The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Unreasonable Men

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

THE DISCUSSION IS OPEN - WEEK SIX - PRESIDENTIAL SERIES: UNREASONABLE MEN - May 16th - May 22nd - Chapter Six- The Smile - (pages 123 - 142) - No Spoilers, please

message 51:

by

Simonetta

(last edited May 21, 2016 09:39PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

May 21, 2016 09:24PM

I looked up Taft and golfing. According to this article, he was the first US president to take up golf, was criticized for it, but in the end contributed to the popularity of the sport. I don't think all that sport did much to keep his weight down, since he was so big that he got stuck in his bathtub! http://millercenter.org/president/bio...

I looked up Taft and golfing. According to this article, he was the first US president to take up golf, was criticized for it, but in the end contributed to the popularity of the sport. I don't think all that sport did much to keep his weight down, since he was so big that he got stuck in his bathtub! http://millercenter.org/president/bio...

reply

|

flag

message 52:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 10:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

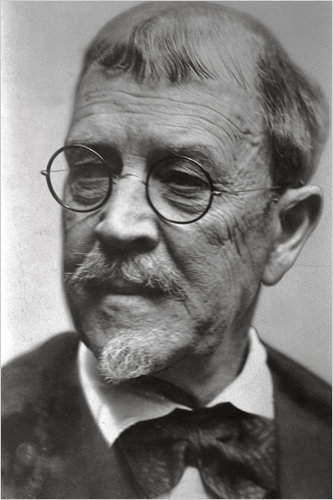

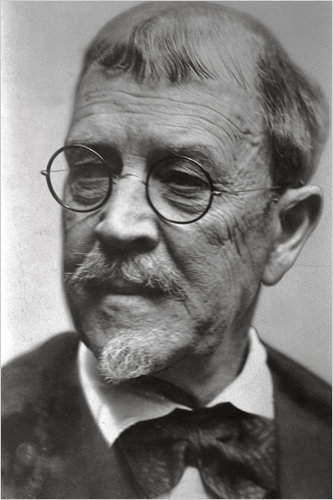

Some Senator Nelson W. Aldridge photos and portraits:

1902

1905 - 1915

The Big Four - Senators Orville Platt, John Spooner, William Allison, and Nelson Aldrich, meet informally at Aldrich’s Newport, Rhode Island, estate in 1903

SENATOR NELSON WILMARTH ALDRICH

1841-1915; Republican, Rhode Island

In 1866, a young Rhode Island grocery clerk named Nelson Aldrich confided his life’s ambition in a letter to his fiancé. “Willingly or forcibly wrested from a selfish world,” he vowed, “Success (counted as the mass counts it by dollars and cents) shall be mine.”

A career in the grocery trade would have been the easiest path to wealth, but business bored Aldrich. He chose politics instead. Though he was a poor public speaker and an indifferent campaigner, he proved adept at backroom dealing. Recognizing his potential, the boss of the state’s Republican machine promoted him up the party hierarchy and engineered his Senate election in 1880.

In the Senate Finance Committee, Aldrich pulled strings for industrialists like H. O. Havermeyer, president of the Sugar Trust, and J. Pierpont Morgan, America’s foremost investment banker. In return, the businessmen backed Aldrich’s investment schemes. He became a multimillionaire and built the finest mansion in Rhode Island. His daughter marred John D. Rockefeller Jr., son of the richest man in the world.

Wealth was not Aldrich’s only ambition. In the 1890s, he and three allies seized control of the Senate’s major committees. With Aldrich acting as ringleader, the “Big Four” senators ruled Congress for a decade. Journalists dubbed him “Boss of the Senate” and “General Manager of the United States.” Even President Theodore Roosevelt, aware that he could pass no legislation without the Big Four, deferred to Aldrich.

But times were changing. Voters resented extreme wealth inequality and corporate political power. Roosevelt, in his second term, vowed to pass reform legislation that Aldrich had suppressed or diluted. In the west, a progressive Republican insurgency led by Senator Bob La Follette of Wisconsin campaigned against Aldrich's conservative establishment.

When Roosevelt’s successor, President William Taft, fell under Aldrich’s spell, public fury exploded, and the Republican Party erupted in civil war. The ensuing conflict permanently realigned American politics and established some of the country’s most important and controversial institutions, including corporate taxes, income taxes, and the Federal Reserve—all of which were unintentionally fathered by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island.

Source: All the above from Michael Wolraith's site

1902

1905 - 1915

The Big Four - Senators Orville Platt, John Spooner, William Allison, and Nelson Aldrich, meet informally at Aldrich’s Newport, Rhode Island, estate in 1903

SENATOR NELSON WILMARTH ALDRICH

1841-1915; Republican, Rhode Island

In 1866, a young Rhode Island grocery clerk named Nelson Aldrich confided his life’s ambition in a letter to his fiancé. “Willingly or forcibly wrested from a selfish world,” he vowed, “Success (counted as the mass counts it by dollars and cents) shall be mine.”

A career in the grocery trade would have been the easiest path to wealth, but business bored Aldrich. He chose politics instead. Though he was a poor public speaker and an indifferent campaigner, he proved adept at backroom dealing. Recognizing his potential, the boss of the state’s Republican machine promoted him up the party hierarchy and engineered his Senate election in 1880.

In the Senate Finance Committee, Aldrich pulled strings for industrialists like H. O. Havermeyer, president of the Sugar Trust, and J. Pierpont Morgan, America’s foremost investment banker. In return, the businessmen backed Aldrich’s investment schemes. He became a multimillionaire and built the finest mansion in Rhode Island. His daughter marred John D. Rockefeller Jr., son of the richest man in the world.

Wealth was not Aldrich’s only ambition. In the 1890s, he and three allies seized control of the Senate’s major committees. With Aldrich acting as ringleader, the “Big Four” senators ruled Congress for a decade. Journalists dubbed him “Boss of the Senate” and “General Manager of the United States.” Even President Theodore Roosevelt, aware that he could pass no legislation without the Big Four, deferred to Aldrich.

But times were changing. Voters resented extreme wealth inequality and corporate political power. Roosevelt, in his second term, vowed to pass reform legislation that Aldrich had suppressed or diluted. In the west, a progressive Republican insurgency led by Senator Bob La Follette of Wisconsin campaigned against Aldrich's conservative establishment.

When Roosevelt’s successor, President William Taft, fell under Aldrich’s spell, public fury exploded, and the Republican Party erupted in civil war. The ensuing conflict permanently realigned American politics and established some of the country’s most important and controversial institutions, including corporate taxes, income taxes, and the Federal Reserve—all of which were unintentionally fathered by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island.

Source: All the above from Michael Wolraith's site

message 53:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 08:23PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Transformations:

In this chapter I was struck by the number of men who were being transformed from one set of personality traits or beliefs to another.

Let us begin at the beginning of the chapter with Lincoln Steffens just as an example:

"By the age of 42, Lincoln Steffens had reached the pinnacle of his career. Wealthy and famous, he lived with his wife in a beautiful farmhouse on the Connecticut shore. He and his colleagues Ray Standard Bank and Ida Tarbell had launched their own monthly, The American Magazine, which gave him freedom to write about what he wanted.

Despite his success, a sense of unease gnawed at him. "I simply don't know where I'm at," he confided to his sister. "I know things are all wrong somehow; and fundamentally; but I don't know what the matter is and I don't know what to do." Muckraking had lost its appear; exposing a few corrupt officials would not fix The System. He compared his exposes to a vigilante mob that lynches individual wrongdoers while doing nothing to improve the conditions that produced them. " I hate this hate and this hunt," he wrote. " I have bayed my bay in it, and I am sick of it."

Restless and lost, Steffens cast about for answers to society's fundamental problems. "I'm listening to all but the ignorant," he explained to his sister. "I'm playing a long, patient game, but before I die, I believe I can help to bring about an essential change in the American mind." He began his quest with an article titled "What the Matter Is in America and What to Do About It," which posed the question to three leaders he respected - Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft and Robert LaFollette."

Lincoln Steffens - 1920

More:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/boo...

by Peter Hartshorn (no photo)

by Peter Hartshorn (no photo)

Here is the article:

https://books.google.com/books?id=9U9...

Topics for Discussion:

a) Let us start with Lincoln Steffens - how had he transformed or how had he changed during this chapter?

b) What was happening to Theodore Roosevelt and how were his beliefs being tested? How was he a different man by the end of this chapter?

c) Then we have Taft - the reluctant politician - what transformations took place in him and in his life by the end of the chapter?

d) La Follette - had he changed the way he did business and was it that difficult for him to even endorse Taft - to go along with the party? What was changing him?

e) Aldridge - what factors were in play that seemed to be changing Nelson? How had he transformed from the beginning of this chapter to even end up shocking Paul Warburg? What motivated him?

f) William Jennings Bryan - once a staunch supporter of race equality and other progressive ideas seemed to modify his beliefs to satisfy the South - why did he do that and what was his transformation?

g) Read the article that Lincoln Steffens wrote (it is above)- what are your reactions - what are your ideas - what is your opinion - what do you agree and/or disagree with?

In this chapter I was struck by the number of men who were being transformed from one set of personality traits or beliefs to another.

Let us begin at the beginning of the chapter with Lincoln Steffens just as an example:

"By the age of 42, Lincoln Steffens had reached the pinnacle of his career. Wealthy and famous, he lived with his wife in a beautiful farmhouse on the Connecticut shore. He and his colleagues Ray Standard Bank and Ida Tarbell had launched their own monthly, The American Magazine, which gave him freedom to write about what he wanted.

Despite his success, a sense of unease gnawed at him. "I simply don't know where I'm at," he confided to his sister. "I know things are all wrong somehow; and fundamentally; but I don't know what the matter is and I don't know what to do." Muckraking had lost its appear; exposing a few corrupt officials would not fix The System. He compared his exposes to a vigilante mob that lynches individual wrongdoers while doing nothing to improve the conditions that produced them. " I hate this hate and this hunt," he wrote. " I have bayed my bay in it, and I am sick of it."

Restless and lost, Steffens cast about for answers to society's fundamental problems. "I'm listening to all but the ignorant," he explained to his sister. "I'm playing a long, patient game, but before I die, I believe I can help to bring about an essential change in the American mind." He began his quest with an article titled "What the Matter Is in America and What to Do About It," which posed the question to three leaders he respected - Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft and Robert LaFollette."

Lincoln Steffens - 1920

More:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/boo...

by Peter Hartshorn (no photo)

by Peter Hartshorn (no photo)Here is the article:

https://books.google.com/books?id=9U9...

Topics for Discussion:

a) Let us start with Lincoln Steffens - how had he transformed or how had he changed during this chapter?

b) What was happening to Theodore Roosevelt and how were his beliefs being tested? How was he a different man by the end of this chapter?

c) Then we have Taft - the reluctant politician - what transformations took place in him and in his life by the end of the chapter?

d) La Follette - had he changed the way he did business and was it that difficult for him to even endorse Taft - to go along with the party? What was changing him?

e) Aldridge - what factors were in play that seemed to be changing Nelson? How had he transformed from the beginning of this chapter to even end up shocking Paul Warburg? What motivated him?

f) William Jennings Bryan - once a staunch supporter of race equality and other progressive ideas seemed to modify his beliefs to satisfy the South - why did he do that and what was his transformation?

g) Read the article that Lincoln Steffens wrote (it is above)- what are your reactions - what are your ideas - what is your opinion - what do you agree and/or disagree with?

I agree, Bentley, that Taft used TR to get what he wanted, and I agree with your parallel to Wilson's wife.

I agree, Bentley, that Taft used TR to get what he wanted, and I agree with your parallel to Wilson's wife.Taft was never as forthcoming about his platform as TR was. Like many politicians, he tended to keep his cards closer to his chest.

As others have mentioned, I enjoyed learning more about Taft as a politician and a President. Historically, he is a somewhat forgotten president. Sandwiched between an iconic Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, the WW1 president. Sadly, popular history seems to only remember that he was an obese man who got stuck in a bathtub.

As others have mentioned, I enjoyed learning more about Taft as a politician and a President. Historically, he is a somewhat forgotten president. Sandwiched between an iconic Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, the WW1 president. Sadly, popular history seems to only remember that he was an obese man who got stuck in a bathtub.

message 57:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 10:25AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Topic for Discussion:

Lincoln Steffens in The Shame of he Cities articles thinks that America should look in the mirror, What do you think of what he says? - and is it as relevant in Theodore Roosevelt's day as it is now?

In reading about Theodore Roosevelt in this book - what do you think about what he said about TR for example?

Also was Theodore Roosevelt right when he told Steffens that he was getting into dangerous territory? Why or why not?

Lincoln Steffens, The Shame of the Cities

Annotation

In the 1890s, changes in printing technology made possible inexpensive magazines that could appeal to a broader and increasingly more literate middle-class audience. Given the reform impulses popular in the early 20th century, many of these magazines featured reform-oriented investigative reporting that became known as "muckraking" (so named by President Theodore Roosevelt after the muckrake in Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress who could "look no way but downward, with a muckrake in his hands").

In October 1902 McClure's Magazine published what many consider the first muckraking article, Lincoln Steffens' "Tweed Days in St. Louis." The "muckrakers" wrote on many subjects, such as child labor, prisons, religion, corporations, and insurance companies. But urban political corruption remained a particularly popular target, and in 1904 Steffens collected and published his writings on St. Louis, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York as The Shame of the Cities. The Introduction, below, suggested his overall conclusions about political corruption.

Lincoln Steffens wrote: "Because politics is business. That's what's the matter with it. That's what's the matter with everything—art, literature, religion, journalism, law, medicine—they're all business, and all—as you see them.

Make politics a sport, as they do in England, or a profession, as they do in Germany, and we'll have—well, something else than we have now, if we want it, which is another question. But don't try to reform politics with the banker, the lawyer, and the dry-goods merchant, for these are business men and there are two great hindrances to their achievement of reform: one is that they are different from, but no better than, the politicians; the other is that politics is not "their line." There are exceptions both ways. Many politicians have gone out into business and done well (Tammany ex-mayors, and nearly all the old bosses of Philadelphia are prominent financiers in their cities), and business men have gone into politics and done well (Mark Hanna, for example). They haven't reformed their adopted trades, however, though they have sometimes sharpened them most pointedly. The politician is a business man with a specialty. When a business man of some other line learns the business of politics, he is a politician, and there is not much reform left in him. Consider the United States Senate, and believe me.

The commercial spirit is the spirit of profit, not patriotism; of credit, not honor; of individual gain, not national prosperity; of trade and dickering, not principle. "My business is sacred," says the business man in his heart. "Whatever prospers my business, is good; it must be. Whatever hinders it, is wrong; it must be. A bribe is bad, that is, it is a bad thing to take; but it is not so bad to give one, not if it is necessary to my business." "Business is business" is not a political sentiment, but our politician has caught it. He takes essentially the same view of the bribe, only he saves his self-respect by piling all his contempt upon the bribe-giver, and he has the great advantage of candor. "It is wrong, maybe," he says, "but if a rich merchant can afford to do business with me for the sake of a convenience or to increase his already great wealth, I can afford, for the sake of a living, to meet him half way. I make no pretensions to virtue, not even on Sunday." And as for giving bad government or good, how about the merchant who gives bad goods or good goods, according to the demand?

But there is hope, not alone despair, in the commercialism of our politics. If our political leaders are to be always a lot of political merchants, they will supply any demand we may create. All we have to do is to establish a steady demand for good government. The bosses have us split up into parties. To him parties are nothing but means to his corrupt ends. He "bolts" his party, but we must not; the bribe-giver changes his party, from one election to another, from one county to another, from one city to another, but the honest voter must not. Why? Because if the honest voter cared no more for his party than the politician and the grafter, then the honest vote would govern, and that would be bad—for graft. It is idiotic, this devotion to a machine that is used to take our sovereignty from us. If we would leave parties to the politicians, and would vote not for the party, not even for men, but for the city, and the State, and the nation, we should rule parties, and cities, and States, and nation. If we would vote in mass on the more promising ticket, or, if the two are equally bad, would throw out the party that is in, and wait till the next election and then throw out the other party that is in— I say, the commercial politician would feel a demand for good government and he would supply it. That process would take a generation or more to complete, for the politicians now really do not know what good government is. But it has taken as long to develop bad government, and the politicians know what that is. If it would not "go," they would offer something else, and, if the demand were steady, they, being so commercial, would "deliver the goods."

But do the people want good government? Tammany says they don't. Are the people honest? Are the people better than Tammany? Are they better than the merchant and the politician? Isn't our corrupt government, after all, representative?

President Roosevelt has been sneered at for going about the country preaching, as a cure for our American evils, good conduct in the individual, simple honesty, courage, and efficiency. "Platitudes" the sophisticated say. Platitudes? If my observations have been true, the literal adoption of Mr. Roosevelt's reform scheme would result in a revolution, more radical and terrible to existing institutions, from the Congress to the Church, from the bank to the ward organization, than socialism or even than anarchy. Why, that would change all of us—not alone our neighbors, not alone the grafters, but you and me.

No, the contemned methods of our despised politics are the master methods of our braggart business, and the corruption that shocks us in public affairs we practice ourselves in our private concerns. There is no essential difference between the pull that gets your wife into society or for your book a favorable review, and that which gets a heeler into office, a thief out of jail, and a rich man's son on the board of directors of a corporation; none between the corruption of a labor union, a bank, and a political machine; none between a dummy director of a trust and the caucus-bound member of a legislature; none between a labor boss like Sam Parks, a boss of banks like John D. Rockefeller, a boss of railroads like J. P. Morgan, and a political boss like Matthew S. Quay. The boss is not a political, he is an American institution, the product of a freed people that have not the spirit to be free.

And it's all a moral weakness; a weakness right where we think we are strongest. Oh, we are good—on Sunday, and we are "fearfully patriotic" on the Fourth of July. But the bribe we pay to the janitor to prefer our interests to the landlord's, is the little brother of the bribe passed to the alderman to sell a city street, and the father of the air-brake stock assigned to the president of a railroad to have this life-saving invention adopted on his road. And as for graft, railroad passes, saloon and bawdy-house blackmail, and watered stock, all these belong to the same family. We are pathetically proud of our democratic institutions and our republican form of government, of our grand Constitution and our just laws. We are a free and sovereign people, we govern ourselves and the government is ours. But that is the point. We are responsible, not our leaders, since we follow them. We let them divert our loyalty from the United States to some "party"; we let them boss the party and turn our municipal democracies into autocracies and our republican nation into a plutocracy. We cheat our government and we let our leaders loot it, and we let them wheedle and bribe our sovereignty from us. True, they pass for us strict laws, but we are content to let them pass also bad laws, giving away public property in exchange; and our good, and often impossible, laws we allow to be used for oppression and blackmail. And what can we say? We break our own laws and rob our own government, the lady at the customhouse, the lyncher with his rope, and the captain of industry with his bribe and his rebate.

The spirit of graft and of lawlessness is the American spirit.

Source: Curators of the National Museum of American History

More: What George Washington Plunkitt had to say about the Shame of the Cities articles:

http://objectofhistory.org/objects/br...

Source: Thomas Nast, "Stop Thief!" Harper's Weekly, 1871

Detail on the above:

Thomas Nast's renowned illustrations in Harper's Weekly worked to expose the political corruption of the infamous machine run beginning in the 1860s by William "Boss" Tweed in New York City's Tammany Hall. Known for their corrupt dealings, the Democratic political machine used bribes, kickbacks, patronage, and sometimes engaged in voting fraud. At the same time, they often won immigrant support because they provided badly needed services to poor communities. Because Tammany Hall controlled voting, taxes, and contracts, reform groups believed that cleaning the election process was one way to help undercut the political machines (and take back political power). Nast's cartoon illustrates voting fraud while exposing the larger corruption of the Tweed Ring. This 1871 cartoon is captioned with a quotation from Charles Dickens' novel Oliver Twist: "They no sooner heard the cry, than, guessing how the matter stood, they issued forth with great promptitude; and, shouting 'Stop Thief!' too, and joined in the pursuit like Good Citizens."

Source(s): Same as above

Lincoln Steffens in The Shame of he Cities articles thinks that America should look in the mirror, What do you think of what he says? - and is it as relevant in Theodore Roosevelt's day as it is now?

In reading about Theodore Roosevelt in this book - what do you think about what he said about TR for example?

Also was Theodore Roosevelt right when he told Steffens that he was getting into dangerous territory? Why or why not?

Lincoln Steffens, The Shame of the Cities

Annotation

In the 1890s, changes in printing technology made possible inexpensive magazines that could appeal to a broader and increasingly more literate middle-class audience. Given the reform impulses popular in the early 20th century, many of these magazines featured reform-oriented investigative reporting that became known as "muckraking" (so named by President Theodore Roosevelt after the muckrake in Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress who could "look no way but downward, with a muckrake in his hands").

In October 1902 McClure's Magazine published what many consider the first muckraking article, Lincoln Steffens' "Tweed Days in St. Louis." The "muckrakers" wrote on many subjects, such as child labor, prisons, religion, corporations, and insurance companies. But urban political corruption remained a particularly popular target, and in 1904 Steffens collected and published his writings on St. Louis, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York as The Shame of the Cities. The Introduction, below, suggested his overall conclusions about political corruption.

Lincoln Steffens wrote: "Because politics is business. That's what's the matter with it. That's what's the matter with everything—art, literature, religion, journalism, law, medicine—they're all business, and all—as you see them.

Make politics a sport, as they do in England, or a profession, as they do in Germany, and we'll have—well, something else than we have now, if we want it, which is another question. But don't try to reform politics with the banker, the lawyer, and the dry-goods merchant, for these are business men and there are two great hindrances to their achievement of reform: one is that they are different from, but no better than, the politicians; the other is that politics is not "their line." There are exceptions both ways. Many politicians have gone out into business and done well (Tammany ex-mayors, and nearly all the old bosses of Philadelphia are prominent financiers in their cities), and business men have gone into politics and done well (Mark Hanna, for example). They haven't reformed their adopted trades, however, though they have sometimes sharpened them most pointedly. The politician is a business man with a specialty. When a business man of some other line learns the business of politics, he is a politician, and there is not much reform left in him. Consider the United States Senate, and believe me.

The commercial spirit is the spirit of profit, not patriotism; of credit, not honor; of individual gain, not national prosperity; of trade and dickering, not principle. "My business is sacred," says the business man in his heart. "Whatever prospers my business, is good; it must be. Whatever hinders it, is wrong; it must be. A bribe is bad, that is, it is a bad thing to take; but it is not so bad to give one, not if it is necessary to my business." "Business is business" is not a political sentiment, but our politician has caught it. He takes essentially the same view of the bribe, only he saves his self-respect by piling all his contempt upon the bribe-giver, and he has the great advantage of candor. "It is wrong, maybe," he says, "but if a rich merchant can afford to do business with me for the sake of a convenience or to increase his already great wealth, I can afford, for the sake of a living, to meet him half way. I make no pretensions to virtue, not even on Sunday." And as for giving bad government or good, how about the merchant who gives bad goods or good goods, according to the demand?

But there is hope, not alone despair, in the commercialism of our politics. If our political leaders are to be always a lot of political merchants, they will supply any demand we may create. All we have to do is to establish a steady demand for good government. The bosses have us split up into parties. To him parties are nothing but means to his corrupt ends. He "bolts" his party, but we must not; the bribe-giver changes his party, from one election to another, from one county to another, from one city to another, but the honest voter must not. Why? Because if the honest voter cared no more for his party than the politician and the grafter, then the honest vote would govern, and that would be bad—for graft. It is idiotic, this devotion to a machine that is used to take our sovereignty from us. If we would leave parties to the politicians, and would vote not for the party, not even for men, but for the city, and the State, and the nation, we should rule parties, and cities, and States, and nation. If we would vote in mass on the more promising ticket, or, if the two are equally bad, would throw out the party that is in, and wait till the next election and then throw out the other party that is in— I say, the commercial politician would feel a demand for good government and he would supply it. That process would take a generation or more to complete, for the politicians now really do not know what good government is. But it has taken as long to develop bad government, and the politicians know what that is. If it would not "go," they would offer something else, and, if the demand were steady, they, being so commercial, would "deliver the goods."

But do the people want good government? Tammany says they don't. Are the people honest? Are the people better than Tammany? Are they better than the merchant and the politician? Isn't our corrupt government, after all, representative?

President Roosevelt has been sneered at for going about the country preaching, as a cure for our American evils, good conduct in the individual, simple honesty, courage, and efficiency. "Platitudes" the sophisticated say. Platitudes? If my observations have been true, the literal adoption of Mr. Roosevelt's reform scheme would result in a revolution, more radical and terrible to existing institutions, from the Congress to the Church, from the bank to the ward organization, than socialism or even than anarchy. Why, that would change all of us—not alone our neighbors, not alone the grafters, but you and me.

No, the contemned methods of our despised politics are the master methods of our braggart business, and the corruption that shocks us in public affairs we practice ourselves in our private concerns. There is no essential difference between the pull that gets your wife into society or for your book a favorable review, and that which gets a heeler into office, a thief out of jail, and a rich man's son on the board of directors of a corporation; none between the corruption of a labor union, a bank, and a political machine; none between a dummy director of a trust and the caucus-bound member of a legislature; none between a labor boss like Sam Parks, a boss of banks like John D. Rockefeller, a boss of railroads like J. P. Morgan, and a political boss like Matthew S. Quay. The boss is not a political, he is an American institution, the product of a freed people that have not the spirit to be free.

And it's all a moral weakness; a weakness right where we think we are strongest. Oh, we are good—on Sunday, and we are "fearfully patriotic" on the Fourth of July. But the bribe we pay to the janitor to prefer our interests to the landlord's, is the little brother of the bribe passed to the alderman to sell a city street, and the father of the air-brake stock assigned to the president of a railroad to have this life-saving invention adopted on his road. And as for graft, railroad passes, saloon and bawdy-house blackmail, and watered stock, all these belong to the same family. We are pathetically proud of our democratic institutions and our republican form of government, of our grand Constitution and our just laws. We are a free and sovereign people, we govern ourselves and the government is ours. But that is the point. We are responsible, not our leaders, since we follow them. We let them divert our loyalty from the United States to some "party"; we let them boss the party and turn our municipal democracies into autocracies and our republican nation into a plutocracy. We cheat our government and we let our leaders loot it, and we let them wheedle and bribe our sovereignty from us. True, they pass for us strict laws, but we are content to let them pass also bad laws, giving away public property in exchange; and our good, and often impossible, laws we allow to be used for oppression and blackmail. And what can we say? We break our own laws and rob our own government, the lady at the customhouse, the lyncher with his rope, and the captain of industry with his bribe and his rebate.

The spirit of graft and of lawlessness is the American spirit.

Source: Curators of the National Museum of American History

More: What George Washington Plunkitt had to say about the Shame of the Cities articles:

http://objectofhistory.org/objects/br...

Source: Thomas Nast, "Stop Thief!" Harper's Weekly, 1871

Detail on the above:

Thomas Nast's renowned illustrations in Harper's Weekly worked to expose the political corruption of the infamous machine run beginning in the 1860s by William "Boss" Tweed in New York City's Tammany Hall. Known for their corrupt dealings, the Democratic political machine used bribes, kickbacks, patronage, and sometimes engaged in voting fraud. At the same time, they often won immigrant support because they provided badly needed services to poor communities. Because Tammany Hall controlled voting, taxes, and contracts, reform groups believed that cleaning the election process was one way to help undercut the political machines (and take back political power). Nast's cartoon illustrates voting fraud while exposing the larger corruption of the Tweed Ring. This 1871 cartoon is captioned with a quotation from Charles Dickens' novel Oliver Twist: "They no sooner heard the cry, than, guessing how the matter stood, they issued forth with great promptitude; and, shouting 'Stop Thief!' too, and joined in the pursuit like Good Citizens."

Source(s): Same as above

message 58:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 10:40AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Robin wrote: "I support the plug for 'The Bully Pulpit'!"

If you want to talk about another book and not the one being discussed - you have to cite it (smile) - and we welcome all recommendations.

by

by

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Doris Kearns Goodwin

And that is only fine if it is not self promotion - which we know it is not in this case. So just add the proper citation and all is well.

If you want to talk about another book and not the one being discussed - you have to cite it (smile) - and we welcome all recommendations.

by

by

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Doris Kearns GoodwinAnd that is only fine if it is not self promotion - which we know it is not in this case. So just add the proper citation and all is well.

message 59:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 10:54AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Robin wrote: "I agree, Bentley, that Taft used TR to get what he wanted, and I agree with your parallel to Wilson's wife.

Taft was never as forthcoming about his platform as TR was. Like many politicians, he te..."

What is that saying - Every man needs a woman when his life is a mess because just like the game of chess, the Queen protects the King.

Taft had Nellie, FDR had Eleanor, Clinton had Hillary, Madison had Dolly, Wilson had Edith, John Adams had Abigail, Obama has Michelle - all of the Presidents that I can remember had very strong women for the most part as their wives. Not many were shrinking violets.

Taft was never as forthcoming about his platform as TR was. Like many politicians, he te..."

What is that saying - Every man needs a woman when his life is a mess because just like the game of chess, the Queen protects the King.

Taft had Nellie, FDR had Eleanor, Clinton had Hillary, Madison had Dolly, Wilson had Edith, John Adams had Abigail, Obama has Michelle - all of the Presidents that I can remember had very strong women for the most part as their wives. Not many were shrinking violets.

In connection with women having more rights in the West, I think that may have something to do with the western lifestyle. You would be more likely to see western women out working on the ranch, etc. - maybe their labor was more visible than that of other women? Pioneer women had proved that they were tough so they were rewarded with voting rights, maybe?

In connection with women having more rights in the West, I think that may have something to do with the western lifestyle. You would be more likely to see western women out working on the ranch, etc. - maybe their labor was more visible than that of other women? Pioneer women had proved that they were tough so they were rewarded with voting rights, maybe?

message 61:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 12:01PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

That is interesting - maybe the fact that folks were brave enough to pitch in and even go west developed a certain spirit and esprit de corps and men viewed their women differently and vice versa.

message 62:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 03:21PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

What did you think about the Democratic convention and the parties leaders ignoring suffragists' demands and refusing to even consider a resolution on race equality?

However even worse they did agree to a resolution to bar Asiatic immigrants who can not be amalgamated with our population from entering the United States!!!!

Then they were either delusional or brazen enough to say that "The Democratic party is the champion of equal rights and opportunities to all". Of course they were only talking about white men.

Topics for Discussion

1. Did the attitudes against minorities shock you (remember these were the times and the attitudes in 1908!)?

2. Who had determined that the Asiatic immigrants could not be amalgamated?

What do you think of the write-up from Harvard University on Asians and Asian Exclusion?

Asians and Asian Exclusion

http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/...

The Chinese and Japanese immigration of the second half of the nineteenth century began a new chapter in America’s religious history. The broad Confucian respect for family, popular temple Taoism with its deities of protection, and Buddhism in its many forms—all found their way to American shores. With the Indian immigration that began in the early twentieth century, Sikhs from the fertile farmlands of the Punjab added their traditions to this new burst of religious diversity.

This new encounter would have even more far-reaching theological challenges for the majority Christian population. Some Asian immigrants brought with them previous experience of Christianity, both negative and positive, through Christian mission efforts in Asia. Americans for their part had some knowledge of Asia, again through missions and through the literature of the Transcendentalists. On the whole, however, there was little but stereotypical knowledge to guide this encounter. Significantly, the first chapter in the Asian-American experience was set in the context of economic expansion and competition in the American West, where difference of any kind often became the excuse for antagonism.

Invectives against “Chinamen,” “Japs,” and “Ragheads” marred the first decades of America’s homegrown encounter with Asia. From the 1850s to the 1920s, anti-Asian agitation from the local to the national level was fueled by fear, stereotype, and racism. The agitation that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 grew to include other Asian immigrants. The Japanese and Korean exclusion movement dilated into the Asiatic Exclusion League, formed in 1908 to work for the exclusion of all Asian immigrants whom the League declared to be “utterly unfit and incapable of discharging the duties of American citizenship.”

For the Chinese who began to come to America in the 1850s, California was known as Gam Saan, Gold Mountain. The gold rush was in full steam. For those who were not lucky with gold, there were jobs on the railroads or in factories. Some Californians praised the arrival of the Chinese, whom they called “the Celestials” as part of the diverse, burgeoning growth of America in the Industrial Age. In 1852, the Daily Alta California newspaper expressed confidence that the Chinese would soon “vote at the same polls, study at the same schools and bow at the same altar as our own countrymen.” This confidence was not borne out. The new state of California proposed Chinese exclusion legislation, in support of which the governor scoffed at the very idea that the Chinese could ever vote intelligently. When Chinese and Japanese students were permitted to attend schools, the schools were separate by legislative order. And, of course, the Chinese worshipped at their own altars. The first Buddhist and Taoist temples opened in San Francisco in the 1850s and, eventually, there were hundreds of small temples on the West Coast and in the frontier territories of the Rocky Mountains.

Protestant familiarity with Chinese religion was sketchy at best. The Chinese were routinely caricatured as “pagans” and “heathens,” labels that emphasized both racial differences and non-Christian allegiances. One missionary to China had claimed that “the four marks of Paganism were Tauism, Boodhism, ancestor worship and opium addiction.” Bret Harte’s poem “The Heathen Chinee,” depicting a cheating Chinese gambler, was published in 1870 and reprinted in newspapers across the country. Family-minded Christian citizens condemned the “bachelor societies” of which Chinatowns, large and small, were composed. Such groups of men living together were said to be breeding grounds for drugs and prostitution. At the same time, the state moved to prohibit the wives or families of Chinese from coming to the U.S., thus contributing to the very social problems they were so quick to condemn.

The Japanese came in the 1860s. Determined to avoid the negative stereotypes of Chinese immigrants in the U.S., the government of Japan set a strict “standard” for people allowed to emigrate. Many were literate and skilled workers, and twenty to thirty percent were women. Nonetheless, some Americans used anti-Chinese sentiment to fan the flames of anti-Japanese feeling as well. An 1891 San Francisco newspaper carried a headline that summed up the fears of many Americans: “Undesirables: Another phase in the immigration from Asia; Japanese taking the place of Chinese; Importation of Contract Laborers and Women.” Despite their best efforts, the Japanese were lumped together with the Chinese.

For the Japanese, the 1909 “Gentleman’s Agreement” permitted the immigration of the family members of laborers already in America, but prohibited any further laborers from coming. Because marriage in Japan could legally take place by proxy and then be formalized in America, “picture brides,” known to the husband only by a photograph sent from Japan, flocked to California shores. For the Japanese in America, the encouragement of family life helped balance the ratio of men to women and allowed for a second generation to develop, often easing the way for the older immigrants in the community.

For most Euro-Americans of this period, judgments about the “otherness” of the Japanese focused on their dress, the picture bride system, and Buddhism. Christian missionaries saw the opportunity for evangelism right here at home. As a group of Japanese Buddhists put it to their headquarters in Japan, “Towns bristle with Christian churches and sermons, the prayers of the missionaries shake through the cities with church bells. To strong Buddhists like ourselves, these pressures mean nothing. However, we sometimes get reports of frivolous Japanese who surrender themselves to accept the heresy—as a hungry man does not have much choice but to eat what is offered him.”

Such calls for spiritual leadership from the burgeoning Buddhist community were heard by a young Jodo Shinshu priest, Soryu Kagahi, who arrived in Hawaii from Japan in March of 1889 to engage in a mission of his own. He established the first Japanese Buddhist temple in Hawaii, while also providing much needed guidance to the physically and spiritually taxed workers on Hawaiian plantations. Yet Christians unsure about a religious tradition they had never encountered, took note of Kagahi’s efforts with concern. The Hawaiian Evangelical Association, for instance, warned its members against “a Buddhist organization among us, which encourages drinking,” a rumor which clearly indicates how much such groups still needed to learn about the new religious traditions being transplanted in their soil.

The lotus flower of Buddhism began to bloom in Hawaii, and a decade later on the American mainland. But Japanese Buddhists themselves were at first uneasy about how “Buddhist” they should be. Kagahi, for instance, attempting to reach out to the Christian culture he encountered, suggested that Buddhist missionaries should use language that placed the Eternal Buddha and the Christian God under the same umbrella of the “Absolute Reality.” Such “blending” of theological terms would become more common in the future, as Japanese Buddhists sought to make their religious tradition “relevant” to both the Christian and “scientific” worlds of twentieth century America. But in the late nineteenth century Japanese Buddhists were still on the defensive.

As the century turned, Japanese immigrants struggled between seeking the guidance of their faith to help them in their new lives and leaving that faith behind in the quest for “accommodation.” Such a struggle divided the Japanese community into Buddhist practitioners who were eyed with suspicion by the dominant culture and Christian converts who were ambivalently welcomed. This division created tensions within the immigrant population that reproduced themselves in families and in the hearts and minds of individuals who strove to be culturally “Western,” but religiously Buddhist.

Sikhs from India also brought a new religious tradition to America. They were referred to generically as “Hindus,” meaning virtually anyone from India. There were, however, only a few Hindus and Muslims among the Punjabi workers who came from 1900-1910 to British Columbia and then worked their way south to Washington, Oregon, and California. On the whole, they were Sikhs. They wore turbans wrapped around their uncut hair in faithfulness to one of the five observances of every devout Sikh—to let the hair grow, as God and nature intended. Again, it was one distinctive characteristic that was singled out for caricature, earning them the name “ragheads.”

Like the Chinese, the Sikhs came as single men, some intending eventually to return to the Punjab, others hoping to make a new life in America. Most of them eventually settled into the agricultural work they knew well from the fields of home. They organized a gurdwara in Stockton, California in 1912 which became the primary social, cultural, and religious center for the Sikhs of the Central Valley for more than fifty years. Due to the laws prohibiting the immigration of wives and family members from the Punjab, those who wanted a settled, married life often married Mexican women with strong Catholic extended families. Thus, the first major “interreligious” encounter was often in the context of marriage. It created a subculture of Mexican-Sikhs who, with names like Jesús Singh, observed Sikh festivals with the community in Stockton and were, at the same time, baptized Catholics.

Much of America’s anti-Asian agitation and sentiment from the 1850s to the 1920s was rooted in economic and not religious terms. Chinese workers were hired to replace striking workers at the North Adams shoe factory in Massachusetts. Sikh mill workers were perceived to be a threat to those seeking employment in the lumber industry in Bellingham, Washington. Explicitly anti-Chinese agitation culminated in the 1882 Federal Chinese Exclusion Act, which was renewed and broadened in 1892 and in 1902. The Congressional debate over exclusion often turned from economics to the question of cultural and religious compatibility.

The federal Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924 established a quota system for immigration which also excluded those ineligible for naturalization as citizens. The Federal Naturalization Law of 1790 had limited the naturalization of foreign-born persons to “white” persons only. As Asian immigrants came to America, this law became the basis of excluding Asians from citizenship. In 1922, Tad Ozawa, a Japanese man who had lived most of his life in America, graduated from Berkeley High School and the University of California, was ruled to be ineligible for citizenship. In 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi-born Sikh who had served in the U.S. Army in World War I was also ruled ineligible for citizenship. By 1924 the immigration door from Asia to America was effectively shut.

Source: The Pluralism Project - Harvard University

However even worse they did agree to a resolution to bar Asiatic immigrants who can not be amalgamated with our population from entering the United States!!!!

Then they were either delusional or brazen enough to say that "The Democratic party is the champion of equal rights and opportunities to all". Of course they were only talking about white men.

Topics for Discussion

1. Did the attitudes against minorities shock you (remember these were the times and the attitudes in 1908!)?

2. Who had determined that the Asiatic immigrants could not be amalgamated?

What do you think of the write-up from Harvard University on Asians and Asian Exclusion?

Asians and Asian Exclusion

http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/...

The Chinese and Japanese immigration of the second half of the nineteenth century began a new chapter in America’s religious history. The broad Confucian respect for family, popular temple Taoism with its deities of protection, and Buddhism in its many forms—all found their way to American shores. With the Indian immigration that began in the early twentieth century, Sikhs from the fertile farmlands of the Punjab added their traditions to this new burst of religious diversity.

This new encounter would have even more far-reaching theological challenges for the majority Christian population. Some Asian immigrants brought with them previous experience of Christianity, both negative and positive, through Christian mission efforts in Asia. Americans for their part had some knowledge of Asia, again through missions and through the literature of the Transcendentalists. On the whole, however, there was little but stereotypical knowledge to guide this encounter. Significantly, the first chapter in the Asian-American experience was set in the context of economic expansion and competition in the American West, where difference of any kind often became the excuse for antagonism.

Invectives against “Chinamen,” “Japs,” and “Ragheads” marred the first decades of America’s homegrown encounter with Asia. From the 1850s to the 1920s, anti-Asian agitation from the local to the national level was fueled by fear, stereotype, and racism. The agitation that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 grew to include other Asian immigrants. The Japanese and Korean exclusion movement dilated into the Asiatic Exclusion League, formed in 1908 to work for the exclusion of all Asian immigrants whom the League declared to be “utterly unfit and incapable of discharging the duties of American citizenship.”

For the Chinese who began to come to America in the 1850s, California was known as Gam Saan, Gold Mountain. The gold rush was in full steam. For those who were not lucky with gold, there were jobs on the railroads or in factories. Some Californians praised the arrival of the Chinese, whom they called “the Celestials” as part of the diverse, burgeoning growth of America in the Industrial Age. In 1852, the Daily Alta California newspaper expressed confidence that the Chinese would soon “vote at the same polls, study at the same schools and bow at the same altar as our own countrymen.” This confidence was not borne out. The new state of California proposed Chinese exclusion legislation, in support of which the governor scoffed at the very idea that the Chinese could ever vote intelligently. When Chinese and Japanese students were permitted to attend schools, the schools were separate by legislative order. And, of course, the Chinese worshipped at their own altars. The first Buddhist and Taoist temples opened in San Francisco in the 1850s and, eventually, there were hundreds of small temples on the West Coast and in the frontier territories of the Rocky Mountains.

Protestant familiarity with Chinese religion was sketchy at best. The Chinese were routinely caricatured as “pagans” and “heathens,” labels that emphasized both racial differences and non-Christian allegiances. One missionary to China had claimed that “the four marks of Paganism were Tauism, Boodhism, ancestor worship and opium addiction.” Bret Harte’s poem “The Heathen Chinee,” depicting a cheating Chinese gambler, was published in 1870 and reprinted in newspapers across the country. Family-minded Christian citizens condemned the “bachelor societies” of which Chinatowns, large and small, were composed. Such groups of men living together were said to be breeding grounds for drugs and prostitution. At the same time, the state moved to prohibit the wives or families of Chinese from coming to the U.S., thus contributing to the very social problems they were so quick to condemn.

The Japanese came in the 1860s. Determined to avoid the negative stereotypes of Chinese immigrants in the U.S., the government of Japan set a strict “standard” for people allowed to emigrate. Many were literate and skilled workers, and twenty to thirty percent were women. Nonetheless, some Americans used anti-Chinese sentiment to fan the flames of anti-Japanese feeling as well. An 1891 San Francisco newspaper carried a headline that summed up the fears of many Americans: “Undesirables: Another phase in the immigration from Asia; Japanese taking the place of Chinese; Importation of Contract Laborers and Women.” Despite their best efforts, the Japanese were lumped together with the Chinese.

For the Japanese, the 1909 “Gentleman’s Agreement” permitted the immigration of the family members of laborers already in America, but prohibited any further laborers from coming. Because marriage in Japan could legally take place by proxy and then be formalized in America, “picture brides,” known to the husband only by a photograph sent from Japan, flocked to California shores. For the Japanese in America, the encouragement of family life helped balance the ratio of men to women and allowed for a second generation to develop, often easing the way for the older immigrants in the community.

For most Euro-Americans of this period, judgments about the “otherness” of the Japanese focused on their dress, the picture bride system, and Buddhism. Christian missionaries saw the opportunity for evangelism right here at home. As a group of Japanese Buddhists put it to their headquarters in Japan, “Towns bristle with Christian churches and sermons, the prayers of the missionaries shake through the cities with church bells. To strong Buddhists like ourselves, these pressures mean nothing. However, we sometimes get reports of frivolous Japanese who surrender themselves to accept the heresy—as a hungry man does not have much choice but to eat what is offered him.”

Such calls for spiritual leadership from the burgeoning Buddhist community were heard by a young Jodo Shinshu priest, Soryu Kagahi, who arrived in Hawaii from Japan in March of 1889 to engage in a mission of his own. He established the first Japanese Buddhist temple in Hawaii, while also providing much needed guidance to the physically and spiritually taxed workers on Hawaiian plantations. Yet Christians unsure about a religious tradition they had never encountered, took note of Kagahi’s efforts with concern. The Hawaiian Evangelical Association, for instance, warned its members against “a Buddhist organization among us, which encourages drinking,” a rumor which clearly indicates how much such groups still needed to learn about the new religious traditions being transplanted in their soil.

The lotus flower of Buddhism began to bloom in Hawaii, and a decade later on the American mainland. But Japanese Buddhists themselves were at first uneasy about how “Buddhist” they should be. Kagahi, for instance, attempting to reach out to the Christian culture he encountered, suggested that Buddhist missionaries should use language that placed the Eternal Buddha and the Christian God under the same umbrella of the “Absolute Reality.” Such “blending” of theological terms would become more common in the future, as Japanese Buddhists sought to make their religious tradition “relevant” to both the Christian and “scientific” worlds of twentieth century America. But in the late nineteenth century Japanese Buddhists were still on the defensive.

As the century turned, Japanese immigrants struggled between seeking the guidance of their faith to help them in their new lives and leaving that faith behind in the quest for “accommodation.” Such a struggle divided the Japanese community into Buddhist practitioners who were eyed with suspicion by the dominant culture and Christian converts who were ambivalently welcomed. This division created tensions within the immigrant population that reproduced themselves in families and in the hearts and minds of individuals who strove to be culturally “Western,” but religiously Buddhist.

Sikhs from India also brought a new religious tradition to America. They were referred to generically as “Hindus,” meaning virtually anyone from India. There were, however, only a few Hindus and Muslims among the Punjabi workers who came from 1900-1910 to British Columbia and then worked their way south to Washington, Oregon, and California. On the whole, they were Sikhs. They wore turbans wrapped around their uncut hair in faithfulness to one of the five observances of every devout Sikh—to let the hair grow, as God and nature intended. Again, it was one distinctive characteristic that was singled out for caricature, earning them the name “ragheads.”

Like the Chinese, the Sikhs came as single men, some intending eventually to return to the Punjab, others hoping to make a new life in America. Most of them eventually settled into the agricultural work they knew well from the fields of home. They organized a gurdwara in Stockton, California in 1912 which became the primary social, cultural, and religious center for the Sikhs of the Central Valley for more than fifty years. Due to the laws prohibiting the immigration of wives and family members from the Punjab, those who wanted a settled, married life often married Mexican women with strong Catholic extended families. Thus, the first major “interreligious” encounter was often in the context of marriage. It created a subculture of Mexican-Sikhs who, with names like Jesús Singh, observed Sikh festivals with the community in Stockton and were, at the same time, baptized Catholics.

Much of America’s anti-Asian agitation and sentiment from the 1850s to the 1920s was rooted in economic and not religious terms. Chinese workers were hired to replace striking workers at the North Adams shoe factory in Massachusetts. Sikh mill workers were perceived to be a threat to those seeking employment in the lumber industry in Bellingham, Washington. Explicitly anti-Chinese agitation culminated in the 1882 Federal Chinese Exclusion Act, which was renewed and broadened in 1892 and in 1902. The Congressional debate over exclusion often turned from economics to the question of cultural and religious compatibility.

The federal Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924 established a quota system for immigration which also excluded those ineligible for naturalization as citizens. The Federal Naturalization Law of 1790 had limited the naturalization of foreign-born persons to “white” persons only. As Asian immigrants came to America, this law became the basis of excluding Asians from citizenship. In 1922, Tad Ozawa, a Japanese man who had lived most of his life in America, graduated from Berkeley High School and the University of California, was ruled to be ineligible for citizenship. In 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi-born Sikh who had served in the U.S. Army in World War I was also ruled ineligible for citizenship. By 1924 the immigration door from Asia to America was effectively shut.

Source: The Pluralism Project - Harvard University

message 63:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 12:46PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

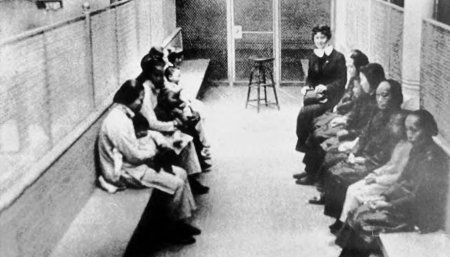

Chinese and Japanese women waiting within an enclosure to be processed at the Angel Island Reception Center during the 1920’s, a period during which very few Asian immigrants were admitted to the United States. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Japanese immigrants at work in a laundry (around 1900) - Oakland Library

See the Gentlemen's Agreement:

http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gentle...

Picture Brides:

http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Pictur...

Picture brides arriving at Angel Island, California, c. 1910.

Courtesy of California State Parks, Number 090-706

Michael wrote: "Vincent wrote: "I am wondering about the choice of title "Unreasonable Men" - are they just men with different reasons and different goals and who seem to be unreasonable to the Aldrichs and other ..."

Michael wrote: "Vincent wrote: "I am wondering about the choice of title "Unreasonable Men" - are they just men with different reasons and different goals and who seem to be unreasonable to the Aldrichs and other ..."Thanks - yes - I remember now but this question just popped into my head reading the title of the book as it lay on the table.

I had forgotten

Sorry

Like everyone else I was intrigued by the fact of Taft's winning smile, his love of golf and fishing, and his not really wanting to be president.

Like everyone else I was intrigued by the fact of Taft's winning smile, his love of golf and fishing, and his not really wanting to be president. The thing that struck me most in this chapter was the Democrats idea that equal opportunity for all meant all white men.

message 67:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 22, 2016 03:24PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

I know - wasn't that the killer. I think Nellie wanted to be President (smile). And her second choice was having her husband be President - he was quite reluctant. It strikes me so odd that a country founded on religious values by folks seeking freedom that even by 1908 - 1910 things were still the way they were - not just African Americans, but Women and other Minorities like the Asians were not very well treated and obviously other immigrants too. And that it was the Democrats' idea does seem worse doesn't it (lol)? Thankfully at least by the time of Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King and many many others including some not so peaceful like Malcolm X - things improved a lot but certainly we still have underlying issues even today. Women can vote now but they certainly are still fighting an uphill battle for even equal pay.

Yes, women are still fighting that uphill battle for equal pay.

Yes, women are still fighting that uphill battle for equal pay. I was surprised that in 1908 they had a woman delegate. I did not expect that women had gotten that involved in politics since they did not yet have the right to vote.

Like others, I was very interested in Nellie Taft. Thanks for posting the recommendation on the book about her, Bentley! I love the line on page 142 where Taft says "However, as my wife is the politician and she will be able to meet all these issues, perhaps we can keep a stiff upper lip and overcome the obstacles that just at present seem formidable." I think that some first wives don't get near enough credit.

I know next to nothing about Taft and found him to be quite a character that seemed to have little concern about the election. It seemed more like Roosevelt was the one running for him while he took it easy on the links.

It was a Dee-lightful chapter.

Teri - you are right - I got quite a chuckle at that quote.

I agree - especially if they have a Taft to contend with who is off golfing and fishing and not attending to business and you are the wife and you get called to a meeting by the president - basically wanting to ask - What is he doing????

I agree - especially if they have a Taft to contend with who is off golfing and fishing and not attending to business and you are the wife and you get called to a meeting by the president - basically wanting to ask - What is he doing????

Great chapter! Like many of you I had no idea about Taft's smile being a big deal Seems like that and TR's support did it for him. Strange that it took so little to win back then. Thank you for posting all the pictures I enjoyed them much. This is great reading, because it falls into the same timeline as Thunderstruck which I'm reading at the same time.

Great chapter! Like many of you I had no idea about Taft's smile being a big deal Seems like that and TR's support did it for him. Strange that it took so little to win back then. Thank you for posting all the pictures I enjoyed them much. This is great reading, because it falls into the same timeline as Thunderstruck which I'm reading at the same time. by

by

Bentley wrote: "Transformations:

Bentley wrote: "Transformations:In this chapter I was struck by the number of men who were being transformed from one set of personality traits or beliefs to another.

Let us begin at the beginning of the chapt..."

I was surprised by Lincoln Steffens' change of mind about his career as a muckraker. I'm so used to thinking of him in that role that I guess it never occurred to me that he might get disillusioned.

William Jennings Bryan was another surprise. What I knew about him was his role as the prosecutor in the Scopes' trial, that he ran unsuccessfully for President three times and was obsessed about changing the gold standard. So it was interesting to read about how he actually changed to try and win the election. He really seemed to react like a politician rather than simply an orator or biblical defender.

On a personal note, I wish Mrs. Taft had written a book on how you get husbands to do what you want them to. She certainly seems to have been good at it.

I have read the chapter a couple of times at least - maybe more when you are moderating - and the last time - all of a sudden - I realized that the major players were all going through transitions or transformations. They all were not acting like themselves. And in each and every case - you had to ask yourself why.

In some respects TR was right about the muckraker and "light".

Bryan seemed to be the most like the politicians that are running this year - trying to adopt a new skin to seem more palatable. Taft really could not pull it off - he was just being Taft and luckily they liked his smile and figured he would be OK since TR liked him so much.

And of course there was the Nellie factor. I think Taft actually did what he wanted to do and Nellie just cleaned up after him. I do not remember reading that she was out golfing or fishing.

In some respects TR was right about the muckraker and "light".

Bryan seemed to be the most like the politicians that are running this year - trying to adopt a new skin to seem more palatable. Taft really could not pull it off - he was just being Taft and luckily they liked his smile and figured he would be OK since TR liked him so much.

And of course there was the Nellie factor. I think Taft actually did what he wanted to do and Nellie just cleaned up after him. I do not remember reading that she was out golfing or fishing.

I never thought about Bryan being like today's bunch but I think you're right. They all are changing or "transitioning" in some way although Trump may be just rolling with the punches rather than truly trying to change.

I never thought about Bryan being like today's bunch but I think you're right. They all are changing or "transitioning" in some way although Trump may be just rolling with the punches rather than truly trying to change.I don't know about Nellie. She seems pretty formidable but I think Taft may have humoured her a little as he seems to have gotten to do pretty much what he wanted. Eventually, he even got that seat on the Court.

Yes and he wanted that.

Bernie from socialist to progressive

Hillary from moderate to more towards the left

Cruz from far right - trying to appear to be progressive

Bush - moderate trying to appease the far right

Carson - far right - trying to appear more moderate

Trump - was a Democrat - now a Republican - was moderate and in some instances more to the left of center and now is trying to pitch to the conservatives and far right

Bernie from socialist to progressive

Hillary from moderate to more towards the left

Cruz from far right - trying to appear to be progressive

Bush - moderate trying to appease the far right

Carson - far right - trying to appear more moderate

Trump - was a Democrat - now a Republican - was moderate and in some instances more to the left of center and now is trying to pitch to the conservatives and far right

These are the things that stood out for me from chapter 6.

These are the things that stood out for me from chapter 6.La Follette states how there is misrepresentation of the government shown to “special privileges” and he put the senators on record in trying to achieve the desired bill. This is a main theme for LF. I was surprised he sort of endorsed Taft as a "progressive in principle".

We are introduced to William Taft and how the people love his smile. I never knew this about him but also do not know much about Taft. I found his wife Nellie intriquing and want to read more about her.

On page 129, the DNC convention is in Denver, the women rode astride horses and had full voting rights. Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming had full voting rights for women. TR was less supportive of women voting and stated it was not important at this time. Taft said it would come, but it was not the time. In the DNC, William Jennings Bryan endorsed equality and embraced progressive policies but the south opposed them. The women in the midwest had much more freedom and rights then in the east. TR and Taft were not very progressive for the equality of women.

I have to credit Taft for the announcement he made which I thought was more progressive and independent when he stated that he was going to have an honest revision of the tariff. This was a topic that TR avoided for 7 years because he felt it would shatter the party. I am anxious to see what happens with this.

The other noticeable actions in this chapter was with Aldrich after his trip to Europe when he noticed that the US has had no moentary system. He wanted his legacy to be built on the American monetary sytem. He is pondering on how to establish a Central Bank which would be a radical change. It will be intersting to see how he pursues it.

Bentley wrote: "Just a suggestion to folks who want to get some books and money is an object. They do now - I think it has a been a few years since it was purchased but goodreads has been able to maintain their ow..."

Bentley wrote: "Just a suggestion to folks who want to get some books and money is an object. They do now - I think it has a been a few years since it was purchased but goodreads has been able to maintain their ow..."I want to thank all of the moderators and you for your hard work and for volunteering so much time to HBC, my favorite book club. And like you Bentley, books are among my favorite things after my dog and family. I have so many of them and could not live with out them.

I was glad to know that in his time, people liked Taft's smile. It seems to be a forgotten fact of history, but meanwhile, everyone knows about the embarrassing bathtub story. In discussing that story with a group (at the memory-enhancing trivia session at my mother's assisted living center), someone observed that if the bathtub story had happened today, someone would have leaked a picture to the Internet. And if it had happened to Trump, he'd probably leak the picture himself.

I was glad to know that in his time, people liked Taft's smile. It seems to be a forgotten fact of history, but meanwhile, everyone knows about the embarrassing bathtub story. In discussing that story with a group (at the memory-enhancing trivia session at my mother's assisted living center), someone observed that if the bathtub story had happened today, someone would have leaked a picture to the Internet. And if it had happened to Trump, he'd probably leak the picture himself. Interesting about Nellie Taft and the cherry blossoms. I LOVE those trees!

Helga wrote: "Bentley wrote: "Just a suggestion to folks who want to get some books and money is an object. They do now - I think it has a been a few years since it was purchased but goodreads has been able to m..."

Thank you Helga and I am glad that you enjoy it. It was interesting how the West was more enlightened about women's rights.

Thank you Helga and I am glad that you enjoy it. It was interesting how the West was more enlightened about women's rights.

Kressel wrote: "I was glad to know that in his time, people liked Taft's smile. It seems to be a forgotten fact of history, but meanwhile, everyone knows about the embarrassing bathtub story. In discussing that st..."

Very funny anecdote Kressel and so true

Very funny anecdote Kressel and so true

Also, I appreciate the vivid description of the reaction to "the Cross of Gold" speech. It's one of those things in history I know about, but not with any detail. Now I know a little more. One of these days I'm going to read Almost President: The Men Who Lost the Race but Changed the Nation. Bryan gets a chapter, as does Al Gore.

Also, I appreciate the vivid description of the reaction to "the Cross of Gold" speech. It's one of those things in history I know about, but not with any detail. Now I know a little more. One of these days I'm going to read Almost President: The Men Who Lost the Race but Changed the Nation. Bryan gets a chapter, as does Al Gore.Citation:

by Scott Farris (no photo)

by Scott Farris (no photo)

message 85:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 23, 2016 11:08AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Folks, Week Seven is now open and we move to that thread and its assignment:

The seventh week's reading assignment is:

Week Seven - May 23rd - May 29th

Chapter Seven - The Tariff - (pages 123 - 142)

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

For those of you who need to catch up check each of the previous six threads including this one and make sure that you have posted on that thread and it is noted. If in fact you have not posted, make sure you respond on that thread to the topics for discussion and the next time I do an update - I will note your new responses so that you can get caught up.

You can still post on all of the Weekly threads to get caught up or if you are starting out new and want to read the book by all means post any time.

Book Recipients however should get caught up as soon as you can and are able (we realize everybody reads at different speeds) - we have reached the mid point of the book discussion. There are ten chapters in the book and this is Week Seven.

So try to catch up on your posting and your reading.

Here are the links to the previous Weekly Chapters to check your progress:

Week Six - https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Week Five - https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Week Four

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Week Three

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Week Two

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Week One

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

And also part of the T's and C's is interacting with the author and asking a question or two - here is that link to the Q&A thread:

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Take advantage of the author being with us on this journey.

The seventh week's reading assignment is:

Week Seven - May 23rd - May 29th

Chapter Seven - The Tariff - (pages 123 - 142)

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

For those of you who need to catch up check each of the previous six threads including this one and make sure that you have posted on that thread and it is noted. If in fact you have not posted, make sure you respond on that thread to the topics for discussion and the next time I do an update - I will note your new responses so that you can get caught up.

You can still post on all of the Weekly threads to get caught up or if you are starting out new and want to read the book by all means post any time.

Book Recipients however should get caught up as soon as you can and are able (we realize everybody reads at different speeds) - we have reached the mid point of the book discussion. There are ten chapters in the book and this is Week Seven.

So try to catch up on your posting and your reading.

Here are the links to the previous Weekly Chapters to check your progress:

Week Six - https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...