The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

Dombey, Chapters 14 - 16

These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly).

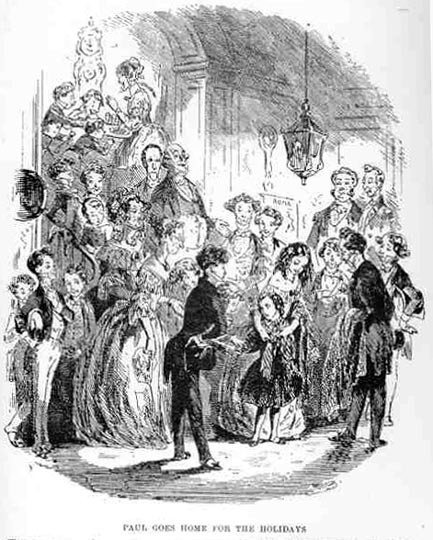

These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly). The party was particularly sad, with everyone but Paul in the know and doing their best to show him a happy, joyous time.

The role played by Dombey was strange and interesting. He's sad beyond belief and filled with grief, yet he's a shadow to his son; hardly seen and quickly slipping away when he is. Even in death, Dombey is distant. In many ways, my heart goes out to him.

But more, it goes out to Florence. Throughout, she is brave and shows only a happy face to her brother. Not once does she falter and show him any sadness or pain; yet she's filled with it.

I don't know what else to say. These chapters filled me with sadness (as Dickens intended, I'm sure).

(why is Paul wearing a dress in that picture? I went back and it appears that he's also wearing one in the drawing of him sitting beside Mrs. Pipchin by the fire. Was that normal boy's wear in Dickens' times? The other boys in the picture are wearing pants. Why not Paul?)

Paul. My favorite little Paul is gone. :( Even though I knew it was coming (from reading the footnote to the preface - argh!), it was very sad indeed. Petra, you're right that the foreshadowing was not subtle at all. Even if I didn't know for sure what was coming, I sure would have gotten the hint beforehand.

Paul. My favorite little Paul is gone. :( Even though I knew it was coming (from reading the footnote to the preface - argh!), it was very sad indeed. Petra, you're right that the foreshadowing was not subtle at all. Even if I didn't know for sure what was coming, I sure would have gotten the hint beforehand.I found Dombey's role very sad also. There was a part where Paul comes home and his father is there and Paul seems not to even recognize him. I wondered if it was because he had not seen him in awhile, coupled with Dombey not visiting Paul very often in the first place. Or if Paul was in a sort of feverish delirium at the time.

I also thought that Paul was wearing a dress in that picture. But then I thought that since he was getting ready to head home, that what I thought was a dress was actually his overcoat? I guess I'm still not sure.

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly).

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly). The par..."

Hi Petra

Kids at that age, no matter what sex, wore nighties or night gowns, so I guess that's what he's wearing, being in bed or next to the fire (presumably before bedtime).

Kim wrote: "

Kim wrote: "Profound Cogitation of Captain Cuttle

Chapter 15"

Thanks for the picture Kim. Sadly, for this read, I do not have an edition with these wonderful pictures in it.

Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has she got now? Hopefully she will carry on with her studies to keep her focused.

Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has she got now? Hopefully she will carry on with her studies to keep her focused.I also agree that the foreshadowing is very strong here.

I found it interesting that the whole of chapter 14 was told in third person limited (from the perspective of Paul, obviously) as I really did feel as though I was seeing it through the eyes of a young naive boy who didn't know his fate, whilst, as a mature reader, you could sense that something was going on, judging from the behaviour of the other characters. Paul's interpretation of it all was sad but also heartwarming. In a funny way, it softens the blow of the harsh reality, knowing that he saw his destiny as something more mystical that he could really explain. He just felt that he was going somewhere and felt at peace with the water. Early at Blimber's the waves used to annoy him, then they began to soothe him. It seems that at that point, it became the beginning of the end.

I wonder if the water becomes a motif, just as the railway, like Tristram points out, becomes a motif for change?

Joy wrote: "Dickens is always killing off little kids. It's what he does. Poor little guy."

Joy wrote: "Dickens is always killing off little kids. It's what he does. Poor little guy."It seems very hard of him to do so, Joy, but maybe for 19th century readers these deaths were less extraordinary because of the higher infant mortality.

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly).

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly). The par..."

The foreshadowing passages were so numerous that it was hard to ignore them, and once again I thought that Dickens did not trust his audience too much with respect to subtlety.

I find brilliant, however, Dickens's way of treating Dombey's presence at Paul's bed. His being a shadow, hardly recognized by Paul and even apt to fill him with fear, shows what kind of remote father he was. Paul's repeated entreaties to tell Mr. Dombey that he was already better and that he, i.e. Dombey, should not cry, are also very touching, and yet they seem to indicate that Paul feels he is under some sort of obligation towards his father.

It is to be seen in what spirit Mr. Dombey will react to Paul's request to remember Walter, whom he was so fond of. I mean it might have been galling to Mr. Dombey not to be recognized by his own son, while Paul made a point of having all those people around him in his last few days whom Mr. Dombey regarded as socially inferior - such as Walter and Polly. And then what will Mr. Dombey think about Paul's last words,

"'Mama is like you, Floy. I know her by the face! [...]'" ? Surely, he will not be very glad.

Kate wrote: "Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has she got now?..."

Kate wrote: "Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has she got now?..."I agree with you, Kate, that the third person limited view made Chapters 14 and 16 very heartwarming, and you can see that even the Blimbers are very kind people - and, perhaps, more surprisingly, Mrs. Pipchin has for once stopped thinking about herself only.

I would tend to regard the river and the sea, the continuing to and fro of the waves, as a symbol of death, especially when Paul feels threatened by the sound of the Thames and tries to fend off the everlasting tide of the river in his fever dreams. Seeing the waves as a symbol of death may, of course, imply some evil foreboding with regard to what is going to become of Walter Gay, who is going on a voyage, after all.

Tristram wrote: "Kate wrote: "Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has..."

Tristram wrote: "Kate wrote: "Like everyone else, I found this very sad. Poor Paul, but now I really feel for Florence. With Paul gone and everyone else she ever got close to having been banished already, who has..."Tristram and Kate

I'll toss my hat into the ring agree with you both. The use of waves, water and the sea forms a very strong symbol for both Paul's coming death and the possibility of some disaster or trauma when Walter sails for The Barbados. Dickens is also able to soften any of the schools' sharp edges and bring joy and celebration as a counterbalance for Paul's weakening condition in this chapter. We see Paul's concern with time as bells are heard. I think it was in TOCS, but I know it was Kim who did some wonderful research on what bells meant in terms of their ringing and their connection to death.

Chapter 14 gives us, once again, Dickens's concentration on Florence and how both accomplished and admired she is. Then there is Diogenes, a wayward dog that Paul befriends. It is so sad that while Paul finds yet another focus for his innocent love the reader feels the coming end to his story.

Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walter. Walter wants to "preserve her image in his mind as something precious, unattainable ..."

Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walter. Walter wants to "preserve her image in his mind as something precious, unattainable ..."I think a key focus of this chapter is what doesn't exist anymore, and that is Stagg's Gardens. As Kate mentioned in post 8 the railway is a major change. "The was no such place as Stagg's Gardens. It had vanished from the earth." The old world of "waste ground" and "refuse matter" was now filled with warehouses and passengers. Change. Modernization. The replacement of the old fashioned with the new. I believe Dickens is signaling not only a specific change as brought on by the railroad but expanding his vision to sweep all of Victorian society. Paul is constantly referred to as old-fashioned. As good and kind and gentle as he might be he is not part of the relentless march forward of progress, whether that progress be perceived as good or bad.

When I read this chapter I was impressed with how Dickens infused it with such energy and momentum. Walter's encounter with Susan Nipper in a coach looking for Stagg's Gardens is very powerful. Susan Nipper is searching for a place that no longer exists and thus the person who used to live there has also moved on. When found, Mrs. Richards returns to Dombey's house with Walter to find a place of shadows and mourning, a place waiting for death. The London scene of energy, growth and change contrasts strongly to the tomb-like anticipation of death found at Dombey's home serves to heighten the contrast of each other's presence.

Well, Dickens is certainly the master of writing death scenes. The passing of Paul Dombey is powerful and memorable. The energy and forward momentum that was generated in ch.15 is perfectly counterbalanced here with the somber, mournful reality of an innocent child's death.

Well, Dickens is certainly the master of writing death scenes. The passing of Paul Dombey is powerful and memorable. The energy and forward momentum that was generated in ch.15 is perfectly counterbalanced here with the somber, mournful reality of an innocent child's death. Dickens may not be the most subtle of authors when using foreshadowing so I sure the serial readers of his time (and us as we move through the book) have two possible plotlines to anticipate. Paul asks his father to "Remember Walter" and Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all."

There is so much to anticipate!

A thought on Paul's clothes in the picture that Kim gave us. It was not uncommon for young male children of the nobility and aristocracy to wear a dress especially during family portraits and formal occasions. Many portraits of established families show young male children dressed as such. Such attire was certainly not worn by the lower classes who would only own and thus have "work" clothes.

A thought on Paul's clothes in the picture that Kim gave us. It was not uncommon for young male children of the nobility and aristocracy to wear a dress especially during family portraits and formal occasions. Many portraits of established families show young male children dressed as such. Such attire was certainly not worn by the lower classes who would only own and thus have "work" clothes. My guess is that this engraving was meant to suggest two ideas. The first is that Paul is the child of a wealthy family. The second, and more telling, is that this form of young male child attire was rapidly falling out of fashion by the mid-Victorian age. Such dress is most commonly seen in the aristocratic families of the 17C and 18C. Thus, the constant references to Paul as being "old-fashioned" is further confirmed by his clothing. I realize Dombey is neither titled nor an aristocrat but he is presented as being wealthy, respected and from a lineage of important Dombeys.

Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""

Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""The footnote in my book says this last paragraph was omitted from 1958 and on, since readers said it was anticlimactic. I smiled with approval after reading that, because I had thought the same thing. I wished the chapter had finished with Paul's death and not Miss Tox's thoughts on what "Dombey and Son" actually now meant. I think the readers are keen enough to have figured that out without having had been told so by Miss Tox.

Peter wrote: "A My guess is that this engraving was meant to suggest two ideas.... The second, and more telling, is that this form of young male child attire was rapidly falling out of fashion by the mid-Victorian age. Such dress is most commonly seen in the aristocratic families of the 17C and 18C. Thus, the constant references to Paul as being "old-fashioned" is further confirmed by his clothing."

Peter wrote: "A My guess is that this engraving was meant to suggest two ideas.... The second, and more telling, is that this form of young male child attire was rapidly falling out of fashion by the mid-Victorian age. Such dress is most commonly seen in the aristocratic families of the 17C and 18C. Thus, the constant references to Paul as being "old-fashioned" is further confirmed by his clothing."Interesting interpretation here, Peter, I like it. Not knowing what was in fashion during this time period, I would not have picked up on this.

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""The footnote in my book says this last paragraph was omitted from 1958 and on, since readers said it was ..."

I agree. The chapter should have ended with the death of Paul. This is another example of how attuned Dickens was to his readers. I guess Dickens thought his original ending of Ch 16 would be a boost in reader anticipation.

As for the speculation on Paul's clothing in the picture, I am not expert, or even amateur in the history of clothing but did take a course long ago and I remember seeing pics of young (2...5) wearing dresses. Paul is a bit older than that but it may be a reasonable explanation. Perhaps someone else will help out.

I had not expected Paul's death. I knew that he was very weak and ill, so perhaps I was in denial. So very sad.

I had not expected Paul's death. I knew that he was very weak and ill, so perhaps I was in denial. So very sad.

Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walter. Walter wan..."

Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walter. Walter wan..."Peter,

I heartily agree with you, and I want to add that apparently for all the change in Stagg's Garden there is some sort of continuity in that the people seem to be the same. Not only does Susan eventually find the Toodles, but also the chimney-sweep has remained in that place. In other words, Stagg's Garden is full of people who have managed to keep up with the changing times.

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""

Linda wrote: "Peter wrote: "Miss Tox comments "To think Dombey and son should be a Daughter after all.""The footnote in my book says this last paragraph was omitted from 1958 and on, since readers said it was ..."

Yes, Linda, I, too, think that the statement by Miss Tox is anticlimactic, all the more so as Miss Tox is clearly a comic relief character and as such a little out of place in this context.

Nevertheless, Paul's dying scene was extremely affecting, and when I was reading it in bed my wife was bemused at seeing me with welled-up eyes over a book.

Nevertheless, Paul's dying scene was extremely affecting, and when I was reading it in bed my wife was bemused at seeing me with welled-up eyes over a book.She made no funny remark, which was all the nicer as some months ago I walked into the room when she was watching the tear-jerker The Hours, and on finding her crying I just asked, "Is the film that bad?"

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walte..."

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walte..."Yes. Changing times. Time. I think it will be, and already is, a major motif in the novel.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walte..."

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Walter Gay's energy and good nature are further developed in Ch 15 and Dickens makes sure that his readers know something is brewing in his creative mind to do with Florence and Walte..."I agree but I also see it as those people still being stuck in the same jobs so there is little improvement for them - the real change comes with those at the upper end of society.

Following on from my last comment (message 26), the idea of time seems to reflect in the waves for me. Waves continually come and go but life never changes. Perhaps Dickens meant to show this as a sign with them all (particularly Paul at this stage), that regardless of outside influences, life has its foretold path. In other words, the waves show that Paul cannot escape his fate.

Following on from my last comment (message 26), the idea of time seems to reflect in the waves for me. Waves continually come and go but life never changes. Perhaps Dickens meant to show this as a sign with them all (particularly Paul at this stage), that regardless of outside influences, life has its foretold path. In other words, the waves show that Paul cannot escape his fate.

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly).

Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wrongly). The par..."

So many points in that post that I agree with. I think it was inevitable from the beginning that Paul would die -- he was never a strong child. Sorrow for both Dombey and Florence, definitely.

What will Dombey do now. Will he turn to Florence, who is by now, what, 15 or 16 and become, as miss Tox suggests, Dombey and daughter? (Was that even possible in the mid-1800s?) Will he wait for Florence to marry and hope she marries a man who can join the firm? Will he marry again and try to produce an heir who will survive to become Son? So many options before Dickens to choose from!!

Tristram wrote: "Joy wrote: "Dickens is always killing off little kids. It's what he does. Poor little guy."

Tristram wrote: "Joy wrote: "Dickens is always killing off little kids. It's what he does. Poor little guy."It seems very hard of him to do so, Joy, but maybe for 19th century readers these deaths were less extra..."

It also gives some powerful emotional impact to the book, more so than killing off adults would.

Tristram wrote: "I find brilliant, however, Dickens's way of treating Dombey's presence at Paul's bed. His being a shadow, hardly recognized by Paul and even apt to fill him with fear, shows what kind of remote father he was."

Tristram wrote: "I find brilliant, however, Dickens's way of treating Dombey's presence at Paul's bed. His being a shadow, hardly recognized by Paul and even apt to fill him with fear, shows what kind of remote father he was."True. But at least he was trying to be present in the best way he knew how. When his wife died, if I recall correctly, he didn't even bother trying to visit her, did he?

Linda wrote: "I wished the chapter had finished with Paul's death and not Miss Tox's thoughts on what "Dombey and Son" actually now meant. I think the readers are keen enough to have figured that out without having had been told so by Miss Tox. "

Linda wrote: "I wished the chapter had finished with Paul's death and not Miss Tox's thoughts on what "Dombey and Son" actually now meant. I think the readers are keen enough to have figured that out without having had been told so by Miss Tox. "But is that comment more foreshadowing, that Miss Tox will eventually marry Dombey and produce the son that he so desperately needs (and further push Florence aside)? There is so much foreshadowing in the book that I can't shake off the feeling that this may be yet more.

Everyman wrote: "But is that comment more foreshadowing, that Miss Tox will eventually marry Dombey and produce the son that he so desperately needs (and further push Florence aside)?"

Everyman wrote: "But is that comment more foreshadowing, that Miss Tox will eventually marry Dombey and produce the son that he so desperately needs (and further push Florence aside)?"I had not thought of that possibility. Dombey must be about 53 or 54 years old now? Was that too old to consider remarrying and having another child for the time? After seeing him waiting and waiting for little Paul to "hurry and grow up" so he could have his son, I wonder if the thought of trying for another son seems far fetched at the moment, having to go through all that waiting again.

Linda wrote: "I had not thought of that possibility. Dombey must be about 53 or 54 years old now? Was that too old to consider remarrying and having another child for the time?."

Linda wrote: "I had not thought of that possibility. Dombey must be about 53 or 54 years old now? Was that too old to consider remarrying and having another child for the time?."I think lots of men that age remarried. Deaths in childbirth were not rare, so men of sufficient wealth tended to have several wives (sequentially). It was a few years earlier, but Henry VIII was 52 when he married his sixth wife, Catherine Parr.

Kate wrote: "Following on from my last comment (message 26), the idea of time seems to reflect in the waves for me. Waves continually come and go but life never changes. Perhaps Dickens meant to show this as a ..."

Kate wrote: "Following on from my last comment (message 26), the idea of time seems to reflect in the waves for me. Waves continually come and go but life never changes. Perhaps Dickens meant to show this as a ..."... and maybe that an individual person's plans and intentions are like someone sitting in a small boat in the middle of the ocean ... i.e. nearly meaningless.

Everyman wrote: "Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wron..."

Everyman wrote: "Petra wrote: "These chapters were so sad. The foreshadowing isn't subtle but even then I at first thought I was reading wrong into the words (and hoping so that I was right about being reading wron..."I think it was possible for a woman to own and conduct a business even in 19th century England. Provided that she was unmarried or widowed for in the case of matrimony her property would by law have gone into the hand of her husband.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I find brilliant, however, Dickens's way of treating Dombey's presence at Paul's bed. His being a shadow, hardly recognized by Paul and even apt to fill him with fear, shows what k..."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I find brilliant, however, Dickens's way of treating Dombey's presence at Paul's bed. His being a shadow, hardly recognized by Paul and even apt to fill him with fear, shows what k..."He didn't because he was too concerned with his new-born son.

Hilary wrote: "Naughty Tristram!!! You must have a saintly wife! [g]"

Hilary wrote: "Naughty Tristram!!! You must have a saintly wife! [g]"I can think of two people on here who must have wives who are saintly. Counting me that's three. :-}

This is what I can find about what Paul may be wearing:

This is what I can find about what Paul may be wearing:From the mid-16th century until the late 19th or early 20th century, young boys in the Western world were unbreeched and wore gowns or dresses until an age that varied between two and eight. The boys wore dresses much like those worn by their sisters. These dresses in the mid-1800s could be quite elaborate. Thousands of photographs from the mid- and late-19th century show boys wearing dresses. This was not an exclusively Victorian custom, rather, boys in European cultures wore dresses for centuries and it continued to the turn-of-the 20th century. As boys grew older some differentiation might be made such as less lace and frilly aplique. Boys outfitted in frocks during the early part of 19th Century often wore knee-length or below the knee pantaletts, often trimed in frilly lace. Other frocks might have embroidered, somewhat less femine pantaloons. Other outfits for somewhat older boys were frock-like tunics. Scholars looking at drawings and paintings from the era frequently have trouble differentiating girls from boys. We only see the popularity of this fashion waning after about 1895 and by about 1905 it was no longer a major fashion convention. It did not entirely disappear and we continue to see a few boys in dresses until after World War I. After the War, however, it became the exception rather than the rule. Only infants wore dresses.

Charles Dickens was reportedly influenced by a portrait as to how he portrayed the boy character Little Paul in his novel Dombey and Son. The portrait was "Painting of a Boy" by W.J. Orchardson RA. The portrait is of a boy named W.H. Keith. He was the son of James Keith who was an Edinburgh printseller.

Kim wrote: "Charles Dickens was reportedly influenced by a portrait as to how he portrayed the boy character Little Paul in his novel Dombey and Son."

Kim wrote: "Charles Dickens was reportedly influenced by a portrait as to how he portrayed the boy character Little Paul in his novel Dombey and Son."Wow. He totally looks like little Paul - and he appears deep in contemplation too.

Thanks for the info on the dressing habits too, Kim

Peter wrote: "We see Paul's concern with time as bells are heard. I think it was in TOCS, but I know it was Kim who did some wonderful research on what bells meant in terms of their ringing and their connection to death."

Peter wrote: "We see Paul's concern with time as bells are heard. I think it was in TOCS, but I know it was Kim who did some wonderful research on what bells meant in terms of their ringing and their connection to death."This is in Chapter 14:

"The ice being thus broken, Paul asked him a multitude of questions about chimes and clocks: as, whether people watched up in the lonely church steeples by night to make them strike, and how the bells were rung when people died, and whether those were different bells from wedding bells, or only sounded dismal in the fancies of the living. Finding that his new acquaintance was not very well informed on the subject of the Curfew Bell of ancient days...

Here's what I found about the bells:

"Church bells are rung in three basic ways: normal (peal) ringing, chiming, or tolling. Normal ringing refers to the ringing of a bell or bells at a rate of about one ring per second or more, often in pairs reflecting the traditional "ding-dong" sound of a bell which is rotated back and forth, ringing once in each direction. "Chiming" a bell refers to a single ring, used to mark the naming of a person when they are baptized, confirmed, or at other times. Many Lutheran churches chime the bell three times as the congregation recites the Lord's Prayer: once at the beginning, once near the middle, and once at the "Amen"."

First there is the dead bell. "Belief in the supernatural was common in the Middle Ages and special protective powers were sometimes attributed to certain objects, including bells. The Church itself condoned the use of bells to frighten away evil spirits and this ensured the practice's survival and development. Bells were often baptised, and once baptised were believed by many to possess the power to ward off evil spells and spirits. The use of the dead bell was typical of this belief, rung for the recently deceased to keep evil spirits away from the body.

The dead bell was therefore originally rung for two reasons: firstly to seek the prayers of Christians for a dead person's soul, and secondly to drive away the evil spirits who stood at the foot of the dead person's bed and around the house.

"Originally a Dead bell was a form of hand bell used in Scotland and northern England in conjunction with deaths and funerals up until the 19th century.

Then there is a death knell. "Originally a death knell would be rung at the actual time of death.

The ancient custom fell into disuse in England by the end of the 18th century. More customary at the end of the 19th century was to ring the Death Knell as soon as notice reached the clerk of the church or sexton, unless the sun had set, in which case it was rung at an early hour the following morning.

It was usual to repeat the knell early on the morning of the day when the funeral took place; but although canon law permitted tolling after the funeral there does not seem to be any record that this was practiced.

The manner of ringing the knell varied in different parishes. Occasionally the age of the departed was signified by the number of chimes (or strokes) of the bell, but the use of "tellers" to denote the sex was almost universal, and by far the greater number of churches in the counties of Kent and Surrey used the customary number of tellers, viz., three times three strokes for a man and three times two for a woman, with a varying use for children across the counties."

We also have a funeral bell. "Church bells are sometimes rung slowly (tolled) when a person dies or at funeral services.

"Tolling" a bell refers to the slow ringing of a bell, about once every four to ten seconds. It is this type of ringing that is most often associated with a death, the slow pace broadcasting a feeling of sadness as opposed to the jubilance and liveliness of quicker ringing.

Customs vary regarding when and for how long the bell tolls at a funeral. One custom observed in some liturgical churches is to toll the bell once for each year of the life of the deceased. Another way to tell the age of the deceased is by tolling the bell in a pattern. For example if the deceased was 75 years old, the bell is tolled seven times for seventy, and then after a pause it is tolled five more times to show the five."

And finally, what Paul mentions in the chapter is the "Curfew Bell".

"The curfew bell was a bell rung in the evening in Medieval England as the signal for everyone to go to bed.

A bell was rung usually around eight o'clock in the evening which meant for them to cover their fires - deaden or cover up, not necessarily put out altogether. The usual procedure was at the sound of the curfew bell the burning logs were removed from the centre of the hearth of a warming fire and the hot ashes swept to the back and sides. The cold ashes were then raked back over the fire so as to cover it. The ashes would then keep smoldering giving warmth without a live fire going. The fire could easily be reignited the next morning by merely adding logs back on and allowing air to vent through the ashes. A benefit of covering up the fire in the evening was the prevention of destructive conflagrations caused by unattended live fires, a major concern since at the time most structures were made of wood and burned easily.

In Medieval times the ringing of the curfew bell was of such importance that land was occasionally paid for the service. There are even recorded instances where the sound of the curfew bell sometimes saved the lives of lost travellers by safely guiding them back to town. A century later in England the curfew bell was associated more with a time of night rather than an enforced curfew law. The curfew bell was in later centuries rung but just associated with a tradition.The time of the curfew bell changed in later centuries after the Middle Ages to nine in the evening and sometimes even to ten. To this day in many towns there is a "curfew" at nine or ten that can be heard throughout the town, which is usually the town's emergency siren - sometimes used as the town's noon whistle."

Well that was all depressing. Except for the curfew bell that is. We have that by the way, if it is an emergency whistle. Ours "rings" at noon and 6:00 pm. So do the church bells.

A brief comment on Paul's vision of waves. When I was young I had a serious illness with high fever. One of the things about it was that the room seemed to move in and out in waves. While Paul's illness isn't specified in the text, I suspect, from my experience, that he had a high fever, maybe with other issues.

A brief comment on Paul's vision of waves. When I was young I had a serious illness with high fever. One of the things about it was that the room seemed to move in and out in waves. While Paul's illness isn't specified in the text, I suspect, from my experience, that he had a high fever, maybe with other issues.

Everyman wrote: "A brief comment on Paul's vision of waves. When I was young I had a serious illness with high fever. One of the things about it was that the room seemed to move in and out in waves. While Paul's ..."

Everyman wrote: "A brief comment on Paul's vision of waves. When I was young I had a serious illness with high fever. One of the things about it was that the room seemed to move in and out in waves. While Paul's ..."Interesting. It seems like a logical explanation.

Hi Lindsay, when I was reading it I got the image of a shark in my mind. I'm sure that there are many other interpretations. It felt to me as though Dickens was using this description to suggest that he was someone not to be trusted.

Hi Lindsay, when I was reading it I got the image of a shark in my mind. I'm sure that there are many other interpretations. It felt to me as though Dickens was using this description to suggest that he was someone not to be trusted.

Hilary wrote: "Hi Lindsay, when I was reading it I got the image of a shark in my mind. I'm sure that there are many other interpretations. It felt to me as though Dickens was using this description to suggest that he was someone not to be trusted..."

Hilary wrote: "Hi Lindsay, when I was reading it I got the image of a shark in my mind. I'm sure that there are many other interpretations. It felt to me as though Dickens was using this description to suggest that he was someone not to be trusted..."I got the same feeling. I couldn't help my mind straying to "the better to eat you with, my dear."

I read it as an indication of high insincerity. OTOH, I'm not sure Dickens meant it that way because in all other respects, Carker actually seems a quite decent and responsible chap. So I'm not really sure what Dickens was up to. But I am sure that any film version of D&S will need to cast a large set of pearly whites.

Hi Lindsay

Hi LindsayI agree with Hilary. Big teeth on a person who at first impression makes me uneasy is not a good sign.

Books mentioned in this topic

The Eustace Diamonds (other topics)The Eustace Diamonds (other topics)

Berenice (other topics)

what a sad reading this was, and this time Dickens really managed a more heartrending deathbed scene than in TOCS, probably also because unlike Little Nell - sorry, Kim, but truth will out - little Paul was a more lifelike creation who actually behaved the way a child might behave.

In Chapter 14 we already get a lot of foreshadowing with regard to what will finally happen in Chapter 16, such as the strange assessment of adult people who say that Paul is "old-fashioned". What they regard as old-fahsioned is probably just the child's inclination to deep thought, and seriousness, which we often find in children with serious health problems. However, Chapter 14, with its excursions into gentle humour, as when the quadrille at Dr. Blimber's takes place, is also strangely serene. Everybody behaves kindly to Paul, even Mrs. Pipchin does in her rough way.

In Chapter 15 then the scene changes to Walter, who asks the help of Captain Cuttle in breaking the bad news of Walter's going away to his uncle. Nevertheless, Captain is convinced that he can render Walter even better service, and thus he seems to seek an interview with Mr. Dombey at a most awkward moment. Maybe we'll get to know more of that later. Walter helps Susan find Polly - the whole neighbourhood has changed due to the railway, which again brings change in as a major motif of the novel - so that his old nurse can be with Paul during his last days on earth.

Chapter 15 also offers a candidate for characters with the funniest names - the Reverend Melchisedech Howler, nomen est omen.

Chapter 16 then describes how little Paul finally dies, and it is very interesting to consider the way the narrator deals with Mr. Dombey here.

I hope that notwithstandig the melancholy final note of this week's read, we are going to have a lively discussion.