The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Lazy Tour of Two Idle ...

>

The Lazy Tour ... Chapters 4-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter Five

In this chapter we move from a gothic tale of ghosts, murder, a hanging, and an unquiet night spent in a hotel to a much more lively, busy, and crowded world which is race week at Doncaster. To get there we travel by train with our idle apprentices into “the manufacturing bosom of Yorkshire” and experience the singing of “hundreds of third class excursionists.” I was fascinated by the train trip. First, it gives us a feeling of train travel in the 19C. The days of the Pickwickian coach ride are gone and is here replaced with masses of people. In NN we travelled north to Dotheboys Hall with Nicholas on a very cold and uncomfortable coach. In TLT we travel to Yorkshire and its “dreary and quenched panorama” on a train. Modes of transportation have changed. With the exception of DS, there are few sustained descriptions of t(e impact of trains in the novels of Dickens.

Doncaster is brimming with betting people “from peers to paupers, betting incessantly.” The racing week has created “impassable” crowds and the “roar and uproar” of people who are drinking, singing, and gambling. The pace, tone, and transition from chapter four to to chapter five is remarkable. Gamblers and drinkers are everywhere in this chapter. I think Dickens’s mention of Spurgeon might be an example of how modern readers may miss a Victorian reference that would be understood by the original readers of TLT. Charles Haddon Spurgeon was an evangelical Baptist preacher and, by 1857, the greatest of the preachers in London. He attracted crowds by the thousands to his sermons each week. The great cacophony of Doncaster, the betting on the races, and the drinking in the streets was a world that Spurgeon would have gleefully preached against, and the readers of TLT must have immensely enjoyed imagining such an occurrence happening.

While Idle is content to rest and observe the crowds from his hotel room, Goodchild heads out into the crowds and revels in the energy of the streets. I find this a strange way to enjoy being idle. What we learn, however, is that Goodchild (aka Dickens) had “fallen into a dreadful state concerning a pair of little lilac gloves and a little bonnet.” Idle comments how Goodchild was “lunatically seized” and that the women in the little bonnet “with her golden hair” was like glorious sunlight. This mystery woman is never given a name in chapter five. Indeed, she is referred to only as the “dear unknown wearer with the golden hair.” Now, taken on one level, this is a rather innocent and unimportant bit of writing suggesting little more than there areDoncaster attractive young ladies who enjoy the races. On another level, however, we have a more intimate and personal analysis. There is much speculation that this encounter between Goodchild and the young lady is, in fact, a reference to Dickens meeting up with Ellen Ternan. Ellen did have blond hair, was at Doncaster during the time Dickens and Collins were there, and is again slyly mentioned in some of Dickens correspondence. Shortly after Dickens returned to London from Doncaster he had a doorway covered and thus established a separate bedroom from his wife Catherine. Oh, to be a fly on the wall when Dickens and Collins talked about their time in Doncaster.

Thoughts

There is a clear change in tone between the gothic ghost tale of the previous chapter to the cacophony of chapter five. What do you think the reasons might be for this shift in tone and style?

Are you becoming weary of the format of the twin author narratives or do you enjoy this style? Why?

From your reading of the story who do you find to be the dominant author? What leads you to this decision?

In this chapter we see another instance where there may be two levels of interpreting the plot. To what extent do you think it possible that the sub-text is a story of Dickens and Ellen Ternan meeting in Doncaster?

Do you think the reference to Spurgeon was meant to be humourous, sarcastic or unintentional given the circumstances occurring in Doncaster?

To me, the ending of this story was very abrupt. What is your opinion of the ending?

What is your opinion of the complete travelogue?

In this chapter we move from a gothic tale of ghosts, murder, a hanging, and an unquiet night spent in a hotel to a much more lively, busy, and crowded world which is race week at Doncaster. To get there we travel by train with our idle apprentices into “the manufacturing bosom of Yorkshire” and experience the singing of “hundreds of third class excursionists.” I was fascinated by the train trip. First, it gives us a feeling of train travel in the 19C. The days of the Pickwickian coach ride are gone and is here replaced with masses of people. In NN we travelled north to Dotheboys Hall with Nicholas on a very cold and uncomfortable coach. In TLT we travel to Yorkshire and its “dreary and quenched panorama” on a train. Modes of transportation have changed. With the exception of DS, there are few sustained descriptions of t(e impact of trains in the novels of Dickens.

Doncaster is brimming with betting people “from peers to paupers, betting incessantly.” The racing week has created “impassable” crowds and the “roar and uproar” of people who are drinking, singing, and gambling. The pace, tone, and transition from chapter four to to chapter five is remarkable. Gamblers and drinkers are everywhere in this chapter. I think Dickens’s mention of Spurgeon might be an example of how modern readers may miss a Victorian reference that would be understood by the original readers of TLT. Charles Haddon Spurgeon was an evangelical Baptist preacher and, by 1857, the greatest of the preachers in London. He attracted crowds by the thousands to his sermons each week. The great cacophony of Doncaster, the betting on the races, and the drinking in the streets was a world that Spurgeon would have gleefully preached against, and the readers of TLT must have immensely enjoyed imagining such an occurrence happening.

While Idle is content to rest and observe the crowds from his hotel room, Goodchild heads out into the crowds and revels in the energy of the streets. I find this a strange way to enjoy being idle. What we learn, however, is that Goodchild (aka Dickens) had “fallen into a dreadful state concerning a pair of little lilac gloves and a little bonnet.” Idle comments how Goodchild was “lunatically seized” and that the women in the little bonnet “with her golden hair” was like glorious sunlight. This mystery woman is never given a name in chapter five. Indeed, she is referred to only as the “dear unknown wearer with the golden hair.” Now, taken on one level, this is a rather innocent and unimportant bit of writing suggesting little more than there areDoncaster attractive young ladies who enjoy the races. On another level, however, we have a more intimate and personal analysis. There is much speculation that this encounter between Goodchild and the young lady is, in fact, a reference to Dickens meeting up with Ellen Ternan. Ellen did have blond hair, was at Doncaster during the time Dickens and Collins were there, and is again slyly mentioned in some of Dickens correspondence. Shortly after Dickens returned to London from Doncaster he had a doorway covered and thus established a separate bedroom from his wife Catherine. Oh, to be a fly on the wall when Dickens and Collins talked about their time in Doncaster.

Thoughts

There is a clear change in tone between the gothic ghost tale of the previous chapter to the cacophony of chapter five. What do you think the reasons might be for this shift in tone and style?

Are you becoming weary of the format of the twin author narratives or do you enjoy this style? Why?

From your reading of the story who do you find to be the dominant author? What leads you to this decision?

In this chapter we see another instance where there may be two levels of interpreting the plot. To what extent do you think it possible that the sub-text is a story of Dickens and Ellen Ternan meeting in Doncaster?

Do you think the reference to Spurgeon was meant to be humourous, sarcastic or unintentional given the circumstances occurring in Doncaster?

To me, the ending of this story was very abrupt. What is your opinion of the ending?

What is your opinion of the complete travelogue?

Peter wrote: "The thinking is that Dickens was besotted with Ellen Ternan, and the old man wishing his wife’s death in the story is actually a psychological projection of Dickens wishing for Catherine’s death so he could be free to pursue Ellen. Well...

Peter wrote: "The thinking is that Dickens was besotted with Ellen Ternan, and the old man wishing his wife’s death in the story is actually a psychological projection of Dickens wishing for Catherine’s death so he could be free to pursue Ellen. Well...What do you think of that? ..."

I think it's just horrible. And probably true. :-(

Thank you, Peter for the explanation of the second ghost story that you gave in your review. Somehow I didn't get the compound interest analogy. Now that I get it that part of the story makes more sense, but I still don't care for it!

Can any one shed light on why the ghost was required to tell his story to two men before he could rest?

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "The thinking is that Dickens was besotted with Ellen Ternan, and the old man wishing his wife’s death in the story is actually a psychological projection of Dickens wishing for Cather..."

Hi Mary Lou

I have no idea. I will offer two suggestions, both of which come to you with the hope you take them with a grain of salt and a dash of Pickwickian humour.

Two people die because of the man’s actions, his wife and her admirer. Could it be that the ghost needed to atone for the deaths with two people who are alive?

We have two idle apprentices.

As you can see, I really have no good ideas. :-)

Hi Mary Lou

I have no idea. I will offer two suggestions, both of which come to you with the hope you take them with a grain of salt and a dash of Pickwickian humour.

Two people die because of the man’s actions, his wife and her admirer. Could it be that the ghost needed to atone for the deaths with two people who are alive?

We have two idle apprentices.

As you can see, I really have no good ideas. :-)

Peter wrote: "As you can see, I really have no good ideas. :-)

Peter wrote: "As you can see, I really have no good ideas. :-) ..."

Better than anything I've come up with. :-)

Peter, I really enjoyed your observations and possible explanations. I did enjoy these last two chapters more than the first and they held my attention much more. The ghost story did remind me of Poe somewhat although it has been awhile since I read any of his work. The last chapter I did find quite humorous and I especially enjoyed the tirade by Tom Idle about horses. That had me laughing, I loved it.

Peter, I really enjoyed your observations and possible explanations. I did enjoy these last two chapters more than the first and they held my attention much more. The ghost story did remind me of Poe somewhat although it has been awhile since I read any of his work. The last chapter I did find quite humorous and I especially enjoyed the tirade by Tom Idle about horses. That had me laughing, I loved it. As for your comments about Ellen Tirnan, I find them very disturbing as I do that whole part of Dickens character. I guess I would like to forget all about that part of his life.

I am still giving this piece only 2 stars, because I cannot really say that I "liked" it but I did enjoy certain parts of it. I am ready to move on.

Peter,

Thank you for giving the biographical background about how Dickens and Ternan first met. I never knew that she was one of the actresses he hired for "The Frozen Deep". I, too, noticed the strange detail about the "little lilac gloves" and the little bonnet, and since I knew why Dickens went to Doncaster, I was able to make head or tail of that allusion. I just wonder why it was inserted into the story. One should think that it must have been Dickens who put this obscure reference into the story because I don't think Collins would have dared to allow himself such an indiscretion with regard to his elder friend. That's why Dickens himself must have entered this detail, and this is also what I find rather amazing: Not enough that Dickens spent time with the young actress, with his wife waiting at home, but he also had to amuse himself by putting a reference to Ternan into the story? It's like playing with Victorian sensibilities, i.e. giving the reading public a hint which he knew they'd never take, and even if some of them did, the hint was innocent enough in that it could be interpreted in many different, more harmless ways.

And yes, Peter, your psychological analysis of the ghost story does make sense to me, in a very creepy way. Just consider how compelling and powerful the scene is in which the husband sternly throws that monosyllable "Die" at his wife. To think that Dickens, in a perverse way, should identify with that monster of a husband, makes me shudder.

Apart from that, I found the introduction to the story difficult to make sense of, and to be honest, I did not really get that business of these old men walking up and down the stairs, and when the ghost story started, I did not care to go back and get a better understanding of the frame of the story.

Thank you for giving the biographical background about how Dickens and Ternan first met. I never knew that she was one of the actresses he hired for "The Frozen Deep". I, too, noticed the strange detail about the "little lilac gloves" and the little bonnet, and since I knew why Dickens went to Doncaster, I was able to make head or tail of that allusion. I just wonder why it was inserted into the story. One should think that it must have been Dickens who put this obscure reference into the story because I don't think Collins would have dared to allow himself such an indiscretion with regard to his elder friend. That's why Dickens himself must have entered this detail, and this is also what I find rather amazing: Not enough that Dickens spent time with the young actress, with his wife waiting at home, but he also had to amuse himself by putting a reference to Ternan into the story? It's like playing with Victorian sensibilities, i.e. giving the reading public a hint which he knew they'd never take, and even if some of them did, the hint was innocent enough in that it could be interpreted in many different, more harmless ways.

And yes, Peter, your psychological analysis of the ghost story does make sense to me, in a very creepy way. Just consider how compelling and powerful the scene is in which the husband sternly throws that monosyllable "Die" at his wife. To think that Dickens, in a perverse way, should identify with that monster of a husband, makes me shudder.

Apart from that, I found the introduction to the story difficult to make sense of, and to be honest, I did not really get that business of these old men walking up and down the stairs, and when the ghost story started, I did not care to go back and get a better understanding of the frame of the story.

All in all, the last chapter fell flat compared with the whole of the work. On the whole, one can see - at least I think one can - that Dickens was the master-spirit in the writing of this book, but nevertheless, with the exception of the ghost story, I found the parts that were written (presumably) by Collins far superior in humour. I enjoyed sharing his rather morose point of view on that tour up the mountain, surely mainly because like Mr. Idle I cannot see the point of putting my body to exertion unless I really gain something concrete by it. Climbing a mountain for the sake of climbing a mountain is a concept alien to me, and that's why my idleness is more like Mr. Idle's than Mr. Goodchild's.

I remember one scene where Mr. Idle is lying on the sofa, and it says that he is not so much getting through the day as allowing the day to get through him. That is a memorable expression!

Likewise, I enjoyed Mr. Idle's denunciation of the horse as such, and his reflections of how a lack of proper idleness used to prove disadvantageous in his earlier life.

All in all, I liked this story, but mainly because of Mr. Idle.

I remember one scene where Mr. Idle is lying on the sofa, and it says that he is not so much getting through the day as allowing the day to get through him. That is a memorable expression!

Likewise, I enjoyed Mr. Idle's denunciation of the horse as such, and his reflections of how a lack of proper idleness used to prove disadvantageous in his earlier life.

All in all, I liked this story, but mainly because of Mr. Idle.

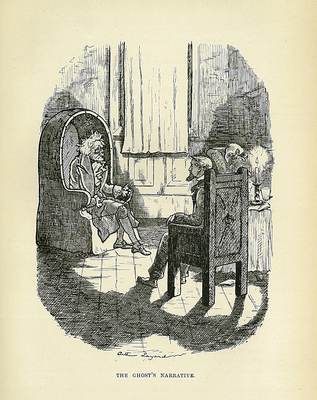

I almost forgot our last few illustrations to the story, the last ones I can find anyway:

The Ghost's Narrative

Chapter 4

Arthur Layard 1890

Text Illustrated:

A chilled, slow, earthy, fixed old man. A cadaverous old man of

measured speech. An old man who seemed as unable to wink, as if

his eyelids had been nailed to his forehead. An old man whose

eyes--two spots of fire--had no more motion than if they had been

connected with the back of his skull by screws driven through it,

and rivetted and bolted outside, among his grey hair.

The night had turned so cold, to Mr. Goodchild's sensations, that

he shivered. He remarked lightly, and half apologetically, 'I

think somebody is walking over my grave.'

'No,' said the weird old man, 'there is no one there.'

Mr. Goodchild looked at Idle, but Idle lay with his head enwreathed

in smoke.

'No one there?' said Goodchild.

'There is no one at your grave, I assure you,' said the old man.

He had come in and shut the door, and he now sat down. He did not

bend himself to sit, as other people do, but seemed to sink bolt

upright, as if in water, until the chair stopped him.

'My friend, Mr. Idle,' said Goodchild, extremely anxious to

introduce a third person into the conversation.

'I am,' said the old man, without looking at him, 'at Mr. Idle's

service.'

'If you are an old inhabitant of this place,' Francis Goodchild

resumed.

'Yes.'

'Perhaps you can decide a point my friend and I were in doubt upon,

this morning. They hang condemned criminals at the Castle, I

believe?'

'_I_ believe so,' said the old man.

'Are their faces turned towards that noble prospect?'

'Your face is turned,' replied the old man, 'to the Castle wall.

When you are tied up, you see its stones expanding and contracting

violently, and a similar expansion and contraction seem to take

place in your own head and breast. Then, there is a rush of fire

and an earthquake, and the Castle springs into the air, and you

tumble down a precipice.'

His cravat appeared to trouble him. He put his hand to his throat,

and moved his neck from side to side. He was an old man of a

swollen character of face, and his nose was immoveably hitched up

on one side, as if by a little hook inserted in that nostril. Mr.

Goodchild felt exceedingly uncomfortable, and began to think the

night was hot, and not cold.

As for the artist:

Little biographical information is known about water colorist and illustrator Major Arthur Layard. He produced work between 1894 and 1911, illustrating books and contributing to periodicals including The Pall Mall Magazine and Fun. Layard worked in Hammersmith and in Pangbourne between 1902 and 1903. He exhibited at the Bruton Gallery and the New English Art Club. Layard is remembered principally for his figurative illustrations. An illustrator, poster designer and painter born Arthur Austen Macgregor Layard he fought in the Sudan Campaign in 1885 and gained the rank of Major in the service of the Royal Engineers.

The Ghost's Narrative

Chapter 4

Arthur Layard 1890

Text Illustrated:

A chilled, slow, earthy, fixed old man. A cadaverous old man of

measured speech. An old man who seemed as unable to wink, as if

his eyelids had been nailed to his forehead. An old man whose

eyes--two spots of fire--had no more motion than if they had been

connected with the back of his skull by screws driven through it,

and rivetted and bolted outside, among his grey hair.

The night had turned so cold, to Mr. Goodchild's sensations, that

he shivered. He remarked lightly, and half apologetically, 'I

think somebody is walking over my grave.'

'No,' said the weird old man, 'there is no one there.'

Mr. Goodchild looked at Idle, but Idle lay with his head enwreathed

in smoke.

'No one there?' said Goodchild.

'There is no one at your grave, I assure you,' said the old man.

He had come in and shut the door, and he now sat down. He did not

bend himself to sit, as other people do, but seemed to sink bolt

upright, as if in water, until the chair stopped him.

'My friend, Mr. Idle,' said Goodchild, extremely anxious to

introduce a third person into the conversation.

'I am,' said the old man, without looking at him, 'at Mr. Idle's

service.'

'If you are an old inhabitant of this place,' Francis Goodchild

resumed.

'Yes.'

'Perhaps you can decide a point my friend and I were in doubt upon,

this morning. They hang condemned criminals at the Castle, I

believe?'

'_I_ believe so,' said the old man.

'Are their faces turned towards that noble prospect?'

'Your face is turned,' replied the old man, 'to the Castle wall.

When you are tied up, you see its stones expanding and contracting

violently, and a similar expansion and contraction seem to take

place in your own head and breast. Then, there is a rush of fire

and an earthquake, and the Castle springs into the air, and you

tumble down a precipice.'

His cravat appeared to trouble him. He put his hand to his throat,

and moved his neck from side to side. He was an old man of a

swollen character of face, and his nose was immoveably hitched up

on one side, as if by a little hook inserted in that nostril. Mr.

Goodchild felt exceedingly uncomfortable, and began to think the

night was hot, and not cold.

As for the artist:

Little biographical information is known about water colorist and illustrator Major Arthur Layard. He produced work between 1894 and 1911, illustrating books and contributing to periodicals including The Pall Mall Magazine and Fun. Layard worked in Hammersmith and in Pangbourne between 1902 and 1903. He exhibited at the Bruton Gallery and the New English Art Club. Layard is remembered principally for his figurative illustrations. An illustrator, poster designer and painter born Arthur Austen Macgregor Layard he fought in the Sudan Campaign in 1885 and gained the rank of Major in the service of the Royal Engineers.

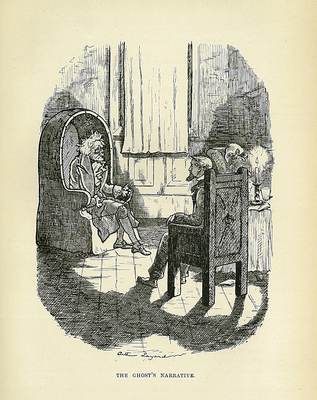

In The Bride's Chamber

Chapter 4

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

Hours upon hours he held her by the arm when her arm was black where he held it, and bade her Die!

"It was done, upon a windy morning, before sunrise. He computed the time to be half-past four; but, his forgotten watch had run down, and he could not be sure. She had broken away from him in the night, with loud and sudden cries — the first of that kind to which she had given vent — and he had had to put his hands over her mouth. Since then, she had been quiet in the corner of the paneling where she had sunk down; and he had left her, and had gone back with his folded arms and his knitted forehead to his chair.

"Paler in the pale light, more colourless than ever in the leaden dawn, he saw her coming, trailing herself along the floor towards him — a white wreck of hair, and dress, and wild eyes, pushing itself on by an irresolute and bending hand.

"'O, forgive me! I will do anything. O, sir, pray tell me I may live!'

'"Die!'

'"Are you so resolved? Is there no hope for me?'

'"Die!'

"Her large eyes strained themselves with wonder and fear; wonder and fear changed to reproach; reproach to blank nothing. It was done.

Commentary:

Although Furniss's illustration renders the climactic scene of the interpolated tale in the Collins-Dickens collaborative novella dramatically, the short story is told in the limited omniscient, giving the reader access to the thoughts and feelings not of the victim-bride but of the psychopathic groom.

First published as the fourth of five parts in Household Words over the course of October 1857, the inset narrative, called either "The Bride's Chamber" or "In The Bride's Chamber" from its chief setting, has often appeared in collections of ghost stories and Victorian tales of the supernatural. The Gothic tale reveals the influence of Edgar Allen Poe in its diabolical, self-justifying central character and blameless, malleable victim, but Furniss actually puts a face to the murderer and clearly establishes an eighteenth-century setting in the costumes and wainscoted room with the ornate, leaded pane window. Furniss suggests the killer's derangement by his distorted visage and bulging eyes, and represents the twenty-one-year-old bride's virginal innocence by her white gown and gesture of supplication. Although hardly "half-witted," in Furniss's illustration the bride is certainly "frightened" and "submissive" some three weeks after her marriage to her former guardian and de facto step-father. Deborah Thomas reasonably speculates about the autobiographical implications of the madman's willing his wife to die as Dickens was shortly to separate from his wife of twenty years and forge a liaison with eighteen-year-old actress Ellen Ternan.

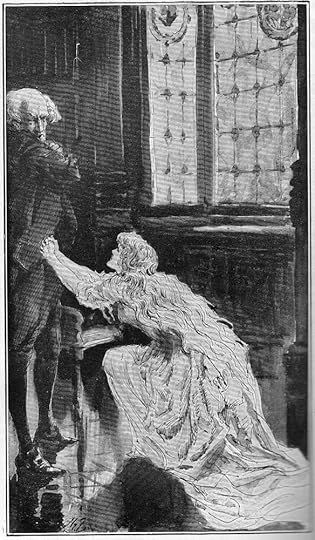

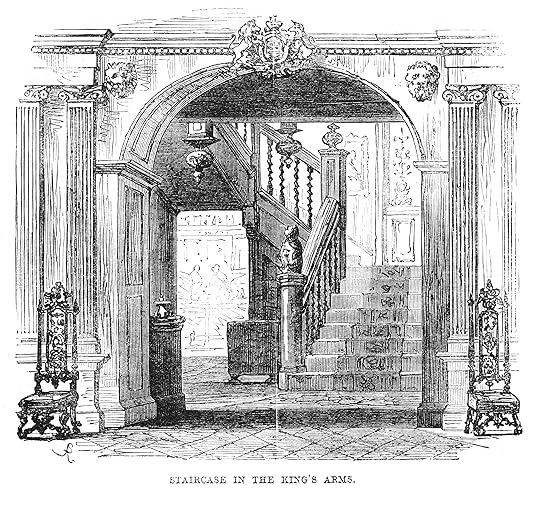

The Illustrated London News

"Staircase in The Kings Arms, Lancaster"

(where Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins stayed)

From John Weedy's collection

Commentary:

An account of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins stay at the Kings Arms Hotel, Lancaster researched by John Weedy and taken from “Dickensian Inns and Taverns” by B.W. Matz

In the late autumn of 1857. Dickens and Wilkie Collins started " on a ten or twelve days' expedition to out-of-the-way places, to do (in inns and coast corners) a little tour in search of an article and in avoidance of railroads."

Their selection was the Lake District, but the outcome of their expedition was not one article merely but a series of five under the title of The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, written in collaboration. The two idle apprentices were Francis Goodchild and Thomas Idle, the first name being the pseudonym of Dickens.

These misguided young men, they inform us in the narrative, " were actuated by the low idea of making a perfectly idle trip in any direction. They had no intention of going anywhere in particular; they wanted to see nothing ; they wanted to know nothing ; they wanted to learn nothing ; they wanted to do nothing. They wanted only to be idle . . . and they were both idle in the last degree." In that spirit they set forth on their journey.

Carrock Fell, Wigton, Allonby, Carlisle, Maryport, Hesket Newmarket, were all visited in turn, and the adventures of the twain in these spots duly set forth in the pages of the book. In due course they came to Lancaster, and, the inn at that town being the most important of the tour, we deal with it first.

The travelers were meditating flight at the station on account of Thomas Idle being suddenly filled with " the dreadful sensation of having something to do." However, they decided to stay because they had heard there was a good inn at Lancaster, established in a fine old house; an inn where they give you bride-cake every day after dinner. " Let us eat bride-cake," they said " without the trouble of being married, or of knowing anybody in that ridiculous dilemma." And so they departed from the station and were duly delivered at the fine old house at Lancaster on the same night.

This was the King's Arms in the Market Street, the exterior of which was dismal, quite uninviting, and lacked any sort of picturesqueness such as one associates with old inns ; but the interior soon compensated for the unattractiveness of the exterior by its atmosphere, fittings and customs. Being then over two centuries old, it had allurement calculated to make the lover of things old happy and contented. " The house was a genuine old house,' the story tells us, " of a very quaint description, teeming with old carvings, and beams, and panels, and having an excellent staircase, with a gallery or upper staircase cut off from it by a curious fence-work of old oak, or of old Honduras mahogany wood. It was, and is, and will be, for many a long year to come, a remarkably picturesque house; and a certain grave mystery lurking in the depth of the old mahogany panels, as if they were so many deep pools of dark water, such, indeed, as they had been much among when they were trees—gave it a very mysterious character after nightfall.

" A terrible ghost story was attached to the house concerning a bride who was poisoned there, and the room in which the process of slow death, took place was pointed out to visitors. The perpetrator of the crime, the story relates, was duly hanged and in memory of the weird incident bride-cake was served each day after dinner.

The complete story of this melodramatic legend is narrated to Goodchild by a specter in the haunted chamber where he and his companion had been writing.

Dickens wove into the story much fancy and not a little eeriness, and it is said that the publicity given to it in Household Words, in which it first appeared, created so much interest that the hotel was sought out by eager visitors who love a haunted chamber. As this was situated in an ancient inn with its antique bedstead all complete, to say nothing of the curious custom of providing bride-cake at dinner in memory of the unfortunate bride, the King's Arms, Lancaster, discovered its fame becoming world-wide instead of remaining local.

At the time of the visit of Dickens and Collins to this rare old inn, the proprietor was one Joseph Sly, and Dickens occupied what he termed the, state bedroom, " with two enormous red four-posters in it, each as big as Charley's room at Gads Hill." He described the inn as "a very remarkable old house . . . with genuine rooms and an uncommonly quaint staircase." A certain portion of the " lazy notes " for the book were, we are told, written at the King's Arms Hotel.

On their arrival Dickens and Collins sat down to a good hearty meal. The landlord himself presided over the serving of it, which, Dickens writes in a letter, comprised " two little salmon trout ; a sirloin steak ; a brace of partridges ; seven dishes of sweets ; five dishes of dessert, led off by a bowl of peaches ; and in the center an enormous bride-cake. ' We always have it here, sir,' said the landlord, ‘custom of the house.' Collins turned pale, and estimated the dinner at half a guinea each."

Mr. Sly became quite good friends with the two distinguished novelists, and cherished with great pride the signed portrait of Dickens which the author of Pickwick presented him with. He left the old place in 1879 and it was soon afterwards pulled down and replaced by an ordinary commercial hotel. Although the bride-cake custom was abandoned, and the haunted chamber with its fantastic story swept away, it is interesting to know that the famous oak bed-stead, in which Dickens himself slept, was acquired by the Duke of Norfolk.

Mr. Sly, who died in 1895, never tired of recalling the visit of the two famous authors. He took the greatest pride in his wonderful old inn, and found real delight in conducting visitors over the building and telling amusing stories about Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Indeed he was so proud of the association that he obtained Dickens permission to reprint those passages of The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices relating to the hostelry in pamphlet form, with an introductory note saying, "The reader is perhaps aware that Mr Charles Dickens and his friend Wilkie Collins, in the year 1857, visited Lancaster, and during their sojourn stayed at Mr. Sly's King's Arms Hotel."

There is a further association with the inn and Dickens to be found in " Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions." We find it recorded there that Doctor Marigold and his Library Cart, as he called his caravan, " were down at Lancaster, and I had done two nights' more than the fair average business (though I cannot in honor recommend them as a quick audience) in the open square there, near the end of the street where Mr. Sly's King's Arms and Royal Hotel stands."

" Doctor Marigold " was published in 1865, seven years after Dickens's visit. But he not only remembered the King's Arms, but also Mr. Sly, the proprietor, who thus became immortalized in a Dickens story. Mr. Sly evidently was a popular man in the town, and his energy and good nature were much appreciated. That this was so, the following paragraph bears witness : It is recorded as an historical fact that, on the marriage of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the demonstration made in Lancaster exceeded any held out of the Metropolis. The credit of this success is mainly due to Mr. Sly, who proposed the program, which included the roasting of two oxen whole, and a grotesque torchlight procession. The manner in which the whole arrangements were carried out was so satisfactory to the inhabitants of the town and neighborhood that, at a meeting held a short time after the event, it was unanimously resolved to present Mr. and Mrs. Sly with a piece of plate, of a design suitable to commemorate the event. The sum required was subscribed in a few days, the piece of plate procured, and the presentation was made in the Assembly Rooms on the 9th of November by the High Sheriff, W. A. F. Saunders, Esq., of Wennington Hall, in the presence of a numerous company.

In its palmy days the King's Arms was a prominent landmark for travellers en route to Morecambe Bay, Windermere, the Lakes, and Scotland. It was erected in 1625, and in the coaching era was the head hotel in the town for general posting purposes, and was the most suitable place for tourists to break their journey going North, or in returning. Consequently, it was one of the most important in the North.

"Staircase in The Kings Arms, Lancaster"

(where Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins stayed)

From John Weedy's collection

Commentary:

An account of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins stay at the Kings Arms Hotel, Lancaster researched by John Weedy and taken from “Dickensian Inns and Taverns” by B.W. Matz

In the late autumn of 1857. Dickens and Wilkie Collins started " on a ten or twelve days' expedition to out-of-the-way places, to do (in inns and coast corners) a little tour in search of an article and in avoidance of railroads."

Their selection was the Lake District, but the outcome of their expedition was not one article merely but a series of five under the title of The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, written in collaboration. The two idle apprentices were Francis Goodchild and Thomas Idle, the first name being the pseudonym of Dickens.

These misguided young men, they inform us in the narrative, " were actuated by the low idea of making a perfectly idle trip in any direction. They had no intention of going anywhere in particular; they wanted to see nothing ; they wanted to know nothing ; they wanted to learn nothing ; they wanted to do nothing. They wanted only to be idle . . . and they were both idle in the last degree." In that spirit they set forth on their journey.

Carrock Fell, Wigton, Allonby, Carlisle, Maryport, Hesket Newmarket, were all visited in turn, and the adventures of the twain in these spots duly set forth in the pages of the book. In due course they came to Lancaster, and, the inn at that town being the most important of the tour, we deal with it first.

The travelers were meditating flight at the station on account of Thomas Idle being suddenly filled with " the dreadful sensation of having something to do." However, they decided to stay because they had heard there was a good inn at Lancaster, established in a fine old house; an inn where they give you bride-cake every day after dinner. " Let us eat bride-cake," they said " without the trouble of being married, or of knowing anybody in that ridiculous dilemma." And so they departed from the station and were duly delivered at the fine old house at Lancaster on the same night.

This was the King's Arms in the Market Street, the exterior of which was dismal, quite uninviting, and lacked any sort of picturesqueness such as one associates with old inns ; but the interior soon compensated for the unattractiveness of the exterior by its atmosphere, fittings and customs. Being then over two centuries old, it had allurement calculated to make the lover of things old happy and contented. " The house was a genuine old house,' the story tells us, " of a very quaint description, teeming with old carvings, and beams, and panels, and having an excellent staircase, with a gallery or upper staircase cut off from it by a curious fence-work of old oak, or of old Honduras mahogany wood. It was, and is, and will be, for many a long year to come, a remarkably picturesque house; and a certain grave mystery lurking in the depth of the old mahogany panels, as if they were so many deep pools of dark water, such, indeed, as they had been much among when they were trees—gave it a very mysterious character after nightfall.

" A terrible ghost story was attached to the house concerning a bride who was poisoned there, and the room in which the process of slow death, took place was pointed out to visitors. The perpetrator of the crime, the story relates, was duly hanged and in memory of the weird incident bride-cake was served each day after dinner.

The complete story of this melodramatic legend is narrated to Goodchild by a specter in the haunted chamber where he and his companion had been writing.

Dickens wove into the story much fancy and not a little eeriness, and it is said that the publicity given to it in Household Words, in which it first appeared, created so much interest that the hotel was sought out by eager visitors who love a haunted chamber. As this was situated in an ancient inn with its antique bedstead all complete, to say nothing of the curious custom of providing bride-cake at dinner in memory of the unfortunate bride, the King's Arms, Lancaster, discovered its fame becoming world-wide instead of remaining local.

At the time of the visit of Dickens and Collins to this rare old inn, the proprietor was one Joseph Sly, and Dickens occupied what he termed the, state bedroom, " with two enormous red four-posters in it, each as big as Charley's room at Gads Hill." He described the inn as "a very remarkable old house . . . with genuine rooms and an uncommonly quaint staircase." A certain portion of the " lazy notes " for the book were, we are told, written at the King's Arms Hotel.

On their arrival Dickens and Collins sat down to a good hearty meal. The landlord himself presided over the serving of it, which, Dickens writes in a letter, comprised " two little salmon trout ; a sirloin steak ; a brace of partridges ; seven dishes of sweets ; five dishes of dessert, led off by a bowl of peaches ; and in the center an enormous bride-cake. ' We always have it here, sir,' said the landlord, ‘custom of the house.' Collins turned pale, and estimated the dinner at half a guinea each."

Mr. Sly became quite good friends with the two distinguished novelists, and cherished with great pride the signed portrait of Dickens which the author of Pickwick presented him with. He left the old place in 1879 and it was soon afterwards pulled down and replaced by an ordinary commercial hotel. Although the bride-cake custom was abandoned, and the haunted chamber with its fantastic story swept away, it is interesting to know that the famous oak bed-stead, in which Dickens himself slept, was acquired by the Duke of Norfolk.

Mr. Sly, who died in 1895, never tired of recalling the visit of the two famous authors. He took the greatest pride in his wonderful old inn, and found real delight in conducting visitors over the building and telling amusing stories about Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Indeed he was so proud of the association that he obtained Dickens permission to reprint those passages of The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices relating to the hostelry in pamphlet form, with an introductory note saying, "The reader is perhaps aware that Mr Charles Dickens and his friend Wilkie Collins, in the year 1857, visited Lancaster, and during their sojourn stayed at Mr. Sly's King's Arms Hotel."

There is a further association with the inn and Dickens to be found in " Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions." We find it recorded there that Doctor Marigold and his Library Cart, as he called his caravan, " were down at Lancaster, and I had done two nights' more than the fair average business (though I cannot in honor recommend them as a quick audience) in the open square there, near the end of the street where Mr. Sly's King's Arms and Royal Hotel stands."

" Doctor Marigold " was published in 1865, seven years after Dickens's visit. But he not only remembered the King's Arms, but also Mr. Sly, the proprietor, who thus became immortalized in a Dickens story. Mr. Sly evidently was a popular man in the town, and his energy and good nature were much appreciated. That this was so, the following paragraph bears witness : It is recorded as an historical fact that, on the marriage of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the demonstration made in Lancaster exceeded any held out of the Metropolis. The credit of this success is mainly due to Mr. Sly, who proposed the program, which included the roasting of two oxen whole, and a grotesque torchlight procession. The manner in which the whole arrangements were carried out was so satisfactory to the inhabitants of the town and neighborhood that, at a meeting held a short time after the event, it was unanimously resolved to present Mr. and Mrs. Sly with a piece of plate, of a design suitable to commemorate the event. The sum required was subscribed in a few days, the piece of plate procured, and the presentation was made in the Assembly Rooms on the 9th of November by the High Sheriff, W. A. F. Saunders, Esq., of Wennington Hall, in the presence of a numerous company.

In its palmy days the King's Arms was a prominent landmark for travellers en route to Morecambe Bay, Windermere, the Lakes, and Scotland. It was erected in 1625, and in the coaching era was the head hotel in the town for general posting purposes, and was the most suitable place for tourists to break their journey going North, or in returning. Consequently, it was one of the most important in the North.

It isn't easy to see, but here is the playbill of The Frozen Deep with Ellen Ternan's name on it. She is playing, if I'm reading this right and there is no guarantee that I am, Miss Crayford whoever that is.

And while I'm at it, here is a sample of the overture:

http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/te...

And while I'm at it, here is a sample of the overture:

http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/te...

Thank you for the illustrations, Kim! Furniss really captures the gothic atmosphere for me here, and his figures are this time far less elf-like than usual.

As to Ellen Ternan as Dickens's real reason for going to Doncaster, sometimes it is better not to know too much because it can be quite disillusioning. Poor Catherine!

As to Ellen Ternan as Dickens's real reason for going to Doncaster, sometimes it is better not to know too much because it can be quite disillusioning. Poor Catherine!

Tristram wrote: "Thank you for the illustrations, Kim! Furniss really captures the gothic atmosphere for me here, and his figures are this time far less elf-like than usual.

As to Ellen Ternan as Dickens's real re..."

Yes. Recent research has turned up letters that point out the fact that Dickens attempted to have Catherine admitted to an asylum. He was not successful, but is rather upsetting to consider. I wonder if he and his fellow lazy apprentice ever talked about such a plan ... and then came Collins’s The Woman in White.

As to Ellen Ternan as Dickens's real re..."

Yes. Recent research has turned up letters that point out the fact that Dickens attempted to have Catherine admitted to an asylum. He was not successful, but is rather upsetting to consider. I wonder if he and his fellow lazy apprentice ever talked about such a plan ... and then came Collins’s The Woman in White.

Peter, just picture me with my eyes shut and my hands stopping my ears, singing nanananaaana :-)

Tristram wrote: "Peter, just picture me with my eyes shut and my hands stopping my ears, singing nanananaaana :-)"

Duly noted. :-)

Duly noted. :-)

Well, this shortish piece of writing is a pleasant interlude. With Nell behind us and BR looming ahead of us, this week we can gear down a bit and idle away some time with Dickens and Collins. Collins is portrayed as my type of idler. Slow, perhaps even in park. Dickens seems completely unable to ever settle down, slow down, let alone idle away any time at all.

Biographies and autobiographies are wonderful to read, but pose some danger when readers try to find the bits, pieces, and major currents of the author in their novels. I, for one, always look for shadows of the author’s life experiences in their work and this text is a perfect case in point. Briefly, then, here is some more information to build on what Tristram mentioned last week. The background information will present some interesting speculation on both Dickens’s life as well as look at the literary interest of TLT.

Collins and Dickens co- wrote the play “The Frozen Deep” and its first dress rehearsal was 5 January 1857. This was followed by a series of small personal performances. Douglas Jerrold, a mutual friend of Collins and Dickens died, and Collins and Dickens decided to perform some benefit performances of The Frozen Deep and present the proceeds to Jerrold’s family. More and larger performances of the play followed, culminating in a scheduled performance in Manchester to be performed for an audience of 4000. Dickens realized that his eldest daughters, who were performing in the smaller venues, would not be able to project to such a large audience, and so he hired professional actors to take his daughters’ parts. The people he hired was a Mrs Ternan and her daughters, and thus Dickens first met Ellen Ternan. It appears that Dickens became quickly besotted with Ellen. Some of his existing letters reveal his emotions at the time. After the Manchester performances, the Ternan family was scheduled to perform in Doncaster. Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens decided to do research for some travelogues for Household Words and they (surprisingly?) set off for Doncaster as well.

What we find in chapter’s four and five of The Idle Tour of the Two Apprentices can be interpreted in many ways. Let’s take a tour ourselves of these two fascinating - and perhaps revealing - chapters.

Idle, our friend Wilkie Collins, offers us a succinct comment about Goodchild when he says “you can’t play, you don’t know what it is. You make work of everything.” How true. In the beginning of chapter four we see Mr Idle quite content to rest his mind, body, and especially his foot in the hotel room. Goodchild, in contrast, decides to visit a lunatic asylum where he finds particular interest in an inmate who picks away at the matting on the floor. Goodchild wonders if there is a philosophical meaning to the man’s actions. Such thoughts are not followed up in any detail. It’s as if Goodchild loses interest in his own philosophical question. The next thing we know we are back at the Inn having dinner.

What follows in an interesting description of the Inn. This description folds into a focus on the mystery of some of the other apparent lodgers at the Inn. There are “half-a -dozen noiseless old men in black, all dressed exactly alike, who [glide] up the stairs.” Now, here is some activity, some mystery, for our two idle apprentices to think about, discuss, and perhaps even speculate on. We feel the shift of the chapter turning upon these men. There is yet another layer of mystery that occurs. Idle and Godchild’s door opens and closes at unexpected moments. Further discussions of the old men occur between Idle and Goodchild.

Our apprentices stay up late, the church bell tolls one, and one of the old men appears at the authors’ door. The mysterious man is described as “cadaverous.” He is unable to wink and it looks like “his eyelids had been nailed to his forehead.”

Now this is getting interesting, and it is a bit disconcerting to Goodchild who feels cold and comments that it feels as if someone is walking over his grave. After that comment from Goodchild, the old man assures him that there is “no one there.” The old man enters the room and seems to be very familiar with the nature of a person hanging.

Thoughts

To what extent has this meeting between our idle apprentices and this old man engaged your curiosity? Why?

What elements of the gothic story are appearing in this tale?

What elements of the ghost story do you look forward to most?

Briefly, the old man tells a story about love, hate, and the manipulation of a will. A man, the narrator of the story who turns out to be a ghost, recounts how he appointed himself the guardian and ward of a 10 year old girl, sends her to a horrid school for 11 years, and then coerces her to marry him. He then continually harasses and haunts her by saying “Now die! I have done with you” until she does die and he gets possession of her fortune. One night, the man sees a young man in a tree who turns out to be an admirer of his dead young bride. The husband kills the boy with a bill hook and buries his body by the tree. One of the boughs of the tree, however, begins to grow into the form of the dead young man. Times passes. The tree is hit by lightning and the boy’s body is found buried under the tree. The man is arrested. The dead bride returns to haunt the old man with the word “live” and the youth with the bill hook also haunts the old man. The old man is eventually hanged. The Bride- cakes of the Inn serve as an echo reminder of the death of the innocent girl.

Each separate hour the dead old man is doomed to divide into another until 12 noon. We learn that the multiple men represent the percent of gain the old man accrued. This is his curse until he can tell his story to two living men. A bit of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” perhaps? In any case, the two living men turn out to be Idle and Goodfellow.

Thoughts

Was this a convincing story?

And now for a biographical note that you might find interesting. One speculation is that Dickens wrote this story with his wife in mind. The thinking is that Dickens was besotted with Ellen Ternan, and the old man wishing his wife’s death in the story is actually a psychological projection of Dickens wishing for Catherine’s death so he could be free to pursue Ellen. Well...

What do you think of that?