The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP Chapters 44 - 46

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 45

This is quite the chapter. Who knew that so much character development, plot advancement, humour, and pathos could be packed into so few pages? We will stay within the walls of the Fleet, but that will not limit the scope of our reading. And so first, let us follow Sam after he makes up Mr Pickwick’s room.

The Fleet prison seems large and offers much for the prisoner to enjoy. We find Sam on a bench with a beer in his hand and an old newspaper from which to read the police reports beside him. He sends a platonic wink towards a young lady peeling potatoes. Sam is content. I can’t remember if we have been told before, but it is interesting to note that Sam can read.

Sam’s first visitor of the day is his father who is bursting with joy at the news that Sam’s step-mother and the red-nosed Stiggins have come for a visit. With a wink about Sam not mentioning who Sam’s creditor is, Sam’s father recounts how he brought Stiggins to the jail by giving him the most memorable, bouncy, and horrid coach ride possible. As Weller senior says, “he was a flyin’ out o’ the harmcheer all the way.” What a wonderful way to create the word armchair. The words “harm” and the word “cheer” give a perfect description with meaning. No doubt Weller senior would enjoy causing innocent “harm” to Stiggins. What “cheer” would Weller have enjoyed as Stiggins bounced about. In future I must look more carefully at how Dickens constructs his dialect. What follows is enormous fun. Stiggins attempts to save Sam from his apparent fallen state, but can only do so by finding his own spirit in a bottle. Mrs Weller joins in on the intervention, but does so only after an alcoholic intervention on herself. While this scene is being played out, Mr Weller senior is busy aping and pantomiming the proceedings. Mr Weller sums up the disastrous event by observing “that wot they drink, don’t seem no nourishment to ‘me; it all turns to warm water, and comes pourin’ out o’ their eyes. ‘Pend upon it, Sammy, it’s a consritootional infirmity.” Crocodile tears from too many beers perhaps? Stiggins insists that Sam should, at all costs, avoid intoxication. This conclusion comes, of course, at the height of Stiggins own drunkenness.

Before Mr Weller senior leaves he tells his son that he has a plan to help Mr Pickwick escape. It has to do with stuffing Pickwick into a hollow piano forte and sending it to “Merriker.” The Americans, reasons Mr Weller, will welcome Pickwick’s money. Thus, if Pickwick stays in America until Mrs Bardell dies or Mr Dodson and Fog are hanged, Pickwick will be safe. There is something appealing to this bizarre plan. Weller senior does have a vivid imagination.

Thoughts

The first part of Sam’s day in the Fleet yard is entertaining. From settling in to read a newspaper, to winking at a young lady, to the visit from his father, step mother and Stiggins, Dickens keeps the tone light, humourous, and entertaining. Do you think Dickens overdid the broad humour, or did you find this part of the chapter an enjoyable experience?

Clearly, Dickens has no patience with reverend Stiggins. To what extent did you find Dickens’s characterization of Stiggins believable?

I found the second part of this chapter an abrupt change in tone, focus, and style. Dickens moves us from the broad humour of Sam’s encounters in the first part of the chapter to a much more somber reflection on how the vagrancies of life and the incarceration of an individual can ruin any person. I found the second part of this chapter much like that of Chapter 44 where the cobbler “so like death in life” does die. Dickens creates extremes in emotion and life by changing the mood of Chapter 45 very abruptly. Within a few sentences of Mr Weller leaving Sam, Mr Pickwick and Sam meet Mr Jingle. Through the previous kindness of Pickwick, Jingle’s appearance is slightly better, but it is obvious that “he had suffered severely from illness and want, and was still very weak.” I found it very telling that Jingle “took off his hat as Mr Pickwick saluted him, and seemed humbled and abashed at sight of Sam Weller.” Next, along comes Job Trotter who also takes off his hat to Pickwick. Sam, amazed and confused by the presence of these two men, and the great humility and respect they show Pickwick, can only say “Well, I am damned. Which he repeated at least a score of times.” Sam is flummoxed. Perhaps we should be too. However, in this section of the chapter, Dickens intends to provide a lesson for both Sam and the novel’s readers. Sam is a man of many words, but in this case his actions speak louder than words, and so, to emulate Pickwick’s forgiveness and generosity, he takes Job to the tap and “called for pot of porter.” Once that was enjoyed, Sam offers to get Job some “whittles” to which Job replies “[t]hanks to your worthy governor, sir.” We find out that Pickwick has been providing better accommodation, food, and clothes for Jingle and Job.

Jingle and Job leave and we then get a meditation from Dickens on how the people in the Fleet “all lounged, and loitered, and slunk about, with as little spirit or purpose as the beasts in a menagerie.” We then read of how corrupt the jail is with the sanction of Mr Roker and others. Dickens writes, “[t]he whole place seemed restless and troubled, and the people were crowding and flitting to and fro, like the shadows in an uneasy dream.” The Fleet experience overwhelms Pickwick, and as the end of the chapter comes, Mr Pickwick announces that “[h]enceforth I will be a prisoner in my own room.” And so it was. For three long months Pickwick remained shut up in his room, and nothing and no one, even Sam, “could induce him to alter one jot of his inflexible resolution.”

Thoughts

The arc of the last two chapters is quite remarkable. In the end of Chapter 44 the cobbler dies, having lived a lifeless existence. Chapter 45 begins with high humour, exuberant characters, and physical activity. Now, Chapter 45 ends with Pickwick reflecting the existence of the cobbler. Pickwick’s benevolence and forgiveness of others has not been transferred or fully internalized by himself. How did you react to the structure of these two chapters?

Our recent chapters have lead us from the joy and happiness and freshness of Dingley Dell to the fetid world of the Fleet prison. We seem to be moving into a world of reality, of pain, of true suffering. What other instances of a major shift in tone have you encountered?

This is quite the chapter. Who knew that so much character development, plot advancement, humour, and pathos could be packed into so few pages? We will stay within the walls of the Fleet, but that will not limit the scope of our reading. And so first, let us follow Sam after he makes up Mr Pickwick’s room.

The Fleet prison seems large and offers much for the prisoner to enjoy. We find Sam on a bench with a beer in his hand and an old newspaper from which to read the police reports beside him. He sends a platonic wink towards a young lady peeling potatoes. Sam is content. I can’t remember if we have been told before, but it is interesting to note that Sam can read.

Sam’s first visitor of the day is his father who is bursting with joy at the news that Sam’s step-mother and the red-nosed Stiggins have come for a visit. With a wink about Sam not mentioning who Sam’s creditor is, Sam’s father recounts how he brought Stiggins to the jail by giving him the most memorable, bouncy, and horrid coach ride possible. As Weller senior says, “he was a flyin’ out o’ the harmcheer all the way.” What a wonderful way to create the word armchair. The words “harm” and the word “cheer” give a perfect description with meaning. No doubt Weller senior would enjoy causing innocent “harm” to Stiggins. What “cheer” would Weller have enjoyed as Stiggins bounced about. In future I must look more carefully at how Dickens constructs his dialect. What follows is enormous fun. Stiggins attempts to save Sam from his apparent fallen state, but can only do so by finding his own spirit in a bottle. Mrs Weller joins in on the intervention, but does so only after an alcoholic intervention on herself. While this scene is being played out, Mr Weller senior is busy aping and pantomiming the proceedings. Mr Weller sums up the disastrous event by observing “that wot they drink, don’t seem no nourishment to ‘me; it all turns to warm water, and comes pourin’ out o’ their eyes. ‘Pend upon it, Sammy, it’s a consritootional infirmity.” Crocodile tears from too many beers perhaps? Stiggins insists that Sam should, at all costs, avoid intoxication. This conclusion comes, of course, at the height of Stiggins own drunkenness.

Before Mr Weller senior leaves he tells his son that he has a plan to help Mr Pickwick escape. It has to do with stuffing Pickwick into a hollow piano forte and sending it to “Merriker.” The Americans, reasons Mr Weller, will welcome Pickwick’s money. Thus, if Pickwick stays in America until Mrs Bardell dies or Mr Dodson and Fog are hanged, Pickwick will be safe. There is something appealing to this bizarre plan. Weller senior does have a vivid imagination.

Thoughts

The first part of Sam’s day in the Fleet yard is entertaining. From settling in to read a newspaper, to winking at a young lady, to the visit from his father, step mother and Stiggins, Dickens keeps the tone light, humourous, and entertaining. Do you think Dickens overdid the broad humour, or did you find this part of the chapter an enjoyable experience?

Clearly, Dickens has no patience with reverend Stiggins. To what extent did you find Dickens’s characterization of Stiggins believable?

I found the second part of this chapter an abrupt change in tone, focus, and style. Dickens moves us from the broad humour of Sam’s encounters in the first part of the chapter to a much more somber reflection on how the vagrancies of life and the incarceration of an individual can ruin any person. I found the second part of this chapter much like that of Chapter 44 where the cobbler “so like death in life” does die. Dickens creates extremes in emotion and life by changing the mood of Chapter 45 very abruptly. Within a few sentences of Mr Weller leaving Sam, Mr Pickwick and Sam meet Mr Jingle. Through the previous kindness of Pickwick, Jingle’s appearance is slightly better, but it is obvious that “he had suffered severely from illness and want, and was still very weak.” I found it very telling that Jingle “took off his hat as Mr Pickwick saluted him, and seemed humbled and abashed at sight of Sam Weller.” Next, along comes Job Trotter who also takes off his hat to Pickwick. Sam, amazed and confused by the presence of these two men, and the great humility and respect they show Pickwick, can only say “Well, I am damned. Which he repeated at least a score of times.” Sam is flummoxed. Perhaps we should be too. However, in this section of the chapter, Dickens intends to provide a lesson for both Sam and the novel’s readers. Sam is a man of many words, but in this case his actions speak louder than words, and so, to emulate Pickwick’s forgiveness and generosity, he takes Job to the tap and “called for pot of porter.” Once that was enjoyed, Sam offers to get Job some “whittles” to which Job replies “[t]hanks to your worthy governor, sir.” We find out that Pickwick has been providing better accommodation, food, and clothes for Jingle and Job.

Jingle and Job leave and we then get a meditation from Dickens on how the people in the Fleet “all lounged, and loitered, and slunk about, with as little spirit or purpose as the beasts in a menagerie.” We then read of how corrupt the jail is with the sanction of Mr Roker and others. Dickens writes, “[t]he whole place seemed restless and troubled, and the people were crowding and flitting to and fro, like the shadows in an uneasy dream.” The Fleet experience overwhelms Pickwick, and as the end of the chapter comes, Mr Pickwick announces that “[h]enceforth I will be a prisoner in my own room.” And so it was. For three long months Pickwick remained shut up in his room, and nothing and no one, even Sam, “could induce him to alter one jot of his inflexible resolution.”

Thoughts

The arc of the last two chapters is quite remarkable. In the end of Chapter 44 the cobbler dies, having lived a lifeless existence. Chapter 45 begins with high humour, exuberant characters, and physical activity. Now, Chapter 45 ends with Pickwick reflecting the existence of the cobbler. Pickwick’s benevolence and forgiveness of others has not been transferred or fully internalized by himself. How did you react to the structure of these two chapters?

Our recent chapters have lead us from the joy and happiness and freshness of Dingley Dell to the fetid world of the Fleet prison. We seem to be moving into a world of reality, of pain, of true suffering. What other instances of a major shift in tone have you encountered?

Chapter 46

There are chapters, or parts of chapters, that befuddle me when reading Dickens, and Chapter 46 is one of them. So rather than try and bumble and mumble my way through it, I openly confess to my fellow Curiosities my hesitation and doubts. While I think I am comfortable discussing the last part of this chapter, it does come after the first part, so here goes.

We find ourselves in a cabriolet with the driver and three passengers, two of whom are “vixenish-looking ladies” and the other “a gentleman of heavy and subdued demeanour.” The single woman is Mrs Cluppins, and the married couple are the Raddle’s. They all are on their way to Mrs Bardell’s house. The women think it is the house with the yellow door while the gentleman thinks it has a green door. Bickering ensues and they decide, by a vote, no less, to go to the house with the yellow door. Naturally it is not the right house, for Master Thomas Bardell appears at the window of a house with a red door. The cab driver is distressed because he was unable to arrive at the Bardell’s with dash and flair. Upon questioning, Tommy Bardell reveals that Mrs Bardell’s present lodger, a Mrs Rogers, will also be part of this planned outing. While this conversation was going on we read that the Raddle’s were involved in a dispute over the cab fare. Later, the women gang up on Mr Raddle who wisely retreats to the back yard.

Thoughts

It could be me (and probably is) but I found these first paragraphs were lacking in humour. I found the first paragraphs containing the coloured door confusion, the discussion with Tommy Bardell, the cab fare confusion, the retreat of Mr Raddle to the backyard, and the women’s discussion were little more than nonsense as opposed to humourous. How humourous did you find these opening paragraphs?

We have seen, over and over again in this novel, how Dickens writes many of his chapters in a binary fashion. Here we have a section where we have women dominating a man. As we know from this chapter’s end, Mrs Bardell is not in control of her situation or future. Did you find these early paragraphs successfully established the binary nature of this chapter's conclusion?

The Bardell picnic party are going to the Spaniards, at Hampstead. I am using the Penguin edition and there is a note that comments that the Spaniards, at Hampstead was “an eighteenth-century tavern and tea gardens where the Gordon Rioters were overtaken by the military in 1780, and which claims to have Dick Turpin’s original pistols.” Now, this choice of location I found interesting. Here is a slight digression... Barnaby Rudge, Dickens’s fifth novel and largely set during the time of the Gordon Riot’s, was, at one time, going to be Dickens’s first novel, but due to publisher difficulties was delayed and appeared in Master Humphrey's Clock.

Thoughts

Since I seem to be in a rather speculative mood, here is another thought I had. For fun, to what extent could we see Mr. Pickwick as a benevolent Dick Turpin figure? They both enjoy travelling the highways and bi-ways of England, they both find adventures and misadventures along the way, they both cut a rather dashing and romantic figure, they both spend time in jail and they both have become, in some ways, iconic figures of British legend and name recognition. Dick Turpin became a cult figure, a figure and focus of ballads and print just as Pickwick would become ingrained into the lore of English social history.What do you think?

In any case, the picnic group has tea and Mrs Bardell’s new boarder comments “How sweet the country is, to be sure! ... I almost wish I lived in it always.” This comment sets off a mini-earthquake of emotion. After much sound and fury, the sound of a hackney-coach is heard and Mr Jackson, from Dodson and Fogg, arrives on the scene. With Mr Jackson is a rather shabby man carrying an ash stick. Jackson announces that Mrs Bardell is wanted in the city on “pressing business.” Mrs Bardell thinks such a summons will impress her first floor lodger. Mr Jackson explicitly points out to the man with the stick who Mrs Bardell is. Strange action, don’t you think? Doing this, away they go back to the city.

They arrive at “a curious place: a large wall, with a gate in the middle, and a gaslight burning inside.” Mrs Bardell is told that she is at “one of our public offices.” A door “swung heavily” and they “descended a small flight of steps.” It turns out that Mrs Bardell has been taken to the Fleet “in execution of them costs.” Lawyers, it seems, have loyalty to their client’s money much more than to their clients. And there she encounters Mr Pickwick, taking the night air with Sam, and who, upon seeing Mrs Bardell, “took his hat off with mock reference, while his master turned indignantly on his heel.” And so the chapter ends with Mrs Bardell who “had fainted in real downright earnest.”

Now, this last part of the chapter was delightful. Bardell has become entrapped in her own web that has been spun by Dodson and Fogg. I can forget the unhumourous beginning of the chapter. Here we have a vivid, surprising, and satisfying chapter ending. The Fleet has welcomed another debtor. The potential for further plot development has been established.

Thoughts

Did you anticipate this event? To what extent do you think Dickens foreshadowed what might befall Mrs Bardell?

With the linking of the various characters and plot lines The Pickwick Papers has moved beyond simply being simply episodic or picaresque work and become a well-crafted and tightly plotted novel? What do you think has moved this novel from being episodic to novelistic?

Were you surprised that while Pickwick was quick to embrace and help Jingle and Job he obviously wants nothing to do with Mrs Bardell? How do you account for the differences in his reactions?

There are chapters, or parts of chapters, that befuddle me when reading Dickens, and Chapter 46 is one of them. So rather than try and bumble and mumble my way through it, I openly confess to my fellow Curiosities my hesitation and doubts. While I think I am comfortable discussing the last part of this chapter, it does come after the first part, so here goes.

We find ourselves in a cabriolet with the driver and three passengers, two of whom are “vixenish-looking ladies” and the other “a gentleman of heavy and subdued demeanour.” The single woman is Mrs Cluppins, and the married couple are the Raddle’s. They all are on their way to Mrs Bardell’s house. The women think it is the house with the yellow door while the gentleman thinks it has a green door. Bickering ensues and they decide, by a vote, no less, to go to the house with the yellow door. Naturally it is not the right house, for Master Thomas Bardell appears at the window of a house with a red door. The cab driver is distressed because he was unable to arrive at the Bardell’s with dash and flair. Upon questioning, Tommy Bardell reveals that Mrs Bardell’s present lodger, a Mrs Rogers, will also be part of this planned outing. While this conversation was going on we read that the Raddle’s were involved in a dispute over the cab fare. Later, the women gang up on Mr Raddle who wisely retreats to the back yard.

Thoughts

It could be me (and probably is) but I found these first paragraphs were lacking in humour. I found the first paragraphs containing the coloured door confusion, the discussion with Tommy Bardell, the cab fare confusion, the retreat of Mr Raddle to the backyard, and the women’s discussion were little more than nonsense as opposed to humourous. How humourous did you find these opening paragraphs?

We have seen, over and over again in this novel, how Dickens writes many of his chapters in a binary fashion. Here we have a section where we have women dominating a man. As we know from this chapter’s end, Mrs Bardell is not in control of her situation or future. Did you find these early paragraphs successfully established the binary nature of this chapter's conclusion?

The Bardell picnic party are going to the Spaniards, at Hampstead. I am using the Penguin edition and there is a note that comments that the Spaniards, at Hampstead was “an eighteenth-century tavern and tea gardens where the Gordon Rioters were overtaken by the military in 1780, and which claims to have Dick Turpin’s original pistols.” Now, this choice of location I found interesting. Here is a slight digression... Barnaby Rudge, Dickens’s fifth novel and largely set during the time of the Gordon Riot’s, was, at one time, going to be Dickens’s first novel, but due to publisher difficulties was delayed and appeared in Master Humphrey's Clock.

Thoughts

Since I seem to be in a rather speculative mood, here is another thought I had. For fun, to what extent could we see Mr. Pickwick as a benevolent Dick Turpin figure? They both enjoy travelling the highways and bi-ways of England, they both find adventures and misadventures along the way, they both cut a rather dashing and romantic figure, they both spend time in jail and they both have become, in some ways, iconic figures of British legend and name recognition. Dick Turpin became a cult figure, a figure and focus of ballads and print just as Pickwick would become ingrained into the lore of English social history.What do you think?

In any case, the picnic group has tea and Mrs Bardell’s new boarder comments “How sweet the country is, to be sure! ... I almost wish I lived in it always.” This comment sets off a mini-earthquake of emotion. After much sound and fury, the sound of a hackney-coach is heard and Mr Jackson, from Dodson and Fogg, arrives on the scene. With Mr Jackson is a rather shabby man carrying an ash stick. Jackson announces that Mrs Bardell is wanted in the city on “pressing business.” Mrs Bardell thinks such a summons will impress her first floor lodger. Mr Jackson explicitly points out to the man with the stick who Mrs Bardell is. Strange action, don’t you think? Doing this, away they go back to the city.

They arrive at “a curious place: a large wall, with a gate in the middle, and a gaslight burning inside.” Mrs Bardell is told that she is at “one of our public offices.” A door “swung heavily” and they “descended a small flight of steps.” It turns out that Mrs Bardell has been taken to the Fleet “in execution of them costs.” Lawyers, it seems, have loyalty to their client’s money much more than to their clients. And there she encounters Mr Pickwick, taking the night air with Sam, and who, upon seeing Mrs Bardell, “took his hat off with mock reference, while his master turned indignantly on his heel.” And so the chapter ends with Mrs Bardell who “had fainted in real downright earnest.”

Now, this last part of the chapter was delightful. Bardell has become entrapped in her own web that has been spun by Dodson and Fogg. I can forget the unhumourous beginning of the chapter. Here we have a vivid, surprising, and satisfying chapter ending. The Fleet has welcomed another debtor. The potential for further plot development has been established.

Thoughts

Did you anticipate this event? To what extent do you think Dickens foreshadowed what might befall Mrs Bardell?

With the linking of the various characters and plot lines The Pickwick Papers has moved beyond simply being simply episodic or picaresque work and become a well-crafted and tightly plotted novel? What do you think has moved this novel from being episodic to novelistic?

Were you surprised that while Pickwick was quick to embrace and help Jingle and Job he obviously wants nothing to do with Mrs Bardell? How do you account for the differences in his reactions?

Peter, I might have got it wrong but I don't think it was the cobbler who died, i.e. the old man who entertained Sam with the story of his life and his tobacco smoke, but the other Chancery prisoner, i.e. Mr. Pickwick's landlord - the man whom Mr. Pickwick rented his private room from.

The Cobbler's Tale - this sounds like one contribution to the Canterbury Tales - was probably meant by the narrator to provide an example of somebody who has got into debt prison through no fault of his own. It's quite obvious that people like Smangle and Mivins have run up debts because of their own fecklessness, and so we might not feel inclined to pity them at all - I certainly don't -, and that's why it was necessary for the narrator to introduce to us another kind of prisoner in order to show that the debtor's prison was something that could simply happen to you if you got entangled with the law. Just like it happened to Mr. Pickwick. This way, we may see the injustices of the system because in the cobbler's and the other Chancery prisoner's case, we are not able to rightfully say, Serves them right.

I also like the story of the man who shot himself on principle because I took it as Sam's way of gentling criticizing his master's obduracy to rather rot in prison (on principle) than to pay the money to Dodson and Fogg which he, Mr. Pickwick, feels is not due to them.

The novel indeed becomes more coherent in these chapters, and we can see Mr. Pickwick's decision to withdraw from his environment altogether - at a certain cost to his general healt - both as an act of self-cleansing and an act of personal crisis. Let's not forget that Mr. Pickwick, who now decides he wants nothing to do with anyone, anymore, was originally a very outgoing and open person, somebody who always had his notebook ready to jot down whatever experiences and information he could get about the world around him. Now, however, he becomes a disillusioned and broken recluse.

Like you, I did not really enjoy the beginning of Chapter 46, and I had a feeling that it was written merely to achieve the usual length of one instalment. The Raddles are not central to the plot, and the whole husband and wife thing had been done before, even in PP. By the way, I had the same impression of Dickens just writing for the sake of getting his instalment full when Mr. Pell was introduced. One can see that the novel is drawing to a close.

The Cobbler's Tale - this sounds like one contribution to the Canterbury Tales - was probably meant by the narrator to provide an example of somebody who has got into debt prison through no fault of his own. It's quite obvious that people like Smangle and Mivins have run up debts because of their own fecklessness, and so we might not feel inclined to pity them at all - I certainly don't -, and that's why it was necessary for the narrator to introduce to us another kind of prisoner in order to show that the debtor's prison was something that could simply happen to you if you got entangled with the law. Just like it happened to Mr. Pickwick. This way, we may see the injustices of the system because in the cobbler's and the other Chancery prisoner's case, we are not able to rightfully say, Serves them right.

I also like the story of the man who shot himself on principle because I took it as Sam's way of gentling criticizing his master's obduracy to rather rot in prison (on principle) than to pay the money to Dodson and Fogg which he, Mr. Pickwick, feels is not due to them.

The novel indeed becomes more coherent in these chapters, and we can see Mr. Pickwick's decision to withdraw from his environment altogether - at a certain cost to his general healt - both as an act of self-cleansing and an act of personal crisis. Let's not forget that Mr. Pickwick, who now decides he wants nothing to do with anyone, anymore, was originally a very outgoing and open person, somebody who always had his notebook ready to jot down whatever experiences and information he could get about the world around him. Now, however, he becomes a disillusioned and broken recluse.

Like you, I did not really enjoy the beginning of Chapter 46, and I had a feeling that it was written merely to achieve the usual length of one instalment. The Raddles are not central to the plot, and the whole husband and wife thing had been done before, even in PP. By the way, I had the same impression of Dickens just writing for the sake of getting his instalment full when Mr. Pell was introduced. One can see that the novel is drawing to a close.

Tristram wrote: "Peter, I might have got it wrong but I don't think it was the cobbler who died, i.e. the old man who entertained Sam with the story of his life and his tobacco smoke, but the other Chancery prisone..."

Tristram

Yes. You are correct. It is Pickwick’s landlord who dies. I have made the change in the commentary. Good catch.

Tristram

Yes. You are correct. It is Pickwick’s landlord who dies. I have made the change in the commentary. Good catch.

"Do you always smoke after you goes to bed, old cock?" inquired Mr. Weller of his land-lord, when they had both retired for the night.

Chapter 44

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Although Thomas Nast offered illustrations for neither chapter 43 nor chapter 44 in the Harper and Brothers version of the Household Edition for The Pickwick Papers, providing instead a woodcut relating to the comic Reverent Stiggins subplot in chapter 45, Phiz took this opportunity to create entirely new illustrations for these chapters. Neither illustration has a counterpart in the original serial illustrations, and both are among the seventeen entirely new illustrations that Phiz developed for the Household Edition, giving him the opportunity to balance the fortunes of Samuel Pickwick and those of Sam Weller, making the latter in essence the novel's co-protagonist. Neither this nor the previous illustration, "Sam, having been formally introduced . . . . as the offspring of Mr. Weller, of the Belle Savage, was treated with marked distinction", has a counterpart in the original serial illustrations, and both are among the seventeen entirely original illustrations that Phiz developed for the Household Edition, giving him the opportunity to focus on the character and fortunes of Sam Weller, making him in essence the novel's co-protagonist. In fact, in the fifty-seven illustrations in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, Pickwick appears in just twenty-two, Sam (despite the fact that he doesn't make an appearance in the initial chapters) in twenty-two — the pair together in eight of the woodcuts.

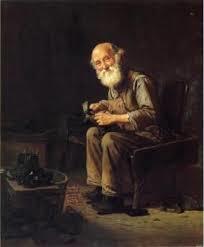

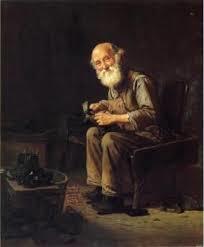

In chapter 44, although Nathaniel Winkle requests Sam's assistance in prosecuting his romantic pursuit of Arabella Allen, Sam is not free to leave the Fleet, where he settles in comfortably, as always making the best of a bad lot (in this case, being incarcerated for a debt he owes his father), as we see in the 1873 illustration and the following passage involving Sam's dialogue with his landlord, a cobbler who has fallen victim to Doctors' Commons and Chancery over legal actions brought against him when he became the executor of a relative's estate:

Finding all gentle remonstrance useless, Mr. Pickwick at length yielded a reluctant consent to his taking lodgings by the week, of a bald-headed cobbler, who rented a small slip room in one of the upper galleries. To this humble apartment Mr. Weller moved a mattress and bedding, which he hired of Mr. Roker; and, by the time he lay down upon it at night, was as much at home as if he had been bred in the prison, and his whole family had vegetated therein for three generations.

"Do you always smoke arter you goes to bed, old cock?" inquired Mr. Weller of his landlord, when they had both retired for the night.

"Yes, I does, young bantam," replied the cobbler.

"Will you allow me to in-quire wy you make up your bed under that 'ere deal table?" said Sam.

"Cause I was always used to a four-poster afore I came here, and I find the legs of the table answer just as well," replied the cobbler.

"You're a character, sir," said Sam.

"I haven't got anything of the kind belonging to me," rejoined the cobbler, shaking his head; "and if you want to meet with a good one, I'm afraid you'll find some difficulty in suiting yourself at this register office."

The above short dialogue took place as Mr. Weller lay extended on his mattress at one end of the room, and the cobbler on his, at the other; the apartment being illumined by the light of a rush-candle, and the cobbler's pipe, which was glowing below the table, like a red-hot coal. The conversation, brief as it was, predisposed Mr. Weller strongly in his landlord's favor; and, raising himself on his elbow, he took a more lengthened survey of his appearance than he had yet had either time or inclination to make.

He was a sallow man — all cobblers are; and had a strong bristly beard — all cobblers have. His face was a queer, good- tempered, crooked-featured piece of workmanship, ornamented with a couple of eyes that must have worn a very joyous expression at one time, for they sparkled yet. The man was sixty, by years, and Heaven knows how old by imprisonment, so that his having any look approaching to mirth or contentment, was singular enough. He was a little man, and, being half doubled up as he lay in bed, looked about as long as he ought to have been without his legs. He had a great red pipe in his mouth, and was smoking, and staring at the rush-light, in a state of enviable placidity.

"Have you been here long?' inquired Sam, breaking the silence which had lasted for some time.

"Twelve year," replied the cobbler, biting the end of his pipe as he spoke.

"'Contempt?" inquired Sam. The cobbler nodded.

'

"Well, then," said Sam, with some sternness, "wot do you persevere in bein' obstinit for, vastin' your precious life away, in this here magnified pound? Wy don't you give in, and tell the Chancellorship that you're wery sorry for makin' his court contemptible, and you won't do so no more?"

The cobbler put his pipe in the corner of his mouth, while he smiled, and then brought it back to its old place again; but said nothing.

"Wy don't you?" said Sam, urging his question strenuously.

"Ah,' said the cobbler, "you don't quite understand these matters. What do you suppose ruined me, now?"

"Wy,' said Sam, trimming the rush-light, 'I s'pose the beginnin' wos, that you got into debt, eh?"

"Never owed a farden," said the cobbler; "try again."

"Well, perhaps," said Sam, "you bought houses, wich is delicate English for goin' mad; or took to buildin', wich is a medical term for bein' incurable."

The cobbler shook his head and said, 'Try again.' 'You didn't go to law, I hope?' said Sam suspiciously. 'Never in my life,' replied the cobbler. 'The fact is, I was ruined by having money left me."

"Come, come," said Sam, 'that von't do. I wish some rich enemy 'ud try to vork my destruction in that 'ere vay. I'd let him."

"Oh, I dare say you don't believe it," said the cobbler, quietly smoking his pipe. "I wouldn't if I was you; but it's true for all that."

"How wos it?" inquired Sam, half induced to believe the fact already, by the look the cobbler gave him.

There follows what amounts to an integrated first-person narrative on the vagaries of the English legal system. The illustration conveys a sense of both characters, the sanguine old cobbler and the equally sanguine Sam Weller, both sleeping on the floor of a spacious furnished apartment. Although the rush light is positioned on the mantelpiece, the room seems much better lit than Dickens describes. Whereas the cobbler's pipe is "glowing below the table, like a red-hot coal" because the room is in near darkness, Phiz communicates the effect through its billowing smoke, somewhat altering the atmosphere of the ensuing dialogue. The old man's attitudes about the injustices of the property-inheritance system and his gradually revealed bitterness are not suggested, so that the illustration does not seem to be referring to anything of substance, whereas the cobbler's tale is Dickens's indictment of a system he knew so well as a legal clerk and then a reporter. Unfortunately, although this illustration conveys an accurate image of the physical particulars of the old cobbler, it presents a "sanitized" image of life in a debtors' prison, suggesting that Phiz (unlike Boz) was unfamiliar with conditions in such places in the 1830s, the misery, the dinginess, the lack of sanitation, and the all-consuming desperation rampant in these deplorable institutions.

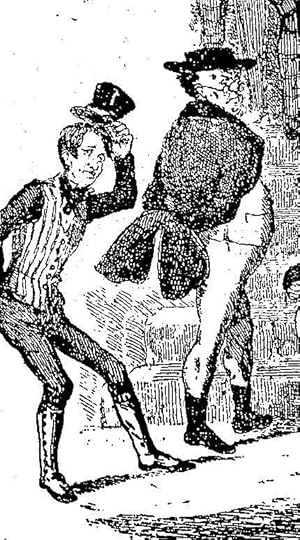

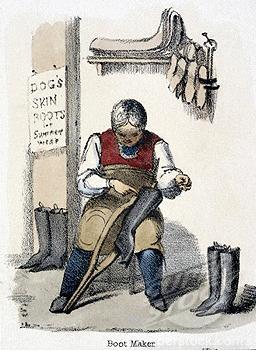

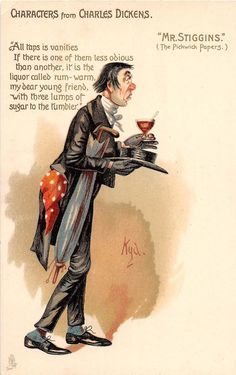

The Red-Nosed Man Discourseth

Chapter 45

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

Having satirized education in the plot gambit involving the seminary for young ladies and the law in "The Trial," Phiz and Dickens now assail the church in the person of a dissenting preacher named Stiggins, whom Tony Weller derisively has denominated as "the red-nosed man" — a reference to the outward and visible sign of his hypocrisy. Thew Reverend Stiggins as the chief of the Dorking branch of the Brick Lane Branch of the United Grand Junction Ebenezer Temperance Association is Mrs. Weller's spiritual counsellor. Even as the temperance preacher criticises taps (public houses) as "vanities," he asks Sam to order him hot rum and water. Apparently, Sam's step-mother ("mother-in-law") has brought the preacher to the Fleet Prison to exhort Sam to repent his dissolute ways that have led to his incarceration for debt — clearly she is unaware that Sam has contrived his status as debtor merely to watch over Mr. Pickwick. Sam, too, regards Stiggins as a "humbug," as he describes the preacher as "Saint Simon Without, and Saint Walker Within" (the reference being to the notorious spy Hookey Walker, the vehicle for expressions of incredulity such as that by the street boy whom Scrooge asks to bring the poulterer and prize turkey around to his residence on Christmas morning at the close of A Christmas Carol (1843).

Ever since his initial appearance in the story in chapter ten as the down-to-earth, practical-minded foil to the naive, good-hearted Pickwick in chapter ten (his arrival in the narrative commemorated in Phiz's "First Appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller"), the plucky, wise-cracking, street-smart Cockney had been a favourite with readers — and a continuing character in the picaresque novel, Sancho Panza to Pickwick's Don Quixote, so to speak. Now he assumes considerable prominence in an illustration. The plate, in fact, makes no reference to Sam's "master" whatsoever, for the characters are entirely below the mercantile Pickwick's social station: Mrs. Weller (left), sobbing; Stiggins (center) in full rhetorical flight; Sam's father, Tony, nodding off; and Sam, not "cross-legged" as indicated in the text, but rather straddling the chair in the Snuggery as if it were a horse.

Text illustrated

He furthermore conjured him to avoid, above all things, the vice of intoxication, which he likened unto the filthy habits of swine, and to those poisonous and baleful drugs which being chewed in the mouth, are said to filch away the memory. At this point of his discourse, the reverend and red-nosed gentleman became singularly incoherent, and staggering to and fro in the excitement of his eloquence, was fain to catch at the back of a chair to preserve his perpendicular.

Mr. Stiggins did not desire his hearers to be upon their guard against those false prophets and wretched mockers of religion, who, without sense to expound its first doctrines, or hearts to feel its first principles, are more dangerous members of society than the common criminal; imposing, as they necessarily do, upon the weakest and worst informed, casting scorn and contempt on what should be held most sacred, and bringing into partial disrepute large bodies of virtuous and well-conducted persons of many excellent sects and persuasions. But as he leaned over the back of the chair for a considerable time, and closing one eye, winked a good deal with the other, it is presumed that he thought all this, but kept it to himself.

During the delivery of the oration, Mrs. Weller sobbed and wept at the end of the paragraphs; while Sam, sitting cross-legged on a chair and resting his arms on the top rail, regarded the speaker with great suavity and blandness of demeanour; occasionally bestowing a look of recognition on the old gentleman, who was delighted at the beginning, and went to sleep about half-way.

‘Brayvo; wery pretty!’ said Sam, when the red-nosed man having finished, pulled his worn gloves on, thereby thrusting his fingers through the broken tops till the knuckles were disclosed to view. ‘Wery pretty.’

Detail:

The tearful Mrs. Weller

Mr. Stiggins, getting on his legs as well as he could, proceeded to deliver an edifying discourse for the benefit of the company

Chapter 45

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Weller delivered this scientific opinion with many confirmatory frowns and nods; which, Mrs. Weller remarking, and concluding that they bore some disparaging reference either to herself or to Mr. Stiggins, or to both, was on the point of becoming infinitely worse, when Mr. Stiggins, getting on his legs as well as he could, proceeded to deliver an edifying discourse for the benefit of the company, but more especially of Mr. Samuel, whom he adjured in moving terms to be upon his guard in that sink of iniquity into which he was cast; to abstain from all hypocrisy and pride of heart; and to take in all things exact pattern and copy by him (Stiggins), in which case he might calculate on arriving, sooner or later at the comfortable conclusion, that, like him, he was a most estimable and blameless character, and that all his acquaintances and friends were hopelessly abandoned and profligate wretches. Which consideration, he said, could not but afford him the liveliest satisfaction.

He furthermore conjured him to avoid, above all things, the vice of intoxication, which he likened unto the filthy habits of swine, and to those poisonous and baleful drugs which being chewed in the mouth, are said to filch away the memory. At this point of his discourse, the reverend and red-nosed gentleman became singularly incoherent, and staggering to and fro in the excitement of his eloquence, was fain to catch at the back of a chair to preserve his perpendicular.

Mr. Stiggins did not desire his hearers to be upon their guard against those false prophets and wretched mockers of religion, who, without sense to expound its first doctrines, or hearts to feel its first principles, are more dangerous members of society than the common criminal; imposing, as they necessarily do, upon the weakest and worst informed, casting scorn and contempt on what should be held most sacred, and bringing into partial disrepute large bodies of virtuous and well-conducted persons of many excellent sects and persuasions. But as he leaned over the back of the chair for a considerable time, and closing one eye, winked a good deal with the other, it is presumed that he thought all this, but kept it to himself.

Mr. Stiggins raised his hands and turned up his eyes

Chapter 45

Thomas Nast

Test Illustrated:

‘Mother-in-law,’ said Sam, politely saluting the lady, ‘wery much obliged to you for this here wisit.—Shepherd, how air you?’

‘Oh, Samuel!’ said Mrs. Weller. ‘This is dreadful.’

‘Not a bit on it, mum,’ replied Sam.—‘Is it, shepherd?’

Mr. Stiggins raised his hands, and turned up his eyes, until the whites—or rather the yellows—were alone visible; but made no reply in words.

‘Is this here gen’l’m’n troubled with any painful complaint?’ said Sam, looking to his mother-in-law for explanation.

‘The good man is grieved to see you here, Samuel,’ replied Mrs. Weller.

‘Oh, that’s it, is it?’ said Sam. ‘I was afeerd, from his manner, that he might ha’ forgotten to take pepper vith that ‘ere last cowcumber he eat. Set down, Sir, ve make no extra charge for settin’ down, as the king remarked wen he blowed up his ministers.’

‘Young man,’ said Mr. Stiggins ostentatiously, ‘I fear you are not softened by imprisonment.’

‘Beg your pardon, Sir,’ replied Sam; ‘wot wos you graciously pleased to hobserve?’

In the Same Place

Chapter 45

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Commentary:

The debtors' prison in which John Dickens was incarcerated when his son Charles was just twelve — The Marshalsea — gave the writer plenty of personal experience on which to draw for Pickwick's misadventures in the Fleet Rison in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.

Text Illustrated:

Here Mrs. Weller let fall some more tears, and Mr. Stiggins groaned.

"Hollo! Here’s this unfortunate gen'lm'n took ill agin," said Sam, looking round. "Vere do you feel it now, sir?"

"In the same place, young man,' rejoined Mr. Stiggins, 'in the same place."

"Vere may that be, Sir?" inquired Sam, with great outward simplicity.

"In the buzzim, young man," replied Mr. Stiggins, placing his umbrella on his waistcoat.

At this affecting reply, Mrs. Weller, being wholly unable to suppress her feelings, sobbed aloud, and stated her conviction that the red-nosed man was a saint; whereupon Mr. Weller, senior, ventured to suggest, in an undertone, that he must be the representative of the united parishes of St. Simon Without and St. Walker Within.

"I'm afeered, mum," said Sam, "that this here gen'l'm'n, with the twist in his countenance, feels rather thirsty, with the melancholy spectacle afore him. Is it the case, mum?"

The worthy lady looked at Mr. Stiggins for a reply; that gentleman, with many rollings of the eye, clenched his throat with his right hand, and mimicked the act of swallowing, to intimate that he was athirst. Chapter 45, "Descriptive of an affecting Interview between Mr. Samuel Weller and a Family Party. Mr. Pickwick makes a Tour of the diminutive World he inhabits, and resolves to mix with it, in Future, as little as possible,"

The shades of the prison house lift somewhat in the comic interlude between the "red-nosed man," the hypocritical nonconformist minister Mr. Stiggins (center), and his detractors, coachman Tony Weller (right) and his street-wise son, Sam (left). As Bentley, Slater, and Burgiss note,

'Without' and 'Within' refer to the City [of London's] boundaries are found as parts of names of streets and churches. Stiggins is Simon (St Simon the Zealot or perhaps Simon Pure) to all appearance, but Walker (cockney slang for 'humbug') in reality.

The difficulty for the illustrator lies in conveying this duplicity with subtlety, rather than rendering Stiggins an overblown drunkard. In the August 1837 installment, Phiz depicted the very same snuggery scene in Pickwick Papers, The Red-nosed Man Discourseth, and forty years later in the Household Edition revised it in the realistic manner of the sixties as Mr. Stiggins, getting on his legs as well as he could, proceeded to deliver an edifying discourse for the benefit of the company (1874). In the American Household Edition, political cartoonist Thomas Nast realizes much the same scene, but far less naturally, in Mr. Stiggins raised his hands, and turned up his eyes (1873), exaggerating for a gross comic effect.

Darley's ensemble study realizes each of the characters which the pictorial tradition established by the book's second illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, a tableau vivant manner, suggestive of a promotional theatrical photograph. As a realist, Darley perhaps takes the scene too seriously, for Stiggins is, as Ebenezer Scrooge would say, a "humbug": he is merely feigning illness, just as Sam is merely pretending to be solicitous for the dissenting minister's health. On the other hand, Darley's Mrs. Weller (left) is suitably concerned about the well-being of the Shepherd of the Brick Lane Flock — and her sardonic husband, every inch a coachman in his dress (even to the extent of carrying a long-handled whip indoors), suitably suspicious. Such satires of hypocritical clerics go all the way back to Chaucer's Monk and Friar in The Canterbury Tales, and were revivified by the advent of Methodism in the eighteenth century and teetotalism (1833). Perhaps the least satisfactory aspect of Darley's well organized composition is the snuggery itself, for it contains no tables, flagons, tankards, or even bottles. The orderly environment is hardly that of the chaotic misery and slovenliness of Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet, elements captured so well by Phiz in his 1837 caricature of the sermonizing hypocrite, whom Darley nonetheless effectively realizes in this illustration and the Preparations for Supper frontispiece of 1861, set in the Dorking public house run by the Wellers. That Darley features Stiggins as the subject of two of his four illustrations for Pickwick Papers invests the reprobate with an importance disproportionate to his relatively minor comic role in the novel, but the mid-nineteenth-century American illustrator must have felt the satirical figure of Stiggins in shabby black clerical suit more pertinent to contemporary society than the farcical companions of the bumbling but well-meaning Pickwick.

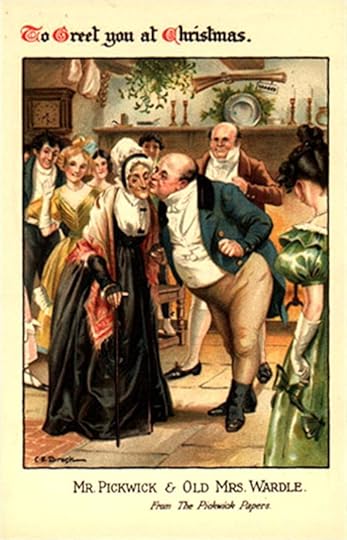

Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the Prison

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

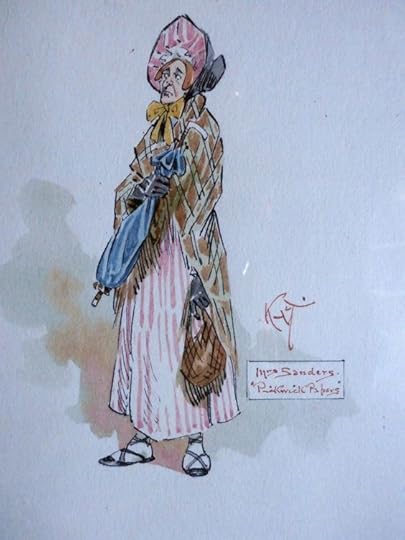

In the second of the August 1837 illustrations, the last of the debtors' prison sequence, Phiz realizes one of the key moments in the "breach of marriage" plot as Mr. Pickwick confronts his accuser, the devious Mrs. Bardell. The ingenious agent of Dodson and Fogg, Jackson, on the pretext of hastening the client to an emergency meeting with her attorneys, has just delivered Mrs. Bardell, Tommy Bardell, and Mrs. Cluppins to the central yard of the Fleet Prison. Since the scene is full of considerable emotion (ranging from Sam's facetiousness, Pickwick's hauteur, Mrs. Bardell's shocked disbelief, Tommy's roaring, and Mrs. Cluppins's terror) and contains a number of characters in varying poses, Phiz does not limit the picture with a vignette or frame; rather, he distributes the figures so that they seem to burst out of the margins as Sam (left) with mock politeness tips his hat, and Mrs. Sanders hastily exits in a baroque swirl of fabric (right), abandoning her friends to the very institution in which Mrs. Bardell had caused her mercenary agents to incarcerate Pickwick. Having used the unscrupulous Dodson and Fogg as her tools but having failed to pay her court costs, Mrs. Bardell is now the subject of poetic justice as her own attorneys (through their suave functionary, Jackson), Pickwick still proving obdurate, seize their own client "in execution of costs". To paraphrase Shakespeare's Hamlet, she has been hoisted on her own petard, and must become an inmate — together with her odious son Tommy (center, beside his shocked mother) — of the Fleet.

In this plate, the horizontal band formed by the main characters is juxtaposed both to the vertical of the gateway and to the dynamic thrust of the jailer, who appears to have just pushed the ladies and child down the steps. One reads from top to bottom left, and then to the right, just as one "sees" in the text the arrival at prison, the revelation to Mrs. Bardell that she is a prisoner, and then the encounter with Pickwick. The triangular arrangement, however, makes it possible to read the illustration in two directions, as though causally: from Mrs. Bardell up to the jailer and down to Pickwick, implying that her lawsuit has brought him to prison; or in reverse, beginning with Pickwick, implying that his stubborn adherence to principle has caused him unwittingly to make a victim out of his former landlady. Yet Pickwick and Mrs. Bardell also are part of the same compositional horizontal band, linked as victims of a vicious system. [Steig 36]

To emphasize their incarceration and loss of liberty, Phiz emphasizes the high iron bars (right), the stout stone archway and iron portcullis (upper center), and the turnkeys' utter disregard for the scene playing out beneath them. The overturned sewing basket (lower center) — a detail apparently of Phiz's invention — implies the utter frustration of Mrs. Bardell's designs upon Pickwick. Pickwick's posture (with his hands clutched under his coat-tails) echoes that of the scrutinizing turnkey (left) in "Mr. Pickwick Sits for His Portrait", implying that she, too, is about to undergo the humiliation of induction.

Text illustrated:

"What place is this?" inquired Mrs. Bardell, pausing.

"Only one of our public offices," replied Jackson, hurrying her through a door, and looking round to see that the other women were following. "Look sharp, Isaac!"

"Safe and sound," replied the man with the ash stick. The door swung heavily after them, and they descended a small flight of steps.

"Here we are at last. All right and tight, Mrs. Bardell!" said Jackson, looking exultingly round.

"What do you mean?" said Mrs. Bardell, with a palpitating heart.

"Just this," replied Jackson, drawing her a little on one side; "don't be frightened, Mrs. Bardell. There never was a more delicate man than Dodson, ma’am, or a more humane man than Fogg. It was their duty in the way of business, to take you in execution for them costs; but they were anxious to spare your feelings as much as they could. What a comfort it must be, to you, to think how it’s been done! This is the Fleet, ma’am. Wish you good–night, Mrs. Bardell. Good–night, Tommy!"

As Jackson hurried away in company with the man with the ash stick another man, with a key in his hand, who had been looking on, led the bewildered female to a second short flight of steps leading to a doorway. Mrs. Bardell screamed violently; Tommy roared; Mrs. Cluppins shrunk within herself; and Mrs. Sanders made off, without more ado. For there stood the injured Mr. Pickwick, taking his nightly allowance of air; and beside him leant Samuel Weller, who, seeing Mrs. Bardell, took his hat off with mock reverence, while his master turned indignantly on his heel.

"Don't bother the woman," said the turnkey to Weller; "she's just come in."

"A prisoner!" said Sam, quickly replacing his hat. "Who's the plaintives? What for? Speak up, old feller."

"Dodson and Fogg," replied the man; "execution on cognovit for costs."

Details;

The devious Mrs. Bardell

The indignant Mr. Pickwick

Mrs. Bardell screamed violently; Tommy roared; Mrs. Cluppins shrunk within herself, and Mrs. Sanders made off without more ado

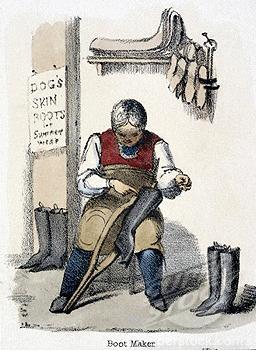

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Now, ladies,’ cried the man with the ash stick, looking into the coach, and shaking Mrs. Sanders to wake her, ‘Come!’ Rousing her friend, Mrs. Sanders alighted. Mrs. Bardell, leaning on Jackson’s arm, and leading Tommy by the hand, had already entered the porch. They followed.

The room they turned into was even more odd-looking than the porch. Such a number of men standing about! And they stared so!

‘What place is this?’ inquired Mrs. Bardell, pausing.

‘Only one of our public offices,’ replied Jackson, hurrying her through a door, and looking round to see that the other women were following. ‘Look sharp, Isaac!’

‘Safe and sound,’ replied the man with the ash stick. The door swung heavily after them, and they descended a small flight of steps.

‘Here we are at last. All right and tight, Mrs. Bardell!’ said Jackson, looking exultingly round.

‘What do you mean?’ said Mrs. Bardell, with a palpitating heart.

‘Just this,’ replied Jackson, drawing her a little on one side; ‘don’t be frightened, Mrs. Bardell. There never was a more delicate man than Dodson, ma’am, or a more humane man than Fogg. It was their duty in the way of business, to take you in execution for them costs; but they were anxious to spare your feelings as much as they could. What a comfort it must be, to you, to think how it’s been done! This is the Fleet, ma’am. Wish you good-night, Mrs. Bardell. Good-night, Tommy!’

As Jackson hurried away in company with the man with the ash stick another man, with a key in his hand, who had been looking on, led the bewildered female to a second short flight of steps leading to a doorway. Mrs. Bardell screamed violently; Tommy roared; Mrs. Cluppins shrunk within herself; and Mrs. Sanders made off, without more ado. For there stood the injured Mr. Pickwick, taking his nightly allowance of air; and beside him leant Samuel Weller, who, seeing Mrs. Bardell, took his hat off with mock reverence, while his master turned indignantly on his heel.

‘Don’t bother the woman,’ said the turnkey to Weller; ‘she’s just come in.’

‘A prisoner!’ said Sam, quickly replacing his hat. ‘Who’s the plaintives? What for? Speak up, old feller.’

‘Dodson and Fogg,’ replied the man; ‘execution on cognovit for costs.’

‘Here, Job, Job!’ shouted Sam, dashing into the passage. ‘Run to Mr. Perker’s, Job. I want him directly. I see some good in this. Here’s a game. Hooray! vere’s the gov’nor?’

But there was no reply to these inquiries, for Job had started furiously off, the instant he received his commission, and Mrs. Bardell had fainted in real downright earnest.

Mrs. Sanders

Kyd

Mrs. Sanders seems to be an unusual subject for an illustrations, but it is Kyd after all.

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Stiggins

Chapter 45

1910

Harry Furniss"

Kim

Thank you for the illustrations. I really like the Stiggins as portrayed by Harry Furniss. He has really captured the oily nature of Stiggins and the facial features and clothes are perfect. I love the steaming cup of liquid beside him. A gentle reminder of a satanic connection?

Mr. Stiggins

Chapter 45

1910

Harry Furniss"

Kim

Thank you for the illustrations. I really like the Stiggins as portrayed by Harry Furniss. He has really captured the oily nature of Stiggins and the facial features and clothes are perfect. I love the steaming cup of liquid beside him. A gentle reminder of a satanic connection?

Kim,

Thanks for providing all those different illustrations of the venerable Mr. Stiggins! He is, indeed, a most repulsive customer and aptly foreshadows the Pecksniffs and Chadbands to come. For all his criticism of clergymen, however, Dickens took care not to direct it against the Anglican Church proper but to restrict it to dissenters. Probably for two reasons: 1) He was not much in favour of what he deemed exaggerated piety, which deprives people of many actually harmless enjoyments in life. 2) He might not easily have got away with criticizing the Anglican Church in that a lot of his readers might have felt offended.

In Chapter 45, we also have a passage which makes Dickens's feelings about religious extremists very clear:

I rather like Dickens for reminding his readers of the essentially humane and kind nature of Christian doctrine instead of simply mocking religion as such. But that's just on a personal note.

Thanks for providing all those different illustrations of the venerable Mr. Stiggins! He is, indeed, a most repulsive customer and aptly foreshadows the Pecksniffs and Chadbands to come. For all his criticism of clergymen, however, Dickens took care not to direct it against the Anglican Church proper but to restrict it to dissenters. Probably for two reasons: 1) He was not much in favour of what he deemed exaggerated piety, which deprives people of many actually harmless enjoyments in life. 2) He might not easily have got away with criticizing the Anglican Church in that a lot of his readers might have felt offended.

In Chapter 45, we also have a passage which makes Dickens's feelings about religious extremists very clear:

"Mr. Stiggins did not desire his hearers to be upon their guard against those false prophets and wretched mockers of religion, who, without sense to expound its first doctrines, or hearts to feel its first principles, are more dangerous members of society than the common criminal; imposing, as they necessarily do, upon the weakest and worst informed, casting scorn and contempt on what should be held most sacred, and bringing into partial disrepute large bodies of virtuous and well–conducted persons of many excellent sects and persuasions. But as he leaned over the back of the chair for a considerable time, and closing one eye, winked a good deal with the other, it is presumed that he thought all this, but kept it to himself." (my underlinings)

I rather like Dickens for reminding his readers of the essentially humane and kind nature of Christian doctrine instead of simply mocking religion as such. But that's just on a personal note.

By the looks of Mr. Pickwick in the illustration in post 14 one might think that bad times are in store for poor Mrs. Bardell. Our otherwise so genial and benevolent hero looks as though he wanted to shake the dust of his coat-tails, and while he was ready to forgive Mr. Jingle, I do not find any signs of leniency towards Mrs. Bardell in his posture here. Has prison changed Mr. Pickwick for the worse?

Kim wrote: "Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the Prison

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

In the second of the August 1837 illustrations, the last of the debtors' prison sequence, Phiz realizes one..."

I’m not sure the word “wonderful” should ever refer to a scene where one is entering a jail, but this illustration is, well, wonderful. Sam’s tip of the hat, the shocked face of Mrs Bardell, the massive structure of the jail that contrasts so effectively with the recently disrupted Bardell picnic, and the shocked Tommy are captured at once. To me, I found Sam to be the best of all. There he is with his striped vest, so natty, and tipping his hat.

A last word for Tommy. He represents the callousness of the debtor’s system of justice. Regardless of his mother’s flaws, he is a child. Regardless of how he has turned out so far in life, his future in the Fleet will scar him forever. Although neither Phiz or any reader would have caught the total significance of Tommy entering the jail, Dickens himself would. I wonder to what extent Dickens paused at seeing this illustration and thought about his own past and his introduction to the Marshalsea, and how that would scar him for life?

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

In the second of the August 1837 illustrations, the last of the debtors' prison sequence, Phiz realizes one..."

I’m not sure the word “wonderful” should ever refer to a scene where one is entering a jail, but this illustration is, well, wonderful. Sam’s tip of the hat, the shocked face of Mrs Bardell, the massive structure of the jail that contrasts so effectively with the recently disrupted Bardell picnic, and the shocked Tommy are captured at once. To me, I found Sam to be the best of all. There he is with his striped vest, so natty, and tipping his hat.

A last word for Tommy. He represents the callousness of the debtor’s system of justice. Regardless of his mother’s flaws, he is a child. Regardless of how he has turned out so far in life, his future in the Fleet will scar him forever. Although neither Phiz or any reader would have caught the total significance of Tommy entering the jail, Dickens himself would. I wonder to what extent Dickens paused at seeing this illustration and thought about his own past and his introduction to the Marshalsea, and how that would scar him for life?

Tristram wrote: "By the looks of Mr. Pickwick in the illustration in post 14 one might think that bad times are in store for poor Mrs. Bardell. Our otherwise so genial and benevolent hero looks as though he wanted ..."

Tristram

“Has prison changed Mr. Pickwick for the worse?” Excellent question. We may or may not ever get a direct answer to your question as we complete our reading, but Pickwick’s time in the Fleet has certainly exposed him directly to a world that no story, tale or anecdote heard at an Inn would ever accomplish.

Tristram

“Has prison changed Mr. Pickwick for the worse?” Excellent question. We may or may not ever get a direct answer to your question as we complete our reading, but Pickwick’s time in the Fleet has certainly exposed him directly to a world that no story, tale or anecdote heard at an Inn would ever accomplish.

I was also confused about who died at the end of Chapter 44. I read the paragraph three times and changed my mind back and forth over and over. I finally decided I wasn't sure who died, but if it wasn't the cobbler, that maybe it was the cobbler who was sitting bedside-- ("a short old man in a cobbler's apron") -- reading the Bible aloud. Because then it says: "It was the fortunate legatee." as in, someone who received an inheritance. Like, the one who was reading, not the one who was dying.

I was also confused about who died at the end of Chapter 44. I read the paragraph three times and changed my mind back and forth over and over. I finally decided I wasn't sure who died, but if it wasn't the cobbler, that maybe it was the cobbler who was sitting bedside-- ("a short old man in a cobbler's apron") -- reading the Bible aloud. Because then it says: "It was the fortunate legatee." as in, someone who received an inheritance. Like, the one who was reading, not the one who was dying.Sometimes I hate when Dickens tries to be smooth, and I can't understand him!

Tristram wrote: "The novel indeed becomes more coherent in these chapters, and we can see Mr. Pickwick's decision to withdraw from his environment altogether - at a certain cost to his general healt - both as an act of self-cleansing and an act of personal crisis. Let's not forget that Mr. Pickwick, who now decides he wants nothing to do with anyone, anymore, was originally a very outgoing and open person, somebody who always had his notebook ready to jot down whatever experiences and information he could get about the world around him. Now, however, he becomes a disillusioned and broken recluse."

Tristram wrote: "The novel indeed becomes more coherent in these chapters, and we can see Mr. Pickwick's decision to withdraw from his environment altogether - at a certain cost to his general healt - both as an act of self-cleansing and an act of personal crisis. Let's not forget that Mr. Pickwick, who now decides he wants nothing to do with anyone, anymore, was originally a very outgoing and open person, somebody who always had his notebook ready to jot down whatever experiences and information he could get about the world around him. Now, however, he becomes a disillusioned and broken recluse."I love this observation!

He was a sallow man — all cobblers are; and had a strong bristly beard — all cobblers have,

Do they really? I went and looked and of course Kyd came through.

Cobbler of the Fleet

Here are a few others:

A prisoner in the Fleet, who rented a small slip-room in one of the upper galleries bald-headed. He was a sallow man all cobblers are and had a strong bristly beard - all cobblers have. His face was a queer, good-tempered piece of workmanship.

Do they really? I went and looked and of course Kyd came through.

Cobbler of the Fleet

Here are a few others:

A prisoner in the Fleet, who rented a small slip-room in one of the upper galleries bald-headed. He was a sallow man all cobblers are and had a strong bristly beard - all cobblers have. His face was a queer, good-tempered piece of workmanship.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the looks of Mr. Pickwick in the illustration in post 14 one might think that bad times are in store for poor Mrs. Bardell. Our otherwise so genial and benevolent hero looks as ..."

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the looks of Mr. Pickwick in the illustration in post 14 one might think that bad times are in store for poor Mrs. Bardell. Our otherwise so genial and benevolent hero looks as ..."Time in the Fleet seems to have brought out Mr. P's benevolence, at any rate. It was kind of back-burnered while he was out and about with his club--we'd get moments of his kindness, but also his pettiness. There are so many people for him to be kind to in prison that I end up with a different perception of his character than I had before. But it's interesting that this kindness is only on display because of his equally powerful stubbornness.

I don't know what opportunity Sam sees at the end of this installment, with the arrival of Mrs. Bardell, but I definitely have a guess!

~ Cheryl ~ wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The novel indeed becomes more coherent in these chapters, and we can see Mr. Pickwick's decision to withdraw from his environment altogether - at a certain cost to his general heal..."

Thank you. I just hope my observation will prove wrong because I don't want to lose the old Mr. Pickwick.

Thank you. I just hope my observation will prove wrong because I don't want to lose the old Mr. Pickwick.

Kim wrote: "He was a sallow man — all cobblers are; and had a strong bristly beard — all cobblers have,

Do they really? I went and looked and of course Kyd came through.

Cobbler of the Fleet

Here are a f..."

Another example of Kyd's craft ... Thank you, Kim!

Do they really? I went and looked and of course Kyd came through.

Cobbler of the Fleet

Here are a f..."

Another example of Kyd's craft ... Thank you, Kim!

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the Prison

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

In the second of the August 1837 illustrations, the last of the debtors' prison sequence, Phiz ..."

You are absolutely right about Tommy, Peter. But, strangely, all in all, Tommy remains a rather sketchy character, whereas later, Dickens used a lot of his craft to make us identify with children characters. In this, Pickwick is unusual.

Chapter 46

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

In the second of the August 1837 illustrations, the last of the debtors' prison sequence, Phiz ..."

You are absolutely right about Tommy, Peter. But, strangely, all in all, Tommy remains a rather sketchy character, whereas later, Dickens used a lot of his craft to make us identify with children characters. In this, Pickwick is unusual.

Peter wrote: "How humourous did you find these opening paragraphs?..."

Peter wrote: "How humourous did you find these opening paragraphs?..."I tend to agree that these passages were primarily padding, but I enjoyed them, nonetheless. It's no secret here that I'm drawn to Dickens for his humor more than his pathos, and I admit to busting out in a guffaw when it was discovered that Bardell house had a red door.

Like Tristram, I appreciate the distinction CD makes between the Christian and the doctrine. I wish culture commentators today could learn where that line is.

Would write more, but my husband is, quite literally, standing in the doorway, tapping his foot while waiting for us to leave for our daughter's. I wonder if Dickens has that scene in one of his novels somewhere...

Hello, fellow Curiosities

What’s this? Sam arrested for debt. He too will be a prisoner. While we don’t know who Sam’s demanding creditor is, (but can we guess?) we do have the pleasure of another Wellerism about a “wirtuous clergyman” who remarked to an old man with dropsy that “upon the whole he thought he’d rayther leave his property to his vife than build a chapel vith it.” Let’s just go along with Sam’s tale. I’m rather nervous about eating crumpets now. On the other hand, the crumpet tale, in its circuitous nature, did show how a person’s convictions can be very strong. Suffice to say, Sam will stay with Mr. Pickwick in the Fleet.

Sam shares his cell with a cobbler who has been in the Fleet for 12 years. The cobbler sleeps under a table since it reminds him of his old four post bed. In an interesting change of style what follows for the next two pages is the story of the cobbler. Unlike our previous stories, however, in this chapter Dickens weaves the tale of the cobbler into a question and answer format between the cobbler and Sam. It is a tale of an inheritance, and how the money ruined a family. The cobbler tells Sam that the court case “went into Chancery, where we are still, and where I shall always be.” The cobbler relates that he is in debt for ten thousand pounds. By the end of his story, Sam has fallen asleep, and so the cobbler puts his pipe down and falls asleep as well. Clearly, what begins in the court of Chancery remains in Chancery for a long, long time. Dickens will return to the black hole of the Chancery courts in Bleak House.

Thoughts

The cobbler’s tale is brief, and is presented to the reader in a slightly different format than our earlier tales. To what extent did you find its introductory format an effective style to introduce the tale?

Did you see any motifs in the tale that could connect it to the entire novel to date?

Mr Smangle tells Pickwick that three gentlemen are looking for him, and goes on to sing the praises of his own friend Mr Mivins and his pecuniary woes. It makes sense that a debtor’s prison would contain stories of debt, but I think Dickens is overdoing it a bit. Smangle touches Pickwick for money, promises to pay him back, and leaves. Mr Tupman, along with Winkle and Snodgrass, arrive for a visit with Mr Pickwick. Pickwick notices that Mr Winkle is unsettled and Winkle tells Pickwick that he must leave town for a short time and wants to take Sam with him. Well, here’s a mystery. It seems that Sam is aware of the mystery but neither Pickwick or the reader is let in on the meaning.

Next, Mr Roker comes to Pickwick with the news that his “landlord” is very ill. Pickwick, the kind and thoughtful man he is, asks to be taken to the infirmary where is found “the shadow of a man: wan, pale, and ghastly.” The dying man asks to have the window opened. What follows is a moving paragraph that evokes the sounds and smells of London, the sounds of people and objects of the world outside the prison. The sick man comments that “there is no air [in the prison] The places pollutes it.” The dying man laments that in bygone days “it was fresh round about, when I walked there, years ago; but it grows hot and heavy in passing these walls. I cannot breathe it. ... twenty years in this hideous grave.” Dickens, who so often is a master of many words, shows his command of succinct language as well when he has the turnkey comment that Pockwick’s landlord “got his discharge, by G—! He had. But he had grown so like death in life, that they knew not when he died.”

Thoughts

This was a curious chapter. We learn that Sam is now in jail with Mr Pickwick, we read a short tale that commences with a series of questions and answers, there is a truncated visit to the Fleet by Tupman, Snodgrass and Winkle, that Winkle plans to leave town and wants Sam to accompany him, and we witness the death of a long-suffering man who has been incarcerated for twenty years in the Fleet. What could be the reasons for so many seemingly unconnected bits in this chapter? Can you suggest how any of these events either explain any event that occurred in the past or anticipates what may happen in the future?

In terms of Dickens’s own life, his family spent months in the Marshalsea prison for debt. To what extent do you think that experience could have influenced any of the events in this chapter?

When reading this chapter it was impossible not to think of Dickens’s Little Dorrit. While we have discussed the possible connections before, would anyone like to make further comments on any possible links between the two novels? For our fellow Curiosities who have not read Little Dorrit yet, you are in for a treat. Stay tuned!