The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Pickwick Papers

>

Pickwick Papers - Chapter 3 - 5

Chapter 4

I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consider: “Many authors entertain, not only the foolish, but a really dishonest objection to acknowledge the sources from whence they derive much valuable information. We have no such feeling.” As we read through the collected novels of Dickens we will discover how much of his own life and experience colours his writing. I think the opening words of this chapter also have relevance to our discussion of how The Pickwick Papers came to be recorded. The phrase “acknowledge the sources from whence they derive much valuable information” may help us understand the meaning of the total title of this book.

Once again we learn that a debt is owed to Mr Snodgress’s note-book for preserving this chapter’s adventure. What can be more grand than a military on parade and manoeuvres, especially since even the thought of such an event sends our imaginations into overdrive as to what might happen to our intrepid Pickwickians. The ceremony is described as one of “utmost grandeur and importance.” And so, here we go! Let the parade, and its possible consequences begin.

We read of a Colonel Boulder who gallops from place to place and of other officers who “were running backwards and forwards.” Naturally, our Pickwickian friends have “stationed themselves in the front rank of the crowd.” More people come to watch the spectacle. In a short time the Pickwickians were in a situation “rather more uncomfortable than pleasing or desirable.” Perhaps a lesson for us all is never be in the front of the spectators to a parade, especially a military parade. Mr Snodgrass, in full flight as a poet, calls the event “a noble and brilliant sight ... in whose bosom a blaze of poetry was bursting forth.” And so the situation evolves. Dickens takes delight in growing the event to a fever pitch which is initially resolved when the troops fire their weapons, apparently right at Mr Pickwick. Consider how far we are removed from the tone and language of “The Stroller’s Tale” in the previous chapter.

Thoughts

Dickens is a master of creating the humourous scene, and here is an early example of one such situation. What makes this section of the chapter appealing to you?

I also enjoy how Dickens employs the technique of understatement. When I read that “Pickwick displayed that perfect coolness and self-possession, which are the indispensable accompaniments of a great mind” it was a perfect companion to the raucous events that were unfolding around him. Later, when Pickwick leaves the field of (mock) battle with haste, but not grace, due to the fact that his “figure was by no means adapted for that mode of retreat,” the image of Pickwick was clearly impressed in my mind. I am finding that Dickens is relying on physical comedy a great deal in the early chapters. Next, Pickwick, Snodgrass, and Winkle find themselves confronting part of the British army which leads to Mr Pickwick not mounting a counter attack against the British army but rather chasing his hat which was “gambolling playfully away.” What follows is a short dissertation on how to capture one’s runaway hat. While Pickwick chases his hat we are left to contemplate the efficiency of the British Army. A wonderful, visual contrast. Pickwick trying to subdue his runaway hat and the British army trying to subdue a curious audience of onlookers.

Thoughts

Why is situational comedy funny? Did you find this part of chapter 4 effective in developing both the tone of the chapter and the further establish Mr Pickwick’s character?

Mr Pickwick’s hat conveniently rolls up against a carriage that just happens to contain Mr Tupman and an acquaintance of his, a Mr Wardle. From the barouche comes a picnic lunch for all, served in fits and starts by the servant boy Joe who only skill resides in his ability to fall asleep. As well as the food on the menu there seems to be an interesting side dish of romance heating up between Mr Tupman and Miss Wardle. Mr Pickwick receives an invitation to visit Mr Wardle’s home, Manor Farm, Dingley Dell, for at least a week. And so the chapter ends, with an invitation to Dingley Dell. Something tells me more adventures await under its roof.

Thoughts

The first few chapters have introduced much of interest in The Pickwick Papers. Dickens has presented us with both somber and serious stories and events and then counterbalanced these with events with broad physical comedy and marvellous examples of understatement. What have you noticed and enjoyed so far in your reading in terms of character presentation, language usage, literary techniques, and effective use of humour?

To what degree might writing in a comedic manner be more difficult that writing with a more tragic voice?

I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consider: “Many authors entertain, not only the foolish, but a really dishonest objection to acknowledge the sources from whence they derive much valuable information. We have no such feeling.” As we read through the collected novels of Dickens we will discover how much of his own life and experience colours his writing. I think the opening words of this chapter also have relevance to our discussion of how The Pickwick Papers came to be recorded. The phrase “acknowledge the sources from whence they derive much valuable information” may help us understand the meaning of the total title of this book.

Once again we learn that a debt is owed to Mr Snodgress’s note-book for preserving this chapter’s adventure. What can be more grand than a military on parade and manoeuvres, especially since even the thought of such an event sends our imaginations into overdrive as to what might happen to our intrepid Pickwickians. The ceremony is described as one of “utmost grandeur and importance.” And so, here we go! Let the parade, and its possible consequences begin.

We read of a Colonel Boulder who gallops from place to place and of other officers who “were running backwards and forwards.” Naturally, our Pickwickian friends have “stationed themselves in the front rank of the crowd.” More people come to watch the spectacle. In a short time the Pickwickians were in a situation “rather more uncomfortable than pleasing or desirable.” Perhaps a lesson for us all is never be in the front of the spectators to a parade, especially a military parade. Mr Snodgrass, in full flight as a poet, calls the event “a noble and brilliant sight ... in whose bosom a blaze of poetry was bursting forth.” And so the situation evolves. Dickens takes delight in growing the event to a fever pitch which is initially resolved when the troops fire their weapons, apparently right at Mr Pickwick. Consider how far we are removed from the tone and language of “The Stroller’s Tale” in the previous chapter.

Thoughts

Dickens is a master of creating the humourous scene, and here is an early example of one such situation. What makes this section of the chapter appealing to you?

I also enjoy how Dickens employs the technique of understatement. When I read that “Pickwick displayed that perfect coolness and self-possession, which are the indispensable accompaniments of a great mind” it was a perfect companion to the raucous events that were unfolding around him. Later, when Pickwick leaves the field of (mock) battle with haste, but not grace, due to the fact that his “figure was by no means adapted for that mode of retreat,” the image of Pickwick was clearly impressed in my mind. I am finding that Dickens is relying on physical comedy a great deal in the early chapters. Next, Pickwick, Snodgrass, and Winkle find themselves confronting part of the British army which leads to Mr Pickwick not mounting a counter attack against the British army but rather chasing his hat which was “gambolling playfully away.” What follows is a short dissertation on how to capture one’s runaway hat. While Pickwick chases his hat we are left to contemplate the efficiency of the British Army. A wonderful, visual contrast. Pickwick trying to subdue his runaway hat and the British army trying to subdue a curious audience of onlookers.

Thoughts

Why is situational comedy funny? Did you find this part of chapter 4 effective in developing both the tone of the chapter and the further establish Mr Pickwick’s character?

Mr Pickwick’s hat conveniently rolls up against a carriage that just happens to contain Mr Tupman and an acquaintance of his, a Mr Wardle. From the barouche comes a picnic lunch for all, served in fits and starts by the servant boy Joe who only skill resides in his ability to fall asleep. As well as the food on the menu there seems to be an interesting side dish of romance heating up between Mr Tupman and Miss Wardle. Mr Pickwick receives an invitation to visit Mr Wardle’s home, Manor Farm, Dingley Dell, for at least a week. And so the chapter ends, with an invitation to Dingley Dell. Something tells me more adventures await under its roof.

Thoughts

The first few chapters have introduced much of interest in The Pickwick Papers. Dickens has presented us with both somber and serious stories and events and then counterbalanced these with events with broad physical comedy and marvellous examples of understatement. What have you noticed and enjoyed so far in your reading in terms of character presentation, language usage, literary techniques, and effective use of humour?

To what degree might writing in a comedic manner be more difficult that writing with a more tragic voice?

Chapter 5

Early in a novel I like to see if I can find any rhythm or early pattern in what I have read so far. I look at the initial characters who have been introduced, the general setting, mood and such. For The Pickwick Papers, I am enjoying the delightful characters, their innocence and their plans to set off on an excellent adventure. It is probably stretching it to see the Pickwickians as pilgrims in the same vein as we find in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Still, there are echoes of a group going on a trip and telling stories to amuse themselves. I’ve noticed how chapters open in the morning hours and end in the evening. I find the initial chapters are episodic in nature. Perhaps the strongest feeling I get is the incredible feeling of the theatrical within the novel. Characters, scenes, conversations and actions all feel theatrical to me.

Thoughts

How about you? What are your initial feelings and expectations of The Pickwick Papers?

Although it is very early in the novel, how do you think the novel will evolve as we move through it?

We might look upon this chapter as a transition chapter as Dickens needs to move the Pickwick crew to our new setting that will be Manor Farm. The chapter is one of light-hearted Pickwickian humour. The chapter begins with a beautiful morning in which our intrepid travellers enjoy the beauty of the land and the history of their location. Into this scene comes the dismal man who is decidedly philosophical with Mr Pickwick. He entertains Pickwick with this nugget of thought: “The morning of day and the morning of life are but too much alike” and follows that up with a more personal observation where he muses “God! what I would forfeit to have the days of my childhood restored, or to be able to forget them for ever!” Restored or forget them forever. Well, perhaps both are possible. One wonders if this is the dismal man’s attempt to become a new member of the Pickwick Club. He even goes so far as to produce (what else?) but a “greasy pocket-book” which he gives to Mr Pickwick.

Dickens has now set up the readers for yet another tale, but such a tale must wait, for in this chapter Dickens must get Pickwick to Manor Farm. Once I read that they were going to be their own guides, and travel by horse no less, I knew something was up in the humour department for the rest of this chapter. Let’s face it ... Pickwick, a carriage, playful horses, a group of jolly but rather inept people. Let the fun and humour begin!

And so it does. I think this is a wonderful and playful chapter. There may be stock situations for comedy that occur, but it doesn’t matter. In fact, the most predictable humour, in the hands of the right writer, actor, or character, are always fresh and unique.

Thoughts

Rather than me rambling on myself, please tell us your favourite part of this most memorable journey of the Pickwick Club to Manor House.

In what ways do you think Dickens makes this chapter so enjoyable to read?

Within this chapter did you find any suggestion that a more serious event might well be on the horizon? If so, where are such hints in this chapter, and why do you think your suggestion might be a set up of plot advancement?

The Pickwickians arrive at Manor Farm and are met by Mr Wardle and his “faithful attendant, the fat boy.” He assures the group that he will put their dishevelled selves to rights again with some cherry wine, a needle and thread, and towels and water. Ah, if only the world’s problems, bumps and bruises were so easy to remedy. The transition from their morning’s location is altered to a description of Wardle’s home which is old, sedate, and perfectly reflect its owner. And so off our jolly group goes now “washed, mended, brushed, and brandied.”

Now, what’s this? Mr Tupman lingers behind the group to “snatch a kiss from Emma” as the chapter concludes. Hmmm. Concludes? Or is something just starting to happen? Dickens is up to something with that kiss, but we will have to be patient and wait for our next instalment.

Thoughts

Do you have a favourite Pickwickian character yet? If so, who, and why?

Early in a novel I like to see if I can find any rhythm or early pattern in what I have read so far. I look at the initial characters who have been introduced, the general setting, mood and such. For The Pickwick Papers, I am enjoying the delightful characters, their innocence and their plans to set off on an excellent adventure. It is probably stretching it to see the Pickwickians as pilgrims in the same vein as we find in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Still, there are echoes of a group going on a trip and telling stories to amuse themselves. I’ve noticed how chapters open in the morning hours and end in the evening. I find the initial chapters are episodic in nature. Perhaps the strongest feeling I get is the incredible feeling of the theatrical within the novel. Characters, scenes, conversations and actions all feel theatrical to me.

Thoughts

How about you? What are your initial feelings and expectations of The Pickwick Papers?

Although it is very early in the novel, how do you think the novel will evolve as we move through it?

We might look upon this chapter as a transition chapter as Dickens needs to move the Pickwick crew to our new setting that will be Manor Farm. The chapter is one of light-hearted Pickwickian humour. The chapter begins with a beautiful morning in which our intrepid travellers enjoy the beauty of the land and the history of their location. Into this scene comes the dismal man who is decidedly philosophical with Mr Pickwick. He entertains Pickwick with this nugget of thought: “The morning of day and the morning of life are but too much alike” and follows that up with a more personal observation where he muses “God! what I would forfeit to have the days of my childhood restored, or to be able to forget them for ever!” Restored or forget them forever. Well, perhaps both are possible. One wonders if this is the dismal man’s attempt to become a new member of the Pickwick Club. He even goes so far as to produce (what else?) but a “greasy pocket-book” which he gives to Mr Pickwick.

Dickens has now set up the readers for yet another tale, but such a tale must wait, for in this chapter Dickens must get Pickwick to Manor Farm. Once I read that they were going to be their own guides, and travel by horse no less, I knew something was up in the humour department for the rest of this chapter. Let’s face it ... Pickwick, a carriage, playful horses, a group of jolly but rather inept people. Let the fun and humour begin!

And so it does. I think this is a wonderful and playful chapter. There may be stock situations for comedy that occur, but it doesn’t matter. In fact, the most predictable humour, in the hands of the right writer, actor, or character, are always fresh and unique.

Thoughts

Rather than me rambling on myself, please tell us your favourite part of this most memorable journey of the Pickwick Club to Manor House.

In what ways do you think Dickens makes this chapter so enjoyable to read?

Within this chapter did you find any suggestion that a more serious event might well be on the horizon? If so, where are such hints in this chapter, and why do you think your suggestion might be a set up of plot advancement?

The Pickwickians arrive at Manor Farm and are met by Mr Wardle and his “faithful attendant, the fat boy.” He assures the group that he will put their dishevelled selves to rights again with some cherry wine, a needle and thread, and towels and water. Ah, if only the world’s problems, bumps and bruises were so easy to remedy. The transition from their morning’s location is altered to a description of Wardle’s home which is old, sedate, and perfectly reflect its owner. And so off our jolly group goes now “washed, mended, brushed, and brandied.”

Now, what’s this? Mr Tupman lingers behind the group to “snatch a kiss from Emma” as the chapter concludes. Hmmm. Concludes? Or is something just starting to happen? Dickens is up to something with that kiss, but we will have to be patient and wait for our next instalment.

Thoughts

Do you have a favourite Pickwickian character yet? If so, who, and why?

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5...

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5...Rather than me rambling on myself, please tell us your favourite part of this most memorable journey of the Pickwick Club to Manor House. "

Peter, I just saw you posted the introduction. It will be my read for Tomorrow morning at breakfast. :-))

For the moment, I want to answer to the question about my favourite part: it is chapter 5. I almot choked with laughter when I was reading the Pickwickians' "problems" with the horses.

Milena wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 5...

Rather than me rambling on myself, please tell us your favourite part of this most memorable journey of the Pickwick Club to Manor House. "

Peter, I just saw you posted..."

Hi Milena

Welcome. Yes, our Pickwickian friends do seem to struggle a bit with horses. I confess to having been on horseback once in my life. It was once too much.

We look forward to you further comments. Enjoy breakfast. :-))

Rather than me rambling on myself, please tell us your favourite part of this most memorable journey of the Pickwick Club to Manor House. "

Peter, I just saw you posted..."

Hi Milena

Welcome. Yes, our Pickwickian friends do seem to struggle a bit with horses. I confess to having been on horseback once in my life. It was once too much.

We look forward to you further comments. Enjoy breakfast. :-))

Although I'd read Dickens in high school, I don't think I ever really recognized the wit until the first time I read about Mr. Pickwick chasing after his hat. And the reason it finally clicked, obviously, is that the situation is so relatable and universal. As they say - "It's funny because it's true." Amen! This was my first Dickens LOL moment and, as such, it will always be one of my favorites.

Although I'd read Dickens in high school, I don't think I ever really recognized the wit until the first time I read about Mr. Pickwick chasing after his hat. And the reason it finally clicked, obviously, is that the situation is so relatable and universal. As they say - "It's funny because it's true." Amen! This was my first Dickens LOL moment and, as such, it will always be one of my favorites.

Peter wrote: " I also can’t stop wondering if he didn’t enjoy how such writing ate up words and a couple of pages for his publication requirements...."

Peter wrote: " I also can’t stop wondering if he didn’t enjoy how such writing ate up words and a couple of pages for his publication requirements...."I've probably mentioned before (and my memory being what it is, will surely mention again) that I've never enjoyed these secondary tales, for lack of a better term. Because I don't see their point and I'm cynical by nature, I tend to agree with Peter's suspicion (above). I wonder if Dickens didn't have these underdeveloped stories floating around in his head, and saw their insertion into other novels as a way of both expanding his word count, and using up good, but not great, material.

Regarding the ongoing "is it a novel?" debate... I would call it episodic or observational fiction. Essays with a connecting thread. Similar books that come to mind: Mrs. Miniver and Mary Poppins, each which Hollywood improved (in my opinion) by adding an actual plot to connect the episodes and make it a true story with a beginning, middle, and end; a problem and a resolution. (Having said that, Jan Struthers' prose in Mrs. Miniver is just lovely.)

Regarding the ongoing "is it a novel?" debate... I would call it episodic or observational fiction. Essays with a connecting thread. Similar books that come to mind: Mrs. Miniver and Mary Poppins, each which Hollywood improved (in my opinion) by adding an actual plot to connect the episodes and make it a true story with a beginning, middle, and end; a problem and a resolution. (Having said that, Jan Struthers' prose in Mrs. Miniver is just lovely.)

As I reread these chapters, I wondered about the popularity of some literary characters, and what it is about them grabs the reader's attention and affection (even if it's the "love to hate" kind). For those who collect Dickens stuff, the same characters tend to pop up: Scrooge and Tiny Tim, of course; Sara Gamp; Miss Havisham; Fagin; etc. In this book, besides the illustrious Mr. Pickwick, of course, and Sam Weller (whom we will encounter later), the character who seems to have captured the public's attention is "the fat boy" - Joe. Joe's sonambulism certainly does make him "a

As I reread these chapters, I wondered about the popularity of some literary characters, and what it is about them grabs the reader's attention and affection (even if it's the "love to hate" kind). For those who collect Dickens stuff, the same characters tend to pop up: Scrooge and Tiny Tim, of course; Sara Gamp; Miss Havisham; Fagin; etc. In this book, besides the illustrious Mr. Pickwick, of course, and Sam Weller (whom we will encounter later), the character who seems to have captured the public's attention is "the fat boy" - Joe. Joe's sonambulism certainly does make him "anatural curiosity" but I wonder that, of all the quirky characters we come across, it is he whom people seemed to enjoy enough to want to collect.

Mary Lou wrote: "As I reread these chapters, I wondered about the popularity of some literary characters, and what it is about them grabs the reader's attention and affection (even if it's the "love to hate" kind)...."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes indeed, there are certain characters that people tend to adopt for various reasons in a novel. I think we have two reasons for adoption. The first reason is we like to adopt the characters who we see as having or projecting the attributes we ourselves have, or the attributes we would most like to have and emulate. For example, I like Pip from GE. Now, for the most of the book he is a rather dislikable chap, but the story is in the first person, as we often see Pip being honest in his self-reflections about his own failings as a friend, companion or even person. Pip can be honest with himself in retrospect. And then, in the end, he doesn’t get (I am a supporter of the first ending) what he wanted in his life, but he did learn what he needed in his life to make him a better person. I loved the honesty of Pip in GE. I also am attracted to Sydney Carton in TTC. From him, I hope hope that I too, if the time came, would be willing to act as he did. So Pip and Sydney are the people I would like to be.

For characters like the fat boy, or Sam Weller, or Mrs Gamp or a host of other characters, my attraction is that I have seen, or know or worked with people who are them. I appreciate and enjoy the fact that there are fat boys who sleep on the drop of a pin, or who are, like Sam, quirky but completely loyal to me, or who are just plain delightful in a bizarre way like Mrs Gamp.

Dickens knows people and writes them into life better than any other writer with the exception of Shakespeare.

Hi Mary Lou

Yes indeed, there are certain characters that people tend to adopt for various reasons in a novel. I think we have two reasons for adoption. The first reason is we like to adopt the characters who we see as having or projecting the attributes we ourselves have, or the attributes we would most like to have and emulate. For example, I like Pip from GE. Now, for the most of the book he is a rather dislikable chap, but the story is in the first person, as we often see Pip being honest in his self-reflections about his own failings as a friend, companion or even person. Pip can be honest with himself in retrospect. And then, in the end, he doesn’t get (I am a supporter of the first ending) what he wanted in his life, but he did learn what he needed in his life to make him a better person. I loved the honesty of Pip in GE. I also am attracted to Sydney Carton in TTC. From him, I hope hope that I too, if the time came, would be willing to act as he did. So Pip and Sydney are the people I would like to be.

For characters like the fat boy, or Sam Weller, or Mrs Gamp or a host of other characters, my attraction is that I have seen, or know or worked with people who are them. I appreciate and enjoy the fact that there are fat boys who sleep on the drop of a pin, or who are, like Sam, quirky but completely loyal to me, or who are just plain delightful in a bizarre way like Mrs Gamp.

Dickens knows people and writes them into life better than any other writer with the exception of Shakespeare.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 3

Peter wrote: "Chapter 3We are together again at the beginning of a new year reading the opening chapters of The Pickwick Papers. One wonders if the Curiosities will have as many adventures as the Pickwick Clu..."

Peter, I will admit, I was a bit underwhelmed with the developments in Chapter 3 overall; considering how Dickens leaves us in Chapter 2. I thought the duel scene in the previous chapter built up a potential moment for us in Chapter 3, where more would be revealed from the antics of the night before and the shenanigans from the morning...Meaning, Dr. Slammer and the Stranger would have more words with one another than they did in front of all the Pickwickians! Thank heavens for your summary about the chapter because I didn't realize until reading it, how much more this chapter discloses than I gave it credit.

For starters, the morose dark tale followed by the lighter more comedic, heated interaction; both scenes are telling as to the nature of two men, the drunk man in the tale, and Mr. Pickwick in his verbal altercation. The morose tale tells us about a drunkard father's inaction toward his family, creating a sad and dire environment for all included. However, in the next scene we have Mr. Pickwick, who burst like the sun (CH2), on the brink of a physical altercation with Dr. Slammer, due to the latter insulting the Pickwickians, creating a stressful, yet humorous (Imagining stout and short Mr. Pickwick being held back by his coat tails was adorably funny.) moment. It was a matter of honor and support of his fellow Pickwickians that Mr. Pickwick stands up for and remains loyal to his people. I thought this was great juxtaposition of a paternal sense, between the drunk father in the tale and Mr. Pickwick's natural inclination. It was a nice transition from dark to light.

The Canterbury Tales similarity, Peter...I see it now, distinctly. Here too, a line may be drawn from the teller of the tale to the tale itself; considering, Dismal Jemmy is rather morose himself...Asking Mr. Pickwick in Chapter 5, Did it ever strike you, on such a morning as this, that drowning would be happiness and peace? It adds another layer to his tale, does it not? I like the tale within a tale in "The Pickwick Papers," giving us an all encompassing view of the physical and mental state of a character, the teller of the tale. I made note of this approach while reading "Heart of Darkness," Conrad too, weaves a tale within a tale.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4 & 5

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4 & 5I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consider: “Many authors entertain, n..."

Early in a novel I like to see if I can find any rhythm or early pattern in what I have read so far. How about you?

I'm noticing the dark to light motif to a greater degree as we progress in our reading. Chapter 1 to Chapter 2, dark tales followed by lighter heated conversations, the grandeur of military men surrounding a gathering of Pickwickians, the stress of the military parade and to follow a light-hearted lunch with friends, mishaps and misfortune associated with a long journey to end with a peaceful and friendly welcoming...I think this will continue, Peter.

Chapter 2 begins, That punctual servant of all work, the sun, had just risen, and begun to strike a light on the morning. In Chapter 5, I read, Mr. Pickwick was roused from the reverie referenced below.

...rich and varied landscape, rendered more beautiful by the changing, shadows which passed swiftly across it as the thin and half-formed clouds skimmed away in the light of the morning sun.I wonder if Dickens's portrayal of Mr. Pickwick, may very well parallel the sun itself, as both tend to run synonymous with one another in these two episodes? Mr. Pickwick tends to be the light in these more serious scenes; either, in a comedic sense, or just by his light-hearted and open nature.

Peter -- yes, all readers have their favorites, but I was wondering more about what makes certain characters commercial, especially the minor ones. Why do people want a Sam Weller or fat boy toby jug, but not one based on Mr jingle or the dueling doctor, for example? I guess if I can figure that out, I could make a fortune!

Peter -- yes, all readers have their favorites, but I was wondering more about what makes certain characters commercial, especially the minor ones. Why do people want a Sam Weller or fat boy toby jug, but not one based on Mr jingle or the dueling doctor, for example? I guess if I can figure that out, I could make a fortune!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter -- yes, all readers have their favorites, but I was wondering more about what makes certain characters commercial, especially the minor ones. Why do people want a Sam Weller or fat boy toby j..."

I wonder if the character who reflects or even rejects the specific time period the reader is in determines to a degree how the audience receives them. For example, the original readers of PP loved Sam Weller, and Dickens, in response, gave the audience what they wanted. Will Sam Weller have the same effect on us in the 21C as we read the novel? That will be an interesting question to follow up.

I wonder if the character who reflects or even rejects the specific time period the reader is in determines to a degree how the audience receives them. For example, the original readers of PP loved Sam Weller, and Dickens, in response, gave the audience what they wanted. Will Sam Weller have the same effect on us in the 21C as we read the novel? That will be an interesting question to follow up.

Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 4 & 5

I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consider: “Many au..."

Hi Ami

Yes. I think Dickens’s portrayal of Pickwick may well parallel the sun. So far, our chapters open with anticipation and goodness with Pickwick ready to face the day with his upbeat spirit. And then, sometimes it appears something or someone rains on his parade.

I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consider: “Many au..."

Hi Ami

Yes. I think Dickens’s portrayal of Pickwick may well parallel the sun. So far, our chapters open with anticipation and goodness with Pickwick ready to face the day with his upbeat spirit. And then, sometimes it appears something or someone rains on his parade.

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 4 & 5

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 4 & 5I could not help but wonder if Dickens was fully aware how close to home the opening words of this chapter would come to his own writing career. Just consid..."

Yes, and he keeps bouncing right along! There’s something to be said about his evolving personality...The irony is, that Pickwick is an older man, still growing right before my eyes... Into what, I do not know, but I’m curious. He’s fresh and still a little green, so the slow progression to his maturation is enevitable, keeping in mind the size of the book... I would think? I do hope nothing too bad is in his near future.

I find it interesting (and confusing) that my copy has two chapter 3s, 3a and 3b. The first chapter 3 is part of the first installment and is very short. It is the characters leading up to the story told by the dismal man. The last line in the chapter and of the first installment for me is; The dismal man took the hint, and having mixed a glass of brandy and water, and slowly swallowed half of it, opened the roll of paper and proceeded partly to read and partly to relate, the following incident, which we find recorded on the Transactions of the club, as 'The Stroller's Tale.'

And chapter 3b begins the stroller's tale and the second installment. The note for this doesn't clear up the mystery, it says:

Chapter 3: Dickens had been contracted to produce numbers twenty-four pages in length. But he began by writing too much; by the end of Chapter 2 the first number was half a page too long. Rather than shorten it, another leaf Chapter 3 appeared, with a reminder of its position in the growing narrative as well as a title for the tale that began it, at the start of Number II (and in the first volume edition).

What I cannot understand is that if he was half a page too long by the end of Chapter 2, how could adding a leaf of Chapter 3 into it help.

And chapter 3b begins the stroller's tale and the second installment. The note for this doesn't clear up the mystery, it says:

Chapter 3: Dickens had been contracted to produce numbers twenty-four pages in length. But he began by writing too much; by the end of Chapter 2 the first number was half a page too long. Rather than shorten it, another leaf Chapter 3 appeared, with a reminder of its position in the growing narrative as well as a title for the tale that began it, at the start of Number II (and in the first volume edition).

What I cannot understand is that if he was half a page too long by the end of Chapter 2, how could adding a leaf of Chapter 3 into it help.

Kim wrote: "I find it interesting (and confusing) that my copy has two chapter 3s, 3a and 3b. The first chapter 3 is part of the first installment and is very short. It is the characters leading up to the stor..."

Kim

I’ll check in a couple of biographies as see if I can find an explanation. Candidly, I have no idea.

Kim

I’ll check in a couple of biographies as see if I can find an explanation. Candidly, I have no idea.

Hello all

I have been unable in the past day to find a succinct or very clear explanation for the publication confusion of the initial parts of PP. What is evident, as Kim has pointed out, is the fact that Dickens had not yet perfected the art of making each part (and thus the individual chapter total lengths) conform to the publication expectations of length.

Looking into Dickens’s process I found Charles Dickens by Michael Slater to be very helpful.

I have been unable in the past day to find a succinct or very clear explanation for the publication confusion of the initial parts of PP. What is evident, as Kim has pointed out, is the fact that Dickens had not yet perfected the art of making each part (and thus the individual chapter total lengths) conform to the publication expectations of length.

Looking into Dickens’s process I found Charles Dickens by Michael Slater to be very helpful.

Thanks Peter. I haven't figured it out either, but when Tristram skipped chapter 3a altogether and put it into chapter 3b, I figured out what was going on just not why. I haven't tried very hard to find out, just shrugged and kept going.

And here come the illustrations, prepare yourselves : -)

Part 2 Chapter 3

The Dying Clown

Chapter 3

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

‘At the close of one of these paroxysms, when I had with great difficulty held him down in his bed, he sank into what appeared to be a slumber. Overpowered with watching and exertion, I had closed my eyes for a few minutes, when I felt a violent clutch on my shoulder. I awoke instantly. He had raised himself up, so as to seat himself in bed—a dreadful change had come over his face, but consciousness had returned, for he evidently knew me. The child, who had been long since disturbed by his ravings, rose from its little bed, and ran towards its father, screaming with fright—the mother hastily caught it in her arms, lest he should injure it in the violence of his insanity; but, terrified by the alteration of his features, stood transfixed by the bedside. He grasped my shoulder convulsively, and, striking his breast with the other hand, made a desperate attempt to articulate. It was unavailing; he extended his arm towards them, and made another violent effort. There was a rattling noise in the throat—a glare of the eye—a short stifled groan—and he fell back—dead!’

Commentary:

Seymour's method of work was to sketch with pencil or pen the outline of his subject, and add the shadow effects by means of light washes of a greyish tint. A precision and neatness of touch characterise these "Pickwick" drawings, the most interesting of which is undoubtedly that representing Mr. Pickwick addressing the Club, a scene such as Seymour may have actually witnessed in the parlour of almost any respectable public-house in his own neighbourhood of Islington. The drawing which ranks second in point of interest is the artist's first idea for "The Dying Clown," illustrating "The Stroller's Tale." The original sketch is a slight outline study in pen-and-ink of the figures only, the facial expressions being cleverly rendered. In the Victoria edition of "The Pickwick Papers" a facsimile is given of a later and more developed version of the subject; this differs from the published etching, the alterations being the result, doubtless, of the criticism bestowed upon the drawing in the following letter addressed by Dickens to the artist,—apparently the only written communication from him to Seymour which has been preserved:—

"15 Furnival's Inn,

"Thursday Evening, April 1836.

"My dear Sir,—I had intended to write to you to say how much gratified I feel by the pains you have bestowed upon our mutual friend Mr. Pickwick, and how much the result of your labours has surpassed my expectations. I am happy to be able to congratulate you, the publishers, and myself on the success of the undertaking, which appears to have been most complete.

"I have now another reason for troubling you. It is this. I am extremely anxious about 'The Stroller's Tale,' the more especially as many literary friends, on whose judgment I place great reliance, think it will create considerable sensation. I have seen your design for an etching to accompany it. I think it extremely good, but still it is not quite my idea; and as I feel so very solicitous to have it as complete as possible, I shall feel personally obliged if you will make another drawing. It will give me great pleasure to see you, as well as the drawing, when it is completed. With this view I have asked Chapman and Hall to take a glass of grog with me on Sunday evening (the only night I am disengaged), when I hope you will be able to look in.

"The alteration I want I will endeavour to explain. I think the woman should be younger—the dismal man decidedly should, and he should be less miserable in appearance. To communicate an interest to the plate, his whole appearance should express more sympathy and solicitude; and while I represented the sick man as emaciated and dying, I would not make him too repulsive. The furniture of the room you have depicted admirably. I have ventured to make these suggestions, feeling assured that you will consider them in the spirit in which I submit them to your judgment. I shall be happy to hear from you that I may expect to see you on Sunday evening.—Dear Sir, very truly yours,

Charles Dickens."

In compliance with this wish, Seymour etched a new design for "The Stroller's Tale," which he conveyed to the author at the appointed time, this being the only occasion on which he and Dickens ever met. Whether the novelist again manifested dissatisfaction, or whether some other cause of irritation arose, is not known, but it is said that Seymour returned home after the interview in a very discontented frame of mind; he did nothing more for "Pickwick" from that time, and destroyed nearly all the correspondence relating to the subject. It has been stated that he received five pounds for each drawing, but it is positively asserted, on apparently trustworthy evidence, that the sum paid on account was only thirty-five shillings for each subject, and that the artist never relinquished the entire right which he had in the designs.

On the etching of this subject, the last executed by his hand for "Pickwick", the artist was engaged shortly before his suicide, April 20th, 1836. The drawing bears a stain, said to be his blood. (I'm glad I can't see it.)

Facsimile of the artist's last sketch as amended, with the attitude of the "Dismal Man" and the "Dying Clown", modified at Dickens's request.

The Dying Clown

Phiz

The second version, as copied by Phiz after the original by Seymour. Reproduced for facility of comparison with the original etching, showing variations introduced by Phiz in executing this, the alternative plate, for the "duplicate set."

Part 2 Chapter 3

The Dying Clown

Chapter 3

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

‘At the close of one of these paroxysms, when I had with great difficulty held him down in his bed, he sank into what appeared to be a slumber. Overpowered with watching and exertion, I had closed my eyes for a few minutes, when I felt a violent clutch on my shoulder. I awoke instantly. He had raised himself up, so as to seat himself in bed—a dreadful change had come over his face, but consciousness had returned, for he evidently knew me. The child, who had been long since disturbed by his ravings, rose from its little bed, and ran towards its father, screaming with fright—the mother hastily caught it in her arms, lest he should injure it in the violence of his insanity; but, terrified by the alteration of his features, stood transfixed by the bedside. He grasped my shoulder convulsively, and, striking his breast with the other hand, made a desperate attempt to articulate. It was unavailing; he extended his arm towards them, and made another violent effort. There was a rattling noise in the throat—a glare of the eye—a short stifled groan—and he fell back—dead!’

Commentary:

Seymour's method of work was to sketch with pencil or pen the outline of his subject, and add the shadow effects by means of light washes of a greyish tint. A precision and neatness of touch characterise these "Pickwick" drawings, the most interesting of which is undoubtedly that representing Mr. Pickwick addressing the Club, a scene such as Seymour may have actually witnessed in the parlour of almost any respectable public-house in his own neighbourhood of Islington. The drawing which ranks second in point of interest is the artist's first idea for "The Dying Clown," illustrating "The Stroller's Tale." The original sketch is a slight outline study in pen-and-ink of the figures only, the facial expressions being cleverly rendered. In the Victoria edition of "The Pickwick Papers" a facsimile is given of a later and more developed version of the subject; this differs from the published etching, the alterations being the result, doubtless, of the criticism bestowed upon the drawing in the following letter addressed by Dickens to the artist,—apparently the only written communication from him to Seymour which has been preserved:—

"15 Furnival's Inn,

"Thursday Evening, April 1836.

"My dear Sir,—I had intended to write to you to say how much gratified I feel by the pains you have bestowed upon our mutual friend Mr. Pickwick, and how much the result of your labours has surpassed my expectations. I am happy to be able to congratulate you, the publishers, and myself on the success of the undertaking, which appears to have been most complete.

"I have now another reason for troubling you. It is this. I am extremely anxious about 'The Stroller's Tale,' the more especially as many literary friends, on whose judgment I place great reliance, think it will create considerable sensation. I have seen your design for an etching to accompany it. I think it extremely good, but still it is not quite my idea; and as I feel so very solicitous to have it as complete as possible, I shall feel personally obliged if you will make another drawing. It will give me great pleasure to see you, as well as the drawing, when it is completed. With this view I have asked Chapman and Hall to take a glass of grog with me on Sunday evening (the only night I am disengaged), when I hope you will be able to look in.

"The alteration I want I will endeavour to explain. I think the woman should be younger—the dismal man decidedly should, and he should be less miserable in appearance. To communicate an interest to the plate, his whole appearance should express more sympathy and solicitude; and while I represented the sick man as emaciated and dying, I would not make him too repulsive. The furniture of the room you have depicted admirably. I have ventured to make these suggestions, feeling assured that you will consider them in the spirit in which I submit them to your judgment. I shall be happy to hear from you that I may expect to see you on Sunday evening.—Dear Sir, very truly yours,

Charles Dickens."

In compliance with this wish, Seymour etched a new design for "The Stroller's Tale," which he conveyed to the author at the appointed time, this being the only occasion on which he and Dickens ever met. Whether the novelist again manifested dissatisfaction, or whether some other cause of irritation arose, is not known, but it is said that Seymour returned home after the interview in a very discontented frame of mind; he did nothing more for "Pickwick" from that time, and destroyed nearly all the correspondence relating to the subject. It has been stated that he received five pounds for each drawing, but it is positively asserted, on apparently trustworthy evidence, that the sum paid on account was only thirty-five shillings for each subject, and that the artist never relinquished the entire right which he had in the designs.

On the etching of this subject, the last executed by his hand for "Pickwick", the artist was engaged shortly before his suicide, April 20th, 1836. The drawing bears a stain, said to be his blood. (I'm glad I can't see it.)

Facsimile of the artist's last sketch as amended, with the attitude of the "Dismal Man" and the "Dying Clown", modified at Dickens's request.

The Dying Clown

Phiz

The second version, as copied by Phiz after the original by Seymour. Reproduced for facility of comparison with the original etching, showing variations introduced by Phiz in executing this, the alternative plate, for the "duplicate set."

Mr. Pickwick in Chase of his Hat

Chapter 4

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of Seymour's original drawing

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Snodgrass and Mr. Winkle had each performed a compulsory Somerset with remarkable agility, when the first object that met the eyes of the latter as he sat on the ground, staunching with a yellow silk handkerchief the stream of life which issued from his nose, was his venerated leader at some distance off, running after his own hat, which was gamboling playfully away in perspective.

There are very few moments in a man’s existence when he experiences so much ludicrous distress, or meets with so little charitable commiseration, as when he is in pursuit of his own hat. A vast deal of coolness, and a peculiar degree of judgment, are requisite in catching a hat. A man must not be precipitate, or he runs over it; he must not rush into the opposite extreme, or he loses it altogether. The best way is to keep gently up with the object of pursuit, to be wary and cautious, to watch your opportunity well, get gradually before it, then make a rapid dive, seize it by the crown, and stick it firmly on your head; smiling pleasantly all the time, as if you thought it as good a joke as anybody else.

There was a fine gentle wind, and Mr. Pickwick’s hat rolled sportively before it. The wind puffed, and Mr. Pickwick puffed, and the hat rolled over and over as merrily as a lively porpoise in a strong tide: and on it might have rolled, far beyond Mr. Pickwick’s reach, had not its course been providentially stopped, just as that gentleman was on the point of resigning it to its fate.

Mr. Pickwick, we say, was completely exhausted, and about to give up the chase, when the hat was blown with some violence against the wheel of a carriage, which was drawn up in a line with half a dozen other vehicles on the spot to which his steps had been directed. Mr. Pickwick, perceiving his advantage, darted briskly forward, secured his property, planted it on his head, and paused to take breath. He had not been stationary half a minute, when he heard his own name eagerly pronounced by a voice, which he at once recognized as Mr. Tupman’s, and, looking upwards, he beheld a sight which filled him with surprise and pleasure.

Commentary:

From the original announcement of the Pickwick Papers:

"Seymour has devoted himself, heart and graver, to the task of illustrating the beauties of Pickwick. It was reserved to Gibbon to paint, in colors that will never fade, the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - to Hume to chronicle the strife and turmoil of the two proud Houses that divided England against herself - to Napier to pen in burning words, the History of the War in the Peninsula; - the deeds and actions of the gifted Pickwick yet remain for "Boz" and Seymour to hand down to posterity.

From the present appearance of these important documents and the probable extent of the selections from them, it is presumed that the series will be completed in about twenty numbers."

That only seemed to last through the first two installments, then we have this:

"In the account already mentioned as emanating from the Seymour family, the writer has set down; - "It is not our wish to connect that event in an invidious manner with the 'Pickwick' vexation. Seymour was greatly overworked; his energies were taxed to the utmost to supply the many works which his every-increasing popularity brought to him, and the effect of such increasing labor is well known. He had not the slightest pecuniary embarrassment; although the Portuguese and Spanish bonds in which he had invested money suffered a slight depreciation, they exhibited no alarming aspect during his lifetime. He was quite happy in his domestic affairs, very fond of his family, and naturally of a very cheerful disposition..........

Driving was a favorite diversion, and it was his custom during the summer to drive down to Datchet, near Windsor, and enjoy several days in fishing, sketching, and making excursions. He was also very partial to theatrical amusements, and seldom failed to visit the theatre when any good piece came out. Although there was not that excessive hilarity in Seymour's composition which the character of his works might seem to imply, there was a general adaptability for enjoyment, which went far to justify the opinion expressed of him after his death."

Part 2 Chapter 5

"Mr. Winkle Soothes the Refractory Steed"

Chapter 5

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of the original drawing

Text Illustrated:

"Now whether the tall horse, in the natural playfulness of his disposition, was desirous of having a little innocent recreation with Mr. Winkle, or whether it occurred to him that he could perform the journey as much to his own satisfaction without a rider as with one, are points upon which, of course, we can arrive at no definite and distinct conclusion. By whatever motives the animal was actuated, certain it is that Mr. Winkle had no sooner touched the reins, than he slipped them over his head, and darted backwards to their full length.

‘Poor fellow,’ said Mr. Winkle soothingly—‘poor fellow—good old horse.’ The ‘poor fellow’ was proof against flattery; the more Mr. Winkle tried to get nearer him, the more he sidled away; and, notwithstanding all kinds of coaxing and wheedling, there were Mr. Winkle and the horse going round and round each other for ten minutes, at the end of which time each was at precisely the same distance from the other as when they first commenced—an unsatisfactory sort of thing under any circumstances, but particularly so in a lonely road, where no assistance can be procured.

‘What am I to do?’ shouted Mr. Winkle, after the dodging had been prolonged for a considerable time. ‘What am I to do? I can’t get on him.’

‘You had better lead him till we come to a turnpike,’ replied Mr. Pickwick from the chaise.

‘But he won’t come!’ roared Mr. Winkle. ‘Do come and hold him.’

Mr. Pickwick was the very personation of kindness and humanity: he threw the reins on the horse’s back, and having descended from his seat, carefully drew the chaise into the hedge, lest anything should come along the road, and stepped back to the assistance of his distressed companion, leaving Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the vehicle."

Commentary:

When Seymour and Dickens began work, each apparently was certain he was doing so on his own terms, neither aware that the other considered himself in charge. The publishers probably assumed that whatever problems arose would iron themselves out during the long course of publication. Nevertheless, it became evident immediately that Seymour's efforts were at odds with Dickens's text, and the continuous strain proved almost as immediately fatal to the work as to the artist. In designing the Pickwick wrapper for instance, Seymour illustrated his original scheme, doubtless out of ignorance rather than spite for the modifications Dickens intended. The fishing and shooting scenes on the wrapper were in distinct contrast with the text, which never even mentioned angling and involved guns only in a humorous rather minor way. Dickens supposedly described the club Seymour wanted, but he failed to make any of its members Cockneys, and only one, Winkle, was even a sportsman, and he was only put in as a condescending concession to the artist. The text of the first number provided few outlets for Seymour's special talents, although he exploited these few. "The Sagacious Dog", for example, gave him a chance to display his skill in drawing gun-toting gamekeepers, receding wooded landscapes, and beautifully proportioned animals. If Seymour could not equal Cruikshank's urban street scenes, the older artist could never have modeled as well as Seymour the wise dog, or the horses featured in "The Pugnacious Cabman" and in "Mr. Winkle soothes the refractory steed" in the second number. Indeed, Seymour's animals and inanimate objects are more memorable than the Pickwickians themselves.

"Mr. Winkle Soothes the Refractory Steed"

Chapter 5

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of the original drawing

Text Illustrated:

"Now whether the tall horse, in the natural playfulness of his disposition, was desirous of having a little innocent recreation with Mr. Winkle, or whether it occurred to him that he could perform the journey as much to his own satisfaction without a rider as with one, are points upon which, of course, we can arrive at no definite and distinct conclusion. By whatever motives the animal was actuated, certain it is that Mr. Winkle had no sooner touched the reins, than he slipped them over his head, and darted backwards to their full length.

‘Poor fellow,’ said Mr. Winkle soothingly—‘poor fellow—good old horse.’ The ‘poor fellow’ was proof against flattery; the more Mr. Winkle tried to get nearer him, the more he sidled away; and, notwithstanding all kinds of coaxing and wheedling, there were Mr. Winkle and the horse going round and round each other for ten minutes, at the end of which time each was at precisely the same distance from the other as when they first commenced—an unsatisfactory sort of thing under any circumstances, but particularly so in a lonely road, where no assistance can be procured.

‘What am I to do?’ shouted Mr. Winkle, after the dodging had been prolonged for a considerable time. ‘What am I to do? I can’t get on him.’

‘You had better lead him till we come to a turnpike,’ replied Mr. Pickwick from the chaise.

‘But he won’t come!’ roared Mr. Winkle. ‘Do come and hold him.’

Mr. Pickwick was the very personation of kindness and humanity: he threw the reins on the horse’s back, and having descended from his seat, carefully drew the chaise into the hedge, lest anything should come along the road, and stepped back to the assistance of his distressed companion, leaving Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the vehicle."

Commentary:

When Seymour and Dickens began work, each apparently was certain he was doing so on his own terms, neither aware that the other considered himself in charge. The publishers probably assumed that whatever problems arose would iron themselves out during the long course of publication. Nevertheless, it became evident immediately that Seymour's efforts were at odds with Dickens's text, and the continuous strain proved almost as immediately fatal to the work as to the artist. In designing the Pickwick wrapper for instance, Seymour illustrated his original scheme, doubtless out of ignorance rather than spite for the modifications Dickens intended. The fishing and shooting scenes on the wrapper were in distinct contrast with the text, which never even mentioned angling and involved guns only in a humorous rather minor way. Dickens supposedly described the club Seymour wanted, but he failed to make any of its members Cockneys, and only one, Winkle, was even a sportsman, and he was only put in as a condescending concession to the artist. The text of the first number provided few outlets for Seymour's special talents, although he exploited these few. "The Sagacious Dog", for example, gave him a chance to display his skill in drawing gun-toting gamekeepers, receding wooded landscapes, and beautifully proportioned animals. If Seymour could not equal Cruikshank's urban street scenes, the older artist could never have modeled as well as Seymour the wise dog, or the horses featured in "The Pugnacious Cabman" and in "Mr. Winkle soothes the refractory steed" in the second number. Indeed, Seymour's animals and inanimate objects are more memorable than the Pickwickians themselves.

Here are two other illustrations that Seymour was working on, but never finished and went unpublished:

The Runaway Chaise

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of alternative design unpublished

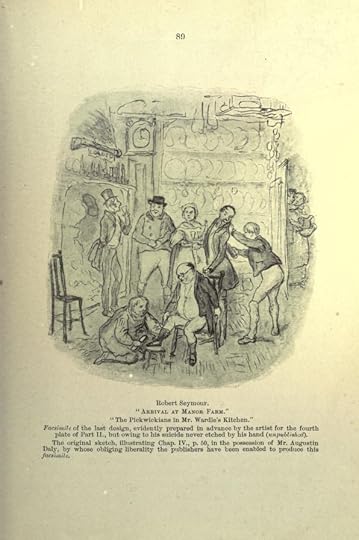

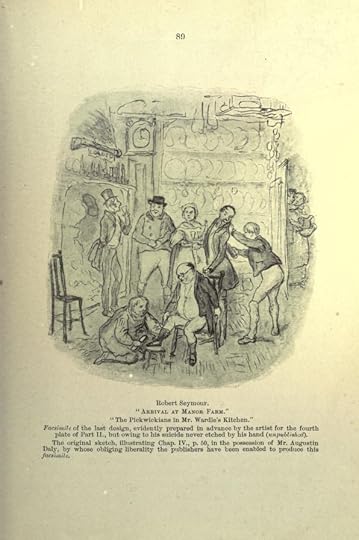

Arrival at Manor Farm

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of the last design, evidently prepared in advance by the artist for the fourth plate of Part II, but owing to his suicide never etched by his hand and went unpublished.

The Runaway Chaise

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of alternative design unpublished

Arrival at Manor Farm

Robert Seymour

Facsimile of the last design, evidently prepared in advance by the artist for the fourth plate of Part II, but owing to his suicide never etched by his hand and went unpublished.

Mr. Pickwick at the Review"

Chapter 4

Robert Buss

Commentary:

This subject was etched by R. W. Buss, and the plate submitted to "Boz" and to Chapman and Hall, the publishers, as an instance of his artistic qualifications for his proposed task, as successor to the extent of suggesting the style of his gifted predecessor. This plate illustrated Part 2, April 30th, 1836, published before the actual etching was made. Buss's experimental etching was never used in "The Pickwick Papers."

Restrain Him! Cried Mr. Snodgrass

Chapter 3

Pickwickian Illustrations

William Heath

Published 1837

Text Illustrated:

‘And allow me to say, Sir,’ said the irascible Doctor Payne, ‘that if I had been Tappleton, or if I had been Slammer, I would have pulled your nose, Sir, and the nose of every man in this company. I would, sir—every man. Payne is my name, sir—Doctor Payne of the 43rd. Good-evening, Sir.’ Having concluded this speech, and uttered the last three words in a loud key, he stalked majestically after his friend, closely followed by Doctor Slammer, who said nothing, but contented himself by withering the company with a look.

Rising rage and extreme bewilderment had swelled the noble breast of Mr. Pickwick, almost to the bursting of his waistcoat, during the delivery of the above defiance. He stood transfixed to the spot, gazing on vacancy. The closing of the door recalled him to himself. He rushed forward with fury in his looks, and fire in his eye. His hand was upon the lock of the door; in another instant it would have been on the throat of Doctor Payne of the 43rd, had not Mr. Snodgrass seized his revered leader by the coat tail, and dragged him backwards.

‘Restrain him,’ cried Mr. Snodgrass; ‘Winkle, Tupman—he must not peril his distinguished life in such a cause as this.’

‘Let me go,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Hold him tight,’ shouted Mr. Snodgrass; and by the united efforts of the whole company, Mr. Pickwick was forced into an arm-chair.

‘Leave him alone,’ said the green-coated stranger; ‘brandy-and-water—jolly old gentleman—lots of pluck—swallow this—ah!—capital stuff.’ Having previously tested the virtues of a bumper, which had been mixed by the dismal man, the stranger applied the glass to Mr. Pickwick’s mouth; and the remainder of its contents rapidly disappeared.

There was a short pause; the brandy-and-water had done its work; the amiable countenance of Mr. Pickwick was fast recovering its customary expression.

‘They are not worth your notice,’ said the dismal man.

‘You are right, sir,’ replied Mr. Pickwick, ‘they are not. I am ashamed to have been betrayed into this warmth of feeling. Draw your chair up to the table, Sir.’

"Mr. Snodgrass Seized His Revered Leader By The Coat Tail, and Dragged Him Backward."

Chapter 3

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Pictures picked from The Pickwick Papers (sounds like a tongue twister)

Chapters 3 & 4

Alfred Crowquill

Published May 1, 1837

The Review

"Everybody stood up in the carriage, and looked over somebody else's shoulder at the evolutions of the military."

Chapter 4

Thomas Sibson

Racy sketches of Expeditions from The Pickwick Club

January 1, 1836

"Never Shall I Forget The Repulsive Sight That Met my Eyes I Turned Round."

Chapter 4

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘About this time, and when he had been existing for upwards of a year no one knew how, I had a short engagement at one of the theatres on the Surrey side of the water, and here I saw this man, whom I had lost sight of for some time; for I had been travelling in the provinces, and he had been skulking in the lanes and alleys of London. I was dressed to leave the house, and was crossing the stage on my way out, when he tapped me on the shoulder. Never shall I forget the repulsive sight that met my eye when I turned round. He was dressed for the pantomimes in all the absurdity of a clown’s costume. The spectral figures in the Dance of Death, the most frightful shapes that the ablest painter ever portrayed on canvas, never presented an appearance half so ghastly. His bloated body and shrunken legs—their deformity enhanced a hundredfold by the fantastic dress—the glassy eyes, contrasting fearfully with the thick white paint with which the face was besmeared; the grotesquely-ornamented head, trembling with paralysis, and the long skinny hands, rubbed with white chalk—all gave him a hideous and unnatural appearance, of which no description could convey an adequate idea, and which, to this day, I shudder to think of. His voice was hollow and tremulous as he took me aside, and in broken words recounted a long catalogue of sickness and privations, terminating as usual with an urgent request for the loan of a trifling sum of money. I put a few shillings in his hand, and as I turned away I heard the roar of laughter which followed his first tumble on the stage.

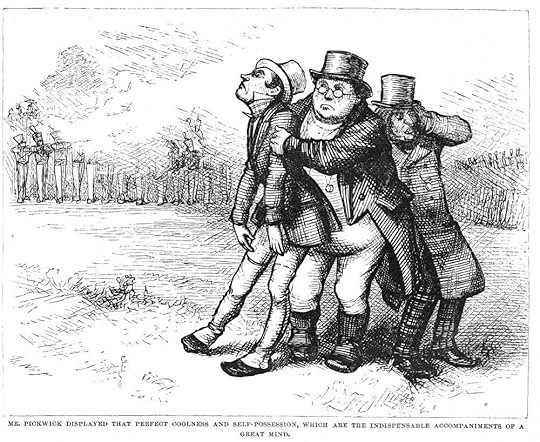

"Mr. Pickwick Displayed That Perfect Coolness and Self-possession, Which Are The Indispensable Accompaniments of a Great Mind."

Chapter 4

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘We are in a capital situation now,’ said Mr. Pickwick, looking round him. The crowd had gradually dispersed in their immediate vicinity, and they were nearly alone.

‘Capital!’ echoed both Mr. Snodgrass and Mr. Winkle.

‘What are they doing now?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick, adjusting his spectacles.

‘I—I—rather think,’ said Mr. Winkle, changing colour—‘I rather think they’re going to fire.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Mr. Pickwick hastily.

‘I—I—really think they are,’ urged Mr. Snodgrass, somewhat alarmed.

‘Impossible,’ replied Mr. Pickwick. He had hardly uttered the word, when the whole half-dozen regiments levelled their muskets as if they had but one common object, and that object the Pickwickians, and burst forth with the most awful and tremendous discharge that ever shook the earth to its centres, or an elderly gentleman off his.

It was in this trying situation, exposed to a galling fire of blank cartridges, and harassed by the operations of the military, a fresh body of whom had begun to fall in on the opposite side, that Mr. Pickwick displayed that perfect coolness and self-possession, which are the indispensable accompaniments of a great mind. He seized Mr. Winkle by the arm, and placing himself between that gentleman and Mr. Snodgrass, earnestly besought them to remember that beyond the possibility of being rendered deaf by the noise, there was no immediate danger to be apprehended from the firing.

Mr. Snodgrass and Mr. Winkle had each performed a compulsory summerset with remarkable agility

Chapter 4

Phiz

Household Edition 1874

Commentary:

In the second (May 1836) installment, acting under Dickens's directions, Robert Seymour had reluctantly depicted a scene from the pathetic "Stroller's Tale," a radical departure from the original conception of "Cockney sporting scenes" — a grim narrative about a dipsomaniacal entertainer that furnished a counterpoint to the farcical adventures of the Pickwickians. Seymour's second subject, Pickwick's pursuit of his hat in the aftermath of a military review at Rochester, Phiz reworked rather ingeniously to include the troops (rear) and Pickwick's fellow-sufferers, Snodgrass and Winkle, literally bowled over by the inexorable progress of half-a-dozen regiments:

Mr. Snodgrass and Mr. Winkle had each performed a compulsory summerset [summersault] with remarkable agility, when the first object that met the eyes of the latter as he sat on the ground staunching with a yellow silk handkerchief the stream of life which issued from his nose, was his venerated leader at some distance off, running after his own hat, which was gambolingl playfully away in perspective. [Household Edition]

Thus, Phiz improves upon the rather cluttered and decontextualized "Pickwick in chase of his hat" (May 1836) by placing the three Londoners in the foreground, the troops and their officer on horseback in the background — and eliminating the townspeople watching the military review since their presence is not germane to the physical comedy. Phiz thereby also avoids the melancholy subject of the clown's drinking himself to death, "The Stroller's Tale" of chapter 3, perhaps because it might remind even readers in the 1870s of the tragic suicide of the gifted Seymour, like the Stroller "an oversensitive artist, compelled to make a living by amusing others."

What Makes Him Go Sideways?" said Mr. Snodgrass in the Bin to Mr. Winkle

Chapter 5

Pickwickian Illustrations

William Heath

Published 1837

Text Illustrated:

‘Only his playfulness, gen’lm’n,’ said the head hostler encouragingly; ‘jist kitch hold on him, Villiam.’ The deputy restrained the animal’s impetuosity, and the principal ran to assist Mr. Winkle in mounting.

‘T’other side, sir, if you please.’

‘Blowed if the gen’lm’n worn’t a-gettin’ up on the wrong side,’ whispered a grinning post-boy to the inexpressibly gratified waiter.

Mr. Winkle, thus instructed, climbed into his saddle, with about as much difficulty as he would have experienced in getting up the side of a first-rate man-of-war.

‘All right?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick, with an inward presentiment that it was all wrong.

‘All right,’ replied Mr. Winkle faintly.

‘Let ‘em go,’ cried the hostler.—‘Hold him in, sir;’ and away went the chaise, and the saddle-horse, with Mr. Pickwick on the box of the one, and Mr. Winkle on the back of the other, to the delight and gratification of the whole inn-yard.

‘What makes him go sideways?’ said Mr. Snodgrass in the bin, to Mr. Winkle in the saddle.

‘I can’t imagine,’ replied Mr. Winkle. His horse was drifting up the street in the most mysterious manner—side first, with his head towards one side of the way, and his tail towards the other.

Mr. Pickwick had no leisure to observe either this or any other particular, the whole of his faculties being concentrated in the management of the animal attached to the chaise, who displayed various peculiarities, highly interesting to a bystander, but by no means equally amusing to any one seated behind him. Besides constantly jerking his head up, in a very unpleasant and uncomfortable manner, and tugging at the reins to an extent which rendered it a matter of great difficulty for Mr. Pickwick to hold them, he had a singular propensity for darting suddenly every now and then to the side of the road, then stopping short, and then rushing forward for some minutes, at a speed which it was wholly impossible to control.

‘What can he mean by this?’ said Mr. Snodgrass, when the horse had executed this manoeuvre for the twentieth time.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Mr. Tupman; ‘it looks very like shying, don’t it?’ Mr. Snodgrass was about to reply, when he was interrupted by a shout from Mr. Pickwick.

‘Woo!’ said that gentleman; ‘I have dropped my whip.’

‘Winkle,’ said Mr. Snodgrass, as the equestrian came trotting up on the tall horse, with his hat over his ears, and shaking all over, as if he would shake to pieces, with the violence of the exercise, ‘pick up the whip, there’s a good fellow.’ Mr. Winkle pulled at the bridle of the tall horse till he was black in the face; and having at length succeeded in stopping him, dismounted, handed the whip to Mr. Pickwick, and grasping the reins, prepared to remount."

"Bless my Soul!" Exclaimed The Agonized Mr. Pickwick, "There's the Other Horse Running Away!"

Chapter 5

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Pickwick was the very personation of kindness and humanity: he threw the reins on the horse’s back, and having descended from his seat, carefully drew the chaise into the hedge, lest anything should come along the road, and stepped back to the assistance of his distressed companion, leaving Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the vehicle.

The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing towards him with the chaise whip in his hand, than he exchanged the rotary motion in which he had previously indulged, for a retrograde movement of so very determined a character, that it at once drew Mr. Winkle, who was still at the end of the bridle, at a rather quicker rate than fast walking, in the direction from which they had just come. Mr. Pickwick ran to his assistance, but the faster Mr. Pickwick ran forward, the faster the horse ran backward. There was a great scraping of feet, and kicking up of the dust; and at last Mr. Winkle, his arms being nearly pulled out of their sockets, fairly let go his hold. The horse paused, stared, shook his head, turned round, and quietly trotted home to Rochester, leaving Mr. Winkle and Mr. Pickwick gazing on each other with countenances of blank dismay. A rattling noise at a little distance attracted their attention. They looked up.

‘Bless my soul!’ exclaimed the agonised Mr. Pickwick; ‘there’s the other horse running away!’

It was but too true. The animal was startled by the noise, and the reins were on his back. The results may be guessed. He tore off with the four-wheeled chaise behind him, and Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the four-wheeled chaise. The heat was a short one. Mr. Tupman threw himself into the hedge, Mr. Snodgrass followed his example, the horse dashed the four—wheeled chaise against a wooden bridge, separated the wheels from the body, and the bin from the perch; and finally stood stock still to gaze upon the ruin he had made.

The horse no sooner behold Mr. Pickwick advancing with the chaise whip in his hand, & c.

Chapter 5

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Pickwick was the very personation of kindness and humanity: he threw the reins on the horse’s back, and having descended from his seat, carefully drew the chaise into the hedge, lest anything should come along the road, and stepped back to the assistance of his distressed companion, leaving Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the vehicle.

The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing towards him with the chaise whip in his hand, than he exchanged the rotary motion in which he had previously indulged, for a retrograde movement of so very determined a character, that it at once drew Mr. Winkle, who was still at the end of the bridle, at a rather quicker rate than fast walking, in the direction from which they had just come. Mr. Pickwick ran to his assistance, but the faster Mr. Pickwick ran forward, the faster the horse ran backward. There was a great scraping of feet, and kicking up of the dust; and at last Mr. Winkle, his arms being nearly pulled out of their sockets, fairly let go his hold. The horse paused, stared, shook his head, turned round, and quietly trotted home to Rochester, leaving Mr. Winkle and Mr. Pickwick gazing on each other with countenances of blank dismay. A rattling noise at a little distance attracted their attention. They looked up.

‘Bless my soul!’ exclaimed the agonised Mr. Pickwick; ‘there’s the other horse running away!’

Commentary:

Compare the Nast illustration of Pickwick's difficulties with the horse rented at the Bull Inn, Rochester, to Phiz's: "'Bless my soul' exclaimed the agonized Mr. Pickwick, 'there's the other horse running away!'". Phiz has closely based his sixth 1874 illustration on Seymour's last illustration for May 1836, "Mr. Winkle Soothes the Refractory Steed"; although Phiz's horse seems more stubborn and less wild, the compositions dispose of the figures, the carriage, and the "steed" in almost exactly the same manner, the greatest discrepancy between the illustrations lying in the minimal amount of background greenery that Phiz has provided. Nast, on the other hand, has realised a later moment, when the other horse bolts, much to the dismay of the chaise's occupants, Tupman and Snodgrass, leaving Winkle and Pickwick doubly astonished. Nast convincingly directs Pickwick's gaze to the rapidly disappearing chaise, up left, while his rather more realistic and more effectively modelled Winkle (right), watches the horse that the pair have been ineffectually trying to calm. Curiously, neither artist elected to depict the subsequent scene (one attempted by Seymour, but never published), in which Snodgrass and Tupman throw themselves from the chaise and into the hedge and the vehicle crashes against the wooden bridge. Phiz, ever a good hand at a horse, has conveyed exactly the right mood for his well-proportioned animal, but one may still be impressed by Seymour's facility with horses, for the steed which Seymour convincingly depicts is far more spirited and interesting than his human adversaries.

Just an observation I had based on these few beginning chapters and the general idea I have of the book as a whole.

Just an observation I had based on these few beginning chapters and the general idea I have of the book as a whole.One reason people took to this book (as so far I have) is I think there is comfort in a story that does not have to end, that continues on into eternity despite the fact the there is a finite number of chapters. Not having to end, the idea of living on, is something people naturally take to, and thus one reason I suspect Pickwick resonates today.

I'm reminded of a poem by Philip Larkin. I paraphrase, but his description of things never-ending and endless, makes me think of Pickwick.

Kim wrote: "And here come the illustrations, prepare yourselves : -)

Part 2 Chapter 3

The Dying Clown

Chapter 3

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

‘At the close of one of these paroxysms, when I had with ..."