually very good, in my opinion. I hope those outside the UK get the chance to see it.

Link here

OK - if you have no idea why I have posted that image, and have not yet reached chapter 32, or are browsing and think you might read Bleak House some time in the future, then please do not click on the spoilers in the next 3 posts!

(view spoiler)

(view spoiler)And so it carries on until there is no doubt whatsoever by the closing words of the chapter. *shudders*

Bleak House is a much darker book overall I'm finding, with far fewer comic portraits. Lots of motifs such as birds - often imprisoned, covered faces - Esther's face is usually turned away in illustrations (we now know why that might be), children - there are so many different children in this book even to the child-like adults, but they are all damaged in some way, "Bleak House" possibly describing several houses - but not actually the one which bears its name, chancery- and the parallels of chancery with Krook. So, so many layers.

Bleak House is a much darker book overall I'm finding, with far fewer comic portraits. Lots of motifs such as birds - often imprisoned, covered faces - Esther's face is usually turned away in illustrations (we now know why that might be), children - there are so many different children in this book even to the child-like adults, but they are all damaged in some way, "Bleak House" possibly describing several houses - but not actually the one which bears its name, chancery- and the parallels of chancery with Krook. So, so many layers. I'm wondering if the lack of laugh-out-loud humour is partly due to Dickens's own state of mind. Here's a bit from John Forster's biography, referring to just after the first issue in 1842:

"At this date it seemed to me that the overstrain of attempting too much, brought upon him by the necessities of his weekly periodical, became first apparent in Dickens. Not infrequently a complaint strange upon his lips fell from him. "Hypochondriacal whisperings tell me that I am rather overworked. The spring does not seem to fly back again directly, as it always did when I put my own work aside, and had nothing else to do. Yet I have everything to keep me going with a brave heart, Heaven knows!" Courage and hopefulness he might well derive from the increasing sale of Bleak House, which had risen to nearly forty thousand; but he could no longer bear easily what he carried so lightly of old, and enjoyments with work were too much for him. "What with Bleak House, and Household Words, and Child's History" (he dictated from week to week the papers which formed that little book, and cannot be said to have quite hit the mark with it), "and Miss Coutts's Home, and the invitations to feasts and festivals, I really feel as if my head would split like a fired shell if I remained here."

By "here", I think meant away from his new home, Tavistock House, where he had moved to at the end of the previous November. But since then he had been on tour with his theatre company, and by the end of the novel he was in Boulogne. I don't know how he settled to anything really, and it rather sounds as though he himself was beginning to wonder.

Harold Skimpole is very disagreeable. A sort of antithesis of Mr. Dick in David Copperfield, who is a genuine naif. I'm never really sure why John Jarndyce is taken in by him. Perhaps the point is to show how incredible good, but gullible, Jarndyce is.

Harold Skimpole is very disagreeable. A sort of antithesis of Mr. Dick in David Copperfield, who is a genuine naif. I'm never really sure why John Jarndyce is taken in by him. Perhaps the point is to show how incredible good, but gullible, Jarndyce is.

Which house can be described as a "Bleak House"? There are several candidates - but not the one which is actually named "Bleak House". I wonder what Dickens was referring to with this title. His titles often seem to be not what they at first appear, such as Martin Chuzzlewit, which does not refer to the character (the son) whom the reader first expects.

Which house can be described as a "Bleak House"? There are several candidates - but not the one which is actually named "Bleak House". I wonder what Dickens was referring to with this title. His titles often seem to be not what they at first appear, such as Martin Chuzzlewit, which does not refer to the character (the son) whom the reader first expects.I was interested to learn that Dickens used "Tom-All-Alone's" as a working title for Bleak House, which seems to indicate that out of all the many themes in this book, the paramount one in his mind was his hatred of the London slums. Dickens loathed both the despicable conditions there, and the governmental practices which allowed them to exist. He tirelessly campaigned for their improvement.

But the name "Tom" rang a bell, as one of the original characters in the Jarndyce v. Jarndyce" lawsuit was named "Tom". (He was the one who apparently shot himself.) So are we to gather from this, that "Tom-All-Alone's" - that decrepit slum - was the original property tied up in the case? We've had several indications that such lengthy court cases lead to despair and ruin. Nobody knew who owned such properties; it is never resolved. Surely they would never be maintained, and gradually just fall into ruin.

People were losing their minds over an unresolved court case which dragged on without end, and the crumbling buildings seem to reflect this.

When I was reading The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, there was a lot about the slums, and the fact that a modern sewer system had yet to be implemented, despite the fact that the city of London had suddenly and massively increased in population.

When I was reading The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, there was a lot about the slums, and the fact that a modern sewer system had yet to be implemented, despite the fact that the city of London had suddenly and massively increased in population.The well to do had no idea of the conditions the poor were living in. I remember reading of one case where the rich neighbouring borough hated the stench of the one single toilet, which served a courtyard with many families (almost unimaginably, several to each room) all dependent on it. They objected, and it was pulled down! Unbelievable! So the poor then had nowhere to defecate at all, except for the street or the river Thames.

From the "Victorian Web", here's a letter sent to "The Times" newspaper. It was published on July 5, 1849, just a couple of years before Bleak House started to be serialised, under the headline "A Sanitary Remonstrance":

THE EDITUR OF THE TIMES PAPER

Sur, — May we beg and beseech your proteckshion and power. We are Sur, as it may be, livin in a Wilderniss, so far as the rest of London knows anything of us, or as the rich and great people care about. We live in muck and filth. We aint got no priviz, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place. The Suer Company, in Greek St., Soho Square, all great, rich and powerfool men, take no notice watsomdever of our complaints. The Stenche of a Gully-hole is disgustin. We all of us suffer, and numbers are ill, and if the Colera comes Lord help us.

Some gentlemans comed yesterday, and we thought they was comishioners from the Suer Company, but they was complaining of the noosance and stenche our lanes and corts was to them in New Oxforde Strect. They was much surprized to see the seller in No. 12, Carrier St., in our lane, where a child was dyin from fever, and would not believe that Sixty persons sleep in it every night. This here seller you couldent swing a cat in, and the rent is five shillings a week; but theare are greate many sich deare sellars. Sur, we hope you will let us have our complaints put into your hinfluenshall paper, and make these landlords of our houses and these comishioners (the friends we spose of the landlords) make our houses decent for Christions to live in. Preaye Sir com and see us, for we are living like piggs, and it aint faire we shoulde be so ill treted.

We are your respeckfull servents in Church Lane, Carrier St., and the other corts. Teusday, Juley 3, 1849.

The letter was then completed with the signatures of all fifty-four slum-dwellers.

And this is not fiction.

By the end of chapter 48 we have had 8 deaths in Bleak House, during the course of the novel so far! (view spoiler)

By the end of chapter 48 we have had 8 deaths in Bleak House, during the course of the novel so far! (view spoiler)These last two were in successive chapters - unusual for Dickens who tend to gives us ludicrously light relief after an emotional part like this. But ... perhaps we are not too traumatised by the death of the eighth character? Or perhaps the seventh and eighth are deliberately juxtaposed like this, being at opposite ends of the social spectrum - and in fact opposites in every way. Poor v. rich, ignorant and honest v. cunning and devious. It seems likely to be pointed, since they died on the same day.

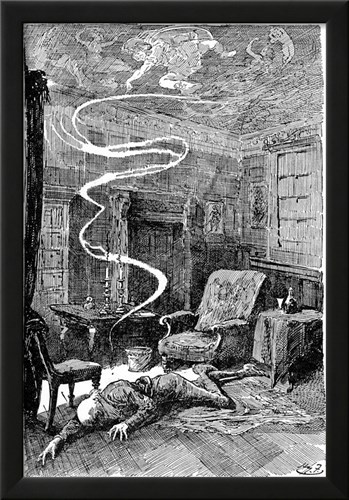

I usually prefer Phiz's illustrations to anyone else's, but I do like this illustration of (view spoiler), with "Allegory" and the pointing finger, which the text has often mentioned before. The artist is Henry Furniss, in 1912:

I usually prefer Phiz's illustrations to anyone else's, but I do like this illustration of (view spoiler), with "Allegory" and the pointing finger, which the text has often mentioned before. The artist is Henry Furniss, in 1912:

"For many years the persistent Roman has been pointing, with no particular meaning, from that ceiling...But a little after the coming of the day...either the Roman has some new meaning in him, not expressed before, or the foremost of them goes wild, for looking up at his outstretched hand and looking down at what is below it, that person shrieks and flies. The others, looking in as the first one looked, shriek and fly too, and there is an alarm in the street. All eyes look up at the Roman, and all voices murmur, "If he could only tell what he saw!"

He is pointing at a table with a bottle (nearly full of wine) and a glass upon it and two candles that were blown out suddenly soon after being lighted. He is pointing at an empty chair and at a stain upon the ground before it that might be almost covered with a hand. These objects lie directly within his range...It happens surely that every one who comes into the darkened room and looks at these things looks up at the Roman and that he is invested in all eyes with mystery and awe, as if he were a paralysed dumb witness...

For (view spoiler) time is over for evermore, and the Roman pointed at the murderous hand uplifted against his life, and pointed helplessly at him, from night to morning, lying face downward on the floor, shot through the heart."

Thinking back over the characters who have (view spoiler)

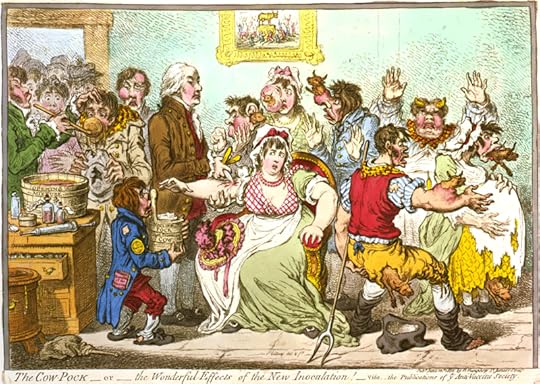

Thinking back over the characters who have (view spoiler)There were vaccinations available at that time,

Edward Jenner, an English country doctor in the late 1700s, found that smallpox was one of the most common and worst problems he encountered. Many of his patients were cattle farmers. In 1788, an epidemic hit the small town, and he noticed that the cattle farmers among his patients were not dying from smallpox. The only treatment available so far, was to inoculate healthy people with the liquid from the pustules of people with mild cases of the disease. (YUK!) This only worked sometimes. Jenner wondered if it was the similar cowpox which had been protecting the farmers, and tried an experiment.

In 1796 Edward Jenner carefully extracted some liquid from the cowpox sores a young milkmaid had developed on her hands. He then approached a local farmer and asked if he could inoculate his son with the cowpox, on the grounds that if he was right, the boy would never catch smallpox. Rather incredibly, the farmer agreed. The boy did get cowpox, but made a complete recovery, whereupon Edward Jenner then injected him with liquid from smallpox pustules. Sure enough the boy did not get smallpox and Jenner had proved his theory.

This discovery of vaccination came before people knew about viruses, or much about the immune system. The general public and other doctors were very sceptical, but he persisted in spite of all the resistance.

In 1802 James Gillray made a caricature "The Cow Pock - or the Wonderful Effect of the New Inoculation" making fun of his theory, and playing on people's fears. It shows people developing cow parts after vaccination. Here it is,

'The Cow Pock or the wonderful effect of the new inoculation '. From an etching by James Gillray (1757-1815), illustrating some of the ridiculous ideas being circulated by opponents of Jenner's work

I'm up to chapter 60 now - so many disguises in this book - I can see why its thought to be a mystery. And I'm loving Inspector Bucket's astuteness; he's a forerunner of Hercule Poirot to be sure! And the way he says wryly "Sir Leicester Dedlock - Baronet", giving him his full title every single time LOL!

I'm up to chapter 60 now - so many disguises in this book - I can see why its thought to be a mystery. And I'm loving Inspector Bucket's astuteness; he's a forerunner of Hercule Poirot to be sure! And the way he says wryly "Sir Leicester Dedlock - Baronet", giving him his full title every single time LOL!I make the body count 10.

(view spoiler)

I like Inspector Bucket. He seems more solid and believable even than Esther! Sometimes I think the lady doth protest (her humility) too much... Perhaps there's a reason she's Dickens's only female narrator.

I like Inspector Bucket. He seems more solid and believable even than Esther! Sometimes I think the lady doth protest (her humility) too much... Perhaps there's a reason she's Dickens's only female narrator.

Original Dates of publication in "Household Words" (equivalent to the Chapters in the novel)

Original Dates of publication in "Household Words" (equivalent to the Chapters in the novel)Book I

1 April 1854 1–3

8 April 1854 4–5

15 April 1854 6

22 April 1854 7–8

29 April 1854 9–10

6 May 1854 11–12

13 May 1854 13–14

20 May 1854 15–16

Book II

27 May 1854 17

3 June 1854 18–19

10 June 1854 20–21

17 June 1854 22

24 June 1854 23

1 July 1854 24

8 July 1854 25–26

15 July 1854 27–28

22 July 1854 29–30

Book III

29 July 1854 31–32

5 August 1854 33–34

12 August 1854 35–37

HARD TIMES

HARD TIMESWhat I immediately noticed, is the comparative brevity. Not only is it a short novel, but the first chapter is only about a page long - equivalent to one sentence by Dickens in some others! The writing is much snappier - sometimes over-emphasising things for humour. It feels so totally different from Bleak House that I had to find out what was in his mind.

It turns out that instead of publishing monthly parts, so with Bleak House for instance, readers had no option but to read it over a year and a half in the first instance, Hard Times was published weekly, the whole being over a mere five months! Plus each installment was shorter - the chapters were shorter, and if you look at the original publishing schedule, which I'll post in the next comment, sometimes there was only one chapter published that week!

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

I do love Micawber's over-elaboration, pomposity and wordiness! I think non-native English-speaking readers of Dickens must find him a bit of a trial though, unless they are exceptionally fluent.

Actually I'm finding what I called the "hints" - and the foreboding - very marked in this novel. I suppose that shows how well planned the main features were.