The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 24-26

Chapter 25 is rather long, as can already guessed from the introductory title, and in it, the narrator brings the Ipswich episode to a close by showing us how Mr. Pickwick and his friends extricate themselves from the unfortunate situation of standing accused before they Mayor as mischief-makers breaking the public order and how they can once more thwart the plans of Mr. Jingle and his “servant” Job.

Here’s WHAT HAPPENS

As soon as Sam Weller notices that they are going to take him and the Pickwickians to the house with the green garden gate that he has seen Job Trotter emerge from, his wrath gives way to curiosity as he realizes that this is a great opportunity to see what is inside that house. Immediately, his curiosity is rewarded as one of the first sights he takes in is “a very smart and pretty-faced servant-girl”, who opens the gate and who – as we learn later – is called Mary. The narrator here aptly gives an impression of human curiosity as such by describing the Victorian predecessors of smartphone gloaters as:

Once inside, our friends are taken into the presence of His Worship, the Mayor, who tries his hand at questioning Mr. Pickwick and his friends. However, Mr. Nupkins is very clumsy about it and often betrays a gross degree of ignorance with regard to proper proceedings that his secretary Mr. Jinks tries his best to set him right without seeming to be doing so. Matters are not made easier for the official because Mr. Weller is anything but cowed by the constable Grummer or by the Mayor himself. In a way, this scene reminded me of two things extremely unlike each other, namely of the character of Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, e.g. as presented here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82dYx...

but also, especially in the scene where the policemen try not to laugh about Sam Weller’ funny comments so as not to incur the wrath of Mr. Nupkins, this reminded me of “The Life of Brian”, where the guards try not to laugh at the rather bawdy names of Pilates’s friends. I wonder if the Monty Python people have ever read that scene from Pickwick Papers:

It’s once again Mr. Weller who saves the day by telling Mr. Pickwick what he knows about Job Trotter’s frequenting the house of the Mayor, and in a private conference with that worthy, which is reluctantly granted, Mr. Nupkins is informed that Captain Fitz-Marshall, the acquaintance Mr. Nupkins and his wife have vaunted in the faces of all their friends, especially the – and here comes another brilliant name I don’t want to suppress – the Porkenhams, is maybe not the man he seems but a base swindler and adventurer. Apparently, this is a very embarrassing bit of news to Mr. Nupkins because they have been so impressed with Fitz-Marshall that his advances towards Miss Nupkins’s hand, in a matrimonial light, have not been looked down upon as unwelcome. Mr. Nupkins therefore demands proof from Mr. Pickwick, and this gentleman suggests, self-confidently, that he should be allowed to face Jingle-Fitz-Marshall, and then everyone could see what would happen. Mr. Nupkins agrees and forbears from any further prosecution of the Pickwickians. He then breaks the news to his wife and his daughter, who are described in these not very encouraging sentences:

Again, we see that in Pickwick Papers men of public station, and very overbearing men at that, are often henpecked at home. Do you think this is a pattern whose originality and ability to amuse quickly fizzles out? Or do you see any differences between Mr. Nupkins, Mr. Pott and Mr. Leo Hunter; and let’s not forget Mr. Weller senior, who says that his wife was a much better widow than she is a spouse?

The second part of the chapter, i.e. the well-prepared confrontation between Mr. Pickwick and Mr. Jingle, is described with a focus on Sam Weller in the kitchen downstairs, who makes himself agreeable with Mr. Muzzle, the cook, and Mary, when suddenly Job Trotter arrives. There is some boisterous slapstick when Job is attacked by the cook who grew indignant when Sam told her that according to Job she contemplated marrying Job. The confrontation upstairs is not quite as successful as the one in the kitchen because Mr. Jingle is not at all abashed at being found out but makes fun of the Nupkinses vanity and social ambition. He probably knows very well that the Mayor is not going to expose him publicly but to hush matters up in order to avoid a public humiliation of himself and his wife and daughter. Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter’s self-assured brazenness certainly makes Mr. Pickwick angry but this time he does not resort to violence, probably with respect to Mr. Nupkins, and he also forbids Sam to give Job a good thrashing outside.

When the Pickwickians leave the scene, Sam remembers having forgotten his hat in the kitchen, and he takes quite a long time looking for it in the company of Mary, whom he even kisses twice. The chapter then ends with the promising words: “And this was the first passage of Mr. Weller’ first love.”

QUESTIONS

Do you think that the ridicule of public (and probably pompous) persons like Mayors of middle-sized towns was especially enjoyable to the Victorian reading public? Was it considered bitter and brave satire, or rather stock humour? And how do you like it?

Once more, Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter get away relatively unscathed, and they don’t seem to have morally profited from Mr. Pickwick’s generosity. Are you satisfied with this ending, or do you think it disappointing?

ODDS AND ENDS

A Wellerism: ‘[…] Business first, pleasure arterwards, as King Richard the Third said when he stabbed the t’other king in the Tower, afore he smothered the babbies.’ – Those Wellerisms are often quite morbid, aren’t they?

Here’s WHAT HAPPENS

As soon as Sam Weller notices that they are going to take him and the Pickwickians to the house with the green garden gate that he has seen Job Trotter emerge from, his wrath gives way to curiosity as he realizes that this is a great opportunity to see what is inside that house. Immediately, his curiosity is rewarded as one of the first sights he takes in is “a very smart and pretty-faced servant-girl”, who opens the gate and who – as we learn later – is called Mary. The narrator here aptly gives an impression of human curiosity as such by describing the Victorian predecessors of smartphone gloaters as:

”[…] the mob, who, indignant at being excluded, and anxious to see what followed, relieved their feelings by kicking at the gate and ringing the bell, for an hour or two afterwards. In this amusement they all took part by turns, except three or four fortunate individuals, who, having discovered a grating in the gate, which commanded a view of nothing, stared through it with the indefatigable perseverance with which people will flatten their noses against the front windows of a chemist’s shop, when a drunken man, who has been run over by a dog-cart in the street, is undergoing a surgical inspection in the back-parlour.”

Once inside, our friends are taken into the presence of His Worship, the Mayor, who tries his hand at questioning Mr. Pickwick and his friends. However, Mr. Nupkins is very clumsy about it and often betrays a gross degree of ignorance with regard to proper proceedings that his secretary Mr. Jinks tries his best to set him right without seeming to be doing so. Matters are not made easier for the official because Mr. Weller is anything but cowed by the constable Grummer or by the Mayor himself. In a way, this scene reminded me of two things extremely unlike each other, namely of the character of Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, e.g. as presented here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82dYx...

but also, especially in the scene where the policemen try not to laugh about Sam Weller’ funny comments so as not to incur the wrath of Mr. Nupkins, this reminded me of “The Life of Brian”, where the guards try not to laugh at the rather bawdy names of Pilates’s friends. I wonder if the Monty Python people have ever read that scene from Pickwick Papers:

”‘This is a wery impartial country for justice, ‘said Sam.’ There ain’t a magistrate goin’ as don’t commit himself twice as he commits other people.’

At this sally another special laughed, and then tried to look so supernaturally solemn, that the magistrate detected him immediately.

‘Grummer,’ said Mr. Nupkins, reddening with passion, ‘how dare you select such an inefficient and disreputable person for a special constable, as that man? How dare you do it, Sir?’

‘I am very sorry, your Wash-up,’ stammered Grummer.

‘Very sorry!’ said the furious magistrate. ‘You shall repent of this neglect of duty, Mr. Grummer; you shall be made an example of. Take that fellow’s staff away. He’s drunk. You’re drunk, fellow.’

‘I am not drunk, your Worship,’ said the man.

‘You are drunk,’ returned the magistrate. ‘How dare you say you are not drunk, Sir, when I say you are? Doesn’t he smell of spirits, Grummer?’

‘Horrid, your Wash-up,’ replied Grummer, who had a vague impression that there was a smell of rum somewhere.

‘I knew he did,’ said Mr. Nupkins. ‘I saw he was drunk when he first came into the room, by his excited eye. Did you observe his excited eye, Mr. Jinks?’

‘Certainly, Sir.’

‘I haven’t touched a drop of spirits this morning,’ said the man, who was as sober a fellow as need be.

‘How dare you tell me a falsehood?’ said Mr. Nupkins. ‘Isn’t he drunk at this moment, Mr. Jinks?’

‘Certainly, Sir,’ replied Jinks.

‘Mr. Jinks,’ said the magistrate, ‘I shall commit that man for contempt. Make out his committal, Mr. Jinks.’”

It’s once again Mr. Weller who saves the day by telling Mr. Pickwick what he knows about Job Trotter’s frequenting the house of the Mayor, and in a private conference with that worthy, which is reluctantly granted, Mr. Nupkins is informed that Captain Fitz-Marshall, the acquaintance Mr. Nupkins and his wife have vaunted in the faces of all their friends, especially the – and here comes another brilliant name I don’t want to suppress – the Porkenhams, is maybe not the man he seems but a base swindler and adventurer. Apparently, this is a very embarrassing bit of news to Mr. Nupkins because they have been so impressed with Fitz-Marshall that his advances towards Miss Nupkins’s hand, in a matrimonial light, have not been looked down upon as unwelcome. Mr. Nupkins therefore demands proof from Mr. Pickwick, and this gentleman suggests, self-confidently, that he should be allowed to face Jingle-Fitz-Marshall, and then everyone could see what would happen. Mr. Nupkins agrees and forbears from any further prosecution of the Pickwickians. He then breaks the news to his wife and his daughter, who are described in these not very encouraging sentences:

”Mrs. Nupkins was a majestic female in a pink gauze turban and a light brown wig. Miss Nupkins possessed all her mamma’s haughtiness without the turban, and all her ill-nature without the wig; and whenever the exercise of these two amiable qualities involved mother and daughter in some unpleasant dilemma, as they not infrequently did, they both concurred in laying the blame on the shoulders of Mr. Nupkins.”

Again, we see that in Pickwick Papers men of public station, and very overbearing men at that, are often henpecked at home. Do you think this is a pattern whose originality and ability to amuse quickly fizzles out? Or do you see any differences between Mr. Nupkins, Mr. Pott and Mr. Leo Hunter; and let’s not forget Mr. Weller senior, who says that his wife was a much better widow than she is a spouse?

The second part of the chapter, i.e. the well-prepared confrontation between Mr. Pickwick and Mr. Jingle, is described with a focus on Sam Weller in the kitchen downstairs, who makes himself agreeable with Mr. Muzzle, the cook, and Mary, when suddenly Job Trotter arrives. There is some boisterous slapstick when Job is attacked by the cook who grew indignant when Sam told her that according to Job she contemplated marrying Job. The confrontation upstairs is not quite as successful as the one in the kitchen because Mr. Jingle is not at all abashed at being found out but makes fun of the Nupkinses vanity and social ambition. He probably knows very well that the Mayor is not going to expose him publicly but to hush matters up in order to avoid a public humiliation of himself and his wife and daughter. Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter’s self-assured brazenness certainly makes Mr. Pickwick angry but this time he does not resort to violence, probably with respect to Mr. Nupkins, and he also forbids Sam to give Job a good thrashing outside.

When the Pickwickians leave the scene, Sam remembers having forgotten his hat in the kitchen, and he takes quite a long time looking for it in the company of Mary, whom he even kisses twice. The chapter then ends with the promising words: “And this was the first passage of Mr. Weller’ first love.”

QUESTIONS

Do you think that the ridicule of public (and probably pompous) persons like Mayors of middle-sized towns was especially enjoyable to the Victorian reading public? Was it considered bitter and brave satire, or rather stock humour? And how do you like it?

Once more, Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter get away relatively unscathed, and they don’t seem to have morally profited from Mr. Pickwick’s generosity. Are you satisfied with this ending, or do you think it disappointing?

ODDS AND ENDS

A Wellerism: ‘[…] Business first, pleasure arterwards, as King Richard the Third said when he stabbed the t’other king in the Tower, afore he smothered the babbies.’ – Those Wellerisms are often quite morbid, aren’t they?

Chapter 26 is short and compact, and yet it is to do with what may develop into the overarching story-line of Pickwick Papers, seeing that each instalment gives us a little update on the misunderstanding between Mr. Pickwick and his landlady and the lawsuit that may result from it.

Having returned from his journey to Ipswich, which was, on the whole, crowned with success despite the complications in the wake of the Witherfield incident, Mr. Pickwick takes up quarters in a London hotel and sends his valet Sam on an errand to his former landlady, with two missions to discharge, nay, actually, three. Sam is to make sure that his masters belongings will be packed and got ready to be sent for, and he is also to pay Mrs. Bardell the rent, which is still due. Finally, when Sam is about to depart, Mr. Pickwick casually gives him another order, which is probably the main reason for the whole enterprise, and which Mr. Pickwick nonchalantly phrases as follows:

Well, I bet Mr. Pickwick wouldn’t object. The reader now gets a wonderfully funny episode of how Mrs. Bardell and her two friends Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Sanders meet Sam Weller. Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Sanders are two very distinctive women, for the former is “a little, brisk, busy-looking woman”, whereas the latter is “a big, fat, heavy-faced personage” and also shows signs of unrest as long as there is any danger of their unexpected guest’s partaking of the dinner Mrs. Bardell has prepared for them. Part of the fun I derived from this scene is that the two friends are clearly motivated into visiting Mrs. Bardell not so much by the abstract and noble demands of friendship but by their curiosity as to the impending lawsuit – just consider how readily they offer themselves as witnesses of the conversation between Mrs. Bardell and Sam – and even more so by the promise of a dainty dinner. And yet, Mrs. Cluppins is not over-scrupulous about interpreting her motives in a more self-denying light, thereby giving some little foretaste of Gampish oratory:

It’s equally entertaining to see how Mr. Weller manages to curry favour with the three ladies, especially with Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Bardell, so that they later come to the conclusion that the servant can hardly be blamed for the moral deficiencies of the master. What do you think of Mr. Weller’s communicative strategies? Are they really that efficient, or do you consider them rather easy to see through?

Be that as it may, through his power of charming the three ladies, Mr. Weller learns that Mrs. Bardell is determined to go through with the lawsuit, partly because she seems to be encouraged by Dodson and Fogg, who work on speculation, i.e. they will rely on being paid their expenses until the plaintiff, Mrs. Bardell, has been granted damages. The three ladies regard this as proof of Dodson and Foggs’s generosity, and Sam, of course, does not openly contradict them, but voices his encomium on the two lawyers in words that are obviously double-edged:

What do you make of Mrs. Bardell? Is she a vindictive, or even conniving person who tries to pull a fast one on Mr. Pickwick, or is she a victim of both a misunderstanding and two unscrupulous lawyers? What does the breach of promise legislation tell us about women’s position in Victorian society?

And finally, did you enjoy this funny episode as much as I did, which shows that even women in PP are not above drinking a glass of wine from time to time, though they often do it by mistake:

Having returned from his journey to Ipswich, which was, on the whole, crowned with success despite the complications in the wake of the Witherfield incident, Mr. Pickwick takes up quarters in a London hotel and sends his valet Sam on an errand to his former landlady, with two missions to discharge, nay, actually, three. Sam is to make sure that his masters belongings will be packed and got ready to be sent for, and he is also to pay Mrs. Bardell the rent, which is still due. Finally, when Sam is about to depart, Mr. Pickwick casually gives him another order, which is probably the main reason for the whole enterprise, and which Mr. Pickwick nonchalantly phrases as follows:

”‘I have no objection, Sam, to your endeavouring to ascertain how Mrs. Bardell herself seems disposed towards me, and whether it is really probable that this vile and groundless action is to be carried to extremity. I say I do not object to you doing this, if you wish it, Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick.”

Well, I bet Mr. Pickwick wouldn’t object. The reader now gets a wonderfully funny episode of how Mrs. Bardell and her two friends Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Sanders meet Sam Weller. Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Sanders are two very distinctive women, for the former is “a little, brisk, busy-looking woman”, whereas the latter is “a big, fat, heavy-faced personage” and also shows signs of unrest as long as there is any danger of their unexpected guest’s partaking of the dinner Mrs. Bardell has prepared for them. Part of the fun I derived from this scene is that the two friends are clearly motivated into visiting Mrs. Bardell not so much by the abstract and noble demands of friendship but by their curiosity as to the impending lawsuit – just consider how readily they offer themselves as witnesses of the conversation between Mrs. Bardell and Sam – and even more so by the promise of a dainty dinner. And yet, Mrs. Cluppins is not over-scrupulous about interpreting her motives in a more self-denying light, thereby giving some little foretaste of Gampish oratory:

”‘To see how dreadful she takes on, going moping about, and taking no pleasure in nothing, except when her friends comes in, out of charity, to sit with her, and make her comfortable,’ resumed Mrs. Cluppins, glancing at the tin saucepan and the Dutch oven, ‘it’s shocking!’”

It’s equally entertaining to see how Mr. Weller manages to curry favour with the three ladies, especially with Mrs. Cluppins and Mrs. Bardell, so that they later come to the conclusion that the servant can hardly be blamed for the moral deficiencies of the master. What do you think of Mr. Weller’s communicative strategies? Are they really that efficient, or do you consider them rather easy to see through?

Be that as it may, through his power of charming the three ladies, Mr. Weller learns that Mrs. Bardell is determined to go through with the lawsuit, partly because she seems to be encouraged by Dodson and Fogg, who work on speculation, i.e. they will rely on being paid their expenses until the plaintiff, Mrs. Bardell, has been granted damages. The three ladies regard this as proof of Dodson and Foggs’s generosity, and Sam, of course, does not openly contradict them, but voices his encomium on the two lawyers in words that are obviously double-edged:

”‘And of them Dodson and Foggs, as does these sort o’ things on spec,’ continued Mr. Weller, ‘as vell as for the other kind and gen’rous people o’ the same purfession, as sets people by the ears, free gratis for nothin’, and sets their clerks to work to find out little disputes among their neighbours and acquaintances as vants settlin’ by means of lawsuits—all I can say o’ them is, that I vish they had the reward I’d give ‘em.’”

What do you make of Mrs. Bardell? Is she a vindictive, or even conniving person who tries to pull a fast one on Mr. Pickwick, or is she a victim of both a misunderstanding and two unscrupulous lawyers? What does the breach of promise legislation tell us about women’s position in Victorian society?

And finally, did you enjoy this funny episode as much as I did, which shows that even women in PP are not above drinking a glass of wine from time to time, though they often do it by mistake:

”‘Here’s the receipt, Mr. Weller,’ said Mrs. Bardell, ‘and here’s the change, and I hope you’ll take a little drop of something to keep the cold out, if it’s only for old acquaintance’ sake, Mr. Weller.’

Sam saw the advantage he should gain, and at once acquiesced; whereupon Mrs. Bardell produced, from a small closet, a black bottle and a wine-glass; and so great was her abstraction, in her deep mental affliction, that, after filling Mr. Weller’s glass, she brought out three more wine-glasses, and filled them too.

‘Lauk, Mrs. Bardell,’ said Mrs. Cluppins, ‘see what you’ve been and done!’

‘Well, that is a good one!’ ejaculated Mrs. Sanders.

‘Ah, my poor head!’ said Mrs. Bardell, with a faint smile.

Sam understood all this, of course, so he said at once, that he never could drink before supper, unless a lady drank with him. A great deal of laughter ensued, and Mrs. Sanders volunteered to humour him, so she took a slight sip out of her glass. Then Sam said it must go all round, so they all took a slight sip. Then little Mrs. Cluppins proposed as a toast, ‘Success to Bardell agin Pickwick’; and then the ladies emptied their glasses in honour of the sentiment, and got very talkative directly.”

Tristram wrote: "There was a boxer with a very strange name in another Dickens novel, but at the moment it eludes me which novel it was. But the name had something to do with a chicken, like “the Suffolk Bantam”...."

Tristram wrote: "There was a boxer with a very strange name in another Dickens novel, but at the moment it eludes me which novel it was. But the name had something to do with a chicken, like “the Suffolk Bantam”...."The boxer you're thinking of, Tristram, was from Dombey and Son. David Perdue's wonderful website has this entry on him:

Game Chicken, The ( Dombey and Son ) Boxer that Toots hires to teach him the art. A stoical gentleman in a shaggy white great-coat and a flat-brimmed hat, with very short hair, a broken nose, and a considerable tract of bare and sterile country behind each ear." He "knocked Mr Toots about the head three times a week, for the small consideration of ten and six per visit. "

I can only think that the prevalence of cock fighting made chicken nick-names popular for boxers in that era.

Tristram wrote: "and here comes another brilliant name I don’t want to suppress – the Porkenhams..."

Tristram wrote: "and here comes another brilliant name I don’t want to suppress – the Porkenhams..."We talked last week about listening v. reading. This is a good example of what you can miss without the written word. This name flew right by me. I'm so glad you called attention to it here!

Tristram wrote: "Would it really have been so disastrous for Miss Witherfield’s reputation if she and Mr. Pickwick had solved the mystery of their meeting the night before? How would Mr. Magnus have reacted? Could he have taken any offence by Victorian standards?..."

Tristram wrote: "Would it really have been so disastrous for Miss Witherfield’s reputation if she and Mr. Pickwick had solved the mystery of their meeting the night before? How would Mr. Magnus have reacted? Could he have taken any offence by Victorian standards?..."For me, this kind of sums up one of the big themes of the novel, i.e. miscommunications. So many of Pickwick's stories could be easily resolved if only people were straightforward and not so very concerned about propriety. Of course, then we would have a very short, and rather dull, book!

Tristram wrote: "In this chapter, he wears green glasses, being the green-eyed monster of jealousy that he is, but when Mr. Pickwick first meets him, we wears blue glasses. ..."

Tristram wrote: "In this chapter, he wears green glasses, being the green-eyed monster of jealousy that he is, but when Mr. Pickwick first meets him, we wears blue glasses. ..."Another continuity mistake? Does this point to Dickens' comparative immaturity as an author? Shoddy editing? As complex as his later novels were, I don't recall any continuity problems, which is kind of miraculous, really. The curse of authors who develop immense popularity and cult followers -- they couldn't possibly have known as they were writing how fans would one day parse every word!

(PS Or perhaps Magnus is just like a woman with whom I work, who likes to accessorize with her eyewear, and has glasses in every color of the rainbow. :-) )

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

By now, we might have gained so much knowledge of Mr. Pickwick and his friends’ propensity for the creation of trouble and misunderstandings – after all, Mr. Pickwick himself mad..."

The PP certainly has a focus on love and marriage. The Magnus episode is enjoyable and it further develops the character of Pickwick. To counterbalance the tropes of marriage Dickens blends in confusion, misdirection, and just enough bitterness to give his chapters grit, but grit lacking in any caustic endings.

Dickens was in his early 20’s when the sections of PP were being written. He was recently married and still in love with his wife. So, my question is, where did such a young writer come up with such a variety of love matches and entanglements?

Could it be possible that his work at the lawyer’s office and then his reporting job given him access to the vagrances of the human heart, and that these contacts were reconstituted in his novel? Dickens is a much more worldly man of experience than most other men of his age. His natural ability to write was then merged with his keen eyes and ears of observation to produce his writing.

I think that another of Dickens’s tutors was the theatre. He loved the broad humour of actors such as Charles Mathews. Also, the theatre would have exposed Dickens to the concept and staging of the French Farce. The antic, energetic, and often misaligned emotions of the Farce would suit Dickens’s sense of humour. By combining his early experiences as an apprentice lawyer/reporter with his knowledge of 19C theatre and his gift of writing skill he was able to write PP.

By now, we might have gained so much knowledge of Mr. Pickwick and his friends’ propensity for the creation of trouble and misunderstandings – after all, Mr. Pickwick himself mad..."

The PP certainly has a focus on love and marriage. The Magnus episode is enjoyable and it further develops the character of Pickwick. To counterbalance the tropes of marriage Dickens blends in confusion, misdirection, and just enough bitterness to give his chapters grit, but grit lacking in any caustic endings.

Dickens was in his early 20’s when the sections of PP were being written. He was recently married and still in love with his wife. So, my question is, where did such a young writer come up with such a variety of love matches and entanglements?

Could it be possible that his work at the lawyer’s office and then his reporting job given him access to the vagrances of the human heart, and that these contacts were reconstituted in his novel? Dickens is a much more worldly man of experience than most other men of his age. His natural ability to write was then merged with his keen eyes and ears of observation to produce his writing.

I think that another of Dickens’s tutors was the theatre. He loved the broad humour of actors such as Charles Mathews. Also, the theatre would have exposed Dickens to the concept and staging of the French Farce. The antic, energetic, and often misaligned emotions of the Farce would suit Dickens’s sense of humour. By combining his early experiences as an apprentice lawyer/reporter with his knowledge of 19C theatre and his gift of writing skill he was able to write PP.

Re. boxing and chickens:

Re. boxing and chickens:"Dickens enjoyed the language of boxing as much as he did boxers, and nowhere more than in Dombey and Son (1846-8); indeed he stole the name (but little else) of a real prize-fighter, ‘The Game Chicken’ (Henry - ‘Hen’ - Pearce) for one of its characters. After coming into his inheritance, Mr Toots, a Corinathian past his sell-by-date, devotes himself to learning ‘those gentle arts which refine and humanise existence, his chief instructor in which was an interesting character called the Game Chicken, who was always heard of at the bar of the Black Badger, wore a shaggy great-coat in the warmest weather, and knocked Mr. Toots about the head three times a week, for the small consideration of ten and six per visit.’ We learn about the Game Chickens’s past exploits, his glory against the Nobby Shropshire One, and his defeat (‘he was severely fibbed . . . heavily grassed’) by the Larkey Boy. When Mr Toots despairs of winning the love of Florence Dombey against the wishes of her father, the Chicken reassures him that ‘it is within the resources of Science to double him up, with one blow in the waistcoat.’"

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 25 is rather long, as can already guessed from the introductory title, and in it, the narrator brings the Ipswich episode to a close by showing us how Mr. Pickwick and his friends extricate..."

I totally agree with you Tristram. Monty Python and PP do seem to come from the same well of humour, exaggerated personalities, and stagecraft.

The green door seems to be a portal. On the one hand, behind the door is found the world of politics, law and order. These traits of civilization are rendered into a different state of being. Much like Alice’s rabbit hole, where we find there are people, creatures, and settings that are, at once, the same as and dissimilar, the green door acts as both a separation and an entry point.

The green door is the most prominent feature of the house. It is also the place that Sam must pass through in order to see Mary. As Tristram noted, the ending of this chapter teases the reader. Has Sam found someone to love? If so, this will be yet another addition to our ever-growing number of love affairs. The difference will be that if Sam and Mary further develop their attachment to each other, Dickens will have provided himself another layer to the trope of love in the novel. We would then be able to watch the development of two characters from a lower social order and contrast it to the love emotions of the higher classes.

I totally agree with you Tristram. Monty Python and PP do seem to come from the same well of humour, exaggerated personalities, and stagecraft.

The green door seems to be a portal. On the one hand, behind the door is found the world of politics, law and order. These traits of civilization are rendered into a different state of being. Much like Alice’s rabbit hole, where we find there are people, creatures, and settings that are, at once, the same as and dissimilar, the green door acts as both a separation and an entry point.

The green door is the most prominent feature of the house. It is also the place that Sam must pass through in order to see Mary. As Tristram noted, the ending of this chapter teases the reader. Has Sam found someone to love? If so, this will be yet another addition to our ever-growing number of love affairs. The difference will be that if Sam and Mary further develop their attachment to each other, Dickens will have provided himself another layer to the trope of love in the novel. We would then be able to watch the development of two characters from a lower social order and contrast it to the love emotions of the higher classes.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 26 is short and compact, and yet it is to do with what may develop into the overarching story-line of Pickwick Papers, seeing that each instalment gives us a little update on the misunderst..."

I think Mrs Bardell is a stock character, the long self-suffering woman whose chosen to reach back into the past in order to survive on memories while at the same time hope that Cupid will have another arrow in his quiver and thus grant her a future. I find she is serious and subject to her own fantasies. I do not think she is a black widow like Mrs MacStinger in D&S.

I think Mrs Bardell is a stock character, the long self-suffering woman whose chosen to reach back into the past in order to survive on memories while at the same time hope that Cupid will have another arrow in his quiver and thus grant her a future. I find she is serious and subject to her own fantasies. I do not think she is a black widow like Mrs MacStinger in D&S.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 26 is short and compact, and yet it is to do with what may develop into the overarching story-line of Pickwick Papers, seeing that each instalment gives us a little update ..."

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 26 is short and compact, and yet it is to do with what may develop into the overarching story-line of Pickwick Papers, seeing that each instalment gives us a little update ..."I can almost feel sorry for Mrs Bardell, who deceives herself about Pickwick's intentions, and then even as she's suing him she seems sad to see him break off his lease: "'Whatever has happened,' said Mrs Bardell, 'I always have said, and always will say, that in every respect but one, Mr Pickwick has always behaved himself like a perfect gentleman.'" She's presented as manipulated by her lawyers first and then her friends Sanders and Cluppins, all of whom are eager for conflict.

But I can't feel too sorry for her. She's either extremely foolish or predisposed to be manipulated for her own gain. Poor hapless Pickwick, caught in all that.

Hi guys, I haven't been feeling very well these last few days (weeks?), and I haven't made my usual search for illustrations, but I thought I'd give you the ones I already had. Sorry for the gap in them.

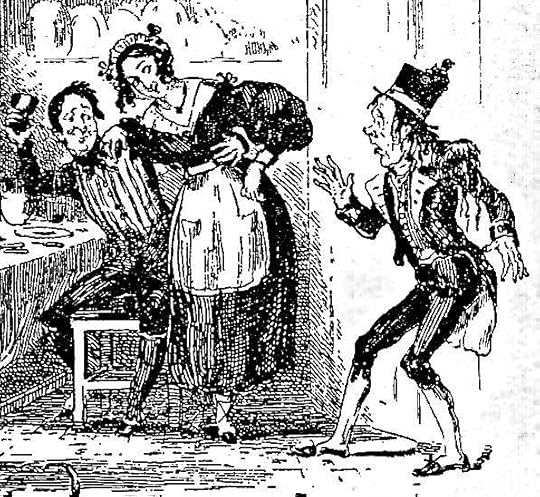

Mr. Weller Attacks the Executive of Ipswich

Chapter 24

Phiz - 1836

Text Illustrated:

The presence of a sedan chair suggests a Regency or even an eighteenth-century setting for both the passage and its accompanying illustration which captures well the sense of uproarious discord of a brawling crowd scene like something out of Hogarth in the following:

Whether Mr. Winkle was seized with a temporary attack of that species of insanity which originates in a sense of injury, or animated by this display of Mr. Weller's valour, is uncertain; but certain it is, that he no sooner saw Mr. Grummer fall than he made a terrific onslaught on a small boy who stood next him; whereupon Mr. Snodgrass, in a truly Christian spirit, and in order that he might take no one unawares, announced in a very loud tone that he was going to begin, and proceeded to take off his coat with the utmost deliberation. He was immediately surrounded and secured; and it is but common justice both to him and Mr. Winkle to say, that they did not make the slightest attempt to rescue either themselves or Mr. Weller; who, after a most vigorous resistance, was overpowered by numbers and taken prisoner. The procession then reformed; the chairmen resumed their stations; and the march was re-commenced.

Mr. Pickwick's indignation during the whole of this proceeding was beyond all bounds. He could just see Sam upsetting the specials, and flying about in every direction; and that was all he could see, for the sedan doors wouldn’t open, and the blinds wouldn’t pull up. At length, with the assistance of Mr. Tupman, he managed to push open the roof; and mounting on the seat, and steadying himself as well as he could, by placing his hand on that gentleman’s shoulder, Mr. Pickwick proceeded to address the multitude; to dwell upon the unjustifiable manner in which he had been treated; and to call upon them to take notice that his servant had been first assaulted. In this order they reached the magistrate’s house; the chairmen trotting, the prisoners following, Mr. Pickwick oratorising, and the crowd shouting. [chapter 24]

Mr. Weller Attacks the Executive of Ipswich

Chapter 24

Phiz - 1836

Text Illustrated:

The presence of a sedan chair suggests a Regency or even an eighteenth-century setting for both the passage and its accompanying illustration which captures well the sense of uproarious discord of a brawling crowd scene like something out of Hogarth in the following:

Whether Mr. Winkle was seized with a temporary attack of that species of insanity which originates in a sense of injury, or animated by this display of Mr. Weller's valour, is uncertain; but certain it is, that he no sooner saw Mr. Grummer fall than he made a terrific onslaught on a small boy who stood next him; whereupon Mr. Snodgrass, in a truly Christian spirit, and in order that he might take no one unawares, announced in a very loud tone that he was going to begin, and proceeded to take off his coat with the utmost deliberation. He was immediately surrounded and secured; and it is but common justice both to him and Mr. Winkle to say, that they did not make the slightest attempt to rescue either themselves or Mr. Weller; who, after a most vigorous resistance, was overpowered by numbers and taken prisoner. The procession then reformed; the chairmen resumed their stations; and the march was re-commenced.

Mr. Pickwick's indignation during the whole of this proceeding was beyond all bounds. He could just see Sam upsetting the specials, and flying about in every direction; and that was all he could see, for the sedan doors wouldn’t open, and the blinds wouldn’t pull up. At length, with the assistance of Mr. Tupman, he managed to push open the roof; and mounting on the seat, and steadying himself as well as he could, by placing his hand on that gentleman’s shoulder, Mr. Pickwick proceeded to address the multitude; to dwell upon the unjustifiable manner in which he had been treated; and to call upon them to take notice that his servant had been first assaulted. In this order they reached the magistrate’s house; the chairmen trotting, the prisoners following, Mr. Pickwick oratorising, and the crowd shouting. [chapter 24]

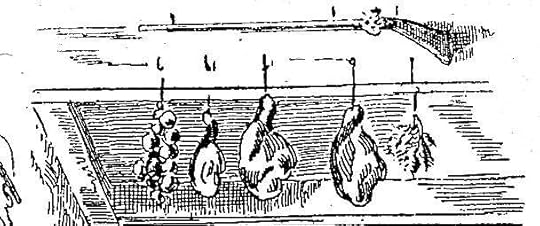

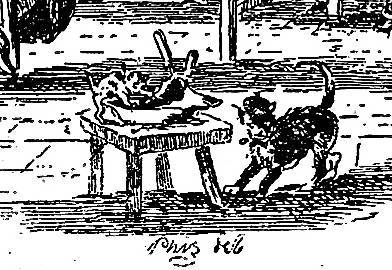

Job Trotter encounters Sam in Mr. Muzzle's kitchen

Chapter 25

Phiz 1836

Commentary:

Phiz has realised the early nineteenth-century kitchen in loving detail, with a roaring fire to the left and garlic and cured meats hanging above a scene of plenty and conviviality which Jingle's manservant in mulberry-coloured livery, a former actor accustomed to exaggerating his tearful emotions, now enters:

In the midst of all this jollity and conviviality, a loud ring was heard at the garden gate, to which the young gentleman who took his meals in the wash-house, immediately responded. Mr. Weller was in the height of his attentions to the pretty house- maid; Mr. Muzzle was busy doing the honours of the table; and the cook had just paused to laugh, in the very act of raising a huge morsel to her lips; when the kitchen door opened, and in walked Mr. Job Trotter. [chapter 25]

The picture's emphasis on physical and situation humour reminds us that we are still in the world of the Regency, when Dickens wrote such comic "Sketches" as "Horatio Sparkins" (February 1834) for The Monthly Magazine and The Morning Chronicle, and his lightweight romantic comedies such as Is She His Wife? Or, Something Singular (6 March 1837 at London's St. James's Theatre). In this scene we are still very much in the world of the episodic, picaresque novel.

Details to be aware of (I don't know why we're supposed to be aware of them, but they said so, I didn't) are Job Trotter, the rifle and hams, and the dog and cat:

Job Trotter, which I think was pretty obvious without the enlargement.

The rifle and hams which were not obvious to me, but I'm usually busy copying the illustrations not looking at them. :-)

and finally, the dog and the cat

Mr. Pickwick no sooner put on his spectacles, than he at once recognised in the future Mrs. Magnus the lady into whose room he had so unwarrantably intruded on the previous night.

Chapter 24

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

By the light of day in the inn at Ipswich, and with his spectacles on, Pickwick recognises the lady in the curl-papers from the previous night's misadventure as his travelling companion Peter Magnus's fiancee, Miss Witherfield. Although Nast's juxtaposition of the figures more accurately reflects Dickens's description, with Miss Withfield at the upper end of the room rather than opposite Peter Magnus, Phiz's dressing of the stage, so to speak, is superior, with the figures better distributed, the room more effectively furnished, and Pickwick's look of recognition — in contrast to the obvious surprise of Peter Magnus and Miss Witherfield — highly believable. The scene realised involves Peter Magnus's dragging Mr. Pickwick down the hall to meet the woman who has just agreed to be his wife; until the ensuing introduction it has not occurred to Pickwick that the fiancee and the lady in the curl-papers from much earlier that morning might possibly be one-and-the-same person:

"You must see her, sir," said Mr. Magnus; "this way, if you please. Excuse us for one instant, gentlemen." Hurrying on in this way, Mr. Peter Magnus drew Mr. Pickwick from the room. He paused at the next door in the passage, and tapped gently thereat.

"Come in!" said a female voice. And in they went.

"Miss Witherfield," said Mr. Magnus. "Allow me to introduce my very particular friend, Mr. Pickwick. Mr. Pickwick, I beg to make you known to Miss Witherfield."

The lady was at the upper end of the room. As Mr. Pickwick bowed, he took his spectacles from his waistcoat pocket, and put them on; a process which he had no sooner gone through, than, uttering an exclamation of surprise, Mr. Pickwick retreated several paces, and the lady, with a half-suppressed scream, hid her face in her hands, and dropped into a chair: whereupon Mr. Peter Magnus was stricken motionless on the spot, and gazed from one to the other, with a countenance expressive of the extremities of horror and surprise. This certainly was, to all appearance, very unaccountable behaviour; but the fact is, that Mr. Pickwick no sooner put on his spectacles, than he at once recognised in the future Mrs. Magnus the lady into whose room he had so unwarrantably intruded on the previous night; and the spectacles had no sooner crossed Mr. Pickwick's nose, than the lady at once identified the countenance which she had seen surrounded by all the horrors of a nightcap. So the lady screamed, and Mr. Pickwick started.

"Mr. Pickwick!’ exclaimed Mr. Magnus, lost in astonishment. "What is the meaning of this, sir? What is the meaning of it, sir?" added Mr. Magnus, in a threatening, and a louder tone.

"Sir,’ said Mr. Pickwick, somewhat indignant at the very sudden manner in which Mr. Peter Magnus had conjugated himself into the imperative mood, "I decline answering that question."

"You decline it, sir?" said Mr. Magnus.

"I do, Sir," replied Mr. Pickwick; "I object to say anything which may compromise that lady, or awaken unpleasant recollections in her breast, without her consent and permission."

"Miss Witherfield," said Mr. Peter Magnus, "do you know this person?"

"Know him!" repeated the middle-aged lady, hesitating.

"Yes, know him, ma'am; I said know him" replied Mr. Magnus, with ferocity.

"I have seen him," replied the middle-aged lady.

"Where?" inquired Mr. Magnus, "where?"

"That," said the middle–aged lady, rising from her seat, and averting her head, "that would not reveal for worlds."

‘I understand you, ma’am,’ said Mr. Pickwick, "and respect your delicacy; it shall never be revealed by me depend upon it."

Here, then, is yet another scene that Phiz did not attempt in his orginal 1836-37 serial program, but which obviously stimulated his imagination. In terms of the narrative-pictorial sequence, the "recognition" scene sets up the brawl in the market-place after Magistrate George Nupkins has issued a warrant for the arrest of Pickwick, based on Miss Witherfield's testimony. She has approached the magistrate after the verbal altercation between Magnus and Pickwick at the inn since she erroneously believes that the two are about to fight a duel over her, and that the only way of preserving her fiance's life is to have Pickwick incarcerated. Phiz's three figures, though frozen in a tableau vivant at the inception of the complications, are more believable than the cartoon-like figures offered by Nast, who has elected to show Miss Witherfield hiding her face in her hands after she has recognized in her future husband's friend the trespasser of a few hours before. Whereas in his earlier work, Phiz tended to include both pictorial and textual comments within his compositions, the only detail that could be construed as an emblem here is the romantic landscape painting that separates the middle-aged gentlemen. The castle on a hill may be intended to signify the age of chivalry long gone in which noblemen routinely fought duels to preserve that chimera "honour" or "reputation." Whereas Pickwick and Miss Witherfield extent their arms out and downward in recognition, Magnus gestures upward with his right hand, as if inviting explanation from Pickwick. Pickwick's foolishly trying to preserve Miss Witherfield's honour by remaining mum only fuels Magnus's suspicions.

"What is the meaning of this, sir?"

Chapter 24

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Thomas Nast created 52 illustrations for the 1873 Household Edition of Pickwick Papers issued by Harper & Bros., New York. Typically, these illustrations, with the exception of a few full-page character studies, are set horizontally in the middle of a page and are 10.3 cm high by 13.4 cm high on a double-columned page approximately 21 cm high. Thus, each plate occupies approximately half of the page. The print is sharp, but quite fine, so that the entire book is 332 pages, exclusive of a four-page Harper's "advertiser" for its "Valuable Standard Works." In contrast, the British Household Edition is printed on heavier paper, has larger type, and each page is frame as well as double-columned, in more accurate imitation of the original Household Words format. With larger type, the Chapman and Hall text is 400 pages (there is no "advertiser"). In size and juxtaposition on the page, Phiz's fifty-seven illustrations are similar to Nast's fifty-two. However, Chapman and Hall provide a two-and-a-half page index (pp. x-xii) to Phiz's illustrations, while the Harper and Brothers' text has no such index for Nast's. Phiz has provided four full-page illustrations, running about one to one hundred pages of letter-press; Nast begins with two full-page illustrations, then provides three others throughout the text.

"A compliment which Mr. Weller returned by knocking him down out of hand: having previously, with the utmost consideration, knocked down a chairman for him to lie upon.

Chapter 24

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

In Ipswich, the town in Suffolk to which Mr. Pickwick and Sam have pursued the nefarious Alfred Jingle after his appearance at Mrs. Leo Hunter's garden party at Eatanswill, the Pickwickians rent rooms at the Great White Horse Inn. Mistaking Miss Witherfield's room for his own after getting lost in the maze of corridors after midnight, Pickwick finds himself in highly embarrassing circumstances yet again. Accused by the "middle-aged lady in yellow curl-papers" of being a political agitator, and brought before the local magistrate, the wrong-headed old Tory Mr. Nupkins, Pickwick eventually uses his knowledge that Nupkins, too, has been taken in by Jingle to leverage his own release and that of Sam, even though the pair have been involved in a physical altercation with the authorities in the market place after Sam attempted to effect his master's rescue by assaulting the preposterous constable, Grummer (fallen to the ground and touching his head gingerly in the foreground, left, his baton of office momentarily cast aside).

As is typical of the scenes which Phiz revised from the original illustrations, in the battle between Sam Weller and the civic authorities at Ipswich in defence of Pickwick, the Household Edition illustrator has moved in for a close-up, so that the details of surrounding houses are lost, and Pickwick's head, formerly in the centre of the composition, now touches the top frame. Then, too, Phiz has sacrificed something of the original's Hogarthian exuberance in redrafting the scene in the manner of the Sixties Illustrators, reducing the number of figures (all now much more substantial) from twelve in the foreground of the December 1836 engraving to nine in the 1873 woodcut, and somewhat reducing Sam Weller's presence, for Sam (below, right) and Pickwick (above, centre), who dominate the earlier. Other figures immediately recognisable are Mr. Snodgrass (left, with his coat off the shoulder, as if making to fight, although he has no intention of doing so) and the other special constable, Mr. Dubbley (centre, in front of the sedan chair), in the surtout, ineffectually defending himself against Sam Weller's right jab. A significant shift in his conception of Pickwick in this scene is evident in the Household Edition woodcut, for Pickwick, formerly argumentative and indignant as he clambers up to the roof of the sedan chair to make his grievance heard, now seems somewhat aghast at the mayhem Sam has caused in trying to liberate him. The continued presence of the somewhat oversized sedan chair in both earlier and later versions suggests a Regency or even an eighteenth-century setting for both the passage and its accompanying illustration which captures well the sense of uproarious discord of a brawling crowd scene like something out of the William Hogarthseries entitled "The Election" (particularly "The Chairing of the Candidate") in the following:

Whether Mr. Winkle was seized with a temporary attack of that species of insanity which originates in a sense of injury, or animated by this display of Mr. Weller's valour, is uncertain; but certain it is, that he no sooner saw Mr. Grummer fall than he made a terrific onslaught on a small boy who stood next him; whereupon Mr. Snodgrass, in a truly Christian spirit, and in order that he might take no one unawares, announced in a very loud tone that he was going to begin, and proceeded to take off his coat with the utmost deliberation. He was immediately surrounded and secured; and it is but common justice both to him and Mr. Winkle to say, that they did not make the slightest attempt to rescue either themselves or Mr. Weller; who, after a most vigorous resistance, was overpowered by numbers and taken prisoner. The procession then reformed; the chairmen resumed their stations; and the march was re-commenced.

Mr. Pickwick's indignation during the whole of this proceeding was beyond all bounds. He could just see Sam upsetting the specials, and flying about in every direction; and that was all he could see, for the sedan doors wouldn’t open, and the blinds wouldn’t pull up. At length, with the assistance of Mr. Tupman, he managed to push open the roof; and mounting on the seat, and steadying himself as well as he could, by placing his hand on that gentleman’s shoulder, Mr. Pickwick proceeded to address the multitude; to dwell upon the unjustifiable manner in which he had been treated; and to call upon them to take notice that his servant had been first assaulted. In this order they reached the magistrate’s house; the chairmen trotting, the prisoners following, Mr. Pickwick oratorising, and the crowd shouting.

The kitchen door opened, and in walked Mr. Job Trotter

Chapter 25

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

To illustrate the startled Job Trotter's suddenly encountering Mr. Pickwick's servant, Sam Weller, after deceiving him about his master, Alfred Jingle's intention to run away with a school-girl from Miss Tompkins' seminary, Phiz merely had to redraft his own 1836 illustration for Ch. 25. Thomas Nast, having also the 1836 model before him, elected to realise a slightly later moment in the same scene, when Muzzle and Weller begin to interrogate and berate the hapless Trotter. Nast's rendition is unusual for the illustrations in his series of fifty-two in that it contains a good deal more detail than his others, which usually focus on the figures: significantly, a gridiron hangs above Job's head (as he is being grilled from two different directions), and pots, pans, plate, and the kitchen cooking fire complete Nast's version of the scene. Even Phiz in his 1873 woodcut does not include more detail, although he has better realised the ladies and made Trotter less of a caricature.

The original illustration, "Job Trotter encounters Sam in Mr. Muzzle's kitchen" (December 1836), was oriented so that, counter to Regency stage convention, Job is entering from stage left. Phiz has sketched in the five figures heavily, using fainter etching to throw the kitchen background into less sharp relief, but including all the appurtenances of a servants' hall-cum-kitchen in a nineteenth-century country mansion, with a pot steaming over a roaring blaze (left), four liveried servants (Muzzle doing the honours at the board, Sam seated, the maid standing beside him, and Job Trotter, just entering from the garden), cooking implements (up right), plate on a sideboard, a grandfather clock (suggesting that it is just before noon), and hams and garlic cloves hanging from the ceiling. Steig's Dickens and Phiz notes the importance of emblematic details and juxtapositions in this second December 1836 illustration, and its connection to the previous illustration, when Sam Weller attempts to rescue Pickwick from the constables in "Mr. Weller Attacks the Executive of Ipswich", the first illustration for the December 1836 monthly number:

Sam's temporary victory in this plate is contrasted with his permanent one over Job Trotter in its companion, "Job Trotter encounters Sam in Mr. Muzzle's kitchen" (ch. 25). Sam and the pretty housemaid are noticed first, then the feasting cook, butler and the former pair are contrasted with Job — his head preposterously big, like certain comic-grotesque figures in Gillray and George Cruikshank — who is isolated from the group by the vertical line formed by the door's edge; Job is also farthest from the hearth. We find as well the third of several animal emblems in the book: a kitten attacks the remains of a meat pie, while its mother prepares to join in. This activity may be a reference to Jingle and Trotter and their attempt to carry off treasures from the Nupkins household, but while fragments of food have been left out for the cats, Job is excluded from the fellowship of the servants' kitchen.

Having deduced that Jingle's latest scheme involves Henrietta, the daughter of Magistrate Nupkins, Sam leaves the serious business of unmasking Jingle to those "above stairs" and begins to make himself comfortable in Mr. Muzzle's kitchen, becoming quite a favourite with the cook and the serving-girl, Mary. Even as his master and the Pickwickians are confronting "Captain Fitz-Marshall" above stairs, quite by conicidence Job Trotter enters the kitchen, but apparently is so stunned by the sight that greets him that he does not make to escape. Sam prevents the hypocritical servant's from exiting, interrogates him, then takes him upstairs to join his master for Nupkins's judgment.

In this eleventh redrafted illustration from the original series (Phiz having revised thirty of the original forty-three 1836-37 engravings as woodcuts for the 1874 Chapman and Hall Household Edition of the novel) "The kitchen door opened, and in walked Mr. Job Trotter," Alfred Jingle's devious servant in mulberry livery, Job Trotter, suddenly finds himself trapped in Muzzle's kitchen by an irate butler and a very knowing Sam Weller. Phiz has corrected his earlier engraving by reversing the scene: Job enters stage right (the viewer's left), the cook is seated in the middle of the scene rather than to one side, and Sam and Mary are to the extreme right (i. e. stage left), far removed from the kitchen door. The problem that Dickens would have detected right away, had he been available for consultation, is that Sam is now too far away from Job to collar him, drag him into the kitchen, and lock the door. In redrafting the 1836 engraving Phiz has also eliminated the roaring fire, the utensils (both presumably off right), and even the cats (replaced by vegetables in a basket and a pot, down right), which Steig feels had symbolic significance. Further, the clock has moved several feet to the left, and now reads (more probably) 12:40 P. M. instead of 11:50 A. M. Although the cook now smiles at Trotter, Muzzle (formerly smiling at Sam and Mary) now scowls at the visitor, whose body language no longer betokens shocked recognition so much as doubt at the reception he will receive since Sam Weller has probably shed considerable light on the "mulberry man's" shady character.

"Well, now, " said Sam

Chapter 25

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Well, here’s a game!’ cried Sam. ‘Only think o’ my master havin’ the pleasure o’ meeting yourn upstairs, and me havin’ the joy o’ meetin’ you down here. How are you gettin’ on, and how is the chandlery bis’ness likely to do? Well, I am so glad to see you. How happy you look. It’s quite a treat to see you; ain’t it, Mr. Muzzle?’

‘Quite,’ said Mr. Muzzle.

‘So cheerful he is!’ said Sam.

‘In such good spirits!’ said Muzzle.

‘And so glad to see us—that makes it so much more comfortable,’ said Sam. ‘Sit down; sit down.’

Mr. Trotter suffered himself to be forced into a chair by the fireside. He cast his small eyes, first on Mr. Weller, and then on Mr. Muzzle, but said nothing.

‘Well, now,’ said Sam, ‘afore these here ladies, I should jest like to ask you, as a sort of curiosity, whether you don’t consider yourself as nice and well-behaved a young gen’l’m’n, as ever used a pink check pocket-handkerchief, and the number four collection?’

‘And as was ever a-going to be married to a cook,’ said that lady indignantly. ‘The willin!’

‘And leave off his evil ways, and set up in the chandlery line arterwards,’ said the housemaid.

‘Now, I’ll tell you what it is, young man,’ said Mr. Muzzle solemnly, enraged at the last two allusions, ‘this here lady (pointing to the cook) keeps company with me; and when you presume, Sir, to talk of keeping chandlers’ shops with her, you injure me in one of the most delicatest points in which one man can injure another. Do you understand that, Sir?’

Here Mr. Muzzle, who had a great notion of his eloquence, in which he imitated his master, paused for a reply.

But Mr. Trotter made no reply. So Mr. Muzzle proceeded in a solemn manner—

‘It’s very probable, sir, that you won’t be wanted upstairs for several minutes, Sir, because my master is at this moment particularly engaged in settling the hash of your master, Sir; and therefore you’ll have leisure, Sir, for a little private talk with me, Sir. Do you understand that, Sir?’

Mr. Muzzle again paused for a reply; and again Mr. Trotter disappointed him.

‘Well, then,’ said Mr. Muzzle, ‘I’m very sorry to have to explain myself before ladies, but the urgency of the case will be my excuse. The back kitchen’s empty, Sir. If you will step in there, Sir, Mr. Weller will see fair, and we can have mutual satisfaction till the bell rings. Follow me, Sir!’

Mr. Nupkins's Court

Chapter 25

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Commentary:

In this full-page illustration, the secondary characters who support the dictatorial old Tory George Nupkins, the "pale, sharp-nosed, half-fed, shabbily clad clerk" (200) Jinks (right) and his subordinate Muzzle, are purely incidental; rather, Eytinge focuses on the imperious and paranoid pre-1832 Great Reform Bill local magistrate who fears every perpetrator of a crime is a radical and that most of the charges he adjudicates are politically motivated. Like a worn-out John Bull, George Nupkins as Eytinge conceives of him appears in the following passage of the compact American "Diamond Edition," in which Mr. Muzzle ushers Mr. Pickwick and his companions into the "worshipful presence of that public-spirited officer" (205), sitting magisterially in his easy chair. He was "frowning with majesty and boiling with rage" even before Miss Witherfield, "the middle-aged lady," accused Pickwick and Tupman of wanting to challenge her fiancé, Peter Magnus, to a duel. Now the Ipswich executive, incensed at the possibility of these "London cut-throats" starting a riot, has had a posse of special constables under the direction of Grummer arrest the accused, who now stand before him:

The scene was an impressive one, well calculated to strike terror to the hearts of culprits, and to impress them with an adequate idea of the stern majesty of the law. In front of a big book-case, in a big chair, behind a big table, and before a big volume, sat Mr. Nupkins, looking a full size larger than any one of them, big as they were. The table was adorned with piles of papers; and above the farther end of it, appeared the head and shoulders of Mr. Jinks, who was busily engaged in looking as busy as possible. The party having all entered, Muzzle carefully closed the door, and placed himself behind his master's chair to await his orders. Mr. Nupkins threw himself back with thrilling solemnity, and scrutinised the faces of his unwilling visitors.

In the longer programs of illustration — those by Seymour and Browne (1836-37), Browne in the British Household Edition (1873), and Nast in the American Household Edition, the equivalent scene is "Mr. Weller Attacks the Executive of Ipswich" by Phiz (ch. 24) for December 1836, a far more boisterous composition altogether.

However, the juxtaposition of illustration and text would suggest that Eytinge has in mind a further part of the scene in Nupkins's court, when Pickwick requests a private interview with the magistrate. Nupkins, fearing that Sam has news of an assassination plot, agrees. Subsequent, then, to the courtroom scene illustrated, Pickwick denounces the magistrate's guest, Captain Fitz-Marshall, as "An unprincipled adventurer" and confidence man, and then recounts Jingle's misdemeanours. This revelation proves sufficient for Nupkins to reverse his judgment and remit the fines.

"I suppose you've heard what's going forward, Mr. Weller?" said Mrs. Bardell.

Chapter 26

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Editon

Text Illustrated:

‘I suppose you’ve heard what’s going forward, Mr. Weller?’ said Mrs. Bardell.

‘I’ve heerd somethin’ on it,’ replied Sam.

‘It’s a terrible thing to be dragged before the public, in that way, Mr. Weller,’ said Mrs. Bardell; ‘but I see now, that it’s the only thing I ought to do, and my lawyers, Mr. Dodson and Fogg, tell me that, with the evidence as we shall call, we must succeed. I don’t know what I should do, Mr. Weller, if I didn’t.’

The mere idea of Mrs. Bardell’s failing in her action, affected Mrs. Sanders so deeply, that she was under the necessity of refilling and re-emptying her glass immediately; feeling, as she said afterwards, that if she hadn’t had the presence of mind to do so, she must have dropped.

‘Ven is it expected to come on?’ inquired Sam.

‘Either in February or March,’ replied Mrs. Bardell.

‘What a number of witnesses there’ll be, won’t there?’ said Mrs. Cluppins.

‘Ah! won’t there!’ replied Mrs. Sanders.

‘And won’t Mr. Dodson and Fogg be wild if the plaintiff shouldn’t get it?’ added Mrs. Cluppins, ‘when they do it all on speculation!’

‘Ah! won’t they!’ said Mrs. Sanders.

‘But the plaintiff must get it,’ resumed Mrs. Cluppins.

‘I hope so,’ said Mrs. Bardell.

‘Oh, there can’t be any doubt about it,’ rejoined Mrs. Sanders.

‘Vell,’ said Sam, rising and setting down his glass, ‘all I can say is, that I vish you may get it.’

‘Thank’ee, Mr. Weller,’ said Mrs. Bardell fervently.

‘And of them Dodson and Foggs, as does these sort o’ things on spec,’ continued Mr. Weller, ‘as vell as for the other kind and gen’rous people o’ the same purfession, as sets people by the ears, free gratis for nothin’, and sets their clerks to work to find out little disputes among their neighbours and acquaintances as vants settlin’ by means of lawsuits—all I can say o’ them is, that I vish they had the reward I’d give ‘em.’

Mrs. Bardell and friends

Chapter 26

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Commentary:

In this full-page illustration, although Eytinge has depicted five characters, his focus is the perfidious Mrs. Bardell, who is prosecuting Mr. Pickwick for breach of promise of marriage through the unscrupulous attorneys Dodson and Fogg, seen in the previous chapter and the previous illustration. to sound out Mrs. Bardell's position on the lawsuit, Pickwick despatches Sam to Mrs. Bardell's Goswell street residence in chapter 26:

It was nearly nine o'clock when he reached Goswell Street. A couple of candles were burning in the little front parlour, and a couple of caps were reflected on the window-blind. Mrs. Bardell had got company.

"Mr. Weller knocked at the door, and after a pretty long interval — occupied by the party without, in whistling a tune, and by the party within, in persuading a refractory flat candle to allow itself to be lighted — a pair of small boots pattered over the floor-cloth, and Master Bardell presented himself.

"Well, young townskip," said Sam, "how's mother?"

"She's pretty well," replied Master Bardell, "so am I."

"Well, that's a mercy," said Sam; "tell her I want to speak to her, will you, my hinfant fernomenon?"

Master Bardell, thus adjured, placed the refractory flat candle on the bottom stair, and vanished into the front parlour with his message.

The two caps, reflected on the window-blind, were the respective head-dresses of a couple of Mrs. Bardell's most particular acquaintance, who had just stepped in, to have a quiet cup of tea, and a little warm supper of a couple of sets of pettitoes and some toasted cheese. The cheese was simmering and browning away, most delightfully, in a little Dutch oven before the fire; the pettitoes were getting on deliciously in a little tin saucepan on the hob; and Mrs. Bardell and her two friends were getting on very well, also, in a little quiet conversation about and concerning all their particular friends and acquaintance; when Master Bardell came back from answering the door, and delivered the message intrusted to him by Mr. Samuel Weller.

"Mr. Pickwick's servant!" said Mrs. Bardell, turning pale.

"Bless my soul!" said Mrs. Cluppins.

"Well, I raly would not ha' believed it, unless I had ha' happened to ha' been here!" said Mrs. Sanders.

Mrs. Cluppins was a little, brisk, busy-looking woman; Mrs. Sanders was a big, fat, heavy-faced personage; and the two were the company.

Mrs. Bardell felt it proper to be agitated; and as none of the three exactly knew whether under existing circumstances, any communication, otherwise than through Dodson & Fogg, ought to be held with Mr. Pickwick's servant, they were all rather taken by surprise. In this state of indecision, obviously the first thing to be done, was to thump the boy for finding Mr. Weller at the door. So his mother thumped him, and he cried melodiously.

"Hold your noise — do — you naughty creetur!" said Mrs. Bardell.

"Yes; don't worrit your poor mother," said Mrs. Sanders.

"She's quite enough to worrit her, as it is, without you, Tommy," said Mrs. Cluppins, with sympathising resignation.

"Ah! worse luck, poor lamb!" said Mrs. Sanders. At all which moral reflections, Master Bardell howled the louder.

"Now, what shall I do?" said Mrs. Bardell to Mrs. Cluppins.

"I think you ought to see him," replied Mrs. Cluppins. "But on no account without a witness."

In the longer programs of illustration — those by Seymour and Browne (1836-37), Browne in the British Household Edition (1873), and Nast in the American Household Edition, the equivalent scene involves a more nuanced depiction of conflict and irony of situation in "The Trial" by Phiz (ch. 34) for March 1837 (plate), and "Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick" by Phiz (ch. 46) for August 1837 (plate), but neither of these presents the widow in the context of her lodgings and support, and in both Phiz is much more interested in the comic and ironic possibilities of depicting an important narrative situation. no illustrator finds the overly plump, middle-aged Mrs. Bardell an attractive or even a pleasant character, but Eytinge does not merely caricature her as Phiz does; rather, Eytinge depicts both her and her supporters as ugly, and somehow warped from the inside as they drown their supposed misfortunes in sherry.

In this respect, Phiz's 1873 woodcut is "revisionist" in that the ladies are much more fashionably dressed, and Mrs. Bardell far more elegantly coiffed in "Mrs. Bardell screamed violently; Tommy roared; Mrs. Cluppins shrunk within herself; and Mrs. Sanders made off without more ado". On the other hand, Phiz's depiction of her earlier, during the trial scene, "'An admonitory gesture from Perker restrained him, and he listened to the learned gentleman's continuation with a look of indignation,' etc." is of a beaked-and-red-nosed, obese, middle-aged woman in an excessively feathered hat, although she is not quite so repulsive in 1873 as she was in 1836 in the same scene.

And that's all I can do now friends, what started from a seizure last week (I thought so at the time), turned into a terrible headache along with terrible neck pain, but now has decided to take the rest of me along with it. And I better stop now or I'll be taking the computer and a lot of stuff around me with me when I fall.

Kim

I hope you are feeling better soon. At least the Kyd illustrations, by being absent, must make you feel better.

The illustrations of Sol Eytinge and Thomas Nast seem to be very similar. Both artists present illustrations that are reasonably simple in design and presentation. There are few incidences where any of the characters move beyond a simple portrait. The faces of the individual characters seem drawn from the same well of simplicity rather than a unique individuality. Where are the characteristics that help us identify a personality?

Their work pales in comparison to Browne’s. With Browne, we get life, movement, suggestion and emblematic detail. While Phiz’s work has deteriorated from the glory days of Dombey and Son, the illustrations still invite us to think about their meaning and context.

I hope you are feeling better soon. At least the Kyd illustrations, by being absent, must make you feel better.

The illustrations of Sol Eytinge and Thomas Nast seem to be very similar. Both artists present illustrations that are reasonably simple in design and presentation. There are few incidences where any of the characters move beyond a simple portrait. The faces of the individual characters seem drawn from the same well of simplicity rather than a unique individuality. Where are the characteristics that help us identify a personality?

Their work pales in comparison to Browne’s. With Browne, we get life, movement, suggestion and emblematic detail. While Phiz’s work has deteriorated from the glory days of Dombey and Son, the illustrations still invite us to think about their meaning and context.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "There was a boxer with a very strange name in another Dickens novel, but at the moment it eludes me which novel it was. But the name had something to do with a chicken, like “the S..."

Thanks for the reference, May Lou! You have got a point there when you mention the prevalence for cock fighting as a reason why boxers' names had something to do with chicken - although this particular bird brings forth associations of cowardice, at least in my mind.

Thanks for the reference, May Lou! You have got a point there when you mention the prevalence for cock fighting as a reason why boxers' names had something to do with chicken - although this particular bird brings forth associations of cowardice, at least in my mind.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "and here comes another brilliant name I don’t want to suppress – the Porkenhams..."

We talked last week about listening v. reading. This is a good example of what you can miss wit..."

I really loved that name - as well as that of Count Smorltalk a few chapters earlier. Re-reading this book once again is great fun for me!

We talked last week about listening v. reading. This is a good example of what you can miss wit..."

I really loved that name - as well as that of Count Smorltalk a few chapters earlier. Re-reading this book once again is great fun for me!

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Would it really have been so disastrous for Miss Witherfield’s reputation if she and Mr. Pickwick had solved the mystery of their meeting the night before? How would Mr. Magnus hav..."

Miscommunication as a theme of the novel is a very good point, Mary Lou! Miscommunication in connection with all sorts of awkward coincidences, e.g. the fact that Miss Witherfield is the same person as the lady that Mr. Peter Magnus has proposed to - a coincidence that is not so big after all, considering that PM proposed to a lady staying at the inn. But there is yet another awkward coincidence, namely that Mr. Pickwick chose so dramatic words when referring to Mr. Jingle - and yet so indefinite ones - that Peter Magnus was led to refer them to a lady, and then these two misunderstandings combined and we have a truly Pickwickian situation. There is definitely some Pickwick in Seinfeld ...

Miscommunication as a theme of the novel is a very good point, Mary Lou! Miscommunication in connection with all sorts of awkward coincidences, e.g. the fact that Miss Witherfield is the same person as the lady that Mr. Peter Magnus has proposed to - a coincidence that is not so big after all, considering that PM proposed to a lady staying at the inn. But there is yet another awkward coincidence, namely that Mr. Pickwick chose so dramatic words when referring to Mr. Jingle - and yet so indefinite ones - that Peter Magnus was led to refer them to a lady, and then these two misunderstandings combined and we have a truly Pickwickian situation. There is definitely some Pickwick in Seinfeld ...

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "In this chapter, he wears green glasses, being the green-eyed monster of jealousy that he is, but when Mr. Pickwick first meets him, we wears blue glasses. ..."

Another continuity..."

Probably just a consequence of having to write under pressure and not remembering every little detail already given. It would have been fun, though on a surreal basis, if Peter Magnus's colour glasses had always changed according to his personal mood. I don't think, however, that Victorians would have liked such a joke as being too unrealistic.

Another continuity..."

Probably just a consequence of having to write under pressure and not remembering every little detail already given. It would have been fun, though on a surreal basis, if Peter Magnus's colour glasses had always changed according to his personal mood. I don't think, however, that Victorians would have liked such a joke as being too unrealistic.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 25 is rather long, as can already guessed from the introductory title, and in it, the narrator brings the Ipswich episode to a close by showing us how Mr. Pickwick and his ..."

Your suggestion of there being love affairs among servants and other love affairs among the higher classes is very interesting. In former times, the former would have been treated as comedy, whereas the latter, if they were interesting, would have been classified as tragedy (or romance). In PP, however, event the love matters of higher-classed people are treated in a humoristic vein, and while we may feel some pity for the spinster aunt or might worry about the future of Peter Magnus and Miss Witherfield, the narrator himself focuses more, or even exclusively, on the comic potential of these misunderstandings and thwarted love affairs.

I think that a lot of the love stories we get here may have been derived by Dickens from books he read (picaresque novels) but also from plays he saw. The Witherfield-Pickwick encounter seems like a real Comedy of Errors to me.

Your suggestion of there being love affairs among servants and other love affairs among the higher classes is very interesting. In former times, the former would have been treated as comedy, whereas the latter, if they were interesting, would have been classified as tragedy (or romance). In PP, however, event the love matters of higher-classed people are treated in a humoristic vein, and while we may feel some pity for the spinster aunt or might worry about the future of Peter Magnus and Miss Witherfield, the narrator himself focuses more, or even exclusively, on the comic potential of these misunderstandings and thwarted love affairs.

I think that a lot of the love stories we get here may have been derived by Dickens from books he read (picaresque novels) but also from plays he saw. The Witherfield-Pickwick encounter seems like a real Comedy of Errors to me.