The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 41-43

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 42 takes us – and Mr. Pickwick – on a journey even deeper into the mysteries and atrocities of Fleet Prison. Here is what happens: Mr. Pickwick wakes up next morning to find himself in the presence of his faithful valet Sam, who is already waiting on him and, what is more, taking care lest his master should be taken in by his two new acquaintances. It is especially Mr. Smangle, who is stunned when he realizes that Sam is Mr. Pickwick’s manservant, and he immediately comes to the conclusion that Mr. Pickwick is, as someone who has a manservant – in prison!!! –, a man whose acquaintance is worth cultivating. Therefore, Mr. Smangle shows an avid desire to take care of Mr. Pickwick’s wardrobe, doubtless with a view of turning it into drink, but Sam wisely thwarts all his attempts.

Later in the morning, Mr. Roker tells Mr. Pickwick that he is going to be “chummed” with three other prisoners, and Mr. Pickwick guilelessly goes to find out where his new abode is. Alas! he not only finds his future room-mates very seedy characters but also the place in a shambles:

The three men are anything but happy at finding that another inmate has been singled out to share the cell with them, and they even resort to offering Mr. Pickwick money if he betook himself somewhere else. Now, our artless friend is given the following lecture:

It is quite interesting that the narrator points out that inside the prison the same laws of social life apply as outside, viz. that money rules the world, and that it helps set up a social hierarchy. In a way, life in Fleet Prison is a microcosm mirroring the world outside – a thought that does not really lead to an optimistic judgment of life itself. Do you think this was intended by the narrator?

Thus enlightened, Mr. Pickwick sees Mr. Roker again, who is not really surprised to find Mr. Pickwick come back to him. They soon find a (nameless) Chancery prisoner who is willing to let his own room to Mr. Pickwick, who rents the furniture from Mr. Roker. Apparently, the wardens have a lot of ways of earning extra-money and of exploiting the prisoners’ predicament. The Chancery prisoner brings a more tragic note into the story as the following quotation shows:

Mr. Pickwick is so moved by the strange man’s misery that he offers him the use of his room whenever he wants solitude or receives visitors. This is not the only sign of humanitarian feeling in Mr. Pickwick, for a little later he goes to a part of the prison where the poorest of the poor are locked up, and there he finds his old nemesis Mr. Jingle, as well as Job Trotter, both reduced to misery and shame. Mr. Jingle tries, for a few minutes, to show his old bravado, but he cannot hide any longer that, in fact, he is a broken man. Mr. Pickwick, seeing this, hesitates not a second but is ready to help his former enemies out with a little bit of money, while four large tears well up his eyes.

What do you think of Mr. Pickwick’s readiness to forgive Mr. Jingle? Is there any real development in our hero, or do you think this new turn of events unrealistic? How do you think the narrator treats this change in Mr. Pickwick?

This part of the chapter is played out on a more serious note even with an intrusive comment dismissing the idea of fiction:

After his encounter with Jingle and Trotter, Mr. Pickwick is moved to another magnanimous resolution when he tells Sam that Fleet Prison is surely not a place for a young man like him, due to its corrupting influences, and that he will pay his wages but insist on his no longer attending him in prison. He is even sure that one of his friends will employ Sam out of respect for him, Mr. Pickwick. As you can imagine, Sam is anything but pleased by Mr. Pickwick’s decision, and for the first time refuses to obey.

What possible foreshadowings do you see in some of the prisoners, e.g. in an old prisoner who is sitting in the poor part of the prison, with a granddaughter trying to comfort him?

Favourite quotations:

Later in the morning, Mr. Roker tells Mr. Pickwick that he is going to be “chummed” with three other prisoners, and Mr. Pickwick guilelessly goes to find out where his new abode is. Alas! he not only finds his future room-mates very seedy characters but also the place in a shambles:

”There was no vestige of either carpet, curtain, or blind. There was not even a closet in it. Unquestionably there were but few things to put away, if there had been one; but, however few in number, or small in individual amount, still, remnants of loaves and pieces of cheese, and damp towels, and scrags of meat, and articles of wearing apparel, and mutilated crockery, and bellows without nozzles, and toasting–forks without prongs, do present somewhat of an uncomfortable appearance when they are scattered about the floor of a small apartment, which is the common sitting and sleeping room of three idle men.”

The three men are anything but happy at finding that another inmate has been singled out to share the cell with them, and they even resort to offering Mr. Pickwick money if he betook himself somewhere else. Now, our artless friend is given the following lecture:

”After this introductory preface, the three chums informed Mr. Pickwick, in a breath, that money was, in the Fleet, just what money was out of it; that it would instantly procure him almost anything he desired; and that, supposing he had it, and had no objection to spend it, if he only signified his wish to have a room to himself, he might take possession of one, furnished and fitted to boot, in half an hour’s time.”

It is quite interesting that the narrator points out that inside the prison the same laws of social life apply as outside, viz. that money rules the world, and that it helps set up a social hierarchy. In a way, life in Fleet Prison is a microcosm mirroring the world outside – a thought that does not really lead to an optimistic judgment of life itself. Do you think this was intended by the narrator?

Thus enlightened, Mr. Pickwick sees Mr. Roker again, who is not really surprised to find Mr. Pickwick come back to him. They soon find a (nameless) Chancery prisoner who is willing to let his own room to Mr. Pickwick, who rents the furniture from Mr. Roker. Apparently, the wardens have a lot of ways of earning extra-money and of exploiting the prisoners’ predicament. The Chancery prisoner brings a more tragic note into the story as the following quotation shows:

”The Chancery prisoner had been there long enough to have lost his friends, fortune, home, and happiness, and to have acquired the right of having a room to himself. As he laboured, however, under the inconvenience of often wanting a morsel of bread, he eagerly listened to Mr. Pickwick’s proposal to rent the apartment, and readily covenanted and agreed to yield him up the sole and undisturbed possession thereof, in consideration of the weekly payment of twenty shillings; from which fund he furthermore contracted to pay out any person or persons that might be chummed upon it.”

Mr. Pickwick is so moved by the strange man’s misery that he offers him the use of his room whenever he wants solitude or receives visitors. This is not the only sign of humanitarian feeling in Mr. Pickwick, for a little later he goes to a part of the prison where the poorest of the poor are locked up, and there he finds his old nemesis Mr. Jingle, as well as Job Trotter, both reduced to misery and shame. Mr. Jingle tries, for a few minutes, to show his old bravado, but he cannot hide any longer that, in fact, he is a broken man. Mr. Pickwick, seeing this, hesitates not a second but is ready to help his former enemies out with a little bit of money, while four large tears well up his eyes.

What do you think of Mr. Pickwick’s readiness to forgive Mr. Jingle? Is there any real development in our hero, or do you think this new turn of events unrealistic? How do you think the narrator treats this change in Mr. Pickwick?

This part of the chapter is played out on a more serious note even with an intrusive comment dismissing the idea of fiction:

”We no longer suffer them [i.e. the poorest prisoners, T.S.] to appeal at the prison gates to the charity and compassion of the passers by; but we still leave unblotted the leaves of our statute book, for the reverence and admiration of succeeding ages, the just and wholesome law which declares that the sturdy felon shall be fed and clothed, and that the penniless debtor shall be left to die of starvation and nakedness. This is no fiction. Not a week passes over our head, but, in every one of our prisons for debt, some of these men must inevitably expire in the slow agonies of want, if they were not relieved by their fellow–prisoners.”

After his encounter with Jingle and Trotter, Mr. Pickwick is moved to another magnanimous resolution when he tells Sam that Fleet Prison is surely not a place for a young man like him, due to its corrupting influences, and that he will pay his wages but insist on his no longer attending him in prison. He is even sure that one of his friends will employ Sam out of respect for him, Mr. Pickwick. As you can imagine, Sam is anything but pleased by Mr. Pickwick’s decision, and for the first time refuses to obey.

What possible foreshadowings do you see in some of the prisoners, e.g. in an old prisoner who is sitting in the poor part of the prison, with a granddaughter trying to comfort him?

Favourite quotations:

”‘Why,’ said Mr. Roker, ‘it’s as plain as Salisbury. […]’”

”’ ‘Rides rather rusty,’ said Mr. Roker, with a smile. ‘Ah! they’re like the elephants. They feel it now and then, and it makes ’em wild!’”

Chapter 43 tells us what Sam is doing in order to circumvent Mr. Pickwick’s arrangement and still be able to attend to his old employer. His plan is as easy as brilliant, although involving additional costs: He borrows 25 £ from his father – who is let in on his plan, of course – and then refuses to pay back the loan. Mr. Weller senior then avails himself of the services of a Mr. Solomon Pell in order to have his own son confined to Fleet Prison, a procedure that surprisingly does not take 24 hours.

Apart from this turn of events, the chapter also includes some sketch material introducing Mr. Solomon Pell, a rather shady attorney at the Insolvent Debtor’s Court. According to the annotations in my Penguin edition, the Insolvent Debtor’s Court offered debtors the chance to, under certain conditions, get release from prison, but it was abolished in 1861. Our narrator gives us an example of how this works in the case of a colleague of Mr. Weller senior’s. If I understood it all correctly, the debtor, who is a coachman, has first of all got rid of his horses and coach by some legal trick so that, formally, he is bankrupt. The particulars of how he is spared prison, however, are not gone into, but we can be sure that Mr. Solomon Pell has not done this for the first time as he is really sure of his success. The whole episode may not directly (not even indirectly, now that I think of it) contribute to the plot but it surely serves to underline Dickens’s criticism of the legal system by pointing out another injustice. Mr. Pell is described like this:

The description of the surroundings – his place of doing business – makes it clear enough that notwithstanding his professional success, he is placed on one of the lower rungs of the legal ladder, but still Mr. Pell, either to impress his clients or to caress his own soul, entertains the fiction of his intimate acquaintance with the Lord Chancellor, who – in his version of a private conversation – says interesting things like this,

At the end of the chapter, the narrator takes up the actual plot by describing Mr. Weller and Mr. Pickwick’s first encounter in the prison after the conversation in which the master informed the servant about his decision. Characteristically, the narrator ends this instalment with another cliff-hanger in that we do not get Mr. Pickwick’s definite reaction to Mr. Weller’s announcement that he, too, is now a Fleet prisoner:

Apart from this turn of events, the chapter also includes some sketch material introducing Mr. Solomon Pell, a rather shady attorney at the Insolvent Debtor’s Court. According to the annotations in my Penguin edition, the Insolvent Debtor’s Court offered debtors the chance to, under certain conditions, get release from prison, but it was abolished in 1861. Our narrator gives us an example of how this works in the case of a colleague of Mr. Weller senior’s. If I understood it all correctly, the debtor, who is a coachman, has first of all got rid of his horses and coach by some legal trick so that, formally, he is bankrupt. The particulars of how he is spared prison, however, are not gone into, but we can be sure that Mr. Solomon Pell has not done this for the first time as he is really sure of his success. The whole episode may not directly (not even indirectly, now that I think of it) contribute to the plot but it surely serves to underline Dickens’s criticism of the legal system by pointing out another injustice. Mr. Pell is described like this:

”Mr. Solomon Pell, one of this learned body, was a fat, flabby, pale man, in a surtout which looked green one minute, and brown the next, with a velvet collar of the same chameleon tints. His forehead was narrow, his face wide, his head large, and his nose all on one side, as if Nature, indignant with the propensities she observed in him in his birth, had given it an angry tweak which it had never recovered. Being short–necked and asthmatic, however, he respired principally through this feature; so, perhaps, what it wanted in ornament, it made up in usefulness.”

The description of the surroundings – his place of doing business – makes it clear enough that notwithstanding his professional success, he is placed on one of the lower rungs of the legal ladder, but still Mr. Pell, either to impress his clients or to caress his own soul, entertains the fiction of his intimate acquaintance with the Lord Chancellor, who – in his version of a private conversation – says interesting things like this,

”’[…]“Pell,” he said, “no false delicacy, Pell. You’re a man of talent; you can get anybody through the Insolvent Court, Pell; and your country should be proud of you.”[…]’”

At the end of the chapter, the narrator takes up the actual plot by describing Mr. Weller and Mr. Pickwick’s first encounter in the prison after the conversation in which the master informed the servant about his decision. Characteristically, the narrator ends this instalment with another cliff-hanger in that we do not get Mr. Pickwick’s definite reaction to Mr. Weller’s announcement that he, too, is now a Fleet prisoner:

”‘Wot I say, Sir,’ rejoined Sam. ‘If it’s forty years to come, I shall be a prisoner, and I’m very glad on it; and if it had been Newgate, it would ha’ been just the same. Now the murder’s out, and, damme, there’s an end on it!’

With these words, which he repeated with great emphasis and violence, Sam Weller dashed his hat upon the ground, in a most unusual state of excitement; and then, folding his arms, looked firmly and fixedly in his master’s face.”

Tristram wrote: "Hello Fellow Curiosities,

This week, we are going to learn how Mr. Pickwick is doing in Fleet Prison and whether his resolution to brave it out is shaken or not. We are also going to meet again an..."

Jails ... prisons, prisoners, a preview of Little Dorrit. You are so right Tristram. There are multiple links between this chapter and the much later novel. Where does one start?

Perhaps it is best to follow just a couple of threads of thought and allow other Curiosities lots of space to add to the conversation. The more I read through PP the more I become convinced that PP was a vast testing ground for Dickens. First, it is clear that Dickens asserted his strong personality from the beginning. Dickens clearly established what he wanted the novel to become. Within that style we are seeing him slowly move from an episodic/picaresque format to one that is much more novelistic. Because this is occurring, the text is much more linked, and thus our characters are evolving and central themes are emerging.

As to Dickens past and how this might effect his writing, I think we see his biographical cloud hovering over all his writing, The PP is his first novel, and this puts it as the closest novel to his earlier experiences as a Parliamentary reporter and law clerk, and, of course, the time his parents and siblings were in debtors’ prison. This chapter shows how a society exists within a jail as much as on the street. This chapter shows us that within a jail, there are predators, prey, and those who retain their passion as well as their principles.

While it is perhaps too much to suggest that this chapter is, in any way, a template for Little Dorrit, I do not think it is an exaggeration to state that the themes and tropes of Dickens that occur in his later novels find their genesis in both Sketches By Boz and The Pickwick Papers.

This week, we are going to learn how Mr. Pickwick is doing in Fleet Prison and whether his resolution to brave it out is shaken or not. We are also going to meet again an..."

Jails ... prisons, prisoners, a preview of Little Dorrit. You are so right Tristram. There are multiple links between this chapter and the much later novel. Where does one start?

Perhaps it is best to follow just a couple of threads of thought and allow other Curiosities lots of space to add to the conversation. The more I read through PP the more I become convinced that PP was a vast testing ground for Dickens. First, it is clear that Dickens asserted his strong personality from the beginning. Dickens clearly established what he wanted the novel to become. Within that style we are seeing him slowly move from an episodic/picaresque format to one that is much more novelistic. Because this is occurring, the text is much more linked, and thus our characters are evolving and central themes are emerging.

As to Dickens past and how this might effect his writing, I think we see his biographical cloud hovering over all his writing, The PP is his first novel, and this puts it as the closest novel to his earlier experiences as a Parliamentary reporter and law clerk, and, of course, the time his parents and siblings were in debtors’ prison. This chapter shows how a society exists within a jail as much as on the street. This chapter shows us that within a jail, there are predators, prey, and those who retain their passion as well as their principles.

While it is perhaps too much to suggest that this chapter is, in any way, a template for Little Dorrit, I do not think it is an exaggeration to state that the themes and tropes of Dickens that occur in his later novels find their genesis in both Sketches By Boz and The Pickwick Papers.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 42 takes us – and Mr. Pickwick – on a journey even deeper into the mysteries and atrocities of Fleet Prison. Here is what happens: Mr. Pickwick wakes up next morning to find himself in the ..."

It is interesting that Pickwick seems quite ready to forgive Jingle but refuses to contemplate any overtures towards Mrs Bardell. Why?

Both Bardell and Jingle have taken advantage of Pickwick, but perhaps Pickwick weights his level of forgiveness based on the degree of public humiliation he feels he has suffered. The Jingle-Job issue, while unpleasant, was only known to a few people. It was a private humiliation, one that clubbing men would be aware of, if not participants in, since their public school days. On the other hand, the Bardell humiliation was intensely public. Played out in a courtroom, Pickwick was openly humiliated and chose to go to prison rather than pay the fine which we are lead to believe he was capable of if he wanted. Is it public humiliation and principle that he found unforgivable? I would say yes.

Throughout the novel to date we have remarked on the fact that he does has a temper but the times it flairs are quickly changed into his usual benevolence. But when he is accused of acting in a manner not befitting a gentleman, there is no forgiveness or humour to be found in his heart.

It is interesting that Pickwick seems quite ready to forgive Jingle but refuses to contemplate any overtures towards Mrs Bardell. Why?

Both Bardell and Jingle have taken advantage of Pickwick, but perhaps Pickwick weights his level of forgiveness based on the degree of public humiliation he feels he has suffered. The Jingle-Job issue, while unpleasant, was only known to a few people. It was a private humiliation, one that clubbing men would be aware of, if not participants in, since their public school days. On the other hand, the Bardell humiliation was intensely public. Played out in a courtroom, Pickwick was openly humiliated and chose to go to prison rather than pay the fine which we are lead to believe he was capable of if he wanted. Is it public humiliation and principle that he found unforgivable? I would say yes.

Throughout the novel to date we have remarked on the fact that he does has a temper but the times it flairs are quickly changed into his usual benevolence. But when he is accused of acting in a manner not befitting a gentleman, there is no forgiveness or humour to be found in his heart.

A few years ago, I read Smollett's Roderick Random, partly also because I knew that Dickens was an avid reader of Smollett and I was curious in what ways the elder's writing style might have influenced the Inimitable. Reading PP now makes me think a lot of Smollett's RR because the structures of both novels are very similar. Both in PP and RR we have an episodic structure, a story of picaresque adventure, with the only difference that Roderick's travels take him abroad, even on a battleship where he partakes in one of England's numerous important sea battles (I can't remember which) and plunge him into numerous predicaments. On the whole, Pickwick's adventures are more light-hearted and genial and he is a much nicer person than Roderick, but what those novels have in common is the episodic structure. What they also have in common is that the second half is dominated by scenes in a debtor's prison. I have the impression that PP's pace is slowing down here and becoming more serious and bitter, and while one can say that RR is quite cynical from the start, Smollett also dwells on the prison days of his hero with more emphasis.

So, interestingly, Dickens might have been influenced by both his personal experience (based on his father's sorry example) and his everyday first-hand material from his days as a parliamentary reporter plus the literary input he got from Tobias Smollett.

So, interestingly, Dickens might have been influenced by both his personal experience (based on his father's sorry example) and his everyday first-hand material from his days as a parliamentary reporter plus the literary input he got from Tobias Smollett.

As to Mr. Pickwick's determination not to give in to Mrs. Bardell's claims, I also have the feeling that it is easier for him to forgive Jingle because in the latter's case, it is obvious that Jingle has come down in the world, having been reduced to sufferings and deprivations, whereas Dodson and Fogg are still on their high horse. I think it is not so much Mrs. Bardell that Mr. Pickwick wants to hold his ground against but rather the two shifty lawyers. By paying his fine and damages to Mrs. Bardell, he would also settle Dodson and Fogg's bill, and this is what he objects to doing.

So, there is the public humiliation and his adherence to principle, but also his grudge against those two shysters, which make him rather go into prison than paying the money he has been condemned to pay.

So, there is the public humiliation and his adherence to principle, but also his grudge against those two shysters, which make him rather go into prison than paying the money he has been condemned to pay.

Tristram wrote:

Tristram wrote:"...it is obvious that Jingle has come down in the world, having been reduced to sufferings and deprivations, whereas Dodson and Fogg..."

I agree. Unlike Jingle/Job, Mrs. Bardell has NOT "come down" herself. She is still content to ride on the arrogant power of her lawyers. I loved reading how Pickwick was softened by encountering Jingle in the prison the way he did. And the passage where he gives some money to them (I'll abbreiviate it):

"Come here, Sir," said Mr Pickwick, trying to look stern, ... "Take that, Sir."

Take what? In the ordinary acceptation of such language, it should have been a blow. ... It was something from Mr Pickwick's waistcoat-pocket, which chinked as it was given into Job's hand..."

I loved how Dickens chose to not be explicit. First, fooling us with a phrase that is associated with throwing a punch. And then, telling us only that it was "something which chinked." It just made me smile.

Tristram wrote: "As to Mr. Pickwick's determination not to give in to Mrs. Bardell's claims, I also have the feeling that it is easier for him to forgive Jingle because in the latter's case, it is obvious that Jing..."

Tristram and Cheryl

Yes. Jingle’s “come down” in society would certainly be a cause for Pickwick’s sympathy. Also, there is no question that Dickens had little time for Bardell’s lawyers.

I wonder if much information exists on how the lawyers that once were associated with Dickens in his youth felt about their portrayal during his career.

Tristram and Cheryl

Yes. Jingle’s “come down” in society would certainly be a cause for Pickwick’s sympathy. Also, there is no question that Dickens had little time for Bardell’s lawyers.

I wonder if much information exists on how the lawyers that once were associated with Dickens in his youth felt about their portrayal during his career.

Tristram wrote: "A few years ago, I read Smollett's Roderick Random, partly also because I knew that Dickens was an avid reader of Smollett and I was curious in what ways the elder's writing style mi..."

Did you like the book?

Did you like the book?

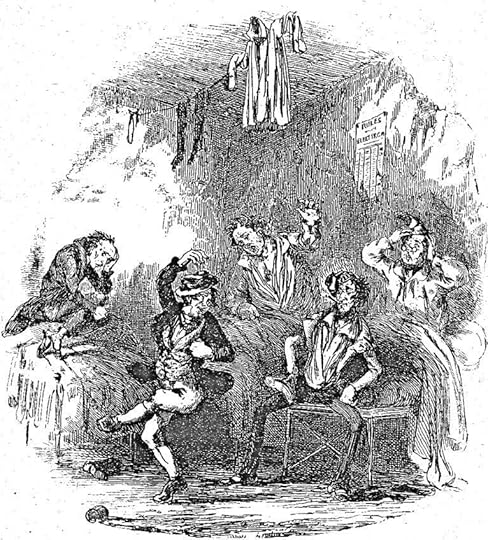

The Warden's Room

Chapter 41

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

With no room as yet assigned to him in the Fleet Prison and as yet unaware that he is at liberty to rent superior quarters and furniture, Samuel Pickwick spends his first night as a prisoner in the Warden's room. The carousing of three inmates awakens him the next morning. Striking a nautical pose, center, is the jocular Mivins, whom his fellow-inmates have dubbed "The Zephyr" on account of his ability to dance the hornpipe. His bearded companion, Smangle, is sitting at the foot of Pickwick's bed. In the bed next to Pickwick's a unnamed drunk applauds Mivins's dancing and warbles a comic song as Smangle encourages The Zephyr to execute further Terpsichorean feats. Fortunately for Pickwick, after daring to challenge Smangle in order to secure his nightcap (which lean, be-whiskered man is about to snatch), he escapes this merry company before learning much more about this merry gang of debauchees. The scene illustrated the morning after Pickwick's induction into the Fleet is this, the "voice" being Smangle's:

"Bravo! Heel over toe — cut and shuffle — pay away at it, Zephyr! I'm smothered if the opera house isn't your proper hemisphere. Keep it up! Hooray!" These expressions, delivered in a most boisterous tone, and accompanied with loud peals of laughter, roused Mr. Pickwick from one of those sound slumbers which, lasting in reality some half-hour, seem to the sleeper to have been protracted for three weeks or a month.

The voice had no sooner ceased than the room was shaken with such violence that the windows rattled in their frames, and the bedsteads trembled again. Mr. Pickwick started up, and remained for some minutes fixed in mute astonishment at the scene before him.

On the floor of the room, a man in a broad-skirted green coat, with corduroy knee-smalls and grey cotton stockings, was performing the most popular steps of a hornpipe, with a slang and burlesque caricature of grace and lightness, which, combined with the very appropriate character of his costume, was inexpressibly absurd. Another man, evidently very drunk, who had probably been tumbled into bed by his companions, was sitting up between the sheets, warbling as much as he could recollect of a comic song, with the most intensely sentimental feeling and expression; while a third, seated on one of the bedsteads, was applauding both performers with the air of a profound connoisseur, and encouraging them by such ebullitions of feeling as had already roused Mr. Pickwick from his sleep.

At the upper right appear the "Rules" of the prison (perhaps real enough, but an interpolation devised by Phiz to comment upon the prevailing anarchy of the place) hanging in tatters, obviously disregarded, as the prisoners make a virtue of their incarceration by drinking at all hours. Perhaps the inmates surrender to the oblivion of alcohol to escape their squalid and unwholesome conditions, but to Pickwick — and to Dickens's readers who are unacquainted with such dismal holes as justice has erected for the defense of property — their slatternly lifestyle is utterly incomprehensible. In Phiz's illustration, Pickwick, hardly crediting his senses, holds his head, the only normative character in the picture. Already, despite the earliness of the hour, one of the inmates is smoking a cigar; shortly, he and his companions will attempt to persuade Pickwick to refresh their drinks and purchase more cigars, alcohol and nicotine being the drugs of choice in this ring of Purgatory.

Thus, Phiz's image of prison life combines the hopelessness of Dickens's description and the debauchery of Hogarth's The Rake's Progress, Scene Seven, "Tom Rakewell in Prison," as the inmates attempt to turn morning into night. Pickwick, then, stands for the normal observances of civilized society and the normal passage of time, including sleeping at night (as his nightcap signifies), while those who have abandoned any hope of release into the normal world beyond the Fleet's walls have given themselves over to a bacchanal existence outside the constraints of real time, and wear the same clothing day in and day out, without respect to season or hour. An apparent invention of the illustrator, the man with an extreme headache on the bed to the left symbolizes the despair to which many in the Fleet abandon themselves.

Detail of Pickwick in bed

Another detail of the rules

With this, the speaker snatched that article of dress from Mr. Pickwick's head

Chapter 41

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

The partying of three inmates in the early morning awakens Pickwick after his first night as a prisoner of the Fleet, where time seems to stand still and drunkards turn night into day. Striking a nautical pose, right, is the jocular Mivins, whom his fellow-inmates have dubbed "The Zephyr" on account of his ability to dance the hornpipe. His bearded companion, Smangle, sitting at the foot of Pickwick's bed (right in the original serial illustration "In The Warden's Room" (July 1837), has already pulled off Pickwick's night-cap in the 1874 revision and is now standing.

In the bed next to Pickwick's, a unnamed drunk (who applauds Mivins's dancing and warbles a comic song in the original engraving from his bed, center) looks almost comatose and can barely come to consciousness as The Zephyr gaily executes the hornpipe at the end of his bed. In Nast's version, which captures a slightly later moment in the episode, Pickwick — now out of bed and in full possession of his faculties, if not his temper — has terminated their dancing, singing, and carousing by threatening to fight with both of the intruders unless they return his cap immediately. The episode begins with the pair of revelers' awakening Pickwick; they then insult him, bully him, and appropriate both his rented space and then his night-cap:

"Bravo! Heel over toe — cut and shuffle — pay away at it, Zephyr! I'm smothered if the opera house isn't your proper hemisphere. Keep it up! Hooray!" These expressions, delivered in a most boisterous tone, and accompanied with loud peals of laughter, roused Mr. Pickwick from one of those sound slumbers which, lasting in reality some half-hour, seem to the sleeper to have been protracted for three weeks or a month.

The voice had no sooner ceased than the room was shaken with such violence that the windows rattled in their frames, and the bedsteads trembled again. Mr. Pickwick started up, and remained for some minutes fixed in mute astonishment at the scene before him.

On the floor of the room, a man in a broad-skirted green coat, with corduroy knee-smalls and grey cotton stockings, was performing the most popular steps of a hornpipe, with a slang and burlesque caricature of grace and lightness, which, combined with the very appropriate character of his costume, was inexpressibly absurd. Another man, evidently very drunk, who had probably been tumbled into bed by his companions, was sitting up between the sheets, warbling as much as he could recollect of a comic song, with the most intensely sentimental feeling and expression; while a third, seated on one of the bedsteads, was applauding both performers with the air of a profound connoisseur, and encouraging them by such ebullitions of feeling as had already roused Mr. Pickwick from his sleep.

Of the telling background details, such as the clothing hanging above the occupants' heads, that add depth to the 1837 original only a page headed by the word "RULES" remains in Phiz's 1873 redrafting. Moreover, in reorienting the illustration from vertical to horizontal and transforming it from fine-lined engraving to heavily-lined woodcut, Phiz has altered the mood of the composition from riotously nightmarish (with Pickwick dismayed by the bacchanal that seems to have broken out in his room) to somnolent as Mivins and Smangle, energized but not necessarily inebriated, contrast the sleepy inmates of the Warden's Room — and Pickwick, devoid of hat and glasses in the 1873 revision, looks nothing like himself. The Zephyr is lighter, more agile, better dressed, and more engaged in his terpsichorean antics in the original; in the 1873 version, we do not see his embroidered "flash" waistcoat, and his figure is heavier; moreover, he shows off his dance steps for Pickwick in the later version, whereas he seems transported to another dimension as he dances in the original 1837 illustration.

In contrast, the pair of revelers who have interrupted Pickwick's sleep are much cowed by a recognizable (although extremely portly) Pickwick in Nast's American Household Edition interpretation (which also includes the "RULES" poster in the background), but are much more realistically modeled in true Sixties style. Presumably, Nast had the following passage in mind when he showed Mivins (right) and Smangle (left) looking much chastened as a bellicose Pickwick improbably challenges the rapscallions to a fist fight:

. . . and then, recapturing his nightcap, [Pickwick] boldly placed himself in an attitude of defence.

"Now," said Mr. Pickwick, gasping no less from excitement than from the expenditure of so much energy, 'come on — both of you — both of you!' With this liberal invitation the worthy gentleman communicated a revolving motion to his clenched fists, by way of appalling his antagonists with a display of science.

It might have been Mr. Pickwick's very unexpected gallantry, or it might have been the complicated manner in which he had got himself out of bed, and fallen all in a mass upon the hornpipe man, that touched his adversaries. Touched they were; for, instead of then and there making an attempt to commit man- slaughter, as Mr. Pickwick implicitly believed they would have done, they paused, stared at each other a short time, and finally laughed outright.

"Well, you're a trump, and I like you all the better for it,' said the Zephyr. "Now jump into bed again, or you'll catch the rheumatics. No malice, I hope?" said the man, extending a hand the size of the yellow clump of fingers which sometimes swings over a glover's door.

"Come on - Both of you - Both of you!"

Chapter 41

Thomas Nast

Text Illustrated:

‘Dear me, I quite forgot,’ replied the other. ‘What will you take, sir? Will you take port wine, sir, or sherry wine, sir? I can recommend the ale, sir; or perhaps you’d like to taste the porter, sir? Allow me to have the felicity of hanging up your nightcap, Sir.’

With this, the speaker snatched that article of dress from Mr. Pickwick’s head, and fixed it in a twinkling on that of the drunken man, who, firmly impressed with the belief that he was delighting a numerous assembly, continued to hammer away at the comic song in the most melancholy strains imaginable.

Taking a man’s nightcap from his brow by violent means, and adjusting it on the head of an unknown gentleman, of dirty exterior, however ingenious a witticism in itself, is unquestionably one of those which come under the denomination of practical jokes. Viewing the matter precisely in this light, Mr. Pickwick, without the slightest intimation of his purpose, sprang vigorously out of bed, struck the Zephyr so smart a blow in the chest as to deprive him of a considerable portion of the commodity which sometimes bears his name, and then, recapturing his nightcap, boldly placed himself in an attitude of defence.

‘Now,’ said Mr. Pickwick, gasping no less from excitement than from the expenditure of so much energy, ‘come on—both of you—both of you!’ With this liberal invitation the worthy gentleman communicated a revolving motion to his clenched fists, by way of appalling his antagonists with a display of science.

It might have been Mr. Pickwick’s very unexpected gallantry, or it might have been the complicated manner in which he had got himself out of bed, and fallen all in a mass upon the hornpipe man, that touched his adversaries. Touched they were; for, instead of then and there making an attempt to commit man–slaughter, as Mr. Pickwick implicitly believed they would have done, they paused, stared at each other a short time, and finally laughed outright.

‘Well, you’re a trump, and I like you all the better for it,’ said the Zephyr. ‘Now jump into bed again, or you’ll catch the rheumatics. No malice, I hope?’ said the man, extending a hand the size of the yellow clump of fingers which sometimes swings over a glover’s door.

‘Certainly not,’ said Mr. Pickwick, with great alacrity; for, now that the excitement was over, he began to feel rather cool about the legs.

Mivins and Smangle

Chapter 41

Sol Eytinge Jr. - 1867

Commentary:

In this fourteenth full-page character study for the last novel in the compact American publication, Eytinge introduces the reader to two of the most minor figures in the Dickens canon — the insolvent debtors whose drunken, early morning revelry rudely awakens Mr. Pickwick after his first night in the Fleet Prison.

The red-nosed, ill-kempt dancer is Mivins, but he prefers to be called "The Zephyr" on account of his terpsichorean prowess. The scene is the Warden's Room, which Pickwick in his nightcap (rear, centre), looking somewhat startled, has rented for his first night as an incarcerated debtor; Smangle, applauding his friend's dance-steps, is to the left, Mivins (The Zephyr) to the right, dancing a hornpipe, as in Phiz's original illustration, "The Warden's Room". The other man present, also mentioned in the text and depicted in the July 1837 steel engraving, is an unnamed reveler.

"Bravo! Heel over toe — cut and shuffle — pay away at it, Zephyr! I'm smothered if the Opera House isn't your proper hemisphere. Keep it up! Hooray!" These expressions, delivered in a most boisterous tone, and accompanied with loud peals of laughter, roused Mr. Pickwick from one of those sound slumbers which, lasting in reality some half–hour, seem to the sleeper to have been protracted for three weeks or a month.

The voice had no sooner ceased than the room was shaken with such violence that the windows rattled in their frames, and the bedsteads trembled again. Mr. Pickwick started up, and remained for some minutes fixed in mute astonishment at the scene before him.

On the floor of the room, a man in a broad–skirted green coat, with corduroy knee–smalls and gray cotton stockings, was performing the most popular steps of a hornpipe, with a slang and burlesque caricature of grace and lightness, which, combined with the very appropriate character of his costume, was inexpressibly absurd. Another man, evidently very drunk, who had probably been tumbled into bed by his companions, was sitting up between the sheets, warbling as much as he could recollect of a comic song, with the most intensely sentimental feeling and expression; while a third, seated on one of the bedsteads, was applauding both performers with the air of a profound connoisseur, and encouraging them by such ebullitions of feeling as had already roused Mr. Pickwick from his sleep.

This last man was an admirable specimen of a class of gentry which never can be seen in full perfection but in such places—they may be met with, in an imperfect state, occasionally about stable–yards and Public–houses; but they never attain their full bloom except in these hot–beds, which would almost seem to be considerately provided by the legislature for the sole purpose of rearing them.

He was a tall fellow, with an olive complexion, long, dark hair, and very thick, bushy whiskers meeting under his chin. He wore no neckerchief, as he had been playing rackets all day, and his Open shirt-collar displayed their full luxuriance. On his head he wore one of the common eighteen-penny French skull–caps, with a gaudy tassel dangling therefrom, very happily in keeping with a common fustian coat. His legs, which, being long, were afflicted with weakness, graced a pair of Oxford–mixture trousers, made to show the full symmetry of those limbs. Being somewhat negligently braced, however, and, moreover, but imperfectly buttoned, they fell in a series of not the most graceful folds over a pair of shoes sufficiently down at heel to display a pair of very soiled white stockings. There was a rakish, vagabond smartness, and a kind of boastful rascality, about the whole man, that was worth a mine of gold.

This figure was the first to perceive that Mr. Pickwick was looking on; upon which he winked to the Zephyr, and entreated him, with mock gravity, not to wake the gentleman.

"Why, bless the gentleman's honest heart and soul!" said the Zephyr, turning round and affecting the extremity of surprise; "the gentleman is awake. Hem, Shakespeare! How do you do, Sir? How is Mary and Sarah, sir? and the dear old lady at home, sir, — eh, sir? Will you have the kindness to put my compliments into the first little parcel you're sending that way, sir, and say that I would have sent 'em before, only I was afraid they might be broken in the wagon, sir?"

"Don't overwhelm the gentlemen with ordinary civilities when you see he's anxious to have something to drink," said the gentleman with the whiskers, with a jocose air. "Why don't you ask the gentleman what he'll take?"

"Dear me, — I quite forgot," replied the other. "What will you take, sir? Will you take port wine, sir, or sherry wine, sir? I can recommend the ale, sir; or perhaps you'd like to taste the porter, sir? Allow me to have the felicity of hanging up your nightcap, sir."

With this, the speaker snatched that article of dress from Mr. Pickwick's head, and fixed it in a twinkling on that of the drunken man, who, firmly impressed with the belief that he was delighting a numerous assembly, continued to hammer away at the comic song in the most melancholy strains imaginable.

Taking a man's nightcap from his brow by violent means, and adjusting it on the head of an unknown gentleman, of dirty exterior, however ingenious a witticism in itself, is unquestionably one of those which come under the denomination of practical jokes. Viewing the matter precisely in this light, Mr. Pickwick, without the slightest intimation of his purpose, sprang vigorously out of bed, struck the Zephyr so smart a blow in the chest as to deprive him of a considerable portion of the commodity which sometimes bears his name, and then, recapturing his nightcap, boldly placed himself in an attitude of defence.

"Now," said Mr. Pickwick, gasping no less from excitement than from the expenditure of so much energy, "come on — both of you — both of you!" With this liberal invitation the worthy gentleman communicated a revolving motion to his clenched fists, by way of appalling his antagonists with a display of science.

It might have been Mr. Pickwick's very unexpected gallantry, or it might have been the complicated manner in which he had got himself out of bed, and fallen all in a mass upon the hornpipe man, that touched his adversaries. Touched they were; for, instead of then and there making an attempt to commit man–slaughter, as Mr. Pickwick implicitly believed they would have done, they paused, stared at each other a short time, and finally laughed outright.

"Well, you're a trump, and I like you all the better for it," said the Zephyr. "Now jump into bed again, or you'll catch the rheumatics. No malice, I hope?" said the man, extending a hand the size of the yellow clump of fingers which sometimes swings over a glover's door.

"Certainly not," said Mr. Pickwick, with great alacrity; for, now that the excitement was over, he began to feel rather cool about the legs.

"Allow me the honour," said the gentleman with the whiskers, presenting his dexter hand, and aspirating the h.

"With much pleasure, sir," said Mr. Pickwick; and having executed a very long and solemn shake, he got into bed again.

"My name is Smangle, sir," said the man with the whiskers.

"Oh," said Mr. Pickwick.

"Mine is Mivins," said the man in the stockings.

We see, for a moment, that more assertive Pickwick, who, thus rudely awakened and deprived of his nightcap as well as his privacy, dares to challenge the be-whiskered Smangle in order to secure the return of his purloined nightcap. The degradation of Pickwick, which Phiz suggests through the room's chaos and in particular through the clothes hanging in the celing, Eytinge only hints at through the dishevelled state of the dancer and his peripatetic audience who have thus suddenly appropriated Mr. Pickwick's room. The scene in Phiz is pure Hogarth, but, transformed into a dual character study in the 1867 woodcut, becomes pure Eytinge. In the 1873 Household Edition's reprise of his 1837 illustration, "With this, the speaker snatched that article of dress from Mr. Pickwick's head", Phiz incorrectly asserts that a second man has been sleeping in the Warden's Room, and interpolates a Turkish fez on the disreputable head of the saucy Smangle. The new style of the sixties, which underscored Phiz's shortcomings as a contemporary illustrator, was towards "photographic realism and academic naturalism" (Cohen); we see in Eytinge's treatment of the scene in the Warden's Room evidence of these sixties traits, and in Phiz's 1873 version a failed attempt to incorporate such elements into what in 1837 was a Cruikshank-like series of caricatures in a theatrical set.

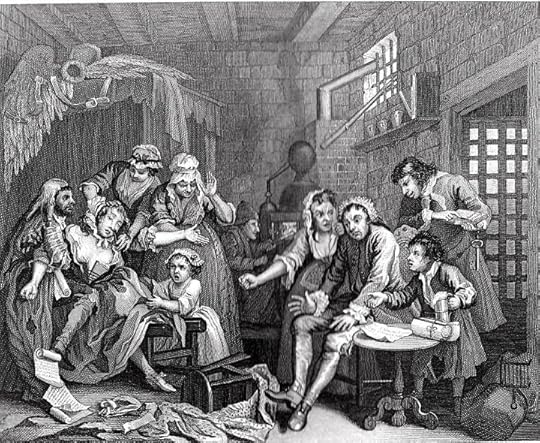

The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet

Chapter 42

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

Despite the comedy that confidence man Alfred Jingle has afforded in the picaresque plot, he is nonetheless a disruptive force — a comic antagonist — whose misdemeanors nevertheless warrant a milder poetic justice than gradually starving to death in a dreary common room in the Fleet Prison. After the prank at the young ladies' boarding school, in which he and his devious servant, Job Trotter, delude Pickwick into believing he must invade the Junonian precincts in order to frustrate Jingle's mercenary designs on a young heiress, the pair of malefactors disappear. However, as one should expect in a picaresque novel, they now resurface. Pickwick, looking for somebody to run errands, encounters these pitiful, scantily clothed subjects of nemesis, Jingle and Trotter, at their lowest ebb, Jingle having pawned his clothing for a small cut of lamb, which Trotter (who is at liberty to come and go, not being an incarcerated debtor himself) is about to deliver to his master in the common room on the poor side. Phiz has rendered neither of them as scantily clad as Dickens's text, but Victorian standards of decency forbade a more faithful treatment of their figures.

Jingle's degradation is reminiscent of that of Hogarth's Tom Rakewell in the seventh "scene" of The Rake's Progress, "The Prison Scene", both are which are set in a "common room" on the "poor" side of a debtors' prison where the inmates can afford neither rent nor "chummage." The once daring protagonist who lived well beyond his means (and, in Jingle's case, by his wits) is now without liberty — or hope. Although Hogarth's Tom has been a naïve dupe, whereas Boz's Jingle is a practiced confidence man, the deeply depressed Tom at least still has most of his clothing, including his wig. Having dined on his wardrobe, Jingle now finds his "cupboard" — like his own person — nearly bare.

The general aspect of the room recalled him to himself at once; but he had no sooner cast his eye on the figure of a man who was brooding over the dusty fire, than, letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment.

Yes; in tattered garments, and without a coat; his common calico shirt, yellow and in rags; his hair hanging over his face; his features changed with suffering, and pinched with famine — there sat Mr. Alfred Jingle; his head resting on his hands, his eyes fixed upon the fire, and his whole appearance denoting misery and dejection!

Near him, leaning listlessly against the wall, stood a strong-built countryman, flicking with a worn — out hunting — whip the top-boot that adorned his right foot; his left being thrust into an old slipper. Horses, dogs, and drink had brought him there, pell-mell. There was a rusty spur on the solitary boot, which he occasionally jerked into the empty air, at the same time giving the boot a smart blow, and muttering some of the sounds by which a sportsman encourages his horse. He was riding, in imagination, some desperate steeplechase at that moment. Poor wretch! He never rode a match on the swiftest animal in his costly stud, with half the speed at which he had torn along the course that ended in the Fleet.

On the opposite side of the room an old man was seated on a small wooden box, with his eyes riveted on the floor, and his face settled into an expression of the deepest and most hopeless despair. A young girl — his little grand — daughter — was hanging about him, endeavouring, with a thousand childish devices, to engage his attention; but the old man neither saw nor heard her. The voice that had been music to him, and the eyes that had been light, fell coldly on his senses. His limbs were shaking with disease, and the palsy had fastened on his mind.

There were two or three other men in the room, congregated in a little knot, and noiselessly talking among themselves. There was a lean and haggard woman, too — a prisoner’s wife — who was watering, with great solicitude, the wretched stump of a dried–up, withered plant, which, it was plain to see, could never send forth a green leaf again — too true an emblem, perhaps, of the office she had come there to discharge.

Such were the objects which presented themselves to Mr. Pickwick’s view, as he looked round him in amazement. The noise of some one stumbling hastily into the room, roused him. Turning his eyes towards the door, they encountered the new–comer; and in him, through his rags and dirt, he recognised the familiar features of Mr. Job Trotter.

"Mr. Pickwick!" exclaimed Job aloud.

"Eh?" said Jingle, starting from his seat. ‘Mr. — ! So it is — queer place — strange things — serves me right — very." Mr. Jingle thrust his hands into the place where his trousers pockets used to be, and, dropping his chin upon his breast, sank back into his chair.

Mr. Pickwick was affected; the two men looked so very miserable. The sharp, involuntary glance Jingle had cast at a small piece of raw loin of mutton, which Job had brought in with him, said more of their reduced state than two hours' explanation could have done. [chapter 42]

Taking his cues from Dickens's descriptions of the various inmates, Phiz has focused on two characters in the center of the composition — Mr. Pickwick in a melodramatic "recognition" pose, and Jingle in a posture suggestive of deep melancholy. However, the illustrator also features the mad huntsman prominently (right), leaning beside the diminutive fireplace (rather than the wall, as in the text). In the background, Phiz has incorporated the knot of three (rather than the text's "two or three") men conversing noisily at the window, and the prisoner's wife (certainly "lean," but not "haggard") tending the desiccated plant at the grimy window (left). He has also filled out the scene with a pair of figures whom Dickens does not describe: a Hogarthesque harridan immediately behind Job Trotter, and a barking Yorkshire terrier at the huntsman's slippered foot. The attentive little dog, trying in vain to engage his distracted master's attention, parallels the granddaughter who fruitlessly tries to rouse her grandfather to an awareness of her and their surroundings. In Phiz's illustration, she expresses deep concern for her grandfather as she takes him by the hand. But the most significant visual interpolation, already noted, is the alcoholic female entering the common room just behind Job Trotter. Her raised fist suggests her impatience with Job's blocking her way, giving her an inner life — Phiz's ironically implied observation is that she is in a hurry, with no place to go.

Details:

Woman watering a dead plant

The melancholy grandfather

The Hogarthian harridan

Here's Hogarth's Tom Rakewell in the seventh "scene" of The Rake's Progress, "The Prison Scene" they talk about.

Letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment

Chapter 42

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary;

As in the original illustration for July 1837, "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet," in Phiz's full-page redrafting for the woodcut medium used exclusively in the Household Edition, Pickwick is startled to discover an uncharacteristically despondent Alfred Jingle in the common room of the Fleet Prison. The 1873 woodcut is a reasonably faithful translation of the 1837 engraving, except, of course, that whereas "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet" is vertical in its orientation, "Letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment" is horizontal, and, as a full-page (framed) illustration, it is reproduced on a much larger scale than the original. The "Tom Rakewell" moment of degradation for Alfred Jingle and the simultaneous moment of recognition for Pickwick realized by both illustrations occurs opposite each picture, in chapter 42:

The general aspect of the room recalled him to himself at once; but he had no sooner cast his eye on the figure of a man who was brooding over the dusty fire, than, letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment.

Yes; in tattered garments, and without a coat; his common calico shirt, yellow and in rags; his hair hanging over his face; his features changed with suffering, and pinched with famine — there sat Mr. Alfred Jingle; his head resting on his hands, his eyes fixed upon the fire, and his whole appearance denoting misery and dejection!

Near him, leaning listlessly against the wall, stood a strong-built countryman, flicking with a worn — out hunting — whip the top-boot that adorned his right foot; his left being thrust into an old slipper. Horses, dogs, and drink had brought him there, pell-mell. There was a rusty spur on the solitary boot, which he occasionally jerked into the empty air, at the same time giving the boot a smart blow, and muttering some of the sounds by which a sportsman encourages his horse. He was riding, in imagination, some desperate steeplechase at that moment. Poor wretch! He never rode a match on the swiftest animal in his costly stud, with half the speed at which he had torn along the course that ended in the Fleet.

On the opposite side of the room an old man was seated on a small wooden box, with his eyes riveted on the floor, and his face settled into an expression of the deepest and most hopeless despair. A young girl — his little grand — daughter — was hanging about him, endeavouring, with a thousand childish devices, to engage his attention; but the old man neither saw nor heard her. The voice that had been music to him, and the eyes that had been light, fell coldly on his senses. His limbs were shaking with disease, and the palsy had fastened on his mind.

There were two or three other men in the room, congregated in a little knot, and noiselessly talking among themselves. There was a lean and haggard woman, too — a prisoner's wife — who was watering, with great solicitude, the wretched stump of a dried-up, withered plant, which, it was plain to see, could never send forth a green leaf again — too true an emblem, perhaps, of the office she had come there to discharge.

Such were the objects which presented themselves to Mr. Pickwick's view, as he looked round him in amazement. The noise of some one stumbling hastily into the room, roused him. Turning his eyes towards the door, they encountered the new-comer; and in him, through his rags and dirt, he recognised the familiar features of Mr. Job Trotter.

"Mr. Pickwick!" exclaimed Job aloud.

"Eh?" said Jingle, starting from his seat. "Mr. — ! So it is — queer place — strange things — serves me right — very." Mr. Jingle thrust his hands into the place where his trousers pockets used to be, and, dropping his chin upon his breast, sank back into his chair.

Mr. Pickwick was affected; the two men looked so very miserable. The sharp, involuntary glance Jingle had cast at a small piece of raw loin of mutton, which Job had brought in with him, said more of their reduced state than two hours' explanation could have done.

Taking his cues from Dickens's descriptions of the various inmates, Phiz has focused on two characters in the center of the composition — Mr. Pickwick in a melodramatic "recognition" pose (toned down somewhat in the 1873 composition), and Jingle sitting on a stool (in 1873, a chair) with a vacant gaze and in a slumping posture suggestive of deep melancholy, one slippered foot on the fender. However, the illustrator also features the mad huntsman prominently (right), leaning beside the diminutive fireplace (rather than the wall, as in the text). In the background, Phiz has incorporated the knot of three (rather than the text's "two or three") men conversing noisily at the window, and the prisoner's wife (certainly "lean," but not "haggard") tending the dessicated plant at the grimy window (left). He has also filled out the scene with a pair of figures whom Dickens does not describe: a Hogarthesque harridan (who is not nearly so unpleasant in the 1873 revision) immediately behind Job Trotter, and — in the original but not in the woodcut — a barking Yorkshire terrier at the huntsman's slippered foot (which becomes a pair of Wellington boots in the 1873 revision).

In the original plate, considerable subtlety of commentary is involved in Phiz's positioning of the attentive little dog, trying in vain to engage his distracted master's attention, for he parallels the granddaughter (left, a mere careworn child in the 1837 engraving, but a respectably dressed young woman in the 1873 woodcut) who fruitlessly tries to rouse her grandfather to an awareness of her and their surroundings. In both of these Phiz illustrations, she expresses tender concern for her grandfather as she attempts to take him by the hand. But the most significant visual interpolation, already noted, is the alcoholic female entering the common room just behind Job Trotter. Her raised fist suggests her impatience with Job's blocking her way, giving her an inner life — Phiz's ironically implied observation is that she is in a hurry, with no place to go. The two illustrations, distinguished primarily by orientation and medium, differ too in a more subtle way in that the earlier engraving is an homage to the "progresses" of eighteenth-century narrative-pictorial satirist William Hogarth (1697-1764) — such as the six engravings that make up the unfortunate trajectory of Moll Hackabout, A Harlot's Progress (1732), and Marriage A-la-Mode (1745), whereas the remodeling of the figures into a more realistic Sixties style seems to have resulted in a loss of Hogarthian vigor, as the 1873 woodcut derives from Phiz's 1837 "Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet" rather than directly from, for example, "Tom Rakewell in Prison" in A Rake's Progress (1735). The slender figures, the social satire, the view of London low-life and the criminal underclass, the satire of social institutions such as the Church and the law, and the embedding of textual and visual symbols that serve as subtle commentaries on the characters and situations depicted — these features are all associated with the engravings and paintings of William Hogarth, the eighteenth-century English artist noted for his satirical narrative paintings and engravings that satirize contemporary vices and affectations. In his old age, Hablot Knight Browne seems to have lost his taste for social satire, as, for example, his depicting the "mad huntsman" in boots in the 1873 woodcut rather than a boot and a slipper. Although the Household Edition illustration is sharper, its space and figures more clearly defined, it lacks the exuberance of the original, as if it has lost its moral "inner life" because it no longer graphs the decay of the modern European city as Hogarth had done repeatedly.

Peter wrote: "It is interesting that Pickwick seems quite ready to forgive Jingle but refuses to contemplate any overtures towards Mrs Bardell. Why?

I thought it was because she was a woman. Wouldn't it be easier for a man to forgive a man who has embarrassed him than by a woman back then? I would think it still is at places around here.

I thought it was because she was a woman. Wouldn't it be easier for a man to forgive a man who has embarrassed him than by a woman back then? I would think it still is at places around here.

Oh, Sam!!!

Oh, Sam!!!This is the first time I've cheated at the end of an installment and read on. I yanked myself away after a sentence or two, but I couldn't just leave Sam there unanswered by Pickwick.

I was happy to see Jingle again, but unhappy that he's had a comeuppance. I feel Dickens yielded to conventional morality by bringing him down and making him so remorseful for his sins. And yes, I know he deserves it (poor Miss Rachael!), but it's unrealistic that he's so thoroughly lost his scoundrel self, and I can't help but wish he'll get a little bounce back at some point in the future, though it doesn't look likely now.

At least he still talks in fragments.

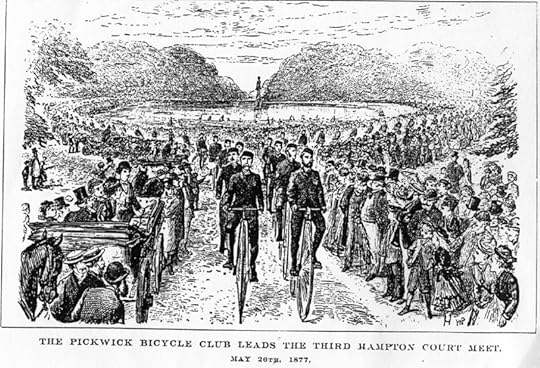

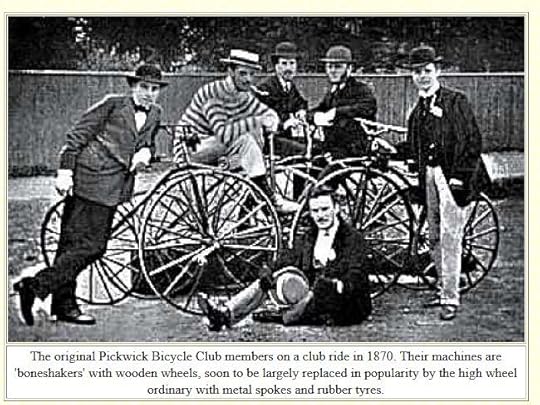

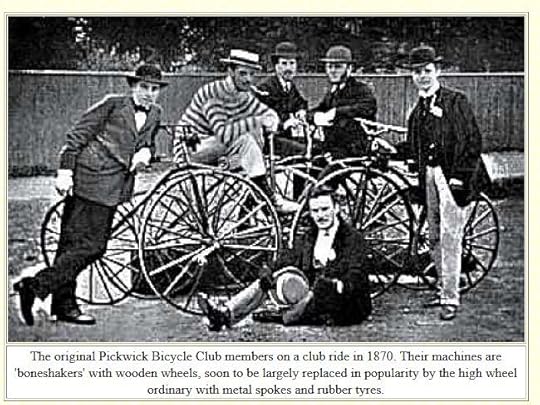

The Pickwick Bicycle Club

Established 1870

The Pickwick Bicycle Club was formed on the 22nd June, 1870, when six cycling enthusiasts met at the Downs Hotel, Hackney Downs, East London, and decided to form themselves into a bicycle club. As the formation coincided with the death of Charles Dickens the name "Pickwick" was chosen in honour of the novelist. From that time onwards the Pickwick Bicycle Club has an unbroken history as an active cycling organisation and in the worthwhile task of spreading fellowship and conviviality.

The Pickwick Bicycle Club is not only the oldest cycling club in the world but it is also the oldest Dickensian Association.

Its present-day activities, whilst still maintaining its cycling traditions, provides the opportunity for setting aside the day-today worries, and meeting in an atmosphere of conviviality and good fellowship.

The Pickwick Bicycle Club

The year 2010, sees the 140th anniversary of the oldest surviving bicycle club in the world - the Pickwick Bicycle Club.

The Anfield Bicycle Club, founded in 1879, proudly claims the same heritage and unlike the Pickwick Bicycle Club is still active as a club for cycling. The Pickwick BC is now predominantly a luncheon club with only the demise of an existing member allowing entry.

As a reminder of days long gone, we have this extract, describing the early days of the Pickwick BC, from the 1928 year book of the Liverpool District Association of the Cyclists Touring Club.

We know nothing of the author, J Foxley Norris, apart from the fact that he was born about 12 years before the Pickwick BC was founded.

Early Cycling by J Foxley Norris

(Article in 1928 Yearbook of the Liverpool District Association, CTC)

On the 22 June 1870 six pioneers of the bicycle (or velocipede) movement met at the Downs Hotel Hackney Downs, London, and formed themselves into a bicycle club. The question by what name they would be known was discussed and since Charles Dickens had just died, the title of 'Pickwick' was chosen, each member to bear a selected sobriquet from the varied characters abounding in the pages of Pickwick Papers.

It was from such a modest beginning that a famous cycling club has evolved, and a life of fifty eight years has not dimmed its lustre or reputation, but it continues its active old age with about two hundred members.

The history of the Pickwick BC is an epitome of cycling from its earliest days. The usual runs in the early 1870s were about ten miles out, and a radius of 20 miles would well constitute a Sunday or weekend fixture. Such riding may seem trivial to the rider of 1928, but he will be reminded of the weight of the 'boneshaker' - 60lbs with its wooden wheels, iron tyres, and the villainous character of the road surfaces. Nor must he be contemptuous when he is informed that the first race proposed in October 1872 to Huntington was abandoned as the weather was unsuitable.

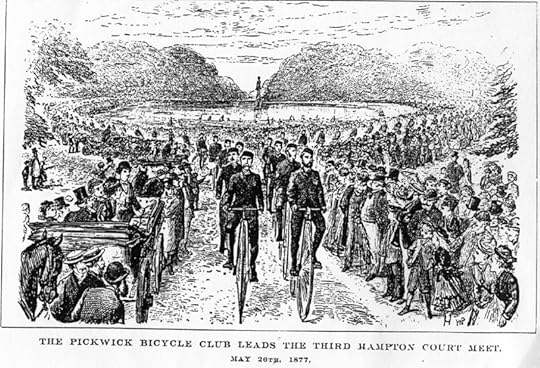

A lengthy account of an Easter Tour by the Pickwick and Surrey BC appeared in the 'Daily News' of April 21st 1873. The party is recorded as stopping the night at Margate, Rye and Brighton. In the same year the PBC organised a 20 mile race to Ware, which was won on a 48'' wheel in 1hr 28mins.

An interesting race on Aug 9th 1873 was promoted in the Royal Surrey Gardens. The track was improvised, being composed of boards laid down wherever a way could be contrived around and about the paths, bushes, flower beds and the varied landscape effects of the old gardens, as I well remember them. The track, such as it was of about eight laps to the mile, was a twister; and the riding colours - scarlet, green, blue, pink and yellow - whilst sounding gaudy, were only bands of ribbon tied around the arms. Fancy trying a similar race now!

On the 10th September 1873 the Surrey BC held a race meeting at the Oval, consisting of a four miles, and a one mile handicap, and a slow race of 100yds. In the Field of 17th June 1876 a notable ride is recorded by H Stanley Thorpe of the Pickwick BC. The two hundred miles from London to York was accomplished on a 50'' Ariel weighing 66lbs under 23 hrs. Towards the end the rider increased his speed to ten miles per hour.

The Daily News of October 15th 1874 contained an interesting account of a tour of the Lake District by Messrs 'Pickwick', Tracy Tupman, Bill Stumps and Tom Smart. About a fortnight of adventure is recorded, and we are told the riders were perforce supplied with dry clothes at the Saracen's Head, Dunstable, and were sumptuously entertained by the ex-Mayor of Derby

In 1874 again, David Stanton, publican and professional cyclist, essayed to ride from Bath to London on a 56'' wheel in eight hours. He declared that at Colnbrook men threw sledge hammers at him, and stopped him finishing.

Reading these last mentioned events fired my ambition to become a bicycler. I bought Charles Spencer's book published in 1870, The Bicycle its Use and Action, hired a boneshaker by the hour and after repeated tumbles in my first hour, acquired my balance. On my sixth hiring I rode to Enfield and back, about fifteen miles, having for the first and last time an attack of cramp in my thigh. Shortly afterwards I purchased a 'Gentleman', 48'' wheel, made by the Coventry Machinists Company, and joined the Pickwick Bicycle Club

That was fifty three years ago. I have ridden about fifty bicycles of all sorts since. In the last six months, at the age of seventy I have ridden more that 5,000 miles. What shall I say? Go! and do likewise.

J Foxley Norris, 1928

From Ken Barker, once president of the club:

It is probable that the Pickwick Bicycle Club, as an organisation, is unique in the world.

There are many clubs that are supported by the leisure and sporting interests of their members or by the numerous literary associations, but a combination of both such interests is a different matter. I know of none similar to ours.

Membership is considered a privilege and does impose certain obligations. High amongst these are good manners and good fellowship. The essence of the Club is that it is private and publicity is neither sought nor welcomed. Other than in the early years (when all members would have been familiar with the work of Charles Dickens and would have known the Pickwick Papers in detail) the emphasis has been on cycling, rather than reading. The early records detail weekly runs over much of the Home Counties, but it is a regrettable fact that since the Second World War, interest in this respect has diminished, so that now only a handful of members enjoy the occasional spin. Similarly, it is unfortunate that interest in the books of Charles Dickens has lessened. His stories are still widely used throughout the world in film and television, but gone are the days when he had as many readers as did the daily papers.

This does not prevent the club from trying, in as many ways as it can, to encourage his traditions. A Dickensian atmosphere is maintained at its meetings and members are expected to know the qualities and deeds of their sobriquet. It has been possible to extract the names of over two hundred characters to provide a sobriquet for each of those invited to join.

The Club values and tries to preserve the traditions of the past. Members gather twice a year, without any strong desire to put the world to rights, and there seems no reason to believe they should not continue to do so long into the future.

Ken Barker (The Shepherd) Past President

http://www.pickwickbc.org.uk/Boys-Own...

Established 1870

The Pickwick Bicycle Club was formed on the 22nd June, 1870, when six cycling enthusiasts met at the Downs Hotel, Hackney Downs, East London, and decided to form themselves into a bicycle club. As the formation coincided with the death of Charles Dickens the name "Pickwick" was chosen in honour of the novelist. From that time onwards the Pickwick Bicycle Club has an unbroken history as an active cycling organisation and in the worthwhile task of spreading fellowship and conviviality.

The Pickwick Bicycle Club is not only the oldest cycling club in the world but it is also the oldest Dickensian Association.

Its present-day activities, whilst still maintaining its cycling traditions, provides the opportunity for setting aside the day-today worries, and meeting in an atmosphere of conviviality and good fellowship.

The Pickwick Bicycle Club

The year 2010, sees the 140th anniversary of the oldest surviving bicycle club in the world - the Pickwick Bicycle Club.

The Anfield Bicycle Club, founded in 1879, proudly claims the same heritage and unlike the Pickwick Bicycle Club is still active as a club for cycling. The Pickwick BC is now predominantly a luncheon club with only the demise of an existing member allowing entry.

As a reminder of days long gone, we have this extract, describing the early days of the Pickwick BC, from the 1928 year book of the Liverpool District Association of the Cyclists Touring Club.

We know nothing of the author, J Foxley Norris, apart from the fact that he was born about 12 years before the Pickwick BC was founded.

Early Cycling by J Foxley Norris

(Article in 1928 Yearbook of the Liverpool District Association, CTC)

On the 22 June 1870 six pioneers of the bicycle (or velocipede) movement met at the Downs Hotel Hackney Downs, London, and formed themselves into a bicycle club. The question by what name they would be known was discussed and since Charles Dickens had just died, the title of 'Pickwick' was chosen, each member to bear a selected sobriquet from the varied characters abounding in the pages of Pickwick Papers.

It was from such a modest beginning that a famous cycling club has evolved, and a life of fifty eight years has not dimmed its lustre or reputation, but it continues its active old age with about two hundred members.

The history of the Pickwick BC is an epitome of cycling from its earliest days. The usual runs in the early 1870s were about ten miles out, and a radius of 20 miles would well constitute a Sunday or weekend fixture. Such riding may seem trivial to the rider of 1928, but he will be reminded of the weight of the 'boneshaker' - 60lbs with its wooden wheels, iron tyres, and the villainous character of the road surfaces. Nor must he be contemptuous when he is informed that the first race proposed in October 1872 to Huntington was abandoned as the weather was unsuitable.

A lengthy account of an Easter Tour by the Pickwick and Surrey BC appeared in the 'Daily News' of April 21st 1873. The party is recorded as stopping the night at Margate, Rye and Brighton. In the same year the PBC organised a 20 mile race to Ware, which was won on a 48'' wheel in 1hr 28mins.

An interesting race on Aug 9th 1873 was promoted in the Royal Surrey Gardens. The track was improvised, being composed of boards laid down wherever a way could be contrived around and about the paths, bushes, flower beds and the varied landscape effects of the old gardens, as I well remember them. The track, such as it was of about eight laps to the mile, was a twister; and the riding colours - scarlet, green, blue, pink and yellow - whilst sounding gaudy, were only bands of ribbon tied around the arms. Fancy trying a similar race now!

On the 10th September 1873 the Surrey BC held a race meeting at the Oval, consisting of a four miles, and a one mile handicap, and a slow race of 100yds. In the Field of 17th June 1876 a notable ride is recorded by H Stanley Thorpe of the Pickwick BC. The two hundred miles from London to York was accomplished on a 50'' Ariel weighing 66lbs under 23 hrs. Towards the end the rider increased his speed to ten miles per hour.

The Daily News of October 15th 1874 contained an interesting account of a tour of the Lake District by Messrs 'Pickwick', Tracy Tupman, Bill Stumps and Tom Smart. About a fortnight of adventure is recorded, and we are told the riders were perforce supplied with dry clothes at the Saracen's Head, Dunstable, and were sumptuously entertained by the ex-Mayor of Derby

In 1874 again, David Stanton, publican and professional cyclist, essayed to ride from Bath to London on a 56'' wheel in eight hours. He declared that at Colnbrook men threw sledge hammers at him, and stopped him finishing.

Reading these last mentioned events fired my ambition to become a bicycler. I bought Charles Spencer's book published in 1870, The Bicycle its Use and Action, hired a boneshaker by the hour and after repeated tumbles in my first hour, acquired my balance. On my sixth hiring I rode to Enfield and back, about fifteen miles, having for the first and last time an attack of cramp in my thigh. Shortly afterwards I purchased a 'Gentleman', 48'' wheel, made by the Coventry Machinists Company, and joined the Pickwick Bicycle Club

That was fifty three years ago. I have ridden about fifty bicycles of all sorts since. In the last six months, at the age of seventy I have ridden more that 5,000 miles. What shall I say? Go! and do likewise.

J Foxley Norris, 1928

From Ken Barker, once president of the club:

It is probable that the Pickwick Bicycle Club, as an organisation, is unique in the world.

There are many clubs that are supported by the leisure and sporting interests of their members or by the numerous literary associations, but a combination of both such interests is a different matter. I know of none similar to ours.

Membership is considered a privilege and does impose certain obligations. High amongst these are good manners and good fellowship. The essence of the Club is that it is private and publicity is neither sought nor welcomed. Other than in the early years (when all members would have been familiar with the work of Charles Dickens and would have known the Pickwick Papers in detail) the emphasis has been on cycling, rather than reading. The early records detail weekly runs over much of the Home Counties, but it is a regrettable fact that since the Second World War, interest in this respect has diminished, so that now only a handful of members enjoy the occasional spin. Similarly, it is unfortunate that interest in the books of Charles Dickens has lessened. His stories are still widely used throughout the world in film and television, but gone are the days when he had as many readers as did the daily papers.

This does not prevent the club from trying, in as many ways as it can, to encourage his traditions. A Dickensian atmosphere is maintained at its meetings and members are expected to know the qualities and deeds of their sobriquet. It has been possible to extract the names of over two hundred characters to provide a sobriquet for each of those invited to join.

The Club values and tries to preserve the traditions of the past. Members gather twice a year, without any strong desire to put the world to rights, and there seems no reason to believe they should not continue to do so long into the future.

Ken Barker (The Shepherd) Past President

http://www.pickwickbc.org.uk/Boys-Own...

Kim wrote: "The Pickwick Bicycle Club

Established 1870