The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Nicholas Nickleby

>

N N Chapters 6 - 10

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 9

Well, that was ... that was ... interesting. I have yet to see where this is going, but I've had more than enough of the Squeers. Let's let Nicholas fend for himself for a while.

Anyone..."

Xan

John’s accent certainly is strong and I had some difficulty working it out. As to Tilda and John being a likely couple to marry I wonder if it is a case whereby the majority of people in the north (or anywhere for that matter) at that time period never ventured far from their place of birth. Also, we know that Dotheboys is located in a rural area. I would imagine that the opportunity to meet many different marital prospects was limited. Thus, when an offer came, it may be the only, or at least, one of the few that were likely to occur. Certainly Fanny was quite eager to snatch Nicholas. Unlike Tilda who was still in her teens, Fanny was in her mid-twenties and thus running out of time to be seen as a good marriage prospect.

That, and, of course, who would want Squeers as a father- in-law?

:-))

Well, that was ... that was ... interesting. I have yet to see where this is going, but I've had more than enough of the Squeers. Let's let Nicholas fend for himself for a while.

Anyone..."

Xan

John’s accent certainly is strong and I had some difficulty working it out. As to Tilda and John being a likely couple to marry I wonder if it is a case whereby the majority of people in the north (or anywhere for that matter) at that time period never ventured far from their place of birth. Also, we know that Dotheboys is located in a rural area. I would imagine that the opportunity to meet many different marital prospects was limited. Thus, when an offer came, it may be the only, or at least, one of the few that were likely to occur. Certainly Fanny was quite eager to snatch Nicholas. Unlike Tilda who was still in her teens, Fanny was in her mid-twenties and thus running out of time to be seen as a good marriage prospect.

That, and, of course, who would want Squeers as a father- in-law?

:-))

I wouldn't want her mother as a mother-in-law either, Peter.

I wouldn't want her mother as a mother-in-law either, Peter. I actually didn't see anything bad about Fanny. I mean she lives where her options aren't many, her looks aren't the greatest, and her parents are her role models. Kind of felt sorry for her. Now her brother . . . well . . . let's not talk about him.

By the way did you notice Matilda say to Nicholas that Fanny's dress was beautiful and her looks were the best she could do?

Are we seeing a right-eye thing about these Squeers, here? I've seen the reference several times now, and poor Fanny wasn't lucky enough to escape the family plague.

I agree with what you say above, but I'm still wondering why his accent/dialect is so different from everyone else's from around those parts?

I'm also wondering if that accent was easier for readers of the 1840s to understand than for us? Cause between him and the coachman, I'm giving up translating.

I'm also wondering if that accent was easier for readers of the 1840s to understand than for us? Cause between him and the coachman, I'm giving up translating.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm also wondering if that accent was easier for readers of the 1840s to understand than for us? Cause between him and the coachman, I'm giving up translating."

Xan

The accent issue is interesting. None of the Squeers family have any trace of one, nor does Tilda. I doubt we could say the Squeers were so educated that one could not expect a trace of a strong northern accent.

Could it be as simple as Dickens just being Dickens and assigning the dialect as little more than a quirky character trait with a slight nod to authenticity?

Xan

The accent issue is interesting. None of the Squeers family have any trace of one, nor does Tilda. I doubt we could say the Squeers were so educated that one could not expect a trace of a strong northern accent.

Could it be as simple as Dickens just being Dickens and assigning the dialect as little more than a quirky character trait with a slight nod to authenticity?

I couldn't understand a word of John Browdie either. I got impression that this was by design, and Dickens wanted to make him a primitive caveman character, but why, I don't know.

I couldn't understand a word of John Browdie either. I got impression that this was by design, and Dickens wanted to make him a primitive caveman character, but why, I don't know.

I just got to the scene where John Browdie is introduced. Good to know I should not try and struggle too much in figuring out what he says.

I just got to the scene where John Browdie is introduced. Good to know I should not try and struggle too much in figuring out what he says.

Peter,

Peter,You asked what Squeers might have meant by Nickleby being some sort of asset to them. I'm not sure, but I'm guessing it has something to do with Ralph. All roads lead to Ralph.

As if the point wasn't already made, we see in chapter 10 just how surly Ralph is. He makes no effort to hide his contempt for his relatives in their presence, and I'm sure he has his selfish reasons for hooking up Nicholas and Kate with the Squeers and Mantalinis. Also, Ralph is always in a hurry to be somewhere else. Maybe he has somewhere to go; maybe he just can't stand the human race.

Demmit, that's quite the attire the "gentleman husband" is wearing. And, oh my, is he a predator. But how can you take him seriously in that getup. It's only been a few minutes and already I tire of him.

Poor Kate.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Peter,

You asked what Squeers might have meant by Nickleby being some sort of asset to them. I'm not sure, but I'm guessing it has something to do with Ralph. All roads lead to Ralph.

As if the p..."

Xan

You are so right. All roads do lead to Ralph, and all those roads are full of potholes and hazards.

You asked what Squeers might have meant by Nickleby being some sort of asset to them. I'm not sure, but I'm guessing it has something to do with Ralph. All roads lead to Ralph.

As if the p..."

Xan

You are so right. All roads do lead to Ralph, and all those roads are full of potholes and hazards.

As to Mr. Browdie's accent, I am quite relieved to find that I am not the only one who has a hard time understanding it. I try to make sense of it by reading it aloud, but you can imagine that for me, as a non-native speaker, it must even be more of a tricky challenge.

Maybe, people in rural Yorkshire spoke with such a thick accent, and is he not a corndealer's son? Saying that, when I was in Yorkshire, I really had to get used to their tendency to swallow syllables, but the language Dickens gives to Browdie does not really mirror the Yorkshire accent to me. 'Tilda's accent is less obtrusive, but I think that Dickens typically tones down the accent of many of his female characters. By rights, Lizzie Hexam would have had the same accent of her brother and her father, wouldn't she? And Little Nell's English would also have reflected her environment - and not so much the purity of her soul ;-)

Maybe, people in rural Yorkshire spoke with such a thick accent, and is he not a corndealer's son? Saying that, when I was in Yorkshire, I really had to get used to their tendency to swallow syllables, but the language Dickens gives to Browdie does not really mirror the Yorkshire accent to me. 'Tilda's accent is less obtrusive, but I think that Dickens typically tones down the accent of many of his female characters. By rights, Lizzie Hexam would have had the same accent of her brother and her father, wouldn't she? And Little Nell's English would also have reflected her environment - and not so much the purity of her soul ;-)

Tristram wrote: "I really had to get used to their tendency to swallow syllables..."

Tristram wrote: "I really had to get used to their tendency to swallow syllables..."(grin) I like that one. I'm stealing it.

Talking about the Squeers children, one might say that a lot of their viciousness is probably nurture and not exclusively nature. You remember the scene when the Squeers family is sitting at mealtime, and little Squeers tells his father that when he runs the school one day, he will also beat up the boys to a T - and how both parents, especially the father, beam with pride? It is clear that a child, being brought up in that way, will automatically think that there is really nothing unusual or even blameworthy about running a school that way. Apart from that, children, up to a certain age, do think their parents know best and can always come up with the right answers to all questions of life. Wackford junior will also have no other children to spend his time with, and that's why his parents' example is the only role model he gets.

As to Fanny, it's the same thing. Add to this that she is also quite ugly and that the marriage market in rural areas is - as you said - not over-encouraging, and you will have an explanation for her bitterness and spite: After all, her friend is four years younger and engaged to be married, whereas she, a schoolmaster's daughter, is still single. Of course, she will look on Nicholas, her father's employee, as her conquest by rights. And yet, for all that I can hardly feel sorry for her because she is so spiteful.

As to Fanny, it's the same thing. Add to this that she is also quite ugly and that the marriage market in rural areas is - as you said - not over-encouraging, and you will have an explanation for her bitterness and spite: After all, her friend is four years younger and engaged to be married, whereas she, a schoolmaster's daughter, is still single. Of course, she will look on Nicholas, her father's employee, as her conquest by rights. And yet, for all that I can hardly feel sorry for her because she is so spiteful.

Alissa wrote: "I also wonder if Noggs is analogous to the Genius of Despair and Suicide, since both have a "cadaverous face" (a unique descriptor). Noggs has already served as a ghost-like intermediary to Nichola..."

Alissa wrote: "I also wonder if Noggs is analogous to the Genius of Despair and Suicide, since both have a "cadaverous face" (a unique descriptor). Noggs has already served as a ghost-like intermediary to Nichola..."Your assessment, Alissa, has made me feel as though getting through those two stories may not have been a complete waste of time! Still, I didn't care for them in Pickwick, and I care for them even less in Nickleby. This novel seems, so far, to have much more of a plot than did Pickwick, and the tales are even more of a jolt and a distraction.

I'm still a week behind in my reading, and have just finished chapter ten. You all seem to have covered everything well - particularly Peter, whose summaries are wonderful, as always. In the Fagin v. Squeers debate, I'm fully with Fagin. I find it hard to hear myself saying this, but at least he offered decent meals, a sense of belonging, and a "skill" - albeit an illegal, immoral one. But I think the greatest villains in all of this are the parents (or, most likely, guardians) of the boys, who are willing to let their children suffer God knows what, just so they don't have to be bothered. Despicable.

A little anecdote about libraries. I happened upon an old flyer -- I wish I still had it; I think it was from the 40s or 50s -- that gave information about "membership" in our county library. My jaw dropped when I read that at one time, you not only had to be a county resident "of good moral character" to get a card, but also had to provide personal references and be sponsored by an existing member. And the rules of the library were strict and non-negotiable. A far cry from guy cutting his toenails at one of our tables (I kid you not!) or the heroin addicts we find passed out in the bathrooms on a regular basis (again - not an exaggeration, unfortunately).

Mary Lou wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I also wonder if Noggs is analogous to the Genius of Despair and Suicide, since both have a "cadaverous face" (a unique descriptor). Noggs has already served as a ghost-like intermed..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I also wonder if Noggs is analogous to the Genius of Despair and Suicide, since both have a "cadaverous face" (a unique descriptor). Noggs has already served as a ghost-like intermed..."I wonder what they thought people of poor moral character were going to do with the books? Other than cut toenails in their proximity, I guess. Sorry about that, Mary Lou--ugh.

You'd be shocked and disgusted, Julie, if you knew what goes on in an urban library. If my boss was able to transfer to one of our small town branches, I'd follow her in a heartbeat.

You'd be shocked and disgusted, Julie, if you knew what goes on in an urban library. If my boss was able to transfer to one of our small town branches, I'd follow her in a heartbeat.

Luckily, our city library is generally acknowledged as a no-toenail-cutting-area ;-) I'm not there very often, because I prefer owning the books I read - but I sometimes accompany my son to the library, and then I also always find something interesting.

Luckily, they never asked if I am "of good moral character" because that would have started me off on all my merits ;-)

Luckily, they never asked if I am "of good moral character" because that would have started me off on all my merits ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Peter, that's a lot of intriguing questions you are asking here, and I thank you very much for all the effort and care you put into your recaps. I will concentrate on Chapter 6 first because the in..."

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

In the following number there was a difficulty which it was marvelous should not oftener have occurred to him in this form of publication. "I could not write a line till three o'clock," he says, describing the close of that number, "and have yet five slips to finish, and don't know what to put in them, for I have reached the point I meant to leave off with." He found easy remedy for such a miscalculation at his outset, and it was nearly his last as well as first misadventure of the kind: his difficulty in Pickwick, as he once told me, having always been, not the running short, but the running over: not the whip, but the drag, that was wanted. The stories filled those slips.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

In the following number there was a difficulty which it was marvelous should not oftener have occurred to him in this form of publication. "I could not write a line till three o'clock," he says, describing the close of that number, "and have yet five slips to finish, and don't know what to put in them, for I have reached the point I meant to leave off with." He found easy remedy for such a miscalculation at his outset, and it was nearly his last as well as first misadventure of the kind: his difficulty in Pickwick, as he once told me, having always been, not the running short, but the running over: not the whip, but the drag, that was wanted. The stories filled those slips.

Mary Lou wrote: "You'd be shocked and disgusted, Julie, if you knew what goes on in an urban library. If my boss was able to transfer to one of our small town branches, I'd follow her in a heartbeat."

Mary Lou wrote: "You'd be shocked and disgusted, Julie, if you knew what goes on in an urban library. If my boss was able to transfer to one of our small town branches, I'd follow her in a heartbeat."Unfortunately I know how you feel, Mary Lou. I had been taking my kids to the nice, new, big library 3 miles away from us because there are just so many more books to browse. I will not go into any details, but because there have been ongoing issues with unsavory characters frequenting the library, we stopped going to that branch. We now go to the branch closest to our house, but since it is very small, many of the books that we know we want I have to put holds on them and have them sent to our branch. It's a small price to pay, though, to not have to worry about my kids while they are browsing through the stacks.

The Five Sisters of York

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘It was a bright and sunny morning in the pleasant time of summer, when one of those black monks emerged from the abbey portal, and bent his steps towards the house of the fair sisters. Heaven above was blue, and earth beneath was green; the river glistened like a path of diamonds in the sun; the birds poured forth their songs from the shady trees; the lark soared high above the waving corn; and the deep buzz of insects filled the air. Everything looked gay and smiling; but the holy man walked gloomily on, with his eyes bent upon the ground. The beauty of the earth is but a breath, and man is but a shadow. What sympathy should a holy preacher have with either?

‘With eyes bent upon the ground, then, or only raised enough to prevent his stumbling over such obstacles as lay in his way, the religious man moved slowly forward until he reached a small postern in the wall of the sisters’ orchard, through which he passed, closing it behind him. The noise of soft voices in conversation, and of merry laughter, fell upon his ears ere he had advanced many paces; and raising his eyes higher than was his humble wont, he descried, at no great distance, the five sisters seated on the grass, with Alice in the centre: all busily plying their customary task of embroidering.

‘“Save you, fair daughters!” said the friar; and fair in truth they were. Even a monk might have loved them as choice masterpieces of his Maker’s hand.

‘The sisters saluted the holy man with becoming reverence, and the eldest motioned him to a mossy seat beside them. But the good friar shook his head, and bumped himself down on a very hard stone,—at which, no doubt, approving angels were gratified.

‘“Ye were merry, daughters,” said the monk.

‘“You know how light of heart sweet Alice is,” replied the eldest sister, passing her fingers through the tresses of the smiling girl.

‘“And what joy and cheerfulness it wakes up within us, to see all nature beaming in brightness and sunshine, father,” added Alice, blushing beneath the stern look of the recluse.

‘The monk answered not, save by a grave inclination of the head, and the sisters pursued their task in silence.

‘“Still wasting the precious hours,” said the monk at length, turning to the eldest sister as he spoke, “still wasting the precious hours on this vain trifling. Alas, alas! that the few bubbles on the surface of eternity—all that Heaven wills we should see of that dark deep stream—should be so lightly scattered!”

‘“Father,” urged the maiden, pausing, as did each of the others, in her busy task, “we have prayed at matins, our daily alms have been distributed at the gate, the sick peasants have been tended,—all our morning tasks have been performed. I hope our occupation is a blameless one?’

‘“See here,” said the friar, taking the frame from her hand, “an intricate winding of gaudy colours, without purpose or object, unless it be that one day it is destined for some vain ornament, to minister to the pride of your frail and giddy sex. Day after day has been employed upon this senseless task, and yet it is not half accomplished. The shade of each departed day falls upon our graves, and the worm exults as he beholds it, to know that we are hastening thither. Daughters, is there no better way to pass the fleeting hours?”

‘The four elder sisters cast down their eyes as if abashed by the holy man’s reproof, but Alice raised hers, and bent them mildly on the friar.

‘“Our dear mother,” said the maiden; “Heaven rest her soul!”

‘“Amen!” cried the friar in a deep voice.

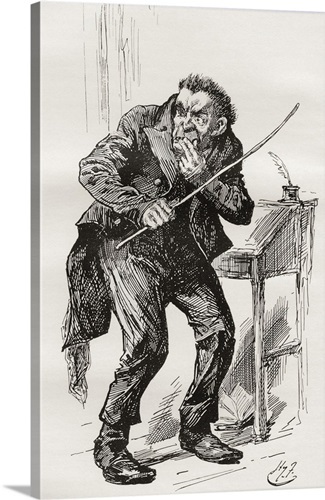

On the opposite side of the fire, there sat with folded arms a wrinkling hideous figure

Chapter 6

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘“I’ll smoke a last pipe,” said the baron, “and then I’ll be off.” So, putting the knife upon the table till he wanted it, and tossing off a goodly measure of wine, the Lord of Grogzwig threw himself back in his chair, stretched his legs out before the fire, and puffed away.

‘He thought about a great many things—about his present troubles and past days of bachelorship, and about the Lincoln greens, long since dispersed up and down the country, no one knew whither: with the exception of two who had been unfortunately beheaded, and four who had killed themselves with drinking. His mind was running upon bears and boars, when, in the process of draining his glass to the bottom, he raised his eyes, and saw, for the first time and with unbounded astonishment, that he was not alone.

‘No, he was not; for, on the opposite side of the fire, there sat with folded arms a wrinkled hideous figure, with deeply sunk and bloodshot eyes, and an immensely long cadaverous face, shadowed by jagged and matted locks of coarse black hair. He wore a kind of tunic of a dull bluish colour, which, the baron observed, on regarding it attentively, was clasped or ornamented down the front with coffin handles. His legs, too, were encased in coffin plates as though in armour; and over his left shoulder he wore a short dusky cloak, which seemed made of a remnant of some pall. He took no notice of the baron, but was intently eyeing the fire.

‘“Halloa!” said the baron, stamping his foot to attract attention.

‘“Halloa!” replied the stranger, moving his eyes towards the baron, but not his face or himself “What now?”

‘“What now!” replied the baron, nothing daunted by his hollow voice and lustreless eyes. “I should ask that question. How did you get here?”

‘“Through the door,” replied the figure.

‘“What are you?” says the baron.

‘“A man,” replied the figure.

‘“I don’t believe it,” says the baron.

‘“Disbelieve it then,” says the figure.

‘“I will,” rejoined the baron.

‘The figure looked at the bold Baron of Grogzwig for some time, and then said familiarly,

‘“There’s no coming over you, I see. I’m not a man!”

‘“What are you then?” asked the baron.

‘“A genius,” replied the figure.

‘“You don’t look much like one,” returned the baron scornfully.

‘“I am the Genius of Despair and Suicide,” said the apparition. “Now you know me.”

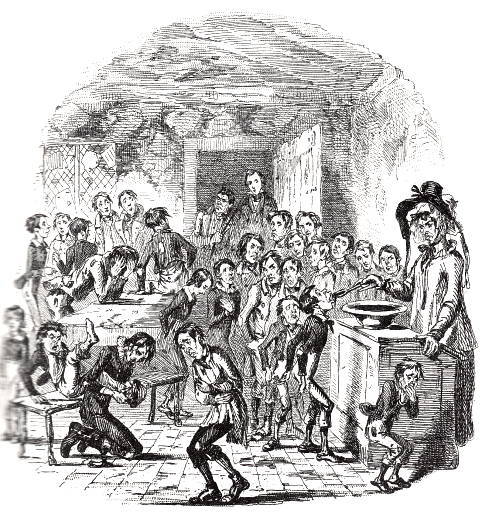

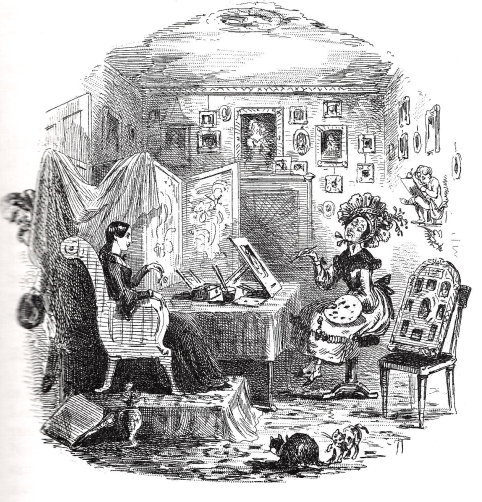

The Internal Economy of Dotheboys Hall

Chapter 8

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was such a crowded scene, and there were so many objects to attract attention, that, at first, Nicholas stared about him, really without seeing anything at all. By degrees, however, the place resolved itself into a bare and dirty room, with a couple of windows, whereof a tenth part might be of glass, the remainder being stopped up with old copy-books and paper. There were a couple of long old rickety desks, cut and notched, and inked, and damaged, in every possible way; two or three forms; a detached desk for Squeers; and another for his assistant. The ceiling was supported, like that of a barn, by cross-beams and rafters; and the walls were so stained and discoloured, that it was impossible to tell whether they had ever been touched with paint or whitewash.

But the pupils—the young noblemen! How the last faint traces of hope, the remotest glimmering of any good to be derived from his efforts in this den, faded from the mind of Nicholas as he looked in dismay around! Pale and haggard faces, lank and bony figures, children with the countenances of old men, deformities with irons upon their limbs, boys of stunted growth, and others whose long meagre legs would hardly bear their stooping bodies, all crowded on the view together; there were the bleared eye, the hare-lip, the crooked foot, and every ugliness or distortion that told of unnatural aversion conceived by parents for their offspring, or of young lives which, from the earliest dawn of infancy, had been one horrible endurance of cruelty and neglect. There were little faces which should have been handsome, darkened with the scowl of sullen, dogged suffering; there was childhood with the light of its eye quenched, its beauty gone, and its helplessness alone remaining; there were vicious-faced boys, brooding, with leaden eyes, like malefactors in a jail; and there were young creatures on whom the sins of their frail parents had descended, weeping even for the mercenary nurses they had known, and lonesome even in their loneliness. With every kindly sympathy and affection blasted in its birth, with every young and healthy feeling flogged and starved down, with every revengeful passion that can fester in swollen hearts, eating its evil way to their core in silence, what an incipient Hell was breeding here!

And yet this scene, painful as it was, had its grotesque features, which, in a less interested observer than Nicholas, might have provoked a smile. Mrs. Squeers stood at one of the desks, presiding over an immense basin of brimstone and treacle, of which delicious compound she administered a large instalment to each boy in succession: using for the purpose a common wooden spoon, which might have been originally manufactured for some gigantic top, and which widened every young gentleman’s mouth considerably: they being all obliged, under heavy corporal penalties, to take in the whole of the bowl at a gasp. In another corner, huddled together for companionship, were the little boys who had arrived on the preceding night, three of them in very large leather breeches, and two in old trousers, a something tighter fit than drawers are usually worn; at no great distance from these was seated the juvenile son and heir of Mr Squeers—a striking likeness of his father—kicking, with great vigour, under the hands of Smike, who was fitting upon him a pair of new boots that bore a most suspicious resemblance to those which the least of the little boys had worn on the journey down—as the little boy himself seemed to think, for he was regarding the appropriation with a look of most rueful amazement. Besides these, there was a long row of boys waiting, with countenances of no pleasant anticipation, to be treacled; and another file, who had just escaped from the infliction, making a variety of wry mouths indicative of anything but satisfaction. The whole were attired in such motley, ill-assorted, extraordinary garments, as would have been irresistibly ridiculous, but for the foul appearance of dirt, disorder, and disease, with which they were associated.

‘Now,’ said Squeers, giving the desk a great rap with his cane, which made half the little boys nearly jump out of their boots, ‘is that physicking over?’

‘Just over,’ said Mrs. Squeers, choking the last boy in her hurry, and tapping the crown of his head with the wooden spoon to restore him. ‘Here, you Smike; take away now. Look sharp!’

Detail:

Commentary:

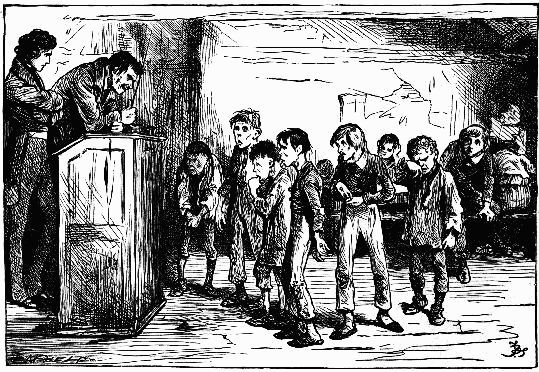

Despite the general weakness of the Nickleby plates, occasionally Browne shows evidence of having learned how to provide graphic continuity to sequences of plates stretched over more than a single part, in a novel whose action, however stilted, is less thoroughly episodic than Pickwick's. Thus, in Parts III and IV he must illustrate two related strands of the story, in a sequence which might be described as al-bl-b2-a2. The first and fourth, "The internal economy of Dotheboys Hall" (ch. 8) and "Nicholas astonishes Mr. Squeers and family" (ch. 13), feature the same characters in exactly the same setting; the two sandwiched between, "Kate Nickleby sitting to Miss La Creevy" (ch. 10), and "Newman Noggs leaves the ladies in the empty house" (ch. 11), both center on Kate's London adventures while Nicholas is in Yorkshire. In addition to the connections between the members of the pair in each part, there are also links between each two adjacent etchings in the series of four, and the first and fourth plates have causal links as well.

The two Dotheboys Halls plates form a before-and-after sequence: in the first, Phiz challenges Cruikshank as an artist of the grotesquely pitiable, attempting something in the vein of "Oliver asks for more." It has been remarked that Dickens' text is superior to Phiz's etching, about which it seems difficult to say, as John Forster did about the text, that "Dotheboys was, like a piece by Hogarth, both ludicrous and terrible'" (Hunt, p. 134). Such a comparison seems too dismissive, but to contrast Browne with Cruikshank does reveal something about the former's virtues and limitations. For Browne does not achieve, with his ragged, starving boys, anything like the preternatural effect of Cruikshank's workhouse lads who have been reduced to a subhuman level, with their stupefied expressions and sunken eyes, and even the bony structure of their faces and the shapes of their cropped heads. By contrast, Browne's are still recognizably boys, but boys with melodramatic faces either virtuous and horrified or wizened and grotesque.

Well, that's a great illustration of despair. Poor guy. He could also pass for a down and out vampire. The baron on the other hand looks like a buffoon, which he is not.

Well, that's a great illustration of despair. Poor guy. He could also pass for a down and out vampire. The baron on the other hand looks like a buffoon, which he is not.

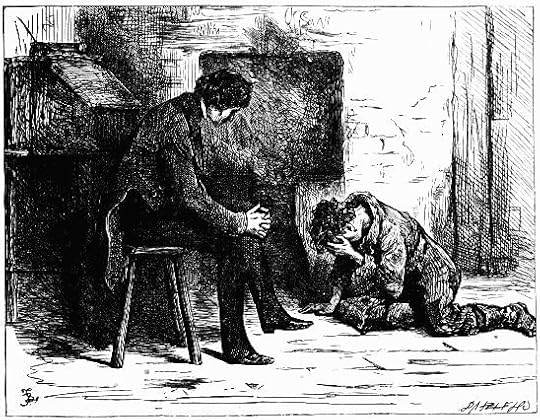

"Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder.

Chapter 8

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Text Illustrated:

"You need not fear me," said Nicholas kindly. "Are you cold?"

"N-n-o."

"You are shivering."

"I am not cold," replied Smike quickly. "I am used to it."

There was such an obvious fear of giving offence in his manner, and he was such a timid, broken-spirited creature, that Nicholas could not help exclaiming, "Poor fellow!"

If he had struck the drudge, he would have slunk away without a word. But, now, he burst into tears.

"Oh dear, oh dear!" he cried, covering his face with his cracked and horny hands. "My heart will break. It will, it will."

"Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. "Be a man; you are nearly one by years, God help you."

"By years!" cried Smike. "Oh dear, dear, how many of them! How many of them since I was a little child, younger than any that are here now! Where are they all!"

"Whom do you speak of?" inquired Nicholas, wishing to rouse the poor half-witted creature to reason. "Tell me."

"My friends," he replied, "myself — my — oh! what sufferings mine have been!"

"There is always hope," said Nicholas; he knew not what to say. — Volume 1, Chapter 8, "Of the Internal Economy of Dotheboys Hall,"

Commentary:

The passage from the closing of Chapter 8 of 1861 edition of Nicholas Nickleby, first published in Part Three (June 1838), comes the end of an extremely trying day for the protagonist at the Yorkshire school run by the brutal, greedy, mean-spirited Wackford Squeers, the one-eyed sadist consistently depicted by illustrators from Phiz to Harold Copping. Rather than display Nicholas's pity for the distraught, mentally-challenged Smike, Phiz focusses on the difficult circumstances that all the students at "Do-the-boys" Hall must endure in The Internal Economy of Dotheboys Hall earlier in this serial installment. Under Phiz's caricatural interpretation, all the other boys are as gaunt, ragged, and dispirited as Smike, not introduced as an individual until the illustration for the twenty-second chapter, The Country Manager Rehearses a Combat. Thus, Darley's attitude strikes the present-day reader as modern in that he expresses sympathy for special-needs students such as Smike, and finds admirable Nicholas's sympathy for the distressed adolescent. The sentimental scene between Smike and Nicholas from Chapter 8 is without precedent in the original serial (April 1838-October 1839).

Independent of Darley's choices of subjects for the frontispieces of the three volumes of Nicholas Nickleby, Fred Barnard elected to provide a more realistic but less tender version of the same scene in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, with Nicholas seated, hearing Sikes's anguished narrativce about his dead friend and his dismal outlook if he remains Dotheboys Hall: "Pain and fear, pain and fear, alive or dead. No hope, no hope!" — Chap. viii. Whereas Phiz's approach was to render Nicholas a typical Dickens-Scott young man in search of himself in the picaresque tradition, Barnard made Nicholas something of an individual, but, even though he makes Smike a very real youth, Nicholas's comforting him in the Darley plate renders him more worthy of the reader's sympathy. What little we see of Smike here reveals that Darley elected not to be guided by the long-headed, perpetually astounded caricature consistently delivered by Phiz in the original sequence.

Darley's background detailing situates this emotional scene in the mundane realities of the schoolroom; there is nothing noble or traditional about the cast-iron stove in the set, but it is undoubtedly functional, and probably represents the kind of heating system American schools would have had at the time. Moreover, the details in the background reveal that Darley had carefully studied the text of the eighth chapter (which, in this American edition, bears its original title, "Of the Internal Economy of Dotheboys Hall"). For example, in the frontispiece, the window behind and above Nicholas appears to be stuffed with paper and books, just as in

a couple of windows, whereof a tenth part might be of glass, the remainder being stopped up with old copy-books and paper.

The cast-iron stove and chimney are also derived directly from the text:

There was a small stove at that corner of the room which was nearest to the master's desk, and by it Nicholas sat down, so depressed and self-degraded by the consciousness of his position, that if death could have come upon him at that time, he would have been almost happy to meet it.

Playing the role of Cinderella in this anti-fairy tale, Smike is the boy expected to tend the stove; hence, Darley shows its door open, and paper beside Smike intended to facilitate lighting the fire, there being tongs immediately beside the lad:

[Nicholas] all at once encountered the upturned face of Smike, who was on his knees before the stove, picking a few stray cinders from the hearth and planting them on the fire. He had paused to steal a look at Nicholas, and when he saw that he was observed, shrunk back, as if expecting a blow.

Darley has even covered the boards underneath the stove with a fireproof material, and has the stove sitting on a platform to further insulate it. The master's desk, stool, and wastebasket complete the scene's realia. The reader, attending to the meaning of details that he or she will not encounter for 150 pages, quickly assimilates these details as he or she attempts a proleptic reading to assess the emotional significance of the characters' juxtapositions and postures, which contribute to the binary opposites upon which Darley has structured the scene. Nicholas, not merely warmly but fashionably dressed, sits on a chair, comforting Smile, clad in the merest rags, kneeling before the stove. The cracked plaster, revealing the lath beneath, implies the rundown condition of the schoolroom, and Squeers' wilfull neglect of the physical condition of the school in general. Amidst these details sits the well-dressed, reasonable Nicholas, who simply does not fit this environment.

The first class English spelling and philosophy

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

After some half-hour’s delay, Mr. Squeers reappeared, and the boys took their places and their books, of which latter commodity the average might be about one to eight learners. A few minutes having elapsed, during which Mr. Squeers looked very profound, as if he had a perfect apprehension of what was inside all the books, and could say every word of their contents by heart if he only chose to take the trouble, that gentleman called up the first class.

Obedient to this summons there ranged themselves in front of the schoolmaster’s desk, half-a-dozen scarecrows, out at knees and elbows, one of whom placed a torn and filthy book beneath his learned eye.

‘This is the first class in English spelling and philosophy, Nickleby,’ said Squeers, beckoning Nicholas to stand beside him. ‘We’ll get up a Latin one, and hand that over to you. Now, then, where’s the first boy?’

‘Please, sir, he’s cleaning the back-parlour window,’ said the temporary head of the philosophical class.

‘So he is, to be sure,’ rejoined Squeers. ‘We go upon the practical mode of teaching, Nickleby; the regular education system. C-l-e-a-n, clean, verb active, to make bright, to scour. W-i-n, win, d-e-r, der, winder, a casement. When the boy knows this out of book, he goes and does it. It’s just the same principle as the use of the globes. Where’s the second boy?’

‘Please, sir, he’s weeding the garden,’ replied a small voice.

‘To be sure,’ said Squeers, by no means disconcerted. ‘So he is. B-o-t, bot, t-i-n, tin, bottin, n-e-y, ney, bottinney, noun substantive, a knowledge of plants. When he has learned that bottinney means a knowledge of plants, he goes and knows ‘em. That’s our system, Nickleby: what do you think of it?’

‘It’s very useful one, at any rate,’ answered Nicholas.

"Pain and fear, pain and fear for me, alive or dead. No hope, no hope!"

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

As he was absorbed in these meditations, he all at once encountered the upturned face of Smike, who was on his knees before the stove, picking a few stray cinders from the hearth and planting them on the fire. He had paused to steal a look at Nicholas, and when he saw that he was observed, shrunk back, as if expecting a blow.

‘You need not fear me,’ said Nicholas kindly. ‘Are you cold?’

‘N-n-o.’

‘You are shivering.’

‘I am not cold,’ replied Smike quickly. ‘I am used to it.’

There was such an obvious fear of giving offence in his manner, and he was such a timid, broken-spirited creature, that Nicholas could not help exclaiming, ‘Poor fellow!’

If he had struck the drudge, he would have slunk away without a word. But, now, he burst into tears.

‘Oh dear, oh dear!’ he cried, covering his face with his cracked and horny hands. ‘My heart will break. It will, it will.’

‘Hush!’ said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. ‘Be a man; you are nearly one by years, God help you.’

‘By years!’ cried Smike. ‘Oh dear, dear, how many of them! How many of them since I was a little child, younger than any that are here now! Where are they all!’

‘Whom do you speak of?’ inquired Nicholas, wishing to rouse the poor half-witted creature to reason. ‘Tell me.’

‘My friends,’ he replied, ‘myself—my—oh! what sufferings mine have been!’

‘There is always hope,’ said Nicholas; he knew not what to say.

‘No,’ rejoined the other, ‘no; none for me. Do you remember the boy that died here?’

‘I was not here, you know,’ said Nicholas gently; ‘but what of him?’

‘Why,’ replied the youth, drawing closer to his questioner’s side, ‘I was with him at night, and when it was all silent he cried no more for friends he wished to come and sit with him, but began to see faces round his bed that came from home; he said they smiled, and talked to him; and he died at last lifting his head to kiss them. Do you hear?’

‘Yes, yes,’ rejoined Nicholas.

‘What faces will smile on me when I die!’ cried his companion, shivering. ‘Who will talk to me in those long nights! They cannot come from home; they would frighten me, if they did, for I don’t know what it is, and shouldn’t know them. Pain and fear, pain and fear for me, alive or dead. No hope, no hope!’

The bell rang to bed: and the boy, subsiding at the sound into his usual listless state, crept away as if anxious to avoid notice. It was with a heavy heart that Nicholas soon afterwards—no, not retired; there was no retirement there—followed—to his dirty and crowded dormitory.

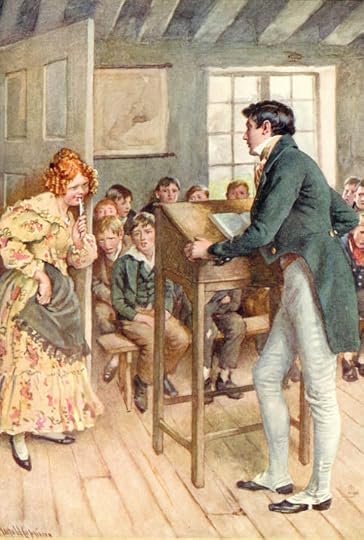

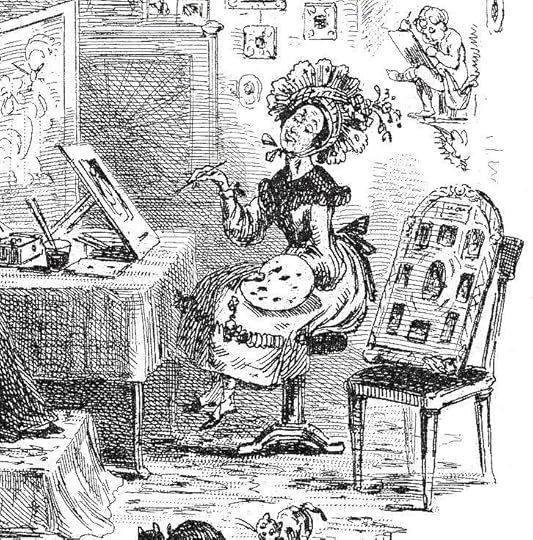

"Oh! as soft as possible if you please"

Chapter 9

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Miss Fanny Squeers carefully treasured up this, and much more conversation on the same subject, until she retired for the night, when she questioned the hungry servant, minutely, regarding the outward appearance and demeanour of Nicholas; to which queries the girl returned such enthusiastic replies, coupled with so many laudatory remarks touching his beautiful dark eyes, and his sweet smile, and his straight legs—upon which last-named articles she laid particular stress; the general run of legs at Dotheboys Hall being crooked—that Miss Squeers was not long in arriving at the conclusion that the new usher must be a very remarkable person, or, as she herself significantly phrased it, ‘something quite out of the common.’ And so Miss Squeers made up her mind that she would take a personal observation of Nicholas the very next day.

In pursuance of this design, the young lady watched the opportunity of her mother being engaged, and her father absent, and went accidentally into the schoolroom to get a pen mended: where, seeing nobody but Nicholas presiding over the boys, she blushed very deeply, and exhibited great confusion.

‘I beg your pardon,’ faltered Miss Squeers; ‘I thought my father was—or might be—dear me, how very awkward!’

‘Mr. Squeers is out,’ said Nicholas, by no means overcome by the apparition, unexpected though it was.

‘Do you know will he be long, sir?’ asked Miss Squeers, with bashful hesitation.

‘He said about an hour,’ replied Nicholas—politely of course, but without any indication of being stricken to the heart by Miss Squeers’s charms.

‘I never knew anything happen so cross,’ exclaimed the young lady. ‘Thank you! I am very sorry I intruded, I am sure. If I hadn’t thought my father was here, I wouldn’t upon any account have—it is very provoking—must look so very strange,’ murmured Miss Squeers, blushing once more, and glancing, from the pen in her hand, to Nicholas at his desk, and back again.

‘If that is all you want,’ said Nicholas, pointing to the pen, and smiling, in spite of himself, at the affected embarrassment of the schoolmaster’s daughter, ‘perhaps I can supply his place.’

Miss Squeers glanced at the door, as if dubious of the propriety of advancing any nearer to an utter stranger; then round the schoolroom, as though in some measure reassured by the presence of forty boys; and finally sidled up to Nicholas and delivered the pen into his hand, with a most winning mixture of reserve and condescension.

‘Shall it be a hard or a soft nib?’ inquired Nicholas, smiling to prevent himself from laughing outright.

‘He has a beautiful smile,’ thought Miss Squeers.

‘Which did you say?’ asked Nicholas.

‘Dear me, I was thinking of something else for the moment, I declare,’ replied Miss Squeers. ‘Oh! as soft as possible, if you please.’ With which words, Miss Squeers sighed. It might be, to give Nicholas to understand that her heart was soft, and that the pen was wanted to match.

Fanny Squeers and Nicholas Nickleby

Chapter 9

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

Although Copping could have easily chosen to focus on Dickens's social criticism in Nicholas Nickleby, he chose to focus on the memorable characters themselves, in comedic situations. On Nicholas's first full day as a fledgling teacher or "usher" at Wackford Squeers's "Dotheboys Hall," the protagonist encounters his employer's daughter, the awkward and ugly Fanny, who has popped into his classroom, ostensibly to have her father mend a pen, but in fact to see for herself the handsome youth about whom her parents and brother had been talking when she arrived home the previous night. Having ascertained from a perpetually hungry maid-servant that Nicolas has a fine form and handsome face, Fanny has determined to find out for herself at the first opportunity:

The young lady watched the opportunity of her mother being engaged, and her father absent, and went accidentally into the school-room to get a pen mended: where, seeing nobody but Nicholas presiding over the boys, she blushed very deeply, and exhibited great confusion.

". . .I am very sorry I intruded, I am sure. If I hadn't thought my father was here, I wouldn't upon any account have — it is very provoking — must look so very strange," murmured Miss Squeers, blushing once more, and glancing, from the pen in her hand, to Nicholas at his desk, and back again.

Copping has transformed the "desk" mentioned in Dickens into a podium to focus on the principals, thereby shortening the distance between the speakers. Nicholas's snow-white "stirrup pants," very much in vogue in the late 1830s, suggest his innocence and display his youthful figure to advantage. Fanny's buck-teeth, on the other hand, seem to be Copping's invention, for Dickens just a few pages earlier in chapter 9, "Of Miss Squeers, Mrs. Squeers, Master Squeers, and Mr. Squeers; and of various Matters and Persons connected no less with the Squeerses than with Nicholas Nickleby" (installment 3, June 1838), describes her merely as short like her father, with her mother's harsh voice and her father's "remarkable expression of the right eye, something akin to having none at all." Phiz does not in fact describe her, so that Copping has been free to improvise, providing her with a fashionable gown and apron, and ringlets in the late Regency mode. Copping connects the figures by repeating the color of the apron in the boy's jacket and vest (left of center) and in Nicholas's swallow-tail coat. The gold of Fanny's hair is repeated in Nicholas's waist-coat. Although these items of dress are consistent with Phiz's original illustrations (for example, "Nicholas Hints at the Probability of His Leaving the Company," chapter 29), Copping has individualized Nicholas's profile.

Kate Nickleby Sitting to Miss La Creevy

Chapter 10

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

As she ceased to speak, there was a rustling behind the screen which stood between her and the door, and some person knocked at the wainscot.’

‘Come in, whoever it is!’ cried Miss La Creevy.

The person complied, and, coming forward at once, gave to view the form and features of no less an individual than Mr. Ralph Nickleby himself.

‘Your servant, ladies,’ said Ralph, looking sharply at them by turns. ‘You were talking so loud, that I was unable to make you hear.’

When the man of business had a more than commonly vicious snarl lurking at his heart, he had a trick of almost concealing his eyes under their thick and protruding brows, for an instant, and then displaying them in their full keenness. As he did so now, and tried to keep down the smile which parted his thin compressed lips, and puckered up the bad lines about his mouth, they both felt certain that some part, if not the whole, of their recent conversation, had been overheard.

‘I called in, on my way upstairs, more than half expecting to find you here,’ said Ralph, addressing his niece, and looking contemptuously at the portrait. ‘Is that my niece’s portrait, ma’am?’

‘Yes it is, Mr. Nickleby,’ said Miss La Creevy, with a very sprightly air, ‘and between you and me and the post, sir, it will be a very nice portrait too, though I say it who am the painter.’

‘Don’t trouble yourself to show it to me, ma’am,’ cried Ralph, moving away, ‘I have no eye for likenesses. Is it nearly finished?’

‘Why, yes,’ replied Miss La Creevy, considering with the pencil end of her brush in her mouth. ‘Two sittings more will—’

‘Have them at once, ma’am,’ said Ralph. ‘She’ll have no time to idle over fooleries after tomorrow. Work, ma’am, work; we must all work. Have you let your lodgings, ma’am?’

‘I have not put a bill up yet, sir.’

‘Put it up at once, ma’am; they won’t want the rooms after this week, or if they do, can’t pay for them. Now, my dear, if you’re ready, we’ll lose no more time.’

Detail of Miss LaCreevy:

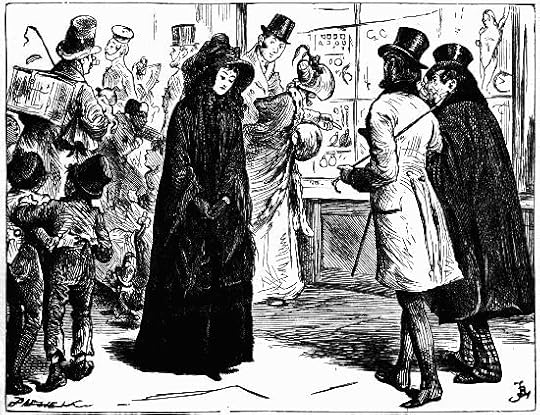

Kate walked sadly back to their lodgings in the Strand

chapter 10

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘If you’re ready to come,’ said Madame Mantalini, ‘you had better begin on Monday morning at nine exactly, and Miss Knag the forewoman shall then have directions to try you with some easy work at first. Is there anything more, Mr. Nickleby?’

‘Nothing more, ma’am,’ replied Ralph, rising.

‘Then I believe that’s all,’ said the lady. Having arrived at this natural conclusion, she looked at the door, as if she wished to be gone, but hesitated notwithstanding, as though unwilling to leave to Mr. Mantalini the sole honour of showing them downstairs. Ralph relieved her from her perplexity by taking his departure without delay: Madame Mantalini making many gracious inquiries why he never came to see them; and Mr. Mantalini anathematising the stairs with great volubility as he followed them down, in the hope of inducing Kate to look round,—a hope, however, which was destined to remain ungratified.

‘There!’ said Ralph when they got into the street; ‘now you’re provided for.’

Kate was about to thank him again, but he stopped her.

‘I had some idea,’ he said, ‘of providing for your mother in a pleasant part of the country—(he had a presentation to some almshouses on the borders of Cornwall, which had occurred to him more than once)—but as you want to be together, I must do something else for her. She has a little money?’

‘A very little,’ replied Kate.

‘A little will go a long way if it’s used sparingly,’ said Ralph. ‘She must see how long she can make it last, living rent free. You leave your lodgings on Saturday?’

‘You told us to do so, uncle.’

‘Yes; there is a house empty that belongs to me, which I can put you into till it is let, and then, if nothing else turns up, perhaps I shall have another. You must live there.’

‘Is it far from here, sir?’ inquired Kate.

‘Pretty well,’ said Ralph; ‘in another quarter of the town—at the East end; but I’ll send my clerk down to you, at five o’clock on Saturday, to take you there. Goodbye. You know your way? Straight on.’

Coldly shaking his niece’s hand, Ralph left her at the top of Regent Street, and turned down a by-thoroughfare, intent on schemes of money-getting. Kate walked sadly back to their lodgings in the Strand.

I can't find who this artist is. Yet.

Text Illustrated:

It was such a crowded scene, and there were so many objects to attract attention, that, at first, Nicholas stared about him, really without seeing anything at all. By degrees, however, the place resolved itself into a bare and dirty room, with a couple of windows, whereof a tenth part might be of glass, the remainder being stopped up with old copy-books and paper. There were a couple of long old rickety desks, cut and notched, and inked, and damaged, in every possible way; two or three forms; a detached desk for Squeers; and another for his assistant. The ceiling was supported, like that of a barn, by cross-beams and rafters; and the walls were so stained and discoloured, that it was impossible to tell whether they had ever been touched with paint or whitewash.

But the pupils—the young noblemen! How the last faint traces of hope, the remotest glimmering of any good to be derived from his efforts in this den, faded from the mind of Nicholas as he looked in dismay around! Pale and haggard faces, lank and bony figures, children with the countenances of old men, deformities with irons upon their limbs, boys of stunted growth, and others whose long meagre legs would hardly bear their stooping bodies, all crowded on the view together; there were the bleared eye, the hare-lip, the crooked foot, and every ugliness or distortion that told of unnatural aversion conceived by parents for their offspring, or of young lives which, from the earliest dawn of infancy, had been one horrible endurance of cruelty and neglect. There were little faces which should have been handsome, darkened with the scowl of sullen, dogged suffering; there was childhood with the light of its eye quenched, its beauty gone, and its helplessness alone remaining; there were vicious-faced boys, brooding, with leaden eyes, like malefactors in a jail; and there were young creatures on whom the sins of their frail parents had descended, weeping even for the mercenary nurses they had known, and lonesome even in their loneliness. With every kindly sympathy and affection blasted in its birth, with every young and healthy feeling flogged and starved down, with every revengeful passion that can fester in swollen hearts, eating its evil way to their core in silence, what an incipient Hell was breeding here!

And yet this scene, painful as it was, had its grotesque features, which, in a less interested observer than Nicholas, might have provoked a smile. Mrs. Squeers stood at one of the desks, presiding over an immense basin of brimstone and treacle, of which delicious compound she administered a large instalment to each boy in succession: using for the purpose a common wooden spoon, which might have been originally manufactured for some gigantic top, and which widened every young gentleman’s mouth considerably: they being all obliged, under heavy corporal penalties, to take in the whole of the bowl at a gasp. In another corner, huddled together for companionship, were the little boys who had arrived on the preceding night, three of them in very large leather breeches, and two in old trousers, a something tighter fit than drawers are usually worn; at no great distance from these was seated the juvenile son and heir of Mr Squeers—a striking likeness of his father—kicking, with great vigour, under the hands of Smike, who was fitting upon him a pair of new boots that bore a most suspicious resemblance to those which the least of the little boys had worn on the journey down—as the little boy himself seemed to think, for he was regarding the appropriation with a look of most rueful amazement. Besides these, there was a long row of boys waiting, with countenances of no pleasant anticipation, to be treacled; and another file, who had just escaped from the infliction, making a variety of wry mouths indicative of anything but satisfaction. The whole were attired in such motley, ill-assorted, extraordinary garments, as would have been irresistibly ridiculous, but for the foul appearance of dirt, disorder, and disease, with which they were associated.

Kim,

It is always good when you post the illustrations because they show us the whole variety of styles and interpretations that can be brought to the Dickens universe. While personally I will always stay a phan of Fiz's or a fan of Phiz's, whose figures always border on caricature (at least in my eyes), there is also a lot to say in favour of Barnard's realism who adds a cutting edge to the misery of Smike and of Dotheboys Hall in general.

When I take a look at Furniss's Squeers, however, I am strongly reminded of a creature out of Tolkien's books.

It is always good when you post the illustrations because they show us the whole variety of styles and interpretations that can be brought to the Dickens universe. While personally I will always stay a phan of Fiz's or a fan of Phiz's, whose figures always border on caricature (at least in my eyes), there is also a lot to say in favour of Barnard's realism who adds a cutting edge to the misery of Smike and of Dotheboys Hall in general.

When I take a look at Furniss's Squeers, however, I am strongly reminded of a creature out of Tolkien's books.

Linda wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "You'd be shocked and disgusted, Julie, if you knew what goes on in an urban library. If my boss was able to transfer to one of our small town branches, I'd follow her in a heartbea..."

It's sad that parents should have to worry about sending their children to a library ...

It's sad that parents should have to worry about sending their children to a library ...

Julie wrote: "Linda, the only thing I do like about Mrs. Squeers is that she calls Nicholas "Knuckleboy." :) "

Julie wrote: "Linda, the only thing I do like about Mrs. Squeers is that she calls Nicholas "Knuckleboy." :) "I agree, it is a funny name. But at the time I read it, it was just the beginning of what I suspected what was to come so I was not very happy with her.

Julie wrote: "Between the 1730s and 1842 the standard annual fee generally amounted to about double the purchase price of a normal three-volume novel of the time..."

Thanks for this information on libraries back in this time, Julie. My family uses our library extensively, and although we generally think of the library as "free", of course we pay taxes that go to maintaining the libraries. A couple of months ago I discovered a transparency tool for our county's property taxes and found out that the amount that my husband and I pay in taxes that go directly to the library system is $147 for the 2018 tax year. I was surprised it was that much when you put a dollar amount on it, but on the other hand we are fortunate to have an excellent library system. I rarely purchase new books, but if we put a figure of ~$20 on a new hardcover book, that would put our per year library "fee" at the cost of just over seven books. It's funny, now that I have that figure of $147 in my head, I think of it every time I go to the library, determined to get my money's worth. :)

I noticed on the link you gave that it limited the amount of time of lending a new book to between 2 and 6 days, but longer for older books. I guess if I lived back in the day I would be forced to wait until books became old as I would never be able to read through a book in a mere 2 days!

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "So, I'm through chapter 8, and I'm comparing Squeers with Fagin, and Fagin is coming out the better. Fagin fed, clothed, and housed his kids better than Squeers."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "So, I'm through chapter 8, and I'm comparing Squeers with Fagin, and Fagin is coming out the better. Fagin fed, clothed, and housed his kids better than Squeers."I agree with your assessment here, Xan. Although I did not read OT with the group I have seen the movie and I don't remember Fagin being such a nasty character that Squeers is. Both Mr. and Mrs. Squeers make me want to do unspeakable things to them and save all those poor children. Plus like you said, Squeers is actually getting paid by the poor children's parents, which makes him even more despicable for his treatment towards the children.

Peter wrote: "That, and, of course, who would want Squeers as a father- in-law?

Peter wrote: "That, and, of course, who would want Squeers as a father- in-law?:-))"

Lol. No thank you. :)

Tristram wrote: "It's sad that parents should have to worry about sending their children to a library ..."

Tristram wrote: "It's sad that parents should have to worry about sending their children to a library ..."Yes, very sad. My library is in a small city. Our branches in the smaller towns don't have these problems. But we've had at least one attempted abduction (a young girl in the bathroom), lots of overdoses (one mom pricked herself when she grabbed a needle her toddler was getting ready to pick up off the floor, and she had to go to the hospital for tests), assaults, sex in the bathrooms, vandalism, and bedbug infestations. Shouting and bad language are daily occurrences. We have a deputy on duty there all the time, which helps minimize the chaos. I wouldn't work there otherwise. Just putting it all in writing makes me wonder why I'm still there, frankly, but it does keep life interesting.

But as I said, our smaller branches are much more pleasant and safe, and I wouldn't hesitate to take my granddaughter there.

I have always thought our library system one of the best and I volunteer in our small used book shop by the Friends of the Library. We are in a suburban area but the downtown Houston Public Library is also very nice and clean although I have only been there a time or two. But, I was amazed by the library in Iowa City that I recently visited with my daughter-in-law and grandchildren. That library put ours to shame but perhaps it is because it is near the U. of Iowa campus. I was impressed.

I have always thought our library system one of the best and I volunteer in our small used book shop by the Friends of the Library. We are in a suburban area but the downtown Houston Public Library is also very nice and clean although I have only been there a time or two. But, I was amazed by the library in Iowa City that I recently visited with my daughter-in-law and grandchildren. That library put ours to shame but perhaps it is because it is near the U. of Iowa campus. I was impressed.

Linda wrote: "Both Mr. and Mrs. Squeers make me want to do unspeakable things to them and save all those poor children."

Yes, Linda, and you'll have me standing next to you, helping you!

Yes, Linda, and you'll have me standing next to you, helping you!

Mary Lou wrote: "and bedbug infestations."

That is actually my nightmare, and the main reason why I hardly ever get books from the library or second-hand books at all. I have no particularly expensive hobbies - like diamond-collecting, sailing, shooting elephants and stuff like that - and that's why I indulge in the pleasure of buying books and films quite a lot.

That is actually my nightmare, and the main reason why I hardly ever get books from the library or second-hand books at all. I have no particularly expensive hobbies - like diamond-collecting, sailing, shooting elephants and stuff like that - and that's why I indulge in the pleasure of buying books and films quite a lot.

Mary Lou wrote: "I'm so glad you don't indulge in shooting elephants!"

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood.

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood.

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "and bedbug infestations."

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "and bedbug infestations."That is actually my nightmare, and the main reason why I hardly ever get books from the library or second-hand books at all."

Oh no. I've never thought of bedbug infestations stemming from used books! Thank you for giving me something new to worry about now.

Linda wrote: "Julie wrote: "Linda, the only thing I do like about Mrs. Squeers is that she calls Nicholas "Knuckleboy." :) "

Linda wrote: "Julie wrote: "Linda, the only thing I do like about Mrs. Squeers is that she calls Nicholas "Knuckleboy." :) "I agree, it is a funny name. But at the time I read it, it was just the beginning of ..."

I haven't looked up what I pay in property taxes for the library, but I've always considered the late fees to be my subscription charge. And there are plenty of those!

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "I'm so glad you don't indulge in shooting elephants!"

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood."

Do you suppose you could sail to wherever it may be that you shoot your elephants after buying a sailboat with the money you'll get once you sell the diamonds you've collected?

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood."

Do you suppose you could sail to wherever it may be that you shoot your elephants after buying a sailboat with the money you'll get once you sell the diamonds you've collected?

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "I'm so glad you don't indulge in shooting elephants!"

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood."

Do you suppose you could sail to wherever it may be that you shoo..."

That puts the whole matter into a completely new light, all those hobbies paying the costs for each other. But still, I'd prefer sitting in my café and reading my books, and from time to time swinging an épée.

It is frowned upon in the neighbourhood."

Do you suppose you could sail to wherever it may be that you shoo..."

That puts the whole matter into a completely new light, all those hobbies paying the costs for each other. But still, I'd prefer sitting in my café and reading my books, and from time to time swinging an épée.

Books mentioned in this topic

Don Quixote (other topics)Don Quixote (other topics)

Squeers and his Hall are based on William Shaw and his Bowes academy. Shaw was sued by p..."

Xan

Thank you for providing the link. The information gives us much depth and analysis into the original Squeers and Dotheboys Hall. I am constantly thankful for all the research that is done on behalf of others. It should be noted that Hablot K. Browne accompanied Dickens on his tour of the northern schools. While I doubt he portrayed any of the people accurately in his illustrations, I’m intrigued when I look at them. He is as close as we can get to a visual peek at the school in the early 1830’s. Dickens, of course, describes it verbally. What a horrid place Shaw presided over.