Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses discussion

The Metamorphoses - The 15 Books

>

Book Two - 19th November 2018

message 51:

by

Roman Clodia

(new)

Nov 22, 2018 06:14AM

Thanks, Roger - I like this one. It seems to me that Europa is the dominant figure here, while Jupiter/the bull looks rather exhausted! She seems to be actively riding him rather than simply being carried away by him. I like the stillness of her in the midst of all that movement - as you say, her expression is opaque. Is she looking back to where they've come from or forward to where they're headed? I also like that this plays down her nudity/sexuality.

Thanks, Roger - I like this one. It seems to me that Europa is the dominant figure here, while Jupiter/the bull looks rather exhausted! She seems to be actively riding him rather than simply being carried away by him. I like the stillness of her in the midst of all that movement - as you say, her expression is opaque. Is she looking back to where they've come from or forward to where they're headed? I also like that this plays down her nudity/sexuality.

reply

|

flag

One more pictorial query:

One more pictorial query:

Above are three details, from Titian's Rape of Europa, Boucher's Jupiter and Callisto, and Rubens' Assumption of the Virgin. What is it with all these Cupids, putti, amoretti, or whatever else you want to call them? Isn't it interesting that Renaissance and later painters turned to the same symbols to show divinity, regardless of whether it was of the Christian or pagan kind? R.

Fionnuala wrote: "

Fionnuala wrote: "How amazing it must be to stand beneath such a tumbl..."

Thank you... I hope the posting of images brings out the text in a different way...

And yes, the Phaeton is a perfect subject for a ceiling depiction.

Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the na..."

Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the na..."Thank you, Roger.... No I did not know this image... intriguing indeed, as you say... Europa seems somewhat blasée about it all.

The image is also striking because the bull, the sea, and even Europa seem petrified. Out of stone.

I will be posting on Europa later on, as I have read the text more closely, and there are certainly many to chose from.. I wonder why was it such a popular subject.

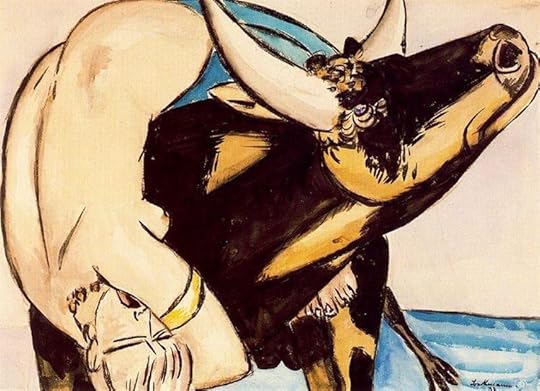

But today I was the whole day in a Symposium on the German painter Max Beckmann, at the Thyssen museum, and they showed this one, which I had never seen before.

Max Beckmann. 1933. Private Collection.

Check the year... the political charge is substantial....

Roman Clodia wrote: "Women authors in the C16th-17th centuries seem to be more attracted to Ovid's Heroides which enable female authorship.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Women authors in the C16th-17th centuries seem to be more attracted to Ovid's Heroides which enable female authorship. ..."

I guess I will have to read the Heroids after the Met..

:)

Roger wrote: "the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him br..."

Roger wrote: "the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him br..."Yes, and remember that this ceiling medallion Jordaens painted for his own mansion.

I liked the 'overperfumed' expression for Moreau... I agree he is somewhat of an 'acquired taste' - but many of the younger French painters found him very inspiring.... I don't like the lion - the rest I do.. so fantastical...

Kalliope wrote: "Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever,..."

Kalliope wrote: "Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever,..."What a powerful, evocative image from Beckmann! I cannot believe for a moment that Jove's selection of a bull as disguise in the original Europa store (upon which Ovid based his account) was anything less than a ribald story-teller's choice aimed at titillating the young men of his day. The snorting, aggressive, testosterone-driven image is impossible to ignore.

Jim wrote: "I cannot believe for a moment that Jove's selection of a bull as disguise in the original Europa store (upon which Ovid based his account) was anything less than a ribald story-teller's choice…"

Jim wrote: "I cannot believe for a moment that Jove's selection of a bull as disguise in the original Europa store (upon which Ovid based his account) was anything less than a ribald story-teller's choice…"Well maybe. But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud? R.

Substantial indeed, Kalliope—wow! Was Beckmann's art eventually classed as degenerate?

Substantial indeed, Kalliope—wow! Was Beckmann's art eventually classed as degenerate?I repeat my earlier remark about serendipity. You have this apparent knack of synchronizing you seminars to whatever we shall be discussing, but in advance! R.

Roger wrote: "

Roger wrote: "I might as well post the great Titian painting of Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy, one of the seven "poesies," or scenes from Ovid, painted for P..."

I have just reread the Callisto episode and looked again at your images, Roger. All very powerful and effective in their different way. I have paid more attention to the earlier scene, that of the seduction for, as you say, it provided a 'different' erotic scene. It makes me wonder how they were perceived by either gender.... Interesting that at least three Bouchers have survived. My favourite is the Kansas one.

I also like the Rubens (I always like the Rubens)...

Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting.

Courbet. Le Sommeil. 1866. Petit Palais, Paris.

One of my editions (I am juggling three) has a note on the last line of the Callisto episode. She is identified as a daughter of Lycaeon. This is an inconsistency for in theory all human kind were destroyed with the exception of Deucalion and Pyrrha.

One of my editions (I am juggling three) has a note on the last line of the Callisto episode. She is identified as a daughter of Lycaeon. This is an inconsistency for in theory all human kind were destroyed with the exception of Deucalion and Pyrrha.

Jim wrote: "The snorting, aggressive, testosterone-driven image is impossible to ignore. ..."

Jim wrote: "The snorting, aggressive, testosterone-driven image is impossible to ignore. ..."Yes. Impossible to ignore.

Roger wrote: "But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud?..."

Roger wrote: "But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud?..."That may be is the only attractive aspect of Jupiter, his malleability - always in the service of lechery and deceit, though... He is a comical figure...

Of all the 'creations' or 're-creations' of the universe, before it was first put in order or after a disaster, this is the first time that Jupiter has any doing in the restoration.

He not only stops the Phaeton disaster but also checks that everything is back in order -- paying closer attention to 'his' area, Arcadia, and as soon as it is possible, identifying his next pray. Incorrigible.

Anyway, all the previous times, it was not him the 'doer'.

Kalliope wrote: "Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting..."

Kalliope wrote: "Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting..."There is also the even more daring painting by Courbet (which I won't reproduce) in the Orsay, called something like "The Origin of the World."

But is it a different theme? Literally, of course. But one also feels that these myths arose as ways of explaining difficult things, and same-sex attraction is surely one of them. R.

Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:

Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:The full moon is so fierce that I can count the

coconuts' cross-hatched shade on bungalows,

their white walls raging with insomnia.

The stars leak drop by drop on the tin plates

of the sea almonds, and the jeering clouds

are luminously rumpled as the sheets.

The surf, insatiably promiscuous,

groans through the walls; I feel my mind

whiten to moonlight, altering that form

which daylight unambiguously designed,

from a tree to a girl's body bent in foam;

then, treading close, the black hump of a hill,

its nostrils softly snorting, nearing the

naked girl splashing her naked breasts with silver.

Both would have kept their proper distance still,

if the chaste moon hadn't swiftly drawn the drapes

of a dark cloud, coupling their shapes.

She teases with those flashes, yes, but once

you yield to human horniness, you see

through all that moonshine what they really were,

those gods as seed-bulls, gods as rutting swans

an overheated farmhand's literature.

Who ever saw her pale arms hook his horns,

her thighs clamped tight in their deep-plunging ride,

watched, in the hiss of the exhausted foam,

her white flesh constellate to phosphorous

as in salt darkness beast and woman come?

Nothing is there, just as it always was,

but the foam's wedge to the horizon-light,

then, wire-thin, the studded armature,

like drops still quivering on his matted hide,

the hooves and horn-points anagrammed in stars.

And here is another EUROPA, a rather more difficult one, by James Merrill (1948):

And here is another EUROPA, a rather more difficult one, by James Merrill (1948):The air is sweetest that a thistle guards.The image of "cloud-whites on porcelain" in the final stanza makes me think of the bas-relief below by Giovanni Francesco Rustici, in storage in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is unusual among representations of the Europa story for several reasons: it is very early (1495), it is sculptural rather than a painting, and Jupiter is clearly already beginning to enjoy the fruits of his latest capture! R.

But the lean scholar, reading Buffon and Horace,

Shuts his brown book, marking the place with a flower

Picked from the fragrant riot below his terrace,

And the sea rings with doubloons and the blossoming words

Of no poet are cleanly about him in a loud shower.

Those feasts, the jubilant quince and bursting pear,

The Judas tree and page in the wind rinsed.

He watches the young laundress of the shore

With blueing and suds rear linen virginals

In sprays of gold, her cloths, white birds, careless;

She stands like any maiden loved by Zeus.

His murkiest deeds, night-thoughts that hammer him

Upon his bed, are charmed into the light,

As might on one day of each year at noon

All creatures of the midnight wake and fly

In a fine sport under the lavish sun

To greet once what they are least succored by:

His dark thoughts whirl until they fall unconscious,

And the warm noon stoops over them then, anxious,

Passionate— ah, the ceremony of rape!

Rape, though of no flesh, nor of mind indeed,

But of the eye, in gauzes negligent,

That, scorched by the flowering nostrils, overstreams.

Then sudden ease: beyong the straits, the climb

Ecstatic of cloud-whites on porcelain, while

Supinely through high morning like a girl

Innocence glides, dipping a wrist in time,

On a white bull of cloud, a full white belle

Smiling, a bridal in the wastes of pearl.

In the thread for book one Kalliope wondered: "I keep asking myself how Ovid's contemporary readers reacted to this poem."

In the thread for book one Kalliope wondered: "I keep asking myself how Ovid's contemporary readers reacted to this poem."Now, the story of Phaethon's fateful ride reads like an antique episode of "The Fast and the Furious". I can imagine that Roman youngsters having read this at school hasted to get home and to borrow (or to pilfer) their father's quadriga and try out, whether they can do better than the half-good. The story is vivid and rich, the characters lively and the action so compelling that the reader - like Phaeton - is unable to stop it before its fatal end. Highly enjoyable.

One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus, the pinchers of Cancer, the throat of Leo and the venomous sting of Scorpio, but also the arrows of Sagittarius and the floods of Eridanus close to the horizon.

One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus, the pinchers of Cancer, the throat of Leo and the venomous sting of Scorpio, but also the arrows of Sagittarius and the floods of Eridanus close to the horizon.And later we learn the story of Ursus Maior (or the "septem triones" - sever trios of plough oxen or the seven stars of the Big Dipper, as I was told it is called in the US) and Ursus Minor, who previously used to be Callisto and her son Arcas. These two constellations are indeed always visible in our latitudes, i.e. in the imagination of the Romans never sink into the sea - "ne puro tingatur in aequore praelex" (2, 530). Reading Ovid I also understand the etymology of the Italian word for north "settentrione".

Callisto made it even twice to the sky. One of the "Galilean" moons of Jupiter is called Callisto, besides Io, Europa and Ganymede. But they were not known, before Galileo discovered them with a telescope.

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the horns of Taurus..."

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the horns of Taurus..."You're right. The Met. serves as an alternative handbook to the natural world—expressed in human terms, which makes it so delightful! R.

Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:

Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:Livid and meagre were her looks, her eye

In foul distorted glances turn’d awry;

A hoard of gall her inward parts possess’d,

And spread a greenness o’er her canker’d breast;

Her teeth were brown with rust, and from her tongue,

In dangling drops, the stringy poison hung.

Vit wrote: "Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:

Vit wrote: "Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:Livid and meagre were her looks, her eye

In foul distorted glances turn’d awry; ..."

That is indeed magnificent! Is it the Garth/Dryden translation? R.

Roger wrote: "Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:

Roger wrote: "Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:The full moon is so fierce that I can count the

coc..."

Wow! Now THAT is operatic!

What a hoot that would be to stage!

Jim wrote: "WOW! Now THAT is operatic!"

Jim wrote: "WOW! Now THAT is operatic!"Thanks, Jim. I'm relieved that someone is reading these more off-topic things. I realize that I tend to stray in my postings from Ovid, through translations of Ovid, through historical responses to Ovid, to other artists (as here) revisiting his stories. But it is precisely this Protean fecundity that fascinates me about the collection.

As for staging it, I wouldn't. How could you match Walcott's images? But were I a composer, I would be sorely tempted. R.

I know we mentioned it earlier in this thread, but the story Callisto upsets me. This was clearly rape - Ovid even mentions that she actively resists ("illa quidem pugnat" 2, 436) - but still it is the woman who gets banished and blamed using words of criminal and moral malfeasance ("crimen", "poena" and "iniuria"). I hope that also Ovid's contemporates (male and female) groaned reading of such injustice.

I know we mentioned it earlier in this thread, but the story Callisto upsets me. This was clearly rape - Ovid even mentions that she actively resists ("illa quidem pugnat" 2, 436) - but still it is the woman who gets banished and blamed using words of criminal and moral malfeasance ("crimen", "poena" and "iniuria"). I hope that also Ovid's contemporates (male and female) groaned reading of such injustice.On a totally different note: Do the English translations convey the humour of the scene, when the raven tells Phoebus that Coronis is with another man? In German as well as in Latin ("et pariter vultusque deo plectrumque colorque excidit" 2,601) the list of nouns going with this one verb sounds very funny. I can easily imagine Apollon's face drop along with the plectrum of his instrument.

Thank you to all of you for posting such beautiful images, paintings etc. It's so inspiring while reading the Metamorphosis! The following book has been recommended to me a couple of years ago:

Thank you to all of you for posting such beautiful images, paintings etc. It's so inspiring while reading the Metamorphosis! The following book has been recommended to me a couple of years ago: Classical Myths in Italian Renaissance Painting

Peter wrote: "I know we mentioned it earlier in this thread, but the story Callisto upsets me. This was clearly rape - Ovid even mentions that she actively resists ("illa quidem pugnat" 2, 436) - but still it is..."

Peter wrote: "I know we mentioned it earlier in this thread, but the story Callisto upsets me. This was clearly rape - Ovid even mentions that she actively resists ("illa quidem pugnat" 2, 436) - but still it is..."Raeburn, the translation I am reading, doesn’t quite capture the humor of Apollo’s response to the raven. Rereading the passage I can see that his laurel wreath droops, his plectrum and his face fall, but it takes three verbs in three clauses. This is the problem with translation, of course. Latin is more compressed apparently. In English it is difficult to group many different nouns around one verb without using adverbs and prepositions. I appreciate your posting the Latin.

I am having trouble finding much comedy in Ovid so far. For example, before the reader can react to the funny bird story Apollo immediately shoots Coronis and her unborn child, which overwhelms the reader with outrage.

Peter @75: I have not read enough of Ovid in the original yet to know whether all the stories like Callisto's are so clearly framed as rapes. But I am a little surprised, since the Renaissance viewpoint that gave us all those pictures, operas, and other artworks, tends to be much more romantic.

Peter @75: I have not read enough of Ovid in the original yet to know whether all the stories like Callisto's are so clearly framed as rapes. But I am a little surprised, since the Renaissance viewpoint that gave us all those pictures, operas, and other artworks, tends to be much more romantic.You are absolutely right about the witty use of zeugma (or is it syllepsis?) in Ovid's account. I have looked at four English translations. All attempt something similar, but few succeed so well. Here (slightly longer) are the renderings by Garth, Humphries, Martin, and Miller (prose):

The God was wroth, the colour left his look,So yes, translators have noticed what Ovid did. But Latin is a so much more compressible language. R.

The wreath his head, the harp his hand forsook;

His silver bow and feather'd shafts he took,

And lodg'd an arrow in the tender breast,

That had so often to his own been prest.

The god lost countenance, and color also,

His laurel crown came sliding off his forehead,

He dropped his lyre, and, as his anger mounted,

He took the bow, he bent it, fired the arrow

Into the breast he had felt against his own.

The laurel resting on his brow slipped down;

in not as much time as it takes to tell,

his face, his lyre, his high color fell!

When that charge was heard the laurel glided from the lover's head; together countenance and color changed, and the quill dropped from the hand of the god.

HistoryGirl @77. Seems we were posting at the same time, and have made similar points. Can you possibly quote the Raeburn to add to this little anthology? R.

HistoryGirl @77. Seems we were posting at the same time, and have made similar points. Can you possibly quote the Raeburn to add to this little anthology? R.

When he heard of his lover’s defection, Apollo’s laurel-wreath slipped, his colour faded, his jaw then dropped, and his plectrum fell to the ground. His wounded heart was seething and swelling with anger. He seized his familiar weapons and, flexing his bow from its horn tips, fired his arrow, which none can escape, to transfix the bosom, [605] the lovely bosom he’d pressed to his own in their many embraces.

When he heard of his lover’s defection, Apollo’s laurel-wreath slipped, his colour faded, his jaw then dropped, and his plectrum fell to the ground. His wounded heart was seething and swelling with anger. He seized his familiar weapons and, flexing his bow from its horn tips, fired his arrow, which none can escape, to transfix the bosom, [605] the lovely bosom he’d pressed to his own in their many embraces.Raeburn translation

Thanks, Historygirl. You are right: four verbs (slipped, faded, dropped, fell), whereas Latin could probably have done it all in one, though I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath.

Thanks, Historygirl. You are right: four verbs (slipped, faded, dropped, fell), whereas Latin could probably have done it all in one, though I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath.You mention that Latin is good for this sort of thing. Which makes me question the extent to which Ovid's contemporaries would have seen it as especially witty. When Alexander Pope writes:

Here Thou, great Anna! whom three Realms obey,we smile, partly because the linking of counsels of state to a cup of tea is so bathetic, and partly because the Latin-derived construct is unusual in English. But the four attributes of Apollo that fall are not so sharply contrasted, and the construction is relatively idiomatic. So I repeat: how witty would Ovid's readers have found it? R.

Dost sometimes Counsel take—and sometimes Tea.

May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own:

May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own:First, there are the stories themselves, i.e. the exploits and peccadilloes of gods and mortals

Second, there are the artistic renderings of those stories in the form of poem (by Ovid and others), prose, painting, sculpture, opera (libretto, music, production), film (and dare we contemplate video game?)

And third, there is the individual psychic realization of those artistic manifestations as experienced by people (including ourselves) over the centuries, each one colored by one's own, personality, beliefs etc.)

The experience of the stories and the telling of them is different in each of us. That is the essence of art; no two people experience it in exactly the same way; and two people's response to a single rendition may be diametrically opposite.

Hence, a discussion such as the one we're having.

Roger wrote: "hough I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath... So I repeat: how witty would Ovid's readers have found it?"

Roger wrote: "hough I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath... So I repeat: how witty would Ovid's readers have found it?"Ovid indeed uses a different verb for the laurel "laurea delapsa", i.e. participle of "delabi" = to drop. I guess only a trained classicist will be able to ultimately answer your question. I can only add that the German translation by Michael von Albrecht is mimicking the Latin construction ("entglitt ihm der Lorbeer und der Gott verlor zugleich die Fassung, das Plectrum und die Gesichtsfarbe") and indeed gives you a smile when reading.

Jim wrote: "May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own...."

Jim wrote: "May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own...."Thank you, Jim; a very useful taxonomy. I would divide your classification into four, however, separating the tellings by Ovid from the retellings by other artists who have read their Ovid. If we could show that any of these later versions entirely bypassed Ovid, that would be a different matter.

The point of your third category (or my fourth), I would imagine, is to encourage discussion, by saying that all points of view are equally welcome. True, and thank you for it. But I would suggest that our individual reactions are shaped by the particular source. We respond differently to the Callisto or Europa stories as told by Ovid from how we do when hearing Cavalli or looking at Titian. R.

My response to some episodes reading them today would surely be different from what my response must have been as a callow youth fifty years ago. I vaguely recall reading a few of the stories (including the Europa story) that long ago; I was a far more cynical fellow at that time, so I doubt if I gave them the work the credit it deserved. I believe that the first time Ovid made a significant impression on me was through a production of Guck's Orpheo in the early 1970s. I then went looking for Ovid to see what else I had missed earlier but I don't recall being much impressed. The opera had the powerful advantage of gorgeous music.

My response to some episodes reading them today would surely be different from what my response must have been as a callow youth fifty years ago. I vaguely recall reading a few of the stories (including the Europa story) that long ago; I was a far more cynical fellow at that time, so I doubt if I gave them the work the credit it deserved. I believe that the first time Ovid made a significant impression on me was through a production of Guck's Orpheo in the early 1970s. I then went looking for Ovid to see what else I had missed earlier but I don't recall being much impressed. The opera had the powerful advantage of gorgeous music.My point here is that the number of permutations in our exoerience can be limitless.

Jim wrote: "My point here is that the number of permutations in our experience can be limitless. "

Jim wrote: "My point here is that the number of permutations in our experience can be limitless. "That is true indeed. My point, which is complementary to it, is that our experiences are somewhat shaped by the artist who led us to them. Your response to Orfeo was conditioned by Gluck. It is this process of intermediation that so interests me as an interpreter. And, as an opera director, I am dealing with still more layers: the original story, the work of the composer and librettist, my own interpretation in staging it, the further contributions of the conductor and singers, and even the way I translate the text in the supertitles. R.

Excellent food for thought, Jim and Roger. Ovid himself, of course, is also a mediator, rather than originator, of many of these myths. It's easy to slip into thinking of his versions as sources in their own right.

Excellent food for thought, Jim and Roger. Ovid himself, of course, is also a mediator, rather than originator, of many of these myths. It's easy to slip into thinking of his versions as sources in their own right. I don't know the Gluck opera but the Orpheus story as told by Ovid is also in dialogue with earlier versions in Plato (The Symposium) and Virgil's Georgics. So there are already multiple layers in play even before we start thinking of later receptions as Roger details so neatly.

I still haven't got to reading Book 2, will hopefully correct this week!

Thanks, RC. We will get to the Orpheus story later, I am sure. But it may be worth noting its status as the subject of the earliest operas we know (first decade of the 17th century), and the most composed subject for a good while thereafter. No doubt because the hero himself is a musician, and it is the beauty of his singing that wins over the powers of the underworld. R.

Thanks, RC. We will get to the Orpheus story later, I am sure. But it may be worth noting its status as the subject of the earliest operas we know (first decade of the 17th century), and the most composed subject for a good while thereafter. No doubt because the hero himself is a musician, and it is the beauty of his singing that wins over the powers of the underworld. R.

That's interesting about the link between Orpheus and opera as he presumably chanted poetry to the lyre (cf. 'lyric') rather than sang as we understand the term - sorry, that's a nerdy snippet! Will hold off further till we come to the Orpheus story.

That's interesting about the link between Orpheus and opera as he presumably chanted poetry to the lyre (cf. 'lyric') rather than sang as we understand the term - sorry, that's a nerdy snippet! Will hold off further till we come to the Orpheus story.

On thematic links between stories:

On thematic links between stories: Callisto 'fought back; but indeed what man could a girl be a match for | let alone Jupiter?' (2.436-7) reminded me of Phaethon, not a 'match' for his father in driving the chariot of the sun.

Both Callisto and Phaethon are overcome by Jupiter: Apollo complains about the unfairness of Jupiter's action with the thunderbolt ('once he has tested the power of my fire-footed horses, he'll learn | that failure to keep them under control doesn't merit destruction!', 2.393-4), while as readers we surely bridle at the asymmetry that Jupiter rapes, Callisto is punished: actually a triple punishment - she's raped, she's exiled by Diana, she's turned into a bear by Juno. The world of the Met. is not one conspicuous for its natural justice.

We can also find parallels with Io in that Callisto is silenced ('her powers of speech were wrested away,' 2.483), but her human consciousness still remains, at odds with her body: 'but though her body was now a bear's, her emotions were human,' 2.485.

I loved the imaginative details of Callisto being afraid of other bears, and her son Arcas (who is born human - weird!) who is distressed at the way she's staring at him and almost kills her. This story really seems to press the boundaries between animal and human, almost erasing all difference between them.

How interesting, then, that so many of the paintings focus on the erotic 'courtship' of Jupiter-as-Diana - there's nothing erotic, it seems to me, in Ovid's telling.

Book 2 also ends with a broken off, unfinished story as Europa is carried away - this self-conscious device of drawing attention to the artificiality of narrative itself is often seen as postmodern... how nice to see it already in use in Ovid!

Book 2 also ends with a broken off, unfinished story as Europa is carried away - this self-conscious device of drawing attention to the artificiality of narrative itself is often seen as postmodern... how nice to see it already in use in Ovid!

I wonder if anyone has a theory as to why Ovid left the Europa story unfinished at the end of Book II? Dramatic tension would appear an unlikely reason (as we see today where dramatic TV series are sometimes left hanging to induce the audience to take up the series again at the start of a new season) since his audience undoubtedly already knew how the story went. Do we even know if there was a time lapse between Ovid's release of Books II ans III? Seems unlikely since Books I thru VI seem to have been written in 8 AD.

I wonder if anyone has a theory as to why Ovid left the Europa story unfinished at the end of Book II? Dramatic tension would appear an unlikely reason (as we see today where dramatic TV series are sometimes left hanging to induce the audience to take up the series again at the start of a new season) since his audience undoubtedly already knew how the story went. Do we even know if there was a time lapse between Ovid's release of Books II ans III? Seems unlikely since Books I thru VI seem to have been written in 8 AD.

Jim wrote: "I wonder if anyone has a theory as to why Ovid left the Europa story unfinished at the end of Book II?"

Jim wrote: "I wonder if anyone has a theory as to why Ovid left the Europa story unfinished at the end of Book II?"My reading is that one of Ovid's prime concerns throughout the Met. (and, indeed, his other works) is how literature 'works'. He plays lots of narrative games in the Met. especially with stories that, as you say, he knows his audience knows. So he expands some, contracts others, plays around with levels of narrators with inset stories and so on. Having a story like Europa being left unfinished perhaps draws attention to the artificiality of story-telling which is based on a beginning-middle-end.

I'm interested that you say Books 1-6 were written in 8 CE (sorry!) - my understanding is that the whole of the Met. was written before his exile but that Ovid continued to revise it. I didn't think the individual books were released separately.

Roger wrote: "Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much

Roger wrote: "Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much."

Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17 and the following was shown...

Cornelis van Poelenburgh. First Half C17. Hermitage.

Apart from the lovely landscape, I find interesting the whole 'coterie' of nymphs and the very subtle depiction of the tension when Diana is discovering Callisto's state.... Two of the nymphs are looking with apprehension at the goddess and Callisto is looking away.

We do not see Diana's face..

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus..."

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus..."Peter, when I read this passage I thought of the comment you would be writing on this - giving us a further insight.

I had not thought of the etymology of 'settentrione' - in Spanish 'septentrional'.

Thank you.

Kalliope wrote: "Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17' and the following was shown..."

Kalliope wrote: "Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17' and the following was shown..."Indeed this is a lovely picture, Kalliope, and quite unknown to me. But it is hard to understand its storytelling at this scale, so I am providing a close-up:

At first, I thought that the Diana/Calisto pair was the couple at top left of this detail, one of whom seems indeed to be looking at the naked belly of the other. But no, Diana is the one with the yellow robe around her hips and the rather fashionable scarf, and Calisto [I can't use the double-L spelling to a Spanish-speaker] is the one being held by the two other nymphs several feet away and below her. So yes, subtle as you say, but a little too much so for clarity. The plethora of other nymphs is indicated in Ovid, and par for the course in painting, but what are those two doing at top left? R.

Roger wrote: "I am providing a close-up:.."

Roger wrote: "I am providing a close-up:.."Thank you for the close-up, Roger. It is needed... The landscape was Poelenburgh's interest, but for us it is the Callisto story.

It was unknown to me until this afternoon.

Indeed, Diana is the one with the yellow robe... but whose face we cannot see, as I said above... the expressions of the nymphs who look at her act almost as mirrors for us to 'see' the horror that the goddess is discovering...

The whole scene also has a certain 'domestic' (and Dutch) aspect - showing other nymphs engaged in other activities, still oblivious of Callisto's drama.

All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail . . . ?

All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail . . . ?He may have been mostly interested in landscape, but all the same he manages a really effective—and I would have said original—grouping of the figures in that descending diagonal. So utterly different from the Titian/Rubens approach, and quite beautiful. R.

Roger wrote: "All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail "

Roger wrote: "All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail "I'm sorry, Roger, but I am afraid I don't hold the key to 'explaining' Poelenburgh's painting.

As I said, I see all the other nymphs in the complete picture as forming a 'domestic' arrangement - we are peeking into their private coterie: bathing, talking to each other and then the 'drama' of the pregnancy discovery. And I put the inverted commas to the 'domestic' because it is a quality so often associated with Dutch (bourgeois) painting -- an idea that the Seminar I have been attending has been trying to dilute - but which still pervades the approach to story-painting, however incidental in a landscape, in C17 Netherlands.

But may be you see something else.

Poelenburgh painted many more landscapes with Nymphs. They were very successful amongst his patrons which included King Charles I.

And there is at least one more with Callisto and Diana - this one in a private collection in NY.

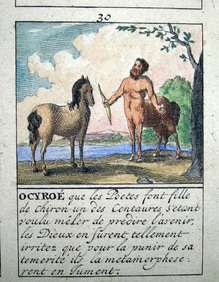

Of the Ocyrhoe story I have found only engravings.

Of the Ocyrhoe story I have found only engravings.Antonio Tempesta. 1606.

But she is shown as half human, like her father the Centaur Chiron, although she wonders in the text why she has been metamorphosed into a complete mare instead of retaining half her human figure.

This other one seems to be closer to the text... Rather nice, I think.

Books mentioned in this topic

Le bain de Diane (other topics)After Ovid: New Metamorphoses (other topics)

The Penelopiad (other topics)

Metamorphica (other topics)

The Penelopiad (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Pierre Klossowski (other topics)Euripides (other topics)