The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP chapters 27 - 29

Chapter 28

I think I’ll start at the end of this chapter. The last paragraph begins with the sentence “But bless our editorial heart, what a long chapter we have been betrayed into! We had quite forgotten all such petty restrictions as chapters, we solemnly declare.” Another of Dickens’s interesting and revealing authorial interpolations. I will do my best to squeeze the accordion of length for my comments.

The chapter begins on the 22nd day of December and we are on our way to Dingley Dell to celebrate Christmas with the Wardles and attend a wedding. In yet an author’s interpolation we read that “We wrote these words now, many miles from the spot at which, year after year, we met on that day, a merry and joyous circle. Many hearts that throbbed so gaily then, have ceased to beat; many of the looks than shone so brightly then have ceased to glow;” In these words we can gain further understanding and insight into the full title of the novel - The Posthumous Papers Of The Pickwick Club. It is interesting that a novelist as young as Dickens was able to see and then project how a wedding and the season of Christmas are both imbued with both great joy and still contain what Thomas Gray called “th’ inevitable hour.”

Thoughts

Have there been earlier incidents or events in the novel that have contained and combined both the happiness of life and its sorrows? If so, to what extent does this style of Dickens help enhance the novel’s effectiveness and enjoyment?

As perhaps a precursor to the amount of food and beverage that will be consumed over the holiday we read the comedic antics of Sam stuffing a cod-fish into the coach. Is the coach meant to be symbolic of a person’s mouth? When Sam asks the fat boy if he ever drinks the fat boy responds “I like eating, better.” Still, the fat boy is quite happy to enjoy a drink with Sam before they head off to Dingley Dell. The coach trip is a chilly one, but with shawls pulled up and coat collars adjusted, off our Pickwickians go. Sam proceeds to drive the cart to Dingley Dell as the fat boy has fallen asleep. Again. Does the fat boy eat more often than he sleeps? Pickwick and his friends take a brisk winter’s walk and had such fun that it would “induce a couple of elderly gentlemen, in a lonely field, to take off their great-coats and play leap-frog in pure lightness of heart and gaiety.” Mr Wardle greets the Pickwickians and we read that “[a]ll ... was very snug and pleasant.” The wedding proceeds the next day without incident “[a]nd all the Pickwickians were in most blooming array.” I kept waiting for something horrendous to ruin everything in this chapter, but I waited in vain. Perhaps the only slight bump was the observation that Sam was very popular and was “as much at home as if he had been born on the land.” One can never fully escape the class system.

Thoughts

Were you waiting for a great crisis, the arrival of Jingle, or any other discordant event to ruin the merriment of the chapter? Why/why not?

A Wellerism

As the fat boy and Sam set out the mince pies for the wedding reception we are treated to another Wellerism when Sam says “we look compact and comfortable, as the father said ven he cut the little boy’s head off, to cure him of squintin’.”

Wardle and Pickwick toast each other, and more joy is spread amongst the guests. Needless to say, food and drink are the most popular residents of the dining table. For the original readers of the novel who were poor, there must have been rumblings in their tummies as they read, or heard read, about so much food. More toasts follow, more food follows; I think I’ve already gained weight just reading this chapter.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of the evening occurred when Mr Pickwick appeared without his gaiters. This was the first time he had done so in the memory of his oldest friends. Now, I had no idea what that signified. Fortunately, Mr Wardle explained it to me. It means Mr Pickwick is planning to dance. Just as the music begins, it is stopped. Where is Arabella Allen? Where is Mr Winkle? Ah, there they are, emerging from a corner blushing with red faces. Is there yet another romance blooming? Time will tell. The dancing begins again and soon Pickwick tires and the newly-married couple retire from the scene. We then get a short tale told by Sam. Sam tells a tale of a man, his expensive watch, its sturdy chain, and the pickpockets who lusted after the watch. One pickpocket finally does steal the watch by butting into the corpulent man’s stomach. The moral of this rather loosely structured and tatty tale is don’t eat too much or a bump to your stomach will ruin your digestion. While this tale is brief, it is still too long. Indeed, there may be humour in it but it was rather fruitless to me. - pun intended.

Some Christmas kissing follows as well as games and then the entire household, including the servants, gather and, as Mr Wardle tells us, “[o]ur invariable custom ... Everyone sits down with us on Christmas Eve, as you see them now - servants and all; and here we wait, until the clock strikes twelve, to usher Christmas in, and beguile the time with forfeits and old stories.” Ah, it appears we are approaching a Christmas story.

It is important to note that The Pickwick Papers precedes A Christmas Carol by almost ten years. I will say nothing about the Hablot K. Browne illustration for this chapter until Kim posts it, but I will suggest that the Wardle Christmas celebration appears to be a direct precursor to the grand Fezziwig party that will occur in A Christmas Carol.

Thoughts

To what extent did you find this chapter contains elements of the Fezziwig party in ACC?

I am avoiding comment on the song printed in this chapter, the lyrics of which are there for all of us to enjoy. My mother often told me that if I had nothing nice to say about a person or situation then I should say nothing. My mother was the wisest person I have ever known. Notice the title of the song. Yes, it would be logical to call a song sung at Christmas “A Christmas Carol”. I feel the ghost of a novella yet to be haunting us in this chapter. The chapter ends with the promise of a Christmas story concerning goblins and a man named Gabriel Grub. Ghost stories at Christmas were a staple of the Victorian reading public and Dickens is not going to deny his readers a ghost story. And so the chapter ends with an apology from the author for being rather long-winded.

I think I’ll start at the end of this chapter. The last paragraph begins with the sentence “But bless our editorial heart, what a long chapter we have been betrayed into! We had quite forgotten all such petty restrictions as chapters, we solemnly declare.” Another of Dickens’s interesting and revealing authorial interpolations. I will do my best to squeeze the accordion of length for my comments.

The chapter begins on the 22nd day of December and we are on our way to Dingley Dell to celebrate Christmas with the Wardles and attend a wedding. In yet an author’s interpolation we read that “We wrote these words now, many miles from the spot at which, year after year, we met on that day, a merry and joyous circle. Many hearts that throbbed so gaily then, have ceased to beat; many of the looks than shone so brightly then have ceased to glow;” In these words we can gain further understanding and insight into the full title of the novel - The Posthumous Papers Of The Pickwick Club. It is interesting that a novelist as young as Dickens was able to see and then project how a wedding and the season of Christmas are both imbued with both great joy and still contain what Thomas Gray called “th’ inevitable hour.”

Thoughts

Have there been earlier incidents or events in the novel that have contained and combined both the happiness of life and its sorrows? If so, to what extent does this style of Dickens help enhance the novel’s effectiveness and enjoyment?

As perhaps a precursor to the amount of food and beverage that will be consumed over the holiday we read the comedic antics of Sam stuffing a cod-fish into the coach. Is the coach meant to be symbolic of a person’s mouth? When Sam asks the fat boy if he ever drinks the fat boy responds “I like eating, better.” Still, the fat boy is quite happy to enjoy a drink with Sam before they head off to Dingley Dell. The coach trip is a chilly one, but with shawls pulled up and coat collars adjusted, off our Pickwickians go. Sam proceeds to drive the cart to Dingley Dell as the fat boy has fallen asleep. Again. Does the fat boy eat more often than he sleeps? Pickwick and his friends take a brisk winter’s walk and had such fun that it would “induce a couple of elderly gentlemen, in a lonely field, to take off their great-coats and play leap-frog in pure lightness of heart and gaiety.” Mr Wardle greets the Pickwickians and we read that “[a]ll ... was very snug and pleasant.” The wedding proceeds the next day without incident “[a]nd all the Pickwickians were in most blooming array.” I kept waiting for something horrendous to ruin everything in this chapter, but I waited in vain. Perhaps the only slight bump was the observation that Sam was very popular and was “as much at home as if he had been born on the land.” One can never fully escape the class system.

Thoughts

Were you waiting for a great crisis, the arrival of Jingle, or any other discordant event to ruin the merriment of the chapter? Why/why not?

A Wellerism

As the fat boy and Sam set out the mince pies for the wedding reception we are treated to another Wellerism when Sam says “we look compact and comfortable, as the father said ven he cut the little boy’s head off, to cure him of squintin’.”

Wardle and Pickwick toast each other, and more joy is spread amongst the guests. Needless to say, food and drink are the most popular residents of the dining table. For the original readers of the novel who were poor, there must have been rumblings in their tummies as they read, or heard read, about so much food. More toasts follow, more food follows; I think I’ve already gained weight just reading this chapter.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of the evening occurred when Mr Pickwick appeared without his gaiters. This was the first time he had done so in the memory of his oldest friends. Now, I had no idea what that signified. Fortunately, Mr Wardle explained it to me. It means Mr Pickwick is planning to dance. Just as the music begins, it is stopped. Where is Arabella Allen? Where is Mr Winkle? Ah, there they are, emerging from a corner blushing with red faces. Is there yet another romance blooming? Time will tell. The dancing begins again and soon Pickwick tires and the newly-married couple retire from the scene. We then get a short tale told by Sam. Sam tells a tale of a man, his expensive watch, its sturdy chain, and the pickpockets who lusted after the watch. One pickpocket finally does steal the watch by butting into the corpulent man’s stomach. The moral of this rather loosely structured and tatty tale is don’t eat too much or a bump to your stomach will ruin your digestion. While this tale is brief, it is still too long. Indeed, there may be humour in it but it was rather fruitless to me. - pun intended.

Some Christmas kissing follows as well as games and then the entire household, including the servants, gather and, as Mr Wardle tells us, “[o]ur invariable custom ... Everyone sits down with us on Christmas Eve, as you see them now - servants and all; and here we wait, until the clock strikes twelve, to usher Christmas in, and beguile the time with forfeits and old stories.” Ah, it appears we are approaching a Christmas story.

It is important to note that The Pickwick Papers precedes A Christmas Carol by almost ten years. I will say nothing about the Hablot K. Browne illustration for this chapter until Kim posts it, but I will suggest that the Wardle Christmas celebration appears to be a direct precursor to the grand Fezziwig party that will occur in A Christmas Carol.

Thoughts

To what extent did you find this chapter contains elements of the Fezziwig party in ACC?

I am avoiding comment on the song printed in this chapter, the lyrics of which are there for all of us to enjoy. My mother often told me that if I had nothing nice to say about a person or situation then I should say nothing. My mother was the wisest person I have ever known. Notice the title of the song. Yes, it would be logical to call a song sung at Christmas “A Christmas Carol”. I feel the ghost of a novella yet to be haunting us in this chapter. The chapter ends with the promise of a Christmas story concerning goblins and a man named Gabriel Grub. Ghost stories at Christmas were a staple of the Victorian reading public and Dickens is not going to deny his readers a ghost story. And so the chapter ends with an apology from the author for being rather long-winded.

Chapter 29

In this chapter Dickens gives us yet another story. In this case, the story is somewhat different. In “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton” the story is no longer part of a larger chapter but serves as the entire chapter. I wonder how this will effect the chapter’s story, its readers, and the structure of the entire novel, and the expectations of the readers going forward. Will future tales be much longer, will they reflect more closely and comment upon the larger text? The Victorians liked their dose of ghosts and goblins and so this story fits very comfortably into the Christmas celebrations at Dingley Dell and the literary tradition in England.

The tone and setting are perfect for a story. Indeed, the opening is perhaps the best possible one:

“In an old abbey town, down in this part of the country, a long, long while ago - so long that the story must be a true one, because our great grandfathers implicitly believed it - “

We read that in this abbey town is found a sexton and grave-digger named Gabriel Grub. What a great name, one of Dickens’s best. Tristram has pointed out the word aptronym and how Dickens incorporates aptronyms in his work. Gabriel. The angel Gabriel is most often portrayed as being God’s messenger. Grub. What a perfect name for a man who digs graves. Gabriel Grub. With the assigning of this name to the central character of the story we are given both the spiritual and the secular, the immortal and the very essential concept of mortality. The theme of this story will be most interesting as Dickens will, no doubt, braid these two elements together.

Gabriel Grub we are told “was an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow - a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself, and an old wicker bottle ... .” One Christmas Eve he “shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards the old churchyard; for he had got a grave to finish by next morning, and feeling very low, he thought it might raise his spirits, perhaps, if he went on with his work at once.” As he passes through the town he notices the lights of blazing fires and smells the savoury aroma of cooking, but takes no joy in such observations; rather, he takes consolation in thoughts of illness and death. Such thoughts put him in a happy frame of mind. In one instance Grub finds joy in rapping a boy over the head who has been singing.

Thoughts

Did you find the style of beginning this chapter with a story disruptive given the format of earlier stories, or did you find it an effective style? Why?

Why might the telling of a ghost or goblin story have been so enjoyable in the Victorian age?

Gabriel arrives at the churchyard and settles in to dig a grave. At times he sits on a flat tombstone and draws forth his wicker bottle for a drink and enjoys a private joke - “[a] coffin at Christmas! A Christmas Box.” Well, perhaps it’s a good joke when told in context of a graveyard. He follows this up with a hearty “Ho! ho.” But wait! He hears a response of “Ho! ho! ho” from behind him. Lo and behold, “seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once was no being of this world.” It was a goblin who appeared as if he had sat on the same tombstone for hundreds of years. The goblin asks “What man wanders among graves and churchyards on such a night as this? To this question “a wild chorus of voices” screams, in response, “Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!” Gabriel is terrified. The goblin tells Gabriel that the chorus of voices wants him. Why?

The goblin tells Gabriel:

“we know the man with the sulky face and grim scowl, that comes down the street tonight, throwing his evil looks at the children, and grasping his burying spade the tighter. We know the man who struck the boy in the envious malice of his heart, because the boy could be merry, and he could not. We know him, we know him.”

With this the goblin lets out a loud laugh and stands upon his head and does a somersault with extraordinary agility. Then, troops of goblins begin playing leap-frog with the tombstones. The church organ is heard to play louder and louder. Gabriel’s brain whirls, and he finally sinks “through the earth.” A goblin pours a blazing liquid down his throat and Gabriel hears that he will be forced to see “a few of the pictures from our own great storehouse!”

Thoughts

Wow! There is so much going on, so many possible connections, so many speculations we could explore.

Is it me or does the chief goblin remind you a bit of Quilp?

Do you think this goblin, if he does remind you of Quilp, will turn out to be malevolent or benevolent? Why?

At this point in the tale, to what extent do you fear for the final fate of Gabriel?

We encounter a series of instances where there are “mysterious voices” that chant Gabriel’s name. To what extent could these voices be seen as Gabriel’s own conscious slowly emerging from the depths of his being?

At this point we learn that the goblins will show Gabriel, “the man of misery and gloom, a few of the pictures from our own storehouse!” And with this, Gabriel is introduced to the first vision of a poor but proud and happy family who have one of their children near death. The other children of the family crowd around his little bed. The child is discovered dead but his siblings are comforted by the thought that he is now an Angel looking down on his family from heaven. The scene changes and the father and mother of the family are now “old and helpless” but still the parents and the remaining children are content as they crowd around the fireplace “and told and listened to old stories of earlier and bygone days.” In time the parents die, but the few that survive them: “knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it, with their tears ... [but] they knew that they should one day meet again;” Dickens’s Christmas book “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain” evolves the concept of how one’s good memories can keep a person’s world green.

Gabriel seems a bit ashamed, but still his heart is as cold as the earth he digs in, and so a second vision is conjured. This time a beautiful landscape appears much like one near the old abbey town. It is a pastoral scene of life, light and nature. Gabriel remains callous and so the king goblin gives him a kick. Other goblins follow his lead. More and more scenes evolve of women and men of good cheer regardless of their station in life because they “bore, in their own hearts, an inexhaustible well-spring of affection and devotion.” At last, Gabriel comes to the conclusion that the world is decent and respectable after all. With this realization, the goblins disappear and Gabriel’s self-grown carapace is shed. In the morning Grub is an altered man, and he turned away and wandered “where he might” to seek his bread elsewhere. Ten years later he reappears in the abbey town, tells his story to the clergyman of the church. The story concludes with the moral that: If a man turn sulky and drink by himself at Christmas time, he may make up his mind to be not a bit better for it:

Thoughts

I found the “moral” given at the end of the story to be rather anti-climatic. Yes, perhaps it was meant to reflect on the Dingley Dell Christmas drinking, or meant be humourous and not didactic, but it felt too flat to me after what I thought was a good story. What do you think?

With all the ghosts and goblins floating about in this Christmas story I can’t help but notice the ghost of Christmas stories yet to come. How about you? Find anything in this story that reminds you of other Dickens Christmas tales not mentioned in the commentary.

In this chapter Dickens gives us yet another story. In this case, the story is somewhat different. In “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton” the story is no longer part of a larger chapter but serves as the entire chapter. I wonder how this will effect the chapter’s story, its readers, and the structure of the entire novel, and the expectations of the readers going forward. Will future tales be much longer, will they reflect more closely and comment upon the larger text? The Victorians liked their dose of ghosts and goblins and so this story fits very comfortably into the Christmas celebrations at Dingley Dell and the literary tradition in England.

The tone and setting are perfect for a story. Indeed, the opening is perhaps the best possible one:

“In an old abbey town, down in this part of the country, a long, long while ago - so long that the story must be a true one, because our great grandfathers implicitly believed it - “

We read that in this abbey town is found a sexton and grave-digger named Gabriel Grub. What a great name, one of Dickens’s best. Tristram has pointed out the word aptronym and how Dickens incorporates aptronyms in his work. Gabriel. The angel Gabriel is most often portrayed as being God’s messenger. Grub. What a perfect name for a man who digs graves. Gabriel Grub. With the assigning of this name to the central character of the story we are given both the spiritual and the secular, the immortal and the very essential concept of mortality. The theme of this story will be most interesting as Dickens will, no doubt, braid these two elements together.

Gabriel Grub we are told “was an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow - a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself, and an old wicker bottle ... .” One Christmas Eve he “shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards the old churchyard; for he had got a grave to finish by next morning, and feeling very low, he thought it might raise his spirits, perhaps, if he went on with his work at once.” As he passes through the town he notices the lights of blazing fires and smells the savoury aroma of cooking, but takes no joy in such observations; rather, he takes consolation in thoughts of illness and death. Such thoughts put him in a happy frame of mind. In one instance Grub finds joy in rapping a boy over the head who has been singing.

Thoughts

Did you find the style of beginning this chapter with a story disruptive given the format of earlier stories, or did you find it an effective style? Why?

Why might the telling of a ghost or goblin story have been so enjoyable in the Victorian age?

Gabriel arrives at the churchyard and settles in to dig a grave. At times he sits on a flat tombstone and draws forth his wicker bottle for a drink and enjoys a private joke - “[a] coffin at Christmas! A Christmas Box.” Well, perhaps it’s a good joke when told in context of a graveyard. He follows this up with a hearty “Ho! ho.” But wait! He hears a response of “Ho! ho! ho” from behind him. Lo and behold, “seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once was no being of this world.” It was a goblin who appeared as if he had sat on the same tombstone for hundreds of years. The goblin asks “What man wanders among graves and churchyards on such a night as this? To this question “a wild chorus of voices” screams, in response, “Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!” Gabriel is terrified. The goblin tells Gabriel that the chorus of voices wants him. Why?

The goblin tells Gabriel:

“we know the man with the sulky face and grim scowl, that comes down the street tonight, throwing his evil looks at the children, and grasping his burying spade the tighter. We know the man who struck the boy in the envious malice of his heart, because the boy could be merry, and he could not. We know him, we know him.”

With this the goblin lets out a loud laugh and stands upon his head and does a somersault with extraordinary agility. Then, troops of goblins begin playing leap-frog with the tombstones. The church organ is heard to play louder and louder. Gabriel’s brain whirls, and he finally sinks “through the earth.” A goblin pours a blazing liquid down his throat and Gabriel hears that he will be forced to see “a few of the pictures from our own great storehouse!”

Thoughts

Wow! There is so much going on, so many possible connections, so many speculations we could explore.

Is it me or does the chief goblin remind you a bit of Quilp?

Do you think this goblin, if he does remind you of Quilp, will turn out to be malevolent or benevolent? Why?

At this point in the tale, to what extent do you fear for the final fate of Gabriel?

We encounter a series of instances where there are “mysterious voices” that chant Gabriel’s name. To what extent could these voices be seen as Gabriel’s own conscious slowly emerging from the depths of his being?

At this point we learn that the goblins will show Gabriel, “the man of misery and gloom, a few of the pictures from our own storehouse!” And with this, Gabriel is introduced to the first vision of a poor but proud and happy family who have one of their children near death. The other children of the family crowd around his little bed. The child is discovered dead but his siblings are comforted by the thought that he is now an Angel looking down on his family from heaven. The scene changes and the father and mother of the family are now “old and helpless” but still the parents and the remaining children are content as they crowd around the fireplace “and told and listened to old stories of earlier and bygone days.” In time the parents die, but the few that survive them: “knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it, with their tears ... [but] they knew that they should one day meet again;” Dickens’s Christmas book “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain” evolves the concept of how one’s good memories can keep a person’s world green.

Gabriel seems a bit ashamed, but still his heart is as cold as the earth he digs in, and so a second vision is conjured. This time a beautiful landscape appears much like one near the old abbey town. It is a pastoral scene of life, light and nature. Gabriel remains callous and so the king goblin gives him a kick. Other goblins follow his lead. More and more scenes evolve of women and men of good cheer regardless of their station in life because they “bore, in their own hearts, an inexhaustible well-spring of affection and devotion.” At last, Gabriel comes to the conclusion that the world is decent and respectable after all. With this realization, the goblins disappear and Gabriel’s self-grown carapace is shed. In the morning Grub is an altered man, and he turned away and wandered “where he might” to seek his bread elsewhere. Ten years later he reappears in the abbey town, tells his story to the clergyman of the church. The story concludes with the moral that: If a man turn sulky and drink by himself at Christmas time, he may make up his mind to be not a bit better for it:

Thoughts

I found the “moral” given at the end of the story to be rather anti-climatic. Yes, perhaps it was meant to reflect on the Dingley Dell Christmas drinking, or meant be humourous and not didactic, but it felt too flat to me after what I thought was a good story. What do you think?

With all the ghosts and goblins floating about in this Christmas story I can’t help but notice the ghost of Christmas stories yet to come. How about you? Find anything in this story that reminds you of other Dickens Christmas tales not mentioned in the commentary.

I like the idea that PP offered Dickens the opportunity to prepare his quill for novel writing, foreshadowing ideas that would later become important in his novels. For example, I also noticed the criticism the narrator and the Wellers, father and son, voice with regard to the humanitarian causes allegedly pursued by Mr. Stiggins and his church. In this example, we see that the gifts bestowed on young people in the Tropics are not really useful at all, which shows that rather than studying the "objects" of their philanthropy first, Mr. Stiggins and his followers do good on their own terms, without thinking about what they may achieve by it. Maybe, the only thing they really care about is the feeling of doing good (and doing it on their own terms and with not too much effort)? I immediately thought of Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle in this context, and of the vociferous Honeythunder. Mr. Stiggins's potential for hypocrisy also brought Mr. Chadband to my mind - as he did with regard to his readiness to make the best of his hostess's hospitality.

Like you, Peter, I thought that maybe there would happen something dramatic in the Christmas Eve chapter, something to destroy the joyful and merry atmosphere because after all, whenever the Pickwickians were revelling and enjoying the moment, there was always something unexpected and unwanted crept up. This time, however, they were given the chance to celebrate the wedding and enjoy the ball, and I was glad to see this happen :-)

There are only few writers, with Dickens foremost, who manage to describe scenes of joy and bliss and merriment in a way that is not boring to the reader!

There are only few writers, with Dickens foremost, who manage to describe scenes of joy and bliss and merriment in a way that is not boring to the reader!

Tristram wrote: "Like you, Peter, I thought that maybe there would happen something dramatic in the Christmas Eve chapter, something to destroy the joyful and merry atmosphere because after all, whenever the Pickwi..."

Tristram wrote: "Like you, Peter, I thought that maybe there would happen something dramatic in the Christmas Eve chapter, something to destroy the joyful and merry atmosphere because after all, whenever the Pickwi..."I was glad to see them enjoying the ball as well, and thought Pickwick was at his most charming--dancing with the old lady and making speeches and getting piled on under the mistletoe.

Talking about the mistletoe, it was probably not too surprising to see Mr. Sam Weller make the best of the situation ;-)

As to the story of Gabriel Grub, I could not help thinking that in many respects this tale foreshadows A Christmas Carol because it basically tells the story of a morose outsider's moral reformation on Christmas Eve, and this reformation is not so much brought about by introspection but by supernatural interference. The supernatural element may be due to the Victorians' relish for ghost stories at Christmas but still the story of Gabriel is a shorter version of what happens to Scrooge. Even the incident where Gabriel beats the little boy just because he was singing and having a good time, foreshadows Scrooge, to whom any little sign of mirth and light-heartedness is disgusting in the bitterness of his heart.

As to the moral, I am sure I did not quite get it. It seems to deny Gabriel's change for the better by counterbalancing it with the rheumatism he got (in that night?) Maybe, Dickens wanted to end on an impish note rather than moralize, but all in all, I found the narrator's final remarks rather flat.

As to the moral, I am sure I did not quite get it. It seems to deny Gabriel's change for the better by counterbalancing it with the rheumatism he got (in that night?) Maybe, Dickens wanted to end on an impish note rather than moralize, but all in all, I found the narrator's final remarks rather flat.

Tristram wrote: "There are only few writers, with Dickens foremost, who manage to describe scenes of joy and bliss and merriment in a way that is not boring to the reader! ..."

Tristram wrote: "There are only few writers, with Dickens foremost, who manage to describe scenes of joy and bliss and merriment in a way that is not boring to the reader! ..."I have few memories of passing the time more pleasantly than I did with the Pickwickians celebrating Christmas at Dingley Dell. And most of those other memories of joyous times were also spent in the company of Mr. Dickens' friends. Beign able to write moments like these are God's gift to Dickens, and Dickens' gift to us.

Peter wrote: To what extent did you find this chapter contains elements of the Fezziwig party in ACC?

Actually, I found myself thinking more of the gathering at Fred's house than the Fezziwig party, though both were festive, happy events. I'm not sure if that's from the book, or movie adaptations of ACC that stick in my mind.

Were you waiting for a great crisis, the arrival of Jingle, or any other discordant event to ruin the merriment of the chapter? Why/why not?

Frankly, I was so caught up in the gaiety of the event that it never occurred to me that it might be marred by some catastrophe, and thank God it wasn't! While I'm sure the Inimitable would have made any such interruption of the festivities humorous, it was a lovely respite to have a perfect, unspoiled day.

I have to say that the entire time I spent celebrating the Holiday at Dingley Dell, I kept thinking to myself, "I'll bet Kim just loves this chapter!" In fact, there was a time or two I could have sworn I caught her out of the corner of my eye, adjusting the decorations and choosing the next carol.

Peter wrote: "in time the parents die, but the few that survive them: “knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it, with their tears ... [but] they knew that they should one day meet again;” Dickens’s Christmas book “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain” evolves the concept of how one’s good memories can keep a person’s world green...."

Peter wrote: "in time the parents die, but the few that survive them: “knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it, with their tears ... [but] they knew that they should one day meet again;” Dickens’s Christmas book “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain” evolves the concept of how one’s good memories can keep a person’s world green...."Nice connection, Peter! As much as I didn't care for "The Haunted Man", I will always love the concept of keeping memories green, and this passage is reminiscent (or, more accurately, prescient) of that theme.

I LOVE the name Gabriel Grub, and your analysis of it. The thought of a troupe of goblins chanting the name in the graveyard gave me the chills. I thought Dickens fell short, though, with the story as a whole. Having a bunch of goblins literally beat the Christmas spirit into Gabriel just doesn't seem right, does it? And while his story eventually became known to the vicar and spread though the generations, we never really saw for ourselves how the events that transpired that Christmas Eve changed Gabriel and made him a better, happier man. Dickens tells us, rather than showing us, and it does, as Peter and Tristram remarked, fall flat. Thankfully, he seems to have recognized this flaw by the time he wrote ACC, and it makes all the difference. That, and the fact that in ACC both Scrooge and the reader are well acquainted with the Cratchits, Fred, etc., whereas neither we nor Gabriel know the anonymous family burying their own Tiny Tim in Gabriel's story. It's sad, but not personal, you know?

Tristram wrote: "rather than studying the "objects" of their philanthropy first, Mr. Stiggins and his followers do good on their own terms, without thinking about what they may achieve by it. ..."

Tristram wrote: "rather than studying the "objects" of their philanthropy first, Mr. Stiggins and his followers do good on their own terms, without thinking about what they may achieve by it. ..."One of my pet peeves. As I read this, I think of our church youth group, currently raising money that will take them to Puerto Rico for a few days on a "mission trip", which will be much more a tropical vacation for them than be of any help to actual hurricane victims. Bah, humbug.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "There are only few writers, with Dickens foremost, who manage to describe scenes of joy and bliss and merriment in a way that is not boring to the reader! ..."

I have few memories..."

Mary Lou

Yes. Fred’s Christmas Party certainly is a merry, family affair. Now that I think about it, I think we could add the Cratchit family Christmas as well. While not as merry and lavish, the Cratchit’s do keep the Christmas spirit as best they can, and their family is certainly close.

I have few memories..."

Mary Lou

Yes. Fred’s Christmas Party certainly is a merry, family affair. Now that I think about it, I think we could add the Cratchit family Christmas as well. While not as merry and lavish, the Cratchit’s do keep the Christmas spirit as best they can, and their family is certainly close.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "rather than studying the "objects" of their philanthropy first, Mr. Stiggins and his followers do good on their own terms, without thinking about what they may achieve by it. ..."

..."

I agree with you Mary Lou, you did however remind me of something our group is supposed to be doing for the missions trip our youth group is going on next week. I read the email about it, saved it, and forgot it existed. Needless to say, none of the items have been bought yet. I find it "interesting" that not only do we have cornbread mix, peanut butter, Lipton onion soup mix, and Tylenol, we also have Zinc Picolinate , Starbucks French roast coffee Folger's French vanilla coffee (there must be a difference) and snicker's bars. I find this list rather odd, but if that's what people in Senegal need I guess that's what I'll get, fast. Where I'm going to find something called Zinc Picolinate I haven't a clue.

..."

I agree with you Mary Lou, you did however remind me of something our group is supposed to be doing for the missions trip our youth group is going on next week. I read the email about it, saved it, and forgot it existed. Needless to say, none of the items have been bought yet. I find it "interesting" that not only do we have cornbread mix, peanut butter, Lipton onion soup mix, and Tylenol, we also have Zinc Picolinate , Starbucks French roast coffee Folger's French vanilla coffee (there must be a difference) and snicker's bars. I find this list rather odd, but if that's what people in Senegal need I guess that's what I'll get, fast. Where I'm going to find something called Zinc Picolinate I haven't a clue.

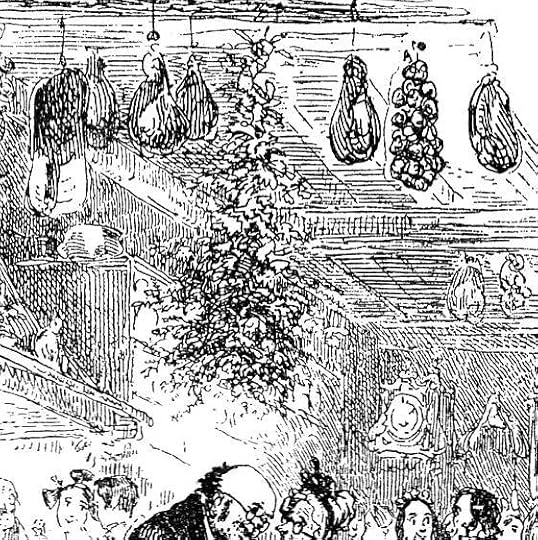

Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's

Chapter 28

Phiz - 1836

Commentary:

Armed with a substantial cod fish and several barrels of oysters, the Pickwickians now descend upon Manor Farm, Dingley Dell, for a full round of traditional Christmas festivities and the wedding of one of Wardle's daughters, Isabella, to Mr. Trundle. The following illustration involves Mr. Pickwick's gallantry to Mr. Wardle's elderly and somewhat deaf mother at one of the many dances held at Dingley Dell.

As Mr. Weller concluded this moral tale, with which the fat boy appeared much affected, they all three repaired to the large kitchen, in which the family were by this time assembled, according to annual custom on Christmas Eve, observed by old Wardle's forefathers from time immemorial.

From the centre of the ceiling of this kitchen, old Wardle had just suspended, with his own hands, a huge branch of mistletoe, and this same branch of mistletoe instantaneously gave rise to a scene of general and most delightful struggling and confusion; in the midst of which, Mr. Pickwick, with a gallantry that would have done honour to a descendant of Lady Tollimglower herself, took the old lady by the hand, led her beneath the mystic branch, and saluted her in all courtesy and decorum. The old lady submitted to this piece of practical politeness with all the dignity which befitted so important and serious a solemnity, but the younger ladies, not being so thoroughly imbued with a superstitious veneration for the custom, or imagining that the value of a salute is very much enhanced if it cost a little trouble to obtain it, screamed and struggled, and ran into corners, and threatened and remonstrated, and did everything but leave the room, until some of the less adventurous gentlemen were on the point of desisting, when they all at once found it useless to resist any longer, and submitted to be kissed with a good grace.

Once again we get to notice the details. I don't know how they decide on what details they want, but here they are:

The first, Mr. Pickwick and the old lady

Seasonal decorations and mistletoe

The grand fireplace

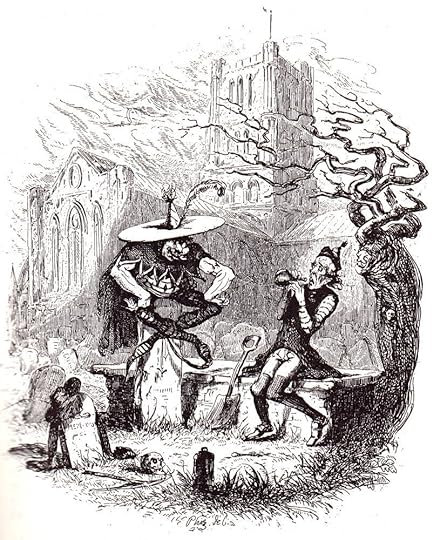

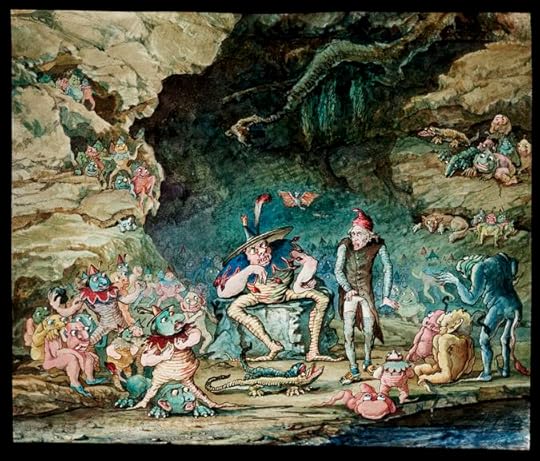

The Goblin and the Sexton

Chapter 29

Phiz - 1836

Commentary:

The passage from "The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton" illustrated is this:

Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange, unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once, was no being of this world. His long, fantastic legs which might have reached the ground, were cocked up, and crossed after a quaint, fantastic fashion; his sinewy arms were bare; and his hands rested on his knees. On his short, round body, he wore a close covering, ornamented with small slashes; a short cloak dangled at his back; the collar was cut into curious peaks, which served the goblin in lieu of ruff or neckerchief; and his shoes curled up at his toes into long points. On his head, he wore a broad-brimmed sugar-loaf hat, garnished with a single feather. The hat was covered with the white frost; and the goblin looked as if he had sat on the same tombstone very comfortably, for two or three hundred years. He was sitting perfectly still; his tongue was put out, as if in derision; and he was grinning at Gabriel Grub with such a grin as only a goblin could call up. [chapter 29]

"The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton," Dickens's version of Washington Irving's humorous tale of the supernatural "Rip Van Winkle," from The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon (1819), is not merely an enjoyable little Christmas ghost story, but a premonitory treatment of the theme of spiritual and social renewal for a misanthrope found in A Christmas Carol (1843) and The Chimes (1844), which together established the nineteenth-century British vogue for Christmas Books. Unlike those fuller treatments of the theme, however, this inset narrative is told in the voice of one of the novel's characters, Mr. Wardle, rather than that of a detached omniscient.

The Phiz illustration acts as the perfect complement to the dramatic tale, blending a gothic setting — note the gnarled, leafless tree whose arms seem to reach out for the quivering sexton — and a caricature of a goblin in a gigantic hat. Phiz realizes the leering goblin most effectively through his posture and wrestler's forearms, contrasting his contortionist's posture with the rigid, terrified human being in the churchyard.

‘Governor in?’ inquired Sam, in reply to the question.

Chapter 27

Thomas Nast - 1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Governor in?’ inquired Sam, in reply to the question.

‘No, he isn’t,’ replied Mrs. Weller; for the rather stout lady was no other than the quondam relict and sole executrix of the dead-and-gone Mr. Clarke; ‘no, he isn’t, and I don’t expect him, either.’

‘I suppose he’s drivin’ up to-day?’ said Sam.

‘He may be, or he may not,’ replied Mrs. Weller, buttering the round of toast which the red-nosed man had just finished. ‘I don’t know, and, what’s more, I don’t care.—Ask a blessin’, Mr. Stiggins.’

The red-nosed man did as he was desired, and instantly commenced on the toast with fierce voracity.

The appearance of the red-nosed man had induced Sam, at first sight, to more than half suspect that he was the deputy-shepherd of whom his estimable parent had spoken. The moment he saw him eat, all doubt on the subject was removed, and he perceived at once that if he purposed to take up his temporary quarters where he was, he must make his footing good without delay. He therefore commenced proceedings by putting his arm over the half-door of the bar, coolly unbolting it, and leisurely walking in.

‘Mother-in-law,’ said Sam, ‘how are you?’

‘Why, I do believe he is a Weller!’ said Mrs. W., raising her eyes to Sam’s face, with no very gratified expression of countenance.

‘I rayther think he is,’ said the imperturbable Sam; ‘and I hope this here reverend gen’l’m’n ‘ll excuse me saying that I wish I was the Weller as owns you, mother-in-law.’

This was a double-barrelled compliment. It implied that Mrs. Weller was a most agreeable female, and also that Mr. Stiggins had a clerical appearance. It made a visible impression at once; and Sam followed up his advantage by kissing his mother-in-law.

‘Get along with you!’ said Mrs. Weller, pushing him away.

‘For shame, young man!’ said the gentleman with the red nose.

‘No offence, sir, no offence,’ replied Sam; ‘you’re wery right, though; it ain’t the right sort o’ thing, ven mothers-in-law is young and good-looking, is it, Sir?’

‘It’s all vanity,’ said Mr. Stiggins.

‘Ah, so it is,’ said Mrs. Weller, setting her cap to rights.

Sam thought it was, too, but he held his peace.

Preparations for Supper — A plate of hot buttered toast. —

Chapter 27

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Text Illustrated

Sam looked round in the direction whence the voice proceeded. It came from a rather stout lady of comfortable appearance, who was seated beside the fireplace in the bar, blowing the fire to make the kettle boil for tea. She was not alone; for on the other side of the fireplace, sitting bolt upright in a high-backed chair, was a man in threadbare black clothes, with a back almost as long and stiff as that of the chair itself, who caught Sam's most particular and especial attention at once.

He was a prim-faced, red-nosed man, with a long, thin countenance, and a semi-rattlesnake sort of eye — rather sharp, but decidedly bad. He wore very short trousers, and black cotton stockings, which, like the rest of his apparel, were particularly rusty. His looks were starched, but his white neckerchief was not, and its long limp ends straggled over his closely-buttoned waistcoat in a very uncouth and unpicturesque fashion. A pair of old, worn, beaver gloves, a broad-brimmed hat, and a faded green umbrella, with plenty of whalebone sticking through the bottom, as if to counterbalance the want of a handle at the top, lay on a chair beside him; and, being disposed in a very tidy and careful manner, seemed to imply that the red-nosed man, whoever he was, had no intention of going away in a hurry.

To do the red-nosed man justice, he would have been very far from wise if he had entertained any such intention; for, to judge from all appearances, he must have been possessed of a most desirable circle of acquaintance, if he could have reasonably expected to be more comfortable anywhere else. The fire was blazing brightly under the influence of the bellows, and the kettle was singing gaily under the influence of both. A small tray of tea-things was arranged on the table; a plate of hot buttered toast was gently simmering before the fire; and the red-nosed man himself was busily engaged in converting a large slice of bread into the same agreeable edible, through the instrumentality of a long brass toasting-fork. Beside him stood a glass of reeking hot pine-apple rum-and-water, with a slice of lemon in it; and every time the red-nosed man stopped to bring the round of toast to his eye, with the view of ascertaining how it got on, he imbibed a drop or two of the hot pine-apple rum-and-water, and smiled upon the rather stout lady, as she blew the fire.

Commentary

The picaresque form which he had inherited from Fielding and Smollett allowed Dickens opportunities to introduce a great range of characters and themes, including his delightful exposure of hypocrisy in the figure of the nonconformist minister Mr. Stiggins and of gullibility in Stiggins's addle-headed but devoted parishioner Mrs. Weller, Sam's "mother-in-law," that is, his stepmother.

Neither the British Household Edition illustrator of the seventies, Phiz, nor Phiz in the original 1836 sequence realizes this scene in The Marquis of Granby at Dorking. However, Thomas Nast in "Governor in?" Inquired Sam (1873) offers an extreme caricature of the red-nosed Shepherd of the Brick Lane congregation in the parlor with Mrs. Weller. Nast has abandoned all subtlety of characterization in the cartoon, but establishes the setting effectively and does justice Dickens's satire of the hypocritical nonconformist minister whose excessive eating and drinking represent his infantile egocentricity. In contrast, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, one of the leading book illustrators of mid-nineteenth-century America, adopts a realistic approach, even to the red-nosed man, focusing on the preparation of the toast prior to consuming it voraciously before the parlor fire, ministered to by a comely, middle-aged publican, "a rather stout lady of comfortable appearance".

The scene is the parlor at The Marquis of Granby, the public house and coaching inn that Mrs. Weller runs at Dorking, outside London, which Dickens introduces into the novel in chapter 27 as part of Sam's "back-story." While preaching temperance to his Brick Lane congregants, Stiggins is a dipsomaniac addicted to Mrs. Weller's pineapple rum — his reiterated "red nose" being the outward and visible sign of his alcoholism and hypocrisy. Dickens and Darley find his drinking amusing, but his hypocrisy about it and fleecing the flock reprehensible. However, Darley adopts an almost photographic realism in depicting the scene, paying strict attention to the detailing of the tankards, the tile-lined fireplace, the chair, tea-table, bellows, and toasting fork, and Stiggins's physical signifiers, the hat, gloves, and umbrella on the chair. Without recourse to comic distortion Darley conveys accurately Dickens's physical description of Stiggins's "long thin countenance."

The Rev. Mr. Stiggins and Mrs. Weller

Chapter 27

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867 - Diamond Edition

Commentary:

In this full-page illustration, Eytinge has realized a moment that sheds some light on Sam Weller's background and introduces the reader to the gullible Mrs. Weller and the hypocritical "dissenting" on non-conformist clergyman Stiggins.

Sam Weller has taken a temporary leave of absence of two days (prior to the departure of the Pickwickians for Christmas at Dingley Dell) to visit his father, Tony, at The Marquis of Granby, a well-known Dorking public house and coaching inn ("a roadside public-house of the better class"). When he arrives, he finds his "mother-in-law" (that is, his stepmother) entertaining the local dissenting or nonconformist minister, the Reverend Mr. Stiggins, for whom both Sam Weller and Charles Dickens share a low regard:

"Now, then!" said a shrill female voice the instant Sam thrust his head in at the door, "what do you want, young man?"

Sam looked round in the direction whence the voice proceeded. It came from a rather stout lady of comfortable appearance, who was seated beside the fireplace in the bar, blowing the fire to make the kettle boil for tea. She was not alone; for on the other side of the fireplace, sitting bolt upright in a high-backed chair, was a man in threadbare black clothes, with a back almost as long and stiff as that of the chair itself, who caught Sam's most particular and especial attention at once.

He was a prim-faced, red-nosed man, with a long, thin countenance, and a semi-rattlesnake sort of eye, —rather sharp, but decidedly bad. He wore very short trousers, and black cotton stockings, which, like the rest of his apparel, were particularly rusty. His looks were starched, but his white neckerchief was not, and its long limp ends straggled over his closely-buttoned waistcoat in a very uncouth and unpicturesque fashion. A pair of old, worn, beaver gloves, a broad-brimmed hat, and a faded green umbrella, with plenty of whalebone sticking through the bottom, as if to counterbalance the want of a handle at the top, lay on a chair beside him; and, being disposed in a very tidy and careful manner, seemed to imply that the red-nosed man, whoever he was, had no intention of going away in a hurry.

To do the red-nosed man justice, he would have been very far from wise if he had entertained any such intention; for, to judge from all appearances, he must have been possessed of a most desirable circle of acquaintance, if he could have reasonably expected to be more comfortable anywhere else. The fire was blazing brightly under the influence of the bellows, and the kettle was singing gaily under the influence of both. A small tray of tea-things was arranged on the table; a plate of hot buttered toast was gently simmering before the fire; and the red-nosed man himself was busily engaged in converting a large slice of bread into the same agreeable edible, through the instrumentality of a long brass toasting-fork. Beside him stood a glass of reeking hot pine-apple rum-and-water, with a slice of lemon in it; and every time the red-nosed man stopped to bring the round of toast to his eye, with the view of ascertaining how it got on, he imbibed a drop or two of the hot pine-apple rum-and-water, and smiled upon the rather stout lady, as she blew the fire.

An unusual aspect of the illustration in Eytinge's sequence is the presence of considerable background detail, including the buttered toast, the tea-pot, the hob, and Stiggins's umbrella and hat. In the longer programs of illustration — those by Seymour and Browne (1836-37), Browne in the British Household Edition (1873), and Nast in the American Household Edition, the equivalent scene in each case involves a less subtle satirisation of the hypocrite and "bad shepherd". The figure of Stiggins that we see in Phiz's "sketch is consistent with that of the later illustrators and editions, Stiggins's most prominent characteristics being his skeletal thinness and his large, red nose, which immediately proclaims him an alcoholic and therefore a hypocrite. Complementing Stiggins's initial appearance in the text, Eytinge shows the dissenting preacher and "deputy shepherd" of Dorking's Emmanuel Chapel leisurely consuming his trademark beverage — a tumbler of hot water, three lumps of sugar, and pineapple rum — in Susan Weller's parlor at The Marquis of Granby. As opposed to the somewhat theatrical perspectives of Phiz and Nast, Eytinge shows the reader what Sam actually sees as his pokes his head into the room, and avoids the excesses of caricature and cartoon employed by the other illustrators. The 1867 illustration relies for the effectiveness of the twin characterizations on the clergyman's red nose and complacent expression, and on Mrs. Weller's self-satisfaction, to which the sketched in parlor setting is a suitable adjunct.

Sam looked at the Fat Boy with great astonishment

Chapter 28

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Since this is the first meeting of two of the novel's chief comic characters — Pickwick's street-wise Cockney servant, Sam Weller, and Wardle's narcoleptic page, Joe "The Fat Boy" — this should be significant among the twenty-seven wholly new illustrations that Phiz created in 1873 for the fifty-seven woodcuts in the Household Edition of The Pickwick Papers, issued in 1874 (perhaps because Chapman and Hall realised that, despite Phiz's name recognition with the public, his work would have little drawing power because it was often just a bad imitation of the new Sixties style). The plate, whatever its shortcoming as a composition, reminds the reader that Sam Weller was still in Pickwick's future when the Pickwickians last visited Dingley Dell. Pickwick has left Sam and Joe to pack the luggage (as well as casks of oysters, one such cask being just behind the trunk between Sam and Joe, and a large cod-fish that has accompanied the Pickwickians on the stage-coach from London) onto the cart while he, Tupman, Snodgrass, and Winkle make their way by foot from Muggleton to Dingley Dell.

In the background is the sign of the Blue Lion, Muggleton, reminding the reader of the Muggleton/Dingley Dell cricket match that concluded with rather too much drinking, although Pickwick put the ill-effects of the banquet down to too much salmon. Unfortunately, this twenty-seventh illustration lacks the humour and charm of the accompanying text, with the East London and Kentish dialects of the two servants helping to distinguish them.

"Sam looked at the Fat Boy with great astonishment, but without saying a word." gives the reader the precise moment, but the reader must absorb the entire textual scene to understand the picture's implications, which, as usual, involve Sam's doing everything and Joe's doing nothing but observe. It begins with Pickwick's ordering Sam to assist Joe (not do all the packing himself). Pickwick has elected not to ride since there would be insufficient room for his friends; his determination to walk reminds the reader of the difficulties the Pickwickians encountered with the rented horse and carriage earlier, when travelling from Rochester to Dingley Dell, and realised in "The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing with the chaise whip in his hand, &c.". Presumably the presence of Joe, "The Fat Boy" (last seen in "Mr. Tupman looked round. There was the fat boy" ) and the horse and cart would instantly have recalled Pickwick's previous transportation problems and motivate his intention to walk to Dingley Dell:

"Help Mr. Wardle’s servant to put the packages into the cart, and then ride on with him. We will walk forward at once."

Having given this direction, and settled with the coachman, Mr. Pickwick and his three friends struck into the footpath across the fields, and walked briskly away, leaving Mr. Weller and the fat boy confronted together for the first time. Sam looked at the fat boy with great astonishment, but without saying a word; and began to stow the luggage rapidly away in the cart, while the fat boy stood quietly by, and seemed to think it a very interesting sort of thing to see Mr. Weller working by himself.

"There," said Sam, throwing in the last carpet-bag, "there they are!"

"Yes," said the fat boy, in a very satisfied tone, "there they are."

"Vell, young twenty stun," said Sam, "you're a nice specimen of a prize boy, you are!’ ‘Thank’ee,’ said the fat boy.

"You ain’t got nothin’ on your mind as makes you fret yourself, have you?" inquired Sam.

"Not as I knows on," replied the fat boy.

"I should rayther ha’ thought, to look at you, that you was a-labourin’ under an unrequited attachment to some young ‘ooman," said Sam.

The fat boy shook his head.

"Vell," said Sam, "I am glad to hear it. Do you ever drink anythin’?"

"I likes eating better," replied the boy.

"Ah,’ said Sam, ‘I should ha’ s’posed that; but what I mean is, should you like a drop of anythin’ as’d warm you? but I s’pose you never was cold, with all them elastic fixtures, was you?"

"Sometimes," replied the boy; "and I likes a drop of something, when it’s good."

"Oh, you do, do you?" said Sam, "come this way, then!"

The Blue Lion tap was soon gained, and the fat boy swallowed a glass of liquor without so much as winking — a feat which considerably advanced him in Mr. Weller’s good opinion. Mr. Weller having transacted a similar piece of business on his own account, they got into the cart.

Before Mr. Pickwick distinctly knew what was the matter, he was surrounded by the whole body, and kissed by every one of them

Chapter 28

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Chapter 28

Thomas Nast - 1874 American Household Edition

Commentary:

As charming a figure as Thomas Nast's "Mr. Pickwick" cuts by himself under the mistletoe at Dingley Dell in the American Household Edition, Pickwick's being surrounded by a bevy of young beauties, in particular, Mr. Wardle's adolescent nieces, and the festive context generally are much appealing, despite a certain woodenness of expression that should suggest something of Pickwick's delight in "Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's", in which the protagonist is gallantly offering Mr. Wardle's aged mother an opportunity to dance, and thereby recapture (if only momentarily) a sense of her lost youth as she joins young and middle-aged revelers in seasonal festivity. In the 1873 Christmas Eve plate, Phiz shifts his attention to the scene in which the younger women of the house surround a middle-aged and bashful Pickwick under the mistletoe, precisely the subject which Nast addresses. In contrast to the sprightliness of Phiz's figures in both 1837 and 1837 illustrations, there is an unfortunate woodenness about the seven figures in the Nast mistletoe scene, "It was a pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick in the center of the group", and Nast's Wardle nieces are not nearly so attractive as Phiz's, nor is there in Nast's composition much informing background detail, although he shows Old Wardle (right), looking on with approval. Again, Pickwick seems paralyzed rather than energized by the delightful situation.

Blindman's Bluff

Chapter 28

William Heath

1837

Text Illustrated:

It was a pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick in the centre of the group, now pulled this way, and then that, and first kissed on the chin, and then on the nose, and then on the spectacles, and to hear the peals of laughter which were raised on every side; but it was a still more pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick, blinded shortly afterwards with a silk handkerchief, falling up against the wall, and scrambling into corners, and going through all the mysteries of blind-man’s buff, with the utmost relish for the game, until at last he caught one of the poor relations, and then had to evade the blind-man himself, which he did with a nimbleness and agility that elicited the admiration and applause of all beholders. The poor relations caught the people who they thought would like it, and, when the game flagged, got caught themselves. When they all tired of blind-man’s buff, there was a great game at snap-dragon, and when fingers enough were burned with that, and all the raisins were gone, they sat down by the huge fire of blazing logs to a substantial supper, and a mighty bowl of wassail, something smaller than an ordinary wash-house copper, in which the hot apples were hissing and bubbling with a rich look, and a jolly sound, that were perfectly irresistible.

The Goblin and the Sexton

Chapter 29

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold.

Chapter 29

Thomas Nast

Commentary:

In the number immediately following Christmas 1836, Dickens and his illustrator provide two outstanding visual accompaniments to the text, one ("Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's") focusing on the titular character's celebration of Old Christmas under the mistletoe, the other whimsically realizing the interpolated Christmas ghost story of Gabriel Grub, a proto-Scrooge figure, in "The Goblin and The Sexton". Both subjects very much appealed to the Household Edition's illustrators, although Nast's treatment of "The Goblin and The Sexton" lacks both the humor and the telling detail of Phiz's pair of much more lively renditions. In particular, in Phiz's embedded references to "memory" on a pair of tombstones in the 1873 illustration (down left, and up right), Phiz is connecting the moral life with remembering the collective past of the village or community, an awareness that the misanthropic Gabriel Grub has replaced with self-centeredness and giving himself up to mindless drinking. He is, exactly like Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol (1843) "an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow — a morose and lonely man who consorted with nobody but himself", so that the supernatural visitation serves as a catalyst to force him to remember his common humanity with those whom he inters. Phiz better realizes evocatively the twilight hour and lonely setting in his original illustration, his second iteration being rather "overpopulated" by goblins, so to speak.

"The Goblin and The Sexton" in the original series (for the January 1837 monthly number) remains a fascinating blend of the weird and macabre on the one hand, and of the comic and whimsical on the other. The tomb and gnarled tree are brilliant devices for setting the mood, so that one wonders why Phiz elected to replace the eerie tree as another person in the scene (right) with a perfectly conventional oak (left) in the 1873 illustration, which, in providing a closeup of the Goblin and the sexton has eliminated the noble English Gothic church, with its square tower reaching heavenward and its elegant stained-glass window in the transept. The scene in the text has so much pictorial potential that Phiz could not resist revisiting the January 1837 illustration; likewise, the American Household Edition illustrator must have felt compelled to try his hand at the same scene, despite his lack of familiarity with such a setting as an English country churchyard. Thomas Nast's Goblin King in "His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold" is hardly credible (almost pinata-like in his rotundity and artificial expression), and Nast's catatonic Gabriel Grub (surprisingly impressionistic for a period that valued realism in illustration) is hardly the figure of fun that Phiz's sexton constitutes in "Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure". Given the opportunity to rethink his original composition without Dickens's supervision, Phiz seems to be enjoying the whole situation, depicting eight miniature versions of the Goblin chief, who serve as an appreciative audience for Grub's discomfort. Phiz's Gothic church backdrop and tomb, ably engraved by the Dalziels, suggest greater verisimilitude than Nast's cemetery and square-towered country church. However, neither Household Edition illustration is as effective in its depiction of the two figures as Phiz's 1837 original.

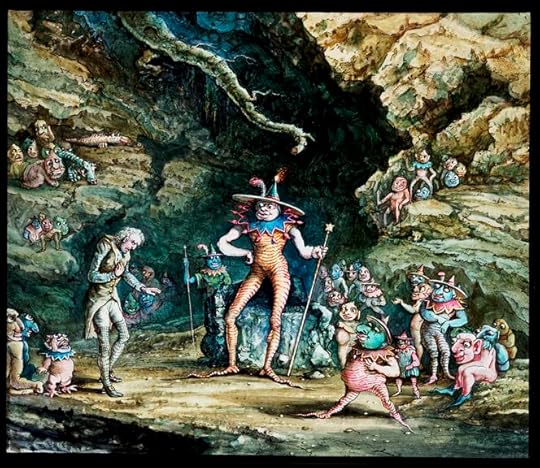

And now, ' said the Goblin King, 'Show the man of misery and gloom a few of the pictures from our own storehouse'

Chapter 29

T. Onwhyn and Sam Weller

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘At last the game reached to a most exciting pitch; the organ played quicker and quicker, and the goblins leaped faster and faster, coiling themselves up, rolling head over heels upon the ground, and bounding over the tombstones like footballs. The sexton’s brain whirled round with the rapidity of the motion he beheld, and his legs reeled beneath him, as the spirits flew before his eyes; when the goblin king, suddenly darting towards him, laid his hand upon his collar, and sank with him through the earth.

‘When Gabriel Grub had had time to fetch his breath, which the rapidity of his descent had for the moment taken away, he found himself in what appeared to be a large cavern, surrounded on all sides by crowds of goblins, ugly and grim; in the centre of the room, on an elevated seat, was stationed his friend of the churchyard; and close behind him stood Gabriel Grub himself, without power of motion.

‘“Cold to-night,” said the king of the goblins, “very cold. A glass of something warm here!”

‘At this command, half a dozen officious goblins, with a perpetual smile upon their faces, whom Gabriel Grub imagined to be courtiers, on that account, hastily disappeared, and presently returned with a goblet of liquid fire, which they presented to the king.

‘“Ah!” cried the goblin, whose cheeks and throat were transparent, as he tossed down the flame, “this warms one, indeed! Bring a bumper of the same, for Mr. Grub.”

‘It was in vain for the unfortunate sexton to protest that he was not in the habit of taking anything warm at night; one of the goblins held him while another poured the blazing liquid down his throat; the whole assembly screeched with laughter, as he coughed and choked, and wiped away the tears which gushed plentifully from his eyes, after swallowing the burning draught.

‘“And now,” said the king, fantastically poking the taper corner of his sugar-loaf hat into the sexton’s eye, and thereby occasioning him the most exquisite pain; “and now, show the man of misery and gloom, a few of the pictures from our own great storehouse!”

Kim wrote: "Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's

Chapter 28

Phiz - 1836

Commentary:

Armed with a substantial cod fish and several barrels of oysters, the Pickwickians now descend upon Manor Farm, Dingley Dell, fo..."

Thank you, Kim.

This illustration by Hablot Browne, Chapter 28, 1836 clearly shows the joy, happiness and celebratory nature of the entire room. What I suggest is that this illustration is very similar to the much more famous John Leech illustration in A Christmas Carol that appeared some 10 years later.

First, In each we have a very similar general structure. Both present two figures in the centre of the frame. In both cases the male is portly and the female thinner. In both illustrations we have a very clear indication that there is a mingling of ages. Both youth and mature adults are seen interconnecting and celebrating. In both illustrations there is a large bunch of mistletoe that hangs in the centre above our dancing couple.

I believe that other aspects Browne’s illustration were incorporated in the Leech illustration as well. John Leech was a prolific and creative illustrator. I do find, however, that his much more famous Christmas celebration illustration descends from Browne’s earlier depiction.

Chapter 28

Phiz - 1836

Commentary:

Armed with a substantial cod fish and several barrels of oysters, the Pickwickians now descend upon Manor Farm, Dingley Dell, fo..."

Thank you, Kim.

This illustration by Hablot Browne, Chapter 28, 1836 clearly shows the joy, happiness and celebratory nature of the entire room. What I suggest is that this illustration is very similar to the much more famous John Leech illustration in A Christmas Carol that appeared some 10 years later.

First, In each we have a very similar general structure. Both present two figures in the centre of the frame. In both cases the male is portly and the female thinner. In both illustrations we have a very clear indication that there is a mingling of ages. Both youth and mature adults are seen interconnecting and celebrating. In both illustrations there is a large bunch of mistletoe that hangs in the centre above our dancing couple.

I believe that other aspects Browne’s illustration were incorporated in the Leech illustration as well. John Leech was a prolific and creative illustrator. I do find, however, that his much more famous Christmas celebration illustration descends from Browne’s earlier depiction.

Kim wrote: "Preparations for Supper — A plate of hot buttered toast. —

Chapter 27

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Text Illustrated

Sam looked round in the direction whence the voice proceeded. It came from a rat..."

I like Darley’s work very much. This illustration is very detailed and faithful to the text. It does, however, in its exactness have a slight frosty nature to it that even the fireplace cannot remove.

Chapter 27

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Text Illustrated

Sam looked round in the direction whence the voice proceeded. It came from a rat..."

I like Darley’s work very much. This illustration is very detailed and faithful to the text. It does, however, in its exactness have a slight frosty nature to it that even the fireplace cannot remove.

A Grave in the Churchyard.

Chapter 29

Joseph Grego

Text Illustrated;

‘A little before twilight, one Christmas Eve, Gabriel shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards the old churchyard; for he had got a grave to finish by next morning, and, feeling very low, he thought it might raise his spirits, perhaps, if he went on with his work at once. As he went his way, up the ancient street, he saw the cheerful light of the blazing fires gleam through the old casements, and heard the loud laugh and the cheerful shouts of those who were assembled around them; he marked the bustling preparations for next day’s cheer, and smelled the numerous savoury odours consequent thereupon, as they steamed up from the kitchen windows in clouds. All this was gall and wormwood to the heart of Gabriel Grub; and when groups of children bounded out of the houses, tripped across the road, and were met, before they could knock at the opposite door, by half a dozen curly-headed little rascals who crowded round them as they flocked upstairs to spend the evening in their Christmas games, Gabriel smiled grimly, and clutched the handle of his spade with a firmer grasp, as he thought of measles, scarlet fever, thrush, whooping-cough, and a good many other sources of consolation besides.

‘In this happy frame of mind, Gabriel strode along, returning a short, sullen growl to the good-humoured greetings of such of his neighbours as now and then passed him, until he turned into the dark lane which led to the churchyard. Now, Gabriel had been looking forward to reaching the dark lane, because it was, generally speaking, a nice, gloomy, mournful place, into which the townspeople did not much care to go, except in broad daylight, and when the sun was shining; consequently, he was not a little indignant to hear a young urchin roaring out some jolly song about a merry Christmas, in this very sanctuary which had been called Coffin Lane ever since the days of the old abbey, and the time of the shaven-headed monks. As Gabriel walked on, and the voice drew nearer, he found it proceeded from a small boy, who was hurrying along, to join one of the little parties in the old street, and who, partly to keep himself company, and partly to prepare himself for the occasion, was shouting out the song at the highest pitch of his lungs. So Gabriel waited until the boy came up, and then dodged him into a corner, and rapped him over the head with his lantern five or six times, just to teach him to modulate his voice. And as the boy hurried away with his hand to his head, singing quite a different sort of tune, Gabriel Grub chuckled very heartily to himself, and entered the churchyard, locking the gate behind him.

The Story of the Goblins who Stole a Sexton

Chapter 29

Joseph Grego

1899

Text Illustrated:

‘“I am afraid my friends want you, Gabriel,” said the goblin, thrusting his tongue farther into his cheek than ever—and a most astonishing tongue it was—“I’m afraid my friends want you, Gabriel,” said the goblin.

‘“Under favour, Sir,” replied the horror-stricken sexton, “I don’t think they can, Sir; they don’t know me, Sir; I don’t think the gentlemen have ever seen me, Sir.”

‘“Oh, yes, they have,” replied the goblin; “we know the man with the sulky face and grim scowl, that came down the street to-night, throwing his evil looks at the children, and grasping his burying-spade the tighter. We know the man who struck the boy in the envious malice of his heart, because the boy could be merry, and he could not. We know him, we know him.”

‘Here, the goblin gave a loud, shrill laugh, which the echoes returned twentyfold; and throwing his legs up in the air, stood upon his head, or rather upon the very point of his sugar-loaf hat, on the narrow edge of the tombstone, whence he threw a Somerset with extraordinary agility, right to the sexton’s feet, at which he planted himself in the attitude in which tailors generally sit upon the shop-board.

‘“I—I—am afraid I must leave you, Sir,” said the sexton, making an effort to move.

‘“Leave us!” said the goblin, “Gabriel Grub going to leave us. Ho! ho! ho!”

‘As the goblin laughed, the sexton observed, for one instant, a brilliant illumination within the windows of the church, as if the whole building were lighted up; it disappeared, the organ pealed forth a lively air, and whole troops of goblins, the very counterpart of the first one, poured into the churchyard, and began playing at leap-frog with the tombstones, never stopping for an instant to take breath, but “overing” the highest among them, one after the other, with the most marvellous dexterity. The first goblin was a most astonishing leaper, and none of the others could come near him; even in the extremity of his terror the sexton could not help observing, that while his friends were content to leap over the common-sized gravestones, the first one took the family vaults, iron railings and all, with as much ease as if they had been so many street-posts.

‘At last the game reached to a most exciting pitch; the organ played quicker and quicker, and the goblins leaped faster and faster, coiling themselves up, rolling head over heels upon the ground, and bounding over the tombstones like footballs. The sexton’s brain whirled round with the rapidity of the motion he beheld, and his legs reeled beneath him, as the spirits flew before his eyes; when the goblin king, suddenly darting towards him, laid his hand upon his collar, and sank with him through the earth.

A hand-painted, large format magic lantern slide, painted by W R Hill and shown at the Royal Polytechnic Institution, London over Christmas 1875.

This slide is from 'Gabriel Grub and the Grim Goblin', a popular tale shown at the Royal Polytechnic Institution over Christmas 1875 based on 'The Story of The Goblin Who Stole A Sexton' by Charles Dickens which appeared in 'The Pickwick Papers'.

The Royal Polytechnic Institution in Regent Street, London, was renowned for its spectacular magic lantern shows employing as many as six huge lanterns projecting large, hand-painted slides eight inches (20.3 cm) by five inches (12.7 cm).

Kim wrote: "A Grave in the Churchyard.

Chapter 29

Joseph Grego

Text Illustrated;

‘A little before twilight, one Christmas Eve, Gabriel shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards ..."

The more I think about it the more Grub has many of the same qualities that we will visit again in Scrooge.