The Pickwick Club discussion

Sketches by Boz

>

Characters, 6 - 9

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Kim wrote: "we are waiting patiently of course, for our Christmas read."

Kim wrote: "we are waiting patiently of course, for our Christmas read."Some of us, of course, are waiting with dread. Between having to endure the discussion of yet another C story and the prospect of a root canal without anesthetic, I would have to flip a coin.

Will probably have to stop visiting PC until that nonsense is finally over for the year.

Kim doesn't give links for those of us who don't have a volume of the sketches (I think she thinks that anybody who doesn't have that shouldn't be allowed in this group, but maybe I'm wrong there). Anyhow, it's probably on line lots of places, but one of them is here:

Kim doesn't give links for those of us who don't have a volume of the sketches (I think she thinks that anybody who doesn't have that shouldn't be allowed in this group, but maybe I'm wrong there). Anyhow, it's probably on line lots of places, but one of them is here:http://charlesdickenspage.com/the_hos...

And here's a link to his general Sketches by Boz page.

http://charlesdickenspage.com/sketche...

On The Hospital Patient, except for the fact that most patients in hospitals today are sedated or on pain medication so that not many of the forms are "writhing in pain" (though some may still be), what impressed me was how contemporary this picture of city life is. (Though of course for a journalist to get admitted to a police interview would no longer be simple or even possible.)

On The Hospital Patient, except for the fact that most patients in hospitals today are sedated or on pain medication so that not many of the forms are "writhing in pain" (though some may still be), what impressed me was how contemporary this picture of city life is. (Though of course for a journalist to get admitted to a police interview would no longer be simple or even possible.)But as to the substance of the sketch:

First, there are still many homeless in many cities sick or dying in the streets or doorways, and not enough hospital beds to care for them even if they made their way to the hospital.

But more central, as an attorney who dealt in family law issues which far too often involved domestic violence, there is nothing new in the refusal of a battered spouse or girlfriend to charge her batterer with the crime, but to take on herself the responsibility for her injuries even when everybody knows the truth. The psychology of this is too deep and convoluted to explore here, but I'm fascinated (and a bit depressed) to see that it was just as strong a force nearly 200 years ago as it is today.

Thanks for the links, Everyman. I realized that the sketches were upon us already and I had not looked at my library's inventory yet. I've requested Sketches, but it's currently at another library. And the other two short stories I didn't see listed at my library, assuming they are published individually. I will have to start a hunt for those.

Thanks for the links, Everyman. I realized that the sketches were upon us already and I had not looked at my library's inventory yet. I've requested Sketches, but it's currently at another library. And the other two short stories I didn't see listed at my library, assuming they are published individually. I will have to start a hunt for those.

The Dickens page I used for The Hospital Patient didn't have The Misplaced Attachment of Mr John Dounce, but this site does:

The Dickens page I used for The Hospital Patient didn't have The Misplaced Attachment of Mr John Dounce, but this site does:http://www.classicbookshelf.com/libra...

"the Hospital Patient". My plan was to read one Sketch per day and then make a comment. Oh, my. What a depressing start.

"the Hospital Patient". My plan was to read one Sketch per day and then make a comment. Oh, my. What a depressing start.Dickens as the walker, Dickens as the watcher, Dickens as the recorder. Dickens was a man of great energy and we know he was quite the walker, often at night, but somehow it is depressing to think of him haunting about around hospitals and police stations. On the other hand, no doubt he met many characters and soaked up much of London on these rambles, so we, as readers, have ultimately benefitted.

In this sketch there is a feeling of need, a longing for some connection, but the final realization is that we are ultimately alone. We read that while there are helping hands in the hospital both for those who are alone and those in pain, there are no truly caring hands. And worse, for those on the midnight streets of London, "[w]hat are the recollections of a whole life of debasement stalk before them; when repentance seems a mockery, and sorrow comes too late [.]"

Dickens then narrows his focus to one battered woman in a hospital whose last decision on earth is to grant forgiveness to her husband who has beaten and battered her. We don't know her backstory in detail, but we do know that she has not lead a good or easy life, and in her last moments chooses to deny that Jack has beaten her. Was this her attempt to find some future salvation through the forgiveness she grants him? Dickens initially identifies her as being "of about two or three and twenty" but then consistently refers to her as a "girl." We never learn her name. Thus, she becomes an emblem for the countless women who have suffered physical abuse from the hands of their partners. In her dying moments she recounts how her father said he wished she "had died a child." To that comment, she adds, twice, "I wish I had! I wish I had!" She then dies.

The reader is left with questions. Will Jack change because of her death-bed defence of him? Will the fate of the others in the hospital room be to finally find compassion? Dickens knew the answer to these questions and so, I firmly suspect, did his readers then, as we do now.

After reading Kim's comment about men hanging about a mini-market all day I shuddered. While I'm not there yet, I do have a standing arrangement to meet a friend once a week for a coffee at a local coffee shop. We have a coffee, chat and leave all within an hour. Yet ... Is this my first step down the slippery slope of ageism?

After reading Kim's comment about men hanging about a mini-market all day I shuddered. While I'm not there yet, I do have a standing arrangement to meet a friend once a week for a coffee at a local coffee shop. We have a coffee, chat and leave all within an hour. Yet ... Is this my first step down the slippery slope of ageism?Poor Mr John Dounce. This Sketch evokes humour, pathos, and, in a minor way, tragedy. Mr Dounce is by no means heroic. He is, perhaps, more of a fool than a hero, but he does have a heroic quest.

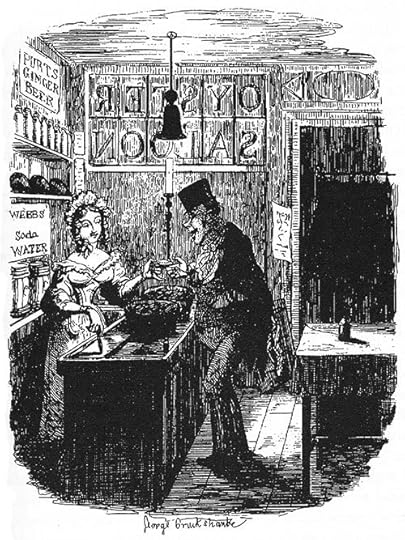

One night Mr Dounce comes across "a young lady of about five-and-twenty, all in blue". Dounce himself has a " red countenance." She is a shopgirl who sells oysters, and soon John Dounce's appetite for oysters is insatiable. Oyster-eating leads to them sitting together, and the shopgirl is soon going through some charming " serio-pantomimic fascinations" which remind him of the time he courted his wife. Dounce is soon besotted. He loses his friends, relatives and his dignity.

Earlier in the story we learn that Mr Dounce frequented the theatre. Sadly, what he does not realize is that the oyster-selling young lady, is very theatrical, and her performance was worthy of an Oscar. She takes his money, she takes his goodwill, she takes his heart and she takes his dignity. He is a Quixote without a Dulcinea.

At the age of twenty five the shopgirl was, in all likelihood, a prostitute. Dounce was had. Again, with Dickens and names, Dounce was, indeed, a dunce.

Just finished "The Hospital Patient" and was thoroughly depressed. I've only read a couple of other Sketches, so I'm not sure what's typical but, for myself, I can't imagine looking forward to getting a magazine and being smacked in the face with this awful reality. Of course, perhaps the publications they originally appeared in were more like Time or Newsweek than Ladies Home Journal.

Just finished "The Hospital Patient" and was thoroughly depressed. I've only read a couple of other Sketches, so I'm not sure what's typical but, for myself, I can't imagine looking forward to getting a magazine and being smacked in the face with this awful reality. Of course, perhaps the publications they originally appeared in were more like Time or Newsweek than Ladies Home Journal. There are so many scenes in future novels that may have come from what Dickens witnessed here, i.e. Jenny and her husband in "Bleak House" or Oliver Twist being accused of stealing and dragged in to see the magistrate. It's an interesting glimpse into why Dickens may have done so much walking, and where some of his characters and stories may have originated.

Dickens talks about the crowd witnessing the arrest, and moving on to see the questioning. Here, and further on at the hospital, he uses "we" -- I wonder if this is use of the so-called "royal we" or if, indeed, all of this was treated as a spectator sport in that time. It was, after all, a few decades before radio and television. Still - what a freak show! Can you imagine being hospitalized with fatal injuries and having the public come in and gawk at you? I'm reminded of photos I've seen from that period (but here in the US) of hangings, at which people were literally climbing trees to get a better view. Ghastly.

Mary Lou wrote: "Dickens talks about the crowd witnessing the arrest, and moving on to see the questioning. Here, and further on at the hospital, he uses "we" -- I wonder if this is use of the so-called "royal we" or if, indeed, all of this was treated as a spectator sport in that time. It was, after all, a few decades before radio and television. Still - what a freak show!"

Mary Lou wrote: "Dickens talks about the crowd witnessing the arrest, and moving on to see the questioning. Here, and further on at the hospital, he uses "we" -- I wonder if this is use of the so-called "royal we" or if, indeed, all of this was treated as a spectator sport in that time. It was, after all, a few decades before radio and television. Still - what a freak show!"I think the "we" is meant in the sense of the "editorial we", i.e. the writer tries to avoid using the first person singular for not wanting to seem to impose his views on his readers. But still, like Mary Lou, the first of these sketches had me wonder how easily the narrator obtains permission to listen to interrogations at the police station and then also to witness the meeting between the suspect and the battered woman in the hospital. Was it customary for people to obtain the authorities' permission in manners that today we would consider private? And then, was it considered in good taste to go and look at people in a hospital, or was it considered gloating.

The Sketch itself is very strong with regard to the effect created on the reader, and I think that Dickens at that point was relatively free from his penchant to drown the atmosphere in melodrama. What is described there, could still happen today, and - unluckily - often does.

I think the next two Sketches - the deplorable fate of Mr. Dounce and the downfall of the Milliner - are very similar in tone: Both can be seen as examples of mock tragedy - what happens to Mr. Dounce and to Miss Amelia is sad and unfair, and both of them are to a certain extent dupes of their own vanity. Mr. Dounce should, of course, have realized that a young woman could probably not take any genuine interest in him but had ulterior motives, and Miss Amelia might have asked herself whether those who praised her vocal cords might not do so out of politeness or interest. But although the lives of Mr. Dounce and Miss Martin take a turn for the worse, yet the tone of the narrative makes light of it, treating their personal tragedies as something to smirk about.

I think the next two Sketches - the deplorable fate of Mr. Dounce and the downfall of the Milliner - are very similar in tone: Both can be seen as examples of mock tragedy - what happens to Mr. Dounce and to Miss Amelia is sad and unfair, and both of them are to a certain extent dupes of their own vanity. Mr. Dounce should, of course, have realized that a young woman could probably not take any genuine interest in him but had ulterior motives, and Miss Amelia might have asked herself whether those who praised her vocal cords might not do so out of politeness or interest. But although the lives of Mr. Dounce and Miss Martin take a turn for the worse, yet the tone of the narrative makes light of it, treating their personal tragedies as something to smirk about.I'm quite sure that Miss Martin's business might recover, but as to Mr. Dounce, I think he is in a long-term jam. But he could have seen it coming.

Everyman wrote: "Will probably have to stop visiting PC until that nonsense is finally over for the year."

Everyman wrote: "Will probably have to stop visiting PC until that nonsense is finally over for the year."Ach, come on! That would mean you had nothing to feed your grumpiness on.

By the way, for those who don't have a printed edition of the Sketches and of the next two short stories we are going to read, and who, at the same time, happen to have an E-reader: The Delphi Collection of Charles Dickens's works is quite recommendable, and it definitely contains all these texts.

By the way, for those who don't have a printed edition of the Sketches and of the next two short stories we are going to read, and who, at the same time, happen to have an E-reader: The Delphi Collection of Charles Dickens's works is quite recommendable, and it definitely contains all these texts.

'The Hospital Patient' is a sickening story. I want to shout "No!" at the victim when she takes her husband's hand assuring him that his secret's safe with her. Justice can't be done in this way, but then again, she knows that she is dying and up until that moment she was living to die. Her father had verbally sealed her fate. It's as though he foresaw the hopelessness of her life. Evidently it must have been all that he had ever known so why should it be different for his daughter?

'The Hospital Patient' is a sickening story. I want to shout "No!" at the victim when she takes her husband's hand assuring him that his secret's safe with her. Justice can't be done in this way, but then again, she knows that she is dying and up until that moment she was living to die. Her father had verbally sealed her fate. It's as though he foresaw the hopelessness of her life. Evidently it must have been all that he had ever known so why should it be different for his daughter?This young girl seems to have resigned herself to the fact that she is losing the struggle. Perhaps she readies herself for eternity and who wants to die holding a grudge no matter how justified it is? She has now nothing to lose and the chance of having everything to gain. Surrounded by people in agonising pain mingled with her own pain she wants to escape this hell. Nowadays, no one in hospital ought

to suffer pain. Pain relief is so advanced. The truth is that despite the ideal, pain is still suffered. Nevertheless, the scale of pain of the present time bears little or no resemblance to that of Dickens's day.

That's true, Kim, that Dickens would have been a young man when he wrote the sketch about Mr Dounce. He cannot begin to envisage his older soul falling similarly for a young lady. Nor can he ever imagine that he would be one of the 'old boys'. He was 58 when he died so not old today but pretty old in Dickens's day.

That's true, Kim, that Dickens would have been a young man when he wrote the sketch about Mr Dounce. He cannot begin to envisage his older soul falling similarly for a young lady. Nor can he ever imagine that he would be one of the 'old boys'. He was 58 when he died so not old today but pretty old in Dickens's day.I feel for Mr John Dounce. His love for his previous wives does not teach him how to conduct himself successfully with this young lady. He has bitten off more than he can chew. There is no doubt that the turn that his life has taken is not great though it's not a terrible life. It's true that his new Mrs Dounce cooked for him already, but now he has added 'hen-pecked' to his daily experience. There may be no occasion to make the same mistake with a younger female again; unless, of course, he has this one carried off too! [g]

Oh poor Miss Martin! I have seen this kind of thing happen. It is cringe-able. Overzealous people in an effort to be nice are actually being kind to be cruel ...

Oh poor Miss Martin! I have seen this kind of thing happen. It is cringe-able. Overzealous people in an effort to be nice are actually being kind to be cruel ...

Hilary wrote: "That's true, Kim, that Dickens would have been a young man when he wrote the sketch about Mr Dounce. He cannot begin to envisage his older soul falling similarly for a young lady. Nor can he ever i..."

Hilary wrote: "That's true, Kim, that Dickens would have been a young man when he wrote the sketch about Mr Dounce. He cannot begin to envisage his older soul falling similarly for a young lady. Nor can he ever i..."I wonder if Dickens, in his later life, looked back at this early short story and saw himself. He left his wife for Ellen Turnan, after all. While the events are somewhat different, the story of Mr. Dounce does has some quiet shimmering similarities.

Hilary wrote: "'The Hospital Patient' is a sickening story. I want to shout "No!" at the victim when she takes her husband's hand assuring him that his secret's safe with her. Justice can't be done in this way, b..."

Hilary wrote: "'The Hospital Patient' is a sickening story. I want to shout "No!" at the victim when she takes her husband's hand assuring him that his secret's safe with her. Justice can't be done in this way, b..."I like your insight about the young wife not wanting to die holding any grudges. Surrounded by the pain and suffering in the hospital room, and more than likely guilty of some earlier transgressions herself, she may have wished for a last minute forgiveness not so much for her brutish partner but rather for her own soul.

The Mistaken Milliner

The Mistaken MillinerI know that Tristram enjoys playing the guitar, as do I. What I don't know is how to upload a music video from YouTube into Goodreads, so may I suggest anyone interested go to YouTube and search for "Mr Tanner by Harry Chapin." I was, and still am, a huge Chapin fan, and had the pleasure of seeing him perform many times. Watch the live performance that comes up in your search. I was actually at that performance. Harry was too young to die.

Miss Amelia Martin and Mr Tanner both love to sing. While their talent may be different, their critics are not. In this sketch I think Dickens asks his readers to consider a person's talent, but never forget to appreciate a person who has aspirations, dreams, or even a private, harmless joy.

Yes Peter, I wonder if Dickens saw himself mirrored in this story. I hadn't heard the name of the 'other woman' before. I do have a Dickens bio in my shelves as yet unread. I really must, as he remains firmly my favourite author.

Yes Peter, I wonder if Dickens saw himself mirrored in this story. I hadn't heard the name of the 'other woman' before. I do have a Dickens bio in my shelves as yet unread. I really must, as he remains firmly my favourite author.

Peter, I think the weight of unforgiveness would be too much to bear at life's close. I believe that it would preferably be a gracious offer of forgiveness not expecting anything in return.

Peter, I think the weight of unforgiveness would be too much to bear at life's close. I believe that it would preferably be a gracious offer of forgiveness not expecting anything in return.

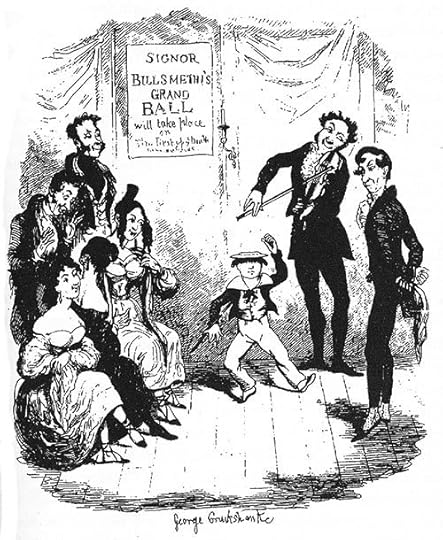

The Dancing Academy doesn't quite provide an elitist group of people to act as a ready-made social circle for Mr Augustus Cooper. The people at the top are crooks. Even the Italianate name of Signor Billsmethi is very possibly fake. It adds a little 'je ne sais quoi' to the academy. The Billsmethis are surrounded by mystique in a way that 'Bloggs' could never be!

The Dancing Academy doesn't quite provide an elitist group of people to act as a ready-made social circle for Mr Augustus Cooper. The people at the top are crooks. Even the Italianate name of Signor Billsmethi is very possibly fake. It adds a little 'je ne sais quoi' to the academy. The Billsmethis are surrounded by mystique in a way that 'Bloggs' could never be! It seems that Mr Cooper readily pays the quarterly fee, buys his dance shoes and later on at the fateful 'Ball' stands drinks for all and sundry. It does seem that Mr Cooper is flattered by the advances of Miss Billsmethi but the poor man never imagined that he would become engaged and in breach of contract all on the same night!

His mother comes to the rescue taking care of the bill. (They are BILLSmethis after all and are certainly on the make.). She is almost certainly happy to have her son back. He will never again venture beyond the fold ...

Hilary wrote: "The Dancing Academy doesn't quite provide an elitist group of people to act as a ready-made social circle for Mr Augustus Cooper. The people at the top are crooks. Even the Italianate name of Signo..."

Hilary wrote: "The Dancing Academy doesn't quite provide an elitist group of people to act as a ready-made social circle for Mr Augustus Cooper. The people at the top are crooks. Even the Italianate name of Signo..."The Dancing Academy

Hilary

Oh, I truly enjoyed your take on the last name BILLSmethi. It's always fun to look for what might be behind a Dickens character's name, or just as often, right in front of our faces.

I found this Sketch to be another one that was rather depressing. In fact, all four of our present sketches seem gloomy and pessimistic. Dickens was in his early 20's when he wrote the sketches. It seems that even from a young age, Dickens grasped the underbelly of human nature and human foibles. Love and marriage don't fare too well either.

Hilary, that's a very insightful play on words concerning Billsmethi!

Hilary, that's a very insightful play on words concerning Billsmethi!I could not help thinking of poor Mr. Pickwick when I came to the end of the last Sketch. After all, he, too, was sued for breaking an alleged marriage proposal - and, to be fair, one must say that Mrs. Bardell cannot be blamed for misinterpreting Mr. Pickwick's words, whereas in the case of the infamous dancing master and his daughter, it is quite obvious that they had been laying a trap for Mr. Cooper from the word go.

I agree with Peter: The last few Sketches were gloomy, the hospital sketch quite obviously, the others in a more indirect way. The surface of light-hearted humour that is typical of these three Sketches is a bit like the music in "The Third Man". At first, you think, That's a nice tune - but by and by, you fully realize how much it mocks the characters:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ihlku...

I agree that these sketches were depressing. While I think Dickens tried to show some humor in the latter three, he hadn't developed that skill enough yet to balance it out with the sad nature of the stories.

I agree that these sketches were depressing. While I think Dickens tried to show some humor in the latter three, he hadn't developed that skill enough yet to balance it out with the sad nature of the stories. The milliner: Poor Miss Martin would have benefited from the tough love of someone like Simon Cowell, who would have told her from the start that she had no talent and saved her a world of embarrassment down the road. I think the story would have been more interesting had Dickens focused less on her business and spent more time exploring the motives of the Rodolphs - were they being intentionally cruel or just trying not to hurt her feelings ? - and Miss Martin's feelings surrounding her humiliation. There's a certain lack of depth in this story for me.

The Dancing Academy - thank Goodness that breach of promise suits seem to be a thing of the past! It seems to have been an easy law for unscrupulous women to exploit. I got the sense that old Mrs. Cooper never let her son forget the money she had to dish out to get him free from his commitment (if, indeed, there was one - I think not). I'm reminded of Paul's grandfather in "A Hard Day's Night" - "He'll cost you a fortune in breach of promise cases!"

Mr Dounce - this one hit a bit too close to home for me. When my father - a proud, dignified man - was in his late 80s, a sweet young thing (around 70?) moved in to his retirement community. He was smitten with her and, I'm sorry to say, became a fool, flirting, buying her expensive gifts, and acting like a silly school boy. She was skilled at playing him while keeping him at arm's length. It was sad to see him become the butt of jokes among his friends and throwing his money away trying to woo the gold digger who was leading him on. So Mr. Dounce's story saddens me and makes me wonder why old men are so quick to make asses of themselves in misguided attempts to impress younger women. The same thing, I suppose, that compels older women to wear bright colored lipstick that seeps into the wrinkles around their mouths: an attempt to hold on to youth coupled with a huge dose of denial.

An aside - I've never eaten oysters. How many does one usually eat in a sitting? I got kind of nauseous just reading about Dounce downing 18 of them. Surely that's excessive, right?

Mary Lou wrote: "An aside - I've never eaten oysters. How many does one usually eat in a sitting? I got kind of nauseous just reading about Dounce downing 18 of them. Surely that's excessive, right?"

Mary Lou wrote: "An aside - I've never eaten oysters. How many does one usually eat in a sitting? I got kind of nauseous just reading about Dounce downing 18 of them. Surely that's excessive, right?"I used to eat oysters when in France. They were regarded as a delicacy but, to be quite honest, they did not impress me very much. In fact, they did not have any taste at all, it was just a kind of tasteless jelly that you sip from out of its shell. There would be five or six oysters on everybody's plate, these oysters being for starters. Nothing to write home about all in all.

Making a fool of oneself over a woman is probably something that comes with the midlife-crisis. I must confess that I have noticed signs of my midlife-crisis, e.g. asking myself what I have achieved in life up to now, why I have still not written the novel to end all novels and something like that. Luckily, I never crane my neck more than every y-chromosome compels its owner to look at younger women (because I have the best wife you could possibly find). Although I would say in my usual sarcastic way, and to banter my wife, that "A woman is as old as she looks, whereas a man is as old as the woman at his side looks." Saying that to my wife keeps me young - because I always have to run for cover afterwards, which keeps me fit.

Oh you boys!! :-)

Oh you boys!! :-)Mary-Lou, unlike Tristram, I'm afraid, I really love oysters. I have had them rarely: only twice or thrice. My first tasting was, I believe, in Portugal.' It was a rooftop restaurant beside a castle. (Or maybe I dreamed that!:D). Our friends decided that we had to taste oysters. So we had champagne (champagne or Guinness seem to be

'the thing'). We gulped rather than sipped the

oysters. (Tristram is more refined!). It tasted of the sea. Yes indeed it was probably sea water we were tasting but we thought it was

delectable. Another time was in Galway and, of course, Irish oysters are the best!:p

The next few weeks we will be reading some Sketches and also some short stories by Dickens, we are waiting patiently of course, for our Christmas read which will be here and gone before we know it. At least before I know it., from October until January time flies by for me with every moment taken up by one thing or another, so I better get started I want to get back to my dining room village some time today. :-)

This week begins with the 6th sketch in the characters section and is titled "The Hospital Patient" and was first published in the Carlton Chronicle on August 6, 1836. It begins with Dickens walking the streets of London after evening has set in. He seems to do that quite often and I wonder if he was ever afraid of being out in the city streets after dark. It seems like most people are these days, those near a city at least. But afraid or not Dickens did spend much of his time walking the London streets and in this sketch we find him pausing beneath the window of a hospital and telling us this about his thoughts while he is there:

"The sudden moving of a taper as its feeble ray shoots from window to window, until its light gradually disappears, as if it were carried farther back into the room to the bedside of some suffering patient, is enough to awaken a whole crowd of reflections; the mere glimmering of the low-burning lamps, which, when all other habitations are wrapped in darkness and slumber, denote the chamber where so many forms are writhing with pain, or wasting with disease, is sufficient to check the most boisterous merriment."

After this very depressing thought, he tells us of one of his walks when he happens to come across a crowd of people taking a pick-pocket to the police station and going along finds a powerful, ill-looking fellow, who was undergoing an examination, of having on the previous night, ill-treated a woman, with whom he lived. Several of their neighbors were there to testify to these acts of brutality; and a certificate was read from the surgeon of a neighboring hospital, describing the nature of the injuries the woman had received, and also saying that her recovery was extremely doubtful. They now, with Dickens in tow, go to the hospital where they find the woman near death, but even now she refuses to testify again her husband, or whoever he is, Dickens can say her words better than I can, especially since I can't imagine saying them at all:

'Jack,' murmured the girl, laying her hand upon his arm, 'they shall not persuade me to swear your life away. He didn't do it, gentlemen. He never hurt me.' She grasped his arm tightly, and added, in a broken whisper, 'I hope God Almighty will forgive me all the wrong I have done, and the life I have led. God bless you, Jack. Some kind gentleman take my love to my poor old father. Five years ago, he said he wished I had died a child. Oh, I wish I had! I wish I had!'

Our next sketch, hopefully more cheerful than the last is titled "Misplaced Attachment of Mr. John Dounce". It was originally titled"Love and Oysters" when published in Bell's Life in London on October 25, 1835. In this sketch we have Mr. John Dounce one of a fine collection of "old boys" to be seen at Offley's every night from half past eight until half past eleven. This brought to mind the "old boys" we must have here in our own town for out on the corner in the "mini-market" is a little section with a few tables and chairs, that way you can stop for a cup of coffee, a sandwich, whatever you want, and sit down and eat (or drink) right there. This has been taken over by "old boys" however, since there are the same set of men in the mini-market from the time it opens in the morning - 8 a.m. until evening when they all go home for supper, at least I think that's where they go. I have been amazed at this for years, to think of spending hours and hours every day of the year in a little market that is there mainly to buy gas for your car. However, reading this sketch, I guess that simply makes them "old boys".

Anyway, John Dounce has been in the same place with the same men for twenty years when one night returning home he happens to notice a newly-opened oyster-shop with a pretty young lady, there to serve the oysters and whatever other food or drink may be there. Mr. Dounce is in love and from that time on it is to the oyster shop and the young lady he goes in the evenings cutting his old friends from his life. This entire story had me thinking of Dickens and the young woman he fell in love with later in his life, although at the time of writing this he was still a very young man. Poor Mr. Dounce ends up with no young lady, no friends, and only a cook to spend his life with.

The next sketch is titled The Mistaken Milliner and we find Miss Amelia Martin and pale, tallish, thin, and two-and-thirty woman. She was a milliner and dress maker of course, and lived on her business and not above it Dickens tells us. Her life seems to be going along just fine, making dresses for young ladies, talking, gossiping, when one day she is invited to a wedding of a friend. After the dinner they are entertained with music and singing. Miss Martin is encouraged to sing, I suppose they either encouraged her to be nice, or because they have never heard her sing, for Miss Martin:

"commenced a species of treble chirruping containing constant allusions to some young gentleman of the name of Hen-e-ry, with an occasional reference to madness and damaged hearts." Of course her singing is declared to be "Beautiful", "Charming", and "Brilliant", which encourages her to continue singing, for Dickens tells us:

"Dismal wailings were heard to issue from the second-floor front, of number forty-seven, Drummond-street, George-street, Euston-square; it was Miss Martin practising."

Finally a benefit night is held and Miss Martin is one of the performers, unfortunately when her turn arrives this is the result:

The symphony began, and afterwards followed by a faint kind of ventriloquial chirpping, proceeding apparently from the deepest recesses of the interior of Miss Amelia Martin"

And our poor Miss Martin is taken off the stage with much less ceremony than she had entered it, never to sing again, at least not in public.

The last sketch for this installment is titled "The Dancing Academy" and I was thinking of Bleak House the entire time I was reading it. It was first published in Bell's Life in London in October 1835. Just like Bleak House, it was not an expensive academy, the number of pupils were limited to seventy-five, there was public tuition and private tuition, quite the place according to the advertisement Augustus Cooper saw while walking down Holborn-hill. Mr. Cooper lives in the little back parlour behind his business, cooped up on week-days, and at Bethel Chapel on Sundays. Seeing nothing of the world than that Mr. Cooper decides to join the dancing academy, which ends up to be quite an amusing little place. There he meets Signor Billsmethi, the owner of the dancing academy, and his daughter who happens to enters the room just then. Signor Billsmethi is telling him about their very popular academy, at least he says it is, why after all he is lucky to get a space at all, seeing they only have one vacancy. Unfortunately for Mr. Cooper the dance academy doesn't work out so well for him, at the end of his learning every dance step there is, he finds himself sued because because he has made promises of marriage to Signor's daughter and had now basely deserted her. The entire thing ends up with a lawyer's letter coming saying there would be an action against him, and his mother she paying twenty pounds to settle with the Signor, And poor Mr. Cooper? He....

"went back and lived with his mother, and there he lives to this day; and as he has lost his ambition for society, and never goes into the world, he will never see this account of himself and will never be any the wiser."