The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

Chuzzlewit, Chapters 45 - 47

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Tristram wrote: " and to be sure it was not just me who disliked it, I read it to my 12-month-old daughter,"

Tristram wrote: " and to be sure it was not just me who disliked it, I read it to my 12-month-old daughter,"Your daughter is a year old already? Wow time goes fast, it will be Christmas before we know it. Well in 121 days anyway. :-}

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,this week's instalment was really a textbook example of what is brilliant and inimitable, moving and hilarious in Dickens ... and what is cheesy, soppy and tawdry.

Of c..."

In chapter 45 one of the things that jumped out at me was when Tom and Ruth went to dine with John Westlock. I was afraid we were going to go through the "running downstairs for flour, then eggs, then butter, water, rolling-pin, etc." Luckily we were spared that. :-}

Do we know what the secret was that was so awful Montague had such a hold on Jonas? I have an idea, but I can't remember if the book ever made it clear.

Do we know what the secret was that was so awful Montague had such a hold on Jonas? I have an idea, but I can't remember if the book ever made it clear.

I was wondering, does Pecksniff and Cherry really believe the things said about them? Do they believe they are as "good" as Dickens says they are? Or do they know how awful they are deep down inside. Or maybe not so deep. Pecksniff is described as:

I was wondering, does Pecksniff and Cherry really believe the things said about them? Do they believe they are as "good" as Dickens says they are? Or do they know how awful they are deep down inside. Or maybe not so deep. Pecksniff is described as:"a moral man; a grave man, a man of noble sentiments, and speech...Perhaps there never was a more moral man...

Mr Pecksniff's manner was so bland, and he nodded his head so soothingly, and showed in everything such an affable sense of his own excellence, that anybody would have been, as Mrs Lupin was, comforted by the mere voice and presence of such a man; and, though he had merely said 'a verb must agree with its nominative case in number and person, my good friend,' or 'eight times eight are sixty-four, my worthy soul,' must have felt deeply grateful to him for his humanity and wisdom.

Primed in this artful manner, Mr Pecksniff presented himself at dinner-time in such a state of suavity, benevolence, cheerfulness, politeness, and cordiality, as even he had perhaps never attained before. The frankness of the country gentleman, the refinement of the artist, the good-humoured allowance of the man of the world; philanthropy, forbearance, piety, toleration, all blended together in a flexible adaptability to anything and everything; were expressed in Mr Pecksniff, as he shook hands with the great speculator and capitalist."

Obviously Dickens doesn't think Pecksniff a shield of virtue, we don't either, but does Pecksniff truly believe it? Also the same of Charity:

"it is not in my nature to add to the uneasiness of any person....I have much to make me humble and contented."

And Charity, with her fine strong sense and her mild, yet not reproachful gravity, was so well named....

Miss Pecksniff was quite gracious to Miss Pinch in this triumphant introduction; exceedingly gracious. She was more than gracious; she was kind and cordial.

Until Augustus leads me to the altar he is not sure of me. I have blighted and withered the affections of his heart to that extent that he is not sure of me. I see that preying on his mind and feeding on his vitals. What are the reproaches of my conscience, when I see this in the man I love!' "

Does she really believe this about herself? Or does she know what an awful person she is. She is my least favorite person in the book. Her and Jonas that is.

I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. I, too, keep looking for evidence that he is putting on his airs, that he is slyly smiling to himself, that he his aware of his own acting ability, but can't find anything. He is more than self-absorbed in himself, he is self-consumed by himself. His character, to my reading, has gone from acceptance, to disbelief, to enjoying the satire, to the horror at the possibility that someone like him could actually exist.

I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. I, too, keep looking for evidence that he is putting on his airs, that he is slyly smiling to himself, that he his aware of his own acting ability, but can't find anything. He is more than self-absorbed in himself, he is self-consumed by himself. His character, to my reading, has gone from acceptance, to disbelief, to enjoying the satire, to the horror at the possibility that someone like him could actually exist.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,this week's instalment was really a textbook example of what is brilliant and inimitable, moving and hilarious in Dickens ... and what is cheesy, soppy and tawdry.

Of c..."

Tristram

I'm sure your daughter fell asleep in your arms because you evidenced so much love and affection in reading Dickens's colourful words and characters that she wanted to snooze so as not to distract you from your continuing enjoyment. ;>}

Peter wrote: "I'm sure your daughter fell asleep in your arms because you evidenced so much love and affection in reading Dickens's colourful words...."

Peter wrote: "I'm sure your daughter fell asleep in your arms because you evidenced so much love and affection in reading Dickens's colourful words...."She fell asleep because like myself, she can't understand half the words he uses anyway. :o}

Peter wrote: "I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. ."

Peter wrote: "I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. ."On the contrary, he fully understands the greatness of his character, his fine qualities as an architect and teacher of architects, his excellence as a parent, and his noble kindness to all faithful friends and pupils.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. ."

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I think Pecksniff is, as horrible as it is to believe, completely oblivious to the true odiousness of his own character. ."On the contrary, he fully understands the greatness of his..."

You're a nut, have I ever told you that? If I haven't it's merely an oversight. :o}

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow-Pickwickians,this week's instalment was really a textbook example of what is brilliant and inimitable, moving and hilarious in Dickens ... and what is cheesy, soppy a..."

Hmmmm, the magic of Dickens's words pacifying a one-year old girl is a wonderful thought. You have made my day there, Peter!

As to the question if Pecksniff really believes in his own hypocrisy, I think this is hard to tell. I remember from Seinfeld that George Costanza once said, "If you believe it yourself, it's no longer a lie".

As to the question if Pecksniff really believes in his own hypocrisy, I think this is hard to tell. I remember from Seinfeld that George Costanza once said, "If you believe it yourself, it's no longer a lie".There are several scenes when Jonas as well as his father Anthony rebuke Pecksniff for putting on his mask of virtue even in the family circle where he should know better than to imagine anyone believing him, and he does not even react to these reproaches but carries on his charades. Maybe he is so taken in with himself that he really believes in his own deception.

There are other situations, e.g. when Pecksniff boasts to himself of being able to wind old Martin round his little finger, or when he threatens Mary with regard to destroying all hopes in life young Martin might still entertain, or when he cleverly prepares his denunciation of Tom Pinch, which make the reader assume that Pecksniff is very rational and cold about his schemes and that he knows very well what he is doing. The beginning of Chapter 44 also suggests that Pecksniff is actually not really imbued with a sense of moral superiority but just putting it on, playing to the galleries,

"It was a special quality, among the many admirable qualities possessed by Mr Pecksniff, that the more he was found out, the more hypocrisy he practised. Let him be discomfited in one quarter, and he refreshed and recompensed himself by carrying the war into another. If his workings and windings were detected by A, so much the greater reason was there for practicing without loss of time on B, if it were only to keep his hand in."

What I also think very interesting is that Dickens even has Pecksniff fall prey to a Freudian slip once, in Chapter 30:

"'But I have ever,' said Mr Pecksniff, 'sacrificed my children's happiness to my own—I mean my own happiness to my children's—and I will not begin to regulate my life by other rules of conduct now.'"

This also, to me, seems evidence of his knowing better and wilfully suppressing the truth.

As to Charity, I'd consider her a chip off the old block.

Tristram wrote: "As to the question if Pecksniff really believes in his own hypocrisy, I think this is hard to tell. I remember from Seinfeld that George Costanza once said, "If you believe it yourself, it's no lon..."

Tristram wrote: "As to the question if Pecksniff really believes in his own hypocrisy, I think this is hard to tell. I remember from Seinfeld that George Costanza once said, "If you believe it yourself, it's no lon..."Tristram

You offer a very reasonable and articulate commentary. Pecksniff's character is certainly well crafted, and when you make reference to George Costanza I can see the similarity between those two characters. Never thought of such a connection. I have known, as I'm sure most of us have, people with Pecksniffian tendencies. Dickens's light just shines brighter.

Yes Kim, I've been wondering the same about Montague and Jonas. Maybe I missed something.

Yes Kim, I've been wondering the same about Montague and Jonas. Maybe I missed something.As to Mr Pecksniff's worthiness or sense of his own worth, I can only suggest:

Pecksniff is worthy

Pecksniff is nice

In the mind of the Grinch

Who never thinks twice.

Hilary wrote: "Yes Kim, I've been wondering the same about Montague and Jonas. Maybe I missed something.

Hilary wrote: "Yes Kim, I've been wondering the same about Montague and Jonas. Maybe I missed something.As to Mr Pecksniff's worthiness or sense of his own worth, I can only suggest:

Pecksniff is worthy

Pecks..."

I certainly agree that the Grinch, our Grinch anyway never thinks twice. I'll look for you on television at the Penn State game on Saturday. :o}

Hilary wrote:

Hilary wrote: "In the mind of the Grinch

Who never thinks twice. "

If you think right the first time,

you can only do harm by thinking twice.

Hilary wrote: "Boom Tish, Everyman. I like your thinking! ;-)"

Hilary wrote: "Boom Tish, Everyman. I like your thinking! ;-)"Since Everyman has never agreed with me on anything he obviously has never thought right in his life so he must be thinking twice and doing harm all the time. :o}

Kim wrote: "Since Everyman has never agreed with me on anything he obviously has never thought right in his life so he must be thinking twice and doing harm all the time. :o}

Kim wrote: "Since Everyman has never agreed with me on anything he obviously has never thought right in his life so he must be thinking twice and doing harm all the time. :o}"

Since I did agree with you about Tristram being a grump, your statement is false. Therefore you're the one who needs to think twice, and does the harm all the time.

Ah, logic is wonderful. You should try it sometime.

Everyman wrote: "Since I did agree with you about Tristram being a grump, your statement is false. Therefore you're the one who needs to think twice, and does the harm all the time.

Everyman wrote: "Since I did agree with you about Tristram being a grump, your statement is false. Therefore you're the one who needs to think twice, and does the harm all the time. Ah, logic is wonderful. You should try it sometime. ..."

Absolutely not. Logic is too much like math, you like it you can have it. It was nice to see that you did agree with me at least once about something though.

I enjoyed Charity's rather acid tongue and good for Tom to continue to grow his backbone as he stands up to Jonas.

I enjoyed Charity's rather acid tongue and good for Tom to continue to grow his backbone as he stands up to Jonas.Chapter 47 is pure Dickens at its height. The opening to the chapter is so well crafted and drawn I wanted it to go on and on, but yet we all have to die sometime and Montague is a nasty piece of work. Did anyone else feel a bit of E A Poe seeping into the writing? When Jonas' mind hears his "heart beating Murder Murder. Murder in the bed." Also, when Dickens writes of Jonas as he looks at himself in the mirror Dickens uses the phrase "a tell-tale face."

Could this be a little nod to their connection?

Peter,

Peter,that is a very interesting cross reference - all the more so as "The Telltale Heart" was written around the time MC appeared in print. I often feel that Dickens has a Poe-esque vein, or Poe a Dickensian one, when it comes to describing the inner life of villains after their gory deeds (or before them). The glimpses into Jonas's mind are among the finest passages in MC - just consider the dream he has before he sets out to kill Montague, and his fear of returning home and finding the ghost of his victim in the little room he uses to provide himself an alibi.

In Oliver Twist we have the scene in which Bill Sikes roams the countryside after his murder of Nancy, a scene which is also quite moving but which is not as strong and deep as the Jonas chapters here. There, however, I was deeply impressed with the scene of Fagin's execution and his waiting for it in his prison cell.

When we arrive at Our Mutual Friend there will be similar scenes ...

Books mentioned in this topic

Oliver Twist (other topics)Our Mutual Friend (other topics)

this week's instalment was really a textbook example of what is brilliant and inimitable, moving and hilarious in Dickens ... and what is cheesy, soppy and tawdry.

Of course, this is a matter of discussion, and even if it means discussing tastes, which is an idle thing to do, we might still be able to agree on elements of style that make us like or dislike a particular passage of writing.

So the following summary of the chapters will be highly subjective - and I hope you'll let me get away with it.

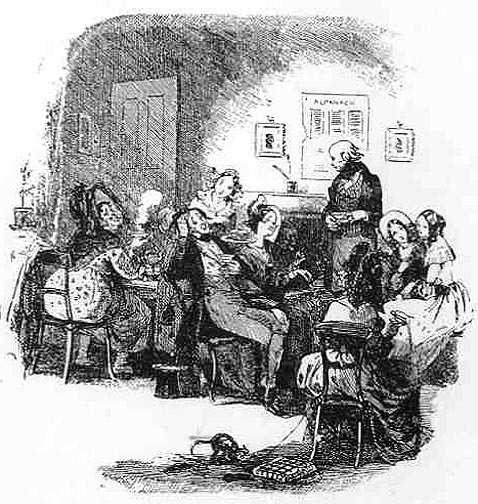

In Chapter 45 the only seemingly important thing to happen is that John Westlock realizes that somebody might have a spell on Jonas for whatever reason. Apart from that we are led down the valley of purple prose, where its stickiest flowers grow and ooze their ten-a-penny fragrences. Just take the recurring "Oh foolish, panting, timid little heart" addresses and you know what I mean. I'm actually afraid it is going to get worse as soon as John Westlook starts opently courting Ruth. - By the way, in order to test the quality of the chapter and to be sure it was not just me who disliked it, I read it to my 12-month-old daughter, and before I was even halfway through, she had fallen asleep!

Chapters 46 and 47 are quite different, though, and bear witness of the inimitable skill of Dickens as a creator of comedy, drama and high tension. In Chapter 46, there is only one annoying thing: Why should Merry behave to a complete stranger like this:

"Poor Merry held the hand of cheerful little Ruth between her own, and listening with evident pleasure to all she said, but rarely speaking herself, sometimes smiled, and sometimes kissed her on the cheek, and sometimes turned aside to hide the tears that trembled in her eyes."

She may be a reformed character, but this display of meekness and sentiment is somewhat over the top.

But then what a wonderful stage Dickens gives to Mrs. Gamp again and to her blundering figures of speech - "if I may make so bold as speak so plain of what is plain enough to them as needn't look through millstones, Mrs Todgers, to find out wot is wrote upon the wall behind" - and of malapropisms - "in this promiscous place". And how she tries to win the favour of everyone, except Chuffey! The comedy is mixed with and gradually gives way to a more serious and dramatic tone, e.g. through Mr. Chuffey.

Then, in Chapter 47, we really get insight into a murderer' mind, and the murder itself is described in a way that may well have been a blueprint for a movie script.

Again, this is just my personal opinion, and I'd like to know how well Chapter 45 went down with you, and how you liked the following chapters.