The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

Dombey, Chapters 8 - 10

I believe it states that young Paul is 5 years old when he goes to Brighton, so that would make Florence around 11 years. And yes, I guess this means that the Major can hold a grudge against Miss Tox's snub after so many years past.

I believe it states that young Paul is 5 years old when he goes to Brighton, so that would make Florence around 11 years. And yes, I guess this means that the Major can hold a grudge against Miss Tox's snub after so many years past.Some of my favorite passages and descriptions occurred in chapter 8, especially descriptions of Mrs. Pipchin and young Paul. I will record them later when I have the copy of my book handy.

The passage where Mr. Dombey "teaches" young master Paul the value of money and how it corresponds to power was horrid, and then to see young Paul walking around upright afterward as if to show off his power was quite disheartening to see in such a young child.

I was also saddened to read of Walter's inner feelings concerning Florence after the meeting with Mr. Dombey and having Mr. Dombey get Uncle Sol out of his immediate financial troubles. Walter clearly had feelings for Florence, although he may not have been able to pinpoint those exact feelings, as he felt delighted upon seeing her here and there. He clearly felt deflated after his meeting with Mr. Dombey and having young Master Paul help his family out of trouble. It is this incident that demonstrates to Walter the clear difference between families with money and power, and families without. And it seems that he is now painfully aware of which type of family Walter and Florence each belong to, and that his hope of being with Florence in the future has been lost.

Yes, Paul is 5, which makes Florence about 11.

Yes, Paul is 5, which makes Florence about 11. I have a bit of a problem with Walter's age. When he found Florence in the street, she was 6 and he was working for Dombey & Son already. How old would that make him at that time? 12? 14?

That seems like a large age difference for the boy to take such an interest in Florence.

Now, 5 years later, Florence has aged but Walter somehow hasn't? As his character is written, he seems to be the same age, in the same position at Dombey & Son (beginner status; errandboy) and he hasn't changed in the 5 years.

How old do you think Walter is now that Florence is 11?

Linda, I was saddened, too, to read about Walter's inner feelings concerning Florence after the meeting. This could/will possibly change their relationship and not for the better. Once again, Florence may be left without the warmth of a good friendship (if Walter pulls away from the relationship).

I didn't see Paul's walking around upright after helping Walter as something of concern. I saw him as a 5-yr old child who's done something good and knows it. They tend to puff up their chests and get to feeling quite proud of themselves for "doing/being good". It's more of a way of feeling included and well thought of for doing good than it is a thing about power.

But, I will have to think on this aspect, too, because Paul is so unlike a regular 5-yr old.

I haven't yet seen any greed or power struggle within him but maybe this was the beginning? Thank you for that insight. I'm going to think about it and watch for it as we read forward.

Tristam, maybe Florence will have a larger role as we move forward. So far, we've just seen her in the background as a way of showing us how neglected and unnecessary she is to the family and to Dombey & Son but Dickens must have a purpose for her and a role for her to play, don't you think? She's too large of a background figure to just melt away into the story. Guess we'll find out soon. :D

Petra, I hadn't thought of Walter's change, or lack of change, over the past 5 years. But you're right, now that you point it out, it doesn't seem like he has changed at all. And it seems he is in the same position at Dombey and Son. I had thought he was around 11 or 12 when he started working, but I think that was just a feeling I had, I'm not sure the book ever said exactly how old he was. So in my mind, that would make him around 16 or 17 now. I don't know, back in those times I don't think a 17 year old boy looking at an 11 year old girl would be of any concern? But it would be by today's standards, of course.

Petra, I hadn't thought of Walter's change, or lack of change, over the past 5 years. But you're right, now that you point it out, it doesn't seem like he has changed at all. And it seems he is in the same position at Dombey and Son. I had thought he was around 11 or 12 when he started working, but I think that was just a feeling I had, I'm not sure the book ever said exactly how old he was. So in my mind, that would make him around 16 or 17 now. I don't know, back in those times I don't think a 17 year old boy looking at an 11 year old girl would be of any concern? But it would be by today's standards, of course.Petra: "I didn't see Paul's walking around upright after helping Walter as something of concern. I saw him as a 5-yr old child who's done something good and knows it."

Yes, I didn't think Paul did this because he knew he had power, but instead as you stated, that he felt he had done some good by his father. My previous post made it sound like he knew he had power, and I don't think that was my intention. I was cringing at the thought, though, that it was the use of money and power that his father used to show Paul what being a good Dombey meant. These are the lessons Paul is learning at this early age, and it is unfortunate.

Petra, as to Walter potentially pulling away from Florence, that is a good observation of what may happen after having this meeting. It will be something to watch for.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Pickwickians,welcome to the thread on Chapters 8 to 10 of Dombey and Son. In Chapter 8 we get to know more about young Paul's upbringing and education, and we witness how he is sent t..."

think that both Dombey and Paul are successful literary figures in that they offer some psychological interest, whereas Florence is just another of those female Dickensian paragons of virtue, submission and endurance Victorian readers could project their sentimentality upon.

Yes, from what I understand of Dickens, he is known for writing Florence type characters, only to show how they evolve from one end of the spectrum to the other-the latter spectrum representing improved livelihood? Where the downtrodden (not saying Florence is), especially women, are essentially thrown to the wayside by Victorian society; Dickens sheds a positive light on them.

Petra wrote: "Yes, Paul is 5, which makes Florence about 11.

I have a bit of a problem with Walter's age. When he found Florence in the street, she was 6 and he was working for Dombey & Son already. How old wou..."

The feelings which have transpired since Walter's first interaction with Florence gave me pause for concern too not knowing how old Walter was at the time...Or even currently for that matter. I don't think he can be more than 16, in the present, but his interest in an 11 year old girl still seems inappropriate...No?

In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and it's what you must have looked for, often."

In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and it's what you must have looked for, often."I didn't understand what Mrs. Wickham meant to imply, or say, here?

Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."

Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."Oh, come now. I see her as a lot more than that.

And of course there is the benefit to Dombey of getting her out of his hair, and being able to dismiss the nurses entirely.

Linda wrote: "Some of my favorite passages and descriptions occurred in chapter 8, especially descriptions of Mrs. Pipchin and young Paul. I will record them later when I have the copy of my book handy."

Linda wrote: "Some of my favorite passages and descriptions occurred in chapter 8, especially descriptions of Mrs. Pipchin and young Paul. I will record them later when I have the copy of my book handy."If you're using a phone or tablet maybe you can't do this, but I always keep a copy of the Gutenberg copy of D&S open in a separate tab of my browser so I can search for and then cut and paste passages into posts. Very quick and easy.

If you're not familiar with Gutenberg, just open a new browser tab, go to

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/821?m...

and click on Read this Book Online.

Everyman wrote: "I always keep a copy of the Gutenberg copy of D&S open in a separate tab of my browser so I can search for and then cut and paste passages into posts. Very quick and easy"

Everyman wrote: "I always keep a copy of the Gutenberg copy of D&S open in a separate tab of my browser so I can search for and then cut and paste passages into posts. Very quick and easy"Thanks so much, Everyman! This will be very useful indeed. Usually I have my book held open in front of me while I keep my keyboarding skills honed typing in passages I find relevant.

Now I can't remember who mentioned it here, possibly in a previous thread, about little Paul seeming to be like an old man. This was one of my favorite lines, if only because I was taken aback by his comparison to a "goblin":

Now I can't remember who mentioned it here, possibly in a previous thread, about little Paul seeming to be like an old man. This was one of my favorite lines, if only because I was taken aback by his comparison to a "goblin":And he went on, warming his hands again, and thinking about them, like an old man or a young goblin.

Loved this exchange between Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. Paul is not afraid to speak his mind, that is for sure.

'Well, Sir,' said Mrs Pipchin to Paul, 'how do you think you shall like me?'

'I don't think I shall like you at all,' replied Paul. 'I want to go away. This isn't my house.'

'No. It's mine,' retorted Mrs Pipchin.

'It's a very nasty one,' said Paul.

In reference to the differences in meals everyone gets, I wonder if Mrs. Pipchin gets her meals hot and unlimited because it is her house and she feels she deserves them more than the others, or if she believes she is toughening up the children by way of limiting their food to cold bread and such?

For tea there was plenty of milk and water, and bread and butter, with a little black tea-pot for Mrs Pipchin and Berry, and buttered toast unlimited for Mrs Pipchin, which was brought in, hot and hot, like the chops. Though Mrs Pipchin got very greasy, outside, over this dish, it didn't seem to lubricate her internally, at all...

And again, little Paul is not afraid to say what is on his mind. I love the innocent remark about the hot chops.

Once she asked him, when they were alone, what he was thinking about.

'You,' said Paul, without the least reserve.

'And what are you thinking about me?' asked Mrs Pipchin.

'I'm thinking how old you must be,' said Paul.

'You mustn't say such things as that, young gentleman,' returned the dame. 'That'll never do.'

'Why not?' asked Paul.

'Because it's not polite,' said Mrs Pipchin, snappishly.

'Not polite?' said Paul.

'No.'

'It's not polite,' said Paul, innocently, 'to eat all the mutton chops and toast', Wickam says.

Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and ..."

Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and ..."Ami, I reviewed this conversation and I am at a loss for what Mrs. Wickham meant by this.

Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and ..."

Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss Berry, and ..."I think she means that Mrs Pipchin has not long to live, and that Miss Berry will benefit from her death. Just beforehand, Mrs Wickham signalled towards Florence and Mrs P, pointing them out as two people to whom Paul had taken a fancy, and therefore would probably die soon. In Mrs P's case, is her implication, it wouldn't be such a loss.

Linda wrote: "Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss..."

Linda wrote: "Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss..."Pip wrote: "Ami wrote: "In Chapter 8 during the conversation between Mrs. Wickham and Miss Berry, while discussing Betsey Jane and young Paul, Mrs. Wickham ends with, Good night! Your aunt is an old lady, Miss..."

Ahhhh, okay! Thank you so much! The "looked for, often" segment really threw me!

Linda wrote: "Now I can't remember who mentioned it here, possibly in a previous thread, about little Paul seeming to be like an old man. This was one of my favorite lines, if only because I was taken aback by ..."

Linda wrote: "Now I can't remember who mentioned it here, possibly in a previous thread, about little Paul seeming to be like an old man. This was one of my favorite lines, if only because I was taken aback by ..."I laughed out loud while reading Paul's quick witted retorts to Mrs. Pipchin. I love this kid, so precocious!

Somebody also questioned in a previous thread if Paul would share the same interest level as Mr. Dombey Sr. in regards to the business. From their exchange on the subject of money in Chapter 8, when Paul asks Dombey What is money...what is it after all...what can it do; Dombey answers, Money, Paul, can do anything. Paul hones in on the word "anything" and asks Why didn't money save me my mamma?"

One Dombey clearly sees money having its limitations, while the other does not (technically). Young Paul is a bit more soulful on the subject matter. It leads me to believe Paul will have opposing views on their approach to the Dombey and Son business also.

Hmm....in Chapter 1 Paul is just born and Florence is six. Then in Chapter 4 we have this about Walter;

Hmm....in Chapter 1 Paul is just born and Florence is six. Then in Chapter 4 we have this about Walter;"Here he lived too, in skipper-like state, all alone with his nephew Walter: a boy of fourteen who looked quite enough like a midshipman, to carry out the prevailing idea."

In Chapter 5 Richards has been with the Dombeys 6 months which could make Florence seven years old by then:

'During the six months or so, Richards, which have seen you an inmate of this house, you have done your duty.

So after Dickens tells us that Walter is 14 we have Richards only with the Dombeys six months, I think Paul would have been six or seven months old by then.

In the beginning of Chapter 8 Paul is almost five:

"Thus Paul grew to be nearly five years old. He was a pretty little fellow; though there was something wan and wistful in his small face, that gave occasion to many significant shakes of Mrs Wickam's head, and many long-drawn inspirations of Mrs Wickam's breath."

If Paul is five, then Florence is eleven and Walter would be 19. Dickens says in Chapter 9:

"Such was his condition at the Pipchin period, when he looked a little older than of yore, but not much; and was the same light-footed, light-hearted, light-headed lad, as when he charged into the parlour at the head of Uncle Sol and the imaginary boarders, and lighted him to bring up the Madeira."

So I guess 19 year old Walter has been thinking about 11 year old Florence. Seems odd to me.

Pip wrote: "I think she means that Mrs Pipchin has not long to live, and that Miss Berry will benefit from her death. Just beforehand, Mrs Wickham signalled towards Florence and Mrs P, pointing them out as two people to whom Paul had taken a fancy, and therefore would probably die soon. In Mrs P's case, is her implication, it wouldn't be such a loss."

Pip wrote: "I think she means that Mrs Pipchin has not long to live, and that Miss Berry will benefit from her death. Just beforehand, Mrs Wickham signalled towards Florence and Mrs P, pointing them out as two people to whom Paul had taken a fancy, and therefore would probably die soon. In Mrs P's case, is her implication, it wouldn't be such a loss."Ah yes, that makes sense. Thanks Pip!

Ami wrote: "I laughed out loud while reading Paul's quick witted retorts to Mrs. Pipchin. I love this kid, so precocious!"

Ami wrote: "I laughed out loud while reading Paul's quick witted retorts to Mrs. Pipchin. I love this kid, so precocious!"I am loving little Paul too! :)

@Linda and Ami - it took me a while and several readings of that section to come to my conclusion, though I'm still not 100% sure it's the right one!

@Linda and Ami - it took me a while and several readings of that section to come to my conclusion, though I'm still not 100% sure it's the right one!

Kim wrote: "So I guess 19 year old Walter has been thinking about 11 year old Florence. Seems odd to me."

Kim wrote: "So I guess 19 year old Walter has been thinking about 11 year old Florence. Seems odd to me."Good deduction there, Kim. I missed the part where it said that Walter was 14 at the time.

So yeah, 19 and 11?? That seems odd to me too.

Linda wrote: "then to see young Paul walking around upright afterward as if to show off his power was quite disheartening to see in such a young child."

Linda wrote: "then to see young Paul walking around upright afterward as if to show off his power was quite disheartening to see in such a young child."And yet what a good and striking detail of Dickens to put into the story. It is exactly details like this, i.e. things that show that Paul is influenced by his father as a role model, and by other people and probably bad examples around him, that make little Paul appear like a real child, for all his quirks and idiosyncrasies (e.g. shunning the companionship of children his age and seeking that of older people). That is why I think him an interesting character, and why his fate is capable of moving me.

Petra wrote: "I have a bit of a problem with Walter's age. When he found Florence in the street, she was 6 and he was working for Dombey & Son already. How old would that make him at that time? 12? 14?

Petra wrote: "I have a bit of a problem with Walter's age. When he found Florence in the street, she was 6 and he was working for Dombey & Son already. How old would that make him at that time? 12? 14?That seems like a large age difference for the boy to take such an interest in Florence. "

In Chapter 4, when Walter is first introduced, his age is given as 14 years, which - at that time - makes him more than twice as old as Florence.

Petra wrote: "Yes, Paul is 5, which makes Florence about 11.

Petra wrote: "Yes, Paul is 5, which makes Florence about 11. I have a bit of a problem with Walter's age. When he found Florence in the street, she was 6 and he was working for Dombey & Son already. How old wou..."

Knowing the story already but not wanting to be a bean-spiller, I'll just say here that Florence is going to be one of the major characters in the book - I hope it's okay to say that much -, but still I think that Dickens somehow fails to imbue her with a life of her own, at least to me.

Linda wrote: "Yes, I didn't think Paul did this because he knew he had power, but instead as you stated, that he felt he had done some good by his father. My previous post made it sound like he knew he had power, and I don't think that was my intention. I was cringing at the thought, though, that it was the use of money and power that his father used to show Paul what being a good Dombey meant. These are the lessons Paul is learning at this early age, and it is unfortunate.."

Linda wrote: "Yes, I didn't think Paul did this because he knew he had power, but instead as you stated, that he felt he had done some good by his father. My previous post made it sound like he knew he had power, and I don't think that was my intention. I was cringing at the thought, though, that it was the use of money and power that his father used to show Paul what being a good Dombey meant. These are the lessons Paul is learning at this early age, and it is unfortunate.."I'd also say that in Paul, there is an innocent pride in having done something good, but still this pride can be worked on by Mr. Dombey and be turned into something less innocent and endearing. And this seems so realistic: Children are all innocence, and this is why they can be spoiled by adults who impose their own views on things on them.

Ami wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Pickwickians,

Ami wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Pickwickians,welcome to the thread on Chapters 8 to 10 of Dombey and Son. In Chapter 8 we get to know more about young Paul's upbringing and education, and we witness..."

I think that first of all, Walter's fascination with Florence is fuelled by that atmosphere of chivalrous romance that was part and parcel of the Brown incident. Hence the fairy-tale-motifs connected with it. And then we read something this:

"But the sentiment of all this was as boyish and innocent as could be. Florence was very pretty, and it is pleasant to admire a pretty face. Florence was defenceless and weak, and it was a proud thought that he had been able to render her any protection and assistance. Florence was the most grateful little creature in the world, and it was delightful to see her bright gratitude beaming in her face. Florence was neglected and coldly looked upon, and his breast was full of youthful interest for the slighted child in her dull, stately home."

So it is clearly some kind of innocent damsel-in-distress romanticism that is at the bottom of Walter's preoccupation with Florence. At the same time, I'd say that this is a typically Victorian gender perception: Women have to be helpless, defenseless and enduring, a men tend to save them from all sorts of threats.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."Oh, come now. I see her as a lot more than that.

And of course there is the benefit to Dombey of getting her out..."

I did not want to seem unfair: By referring to Florence as a social appendix, I tried to render the idea that Dombey and Mrs. Chick might have entertained of Florence.

Just to say I'm not able to reread Dombey as I have so much on my plate at the moment, but I'm really enjoying reading everyone's comments :-)

Just to say I'm not able to reread Dombey as I have so much on my plate at the moment, but I'm really enjoying reading everyone's comments :-)Little Paul Dombey is one of my favourite Dickens characters; it's the cheekily innocent (or do I mean innocently cheeky?) battles of words with Mrs Pipchin which really do it for me.

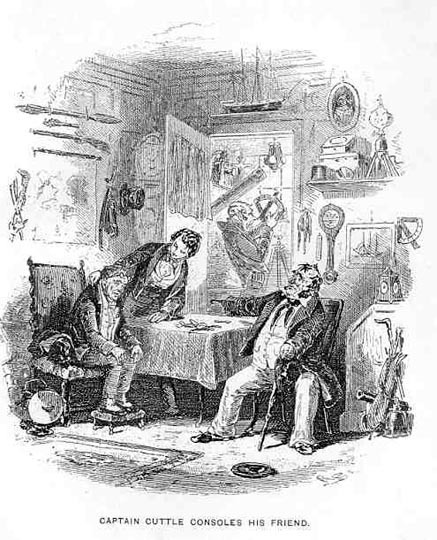

D&S if full of unlikely partnerships, and these two really set the standard. I absolutely love the illustration that Kim posted of the two of them sitting by the fire during the "mutton chops" conversation, although I understand that Dickens himself was not happy with poor Phiz's work.

Kim wrote: "Hmm....in Chapter 1 Paul is just born and Florence is six. Then in Chapter 4 we have this about Walter;

Kim wrote: "Hmm....in Chapter 1 Paul is just born and Florence is six. Then in Chapter 4 we have this about Walter;"Here he lived too, in skipper-like state, all alone with his nephew Walter: a boy of fourt..."

Thank you, Kim, for setting the ages straight. After all, it seems that you are pretty good at math no matter what you say ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix,..."Oh, come now. I see her as a lot more than that.

And of course there is the benefit to Dombey o..."

I think Dombey sees her as even less than a social appendix, Tristram (love the expression, by the way!). In fact, I don't think he really sees her full stop.

Tristram wrote: "Florence is just another of those female Dickensian paragons of virtue, submission and endurance Victorian readers could project their sentimentality upon."

Tristram wrote: "Florence is just another of those female Dickensian paragons of virtue, submission and endurance Victorian readers could project their sentimentality upon." Why is it I wonder that in every single book we read together I end up having to say, usually about the female in the book, poor, poor....whoever. In this case, poor, poor Florence. Grump.

Oh, and as to math, thanks to your Walter was twice as old comment I had to figure out if Walter is twice as old as Florence when she is six why is he nowhere near twice as old as her when she is eleven? And as to how much older is he when she is eleven - twice, a third, a fourth, an eighth, a whatever other fraction is out there. I have no idea.

I felt so sorry for Paul with the comment that Dombey would swap him for another son, because of his health. It tells me that Dombey see everything only as a commodity. Any son would do. The personality is negligible.

I felt so sorry for Paul with the comment that Dombey would swap him for another son, because of his health. It tells me that Dombey see everything only as a commodity. Any son would do. The personality is negligible. The idea that Walter has hopes for himself and Florence one day, even though she is 11 and Walter 19 at this time, seems a bit bizarre to me too. Therefore, and I hate to say it as I do like Walter, but maybe he is also looking at Florence as a commodity to step up beyond the working class, rather than purely for loves sake. Just as Dombey sees Paul as the final piece in his business empire.

I had to laugh at the description of Major Bagstock, with his Stilton cheese complexion and eyes like a prawn's. Lol. Also, I love the name Mrs MacStinger.

Must dash...

At the beginning of Chapter 8 Dickens says this about Paul and his childhood diseases:

At the beginning of Chapter 8 Dickens says this about Paul and his childhood diseases:"Every tooth was a break-neck fence, and every pimple in the measles a stone wall to him. He was down in every fit of the hooping-cough, and rolled upon and crushed by a whole field of small diseases, that came trooping on each other's heels to prevent his getting up again. Some bird of prey got into his throat instead of the thrush; and the very chickens turning ferocious—if they have anything to do with that infant malady to which they lend their name—worried him like tiger-cats."

Now Dickens isn't going to mention chickenpox and chickens lending their name to that malady without getting me wondering why it is called chickenpox. Here you go:

"The name chickenpox has been around for centuries, and there are a number of theories as to how it got its name. One is that it's from the blisters that are seen with the illness. These red spots — which are about 1/5 inch to 2/5 inch (5mm to 10mm) wide — were once thought to look like chickpeas (garbanzo beans).

Another theory is that the rash of chickenpox looks like the peck marks caused by a chicken. Other suggestions include the designation chicken for a child (i.e., literally 'child pox'), a corruption of itching-pox, or the idea that the disease may have originated in chickens. Samuel Johnson explained the designation as "from its being of no very great danger."

Tristram wrote: "Knowing the story already but not wanting to be a bean-spiller, I'll just say here that Florence is going to be one of the major characters in the book..."

Tristram wrote: "Knowing the story already but not wanting to be a bean-spiller, I'll just say here that Florence is going to be one of the major characters in the book..."I was wondering if you find it hard not to spill the beans. Having read all the books, I am having more trouble not to give anything away with this one than any of the ones that came before it.

Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,

Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,“I hope you like Mrs. Pipchin’s establishment. It is from the life and I was there”.

She was modeled after Elizabeth Roylance, a woman "long known to our family" who Dickens lodged with while his parents were doing time in Marshalsea Prison for debt. He had to use his six shillings per week wage from the Blacking Factory to pay for his lodging and meals.

On Sundays he and Fanny would visit the family in the Marshalsea. On one of these occassions, Dickens broke down in tears from despair and loneliness and so a new lodging place in Lant Street was found for him. Living closer to the prison now, he was able to have breakfast and supper with the family at the prison.

This is what Dickens wrote to John Forster about living with Elizabeth Roylance:

"The key of the house was sent back to the landlord, who was very glad to get it; and I (small Cain that I was, except that I had never done harm to any one) was handed over as a lodger to a reduced old lady, long known to our family, in Little College Street, Camden-town, who took children in to board, and had once done so at Brighton; and who, with a few alterations and embellishments, unconsciously began to sit for Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey when she took in me.

"She had a little brother and sister under her care then; somebody's natural children, who were very irregularly paid for; and a widow's little son. The two boys and I slept in the same room. My own exclusive breakfast, of a penny cottage loaf and a penny-worth of milk, I provided for myself. I kept another small loaf, and a quarter of a pound of cheese, on a particular shelf of a particular cupboard; to make my supper on when I came back at night. They made a hole in the six or seven shillings, I know well; and I was out at the blacking-warehouse all day, and had to support myself upon that money all the week. I suppose my lodging was paid for, by my father. I certainly did not pay it myself; and I certainly had no other assistance whatever (the making of my clothes, I think, excepted), from Monday morning until Saturday night. No advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from any one that I can call to mind, so help me God.

"Sundays, Fanny and I passed in the prison. I was at the academy in Tenterden Street, Hanover Square, at nine o'clock in the morning, to fetch her; and we walked back there together, at night.

"I was so young and childish, and so little qualified—how could I be otherwise?—to undertake the whole charge of my own existence, that, in going to Hungerford Stairs of a morning, I could not resist the stale pastry put out at half-price on trays at the confectioners' doors in Tottenham Court Road; and I often spent in that the money I should have kept for my dinner.

"My rescue from this kind of existence I considered quite hopeless, and abandoned as such, altogether; though I am solemnly convinced that I never, for one hour, was reconciled to it, or was otherwise than miserably unhappy. I felt keenly, however, the being so cut off from my parents, my brothers and sisters, and, when my day's work was done, going home to such a miserable blank; and that, I thought, might be corrected. One Sunday night I remonstrated with my father on this head, so pathetically, and with so many tears, that his kind nature gave way. He began to think that it was not quite right. I do believe he had never thought so before, or thought about it. It was the first remonstrance I had ever made about my lot, and perhaps it opened up a little more than I intended. A back-attic was found for me at the house of an insolvent-court agent, who lived in Lant Street in the borough, where Bob Sawyer lodged many years afterwards. A bed and bedding were sent over for me, and made up on the floor. The little window had a pleasant prospect of a timber-yard; and when I took possession of my new abode I thought it was a Paradise."

In October 1846 Dickens, writing to his friend John Forster while he was writing the beginning chapters of Dombey and Son, expressed disappointment in the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin for the novel prepared by his illustrator, Hablot Browne:

"I am really distressed by the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark. Good Heaven! in the commonest and most literal construction of the text, it is all wrong. She is described as an old lady, and Paul's 'miniature armchair' is mentioned more than once. He ought to be sitting in a little arm-chair down in a corner of the fireplace, staring up at her. I can't say what pain and vexation it is to be so utterly misrepresented. I would cheerfully have given a hundred pounds to have kept this illustration out of the book. He never could have got that idea of Mrs. Pipchin if he had attended to the text. Indeed I think he does better without the text; for then the notion is made easy to him in short description, and he can't help taking it in."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Knowing the story already but not wanting to be a bean-spiller, I'll just say here that Florence is going to be one of the major characters in the book..."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Knowing the story already but not wanting to be a bean-spiller, I'll just say here that Florence is going to be one of the major characters in the book..."I was wondering if you ..."

I'm obviously not answering for Tristram (gods forbid!!) but I always find it useful with a book I've finished when the discussion leader gives a brief synopsis at the start of each section. That makes it much easier to keep your beans relatively unspilt without having to go back and check your copy (especially difficult within e-reader).

Kim wrote: "Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,

Kim wrote: "Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,“I hope you like Mrs. Pipchin’s es..."

I wonder if the fact that Mrs Pipchin was modelled on a real-life character had something to do with his unhappiness with the illustration? Dickens would obviously have a very clear picture of the lady in his mind. On the other hand, it does seem that he is more concerned with the height of Paul's chair than anything else....

Kim wrote: "Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,

Kim wrote: "Dickens told John Forster that Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey was modeled after somebody he had relations with in his own life. On November 4, 1846, he tells Forster,“I hope you like Mrs. Pipchin’s es..."

Kim

My thanks also for the math to figure out the ages of Walter, Florence and Paul. The posting of the pictures is great and your detailed research keeps me up to date with much I would miss or misunderstand.

I don't really find the age difference too difficult to deal with at all. Walter is not presented, in any way, like a predator. If anything, he seems a bit naïve and childish. His kindness and connection with his "family" is completely natural, so why would a happy child who as a good family not work as a companion and friend to Florence. If we add 15 years to each of their lives the accepted Victorian age of marriage between a man and woman fades into a non question. Yes, they are young, but both are orphans in many ways. Walter is an orphan by virtue of his circumstance and Florence by her father's alienation of any consistent degree of love towards her.

Certainly Quilp's interest in Little Nell was creepy but I would suggest that Major Bagstock's presentation is rather Freudian. A look at how he gets when excited is, well ... interesting.

While I'm on my horse to rescue Florence I will add that I'm enjoying her portrayal so far. While she is kind, innocent and sweet, she is not sugary. Of the female characters of her age up to D&S she is the best creation. She is able to exist in a cold, loveless household, she is able to remain calm and rational in a time of danger and fear and she is able to face her father's engherzig (thanks Tristram) with grace and strength.

D&S presents the reader with another series of schools from Hell. Can anyone recall any formal school so far in Dickens' novels that is a pleasant place to attend? In TOCS we have the school teacher who befriends Nell and her grandfather and then meets with them later in the novel, but that's all I can recall.

D&S presents the reader with another series of schools from Hell. Can anyone recall any formal school so far in Dickens' novels that is a pleasant place to attend? In TOCS we have the school teacher who befriends Nell and her grandfather and then meets with them later in the novel, but that's all I can recall.

Linda wrote: "In reference to the differences in meals everyone gets, I wonder if Mrs. Pipchin gets her meals hot and unlimited because it is her house and she feels she deserves them more than the others, or if she believes she is toughening up the children by way of limiting their food to cold bread and such?"

Linda wrote: "In reference to the differences in meals everyone gets, I wonder if Mrs. Pipchin gets her meals hot and unlimited because it is her house and she feels she deserves them more than the others, or if she believes she is toughening up the children by way of limiting their food to cold bread and such?"Economy. Cheapskating. Her whole household is about her comfort, not the welfare of the children.

Linda wrote: "And again, little Paul is not afraid to say what is on his mind. "

Linda wrote: "And again, little Paul is not afraid to say what is on his mind. "That's an interesting point nicely demonstrated with passages.

Where does that come from? How did he get that way? Partly, perhaps, nature. But a significant part, I suggest, from Richards allowing, even encouraging, him to speak his mind, to become his own person.

How different from the people his father turns his care over to. One has to wonder whether he will continue to speak his mind, or whether it will be beaten out of him by adults who resent uppity children and stamp them down assiduously.

Kim wrote: "I also found the first working drawing that was done but not used:

Kim wrote: "I also found the first working drawing that was done but not used:"

While it may seem strange that this and the actual print are mirror-images, that's how the artists had to work. The copperplate engraving had to be backward so as to print properly on the paper when it was inked and pressed into the page. So the one you said wasn't used was probably the sketch which he (or his engraver if he didn't do his own engraving) used as the basis for engraving the plate to make the print which we see at the top of the post.

Ami wrote: "One Dombey clearly sees money having its limitations, while the other does not (technically). "

Ami wrote: "One Dombey clearly sees money having its limitations, while the other does not (technically). "Very nice comparison of Paul's and Dombey's thoughts.

Tristram wrote: "o it is clearly some kind of innocent damsel-in-distress romanticism that is at the bottom of Walter's preoccupation with Florence."

Tristram wrote: "o it is clearly some kind of innocent damsel-in-distress romanticism that is at the bottom of Walter's preoccupation with Florence."Agreed. Romantic, yes, in the classical meaning of romantic. Sexual, no.

Kim wrote: "Why is it I wonder that in every single book we read together I end up having to say, usually about the female in the book, poor, poor....whoever. In this case, poor, poor Florence. "

Kim wrote: "Why is it I wonder that in every single book we read together I end up having to say, usually about the female in the book, poor, poor....whoever. In this case, poor, poor Florence. "Because you don't accept the concept of womanhood prevalent in Dickens's day

Peter wrote: "D&S presents the reader with another series of schools from Hell. ."

Peter wrote: "D&S presents the reader with another series of schools from Hell. ."Which, if I recall my biography correctly, is what Dickens endured in the little formal schooling he had.

I don't think that schools in his day were, or were intended to be, enjoyable places. Not as bad as in NN, of course, but not a whole lot better, either.

Indeed, it's not just Dickens, is it? Look at the schools in other books of the time. Jane Eyre, for example. Becky Sharp's experiences in Vanity Fair. What nice schools are there in ANY Victorian literature?

Peter wrote: "I don't really find the age difference too difficult to deal with at all. Walter is not presented, in any way, like a predator. If anything, he seems a bit naïve and childish. His kindness and connection with his "family" is completely natural, so why would a happy child who as a good family not work as a companion and friend to Florence. If we add 15 years to each of their lives the accepted Victorian age of marriage between a man and woman fades into a non question. Yes, they are young, but both are orphans in many ways. Walter is an orphan by virtue of his circumstance and Florence by her father's alienation of any consistent degree of love towards her."

Peter wrote: "I don't really find the age difference too difficult to deal with at all. Walter is not presented, in any way, like a predator. If anything, he seems a bit naïve and childish. His kindness and connection with his "family" is completely natural, so why would a happy child who as a good family not work as a companion and friend to Florence. If we add 15 years to each of their lives the accepted Victorian age of marriage between a man and woman fades into a non question. Yes, they are young, but both are orphans in many ways. Walter is an orphan by virtue of his circumstance and Florence by her father's alienation of any consistent degree of love towards her."Good points here, Peter.

Everyman wrote: "Economy. Cheapskating. Her whole household is about her comfort, not the welfare of the children."

Everyman wrote: "Economy. Cheapskating. Her whole household is about her comfort, not the welfare of the children."That's what I suspected, but didn't want to assume.

welcome to the thread on Chapters 8 to 10 of Dombey and Son. In Chapter 8 we get to know more about young Paul's upbringing and education, and we witness how he is sent to Brighton, being rather poorly and frail. His sister is allowed to join him as a social appendix, and he even has a new nurse, a rather melancholy woman by the name of Wickam, who does not seem to have taken too kindly to him for she entertains the bleakest supersticious reservations on his effect on those he loves. It's quite funny when she says that she is quite relieved to find young Paul has not taken such a fancy to her.

Yet I'm asking myself what is actually the matter with Paul. He seems to be quite a gloomy and sombre child, though not at all mean. In conjunction with Mrs. Pipchin and the chimney imagery he really seems like one of those changelings people used to be afraid of. Can anyone, by the way, tell for sure how many years have passed between this and the previous chapter? How old is Paul, how old is Florence?

Chapters 9 and 10 tell us of new difficulties waiting for Sol Gills and Walter. He has run up large debts in order to help his brother but due to his lack of business success, he is in a fix now.

In Chapter 10 we get to know a little bit more about Major Bagstock, who cannot get over his neglect by Miss Tox and who assumes that Miss Tox is trying to entangle Mr. Dombey into wedlock. Here again the question of how many years have gone past will be important because I can hardly imagine that the Major would have waited four or five years without taking action to reassert his position in Miss Tox's life.

It is interesting that Mr. Dombey uses Walter and Sol's situation to help them and to do this in the name of his son in order to teach him a lesson on the power and importance of money. Usually, Dickens's capitalists are rather penny-pinching but Mr. Dombey has discovered the pleasure that lies in being generous with regard to boosting his feeling of self-improtance and power.

I think that both Dombey and Paul are successful literary figures in that they offer some psychological interest, whereas Florence is just another of those female Dickensian paragons of virtue, submission and endurance Victorian readers could project their sentimentality upon.