The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 01-03

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Engraved title-page: At the Finger Post

Phiz

July 1844

Instructions from Dickens to Phiz. re. Vignette for Title Page

The finger post at the end of the lane, which has been so often mentioned. You can either have Tom Pinch waiting with John Westlock and his boxes, as at the opening of the book; or Mr. Pecksniff blandly receiving a new pupil from the coach (perhaps this will be better); and by no means forgetting the premium in his welcome of the Young Gentleman. Will you let me see the Designs for these two?

Michael Steig in the third chapter of Dickens and Phiz notes that the title-page vignette contains some ambiguities in using the fingerpost as an emblem of a young man's setting out to find his place in the world:

Note how Dickens arrives at the subject: he knows that he wants the fingerpost as an emblematic focus, and after considering a specific scene from the novel decides that he prefers one which does not occur in the book and is an epitome rather than a pure a illustration. Browne's rendering of the subject provides meanings which are not specified in these directions. First, the fingerpost itself is broken — specifically the board pointing in the direction from which Pecksniff has come, implying that to follow him is to go nowhere, and also recalling the description of Pecksniff as a "direction post" which "never goes there" (ch. 2, p. 10). Upon the post is a sign reading "£100 Reward" (or in the drawing and one steel, "100£," a matter of some moment to collectors), which alludes to the premium demanded, and to the criminal, because fraudulent, nature of Pecksniff's dealings with his pupils.

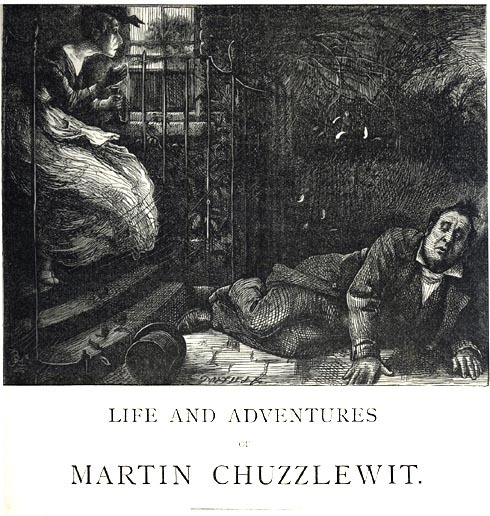

Uncaptioned illustration to begin Chapter One, page 1.

Fred Barnard

1872

Commentary:

Fred Barnard's narrative-pictorial sequence for the thirty-year-old picaresque novel begins earlier than Phiz's. The chief illustrator of the Household Edition begins, as it were, almost at the beginning, immediately after the rambling, almost Swiftian Chuzzlewit genealogy of the opening chapter. For this, the story's first comic scene, Barnard prepares the reader a full chapter in advance, seizing upon the most engaging moment with which to lead off his pictorial sequence and introduce his Tartuffian antagonist, architect Seth Pecksniff.

An undignified, partly stunned Seth Pecksniff has just been knocked off his feet at his own front-door steps by the boisterous Wiltshire wind, and his daughter, shading her candle, unable to discern his prostrate figure on the ground in the darkness, is operating under the delusion that she is the victim of some practical-joking street-boy who, having knocked, has ducked around the corner to observe the fun from hiding. Realizing the text's first piece of real action, the uncaptioned woodcut sits above the opening of the first chapter but pertains to the second.

Dressed in the respectable garb of the English bourgeoisie circa 1840, in tailcoat, collar, his immaculate beaver lying by his feet, Pecksniff struggles to get up on his left elbow. This attire Barnard has borrowed directly from Phiz's early illustrations for the novel, notably "Pleasant little family party at Mr. Pecksniff's." Whereas Phiz's initial Pecksniff plates depict the antagonist as a self-satisfied and collected hypocrite, Barnard cannot resist the comic possibilities of the novel's opening scene, in which the usually loquacious architect has been momentarily stunned into speechlessness by his fall. As in the text, his daughter shields her candle from the raging wind which scatters leaves above her parent, whom she cannot see in the dusk. Instead of the brass knob on the street-door, Barnard focuses on the wrought- iron railings which connect Miss Pecksniff at the top of the stairs, her skirt and apron blowing vigorously towards stage left and her fallen father. Rather than struggle with the pictorial impossibilities of the first chapter, Barnard has utilized this key page in the text to introduce the self-important humbug Pecksniff.

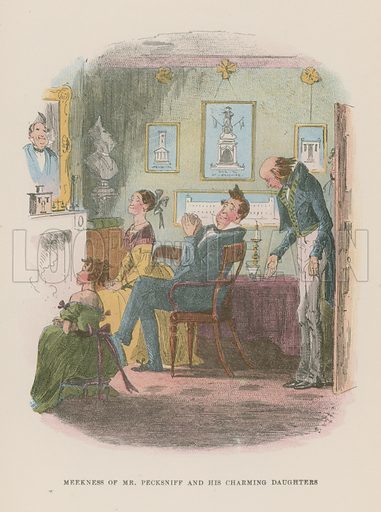

Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters

Chapter 2

Phiz

January 1843

Text Illustrated:

"Come in!" cried Mr. Pecksniff — not severely; only virtuously. "Come in!"

An ungainly, awkward-looking man, extremely short-sighted, and prematurely bald, availed himself of this permission; and seeing that Mr Pecksniff sat with his back towards him, gazing at the fire, stood hesitating, with the door in his hand. He was far from handsome certainly; and was drest in a snuff-coloured suit, of an uncouth make at the best, which, being shrunk with long wear, was twisted and tortured into all kinds of odd shapes; but notwithstanding his attire, and his clumsy figure, which a great stoop in his shoulders, and a ludicrous habit he had of thrusting his head forward, by no means redeemed, one would not have been disposed (unless Mr Pecksniff said so) to consider him a bad fellow by any means. He was perhaps about thirty, but he might have been almost any age between sixteen and sixty; being one of those strange creatures who never decline into an ancient appearance, but look their oldest when they are very young, and get it over at once.

Keeping his hand upon the lock of the door, he glanced from Mr. Pecksniff to Mercy, from Mercy to Charity, and from Charity to Mr Pecksniff again, several times; but the young ladies being as intent upon the fire as their father was, and neither of the three taking any notice of him, he was fain to say, at last,

"Oh! I beg your pardon, Mr Pecksniff: I beg your pardon for intruding; but —"

"No intrusion, Mr. Pinch," said that gentleman very sweetly, but without looking round. "Pray be seated, Mr. Pinch. Have the goodness to shut the door, Mr. Pinch, if you please." [Chapter II, "Wherein become better acquainted," page 14 in the 1844 edition; descriptive headline: "Mr. Westlock" (1897).]

Commentary: Making Egotism Entertaining

Since the January instalment in fact went on sale in late December, we may reasonably assume that Browne executed the accompanying pair of etchings as triplicate steels in early December after reading the first three chapters in proof. Already we see evidence of the illustrator's providing embedded details that make Pecksniff readily identifiable throughout the sequence by virtue of his rectangular head, puritanical habiliments, and spiky hair — prounced features that such later illustrators as Eytinge, Barnard, and Furniss felt bound to maintain in their depictions of the arch-hypocrite. Phiz has derived the "two jutting heights of collar," the grizzled, "bolt upright" tonsorial crown, and languid eyelids directly from Dickens's initial description of the village architect and professional mentor of such budding apprentices as John Westlock and Tom Pinch. The text mentions the furnishings of the room, particularly the bust and portrait of Pecksniff, as well as the "frizzled" hair of the younger Miss Pecksniff. But whereas Dickens describes the girl's hair in Chapter 2, he does not describe the Spiller portrait and Spoker bust until Chapter 5 in the second monthly part, so that these emblematic details may well have originated with Phiz. Indeed, Fred Barnard in the frontispiece to the 1872 Household Edition deemed these details so revealing of Pecksniff's egotism that he developed a scene in which the architect is admiring his own bust, as if regarding himself in a mirror.

The moment illustrated seems to be when Tom Pinch, stooping before the potentate, has opened the parlour door and tentatively entered, leaving John Westlock on the threshold as Tom attempts to make peace between former master and former pupil. With his rake-like figure and prematurely balding pate, Tom Pinch appears exactly as Dickens describes him (Penguin p. 68-70). The architectural studies hanging on the wall, however, were merely suggested to Phiz by the author's mentioning the kinds of architectural studies Pecksniff habitually sets his apprentices: "Public Buildings." The study immediately behind Pecksniff's head looks very much like a workhouse, factory, or prison block, all of which identifications are suggestive of his treatment of Westlock and Pinch. Akin to their father's self-satisfaction and lack of conscience about his callous exploitation of these young men's talents are the sisters' complacent expressions, their half-shut eyes mirroring exactly their father's.

The Latin motto beneath a framed picture of a monument, "Pecksniff Fecit," implies the master-architect's conception of himself as another Marcus Agrippa, the trusted architectural second-in-command of Augustus Caesar who, having achieved victory at Actium, determined to transform Rome's buildings from brick to marble, his chief architectural legacy being the splendid Pantheon, there may also be an English pun, implying Pecksniff's duplicity. From this plate onward we associate the number three with Pecksniff, as if he is the head of a trinity, his daughters being his complements as a three-personed deity. Michael Steig in his article "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz" notes the Hogarthian detailing for which Phiz had become renowned. The poor box and pair of scales on the mantelpiece imply that the apparent benevolence and virtue of the Pecksniff trio is nicely calculated and hardly altruistic. A self-serving hypocrite in image as in letterpress, Pecksniff almost applauds himself as his finger-tips touch, supremely self-confident and unflappable, even when confronted by one who is quite undeceived: former pupil John Westlock, whose presence is implied only by the open door. The only Charity and Mercy, however, that Westlock encounters are the ironically named daughters.

Mr. Pecksniff and his Daughters

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Diamond Edition)

Commentary:

This second full-page character study introduces the story's arch-hypocrite, Seth Pecksniff, a widower and architect living in a village not far from Salisbury. Portraiture was high on the Royal Academy scale, and Eytinge has used the academician's trick of conveying the characters of the sitters through their faces, postures, and juxtapositions, showing their close affinity but subtle personality differences.

As members of a single family, the sitters all bear considerable resemblance to one another, but Pa's favourite (as signified by his gesture of patting her on the head) is the far more comely younger sister, Mercy, whose charming, free-flowing locks the illustrator has captured most effectively. Charity is of a different physical and psychological cast entirely: plain, discontented, and somewhat morose. And between the standing Charity and the sitting Mercy is enthroned Seth Pecksniff, a portrait derived from Phiz's original Martin Chuzzlewit serial illustrations, particularly "Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and His Chaming Daughters" (January 1843). As in Phiz's series, we should associate the number three with Pecksniff, as if he is the head of a trinity, his daughters being his complements as a three-personed deity and divine patron of the family parlour, which here is missing all those facetious details that in Phiz's original illustration represent Seth Pecksniff's egocentricity. The passage that we should regard as connected with the family portrait is this:

Mr. Pecksniff having been comforted internally, with some stiff brandy-and-water, the eldest Miss Pecksniff sat down to make the tea, which was all ready. In the meantime the youngest Miss Pecksniff brought from the kitchen a smoking dish of ham and eggs, and, setting the same before her father, took up her station on a low stool at his feet; thereby bringing her eyes on a level with the teaboard.

It must not be inferred from this position of humility, that the youngest Miss Pecksniff was so young as to be, as one may say, forced to sit upon a stool, by reason of the shortness of her legs. Miss Pecksniff sat upon a stool because of her simplicity and innocence, which were very great, — very great. Miss Pecksniff sat upon a stool because she was all girlishness, and playfulness, and wildness, and kittenish buoyancy. She was the most arch and at the same time the most artless creature, was the youngest Miss Pecksniff, that you can possibly imagine. It was her great charm. She was too fresh and guileless, and too full of child-like vivacity, was the youngest Miss Pecksniff, to wear combs in her hair, or to turn it up, or to frizzle it, or braid it. She wore it in a crop, a loosely flowing crop, which had so many rows of curls in it, that the top row was only one curl. Moderately buxom was her shape, and quite womanly too; but sometimes — yes, sometimes — she even wore a pinafore; and how charming that was! Oh! she was indeed "a gushing thing" (as a young gentleman had observed in verse, in the Poet's Corner of a provincial newspaper), was the youngest Miss Pecksniff!

Mr. Pecksniff was a moral man — a grave man, a man of noble sentiments and speech — and he had had her christened Mercy. Mercy! oh, what a charming name for such a pure-souled being as the youngest Miss Pecksniff! Her sister's name was Charity. There was a good thing! Mercy and Charity! And Charity, with her fine strong sense and her mild, yet not reproachful gravity, was so well named, and did so well set off and illustrate her sister! What a pleasant sight was that the contrast they presented; to see each loved and loving one sympathizing with, and devoted to, and leaning on, and yet correcting and counter-checking, and, as it were, antidoting, the other! To behold each damsel in her very admiration of her sister, setting up in business for herself on an entirely different principle, and announcing no connection with over-the-way, and if the quality of goods at that establishment don't please you, you are respectfully invited to favour ME with a call! And the crowning circumstance of the whole delightful catalogue was, that both the fair creatures were so utterly unconscious of all this! They had no idea of it. They no more thought or dreamed of it than Mr. Pecksniff did. Nature played them off against each other; they had no hand in it, the two Miss Pecksniffs.

Martin Chuzzlewit Suspects the Landlady Without Any Reason

Chapter 3

Phiz

January 1843

Commentary:

Made inveterately suspicious of others' motives by years of being pursued by his greedy relatives, Old Martin exhibits deep mistrust of the kindly Mrs. Lupin, hostess of the Blue Dragon Inn. The illustration of Mary Graham (right), Old Martin (centre), and the Widow Lupin (left) in old man's bedchamber at the inn realizes the scene in Old Martin's room as the publican of the Blue Dragon enters. Cagey and slightly paranoid Old Martin implies that the landlady, Mrs. Lupin, is an agent of one of the Chuzzlewit clan, all of whom are eager to learn just how ill he is, and whether he will change his will to include them. The next scene, Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's, continues this theme of watchful suspicion. Steig notes the symbolism inherent in Old Martin's physical separation from the kindly landlady of the Blue Dragon:

Several of the other plates in the first five parts comment by their subjects on young Martin's situation, and also are important iconographically. Thus, "Martin Chuzzlewit suspects the landlady without reason", centering upon young Martin's grandfather, parallels the first plate through the theme of exclusion, for old Martin suspects and excludes Mrs. Lupin, and his withdrawal from her and most of humanity is expressed graphically by the curtain which divides the plate in two. The parallel is to Pecksniff's exclusion of John Westlock, whose figure is partly visible in the first plate. Old Martin and his grandson, their egoisms and mutual attainment of self-knowledge, are also paralleled throughout the novel. [Steig, Chapter 3, p. 65]

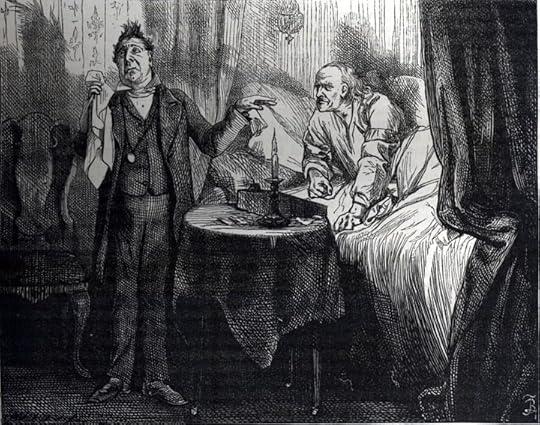

Old Martin and the Will

Chapter 3

Harry Furniss

The Charles Dickens Library Edition, Volume 7 (1910)

Commentary:

Here is a graphic representation of Old Martin's dilemma as he simply cannot determine which among his many predatory relatives is most deserving of inheriting his fortune. Old Martin here, however, bears little resemblance to the character drawn by Hablot Knight Browne in the 1843-44 serial and elaborated by seventies illustrator Fred Barnard in The Household Edition. The Furniss image, necessarily derivative, is rather more cartoon-like than Phiz's and certainly less realistic than Barnard's version of the canny senior. The writing table, pen, and ink that Old Martin has just been using to draw up yet another will are conspicuously positioned in the illustration, which is Furniss's re-drafting of a similar illustration in the original serial. One of the strongest and most upright of Dickens's characters in the novel, Old Martin, attended by Mary Graham and wearing a scull-cap, appears in a place of prominence in the ornamental border for Furniss's title-page.

Over the course of a number of illustrated editions of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) a number of images of the novel's suspicious and secretive rich man, pursued by avaricious relatives and their hangers-on, Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867 in the Diamond Edition), Fred Barnard (1872 in the transatlantic Household Edition), and Harry Furniss (1910). However, all of these are based on the original conception by Phiz, whose final illustration of him, as a stern Old Testament prophet, inspired by divine wrath, is perhaps the most compelling and dynamic. Despite the fact that the book bears his name and that his wealth is the mainspring of the action of the main plot, Old Martin is at best a minor character, rarely seen, so that, for example, American illustrator Felix Octavius Carr Darley elected not to depict him at all in the Sheldon and Company Household Edition volumes of 1863, and he was hardly worthy of visual comment by visual satirist Clayton J. Clarke (1910) in the Players' Cigarette Cards series. In the Household Edition (1872), the illustrator chose the arrival of the sanctimonious Pecksniff at the Blue Dragon as more worthy of visual comment in this same chapter.

In the background shadows stand Mary Graham (right) and Mrs. Lupin (left), but Furniss's twin focal points are the irascible old man's face and the destruction of the latest will in the candle flame, whereas Phiz's interest in January 1843 steel engraving Martin Chuzzlewit Suspects the Landlady Without Any Reason is evenly divided between the three figures because one of the functions of this early illustration is to introduce these characters to the reader. Although Martin has already destroyed his latest draft in the 1910 plate, in Phiz's he is still writing, so that Phiz has placed the candle and the quill at the centre of the composition, whereas Furniss emphasizes the smoke from the burning document as he shows the old man, fully reclining on the bed. Although both plates contain a side-table, only the 1910 plate has the chair, just vacated by Mary, the old man's confidant and nurse. One certainly receives a better sense, too, of Old Martin's room at the inn in the Phiz illustration, which presents the occupant as an individual rather than, as in Furniss's plate, a type.

Mr. Pecksniff, looking sweetly over the half-door of the bar, and into the vista of snug privacy beyond, murmured 'Good evening, Mrs. Lupin.' —

Chapter 3

Fred Barnard (1872), Household Edition

Commentary:

Whereas Phiz thirty years earlier had chosen Pecksniff and his daughters snugly and smugly ensconced in their parlour as his subject for Chapter 2, Barnard moves from his initial, uncaptioned plate depicting Pecksniff's having taken a tumble at the foot of his own steps in Chapter 2 (p. 1) to the snuggery of the village public house and its attractive proprietress. Mrs. Lupin has summoned Mr. Pecksniff to lend a professional opinion as to the state of health of the elderly gentleman just taken ill upon the road — in fact, none other than his wealthy relative, Martin Chuzzlewit, Senior. Since the letterpress has already introduced readers to both the figures in and the setting of this second illustration, Barnard could simply have provided a portrait of the cheery publican, the Widow Lupin, "broad, buxom, comfortable, and good looking" (Ch. 3) whose visage betokens "hearty participation in the good things of the larder and the cellar," but he has not. Ample-skirted and "comely" as in Dickens's description, Barnard's Mrs. Lupin is neither "dimpled" nor "plump," if we may judge by her profile. As in the novel, she is shown seated by her fireside in the little back parlour. Pecksniff has removed his hat, but has yet to enter and remove his gloves in order to warm his hands before the fire. Made apprehensive by the old gentleman's suspicious nature and pointed interrogation of her in the sick-chamber (the scene Phiz had chosen to depict) minutes earlier, Mrs. Lupin swings around in her chair as Pecksniff announces his benign and soothing presence in customary, oily manner. (A little more obsequiousness accompanied by writhing of the hands and we would have Uriah Heep foreshadowed.) Barnard has filled in the bulk of the parlour scene from his own imagination, providing such details as the mother cat and two kittens (right), Mrs. Lupin's stitchery on the candle-lit table (centre), and the open shelves on either side of her dutch door, none of which constitutes the sort of emblemmatic significance with which Phiz imbued his scenes. Pecksniff, his dress and figure providing visual continuity from the opening illustration, is upstage centre, ready to play the role of the amiable and concerned professional man bent on performing an altruistic act. This second plate, then, sets us up for the third in Barnard's sequence: the sanctimonious hypocrite and the irascible, suspicious patient.

"We will say, if you please," added Mr. Pecksniff, with great tenderness of manner

Chapter 3

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

The moment realized sets up readers' expectations as the illustrator reveals what will happen over the page. This scene in Old Martin's sick-chamber is comparable to Phiz's second plate for the first monthly number, "Martin Chuzzlewit suspects the landlady without any reason." The chamber's lone candle realistically casts the shadows of Barnard's figures on the wall-paper, and establishes continuity with the text (old Martin's burning of yet another will) and Phiz's plate. In fact, Barnard seems to be inviting comparison with Phiz here since he has selected a similar but not identical subject. In each illustrator's narrative-pictorial sequence these plates begin what Michael Steig has termed "old Martin's progress" (Dickens Studies Annual 2: 126).

In the original serial illustration by Dickens's official illustrator, Phiz (Hablot Knight Brown), a paranoid, aged miser complete with patriarchal skullcap (which Phiz possibly intended to evoke the Old Testament story of Isaac's choice of heirs, Esau and Jacob) is in self-isolation imposed by his wealth. As the head of a greedy clan, he has good reason to be suspicious. However, whereas in Phiz's plate Martin Chuzzlewit Suspects the Landlady Without Any Reason, in his paranoia the invalid has accused the kind-hearted publican without any justification, in Barnard's he exercises reasonable caution in suspecting the motives of the loquacious newcomer who proclaims himself in sermonical tones a purely disinterested "friend," but who in fact is a distant member of the Chuzzlewit clan.

The Chuzzlewit "curse" under which old Martin feels himself labouring implies a simple, superstitious nature in his interview with Mrs. Lupin she counsels is only the operation of "sick fancies." Several pages later, when we have learned how his fortune has brought nothing by familial dissention, his aggressive demeanour (as signalled by his clenched fist and jutting jaw) seems fully justified, especially since we have already judged Pecksniff a posturing, pompous hypocrite. In addition to maintaining continuity through old Martin's posture and attitude (despite the absence of the skullcap from the Phiz plate), Barnard has chosen to furnish the apartment exactly after Phiz's manner, with a small, round table at the bedside, the rumpled bedclothes, and the abundant draperies of the bed-curtains. However, whereas Phiz had employed the drapery to suggest the old man's closeness to Mary Graham and his tendency to exclude others from his confidence, in Barnard's plate the pillar of rectitude and platitudinous sentiment has replaced the curtains, which Barnard has re-positioned to the extreme right as a frame to complement the chair and Pecksniffian shadow at the extreme left. Whereas Phiz has drawn the viewer's eye right of centre, to the heads of old Martin and young Mary, in order to convey their sympathetic understanding, Barnard has shifted the mood from watchful suspicion to character comedy as Pecksniff performs his serio-comic monologue for an audience of one. As the left hand, gesturing, and the right hand, stagily displaying the oversized handkerchief, a theatrical property long before vaudeville, suggest, Pecksniff is always acting a part. He is as comic a tragedian as Wopsle will later prove to be whether in the Gargerys' parlour or on the London stage in Great Expectations (1861, not issued in the Household Edition until 1876, and illustrated not by Barnard, but by F. A. Fraser).

Curiously, the 1872 Household Edition volume, the second in the twenty-two volume series, has positioned this third Barnard plate prior to the moment realized by the second plate, leaving the reader to wonder when the text realized by the third plate will occur — a proleptic reading.

The Mistress of The Blue Dragon

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Commentary:

In this third full-page character study for the novel, Eytinge characterises Mark Tapley's employer, Mrs. Lupin, as a young and attractive widow and self-assured businesswoman. Victorian Web in a print one.

Despite the fact that the artist has placed her in the context of the travellers' room rather than in Old Martin's sick-room sitting beside Mary Graham, the old man's attendant, we should connect this passage to the publican's portrait:

The mistress of the Blue Dragon was in outward appearance just what a landlady should be, — broad, buxom, comfortable, and good looking, with a face of clear red and white, which, by its jovial aspect, at once bore testimony to her hearty participation in the good things of the larder and cellar, and to their thriving and healthful influences. She was a widow, but years ago had passed through her state of weeds, and burst into flower again; and in full bloom she had continued ever since; and in full bloom she was now; with roses on her ample skirts, and roses on her bodice, roses in her cap, roses in her cheeks, — aye, and roses, worth the gathering too, on her lips, for that matter. She had still a bright black eye, and jet black hair; was comely, dimpled, plump, and tight as a gooseberry; and though she was not exactly what the world calls young, you may make an affidavit, on trust, before any mayor or magistrate in Christendom, that there are a great many young ladies in the world (blessings on them one and all!) whom you wouldn’t like half as well, or admire half as much, as the beaming hostess of the Blue Dragon.

As this fair matron sat beside the fire, she glanced occasionally with all the pride of ownership, about the room; which was a large apartment, such as one may see in country places, with a low roof and a sunken flooring, all downhill from the door, and a descent of two steps on the inside so exquisitely unexpected, that strangers, despite the most elaborate cautioning, usually dived in head first, as into a plunging–bath. [Chapter 3; Diamond Edition]

Shortly after this point, Old Martin accuses the kindly landlady of The Blue Dragon in Phiz's dramatic introduction of Mrs. Lupin, "Martin Chuzzlewit Suspects The Landlady Without Any Reason", of being in league with one of his many mercenary relatives. Eytinge's free handling of his subject, although far less dramatic, has the advantage of presenting a study of Mrs. Lupin as a specimen of mature, feminine beauty and self-assurance (as signified by her direct gaze, erect posture, and hand on her hip), highlighting those qualities that make her so attractive. Thus, she in her person, intellect, personality, and considerable property — the well-stocked public house suggested by the bottles that surround her in Eytinge's woodcut — offers a powerful inducement not to leave this very comfortable situation which has failed to test his mettle.

Kim wrote: "Hall was a genuine comedy figure. Such oily and voluble sanctimoniousness needed no modification to be fitted to appear before the footlights in satirical drama. He might be called an ingenuous hypocrite, an artless humbug, a veracious liar, so obviously were the traits indicated innate and organic in him rather than acquired. Dickens, after all, missed some of the finer shades of the character; there can be little doubt that Hall was in his own private contemplation as shining an object of moral perfection as he portrayed himself before others. His perversity was of the spirit, not of the letter, and thus escaped his own recognition. His indecency and falsehood were in his soul, but not in his consciousness; so that he paraded them at the very moment that he was claiming for himself all that was their opposite."

I think this may also be true of Pecksniff, who even keeps up the facade of sanctity and moral perfection in his very family circle. The question is whether he really believes in his spiel, or whether unctious hypocrisy has grown on him so much that, like many a bad habit, it is difficult for him to do without it. Maybe, in the course of the novel we will learn more about that question.

Thanks a lot for this information, Kim! So not only Skimpole and Uriah Heep and Podsnap were based on people Dickens knew, but also the venerable Mr. Pecksniff. It is to be argued, however, whether the people concerned recognized themselves in their respective literary portraits, and whether they felt flattered at being immortalized by Dickens. Probably, they didn't so much.

I think this may also be true of Pecksniff, who even keeps up the facade of sanctity and moral perfection in his very family circle. The question is whether he really believes in his spiel, or whether unctious hypocrisy has grown on him so much that, like many a bad habit, it is difficult for him to do without it. Maybe, in the course of the novel we will learn more about that question.

Thanks a lot for this information, Kim! So not only Skimpole and Uriah Heep and Podsnap were based on people Dickens knew, but also the venerable Mr. Pecksniff. It is to be argued, however, whether the people concerned recognized themselves in their respective literary portraits, and whether they felt flattered at being immortalized by Dickens. Probably, they didn't so much.

Samuel Carter Hall (9 May 1800 – 11 March 1889) was an Irish-born Victorian journalist who is best known for his editorship of The Art Journal and for his much-satirised personality. Hall was born at the Geneva Barracks in Waterford, Ireland. His London-born father was Robert Hall, an army officer and, while in Ireland, engaged in working copper mines which ruined him. His mother supported the family of 12 children with her own business in Cork. He married Ann Kent at Topsham, 6 April 1790. Ann Hall supported the family, including 12 children, by running a business in Cork, Ireland. Hall was the fourth son.

In 1821, he left Ireland and went to London. He entered law studies at the Inner Temple in 1824, but never practised, though he was finally called to the bar in 1841. Instead, he became a reporter and editor.

In 1839, Hodgson & Graves, print publishers, employed Hall to edit their new publication, Art Union Monthly Journal. Not long after, Hall purchased a chief share of the periodical. By 1843, he started giving an expensive, unprofitable novelty, sculpture engravings. In 1848, with Hall still unable to turn a profit, the London publisher George Virtue purchased into the Art Union Monthly Journal, retaining Hall as editor. Virtue renamed the periodical The Art Journal in 1849.

In 1851, Hall engraved 150 pictures from the private collection of the Queen and Prince Albert, and the engravings were featured in the journal's Great Exhibition edition. Though this edition was quite popular, the journal remained unprofitable, forcing Hall to sell his share of The Art Journal to Virtue, but staying on as editor.

As editor, Hall exposed the profits that custom-houses were earning by importing Old Masters, and showed how paintings are manufactured in England. While The Art Journal became notable for its honest portrayal of fine arts, the consequence of Hall's actions was the almost unsaleability of old masters such as a Raphael or a Titian. His intention was to support modern British art by promoting young artists and attacking the market for unreliable old masters. The early issues of the Journal strongly supported the artists of The Clique and attacked the Pre-Raphaelites. Hall remained deeply unsympathetic to Pre-Raphaeliism, publishing several attacks upon the movement. Hall resigned the editorship in 1880, and was granted a Civil List pension for his long and valuable services to literature and art.

His wife, Anna Maria Fielding (1800–1881), became well known (publishing as "Mrs S.C. Hall"), for her numerous articles, novels, sketches of Irish life, and plays. Two of the last, The Groves of Blarney and The French Refugee, were produced in London with success. She also wrote a number of children's books, and was practically interested in various London charities, several of which she helped to found.

Hall rose to prominence as the editor of the Art Journal and his wife Anna Maria was a popular novelist. Together they compiled A book of Memories of Great Men and Women of the Age from Personal Acquaintance (1871), described as a 'series of written portraits'. The couple's other project, putting up commemorative plaques on houses (before the official blue plaque scheme was initiated in 1867), reflects a more general growth in interest in personal history during the period.

Hall's notoriously sanctimonious personality was often satirised, and he is regularly cited as the model for the character of Pecksniff in Charles Dickens's novel Martin Chuzzlewit. As Julian Hawthorne wrote,

Hall was a genuine comedy figure. Such oily and voluble sanctimoniousness needed no modification to be fitted to appear before the footlights in satirical drama. He might be called an ingenuous hypocrite, an artless humbug, a veracious liar, so obviously were the traits indicated innate and organic in him rather than acquired. Dickens, after all, missed some of the finer shades of the character; there can be little doubt that Hall was in his own private contemplation as shining an object of moral perfection as he portrayed himself before others. His perversity was of the spirit, not of the letter, and thus escaped his own recognition. His indecency and falsehood were in his soul, but not in his consciousness; so that he paraded them at the very moment that he was claiming for himself all that was their opposite.

Hall was a convinced spiritualist. He was the chairman for the British National Association of Spiritualists, in 1874.

Does he look like Pecksniff?