The Pickwick Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Book I Chapters 05 - 08

Chapter 6 is titled "The Father of the Marshalsea", and we find that this Father is Little Dorrit's father. The chapter opens with this description of the Marshalsea:

Chapter 6 is titled "The Father of the Marshalsea", and we find that this Father is Little Dorrit's father. The chapter opens with this description of the Marshalsea:"Thirty years ago there stood, a few doors short of the church of Saint George, in the borough of Southwark, on the left-hand side of the way going southward, the Marshalsea Prison. It had stood there many years before, and it remained there some years afterwards; but it is gone now, and the world is none the worse without it.

It was an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back, so that there were no back rooms; environed by a narrow paved yard, hemmed in by high walls duly spiked at top. Itself a close and confined prison for debtors, it contained within it a much closer and more confined jail for smugglers. Offenders against the revenue laws, and defaulters to excise or customs who had incurred fines which they were unable to pay, were supposed to be incarcerated behind an iron-plated door closing up a second prison, consisting of a strong cell or two, and a blind alley some yard and a half wide, which formed the mysterious termination of the very limited skittle-ground in which the Marshalsea debtors bowled down their troubles."

Amy's father is described as a very amiable and very helpless middle-aged gentleman, who was going out again directly. We are told the Marshalsea never held a debtor who was not, or at least it never held a debtor who didn't think he was going out directly. This had me wondering, if people in debt were arrested and locked up until they paid what they owed, how were they supposed to earn the money since they were in prison? We're told Mr. Dorrit doesn't think he will bother to unpack his portmanteau because he won't be there long. We find during a conversation between Mr. Dorrit and the turnkey that Mrs. Dorrit and their two children will be arriving the next day:

'I fear—I hope it is not against the rules—that she will bring the children.'

'The children?' said the turnkey. 'And the rules? Why, lord set you up like a corner pin, we've a reg'lar playground o' children here. Children! Why we swarm with 'em. How many a you got?'

'Two,' said the debtor, lifting his irresolute hand to his lip again, and turning into the prison.

The turnkey followed him with his eyes. 'And you another,' he observed to himself, 'which makes three on you. And your wife another, I'll lay a crown. Which makes four on you. And another coming, I'll lay half-a-crown. Which'll make five on you. And I'll go another seven and sixpence to name which is the helplessest, the unborn baby or you!'

He was right in all his particulars. She came next day with a little boy of three years old, and a little girl of two, and he stood entirely corroborated.

'Got a room now; haven't you?' the turnkey asked the debtor after a week or two.

'Yes, I have got a very good room.'

'Any little sticks a coming to furnish it?' said the turnkey.

'I expect a few necessary articles of furniture to be delivered by the carrier, this afternoon.'

'Missis and little 'uns a coming to keep you company?' asked the turnkey.

'Why, yes, we think it better that we should not be scattered, even for a few weeks.'

'Even for a few weeks, of course,' replied the turnkey. And he followed him again with his eyes, and nodded his head seven times when he was gone."

I find it hard to imagine an entire family living in prison, but at that time they were allowed to accompany the prisoner and share the cell. When they move into the Marshalea the Dorrits have two children, Fanny and Edward, who everyone calls Tip. As for the reason Mr. Dorrit is in debt in the first place is described this way:

"The affairs of this debtor were perplexed by a partnership, of which he knew no more than that he had invested money in it; by legal matters of assignment and settlement, conveyance here and conveyance there, suspicion of unlawful preference of creditors in this direction, and of mysterious spiriting away of property in that; and as nobody on the face of the earth could be more incapable of explaining any single item in the heap of confusion than the debtor himself, nothing comprehensible could be made of his case. To question him in detail, and endeavour to reconcile his answers; to closet him with accountants and sharp practitioners, learned in the wiles of insolvency and bankruptcy; was only to put the case out at compound interest and incomprehensibility. The irresolute fingers fluttered more and more ineffectually about the trembling lip on every such occasion, and the sharpest practitioners gave him up as a hopeless job."

And so the family are now all settled in the prison and rather than being released in a few weeks, six months later Amy is born there in the Marshalea. When Mr. Dorrit makes the comment to the doctor - another locked up debtor - that he never thought his daughter would be born in a prison the doctor seems to think it is a fine place for just about anything.

"A little more elbow-room is all we want here. We are quiet here; we don't get badgered here; there's no knocker here, sir, to be hammered at by creditors and bring a man's heart into his mouth. Nobody comes here to ask if a man's at home, and to say he'll stand on the door mat till he is. Nobody writes threatening letters about money to this place. It's freedom, sir, it's freedom! I have had to-day's practice at home and abroad, on a march, and aboard ship, and I'll tell you this: I don't know that I have ever pursued it under such quiet circumstances as here this day. Elsewhere, people are restless, worried, hurried about, anxious respecting one thing, anxious respecting another. Nothing of the kind here, sir. We have done all that—we know the worst of it; we have got to the bottom, we can't fall, and what have we found? Peace. That's the word for it. Peace.' With this profession of faith, the doctor, who was an old jail-bird, and was more sodden than usual, and had the additional and unusual stimulus of money in his pocket, returned to his associate and chum in hoarseness, puffiness, red-facedness, all-fours, tobacco, dirt, and brandy."

Dickens tells us that Mr.Dorrit is beginning to feel the same way, he may be locked in, but the lock kept his troubles out. Here he was relieved from the perplexed affairs that nothing would make plain, his children were known here and played in the yard regularly. They are there for a few years when the turnkey tells him they are getting proud of him there and that he is the oldest inhabitant there. When they have been there eight years Mrs. Dorrit dies. She had been languishing away—of her own inherent weakness - whatever that means - and although Mr. Dorrit shuts himself up in his room for a fortnight after her death, he is over it in a month or two and the children are back to playing in the yard.

The turnkey is the only one who had been at the prison even longer than the Dorrit family, but now his health begins to fail. We're told:

"Time went on, and the turnkey began to fail. His chest swelled, and his legs got weak, and he was short of breath. The well-worn wooden stool was 'beyond him,' he complained. He sat in an arm-chair with a cushion, and sometimes wheezed so, for minutes together, that he couldn't turn the key. When he was overpowered by these fits, the debtor often turned it for him.

'You and me,' said the turnkey, one snowy winter's night when the lodge, with a bright fire in it, was pretty full of company, 'is the oldest inhabitants. I wasn't here myself above seven year before you. I shan't last long. When I'm off the lock for good and all, you'll be the Father of the Marshalsea.'

The turnkey went off the lock of this world next day. His words were remembered and repeated; and tradition afterwards handed down from generation to generation—a Marshalsea generation might be calculated as about three months—that the shabby old debtor with the soft manner and the white hair, was the Father of the Marshalsea."

So now Mr. Dorrit is the Father of the Marshalsea and very proud of it I think. All new-comers are now presented to him when they first arrive and he welcomes them to the prison. Letters are put under his door at night enclosing different sums of money, left for the Father of the Marshalsea 'With the compliments of a collegian taking leave.' Eventually he begins attending the debtors being released to the gate and taking leave of them there where they would usually leave him a "gift" of money as they left. This all seems very silly to me, on the part of Mr. Dorrit anyway. The chapter ends with this:

"One afternoon he had been doing the honours of the place to a rather large party of collegians, who happened to be going out, when, as he was coming back, he encountered one from the poor side who had been taken in execution for a small sum a week before, had 'settled' in the course of that afternoon, and was going out too. The man was a mere Plasterer in his working dress; had his wife with him, and a bundle; and was in high spirits.

'God bless you, sir,' he said in passing.

'And you,' benignantly returned the Father of the Marshalsea.

They were pretty far divided, going their several ways, when the Plasterer called out, 'I say!—sir!' and came back to him.

'It ain't much,' said the Plasterer, putting a little pile of halfpence in his hand, 'but it's well meant.'

The Father of the Marshalsea had never been offered tribute in copper yet. His children often had, and with his perfect acquiescence it had gone into the common purse to buy meat that he had eaten, and drink that he had drunk; but fustian splashed with white lime, bestowing halfpence on him, front to front, was new.

'How dare you!' he said to the man, and feebly burst into tears.

The Plasterer turned him towards the wall, that his face might not be seen; and the action was so delicate, and the man was so penetrated with repentance, and asked pardon so honestly, that he could make him no less acknowledgment than, 'I know you meant it kindly. Say no more.'

'Bless your soul, sir,' urged the Plasterer, 'I did indeed. I'd do more by you than the rest of 'em do, I fancy.'

'What would you do?' he asked.

'I'd come back to see you, after I was let out.'

'Give me the money again,' said the other, eagerly, 'and I'll keep it, and never spend it. Thank you for it, thank you! I shall see you again?'

'If I live a week you shall.'

They shook hands and parted. The collegians, assembled in Symposium in the Snuggery that night, marvelled what had happened to their Father; he walked so late in the shadows of the yard, and seemed so downcast."

Chapter 7 is title "The Child of the Marshalsea" and of course the child Little Dorrit, or Amy that is. Amy has been "handed down among the generations of collegians", the turnkey is even her godfather.

Chapter 7 is title "The Child of the Marshalsea" and of course the child Little Dorrit, or Amy that is. Amy has been "handed down among the generations of collegians", the turnkey is even her godfather."This invested the turnkey with a new proprietary share in the child, over and above his former official one. When she began to walk and talk, he became fond of her; bought a little arm-chair and stood it by the high fender of the lodge fire-place; liked to have her company when he was on the lock; and used to bribe her with cheap toys to come and talk to him. The child, for her part, soon grew so fond of the turnkey that she would come climbing up the lodge-steps of her own accord at all hours of the day. When she fell asleep in the little armchair by the high fender, the turnkey would cover her with his pocket-handkerchief; and when she sat in it dressing and undressing a doll which soon came to be unlike dolls on the other side of the lock, and to bear a horrible family resemblance to Mrs Bangham—he would contemplate her from the top of his stool with exceeding gentleness. "

The narrator tells us that in an early period of her childhood she comes to realize that it was not the habit of the rest of the world to live inside prison walls, walls with spikes at the top. She comes to realize that while she free to pass beyond the prison, her father must never cross that line. After she makes this discovery she begins to regard him with a pitiful and plaintive look. She also has the same pitiful and plaintive look for her wayward sister and her idle brother; for the high blank walls that are their home. After a conversation with the turnkey at the time asking him where the fields and meadows are, if they are pretty, and if they are locked up at night, the turnkey begins to take her out on walks every Sunday to see these fields and meadows. I like him for this.

"But this was the origin of a series of Sunday excursions that these two curious companions made together. They used to issue from the lodge on alternate Sunday afternoons with great gravity, bound for some meadows or green lanes that had been elaborately appointed by the turnkey in the course of the week; and there she picked grass and flowers to bring home, while he smoked his pipe. Afterwards, there were tea-gardens, shrimps, ale, and other delicacies; and then they would come back hand in hand, unless she was more than usually tired, and had fallen asleep on his shoulder."

After Amy's mother dies Amy takes on a new role in the family, taking care of them. At first she is so small that all she can do is sit with her father always keeping near him, by the time she is sixteen though she inspired to be something which was not what the rest were, for the sake of the family.

"No matter through what mistakes and discouragements, what ridicule (not unkindly meant, but deeply felt) of her youth and little figure, what humble consciousness of her own babyhood and want of strength, even in the matter of lifting and carrying; through how much weariness and hopelessness, and how many secret tears; she drudged on, until recognized as useful, even indispensable. That time came. She took the place of eldest of the three, in all things but precedence; was the head of the fallen family; and bore, in her own heart, its anxieties and shames.

At thirteen, she could read and keep accounts, that is, could put down in words and figures how much the bare necessaries that they wanted would cost, and how much less they had to buy them with. She had been, by snatches of a few weeks at a time, to an evening school outside, and got her sister and brother sent to day-schools by desultory starts, during three or four years. There was no instruction for any of them at home; but she knew well—no one better—that a man so broken as to be the Father of the Marshalsea, could be no father to his own children. "

Why he should be more broken than his children I don't know, or at least why he should be too broken to take care of his children I don't know. It is Amy though who takes care of them all, she asks a man also in the prison who is a dancing instructor to give her sister lessons, which being good natured and having a lot of time on his hands he agrees to do. She also asks a seamtress to teach her how to do needlework. Thanks to Amy eventually her sister becomes a dancer and now Amy goes out making money for her father by doing needlework. Then we also have her brother Tip to take care of, Tip is more of a challenge for Tip tries just about everything and ends up "cutting" just about everything. Through Little Dorrit's efforts Tip gets into;

"a warehouse, into a market garden, into the hop trade, into the law again, into an auctioneers, into a brewery, into a stockbroker's, into the law again, into a coach office, into a waggon office, into the law again, into a general dealer's, into a distillery, into the law again, into a wool house, into a dry goods house, into the Billingsgate trade, into the foreign fruit trade, and into the docks. But whatever Tip went into, he came out of tired, announcing that he had cut it. Wherever he went, this foredoomed Tip appeared to take the prison walls with him, and to set them up in such trade or calling; and to prowl about within their narrow limits in the old slip-shod, purposeless, down-at-heel way; until the real immovable Marshalsea walls asserted their fascination over him, and brought him back."

And through all this her father can't know for Amy thinks it would kill him. For we're told:

"In course of time, and in the very self-same course of time, the Father of the Marshalsea gradually developed a new flower of character. The more Fatherly he grew as to the Marshalsea, and the more dependent he became on the contributions of his changing family, the greater stand he made by his forlorn gentility. With the same hand that he pocketed a collegian's half-crown half an hour ago, he would wipe away the tears that streamed over his cheeks if any reference were made to his daughters' earning their bread. So, over and above other daily cares, the Child of the Marshalsea had always upon her the care of preserving the genteel fiction that they were all idle beggars together."

I don't like him at all, or Tip, or Fanny, or Mrs. Clennam, I'm starting to get the feeling I don't like anyone in the book. Except the turnkey and perhaps Amy.

Chapter 8 is titled "The Lock" and we find Arthur Clennam had followed Amy and is now waiting to ask someone passing by what building it is that she has entered. This got me wondering why he didn't know it was the Marshalsea. I know he has been gone for twenty years, but wouldn't you remember something as big and creepy (that's how I picture it) as a prison? So I went looking for a picture of it and it find out if it was there twenty years before our story begins and found this:

Chapter 8 is titled "The Lock" and we find Arthur Clennam had followed Amy and is now waiting to ask someone passing by what building it is that she has entered. This got me wondering why he didn't know it was the Marshalsea. I know he has been gone for twenty years, but wouldn't you remember something as big and creepy (that's how I picture it) as a prison? So I went looking for a picture of it and it find out if it was there twenty years before our story begins and found this:"The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, Surrey (now London), just south of the River Thames. It housed a variety of prisoners over the centuries, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, but it became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London's debtors. Over half the population of England's prisons in the 18th century were in jail because of debt.

Run privately for profit, as were all English prisons until the 19th century, the Marshalsea looked like an Oxbridge college and functioned as an extortion racket. Debtors in the 18th century who could afford the prison fees had access to a bar, shop and restaurant, and retained the crucial privilege of being allowed out during the day, which gave them a chance to earn money for their creditors. Everyone else was crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others, possibly for years for the most modest of debts, which increased as unpaid prison fees accumulated. The poorest faced starvation and, if they crossed the jailers, torture with skullcaps and thumbscrews. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten were dying every 24 hours in the warmer weather.

The prison became known around the world in the 19th century through the writing of the English novelist Charles Dickens, whose father was sent there in 1824, when Dickens was 12, for a debt to a baker. Forced as a result to leave school to work in a factory, Dickens based several of his characters on his experience, most notably Amy Dorrit, whose father is in the Marshalsea for debts so complex no one can fathom how to get him out."

I have more about the Marshalsea but I'll wait until later. I just don't understand how someone who grew up in a house within walking distance of the Marshalsea didn't know it was there. Anyway, Arthur waits and wonders until finally an old man comes walking by, he is described this way:

"He stooped a good deal, and plodded along in a slow pre-occupied manner, which made the bustling London thoroughfares no very safe resort for him. He was dirtily and meanly dressed, in a threadbare coat, once blue, reaching to his ankles and buttoned to his chin, where it vanished in the pale ghost of a velvet collar. A piece of red cloth with which that phantom had been stiffened in its lifetime was now laid bare, and poked itself up, at the back of the old man's neck, into a confusion of grey hair and rusty stock and buckle which altogether nearly poked his hat off. A greasy hat it was, and a napless; impending over his eyes, cracked and crumpled at the brim, and with a wisp of pocket-handkerchief dangling out below it. His trousers were so long and loose, and his shoes so clumsy and large, that he shuffled like an elephant; though how much of this was gait, and how much trailing cloth and leather, no one could have told. Under one arm he carried a limp and worn-out case, containing some wind instrument; in the same hand he had a pennyworth of snuff in a little packet of whitey-brown paper, from which he slowly comforted his poor blue old nose with a lengthened-out pinch, as Arthur Clennam looked at him."

Arthur stops him and finds that he is Frederick Dorrit, Amy's uncle and brother to the Father of the Marshalsea on his way to visit the family. He tells Arthur that anyone can go into the Marshalsea but not everyone can come out. Frederick asks Arthur to come in with him warning him first to say nothing to his brother about Amy working at her needle, we wouldn't want to hurt the Father of the Marshalsea's feelings after all. I didn't like Arthur going along inside, didn't he know how much that would embarrass Amy? But he does go along and finds that the food Amy is given every day for her lunch that no one sees her eat, she brings home for her father's meal. Arthur is introduced as a friend of Amy's who wants to pay his respects to Mr. Dorrit. Here are some of the things Arthur has to listen to because of his paying respects to the Father of the Marshalsea:

"'Mr Clennam,' returned the other, rising, taking his cap off in the flat of his hand, and so holding it, ready to put on again, 'you do me honour. You are welcome, sir;' with a low bow. 'Frederick, a chair. Pray sit down, Mr Clennam.'

He put his black cap on again as he had taken it off, and resumed his own seat. There was a wonderful air of benignity and patronage in his manner. These were the ceremonies with which he received the collegians.

'You are welcome to the Marshalsea, sir. I have welcomed many gentlemen to these walls. Perhaps you are aware—my daughter Amy may have mentioned that I am the Father of this place.'

'You could hardly have been here since your boyhood without my knowledge. It very seldom happens that anybody—of any pretensions—any pretensions—comes here without being presented to me.'

'As many as forty or fifty in a day have been introduced to my brother,' said Frederick, faintly lighting up with a ray of pride.

'Yes!' the Father of the Marshalsea assented. 'We have even exceeded that number. On a fine Sunday in term time, it is quite a Levee—quite a Levee."

Soon after this Tip and Fanny stop in, but we find it is only to pick up their clothing that Amy has "mended and made up" for them. They quickly leave since the bell is ringing which is the sign that visitors should leave and that the gates will soon be locked. Arthur, however, stays behind to say a few words to Little Dorrit telling her that he would like to be a friend to her, and ends up being locked inside the prison. He finds that Tip is also still inside the prison and Tip tells him that he is locked up for debts of his own but Amy doesn't want their father to know. Arthur ends up spending the night on two tables that are put together to make a bed in the Snuggery, a tavern like establishment at the upper end of the prison. I didn't know prisons had taverns in them. The chapter ends this way:

" What if his mother had an old reason she well knew for softening to this poor girl! What if the prisoner now sleeping quietly—Heaven grant it!—by the light of the great Day of judgment should trace back his fall to her. What if any act of hers and of his father's, should have even remotely brought the grey heads of those two brothers so low!

A swift thought shot into his mind. In that long imprisonment here, and in her own long confinement to her room, did his mother find a balance to be struck? 'I admit that I was accessory to that man's captivity. I have suffered for it in kind. He has decayed in his prison: I in mine. I have paid the penalty.'

When all the other thoughts had faded out, this one held possession of him. When he fell asleep, she came before him in her wheeled chair, warding him off with this justification. When he awoke, and sprang up causelessly frightened, the words were in his ears, as if her voice had slowly spoken them at his pillow, to break his rest: 'He withers away in his prison; I wither away in mine; inexorable justice is done; what do I owe on this score!'

Ok, here's my more about the Marshalsea:

Ok, here's my more about the Marshalsea:"Southwark was settled by the Romans around 43 CE. It served as an entry point into London from southern England, particularly along Watling Street, the Roman road from Canterbury; this ran into what is now Southwark's Borough High Street and from there north to old London Bridge. The area became known for its travellers and inns, including Geoffrey Chaucer's Tabard Inn. The itinerant population brought with it poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres (including Shakespeare's Globe) and, inevitably, prisons. In 1796 there were five prisons in Southwark – the Clink, King's Bench, Borough Compter, White Lion and the Marshalsea – compared to 18 in London as a whole.

Until the 19th century imprisonment was not viewed as a punishment in itself in England, except for minor offences such as vagrancy. Prisons simply held people until their creditors had been paid or their fate decided by judges; options included execution (ended 1964), flogging (1962), the stocks (1872), the pillory (1830), the ducking stool (1817), joining the military, or penal transportation to America or Australia (1867). In 1774 there were just over 4,000 prisoners in Britain, half of them debtors, out of a population of six million.

Prisoners had to pay rent, feed and clothe themselves and, in the larger prisons, furnish their rooms. One man found not guilty at trial in 1669 was not released because he owed prison fees from his pre-trial confinement, a position supported by the judge, Matthew Hale. Jailers sold food or let out space for others to open shops; the Marshalsea contained several shops and small restaurants. Prisoners with no money or external support faced starvation. If the prison did supply food to its non-paying inmates, it was purchased with charitable donations – donations sometimes siphoned off by the jailers – usually bread and water with a small amount of meat, or something confiscated from elsewhere as unfit for human consumption. Jailers would load prisoners with fetters and other iron, then charge for their removal, known as "easement of irons" (or "choice of irons"); this became known as the "trade of chains."

The Marshalsea occupied two buildings on the same street in Southwark. The first dated back to the 14th century at what would now be 161 Borough High Street, between King Street and Mermaid Court. By the late 16th century the building was crumbling. In 1799 the government reported that it would be rebuilt 130 yards (119 m) south on what is now 211 Borough High Street. Most of the first Marshalsea, as with the second, was taken up by debtors; in 1773 debtors within 12 miles of Westminster could be imprisoned there for a debt of 40 shillings. Jerry White writes that London's poorest debtors were housed in the Marshalsea. Wealthier debtors arranged to be moved –regularly securing their removal from the Marshalsea by writ of habeas corpus –to the Fleet or the King's Bench, both of which were more comfortable. The prison also held a small number of men being tried at the Old Bailey for crimes at sea.

By the 18th century, the prison had separate areas for its two classes of prisoner: the master's side, which housed about 50 rooms for rent, and the common or poor side, consisting of nine small rooms, or wards, into which 300 people were confined from dusk until dawn. Room rents on the master's side were ten shillings a week in 1728, with most prisoners forced to share. Women prisoners who could pay the fees were housed in the women's quarters, known as the oak. The wives, daughters and lovers of male prisoners were allowed to live with them, if someone was paying their way.

Known as the castle by inmates, the prison had a turreted lodge at the entrance, with a side room called the pound, where new prisoners would wait until a room was found for them. The front lodge led to a courtyard known as the park. This had been divided in two by a long narrow wall, so that prisoners from the common side could not be seen by those on the master's side, who preferred not to be distressed by the sight of abject poverty, especially when they might themselves be plunged into it at any moment.

There was a bar run by the governor's wife, and a chandler's shop run in 1728 by a Mr and Mrs Cary, both prisoners, which sold candles, soap and a little food. There was a coffee shop run in 1729 by a long-term prisoner, Sarah Bradshaw, and a steak house called Titty Doll's run by another prisoner, Richard McDonnell, and his wife. There was also a tailor and a barber, and prisoners from the master's side could hire prisoners from the common side to act as their servants.

By all accounts, living conditions in the common side were horrific. In 1639 prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without space to lie down, leading to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a "bull's pizzle" (a whip made from a bull's penis), or tortured with thumbscrews and a skullcap, a vice for the head that weighed 12 lb (5.4 kg).

What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the strong room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadavers awaiting burial and piles of night soil. Dickens described it as, "dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats." One apparently diabetic army officer who died in the strong room – he had been ejected from the common side because inmates had complained about the smell of his urine – had his face eaten by rats within hours of his death, according to a witness.

By 1799 Marshalsea had fallen into a state of decay, and a decision was made to rebuild it 130 yards south. Like the first Marshalsea, the second was notoriously cramped. In 1827, 414 out of its 630 debtors were there for debts under £20; 1,890 people in Southwark were imprisoned that year for a total debt of £16,442. Women debtors were housed in rooms over the tap room. The rooms in the barracks (the men's rooms) were 10 ft. 10 ins (3.3 m) square and 8–9 ft (2.4–2.7 m) high, with a window, wooden floors and a fireplace. Each housed two or three prisoners, and as the rooms were too small for two beds, prisoners had to share. Apart from the bed, prisoners were expected to provide their own furniture. An anonymous witness complained in 1833: "170 persons have been confined at one time within these walls, making an average of more than four persons in each room – which are not ten feet square!!! I will leave the reader to imagine what the situation of men, thus confined, particularly in the summer months, must be

Much of the prison business was run by a debtors' committee of nine prisoners and a chair (a position held by Dickens' father). The committee was responsible for imposing fines for rules violations, an obligation they met with enthusiasm. Debtors could be fined for theft; throwing water or filth out of windows or into someone else's room; making noise after midnight; cursing, fighting or singing obscene songs; smoking in the beer room 8–10p. am or 12–2p. pm; defacing the staircase; dirtying the privy seats; stealing newspapers or utensils from the snuggery; urinating in the yard; drawing water before it had boiled; and criticizing the committee.

As dreadful as the Marshalsea could be, it could also be a haven, because it kept the creditors away. Debtors could even arrange to have themselves arrested by a business partner to enter the jail when it suited them. Historian Margot Finn writes that discharge could therefore be used as a punishment; one debtor was thrown out in May 1801 for "making a Noise and disturbance in the prison."

"Trey Philpotts (whoever that is) writes that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s.According to Philpotts, Dickens rarely made mistakes and did not exaggerate; if anything, he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities."

Kim

KimOh, my. Thank you for your research into the Marshalsea prison. While I did know it by name, and as the place of Dickens's father's imprisonment (as well as the rest of his family) I never looked any further into it.

I need to catch my breath and go back and re-read chapters 6,7 and 8 again.

What strikes me most is the fact that while a high percentage of the people imprisoned in the Marshalsea were there for debt, it appears that one of the only ways one could survive there was by purchasing items to keep you fed and alive. I realize that while "outsiders" like little Charles Dickens could bring money and comforts to those incarcerated, it still strikes me as incredibly ironic that one would be in jail for debt but could only survive in jail through the exchange of money. A strange world indeed.

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,Welcome to the second installment of many, many installments with many, many characters being introduced, some I find quite unlikeable. The first chapter for this installment is..."

Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line to include in one of the quotations Kim. Pure Dickens.

I think those lines could also be seen in a broader context. There is much that is hidden in this dilapidated house. What is there, or is there a secret being kept from Arthur. Well, it's Dickens. Of course there must be a secret. Can it have anything to do with Arthur's watch? Is the secret in any way connected to time?

The Clennam's are a very dysfunctional family. Money seems to be one of the roots of this dysfunction. Certainly money will be a motif in the novel. The Marshalsea Prison is a monument to money, or the lack of it.

Secrets. Little Dorrit is so secretive. It was a bit unnerving to watch Arthur Clennam stalking her through the streets of London. While his motivations and intentions were honourable, I found his slinking about unsettling. I think Dickens must be preparing the reader for much more of Arthur's lurking and slinking as he tries to unravel the secrets of his own home and the world of the Marshalsea.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 6 is titled "The Father of the Marshalsea", and we find that this Father is Little Dorrit's father. The chapter opens with this description of the Marshalsea:

Kim wrote: "Chapter 6 is titled "The Father of the Marshalsea", and we find that this Father is Little Dorrit's father. The chapter opens with this description of the Marshalsea:"Thirty years ago there stood..."

I enjoyed your phrase that while Dorrit may be locked in his worries are locked out. The prison is portrayed as a rather pleasant place, and we read that Dorrit "languidly slipped into this smooth descent." In time Dorrit becomes the longest serving inmate, which is seen as a position of prestige. Dickens develops this topsy-turvy world in such a manner that it is an honour to be in jail for an extended period of time. Indeed, people pay homage to that very fact. If Queen Victoria was the head of state then why not have a reigning head of the Marshalsea?

Hidden secrets, a world of expectations in life turned upside down. We have families of some substance like the Clennams living in a crumbling home while a family in poverty assumes the titular mantle of respectability in a solidly built debtor's jail. The Clennam family is like their house; it is weak, leaning and broken while the Dorrit family, who lives in the jail, is solid, firm and weirdly functional. Tip may live on the "shady side of the street," but he still functions within the Dorrit family's dynamics.

Kim, I'm much obliged to you for all the information you gathered on the Marshalsea - of course, a debtors' prison is something the avid Dickens reader will frequently come across, but there are also some scenes in Roderick Ransom that play in a debtors' prison (I don't know whether it is the Marshalsea or not). By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ages.

Kim, I'm much obliged to you for all the information you gathered on the Marshalsea - of course, a debtors' prison is something the avid Dickens reader will frequently come across, but there are also some scenes in Roderick Ransom that play in a debtors' prison (I don't know whether it is the Marshalsea or not). By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ages.Which brings me on to something that does not have anything at all to do with a debtors' prison but that is nice to know or hear about, I think: In Birthälm, Transsylvania, the castle had a special cell where they locked up married couples that had quarrelled and were completely at odds with each other. In that cell, there was only one bed, one table, one chair, one plate, one beaker and one spoon - all of which the quarrelling couple had to share, and they were not set free before they had made up their quarrel or vowed not to fall out with each other again.

Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy Dorrit - not as a character, but as a literary creation. Once again, we have the self-denying, eager-to-please, submissive young woman, who - in Amy's case - even looks more like a child than like a woman (I'm afraid of Little Nell's coming from her grave), and who is surrounded by a rather egocentric family. It is easy, all too easy to foresee where this is going to lead us, isn't it?

Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy Dorrit - not as a character, but as a literary creation. Once again, we have the self-denying, eager-to-please, submissive young woman, who - in Amy's case - even looks more like a child than like a woman (I'm afraid of Little Nell's coming from her grave), and who is surrounded by a rather egocentric family. It is easy, all too easy to foresee where this is going to lead us, isn't it?Besides, I find Dickens's penchant for the unoffending, self-sacrificing heroine quite annoying. I wish there were one female heroine a bit more interesting and life-like, with some rough edges - like e.g. Sylvia in Sylvia's Lovers, but Dickens simply does not seem to have had any grasp at creating this kind of heroine.

What I find extremely fascinating about Little Dorrit, in contrast to its uninteresting heroine, is the way Dickens is telling his story. Last week I already mentioned the clever way in which we are given background information on the characters in Chapters 2 and also 1, as well as the unusual introduction of Little Dorrit herself. What I noticed about Chapters 6 and 7 is that Dickens leaps between the time levels, taking us back into the past and then jumping between the relative present and the past. For example, we are told that the turnkey is getting older and finally no longer sits at the lodge, but later we are told how he is taking Amy out to visit meadows and fields.

What I find extremely fascinating about Little Dorrit, in contrast to its uninteresting heroine, is the way Dickens is telling his story. Last week I already mentioned the clever way in which we are given background information on the characters in Chapters 2 and also 1, as well as the unusual introduction of Little Dorrit herself. What I noticed about Chapters 6 and 7 is that Dickens leaps between the time levels, taking us back into the past and then jumping between the relative present and the past. For example, we are told that the turnkey is getting older and finally no longer sits at the lodge, but later we are told how he is taking Amy out to visit meadows and fields.This is a rather modern way of telling a story, I'd say, breaking up the strict, and often dull, chronological order. Bravo, Dickens!

Tristram wrote: "Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy D..."

Tristram wrote: "Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy D..."I knew it!!! I knew as soon as I saw how sweet and good and kind and of course little, Amy Dorrit was you would hate her. Poor, poor little Amy is struggling to support her entire family and here you are picking on her already. Who knows, perhaps we will have another one of those touching death bed scenes like we had with little Nell you so enjoyed. (So far I don't like her much either but I'm not telling you that.)

I'm off to look at German prisons and castles with marriage cells. I guess I'll get the illustrations first.

It's quite ironic to invent such a thing as a marriage cell, isn't it? In King Vidor's "The Crowd", a fine silent movie, one of the characters says, "Marriage is not a word ... it's a sentence."

It's quite ironic to invent such a thing as a marriage cell, isn't it? In King Vidor's "The Crowd", a fine silent movie, one of the characters says, "Marriage is not a word ... it's a sentence."

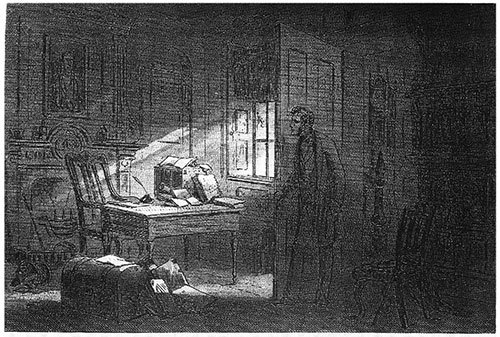

Mr. Flintwich mediates as a friend of the family

Book I, Chapter 5

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

Commentary:

"An example of the effective pairing of a normal with a dark plate. "Mr. Flintwinch mediates as a friend of the Family," (Bk 1, ch. 5) again, is elaborately etched, with all three faces modeled and the background fully filled in. Mr. Flintwinch's face is the most striking, done with a modified caricature technique which conveys the man's grotesqueness without that impossibility of face one sometimes got in Browne's early work. An emblematic detail appears, done with extreme care in the working drawing as well as the etching, which may at first seem out of place in the mode Browne establishes in these first few illustrations, where tone and composition seem to matter more than minor detail. It is a picture over Flintwinch's head, identifiable as the central portion of John Martin's painting and mezzotint, Joshua Commanding the Sun to standstill on Gibeon, probably the most familiar image of this episode in the first half of the century, especially in woodcut illustrations of the Bible (see William Feaver). The presence of such a picture in the room of Mrs. Clennam, an extreme self-justifying Calvinist, is plausible. In Dickens' words, Mrs. Clennam has "a general impression" that threatening to disown her son "was in some sort a religious proceeding". Jeremiah's first name also fits well with his function as mediator, speaking for the lordly Mrs. Clennam to the sinful Arthur. In the detail, Joshua's hand is raised in the same way as Flintwinch's, and there is a visual pun: the (supposed) man of God causes the "son" to stand still, to cease his rebellion."

Good luck seeing all that, I can barely see the painting at all.

The Room with the Portrait

Book I, Chapter 5

Phiz

Commentary:

"The Room with the Portrait" (Bk 1, ch. 5) is a pendant to the episode in the preceding plate, as Arthur goes to his late father's room and sees the portrait of the dead man "with the eves intently looking at his son as they had looked when life departed from them," and which "seemed to urge him awfully to the task he had attempted". The darker of the duplicate plates goes rather far in the direction of obscurity, and many readers may prefer the lighter one with more distinct details, yet the darkness of Arthur's face in the murkier plate more effectively expresses the fact that Arthur himself is becoming engulfed in a darkness of mind and spirit. The illustration as a whole is a successful follow-up to its companion, representing the unremitting darkness Arthur has found in the bosom of his family, and his sense of helplessness against it. It also again suggests the novel's central image, the prison — literally the enclosed space and psychologically the identity from which one cannot escape as Mr. Dorrit never escapes his prisoner role, and as Clennam feels trapped in the joyless Puritan acquisitiveness of his family."

Tristram wrote: "By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ages."

Tristram wrote: "By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ages."Look! Here it is!!

This place is amazing, I can't believe it is a church, I'd love to go to church here. Marriage cell and all.

This place is amazing, I can't believe it is a church, I'd love to go to church here. Marriage cell and all.Biertan Fortified Church

Tristram wrote: "Kim, I'm much obliged to you for all the information you gathered on the Marshalsea - of course, a debtors' prison is something the avid Dickens reader will frequently come across, but there are al..."

Tristram wrote: "Kim, I'm much obliged to you for all the information you gathered on the Marshalsea - of course, a debtors' prison is something the avid Dickens reader will frequently come across, but there are al..."Must have been much cheaper than marriage counselling.

Tristram wrote: "Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy D..."

Tristram wrote: "Little Dorrit, as most of Dickens's novels, shows that in Dickens's case, his weak points and his strengths lay very close together: I must frankly confess that I heartily and utterly dislike Amy D..."I hesitate to say I really like the character of Little Dorrit so I'll say she is a little on the vapid side, but it is early in the story. Then again, how many times does Dickens really do major alterations to a female character as his novel evolves?

We must accept that Dickens will not ever give us a Lydia Gwilt. To date, is Dickens most interesting female Edith Dombey?

Kim wrote: "The Room with the Portrait

Kim wrote: "The Room with the PortraitBook I, Chapter 5

Phiz

Commentary:

"The Room with the Portrait" (Bk 1, ch. 5) is a pendant to the episode in the preceding plate, as Arthur goes to his late father's ..."

Thanks, as always Kim.

The explanations for the illustrations seem logical and persuasive, but how anyone can tell what the picture is above Flintwinch's head is beyond me. I like "The Room with the Portrait" very much. The house is like a prison, and Arthur is a prisoner both psychologically and physically.

Peter wrote: "The explanations for the illustrations seem logical and persuasive, but how anyone can tell what the picture is above Flintwinch's head is beyond me."

Peter wrote: "The explanations for the illustrations seem logical and persuasive, but how anyone can tell what the picture is above Flintwinch's head is beyond me."Here's the painting, I'll take their word for it that it's on the wall behind Flintwinch.

Overview

"In this epic, densely populated work, John Martin depicts the biblical battle at Gibeon, part of the conquest of Canaan. Joshua, as leader of the Israelites, asks God to cause the moon and the sun to stand still so that he and his army might continue fighting by daylight. God further assists Joshua by calling up a powerful storm to bombard the Canaanites with rain and hailstones. Following this battle, Joshua led the Israelites to several more victories, ultimately conquering much of Canaan. Martin combines the genres of history and landscape painting in this work by giving equal compositional space and artistic attention to both the human narrative and the dramatic natural surroundings.

John Martin (19 July 1789 – 17 February 1854) was an English Romantic painter, engraver and illustrator. He was celebrated for his typically vast and melodramatic paintings of religious subjects and fantastic compositions, populated with minute figures placed in imposing landscapes. Martin's paintings, and the engravings made from them, enjoyed great success with the general public—in 1821 Lawrence referred to him as "the most popular painter of his day"—but were lambasted by Ruskin and other critics.

Martin was passionate, a devotee of chess—and, in common with his brothers, swordsmanship and javelin-throwing—and a devout Christian, believing in "natural religion". Despite an often cited singular instance of his hissing at the national anthem, he was courted by royalty and presented with several gold medals, one of them from the Russian Tsar Nicholas, on whom a visit to Wallsend colliery on Tyneside had made an unforgettable impression: "My God," he had cried, "it is like the mouth of Hell." Martin became the official historical painter to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, later the first King of Belgium. Leopold was the godfather of Martin's son Leopold, and endowed Martin with the Order of Leopold. Martin frequently had early morning visits from another Saxe-Coburg, Prince Albert, who would engage him in banter from his horse—Martin standing in the doorway still in his dressing gown—at seven o'clock in the morning. Martin was defender of deism and natural religion, evolution (before Darwin) and rationality. Georges Cuvier became an admirer of Martin's, and he increasingly enjoyed the company of scientists, artists and writers—Dickens, Faraday and Turner among them."

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "The explanations for the illustrations seem logical and persuasive, but how anyone can tell what the picture is above Flintwinch's head is beyond me."

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "The explanations for the illustrations seem logical and persuasive, but how anyone can tell what the picture is above Flintwinch's head is beyond me."Here's the painting, I'll take ..."

Well ... OK, I guess. It still seems far-fetched to me, but no doubt some of my comments on the novels may seem far-fetched too. :-))

Kim wrote: "The Room with the Portrait

Kim wrote: "The Room with the PortraitBook I, Chapter 5

Phiz

Commentary:

"The Room with the Portrait" (Bk 1, ch. 5) is a pendant to the episode in the preceding plate, as Arthur goes to his late father's ..."

Wonderful, Kim: I love those dark plates, I already did so with Bleak House, but then I love film noir, esp. when it is made in the studio - for its hauntingly claustrophobic effects. Phiz would not have been able to do justice to the Clennam house without using dark plates, I think, because the Mrs. Clennam chapters are so very brooding and stifling, and you can really feel with Arthur when you look at the second picture.

As to identifying the painting in the first plate, well, it could be anything, if you ask me. It could be a dustheap, a haystack being climbed by Gabrial Oak, it could even be a dunghill in front of a Westphalian farmer's house - they used to display their dunghills as a sign of wealth and prosperity.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ag..."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the way, debtors' prisons also existed in Germany, and in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) you can still see a "Schuldturm", i.e. a tower where they used to lock up debtors in the Middle Ag..."If you ever visit Germany, you should go to see Nürnberg. It's a must, especially for Christmas Market Lovers.

Kim wrote: "This place is amazing, I can't believe it is a church, I'd love to go to church here. Marriage cell and all.

Kim wrote: "This place is amazing, I can't believe it is a church, I'd love to go to church here. Marriage cell and all.Biertan Fortified Church

"

I actually stayed at that church for about two weeks more than twenty years ago. It was, and maybe still is, some kind of hotel, and since my grandmother hails from Transsylvania, I took the chance offered by two of my History professors at the university to go there and learn more about the Siebenbürger Sachsen. The Carpathian forests, the old towns and Kirchenburgen, it was all like a fairy tale.

I keep coming back to the portrayal of Little Dorrit. We are told that she is in her early twenties and told that she looks only half her age and are obviously told she is little. The child-adult. And yet I do not feel her innocence for some strange reason.

I keep coming back to the portrayal of Little Dorrit. We are told that she is in her early twenties and told that she looks only half her age and are obviously told she is little. The child-adult. And yet I do not feel her innocence for some strange reason.Then, on the Clennam side of the novel, we have Arthur coming back home to a dark, crumbly place, with a rather strange social situation within his prison-like home. We have the ever-present prisons of both France and England taking centre stage in the novel.

Is it me, or does this novel have a great deal of gothic undertones?

So far, the novel has a sinister edge, an unpleasant taste, an eerie uncomfortable feel. It's Dickens, but a very much darker Dickens than all the smoke in Coketown could ever produce.

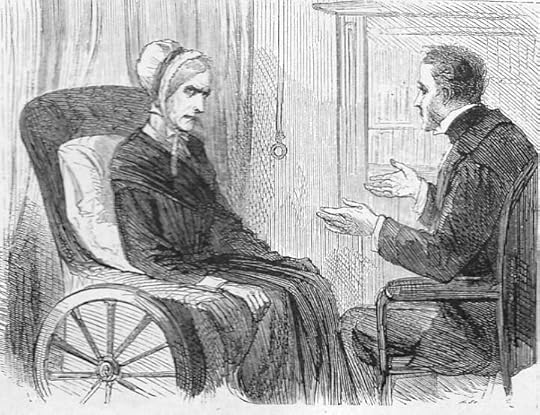

More illustrations, the first by Sol Eytinge Jr.

More illustrations, the first by Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam"

The third full-page illustration by Sol Eytinge, Jr. for the Diamond Edition of Dickens's Little Dorrit, 1871

Commentary: (wow, I'm glad I read this before posting it, there was a major spoiler in here, but don't worry, I've cut it out.)

"The third paired character study to complement Dickens's narrative, Eytinge's "Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam," focuses on the dictatorial invalid, her wheel-chair almost a throne in that it and she together dominate the picture. Missing from the illustration, although very much present in the facing page of the text, is the butler, Flintwinch. Accordingly, the reader of 1871 would probably have connected this earlier passage from Chapter Five, "Family Affairs," with Eytinge's third full-page illustration:

Looking at him wrathfully, she bent herself back in her chair to keep him further off, but gave him no reply.

"I am deeply sensible, mother, that if this thought has never at any time flashed upon you, it must seem cruel and unnatural in me, even in this confidence, to breathe it. But I cannot shake it off. Time and change (I have tried both before breaking silence) do nothing to wear it out. Remember, I was with my father. Remember, I saw his face when he gave the watch into my keeping, and struggled to express that he sent it as a token you would understand, to you. Remember, I saw him at the last with the pencil in his failing hand, trying to write some word for you to read, but to which he could give no shape. The more remote and cruel this vague suspicion that I have, the stronger the circumstances that could give it any semblance of probability to me. For Heaven's sake, let us examine sacredly whether there is any wrong entrusted to us to set right. No one can help towards it, mother, but you.

"Still so recoiling in her chair that her over poised weight moved it, from time to time, a little on its wheels, and gave her the appearance of a phantom of fierce aspect gliding away from him, she interposed her left arm, bent at the elbow with the back of her hand towards her face, between herself and him, and looked at him in a fixed silence.

Eytinge effectively communicates the essentials of Mrs. Clennam's character: her inflexible nature, her moral rigidity, her stern Calvinist approach to life, and especially her lack of warm and maternal feeling for her son."

This one is by James Mahoney:

This one is by James Mahoney:

Book 1, Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Text illustrated:

"They looked tempting; eight in number, circularly set out on a white plate, on a tray covered with a white napkin, flanked by a slice of buttered french roll and a little compact glass of cool wine and water"—Book 1, chap. v.

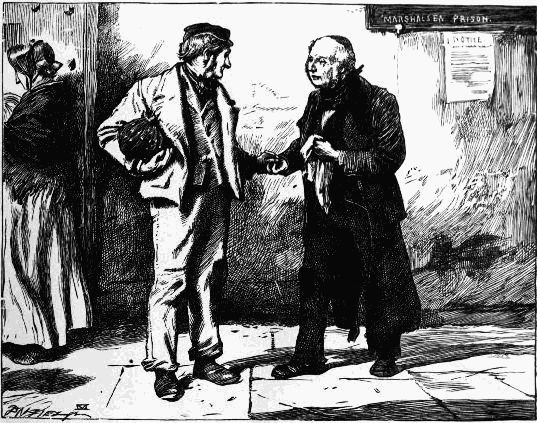

Another by James Mahoney for awhile I was baffled as to what it was.

Another by James Mahoney for awhile I was baffled as to what it was.

"Give me the money again," said the other eagerly, "And I'll keep it and never spend it"—Book 1, chap. 6

James Mahoney

Kim wrote: "Well, I'm sitting here reading this and thinking; "Good for you Arthur! I'm glad to know you haven't become what your mother has, at least you don't seem to be anything like her at this point." ."

Kim wrote: "Well, I'm sitting here reading this and thinking; "Good for you Arthur! I'm glad to know you haven't become what your mother has, at least you don't seem to be anything like her at this point." ."And I'm sitting here thinking "you little twit. Here your mother has been keeping this business alive for your father and then for your, keeping herself alive for your sake, and almost as soon as you get home you tell her, effectively, "go stuff yourself. I don't care what you did for me, I'm out'a here, I don't even want to live in the same house with you." No kindness, no consideration, no recognition of appreciation for carrying him in her body for 9 months and giving birth to him in the pain of Victorian childbirth. Nope.

She would have been much better off if he'd never come home.

Kim wrote: "Amy's father is described as a very amiable and very helpless middle-aged gentleman,."

Kim wrote: "Amy's father is described as a very amiable and very helpless middle-aged gentleman,."Amy's father is a greedy and manipulative man who is quite happy living a life of leisure on the backs of others, including his daughter. In the language of the 1980s, he's a Welfare King.

Kim wrote: "After Amy's mother dies Amy takes on a new role in the family, taking care of them."

Kim wrote: "After Amy's mother dies Amy takes on a new role in the family, taking care of them."Does anybody really believe in Amy as even remotely realistic? Is it possible to conceive a flesh and blood person turning out the way she did given the environment she was brought up in? There must have been some very strong woman as examples for her who we don't hear about. Certainly Mrs. Bangham wasn't it. She doesn't, as far as we see, ever attend church or school or have any constructive adult relationships. Realistically, how is it possible for her to turn out as she did?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 8 is titled "The Lock" and we find Arthur Clennam had followed Amy."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 8 is titled "The Lock" and we find Arthur Clennam had followed Amy."Today, wouldn't we call him a stalker? Or at least something weird and suspicious? Would you want your daughter's employer's newly arrive son spying on her, following her home, asking strangers on the street where she lived? There's something not right about this.

Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "

Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "Great minds think alike. (As so, apparently, does Kim's.) I had marked this passage in my book with the note that only Dickens could write a line like this. I like the whole line:

The furniture, at once spare and lumbering, hid in the rooms rather than furnished them, and there was no colour in all the house; such colour as had ever been there, had long ago started away on lost sunbeams—got itself absorbed, perhaps, into flowers, butterflies, plumage of birds, precious stones, what not.

What other author has ever imagined the color in a room being lost on sunbeams or aborbed into butterflies. Amazing writing.

Peter wrote: "We have families of some substance like the Clennams living in a crumbling home while a family in poverty assumes the titular mantle of respectability in a solidly built debtor's jail. ."

Peter wrote: "We have families of some substance like the Clennams living in a crumbling home while a family in poverty assumes the titular mantle of respectability in a solidly built debtor's jail. ."Yes, this continues the theme of the opening chapters of prisons. Mrs. Clennam is certainly in prison as much as Mr. Dorrit is, or indeed as much as Arthur was back in Marseilles.

But while Amy accepts the responsibility of living in her father's prison with him, Arthur rejects the responsibility of living in his mother's prison with her. He would rather live in a pub than have anything to do with the invalid woman who gave him life.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "Great minds think alike. (As so, apparently, does Kim's.) I had marked this passage in my bo..."

His writing is truly amazing. I am always surprised when I come across passages that on an earlier reading I missed, skipped over or whatever and then bang there are the words formed like no one else could ever do. Where was my mind the time(s) before?

Another passage I loved:

Another passage I loved:Hence the smugglers habitually consorted with the debtors (who received them with open arms), except at certain constitutional moments when somebody came from some Office, to go through some form of overlooking something which neither he nor anybody else knew anything about. On these truly British occasions, the smugglers, if any, made a feint of walking into the strong cells and the blind alley, while this somebody pretended to do his something: and made a reality of walking out again as soon as he hadn't done it—neatly epitomising the administration of most of the public affairs in our right little, tight little, island.

Since had been a Parliamentary reporter, he knew more about the workings of the British government than most people.

For someone who might know something about this book but doesn't want to intrude a spoiler, I'll just say that we might hear something more about this style of government before long.

Everyman wrote: "Does anybody really believe in Amy as even remotely realistic?"

Everyman wrote: "Does anybody really believe in Amy as even remotely realistic?"Oddly enough, I think she's one of the most realistic characters Dickens has depicted. The gender doesn't matter; when you're born into a particularly isolated world with little comparison outside its walls, you make of it what you can and you love and respect the people who tell you to love and respect them.

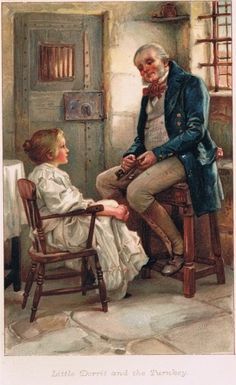

An illustration by Arthur A. Dixon

An illustration by Arthur A. Dixon

"Little Dorrit and the Turnkey"

" Little Amy Dorrit was born in the Marshalsea, where her father, William, is imprisoned for debt. Amy is resourceful and hardworking, managing the family’s meager finances and caring for her father. She is seen here with the prison turnkey."

Child Characters from Dickens. Illustrated by Arthur A. Dixon.

First edition 1905

Peter wrote: "So far, the novel has a sinister edge, an unpleasant taste, an eerie uncomfortable feel. It's Dickens, but a very much darker Dickens than all the smoke in Coketown could ever produce. "

Peter wrote: "So far, the novel has a sinister edge, an unpleasant taste, an eerie uncomfortable feel. It's Dickens, but a very much darker Dickens than all the smoke in Coketown could ever produce. "Exactly, Peter, and I hope it is going to remain that sinister and eeriely uncomfortable!

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Well, I'm sitting here reading this and thinking; "Good for you Arthur! I'm glad to know you haven't become what your mother has, at least you don't seem to be anything like her at this..."

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Well, I'm sitting here reading this and thinking; "Good for you Arthur! I'm glad to know you haven't become what your mother has, at least you don't seem to be anything like her at this..."Well, yes, and no.

Yes, because I think that Arthur's decision to quit the family business is rash in that it is partly based on the mere assumption of something being wrong there, of his parents having wronged somebody, and he does not want to have anything to do with it. This suspicion is solely based on his father's behaviour on his deathbed but there is no concrete evidence whatsoever - and on seeing Amy Dorrit, Arthur somehow comes to link his suspicion with the Dorrit family. You could call this an idée fixe and wonder why this whim can take so obsessive a hold on Arthur. On the other hand, Arthur says that the business, like the house, has fallen out of time and is probably not going so well anymore, and why should he invest his time and money in it when there might be a more rewarding course of action?

As to the necessary gratefulness to his mother: She does not seem overly welcoming, either, and she has probably given him a hell of a childhood with her austere ways. Carrying a baby for 9 months is definitely something you ought to be grateful for, but on the other hand nobody was ever asked if they wanted to be carried and borne into this life, and if a mother does not show any love for her child, maybe there is a limit of filial obligation.

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "After Amy's mother dies Amy takes on a new role in the family, taking care of them."

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "After Amy's mother dies Amy takes on a new role in the family, taking care of them."Does anybody really believe in Amy as even remotely realistic? Is it possible to conceive a flesh a..."

That is exactly how I feel about her, about Little Nell and about Oliver Twist!

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Furniture that "hid in the rooms rather than furnished them." what a great Dickens line "Great minds think alike. (As so, apparently, does Kim's.) I had marked this..."

And then there is so much of this kind of writing that it is impossible to take it in completely in the first reading.

Kim wrote: "An illustration by Arthur A. Dixon

Kim wrote: "An illustration by Arthur A. Dixon"Little Dorrit and the Turnkey"

" Little Amy Dorrit was born in the Marshalsea, where her father, William, is imprisoned for debt. Amy is resourceful and hardwo..."

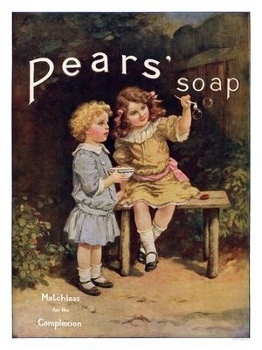

If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration.

Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."

Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."Oh Peter, I never heard of Pears soap, that I remember anyway, but I just couldn't resist this opportunity:

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."Oh Peter, I never heard of ..."

An eerie resemblance. I well remember that when my parents had company out would come the bar of Pears' soap. Then, when they left, the soap disappeared until the next company arrived.

What happened if people just dropped by for a visit I cannot remember. :-))

Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."

Peter wrote: "If it was not for the bars on the door and window this illustration would be a 19C Pears soap advertisement. Little Dorrit is eerie in this illustration."And also a lot plumper than I would have thought -- where did they get the money for that much food?

Kim wrote: "Oh Peter, I never heard of Pears soap, that I remember anyway, "

Kim wrote: "Oh Peter, I never heard of Pears soap, that I remember anyway, "I was brought up on Pears soap. Except when at the cottage in Maine, when it was Ivory soap because it floated, and the lake was our bathtub so we needed a soap that would float.

Welcome to the second installment of many, many installments with many, many characters being introduced, some I find quite unlikeable. The first chapter for this installment is Chapter 5 titled "Family Affairs" and begins we're told on Monday morning as the clocks struck nine. Jeremiah Flintwinch has just wheeled Mrs. Clennam to her desk when Arthur arrives. He asks if she is feeling better and she replies that she never will be better but she knows it and can bear it. She tells Arthur that she has been waiting for over a year for him to come home, that she has wanted to talk about the business with him ever since his father died. Arthur tells his mother that he plans to leave the business:

'You have anticipated, mother, that I decide for my part, to abandon the business. I have done with it. I will not take upon myself to advise you; you will continue it, I see. If I had any influence with you, I would simply use it to soften your judgment of me in causing you this disappointment: to represent to you that I have lived the half of a long term of life, and have never before set my own will against yours. I cannot say that I have been able to conform myself, in heart and spirit, to your rules; I cannot say that I believe my forty years have been profitable or pleasant to myself, or any one; but I have habitually submitted, and I only ask you to remember it.'

I'm not sure why but I have a very hard time picturing Arthur as being a forty year old man, I can only see him as a young man, perhaps in his twenties in my mind. Mrs. Clennam's reaction to this made me hope there are not many Christians out there who are like this woman is:

"Woe to the suppliant, if such a one there were or ever had been, who had any concession to look for in the inexorable face at the cabinet. Woe to the defaulter whose appeal lay to the tribunal where those severe eyes presided. Great need had the rigid woman of her mystical religion, veiled in gloom and darkness, with lightnings of cursing, vengeance, and destruction, flashing through the sable clouds. Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors, was a prayer too poor in spirit for her. Smite Thou my debtors, Lord, wither them, crush them; do Thou as I would do, and Thou shalt have my worship: this was the impious tower of stone she built up to scale Heaven. "

Arthur then tells her he wants to ask her about something that has been on his mind for a long time. Arthur believes that his father may have had some secret remembrance which caused him trouble, that somehow he had wronged someone:

'I am deeply sensible, mother, that if this thought has never at any time flashed upon you, it must seem cruel and unnatural in me, even in this confidence, to breathe it. But I cannot shake it off. Time and change (I have tried both before breaking silence) do nothing to wear it out. Remember, I was with my father. Remember, I saw his face when he gave the watch into my keeping, and struggled to express that he sent it as a token you would understand, to you. Remember, I saw him at the last with the pencil in his failing hand, trying to write some word for you to read, but to which he could give no shape. The more remote and cruel this vague suspicion that I have, the stronger the circumstances that could give it any semblance of probability to me. For Heaven's sake, let us examine sacredly whether there is any wrong entrusted to us to set right. No one can help towards it, mother, but you.'

Still so recoiling in her chair that her overpoised weight moved it, from time to time, a little on its wheels, and gave her the appearance of a phantom of fierce aspect gliding away from him, she interposed her left arm, bent at the elbow with the back of her hand towards her face, between herself and him, and looked at him in a fixed silence.

'In grasping at money and in driving hard bargains—I have begun, and I must speak of such things now, mother—some one may have been grievously deceived, injured, ruined. You were the moving power of all this machinery before my birth; your stronger spirit has been infused into all my father's dealings for more than two score years. You can set these doubts at rest, I think, if you will really help me to discover the truth. Will you, mother?'

He stopped in the hope that she would speak. But her grey hair was not more immovable in its two folds, than were her firm lips.

'If reparation can be made to any one, if restitution can be made to any one, let us know it and make it. Nay, mother, if within my means, let me make it. I have seen so little happiness come of money; it has brought within my knowledge so little peace to this house, or to any one belonging to it, that it is worth less to me than to another. It can buy me nothing that will not be a reproach and misery to me, if I am haunted by a suspicion that it darkened my father's last hours with remorse, and that it is not honestly and justly mine.'

Well, I'm sitting here reading this and thinking; "Good for you Arthur! I'm glad to know you haven't become what your mother has, at least you don't seem to be anything like her at this point." However, I'm also thinking that calling her the moving power in grasping at money and driving hard bargains, not to mention saying that she was the leading force behind someone possibly being grievously deceived, injured, ruined is not going to go over well with his mother even if true. And I'm right Mrs. Clennam rings the bell for her servant and orders the girl to get Flintwinch. She tells Flintwinch bitterly what has transpired, her version of it anyway. She then threatens to renounce Arthur if he ever mentions it again.

'In the days of old, Arthur, treated of in this commentary, there were pious men, beloved of the Lord, who would have cursed their sons for less than this: who would have sent them forth, and sent whole nations forth, if such had supported them, to be avoided of God and man, and perish, down to the baby at the breast. But I only tell you that if you ever renew that theme with me, I will renounce you; I will so dismiss you through that doorway, that you had better have been motherless from your cradle. I will never see or know you more. And if, after all, you were to come into this darkened room to look upon me lying dead, my body should bleed, if I could make it, when you came near me.'

Jeremiah tells Arthur he has no right to mistrust his father without "grounds to go upon" which makes me wonder if there are grounds to go upon. He then asks Mrs. Clennam if she knows what Arthur plans to do with the business and she tells him that he is planning to give it up and since Arthur says it is now hers to do with what she wants, she makes Jeremiah her partner. Jeremiah thanks her and then calls for her oysters, which I suppose she has every day at the same time, but this day she refuses to eat them, as Dickens tells us:

"But Mrs Clennam, resolved to treat herself with the greater rigour for having been supposed to be unacquainted with reparation, refused to eat her oysters when they were brought. They looked tempting; eight in number, circularly set out on a white plate on a tray covered with a white napkin, flanked by a slice of buttered French roll, and a little compact glass of cool wine and water; but she resisted all persuasions, and sent them down again—placing the act to her credit, no doubt, in her Eternal Day-Book."

That would be quite the thing to have in your Eternal Day-Book, I'm sure it got her quite a few bonus points with God. The oysters are served by the same girl who Arthur had seen there the previous night. She is described this way: