The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR, Chp. 01-05

Before we start with the events proper of Chapter 2, I must say that I forgot mentioning the fact that the young man – the prepossessing, nice one – left the Inn before Sol started his memorable story, and that Joe let slip some remarks on the young man’s being in love, which is why he is walking all the way to London, his steed having gone lame. Of course, Joe is rebuked – rightly, in this case, I’d say – for his indiscretion by his father and his cronies.

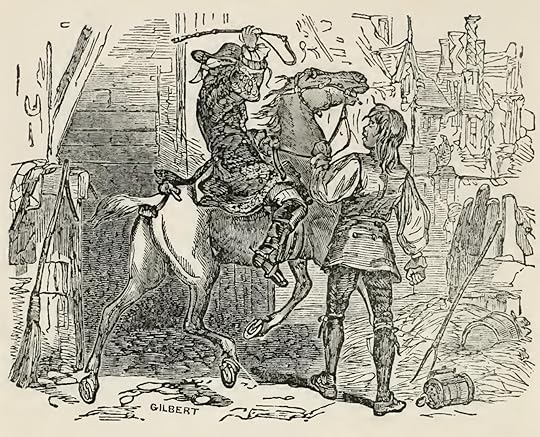

The sinister stranger, after Sol has finished his story, says that it surely is a strange narration, stranger still if it will end one day as the parish-clerk predicts, with the exposure of the murderer. He then becomes impatient of taking his leave, but – as the narrator aptly points out – the only thing our landlord is not slow about is when he sees a guest willing to pay his bill. Once outside, the sinister stranger is detained by Joe, who advises him not to trust himself to his horse on such a dark and stormy – a little bow to Bulwer-Lytton on my part – night but to stay at the Inn. The stranger, however, detests this advice as he does what he regards as Joe’s scrutinizing look, and on departing he beats the young man on the head with the butt end of his whip.

Our narrator does not linger with the humiliated Joe, but takes us, as invisible stowaways on the journey with the mysterious stranger, who rides with a vengeance but who nevertheless seems to know or guess his way. There is some urge that seems to drive him on and on, regardless of the bad conditions of the weather and the road, when suddenly his progress is blocked by a vehicle on the road. The rider can check his horse before an accident occurs but the animal is wounded nonetheless, and so he demands a light from the driver of the vehicle, a man who is described as

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

The round and sturdy yeoman will soon be introduced as the locksmith Gabriel Varden, who was originally meant to be the eponymous hero of the novel but for some reason had to cede this honour to Barnaby Rudge. The description above gives you a favourable impression of this character, and it also has something in common with the description of the Maypole, namely the fact that both grew old but not decrepit in body, mind or heart.

Then, the passage above gives us the intrusive narrator again, with his tendency to comment on the characters, and the action and to moralize. Does it add to or detract from the atmosphere here in your eyes?

The mysterious stranger and our locksmith soon engage in a none-too-hearty conversation in the course of which Gabriel wants to take a look at the stranger’s face. Seeing that resistance would involve him into an arduous fight, and that the locksmith is not easy to intimidate, the rider finally gives in and lets the other take a look at him. The narration now contrasts these two characters explicitly, and there is no doubt as to whom we are expected to side with:

And yet, although he has given in to Gabriel’s demand, the stranger, on parting, cannot forbear mentioning that even five minutes before Gabriel will eventually die one day, he will not be closer to his end than he was during their encounter on the nocturnal road. A threat that does not leave too deep an impression on the locksmith. However, when resuming his journey – he came from The Warren, where he had to repair some locks, and was travelling by a third road towards London –, he deems it best to stop at the Maypole, although he had promised his wife not to. After all, his own horse must have suffered, and so it would be good and charitable to give the beast some rest before going to London.

The sinister stranger, after Sol has finished his story, says that it surely is a strange narration, stranger still if it will end one day as the parish-clerk predicts, with the exposure of the murderer. He then becomes impatient of taking his leave, but – as the narrator aptly points out – the only thing our landlord is not slow about is when he sees a guest willing to pay his bill. Once outside, the sinister stranger is detained by Joe, who advises him not to trust himself to his horse on such a dark and stormy – a little bow to Bulwer-Lytton on my part – night but to stay at the Inn. The stranger, however, detests this advice as he does what he regards as Joe’s scrutinizing look, and on departing he beats the young man on the head with the butt end of his whip.

Our narrator does not linger with the humiliated Joe, but takes us, as invisible stowaways on the journey with the mysterious stranger, who rides with a vengeance but who nevertheless seems to know or guess his way. There is some urge that seems to drive him on and on, regardless of the bad conditions of the weather and the road, when suddenly his progress is blocked by a vehicle on the road. The rider can check his horse before an accident occurs but the animal is wounded nonetheless, and so he demands a light from the driver of the vehicle, a man who is described as

”a round, red-faced, sturdy yeoman, with a double chin, and a voice husky with good living, good sleeping, good humour, and good health. He was past the prime of life, but Father Time is not always a hard parent, and, though he tarries for none of his children, often lays his hand lightly upon those who have used him well; making them old men and women inexorably enough, but leaving their hearts and spirits young and in full vigour.”

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

The round and sturdy yeoman will soon be introduced as the locksmith Gabriel Varden, who was originally meant to be the eponymous hero of the novel but for some reason had to cede this honour to Barnaby Rudge. The description above gives you a favourable impression of this character, and it also has something in common with the description of the Maypole, namely the fact that both grew old but not decrepit in body, mind or heart.

Then, the passage above gives us the intrusive narrator again, with his tendency to comment on the characters, and the action and to moralize. Does it add to or detract from the atmosphere here in your eyes?

The mysterious stranger and our locksmith soon engage in a none-too-hearty conversation in the course of which Gabriel wants to take a look at the stranger’s face. Seeing that resistance would involve him into an arduous fight, and that the locksmith is not easy to intimidate, the rider finally gives in and lets the other take a look at him. The narration now contrasts these two characters explicitly, and there is no doubt as to whom we are expected to side with:

”Perhaps two men more powerfully contrasted, never opposed each other face to face. The ruddy features of the locksmith so set off and heightened the excessive paleness of the man on horseback, that he looked like a bloodless ghost, while the moisture, which hard riding had brought out upon his skin, hung there in dark and heavy drops, like dews of agony and death.”

And yet, although he has given in to Gabriel’s demand, the stranger, on parting, cannot forbear mentioning that even five minutes before Gabriel will eventually die one day, he will not be closer to his end than he was during their encounter on the nocturnal road. A threat that does not leave too deep an impression on the locksmith. However, when resuming his journey – he came from The Warren, where he had to repair some locks, and was travelling by a third road towards London –, he deems it best to stop at the Maypole, although he had promised his wife not to. After all, his own horse must have suffered, and so it would be good and charitable to give the beast some rest before going to London.

Here’s what happens in Chapter 3: When Gabriel arrives at the Maypole, he finds the company’s conversation dominated by the sinister stranger and his possible intentions. Joe is indignant at the treatment he has received at the stranger’s hands, and naturally, he yearns for an occasion to pay back this humiliation. His father’s rebukes make him even angrier because he sees the way that he is being treated by his father as the reason for strangers like that rider not paying any respect to him, and he finally bursts out that one of these days, he will no longer bear being put down but leave his father in order to obtain the freedom that becomes his years, and start his own life. Here are some things Joe says,

QUESTIONS

Obviously, young Willet is going to rebel against his father, and this might be interesting seeing that the broader canvas of the novel is some kind of rebellion. What does the way Joe expresses his feelings and thoughts tell us about his character and the reasons for his anger? What are we probably supposed to feel? Is he an unruly son who does not know his place?

Gabriel tries to mediate between the father and the son, but he makes no lasting impression on the former and also fails to convince the latter, although the son understands Gabriel’s arguments. What does the mediator role indicate about Gabriel and his potential role in the novel? What does it say about him as a father?

Speaking of Gabriel as a father, it’s high time we mentioned that twice already Dolly Varden has been referred to by Joe. Dolly Varden is Gabriel’s daughter (and probably one of the finest characters in the novel, but that’s just me talking). It is quite noteworthy that Joe indirectly asks the locksmith not to tell anyone in London about the humiliation he has undergone from the sinister stranger – it being clear that Joe probably has none other but Dolly in mind here.

Eventually, Gabriel has to resume his journey homeward, and while he approaches London little by little, he also approaches sleep not so little by little, but the horse knows its way. Albeit, he is not destined to arrive at his home without further disturbance because he has another chance meeting: This time, it is a man lying prostrate on the road, and another one standing beside him with a light in his hand. This latter is our eponymous hero, Barnaby Rudge, and 23-year old boy, who is mentally disabled. The narrator acquaints us with this fact in the following words:

It is as yet unclear whether Barnaby has witnessed the crime but he knows the victim – the prepossessing young man we have met in the Maypole – as a young man who wanted to go to London to woo his sweetheart. Barnaby is distraught at the sight of the blood – the victim was stabbed with a rapier – but Gabriel finally manages to cajole him into giving him a hand and helping him put the injured man on his vehicle. The locksmith knows that Barnaby’s mother is living nearby and he intends to transport the injured man to her house as the nearest place where help can be got.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Is it not strange that all the people in this novel somehow seem to know each other?

What do you think of the narrator’s description of Barnaby, which I gave above? What might Barnaby’s madness imply or foreshadow? After all, he is the son of a murdered man.

When Gabriel is approaching London, we get a vivid description of the town awaiting him in the darkness, and this description ends with the words ”[…] and London—visible in the darkness by its own faint light, and not by that of Heaven—was at hand”. What does this ominous comment on the narrator’s part imply? Is London, as opposed to the rural outskirts, a place that is shunned by Divine light, a place of man-made destiny?

”’[…] It’s all along of you that he ventured to do what he did. Seeing me treated like a child, and put down like a fool, he plucks up a heart and has a fling at a fellow that he thinks—and may well think too—hasn’t a grain of spirit. […]’”

“’[…] I can bear with you, but I cannot bear the contempt that your treating me in the way you do, brings upon me from others every day. Look at other young men of my age. Have they no liberty, no will, no right to speak? Are they obliged to sit mumchance, and to be ordered about till they are the laughing-stock of young and old? I am a bye-word all over Chigwell, and I say—and it’s fairer my saying so now, than waiting till you are dead, and I have got your money—I say, that before long I shall be driven to break such bounds, and that when I do, it won’t be me that you’ll have to blame, but your own self, and no other.’”

QUESTIONS

Obviously, young Willet is going to rebel against his father, and this might be interesting seeing that the broader canvas of the novel is some kind of rebellion. What does the way Joe expresses his feelings and thoughts tell us about his character and the reasons for his anger? What are we probably supposed to feel? Is he an unruly son who does not know his place?

Gabriel tries to mediate between the father and the son, but he makes no lasting impression on the former and also fails to convince the latter, although the son understands Gabriel’s arguments. What does the mediator role indicate about Gabriel and his potential role in the novel? What does it say about him as a father?

Speaking of Gabriel as a father, it’s high time we mentioned that twice already Dolly Varden has been referred to by Joe. Dolly Varden is Gabriel’s daughter (and probably one of the finest characters in the novel, but that’s just me talking). It is quite noteworthy that Joe indirectly asks the locksmith not to tell anyone in London about the humiliation he has undergone from the sinister stranger – it being clear that Joe probably has none other but Dolly in mind here.

Eventually, Gabriel has to resume his journey homeward, and while he approaches London little by little, he also approaches sleep not so little by little, but the horse knows its way. Albeit, he is not destined to arrive at his home without further disturbance because he has another chance meeting: This time, it is a man lying prostrate on the road, and another one standing beside him with a light in his hand. This latter is our eponymous hero, Barnaby Rudge, and 23-year old boy, who is mentally disabled. The narrator acquaints us with this fact in the following words:

”His hair, of which he had a great profusion, was red, and hanging in disorder about his face and shoulders, gave to his restless looks an expression quite unearthly – enhanced by the paleness of his complexion, and the glassy lustre of his large protruding eyes. Startling as his aspect was, the features were good, and there was something even plaintive in his wan and haggard aspect. But, the absence of the soul is far more terrible in a living man than in a dead one; and in this unfortunate being its noblest powers were wanting.”

It is as yet unclear whether Barnaby has witnessed the crime but he knows the victim – the prepossessing young man we have met in the Maypole – as a young man who wanted to go to London to woo his sweetheart. Barnaby is distraught at the sight of the blood – the victim was stabbed with a rapier – but Gabriel finally manages to cajole him into giving him a hand and helping him put the injured man on his vehicle. The locksmith knows that Barnaby’s mother is living nearby and he intends to transport the injured man to her house as the nearest place where help can be got.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Is it not strange that all the people in this novel somehow seem to know each other?

What do you think of the narrator’s description of Barnaby, which I gave above? What might Barnaby’s madness imply or foreshadow? After all, he is the son of a murdered man.

When Gabriel is approaching London, we get a vivid description of the town awaiting him in the darkness, and this description ends with the words ”[…] and London—visible in the darkness by its own faint light, and not by that of Heaven—was at hand”. What does this ominous comment on the narrator’s part imply? Is London, as opposed to the rural outskirts, a place that is shunned by Divine light, a place of man-made destiny?

In the last chapter, we were approaching London, but now, in Chapter 04, we have finally arrived there, and the scene is the day following the many events and encounters described in the first three chapters. Again, our narrator takes a lot of time in order to give us a description of a house, and this time it is the locksmith’s house and workshop in Clerkenwell, which was back then still a suburb. The narrator makes a point of it that you enter the shop by walking down two or three steps, and that behind the rather dark shop there is a wainscoted parlour from which there seems to be no direct access into the rooms upstairs, i.e. the rooms where the family lives. At second sight, however, two doors can be discovered which provide sole access to the upper part of the building. All in all, the house seems to boast a number of architectural peculiarities, quite like the Maypole, but one striking feature of it is its superior cleanliness, which, for those who know their Dickens, is always a token of good morals and honesty. However, the narrator also states,

What might this tell us of Mrs. Varden, and of a certain type (stereotype?) of woman as the butt of Dickens’s humour?

The chapter then introduces the locksmith’s enchanting daughter Dolly Varden, which is done in a wonderful scene, i.e. when she looks out from one of the upstairs windows:

Mrs. Varden still being asleep, after a night of sitting up for her tardy husband, the locksmith, his daughter and the apprentice Simon Tappertit sit down for an ample breakfast amongst them. During the conversation, Simon, as a mere apprentice, is naturally quiet and keeps in the background, and he listens to the conversation, which centres on the events of the previous night. He learns that the young man found on the road is young Mr. Edward Chester, who wanted to see his sweetheart Emma Haredale, who is in London with her uncle, and who was visiting a masque the night before. Gabriel reports how he went to the masque that very night, after seeing to it that Mr. Chester was put up in Mrs. Rudge’s house, and when he found Miss Emma – characteristically, she did not partake in the entertainment but kept herself aloof in a room apart from the company – and told her about young Edward, the young lady showed signs of highest anxiety, and it was then that he had to leave the masque. There is also talk going on between the father and the daughter about Joe Willet and his intention to leave the Maypole, and this is obviously a topic Dolly is not indifferent at.

Simon Tappertit likewise is deeply affected by what is going on at the breakfast table, and he is definitely more interested in the locksmith’s lovely daughter than in the victuals on display. When he later returns into the workshop, he does not take up the workpiece he has left before breakfasting but he decides that he is in a mood for grinding and so he grinds all the tools. It is obviously on account of Joe Willet that Simon’s readiness to grind and grind has been kindled, and while he is sure that ”’[s]omething will come of this’”, he hopes ”’it mayn’t be human gore!’”

What a suspenseful way of ending a chapter!

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

The chapter devotes a lot of space to a rather long and detailed introduction of Simon Tappertit, whose many quirks and peculiarities mark him as a comic relief figure. Still, we also learn

In what way may this fit in with the general topic of the novel? Although Simon does not like Joe Willet, they do have one thing in common, i.e. their will to resist authority. However, there are several ways in which they are dissimilar – can you think of any?

I also wondered that Simon was described as “old-fashioned”, which seems to run counter to his desire to have it all his own way and to break free from authorities. However, if you look at what his models are, what does this show you?

And what could that bad habit of Sim’s, his tendency to eavesdrop on conversations the locksmith has with his daughter, tell about him?

”Nor was this excellence attained without some cost and trouble and great expenditure of voice, as the neighbours were frequently reminded when the good lady of the house overlooked and assisted in its being put to rights on cleaning days—which were usually from Monday morning till Saturday night, both days inclusive.”

What might this tell us of Mrs. Varden, and of a certain type (stereotype?) of woman as the butt of Dickens’s humour?

The chapter then introduces the locksmith’s enchanting daughter Dolly Varden, which is done in a wonderful scene, i.e. when she looks out from one of the upstairs windows:

”[…] Gabriel stepped into the road, and stole a look at the upper windows. One of them chanced to be thrown open at the moment, and a roguish face met his; a face lighted up by the loveliest pair of sparkling eyes that ever locksmith looked upon; the face of a pretty, laughing, girl; dimpled and fresh, and healthful—the very impersonation of good-humour and blooming beauty.”

Mrs. Varden still being asleep, after a night of sitting up for her tardy husband, the locksmith, his daughter and the apprentice Simon Tappertit sit down for an ample breakfast amongst them. During the conversation, Simon, as a mere apprentice, is naturally quiet and keeps in the background, and he listens to the conversation, which centres on the events of the previous night. He learns that the young man found on the road is young Mr. Edward Chester, who wanted to see his sweetheart Emma Haredale, who is in London with her uncle, and who was visiting a masque the night before. Gabriel reports how he went to the masque that very night, after seeing to it that Mr. Chester was put up in Mrs. Rudge’s house, and when he found Miss Emma – characteristically, she did not partake in the entertainment but kept herself aloof in a room apart from the company – and told her about young Edward, the young lady showed signs of highest anxiety, and it was then that he had to leave the masque. There is also talk going on between the father and the daughter about Joe Willet and his intention to leave the Maypole, and this is obviously a topic Dolly is not indifferent at.

Simon Tappertit likewise is deeply affected by what is going on at the breakfast table, and he is definitely more interested in the locksmith’s lovely daughter than in the victuals on display. When he later returns into the workshop, he does not take up the workpiece he has left before breakfasting but he decides that he is in a mood for grinding and so he grinds all the tools. It is obviously on account of Joe Willet that Simon’s readiness to grind and grind has been kindled, and while he is sure that ”’[s]omething will come of this’”, he hopes ”’it mayn’t be human gore!’”

What a suspenseful way of ending a chapter!

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

The chapter devotes a lot of space to a rather long and detailed introduction of Simon Tappertit, whose many quirks and peculiarities mark him as a comic relief figure. Still, we also learn

”that in the small body of Mr Tappertit there was locked up an ambitious and aspiring soul. As certain liquors, confined in casks too cramped in their dimensions, will ferment, and fret, and chafe in their imprisonment, so the spiritual essence or soul of Mr Tappertit would sometimes fume within that precious cask, his body, until, with great foam and froth and splutter, it would force a vent, and carry all before it. It was his custom to remark, in reference to any one of these occasions, that his soul had got into his head; and in this novel kind of intoxication many scrapes and mishaps befell him, which he had frequently concealed with no small difficulty from his worthy master.”

In what way may this fit in with the general topic of the novel? Although Simon does not like Joe Willet, they do have one thing in common, i.e. their will to resist authority. However, there are several ways in which they are dissimilar – can you think of any?

I also wondered that Simon was described as “old-fashioned”, which seems to run counter to his desire to have it all his own way and to break free from authorities. However, if you look at what his models are, what does this show you?

And what could that bad habit of Sim’s, his tendency to eavesdrop on conversations the locksmith has with his daughter, tell about him?

Our final chapter for this week reintroduces the mysterious stranger we have followed in Chapters 1-3. In the evening, Gabriel pays a visit to Mrs. Rudge in order to learn how the patient is faring and whether he has had any lady visitors. He is not too disappointed when Mrs. Rudge tells him that Mr. Chester only had his father for a visitor but that there was a letter delivered from Miss Emma via Barnaby. The conversation between the locksmith and the widow is interrupted by the appearance of the very stranger that Gabriel met the night before, the very man that most probably attacked young Mr. Chester. At first, the locksmith cannot be too sure of it, because he is in the next room when the widow admits her stealthy visitor but the voice sounds familiar to Gabriel. He senses that the visit is not a welcome one to the widow, and so he finally rushes in on the stranger, who immediately makes a withdrawal. With all his serious suspicions in mind against this stranger, the locksmith wants to follow the culprit but is held back by Mrs. Rudge, who beseeches him not to pick up a fight with that man because he ”’[…]carries other lives beside his own.’”

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Mrs. Rudge is described in this chapter as a woman in her forties, care-worn but still healthy. However, there always seem to be the traces of a look of ultimate terror on her face, nowhere in particular but still undeniably there. It is when she is in the presence of the sinister stranger that these forebodings (or remnants) of terror are clearly expressed in her features. We also learn that Barnaby was born on the very day of the murder of Mr. Reuben Haredale, and that ”he bore upon his wrist what seemed a smear of blood but half washed out.” What could all this mean?

There also was another detail that I could not quite work out and would like your opinion about: Apparently, Gabriel knows and favours the suit of Miss Emma undertaken by young Chester. The locksmith even sneaks upon a masquerade in order to notify Miss Emma of what has happened to her sweetheart, and we must presume that this happens without the knowledge, and probably approval of Mr. Haredale, because otherwise he would have announced himself properly at the masque and broke his news to both uncle and niece. Now, what should I think of a man who furthers a love affair between two young people behind their elders’ backs, and this a man who has a daughter himself? What is his notion of dealing above-board in such cases? And why does he meddle with other people’s affairs at all?

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Mrs. Rudge is described in this chapter as a woman in her forties, care-worn but still healthy. However, there always seem to be the traces of a look of ultimate terror on her face, nowhere in particular but still undeniably there. It is when she is in the presence of the sinister stranger that these forebodings (or remnants) of terror are clearly expressed in her features. We also learn that Barnaby was born on the very day of the murder of Mr. Reuben Haredale, and that ”he bore upon his wrist what seemed a smear of blood but half washed out.” What could all this mean?

There also was another detail that I could not quite work out and would like your opinion about: Apparently, Gabriel knows and favours the suit of Miss Emma undertaken by young Chester. The locksmith even sneaks upon a masquerade in order to notify Miss Emma of what has happened to her sweetheart, and we must presume that this happens without the knowledge, and probably approval of Mr. Haredale, because otherwise he would have announced himself properly at the masque and broke his news to both uncle and niece. Now, what should I think of a man who furthers a love affair between two young people behind their elders’ backs, and this a man who has a daughter himself? What is his notion of dealing above-board in such cases? And why does he meddle with other people’s affairs at all?

By the way, if you don't find me very active right now, this is due to some sort of typewriter's cramp I've got in my right hand. It started on Wednesday and is still with me. Luckily, I had all the chapter introductions written ...

Tristram wrote: "Is it not strange that all the people in this novel somehow seem to know each other?"

Tristram wrote: "Is it not strange that all the people in this novel somehow seem to know each other?"Yes, it is!

Tristram wrote: "It is obviously on account of Joe Willet that Simon’s readiness to grind and grind has been kindled, and while he is sure that ”’[s]omething will come of this’”, he hopes ”’it mayn’t be human gore!’”

Tristram wrote: "It is obviously on account of Joe Willet that Simon’s readiness to grind and grind has been kindled, and while he is sure that ”’[s]omething will come of this’”, he hopes ”’it mayn’t be human gore!’”I don't know if this was supposed to make me laugh, but it did. Sim is so obviously above his head in both the desires he can't realize and the revenge he hopes to take--it seemed like such a fantasy overstatement on his part. On the other hand, since we're looking forward to a riot, maybe it's not supposed to be funny because what happens when the unreasonably dissatisfied Sims of the world take to the streets in mass?

This opening section did make me laugh repeatedly though, and most of all in Chapter 1 when John Willet is waxing philosophical on "Natur," culminating in working his way around to a loyalist accounting for the Princes of England via a discussion of mermaids--all of it so masterful it had me in tears.

Also I love this line from the description of the Maypole: "the Maypole was an old building, with more gable ends than a lazy man would care to count on a sunny day."

I'm going to do my best with Barnaby Rudge, but I must admit I've never heard anything in a positive light about this novel. Perhaps that is the case because it pales next to A Tale of Two Cities? In my classes about Dickens, I don't recall the teachers uttering a single word about this novel. I'll have to find out for myself.

I'm going to do my best with Barnaby Rudge, but I must admit I've never heard anything in a positive light about this novel. Perhaps that is the case because it pales next to A Tale of Two Cities? In my classes about Dickens, I don't recall the teachers uttering a single word about this novel. I'll have to find out for myself.

John wrote: "I'm going to do my best with Barnaby Rudge, but I must admit I've never heard anything in a positive light about this novel. Perhaps that is the case because it pales next to A Tale of Two Cities? ..."

Hi John

BR is not one of the most widely read or praised novels of Dickens. Candidly, it is not a favourite of mine. Nevertheless, within its pages is much to enjoy. Also, I feel in it a distinct corner being turned from the “early” Dickens to the much more mature Dickens where we find much tighter plots, a more sustained thematic focus, and depth of characterization.

BR gives us the wonderful Dolly Varden, a curious collection of father-son relationships, and, as Julie notes above, great moments of humour. BR is, as you note, one of two historical novels Dickens wrote. It’s interesting to compare his historical novels to his other fiction. I’m sure the Curiosities will have lots to talk about, discuss and wonder about.

Hi John

BR is not one of the most widely read or praised novels of Dickens. Candidly, it is not a favourite of mine. Nevertheless, within its pages is much to enjoy. Also, I feel in it a distinct corner being turned from the “early” Dickens to the much more mature Dickens where we find much tighter plots, a more sustained thematic focus, and depth of characterization.

BR gives us the wonderful Dolly Varden, a curious collection of father-son relationships, and, as Julie notes above, great moments of humour. BR is, as you note, one of two historical novels Dickens wrote. It’s interesting to compare his historical novels to his other fiction. I’m sure the Curiosities will have lots to talk about, discuss and wonder about.

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "I'm going to do my best with Barnaby Rudge, but I must admit I've never heard anything in a positive light about this novel. Perhaps that is the case because it pales next to A Tale of..."

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "I'm going to do my best with Barnaby Rudge, but I must admit I've never heard anything in a positive light about this novel. Perhaps that is the case because it pales next to A Tale of..."Thanks Peter. I've never read A Tale of Two Cities, so perhaps coming in as a clean slate to BR and then A Tale of Two Cities will be enlightening for me. I find it interesting that Dickens today is really two Dickens: the canonical novels (as the professors and critics term them) and the works that go unmentioned. I won't say forgotten, just unmentioned.

I'm sad to report that I'm behind on my reading, and have only gotten through chapter two, so I'm not reading comments yet - only Tristram's first couple of chapter summaries.

I'm sad to report that I'm behind on my reading, and have only gotten through chapter two, so I'm not reading comments yet - only Tristram's first couple of chapter summaries. But only two chapters in, I'm already enjoying this novel. The story of Haredale's mysterious death actually seems like it's going to be integral to the plot (unlike the tales in Pickwick, for example). In fact, it's easy to jump to certain conclusions about the stranger's identity, but I'll keep my speculation to myself for now. And I love the description of the Maypole. (by the way...shall we be vacating the Jolly Sandboys soon, in order to enjoy John Willet's hospitality?)

But the reason I wanted to check in before reading the entire week's selection was to gush over one of the passages in chapter two that I just loved. Sure enough, Tristram is one - or a dozen - steps ahead of me and has already quoted the description of Gabriel Varden, and how Father Time treats some of his children. Just wonderful.

Off to chapter 3, and back to the Maypole!

I liked the description of the Maypole too, and John Willet's speech about "Natur" and the gift of "argeyment." So funny. His buddies seem to represent a group mind. Where he looks, they look, all in unison.

I liked the description of the Maypole too, and John Willet's speech about "Natur" and the gift of "argeyment." So funny. His buddies seem to represent a group mind. Where he looks, they look, all in unison.

Alissa wrote: "I liked the description of the Maypole too, and John Willet's speech about "Natur" and the gift of "argeyment." So funny. His buddies seem to represent a group mind. Where he looks, they look, all ..."

Alissa wrote: "I liked the description of the Maypole too, and John Willet's speech about "Natur" and the gift of "argeyment." So funny. His buddies seem to represent a group mind. Where he looks, they look, all ..."Yes, and also the description of Gabriel Varden's approach to London is wonderful--although this is also so odd because Gabriel sleeps through it. Whose head are we in???

Tristram wrote: "When Gabriel is approaching London, we get a vivid description of the town awaiting him in the darkness, and this description ends with the words ”[…] and London—visible in the darkness by its own faint light, and not by that of Heaven—was at hand”. What does this ominous comment on the narrator’s part imply? Is London, as opposed to the rural outskirts, a place that is shunned by Divine light, a place of man-made destiny?..."

Tristram wrote: "When Gabriel is approaching London, we get a vivid description of the town awaiting him in the darkness, and this description ends with the words ”[…] and London—visible in the darkness by its own faint light, and not by that of Heaven—was at hand”. What does this ominous comment on the narrator’s part imply? Is London, as opposed to the rural outskirts, a place that is shunned by Divine light, a place of man-made destiny?..."I suppose I've read enough Dickens that I should realize that his descriptions often do have some implications. But as I read this, I took it quite literally - that the lights of the city (were gas lights in use at that time?) were guiding Varden's way in the dark of night moreso than the sun, the moon, or the stars.

I've just looked it up, and gaslights were first used commercially in the 1790s, so I guess at the time of the Gordon Riots London was lit at night by torches and candles. Would there have been "streetlights"? Unattended fire seems risky and unlikely, but maybe that's my 21st century mindset talking. As Dickens says himself in this chapter, that part of London wasn't the metropolis it became in his time, and certainly not what it is today! Would candles and torch light have been enough to be a beacon for travelers?

In thinking about this, I'm reminded of the star of Bethlehem. Perhaps Tristram is right, that Dickens is alluding to the notion that we won't find anything holy in this city.

Interesting notes, Tristram, thank you. My interest has been piqued in this first section and am finding these characters very intriguing. I see that the chapters are short enough that I believe I will be able to keep up and still get some other things read at the same time. I know nothing of the Gordon Riots so it should be interesting to learn something of them. Historical novels are my favorites but of course all of Dickens seems historical to me since it is all written and takes place in the past. But having this based on real historical events makes it all the more interesting.

Interesting notes, Tristram, thank you. My interest has been piqued in this first section and am finding these characters very intriguing. I see that the chapters are short enough that I believe I will be able to keep up and still get some other things read at the same time. I know nothing of the Gordon Riots so it should be interesting to learn something of them. Historical novels are my favorites but of course all of Dickens seems historical to me since it is all written and takes place in the past. But having this based on real historical events makes it all the more interesting.

MaryLou asked where we were going to meet now we are leaving TOCS. Tristram is our expert on pub locations and I am certain he will very soon announce where our next local will be.

As to the Maypole, however, it is a great place to think about. There is much about it we can reflect upon. First, as mentioned, it appears that it will be a central location in this novel. Buildings often become characters ( well, character-like) in Dickens novels. Their descriptions will often lead us to a better understanding of other characters, advancement of plot, and even themes. I think we should pay close attention to the Maypole.

Isn’t Simon Tappertit an interesting character? I’m not sure what to make of him yet, but he is quirky, mysterious, and a bit annoying. With those ingredients Dickens can certainly brew up lots of possibilities.

There is also love in the air, and knowing Dickens, there are twists and turns before we are finished with the novel.

So far, my favourite character is Varden, the locksmith. I like his grounded nature, and he seems like a good person to share a pint with at the Maypole.

And back to the Maypole for a moment. Who really are all the people in the Maypole, both the regulars and the more mysterious people in the shadows, and how will they fit into the novel as we proceed?

As to the Maypole, however, it is a great place to think about. There is much about it we can reflect upon. First, as mentioned, it appears that it will be a central location in this novel. Buildings often become characters ( well, character-like) in Dickens novels. Their descriptions will often lead us to a better understanding of other characters, advancement of plot, and even themes. I think we should pay close attention to the Maypole.

Isn’t Simon Tappertit an interesting character? I’m not sure what to make of him yet, but he is quirky, mysterious, and a bit annoying. With those ingredients Dickens can certainly brew up lots of possibilities.

There is also love in the air, and knowing Dickens, there are twists and turns before we are finished with the novel.

So far, my favourite character is Varden, the locksmith. I like his grounded nature, and he seems like a good person to share a pint with at the Maypole.

And back to the Maypole for a moment. Who really are all the people in the Maypole, both the regulars and the more mysterious people in the shadows, and how will they fit into the novel as we proceed?

Tristram wrote: "By the way, if you don't find me very active right now, this is due to some sort of typewriter's cramp I've got in my right hand. It started on Wednesday and is still with me. Luckily, I had all th..."

You mean there could have been more school like questions? What a thought. :-)

You mean there could have been more school like questions? What a thought. :-)

Tristram wrote: "Dolly Varden is Gabriel’s daughter (and probably one of the finest characters in the novel, but that’s just me talking)."

Dolly Varden is one if the finest characters in the novel? No she's not. Oh, I just read the but that's just me talking part of the sentence, that explains it.

Dolly Varden is one if the finest characters in the novel? No she's not. Oh, I just read the but that's just me talking part of the sentence, that explains it.

I thought while I was reading these chapters that Dickens's sympathies are not with the young against the old, sympathizing with Joe in his relationship with his father, because in the next relationship we have the Gabriel Varden - Sim Tappertit relationship which begins two chapters later, and here the elder is benevolent and Sim is a believer in his own delusions of grandeur, at least that's how I see it.

I also made a note in Chapter 3 when Gabriel, trying to keep the peace between Joe and his father tells Joe to "bear with his father’s caprices, and rather endeavour to turn them aside by temperate remonstrance than by ill-timed rebellion", could come to mean more than a rebellion of a son from his father.

And I find it interesting that originally Dickens signed a contract in 1836 to write the book, then titled "Gabriel Varden-The Locksmith of London", for Richard Bentley of Bentley's Miscellany, he eventually changed publishers and the book didn't get published until later, with many changes. You should soon hate Gabriel Tristram, he's too nice.

I also made a note in Chapter 3 when Gabriel, trying to keep the peace between Joe and his father tells Joe to "bear with his father’s caprices, and rather endeavour to turn them aside by temperate remonstrance than by ill-timed rebellion", could come to mean more than a rebellion of a son from his father.

And I find it interesting that originally Dickens signed a contract in 1836 to write the book, then titled "Gabriel Varden-The Locksmith of London", for Richard Bentley of Bentley's Miscellany, he eventually changed publishers and the book didn't get published until later, with many changes. You should soon hate Gabriel Tristram, he's too nice.

Here is my favorite part of Chapter 4 where we have Sim who seems to think he can win any beauty just by the way he looks at her:

"Although Sim Tappertit had taken no share in this conversation, no part of it being addressed to him, he had not been wanting in such silent manifestations of astonishment, as he deemed most compatible with the favourable display of his eyes. Regarding the pause which now ensued, as a particularly advantageous opportunity for doing great execution with them upon the locksmith's daughter (who he had no doubt was looking at him in mute admiration), he began to screw and twist his face, and especially those features, into such extraordinary, hideous, and unparalleled contortions, that Gabriel, who happened to look towards him, was stricken with amazement.

'Why, what the devil's the matter with the lad?' cried the locksmith. 'Is he choking?'

'Who?' demanded Sim, with some disdain.

'Who? Why, you,' returned his master. 'What do you mean by making those horrible faces over your breakfast?'

'Faces are matters of taste, sir,' said Mr Tappertit, rather discomfited; not the less so because he saw the locksmith's daughter smiling.

"Although Sim Tappertit had taken no share in this conversation, no part of it being addressed to him, he had not been wanting in such silent manifestations of astonishment, as he deemed most compatible with the favourable display of his eyes. Regarding the pause which now ensued, as a particularly advantageous opportunity for doing great execution with them upon the locksmith's daughter (who he had no doubt was looking at him in mute admiration), he began to screw and twist his face, and especially those features, into such extraordinary, hideous, and unparalleled contortions, that Gabriel, who happened to look towards him, was stricken with amazement.

'Why, what the devil's the matter with the lad?' cried the locksmith. 'Is he choking?'

'Who?' demanded Sim, with some disdain.

'Who? Why, you,' returned his master. 'What do you mean by making those horrible faces over your breakfast?'

'Faces are matters of taste, sir,' said Mr Tappertit, rather discomfited; not the less so because he saw the locksmith's daughter smiling.

The locksmith was upon him—had the skirts of his streaming garment almost in his grasp—when his arms were tightly clutched, and the widow flung herself upon the ground before him.

‘The other way—the other way,’ she cried. ‘He went the other way. Turn—turn!’

‘The other way! I see him now,’ rejoined the locksmith, pointing—‘yonder—there—there is his shadow passing by that light. What—who is this? Let me go.’

‘Come back, come back!’ exclaimed the woman, clasping him; ‘Do not touch him on your life. I charge you, come back. He carries other lives besides his own. Come back!’

‘What does this mean?’ cried the locksmith.

‘No matter what it means, don’t ask, don’t speak, don’t think about it. He is not to be followed, checked, or stopped. Come back!’

The old man looked at her in wonder, as she writhed and clung about him; and, borne down by her passion, suffered her to drag him into the house. It was not until she had chained and double-locked the door, fastened every bolt and bar with the heat and fury of a maniac, and drawn him back into the room, that she turned upon him, once again, that stony look of horror, and, sinking down into a chair, covered her face, and shuddered, as though the hand of death were on her.

I can think of no reason this mysterious person would show up at the house of Mrs. Rudge, and especially why she would fight so hard to prevent Gabriel from following him. Mysterious men bring the stranger at the Maypole to mind, and I'm wondering if this is the same man, and if this mysterious person is also the man who attacked Edward Chester. After all, he did follow him out of the Maypole.

‘The other way—the other way,’ she cried. ‘He went the other way. Turn—turn!’

‘The other way! I see him now,’ rejoined the locksmith, pointing—‘yonder—there—there is his shadow passing by that light. What—who is this? Let me go.’

‘Come back, come back!’ exclaimed the woman, clasping him; ‘Do not touch him on your life. I charge you, come back. He carries other lives besides his own. Come back!’

‘What does this mean?’ cried the locksmith.

‘No matter what it means, don’t ask, don’t speak, don’t think about it. He is not to be followed, checked, or stopped. Come back!’

The old man looked at her in wonder, as she writhed and clung about him; and, borne down by her passion, suffered her to drag him into the house. It was not until she had chained and double-locked the door, fastened every bolt and bar with the heat and fury of a maniac, and drawn him back into the room, that she turned upon him, once again, that stony look of horror, and, sinking down into a chair, covered her face, and shuddered, as though the hand of death were on her.

I can think of no reason this mysterious person would show up at the house of Mrs. Rudge, and especially why she would fight so hard to prevent Gabriel from following him. Mysterious men bring the stranger at the Maypole to mind, and I'm wondering if this is the same man, and if this mysterious person is also the man who attacked Edward Chester. After all, he did follow him out of the Maypole.

Tristram wrote: "Our final chapter for this week reintroduces the mysterious stranger we have followed in Chapters 1-3. In the evening, Gabriel pays a visit to Mrs. Rudge in order to learn how the patient is faring..."

Tristram

Your question as to why Varden would support the the love affair “between two young people behind their elders’ backs” even though he has a daughter I think resides in his own marriage. Mrs Varden is portrayed as a shrew. She has no patience for her husband, is overly emotional, and seems to thrive on making others miserable.

I think Varden is aware of how attractive his daughter is but has the sense to realize that his interference in any of Dolly’s gentleman callers could nudge her towards that man. Best to let her heart find its mate. As to why he would have married his wife we may have to wait for that information to be supplied in a future chapter.

Tristram

Your question as to why Varden would support the the love affair “between two young people behind their elders’ backs” even though he has a daughter I think resides in his own marriage. Mrs Varden is portrayed as a shrew. She has no patience for her husband, is overly emotional, and seems to thrive on making others miserable.

I think Varden is aware of how attractive his daughter is but has the sense to realize that his interference in any of Dolly’s gentleman callers could nudge her towards that man. Best to let her heart find its mate. As to why he would have married his wife we may have to wait for that information to be supplied in a future chapter.

Kim, I did get the impression that the mysterious stranger from The Maypole and the one who attacked Edward Chester and the one now showing up at the Rudge house are all one and the same. I'm not sure that it actually says that or just gives that impression. Can someone clear that up? Tristram?

Kim, I did get the impression that the mysterious stranger from The Maypole and the one who attacked Edward Chester and the one now showing up at the Rudge house are all one and the same. I'm not sure that it actually says that or just gives that impression. Can someone clear that up? Tristram?

I hate computers. I hate anything you plug in. I had them all ready, all the illustrations, all the texts, all the commentaries, I was at this all afternoon, I was within seconds, actual seconds of starting to post, and there was a click and the computer once again died and with it my illustrations. If the computer decides to cooperate hopefully tomorrow things will go faster than they did today, now I know where to go to get them, if it doesn't want to cooperate it may be awhile, I don't know how to post illustrations from this device - yet. In case I didn't say it loud enough, I really hate computers.

Bobbie wrote: "Kim, I did get the impression that the mysterious stranger from The Maypole and the one who attacked Edward Chester and the one now showing up at the Rudge house are all one and the same. I'm not s..."

Ah, Bobbie

You may well be onto something. :-).

There are definitely links among the places you mentioned and the mysterious stranger. Being Dickens and a Victorian novel, we will have to wait a bit longer for any confirmation of who he is and how he fits into the narrative. Dickens loved to create suspense, and one reason why was because with the serial publication of his novels he could keep his readers hanging on for the next instalment.

This coming weekend my commentary will pick up the thread of the mysterious gentleman. Sooner or later the Dickens reveal will occur.

Ah, Bobbie

You may well be onto something. :-).

There are definitely links among the places you mentioned and the mysterious stranger. Being Dickens and a Victorian novel, we will have to wait a bit longer for any confirmation of who he is and how he fits into the narrative. Dickens loved to create suspense, and one reason why was because with the serial publication of his novels he could keep his readers hanging on for the next instalment.

This coming weekend my commentary will pick up the thread of the mysterious gentleman. Sooner or later the Dickens reveal will occur.

Kim wrote: "I hate computers. I hate anything you plug in. I had them all ready, all the illustrations, all the texts, all the commentaries, I was at this all afternoon, I was within seconds, actual seconds of..."

Kim

I hear you loud and clear. I too hold my breath the moment before I post my commentaries. Sadly, I can offer only support, not any suggestions of what to do.

Kim

I hear you loud and clear. I too hold my breath the moment before I post my commentaries. Sadly, I can offer only support, not any suggestions of what to do.

Kim wrote: "I hate computers. I hate anything you plug in. I had them all ready, all the illustrations, all the texts, all the commentaries, I was at this all afternoon, I was within seconds, actual seconds of..."

Kim wrote: "I hate computers. I hate anything you plug in. I had them all ready, all the illustrations, all the texts, all the commentaries, I was at this all afternoon, I was within seconds, actual seconds of..."Computers are the bane. I still like my old desktop where I can write and type like I did on an old Underwood. But having recently gotten acquainted with an Apple iPad, I'm learning to type and post on a device that measures 10 inches. I'm not sure I'll ever warm up to that. I feel like I need fingers of Lilliputians and the patience of Thomas Edison.

Tristram, I hope your hand is better soon. I can't imagine reading this novel without the benefit of your observations. (Wow - that's a selfish response! I also wouldn't want you to be incapacitated or in pain!)

Tristram, I hope your hand is better soon. I can't imagine reading this novel without the benefit of your observations. (Wow - that's a selfish response! I also wouldn't want you to be incapacitated or in pain!) Tristram wrote: "...Simon Tappertit, whose many quirks and peculiarities mark him as a comic relief figure..."

Comic relief? That's not what I got at all! In fact, I found Sim rather sinister. Not evil, perhaps, but a troublemaker. He reminded me a bit of Orlick in Great Expectations or Uriah Heep in David Copperfield -- he seems like a schemer with a chip on his shoulder. I'll keep an eye on him. Smallweed, in Bleak House was a horrible person, but I considered him comic relief ("shake me up, Judy!") so maybe I'll come to find Sim entertaining, too.

Tristram wrote: And why does he [Gabriel] meddle with other people’s affairs at all?

I defer to Mrs. Rudge in this matter, who says of Gabriel:

‘Your kind heart has brought you here again. Nothing will keep you at home, I know of old, if there are friends to serve or comfort, out of doors.’

I think he was just being thoughtful and didn't want Emma (this novel's Mary Hogarth, perhaps?) to hear of Edward's attack through the grapevine, with exaggerated accounts of his condition. That's not quite the same as playing matchmaker behind her uncle's back.

Kim - Gabriel DID identify the mysterious stranger at the Rudge house as the gentleman he'd encountered on the road. I think it's safe to assume that he is the common denominator in all that's happened in the novel so far. Also, I like your observation that Gabriel's admonition to young Joe to endeavour to turn them aside by temperate remonstrance than by ill-timed rebellion is foreshadowing and will serve as good advice in the bigger rebellion to come.

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim.... Also, I like your observation that Gabriel's admonition to young Joe to endeavour to turn them aside by temperate remonstrance than by ill-timed rebellion is foreshadowing and will serve as good advice in the bigger rebellion to come. .."

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim.... Also, I like your observation that Gabriel's admonition to young Joe to endeavour to turn them aside by temperate remonstrance than by ill-timed rebellion is foreshadowing and will serve as good advice in the bigger rebellion to come. .."I like that, too.

Also I like Joe, who is both patient and self-assertive. Though it does look like the proportions of these two qualities may be likely to change soon.

Well, let's see what happens:

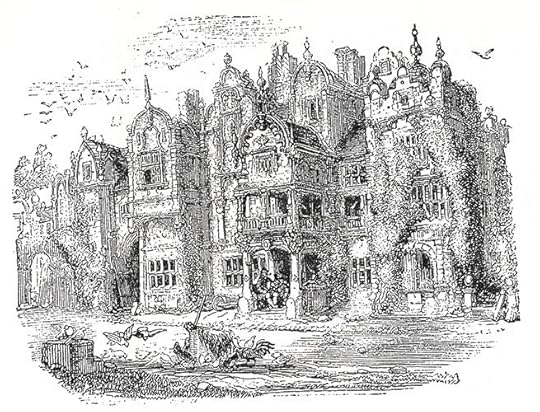

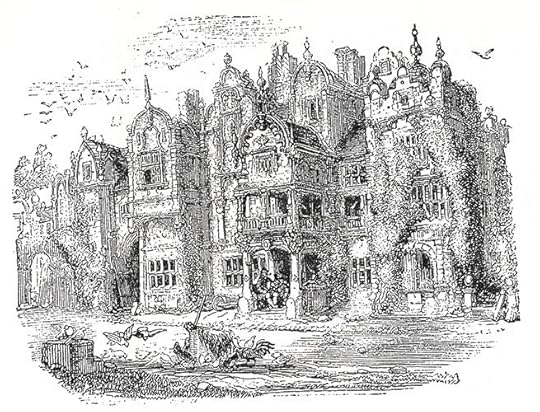

The Maypole

Chapter 1

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

The Maypole—by which term from henceforth is meant the house, and not its sign—the Maypole was an old building, with more gable ends than a lazy man would care to count on a sunny day; huge zig-zag chimneys, out of which it seemed as though even smoke could not choose but come in more than naturally fantastic shapes, imparted to it in its tortuous progress; and vast stables, gloomy, ruinous, and empty. The place was said to have been built in the days of King Henry the Eighth; and there was a legend, not only that Queen Elizabeth had slept there one night while upon a hunting excursion, to wit, in a certain oak-panelled room with a deep bay window, but that next morning, while standing on a mounting block before the door with one foot in the stirrup, the virgin monarch had then and there boxed and cuffed an unlucky page for some neglect of duty. The matter-of-fact and doubtful folks, of whom there were a few among the Maypole customers, as unluckily there always are in every little community, were inclined to look upon this tradition as rather apocryphal; but, whenever the landlord of that ancient hostelry appealed to the mounting block itself as evidence, and triumphantly pointed out that there it stood in the same place to that very day, the doubters never failed to be put down by a large majority, and all true believers exulted as in a victory.

Whether these, and many other stories of the like nature, were true or untrue, the Maypole was really an old house, a very old house, perhaps as old as it claimed to be, and perhaps older, which will sometimes happen with houses of an uncertain, as with ladies of a certain, age. Its windows were old diamond-pane lattices, its floors were sunken and uneven, its ceilings blackened by the hand of time, and heavy with massive beams. Over the doorway was an ancient porch, quaintly and grotesquely carved; and here on summer evenings the more favoured customers smoked and drank—ay, and sang many a good song too, sometimes—reposing on two grim-looking high-backed settles, which, like the twin dragons of some fairy tale, guarded the entrance to the mansion.

In the chimneys of the disused rooms, swallows had built their nests for many a long year, and from earliest spring to latest autumn whole colonies of sparrows chirped and twittered in the eaves. There were more pigeons about the dreary stable-yard and out-buildings than anybody but the landlord could reckon up. The wheeling and circling flights of runts, fantails, tumblers, and pouters, were perhaps not quite consistent with the grave and sober character of the building, but the monotonous cooing, which never ceased to be raised by some among them all day long, suited it exactly, and seemed to lull it to rest. With its overhanging stories, drowsy little panes of glass, and front bulging out and projecting over the pathway, the old house looked as if it were nodding in its sleep. Indeed, it needed no very great stretch of fancy to detect in it other resemblances to humanity. The bricks of which it was built had originally been a deep dark red, but had grown yellow and discoloured like an old man’s skin; the sturdy timbers had decayed like teeth; and here and there the ivy, like a warm garment to comfort it in its age, wrapt its green leaves closely round the time-worn walls.

It was a hale and hearty age though, still: and in the summer or autumn evenings, when the glow of the setting sun fell upon the oak and chestnut trees of the adjacent forest, the old house, partaking of its lustre, seemed their fit companion, and to have many good years of life in him yet.

Commentary:

Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge, which appeared in Dickens weekly Master Humphrey's Clock from February 1841 to November 1841, were engraved in wood and dropped into the text. Hablot Browne (Phiz) and George Cattermole provided the 76 illustrations (most for any Dickens novel) with Browne supplying 61 and Cattermole 15. As with The Old Curiosity Shop Browne did most of the character sketches with Cattermole supplying the architectural interiors and exteriors. The woodcuts were engraved by Landells, Gray, Williams, and Vasey.

The Maypole

Chapter 1

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

The Maypole—by which term from henceforth is meant the house, and not its sign—the Maypole was an old building, with more gable ends than a lazy man would care to count on a sunny day; huge zig-zag chimneys, out of which it seemed as though even smoke could not choose but come in more than naturally fantastic shapes, imparted to it in its tortuous progress; and vast stables, gloomy, ruinous, and empty. The place was said to have been built in the days of King Henry the Eighth; and there was a legend, not only that Queen Elizabeth had slept there one night while upon a hunting excursion, to wit, in a certain oak-panelled room with a deep bay window, but that next morning, while standing on a mounting block before the door with one foot in the stirrup, the virgin monarch had then and there boxed and cuffed an unlucky page for some neglect of duty. The matter-of-fact and doubtful folks, of whom there were a few among the Maypole customers, as unluckily there always are in every little community, were inclined to look upon this tradition as rather apocryphal; but, whenever the landlord of that ancient hostelry appealed to the mounting block itself as evidence, and triumphantly pointed out that there it stood in the same place to that very day, the doubters never failed to be put down by a large majority, and all true believers exulted as in a victory.

Whether these, and many other stories of the like nature, were true or untrue, the Maypole was really an old house, a very old house, perhaps as old as it claimed to be, and perhaps older, which will sometimes happen with houses of an uncertain, as with ladies of a certain, age. Its windows were old diamond-pane lattices, its floors were sunken and uneven, its ceilings blackened by the hand of time, and heavy with massive beams. Over the doorway was an ancient porch, quaintly and grotesquely carved; and here on summer evenings the more favoured customers smoked and drank—ay, and sang many a good song too, sometimes—reposing on two grim-looking high-backed settles, which, like the twin dragons of some fairy tale, guarded the entrance to the mansion.

In the chimneys of the disused rooms, swallows had built their nests for many a long year, and from earliest spring to latest autumn whole colonies of sparrows chirped and twittered in the eaves. There were more pigeons about the dreary stable-yard and out-buildings than anybody but the landlord could reckon up. The wheeling and circling flights of runts, fantails, tumblers, and pouters, were perhaps not quite consistent with the grave and sober character of the building, but the monotonous cooing, which never ceased to be raised by some among them all day long, suited it exactly, and seemed to lull it to rest. With its overhanging stories, drowsy little panes of glass, and front bulging out and projecting over the pathway, the old house looked as if it were nodding in its sleep. Indeed, it needed no very great stretch of fancy to detect in it other resemblances to humanity. The bricks of which it was built had originally been a deep dark red, but had grown yellow and discoloured like an old man’s skin; the sturdy timbers had decayed like teeth; and here and there the ivy, like a warm garment to comfort it in its age, wrapt its green leaves closely round the time-worn walls.

It was a hale and hearty age though, still: and in the summer or autumn evenings, when the glow of the setting sun fell upon the oak and chestnut trees of the adjacent forest, the old house, partaking of its lustre, seemed their fit companion, and to have many good years of life in him yet.

Commentary:

Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge, which appeared in Dickens weekly Master Humphrey's Clock from February 1841 to November 1841, were engraved in wood and dropped into the text. Hablot Browne (Phiz) and George Cattermole provided the 76 illustrations (most for any Dickens novel) with Browne supplying 61 and Cattermole 15. As with The Old Curiosity Shop Browne did most of the character sketches with Cattermole supplying the architectural interiors and exteriors. The woodcuts were engraved by Landells, Gray, Williams, and Vasey.

The Unsocialble Stranger

Chapter 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The evening with which we have to do, was neither a summer nor an autumn one, but the twilight of a day in March, when the wind howled dismally among the bare branches of the trees, and rumbling in the wide chimneys and driving the rain against the windows of the Maypole Inn, gave such of its frequenters as chanced to be there at the moment an undeniable reason for prolonging their stay, and caused the landlord to prophesy that the night would certainly clear at eleven o’clock precisely,—which by a remarkable coincidence was the hour at which he always closed his house.

The name of him upon whom the spirit of prophecy thus descended was John Willet, a burly, large-headed man with a fat face, which betokened profound obstinacy and slowness of apprehension, combined with a very strong reliance upon his own merits. It was John Willet’s ordinary boast in his more placid moods that if he were slow he was sure; which assertion could, in one sense at least, be by no means gainsaid, seeing that he was in everything unquestionably the reverse of fast, and withal one of the most dogged and positive fellows in existence—always sure that what he thought or said or did was right, and holding it as a thing quite settled and ordained by the laws of nature and Providence, that anybody who said or did or thought otherwise must be inevitably and of necessity wrong.

Mr Willet walked slowly up to the window, flattened his fat nose against the cold glass, and shading his eyes that his sight might not be affected by the ruddy glow of the fire, looked abroad. Then he walked slowly back to his old seat in the chimney-corner, and, composing himself in it with a slight shiver, such as a man might give way to and so acquire an additional relish for the warm blaze, said, looking round upon his guests:

‘It’ll clear at eleven o’clock. No sooner and no later. Not before and not arterwards.’

‘How do you make out that?’ said a little man in the opposite corner. ‘The moon is past the full, and she rises at nine.’

John looked sedately and solemnly at his questioner until he had brought his mind to bear upon the whole of his observation, and then made answer,

in a tone which seemed to imply that the moon was peculiarly his business and nobody else’s:

‘Never you mind about the moon. Don’t you trouble yourself about her. You let the moon alone, and I’ll let you alone.’

‘No offence I hope?’ said the little man.

Again John waited leisurely until the observation had thoroughly penetrated to his brain, and then replying, ‘No offence as YET,’ applied a light to his pipe and smoked in placid silence; now and then casting a sidelong look at a man wrapped in a loose riding-coat with huge cuffs ornamented with tarnished silver lace and large metal buttons, who sat apart from the regular frequenters of the house, and wearing a hat flapped over his face, which was still further shaded by the hand on which his forehead rested, looked unsociable enough.

There was another guest, who sat, booted and spurred, at some distance from the fire also, and whose thoughts—to judge from his folded arms and knitted brows, and from the untasted liquor before him—were occupied with other matters than the topics under discussion or the persons who discussed them. This was a young man of about eight-and-twenty, rather above the middle height, and though of somewhat slight figure, gracefully and strongly made. He wore his own dark hair, and was accoutred in a riding dress, which together with his large boots (resembling in shape and fashion those worn by our Life Guardsmen at the present day), showed indisputable traces of the bad condition of the roads. But travel-stained though he was, he was well and even richly attired, and without being overdressed looked a gallant gentleman.

Lying upon the table beside him, as he had carelessly thrown them down, were a heavy riding-whip and a slouched hat, the latter worn no doubt as being best suited to the inclemency of the weather. There, too, were a pair of pistols in a holster-case, and a short riding-cloak. Little of his face was visible, except the long dark lashes which concealed his downcast eyes, but an air of careless ease and natural gracefulness of demeanour pervaded the figure, and seemed to comprehend even those slight accessories, which were all handsome, and in good keeping.

Towards this young gentleman the eyes of Mr Willet wandered but once, and then as if in mute inquiry whether he had observed his silent neighbour. It was plain that John and the young gentleman had often met before. Finding that his look was not returned, or indeed observed by the person to whom it was addressed, John gradually concentrated the whole power of his eyes into one focus, and brought it to bear upon the man in the flapped hat, at whom he came to stare in course of time with an intensity so remarkable, that it affected his fireside cronies, who all, as with one accord, took their pipes from their lips, and stared with open mouths at the stranger likewise.

The sturdy landlord had a large pair of dull fish-like eyes, and the little man who had hazarded the remark about the moon (and who was the parish-clerk and bell-ringer of Chigwell, a village hard by) had little round black shiny eyes like beads; moreover this little man wore at the knees of his rusty black breeches, and on his rusty black coat, and all down his long flapped waistcoat, little queer buttons like nothing except his eyes; but so like them, that as they twinkled and glistened in the light of the fire, which shone too in his bright shoe-buckles, he seemed all eyes from head to foot, and to be gazing with every one of them at the unknown customer. No wonder that a man should grow restless under such an inspection as this, to say nothing of the eyes belonging to short Tom Cobb the general chandler and post-office keeper, and long Phil Parkes the ranger, both of whom, infected by the example of their companions, regarded him of the flapped hat no less attentively.

The stranger became restless; perhaps from being exposed to this raking fire of eyes, perhaps from the nature of his previous meditations—most probably from the latter cause, for as he changed his position and looked hastily round, he started to find himself the object of such keen regard, and darted an angry and suspicious glance at the fireside group. It had the effect of immediately diverting all eyes to the chimney, except those of John Willet, who finding himself as it were, caught in the fact, and not being (as has been already observed) of a very ready nature, remained staring at his guest in a particularly awkward and disconcerted manner.

‘Well?’ said the stranger.

Well. There was not much in well. It was not a long speech. ‘I thought you gave an order,’ said the landlord, after a pause of two or three minutes for consideration.

The stranger took off his hat, and disclosed the hard features of a man of sixty or thereabouts, much weatherbeaten and worn by time, and the naturally harsh expression of which was not improved by a dark handkerchief which was bound tightly round his head, and, while it served the purpose of a wig, shaded his forehead, and almost hid his eyebrows. If it were intended to conceal or divert attention from a deep gash, now healed into an ugly seam, which when it was first inflicted must have laid bare his cheekbone, the object was but indifferently attained, for it could scarcely fail to be noted at a glance. His complexion was of a cadaverous hue, and he had a grizzly jagged beard of some three weeks’ date. Such was the figure (very meanly and poorly clad) that now rose from the seat, and stalking across the room sat down in a corner of the chimney, which the politeness or fears of the little clerk very readily assigned to him.

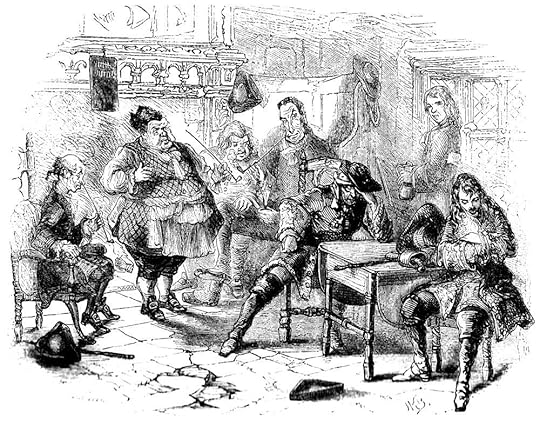

Commentary:

Comparing the plates that appeared in the 1849 edition of Barnaby Rudge to those in a good modern edition, such as the volume in the New Oxford Illustrated Dickens, gives us an idea of how the Victorian reader might have experienced the plates by Phiz — that is, simultaneously with the letterpress illustrated rather than facing such text. In the first place, whereas the illustrations in the New Oxford edition appear on a page 18.3 x 11.5 centimeters, those that Bradbury and Evans published in 1849 appear on a larger page (25 by 16.5 centimeters). The paper on which the original wood-cuts were printed provides a more important difference than their slightly larger page: in the 1849 edition, the plates appear on the same paper as does the text of the novel, and this arrangement permits printing text on the reverse of each illustration. In the New Oxford, the illustrations are free-standing rather than dropped into the text, usually facing the passages realized. In contrast, the original bound volume of 1849 has the plates on much heavier stock; in the 1849 edition the text bleeds through slightly, but in the New Oxford it does not, thus making the plates look somewhat better but also more important. Moreover, the ornamental capital letter vignettes designed by Phiz are not reproduced in modern editions, and pictures that served as head- and tailpieces merely appear on separate pages in the New Oxford. On the whole, the seventy-seven New Oxford Illustrated Dickens plates for Barnaby Rudge are quite clear, but those in the original often seem darker, sharper, and more dramatic, even though the plates are not printed on separate sheets but are integrated into the text, often with the print from the verso showing through.

Originally, when he proposed the novel to publisher Richard Bentley, Dickens had had veteran illustrator George Cruikshank in mind as his sole illustrator for the historical novel. However, when his editorial squabbles with Bentley came to a head, Dickens ceased work on the project, and Cruikshank took the commissions of a number of other authors, so that in January 1841 Dickens, taking up the novel again in earnest, suddenly found himself without Cruikshank. Thus, Dickens chose to revert to Phiz, his partner in The Pickwick Papers, who produced (according to Browne Lester) for the roaring tale fifty-nine illustrations, "mainly of characters, Cattermole producing about nineteen, usually of settings". Browne Lester describes Phiz's specialty at this point as the "low" characters such as Hugh and Sim Tappertit, "active moments, and comic rascality, while Cattermole would embark upon loftier, antiquarian, angelic, and architectural subjects".

John Willet and His Cronies

Chapter 1

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge and Hard Times (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867)

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Willet walked slowly up to the window, flattened his fat nose against the cold glass, and shading his eyes that his sight might not be affected by the ruddy glow of the fire, looked abroad. Then he walked slowly back to his old seat in the chimney-corner, and, composing himself in it with a slight shiver, such as a man might give way to and so acquire an additional relish for the warm blaze, said, looking round upon his guests, —

"It'll clear at eleven o'clock. No sooner and no later. Not before and not arterwards."

"How do you make out that?" said a little man in the opposite corner. "The moon is past the full, and she rises at nine."

John looked sedately and solemnly at his questioner until he had brought his mind to bear upon the whole of his observation, and then made answer, in a tone which seemed to imply that the moon was peculiarly his business and nobody else's, —

"Never you mind about the moon. Don't you trouble yourself about her. You let the moon alone, and I'll let you alone."

"No offence I hope?" said the little man.

Soloman Daisy tells his story

Chapter 1

Dudley Tennant

From Barnaby Rudge: Told to Children, by Ethel Lindsay. S.W. Partridge & Co., [1921]

Text Illustrated:

‘That,’ returned the landlord, a little brought down from his dignity by the stranger’s surliness, ‘is a Maypole story, and has been any time these four-and-twenty years. That story is Solomon Daisy’s story. It belongs to the house; and nobody but Solomon Daisy has ever told it under this roof, or ever shall—that’s more.’

The man glanced at the parish-clerk, whose air of consciousness and importance plainly betokened him to be the person referred to, and, observing that he had taken his pipe from his lips, after a very long whiff to keep it alight, and was evidently about to tell his story without further solicitation, gathered his large coat about him, and shrinking further back was almost lost in the gloom of the spacious chimney-corner, except when the flame, struggling from under a great faggot, whose weight almost crushed it for the time, shot upward with a strong and sudden glare, and illumining his figure for a moment, seemed afterwards to cast it into deeper obscurity than before.