The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Book I Chapters 01 - 04

The second chapter, which is called “Fellow Travellers”, also begins in a sort of prison in that it features some travellers who are in quarantine since they came from “the East”, where the plague is still rife. Today is the day they are allowed to enter Marseilles. Among these travellers, the narrator singles out a handful of people who are going to play some role in the course of events. First of all, there are Mr. and Mrs. Meagles and their daughter, whom they call Pet. They also have some kind of maidservant travelling with them by the name of Harriet Beadle, but they call her Tattycoram. Then there is Arthur Clennam, whom we will follow into Chapters 3 and 4, and a young woman named Miss Wade. The narrator also mentions

The second chapter, which is called “Fellow Travellers”, also begins in a sort of prison in that it features some travellers who are in quarantine since they came from “the East”, where the plague is still rife. Today is the day they are allowed to enter Marseilles. Among these travellers, the narrator singles out a handful of people who are going to play some role in the course of events. First of all, there are Mr. and Mrs. Meagles and their daughter, whom they call Pet. They also have some kind of maidservant travelling with them by the name of Harriet Beadle, but they call her Tattycoram. Then there is Arthur Clennam, whom we will follow into Chapters 3 and 4, and a young woman named Miss Wade. The narrator also mentions ”a tall French gentleman with raven hair and beard, of a swart and terrible, not to say genteelly diabolical aspect, but who had shown himself the mildest of men”,

who does not play any important role in their conversation but who is mentioned all the same, and I have the strong suspicion that this may be the very cosmopolitan gentleman we have met in Chapter 1. On the other hand, this would mean that there must have been some lapse of time between the events recorded here and in Chapter 1 because how else could M. Rigaud made his way among the travellers. After all, they apparently came from the East, and we left him in the Marseilles prison at the end of the preceding chapter.

In giving us the background of the respective characters, Dickens proves once again the masterful narrator as whom we know him – for the information is not given by an omniscient narrator but seeps in, by and by, in the course of the conversation. We learn, for instance, that Mr. Meagles is not half as grumpy as he comes across at first sight and that he is anything but a practical man although he seems to be taking great pride in thinking himself to be one. He frankly tells Mr. Clennam that Pet used to have a twin sister, who died as a little child, and he comforts himself with the idea that on the day he passes on he will be greeted in the great by-and-by by a young woman the spitting image of his daughter Pet. Mr. Meagles also tells his new friend that they took Tattycoram into their house so that their daughter might have a playfellow and they took her from the Foundling Hospital in London. His kindheartedness becomes obvious when he says:

” ‘So I said next day: Now, Mother, I have a proposition to make that I think you'll approve of. Let us take one of those same little children to be a little maid to Pet. We are practical people. So if we should find her temper a little defective, or any of her ways a little wide of ours, we shall know what we have to take into account. We shall know what an immense deduction must be made from all the influences and experiences that have formed us—no parents, no child-brother or sister, no individuality of home, no Glass Slipper, or Fairy Godmother. And that's the way we came by Tattycoram.’

‘And the name itself—‘

‘By George!’ said Mr Meagles, ‘I was forgetting the name itself. Why, she was called in the Institution, Harriet Beadle—an arbitrary name, of course. Now, Harriet we changed into Hattey, and then into Tatty, because, as practical people, we thought even a playful name might be a new thing to her, and might have a softening and affectionate kind of effect, don't you see? As to Beadle, that I needn't say was wholly out of the question. If there is anything that is not to be tolerated on any terms, anything that is a type of Jack-in-office insolence and absurdity, anything that represents in coats, waistcoats, and big sticks our English holding on by nonsense after every one has found it out, it is a beadle. You haven't seen a beadle lately?’

‘As an Englishman who has been more than twenty years in China, no.’

‘Then,’ said Mr Meagles, laying his forefinger on his companion's breast with great animation, ‘don't you see a beadle, now, if you can help it. Whenever I see a beadle in full fig, coming down a street on a Sunday at the head of a charity school, I am obliged to turn and run away, or I should hit him. The name of Beadle being out of the question, and the originator of the Institution for these poor foundlings having been a blessed creature of the name of Coram, we gave that name to Pet's little maid. At one time she was Tatty, and at one time she was Coram, until we got into a way of mixing the two names together, and now she is always Tattycoram.’”

By the way, Dickens really seems to have had it in for beadles, don’t you think? Mr. Meagles also has the funny habit of addressing foreigners in idiomatic English, being somehow convinced that they would be able to understand him, and although he travels a lot for pleasure, he never picks up any vestige of the respective language that is spoken in the country. He also says something that might add to the topic of the novel:

”’One always begins to forgive a place as soon as it's left behind; I dare say a prisoner begins to relent towards his prison, after he is let out.’”

I somehow have the impression that Mr. Clennam himself has spent some of his lifetime in some sort of prison, and I wonder whether he is quite as forgiving about the circumstances of his confinement as Mr. Meagles supposes a prisoner to be. Of Mr. Clennam we learn that he was ”a grave man of forty” and he says about himself:

” […] I am such a waif and stray everywhere, that I am liable to be drifted where any current may set.’”

He rather despondently continues:

”’I have no will. That is to say,’—he coloured a little,—‘next to none that I can put in action now. Trained by main force; broken, not bent; heavily ironed with an object on which I was never consulted and which was never mine; shipped away to the other end of the world before I was of age, and exiled there until my father's death there, a year ago; always grinding in a mill I always hated; what is to be expected from me in middle life? Will, purpose, hope? All those lights were extinguished before I could sound the words. […]I am the son, Mr Meagles, of a hard father and mother. I am the only child of parents who weighed, measured, and priced everything; for whom what could not be weighed, measured, and priced, had no existence. Strict people as the phrase is, professors of a stern religion, their very religion was a gloomy sacrifice of tastes and sympathies that were never their own, offered up as a part of a bargain for the security of their possessions. Austere faces, inexorable discipline, penance in this world and terror in the next—nothing graceful or gentle anywhere, and the void in my cowed heart everywhere—this was my childhood, if I may so misuse the word as to apply it to such a beginning of life.’”

A poor lonesome stranger Mr. Clennam seems to be. And yet he seems to be more likeable than Miss Wade, who also is a lonesome woman, but who is proud and disdainful and rather prefers her own company over that of any of her fellow travellers. In connection with Mr. Meagles observation on prisons, Miss Wade states:

”’If I had been shut up in any place to pine and suffer, I should always hate that place and wish to burn it down, or raze it to the ground. I know no more.’”

She does not warm towards Pet the way everyone else does, but instead she ominously tells her:

”’In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads, […] what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done.’”

This sounds rather like a threat, or at least like an instance of extremely fatalistic thinking. Her words seem to acquire some hidden sort of meaning when later on, Miss Wade happens to run into Tattycoram, who is in a strange fit, inveighing against the Meagles and her daughter, accusing them with selfishness, but some moments later, Tattycoram repents her harsh words and retracts them, sobbing:

”’Go away from me, go away from me! When my temper comes upon me, I am mad. I know I might keep it off if I only tried hard enough, and sometimes I do try hard enough, and at other times I don't and won't. What have I said! I knew when I said it, it was all lies. They think I am being taken care of somewhere, and have all I want. They are nothing but good to me. I love them dearly; no people could ever be kinder to a thankless creature than they always are to me. Do, do go away, for I am afraid of you. I am afraid of myself when I feel my temper coming, and I am as much afraid of you. Go away from me, and let me pray and cry myself better!’”

I also had the impression that by reminding Tattycoram of her dependent position and entreating her to show patience, Miss Wade wanted to achieve the very opposite, but we will have to wait in order to see whether I was right or not – for here the chapter ends.

In Chapter 3, Arthur Clennam finally reaches his “Home”. I read somewhere that Dickens was very strongly opposed to (Puritan) Sabbatarianism as well as to all forms of extreme and cheerless Christianity. Just remember Mr. Snagsby who said that his little woman liked her religion rather sharp, and also remember the Chadbands or Mr. Pecksniff as dire examples of Christian humbugs and hypocrites. At the beginning of this chapter, the narrator describes every detail of a dismal, mirthless Sunday in order to voice Dickens’s criticism, and we see how Sunday used to be a kind of prison for Arthur Clennam in the days of his youth:

In Chapter 3, Arthur Clennam finally reaches his “Home”. I read somewhere that Dickens was very strongly opposed to (Puritan) Sabbatarianism as well as to all forms of extreme and cheerless Christianity. Just remember Mr. Snagsby who said that his little woman liked her religion rather sharp, and also remember the Chadbands or Mr. Pecksniff as dire examples of Christian humbugs and hypocrites. At the beginning of this chapter, the narrator describes every detail of a dismal, mirthless Sunday in order to voice Dickens’s criticism, and we see how Sunday used to be a kind of prison for Arthur Clennam in the days of his youth:”There was the dreary Sunday of his childhood, when he sat with his hands before him, scared out of his senses by a horrible tract which commenced business with the poor child by asking him in its title, why he was going to Perdition?—a piece of curiosity that he really, in a frock and drawers, was not in a condition to satisfy—and which, for the further attraction of his infant mind, had a parenthesis in every other line with some such hiccupping reference as 2 Ep. Thess. c. iii, v. 6 & 7. There was the sleepy Sunday of his boyhood, when, like a military deserter, he was marched to chapel by a picquet of teachers three times a day, morally handcuffed to another boy; and when he would willingly have bartered two meals of indigestible sermon for another ounce or two of inferior mutton at his scanty dinner in the flesh. There was the interminable Sunday of his nonage; when his mother, stern of face and unrelenting of heart, would sit all day behind a Bible—bound, like her own construction of it, in the hardest, barest, and straitest boards, with one dinted ornament on the cover like the drag of a chain, and a wrathful sprinkling of red upon the edges of the leaves—as if it, of all books! were a fortification against sweetness of temper, natural affection, and gentle intercourse. There was the resentful Sunday of a little later, when he sat down glowering and glooming through the tardy length of the day, with a sullen sense of injury in his heart, and no more real knowledge of the beneficent history of the New Testament than if he had been bred among idolaters. There was a legion of Sundays, all days of unserviceable bitterness and mortification, slowly passing before him.”

Mr. Clennam apparently does not feel a very strong intention to visit his home but eventually he does, and he finds it unchanged:

”It was a double house, with long, narrow, heavily-framed windows. Many years ago, it had had it in its mind to slide down sideways; it had been propped up, however, and was leaning on some half-dozen gigantic crutches: which gymnasium for the neighbouring cats, weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds, appeared in these latter days to be no very sure reliance.”

The door is opened to him by Mr. Flintwinch, the old family servant, whose outward appearance strangely seems to mirror the lopsidedness of the house:

”His neck was so twisted that the knotted ends of his white cravat usually dangled under one ear; his natural acerbity and energy, always contending with a second nature of habitual repression, gave his features a swollen and suffused look; and altogether, he had a weird appearance of having hanged himself at one time or other, and of having gone about ever since, halter and all, exactly as some timely hand had cut him down.”

There is not much love lost between Arthur and Mr. Flintwinch, and the servant grumpily leads Arthur before his mother, who is sitting in a wheelchair and who seems to take a grim pleasure in the fact that she – a prisoner, too – has not left her room the last 15 years, and that she has been conducting the family business from the confines of her room. Mrs. Clennam apparently considers herself morally superior to all those people who are able to leave their house and to interact with the world. She says that it has pleased God to put her into this position but there does not seem to be any humility in her behaviour and attitude. She also makes a point of not discussing business on a Sunday but nevertheless always starts discussing business herself. In her presence, Arthur feels like a child again and all those memories of his gloomy childhood, spent in the company of his father and his mother, who would never exchange a friendly word with each other, but just sat there like two marble statues, are rekindled. Mrs. Clennam takes her grimly frugal supper in Arthur’s company without ever asking her son whether he would like something to eat, too. This struck me as odd. But not only this. In the course of their dismal conversation, it becomes clear that Arthur’s father died somewhere abroad, probably in China, and that Arthur was with him during his last days. Mr. Clennam senior was very anxious that his watch be sent to his wife, and although Arthur could not detect anything unusual or noteworthy about or inside the watch, he took care that his father’s belongings were dispatched to Mrs. Clennam.

In the darkness of the room there are also two other people: There is a young girl, but she is never mentioned by the narrator at all. Only later, when Arthur and Mrs. Affery Flintwinch, who is the second bystander in the dark room, have a private conversation together, does Arthur ask about the girl, and he is given the answer that the young girl is Little Dorrit, whom Affery calls “a whim” of Mrs. Clennam’s. – I thought this rather an unusual way of introducing a character, let alone an eponymous character, but that’s Dickens.

Being asked why she is now married to Flintwinch, Affery confides to Arthur that she has actually been bullied into this union and that she stands no chance of her own against “the two clever ones”, as she calls Mr. Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam. Affery also tells Arthur that Flintwinch sometimes even quarrels with Mrs. Clennam and that he does not mince his words. At the same time she warns Arthur to stand up against them and not allow them to subdue him.

The fourth Chapter is rather short, and in it, “Mrs. Flintwinch Has a Dream”. In fact, the narrator gives us to understand that it might not really be a dream at all but something that Mrs. Flintwinch, after waking up from a few hours’ sleep, observes. Not finding her husband in bed next to her, Affery walks downstairs and sees, in a little room that is not normally used, two Mr. Flintwinches. One of them, her Jeremiah, is sitting at a table, watching the other Flintwinch, his double, sleeping. When the double finally awakes, there is a mysterious conversation going on between the two Flintwinches. The double is going to take a box with him, which is described like this:

The fourth Chapter is rather short, and in it, “Mrs. Flintwinch Has a Dream”. In fact, the narrator gives us to understand that it might not really be a dream at all but something that Mrs. Flintwinch, after waking up from a few hours’ sleep, observes. Not finding her husband in bed next to her, Affery walks downstairs and sees, in a little room that is not normally used, two Mr. Flintwinches. One of them, her Jeremiah, is sitting at a table, watching the other Flintwinch, his double, sleeping. When the double finally awakes, there is a mysterious conversation going on between the two Flintwinches. The double is going to take a box with him, which is described like this:”It was an iron box some two feet square, which he carried under his arms pretty easily. Jeremiah watched his manner of adjusting it, with jealous eyes; tried it with his hands, to be sure that he had a firm hold of it; bade him for his life be careful what he was about; and then stole out on tiptoe to open the door for him.”

Unfortunately, after the double has left, Jeremiah notices that his wife has been watching him, and once they are back in their bedchamber, he grabs her by the throat and shakes her, calling on to her to wake up as she had been dreaming again. He also tells her that if she has any more of those dreams, he will have to give her a large dose of her physic. Affery understands this thinly veiled threat and goes to bed again.

The description here -- of both setting and persons -- is quite powerful.

The description here -- of both setting and persons -- is quite powerful. That the one with the knife fears (and is subservient to) the one without a weapon says a lot about Rigaud. There's the jailer's daughter's reactions to her father's birds -- continuing with the caged birds theme in BH? -- not afraid of the one with a knife, but wary of the one without one.

And I feel a sense of entrapment when Rigaud's upper lip and nose trap his mustache. Rigaud's eyes are compared unfavorably to the King of Beasts. A lion's eyes are beady and close together, yet Rigaud's are less nobly set. When a lion fixes on prey its stare can rip right through you. Rigaud's stare plus his smile must be quite hypnotic.

Me thinks we have not seen the last of Rigaud.

Well now, isn't this a dark beginning?

Well now, isn't this a dark beginning? Prisons everywhere: Marseilles, plague and quarantine, the house, Clenham's personal prison, Tattycoram's, and Clenham's parents, prisoners who imprison their son.

A drenched and muddy London, church bells tolling, and though they toll for mass(?), I feel they toll for death.

That house. Oh, my gosh. That house is fighting a losing battle to gravity and time. I feel it feeds off the misery of its occupants. It's alive! A character in its own right. Marseilles's prison fares better by comparison, and it gets more light.

Mr. Meagles, who, though kind and cheery, is oblivious to what's in front of him, and, along with his wife, names his child Pet. Who names their child Pet. I wonder what the twin's name was? (And which one really survived :-) )

Who adopts -- if that's the right word -- a child to be a maid to another child? When Esther gets her maid, Charlie, in BH, Esther is grown, and the relationship between the two is clear. But here?

Did you notice how Tattycoram was not invited to the farewell dinner? Is Tattycoram daughter or maid? She is described as plaything and maid. Mr. Meagles is doing a good deed, yet he may be one of those people who goes through life thinking all is well oblivious to what's in front of him.

And Miss Wade, uncompromising, unyielding Miss Wade. What prison does she live in?

Yup, this is dark one.

Oh good! I'm happy to learn the group is reading _Little Dorrit_. I'll try to follow along. -Like it very much.

Oh good! I'm happy to learn the group is reading _Little Dorrit_. I'll try to follow along. -Like it very much.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,finally we are meeting again over one of Dickens’s chunky novels, one of those you could take with you on a week’s journey without fearing to run out of Dickens, and it is my pl..."

Ah yes, Tristram. a wonderfully thick, heavy book to get us through the summer months. Let's hope the weather this year is more moderate than in chapter one.

I liked your comparison of Rigaud as a devilish character and the counterbalancing character of John Baptist. Dickens does tend to give his readers these opposites, doesn't he? In this way, each character tends to sharpen the details and character of the other.

I also enjoyed the soaring prose of Dickens again. Long descriptive passages that seem to expand forever rather than those in HT which seemed to be a collection of precis at times.

The description of the prison was lush. If the opening of BH prepared us for the world of London, then this opening chapter has set the stage for the world of imprisonment.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning? Prisons everywhere:

You are so right. I liked your comments about the house. Not exactly one I'd attempt to renovate. One of my quirks in reading is watching how a novelist describes the homes of the characters and then observing how the residents of that structure further enhance or contradict the place they live. So far we have had the jail and its two featured characters and now we have the Clennam home. As you said, prisons within prisons.

nb. I have no idea why my comments are in italics and also have no idea how to change it. Sorry!

Tristram wrote: "In Chapter 3, Arthur Clennam finally reaches his “Home”. I read somewhere that Dickens was very strongly opposed to (Puritan) Sabbatarianism as well as to all forms of extreme and cheerless Christi..."

Tristram wrote: "In Chapter 3, Arthur Clennam finally reaches his “Home”. I read somewhere that Dickens was very strongly opposed to (Puritan) Sabbatarianism as well as to all forms of extreme and cheerless Christi..."In these opening chapters Dickens rolls out some remarkable characters. Some, like Rigaud have evil pasts. Some, like Tattycoram, nicknamed Tatty, whose real name is evidently Harriet Beadle, has an unknown past. Some, like Pet, have a clearly defined past but, like Tattycoram, a new name. Pet has a twin, but the twin is evidently dead, and rounding it all out we have Miss Wade who makes the ominous comment that in life we shall meet people who are coming to meet us. Past and present; changed names; new identities. Ah, Dickens.

The title page

The title page

Commentary:

"Hablot Browne (Phiz) provided all 40 illustrations for Little Dorrit published in monthly parts Dec 1855 - June 1857.

Browne continues to use the dark plate technique, as in Bleak House. He also continues to reduce the use of emblematic detail in the illustrations."

Interesting note. In the preface to the 1857 edition of Little Dorrit, Dickens writes -

Interesting note. In the preface to the 1857 edition of Little Dorrit, Dickens writes -In the Preface to Bleak House I remarked that I had never had so many readers. In the Preface to its next successor, Little Dorrit, I have still to repeat the same words.

I was a little suprised that he described Little Dorrit as the next successor to Bleak House.

Kim

KimIt's good to see the illustrations again. While you did provide some wonderful examples of illustrations for HT they were not Phiz.

The dark print of "The Birds in the Cage" is quite remarkable. The title page with Little Dorrit going through the jail door is certainly a classic. Phiz captures the mood perfectly.

Thanks Kim

I can't help myself! Even though I'm not currently reading Little Dorrit with you, it's one of my favorites, and I find myself lurking here among the commentary.

I can't help myself! Even though I'm not currently reading Little Dorrit with you, it's one of my favorites, and I find myself lurking here among the commentary. Now that I have a few Dickens' books with the group under my belt, I'm finding it very interesting to compare and contrast, and see recurring themes in the books. Case in point, the metaphor of the caged birds. Will they continue to pop up in LD as they did in BH?

Without giving anything away, I'm fascinated to realize just from Tristram's summaries how much foreshadowing is done here in these first few chapters, and how masterful Dickens is at setting the stage for what is to come. Great novels need to be read twice, if only to go back and realize how amazing the opening chapters were in the context of the book as a whole.

Peter -- I love what you said about looking at the description of homes. As I was dusting my family room several years ago, I was shocked to realize that I'd quite inadvertently filled my home with homes - a watercolor of a cottage; a large print of a row of townhouses; a small model of a Japanese house, one of a house in Bermuda, and another of an English cottage; a smaller watercolor of a castle in Germany, etc. I hadn't set out to collect these things, and most of them weren't even purchases I'd made, but obviously I was drawn to them and, like you, I pay attention to fictional homes as well. Is there a psychologist in the group who'd like to analyze this inclination? :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "I can't help myself! Even though I'm not currently reading Little Dorrit with you, it's one of my favorites, and I find myself lurking here among the commentary.

Mary Lou wrote: "I can't help myself! Even though I'm not currently reading Little Dorrit with you, it's one of my favorites, and I find myself lurking here among the commentary. Now that I have a few Dickens' bo..."

Mary Lou

I have no exact idea where my quirk (obsession?) with taking a long look at houses described by an author comes from but I suspect my early Dickens reading has something to do with it.

As you are probably aware from our earlier readings I also seek out references to birds, bird cages and the like as well. Naturally, I was in heaven during our reading of Bleak House and all the additional illustrations from the various artists that Kim gave us as well. If I were ever to rest on a psychiatrist's couch I'd have to confess to having a bird and house, or would that be a bird house fetish. Oh my ...

I hope you do join us off and on during our read of LD. To conclude my couch confession, feel free to chirp in anytime. :-))

I just started this last night, but did not get very far before falling asleep after a long weekend of gardening and soccer. But my thoughts while reading the first couple of pages describing the hot staring blistering sun was what a stark contrast it was to Bleak House's fog, fog, mud, mud, and more fog and mud. I love Dickens' use of repeating the descriptions over and over again so it becomes completely ingrained into the reader. I have just begun reading the prison setting, so I know we have moved from the hot blaring sun outside to the cold dark damp prison setting inside, which makes the prison setting that much more gloomy after having been in the hot sun.

I just started this last night, but did not get very far before falling asleep after a long weekend of gardening and soccer. But my thoughts while reading the first couple of pages describing the hot staring blistering sun was what a stark contrast it was to Bleak House's fog, fog, mud, mud, and more fog and mud. I love Dickens' use of repeating the descriptions over and over again so it becomes completely ingrained into the reader. I have just begun reading the prison setting, so I know we have moved from the hot blaring sun outside to the cold dark damp prison setting inside, which makes the prison setting that much more gloomy after having been in the hot sun.

Mary Lou wrote: "Case in point, the metaphor of the caged birds. Will they continue to pop up in LD as they did in BH? "

Mary Lou wrote: "Case in point, the metaphor of the caged birds. Will they continue to pop up in LD as they did in BH? "I was wondering that myself, Mary Lou. First thing I thought of was Miss Flite's birds.

Peter wrote: "While you did provide some wonderful examples of illustrations for HT they were not Phiz."

Peter wrote: "While you did provide some wonderful examples of illustrations for HT they were not Phiz."And now that you mentioned other illustrations, here is one by Sol Eytinge:

Little Dorrit and her Father

Sol Eytinge

Frontispiece for Dickens's Little Dorrit in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston) Diamond Edition (1867).

Commentary:

"Little Dorrit and Her Father," is the first full-page illustration, facing the title-page of the Diamond edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1871), frontispiece.

The first illustration — "Little Dorrit and Her Father" — introduces the novel's focal characters. The dual character study is different from others in Eytinge's Diamond Edition sequences of sixteen for each volume in that it post-dates Eytinge's 1869 visit to London and Gadshill. As is typical of these studies, Eytinge appears to have in mind no particular moment in the narrative.

Amy, William's youngest child, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger."

Kim wrote: "Commentary:

Kim wrote: "Commentary:... the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger."

An understatement! Either Mr. Dorrit is a giant, or little Amy is five! I like the rendition of her father, but can't say that Eytinge's Amy is anything remotely like the picture in my head. She looks very sad here, as well as diminutive.

Amy, William's youngest child, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, ,even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger."

Amy, William's youngest child, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, ,even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger." That's the point.

The cover drawing of Amy is very good.

And another by Eytinge:

And another by Eytinge:

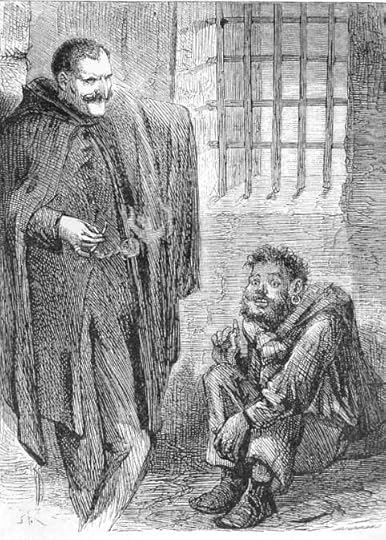

Rigaud and Cavalletto

Illustration for Little Dorrit in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston), 1871, Diamond Edition.

Commentary:

"Rigaud and Cavalletto," the second full-page illustration, facing page 6 of the Diamond Edition, by Sol Eytinge, Jr., in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1871).

The second illustration like the first — "Little Dorrit and Her Father" — introduces the characters in a characteristic setting: whereas the first pair were in Dorrit's rooms in the Marshalsea, here the characters are clearly situated in a prison cell (in fact, as we learn from the text, the Marseilles Prison), as emphasized by the lattice-work of iron bars in the window and the thickness of the stone wall. The dual character presentation is a study in binary opposites; it depends for its effectiveness on the extreme contrast between the cell-mates, for Monsieur Rigaud (standing, left) is suave, composed, well-dressed, and dominant, while Cavelletto (seated, right) seems almost simian, a Darwinian throwback with thick hair, in contrast to Rigaud's much trimmer hair style, and peasant clothing in contrast to the other's gentlemanly, cosmopolitan attire. As a somewhat hairsuit individual in Eytinge's wood-cut Cavalletto is worthy of his Christian names , "John Baptiste" (as Dickens notes in Pictures from Italy, the most common masculine name in Genoa, where the writer spent much of 1844). Eytinge distinguishes the two in terms of the text, for whereas tall Rigaud is "sinister" Cavalletto is specifically a "little man" squatting on the pavement "contentedly," a merry, good-hearted, earthy sort of fellow. However, whereas only the diabolic Rigaud is apparently smoking in the 1871 illustration, in the text both have lit cigarettes. Since Rigaud is standing and their midday meal finished, the passage illustrated is likely this:

"I am a," — Monsieur Rigaud stood up to say it, — "I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss, — Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world."

His theatrical air, as he stood with one arm on his hip, within the folds of his cloak, together with his manner of disregarding his companion and addressing the opposite wall instead, seemed to intimate that he was rehearsing for the President [of the Justice Tribunal, about to pass judgment on Rigaud for the murder of his wife], whose examination he was shortly to undergo, rather than troubling himself merely to enlighten so small a person as John Baptist Cavalletto. [Chapter One, "Sun and Shadow,"]

Here is an illustration by Felix O. C. Darley:

Here is an illustration by Felix O. C. Darley:

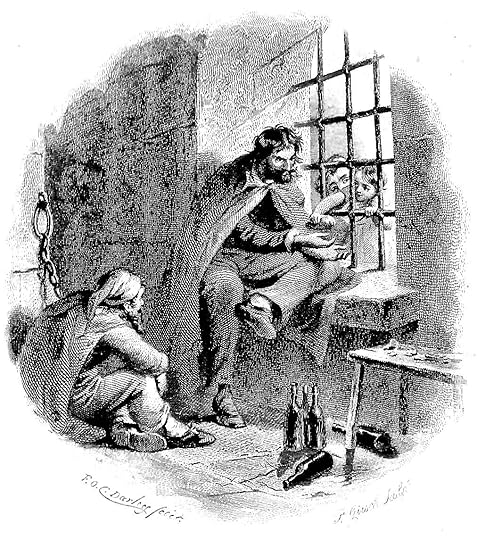

Feeding the Birds

F. O. C. Darley

Frontispiece for Dickens's Little Dorrit, volume 1, in the Sheldon & Co. (NewYork) Household Edition (1863).

Passage Illustrated

"The other man spat suddenly on the pavement, and gurgled in his throat.

Some lock below gurgled in its throat immediately afterwards, and then a door crashed. Slow steps began ascending the stairs; the prattle of a sweet little voice mingled with the noise they made; and the prison-keeper appeared carrying his daughter, three or four years old, and a basket.

"How goes the world this forenoon, gentlemen? My little one, you see, going round with me to have a peep at her father's birds. Fie, then! Look at the birds, my pretty, look at the birds."

He looked sharply at the birds himself, as he held the child up at the grate, especially at the little bird, whose activity he seemed to mistrust. "I have brought your bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian); "and if I might recommend you not to game —"

"You don't recommend the master!" said John Baptist, showing his teeth as he smiled.

"Oh! but the master wins," returned the jailer, with a passing look of no particular liking at the other man, "and you lose. It's quite another thing. You get husky bread and sour drink by it; and he gets sausage of Lyons, veal in savoury jelly, white bread, strachino cheese, and good wine by it. Look at the birds, my pretty!"

"Poor birds!" said the child.

The fair little face, touched with divine compassion, as it peeped shrinkingly through the grate, was like an angel's in the prison. John Baptist rose and moved towards it, as if it had a good attraction for him. The other bird remained as before, except for an impatient glance at the basket.

"Stay!" said the jailer, putting his little daughter on the outer ledge of the grate, "she shall feed the birds. This big loaf is for Signor John Baptist. We must break it to get it through into the cage. So, there's a tame bird to kiss the little hand! This sausage in a vine leaf is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — this veal in savoury jelly is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — these three white little loaves are for Monsieur Rigaud. Again, this cheese — again, this wine — again, this tobacco — all for Monsieur Rigaud. Lucky bird!"

Commentary:

"The scene is a prison cell in Marseilles about 1820 in the month of August, and the characters depicted in the Darley frontispiece are Monsieut Rigaud, a wealthy Frenchman accused of murdering his wife, and John Baptist Cavalletto, a Genoese smuggler, for whom the turnkey and his daughter have radically different meals as Rigaud can afford to supplement the Spartan prison diet with a number of luxuries. The illustration makes it clear that the novel begins inside a prison cell. Not evident in the cavernous darkness of Phiz's The Birds in the Cage (Book One, Chapter 1), the jailor and his young daughter, faces at the bars, are subordinated in Darley's frontispiece to the villainous Rigaud. Darley's Rigaud is a realistic version of the bearded, satanic foreigner, an "other" to the novel's smooth-faced Englishmen."

Someone else liked these two prisoners and the birds, here is an illustration by Harry Furniss:

Someone else liked these two prisoners and the birds, here is an illustration by Harry Furniss:

Feeding the Birds; Rigaud and John Baptist Imprisoned at Marseilles

Harry Furniss

Illustration for Dickens's Little Dorrit, Vol. 12 of Charles Dickens Library Edition, Book the First, "Poverty"; Chapter 1, "Sun and Shadow," 1910

Passage Illustrated

"How goes the world this forenoon, gentlemen? My little one, you see, going round with me to have a peep at her father's birds. Fie, then! Look at the birds, my pretty, look at the birds."

He looked sharply at the birds himself, as he held the child up at the grate, especially at the little bird, whose activity he seemed to mistrust. "I have brought your bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian); "and if I might recommend you not to game —"

"You don't recommend the master!" said John Baptist, showing his teeth as he smiled.

"Oh! but the master wins," returned the jailer, with a passing look of no particular liking at the other man, "and you lose. It's quite another thing. You get husky bread and sour drink by it; and he gets sausage of Lyons, veal in savoury jelly, white bread, strachino cheese, and good wine by it. Look at the birds, my pretty!"

"Poor birds!" said the child.

The fair little face, touched with divine compassion, as it peeped shrinkingly through the grate, was like an angel's in the prison. John Baptist rose and moved towards it, as if it had a good attraction for him. The other bird remained as before, except for an impatient glance at the basket.

"Stay!" said the jailer, putting his little daughter on the outer ledge of the grate, "she shall feed the birds. This big loaf is for Signor John Baptist. We must break it to get it through into the cage. So, there's a tame bird to kiss the little hand! This sausage in a vine leaf is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — this veal in savoury jelly is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — these three white little loaves are for Monsieur Rigaud. Again, this cheese — again, this wine — again, this tobacco — all for Monsieur Rigaud. Lucky bird!"

The child put all these things between the bars into the soft, smooth, well-shaped hand, with evident dread — more than once drawing back her own and looking at the man with her fair brow roughened into an expression half of fright and half of anger. Whereas she had put the lump of coarse bread into the swart, scaled, knotted hands of John Baptist (who had scarcely as much nail on his eight fingers and two thumbs as would have made out one for Monsieur Rigaud), with ready confidence; and, when he kissed her hand, had herself passed it caressingly over his face. Monsieur Rigaud, indifferent to this distinction, propitiated the father by laughing and nodding at the daughter as often as she gave him anything; and, so soon as he had all his viands about him in convenient nooks of the ledge on which he rested, began to eat with an appetite."

Commentary

"Furniss's re-interpretation of the opening scene in Marseilles is the reverse of Phiz's The Birds in the Cage (Book One, Chapter 1), in that, whereas the faces of the jailor and his young daughter are barely discernible in the original, they are the central figures in this 1910 pen-and-ink drawing, and the prisoners are mere faces at the bars. Rather than emphasize the darkness and darkness of the cell, Furniss shows two sets of bars and a very substantial stone staircase to imply the stoutness of the walls. He subordinates his ill-kempt prisoners to the figure of the jailor and his daughter, in complete contrast to their being the focal point in Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece entitled Feeding the Birds. Whereas Darley emphasizes the villainous Rigaud, a satanically-bearded, gentlemanly accused murderer, Harry Furniss has the reader experience the scene from the perspective of the uniformed jailor.

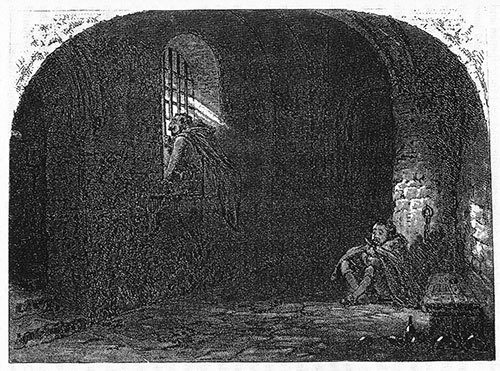

This is the last one, I think, of the prisoners, it is by James Mahoney:

This is the last one, I think, of the prisoners, it is by James Mahoney:

Rigaud and Cavaletto

James Mahoney

"In Marseilles that day there was a villainous prison. In one of its chambers, so repulsive a place, that even the obtrusive stare blinked at it, and left it to such refuse of reflected light as it could find for itself, were two men."

Book I, chap. 1,

James Mahoney's illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1875

Commentary (these commentaries are all starting to sound alike to me):

"The scene, as in the original Hablot Knight Browne December 1855 illustration The Birds in the Cage, is a dank, poorly-lit prison cell in Marseilles about 1820 in the month of August, and the characters depicted in the Mahoney wood-engraving are Monsieur Rigaud, a wealthy Frenchman accused of murdering his wife, and John Baptist Cavalletto, a Genoese smuggler, for whom the turnkey and his daughter have radically different meals as Rigaud can afford to supplement the spartan prison diet with a number of luxuries.

There is more than a whiff of Brimstone about Rigaud in the Mahoney illustrations as he is depicted smoking in his initial appearance, bearded, self-confidant, perpetually smiling. A pool of light, presumably emanating from the cell's small window, contains Mahoney's initial and enables the artist to show a niche in the back wall, the straw on the floor, and Rigaud's resigned cellmate, the affable Genoese smuggler Giovanni Battista.

Although Mahoney shows neither the window nor the turnkey and his daughter, this illustration seems to be directly derived from Phiz's original dark plate The Birds in the Cage — Book One, Chapter One (December 1855)."

Kim

KimWow. What great illustrations by a variety of artists. Is this a first for F. O. C. Darley?

I have a whole new list of illustrations to note in my "bird" collection.

Thanks, as always, Kim.

Here's what I know about Darley and Dickens:

Here's what I know about Darley and Dickens:"Some ten years younger than the British author whose works he illustrated in the fifty-five volume so-called "Household Edition" for New York publisher James G. Gregory, Philadelphia-born artist Felix Octavius Carr Darley was recognized in his era as one of the chief illustrators of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Washington Irving, and Edgar Allen Poe, although he also illustrated such lesser American writers as Mary Maples Dodge, George Lippard, Donald Grant Mitchell, Clement Clarke Moore, Frances Parkman, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The son of an English actor, Darley, a skilled draughtsman, did large-scale genre prints such as "The Wedding Procession" and "The Village Blacksmith," as well as historical subjects such as "Washington's Entry into New York" (from Washington Irving's 1860 five-volume The Life of George Washington, G. P. Putnam, 1862). After moving to New York City in 1848, he became a house artist for Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization from its founding, supplying wood-engravings for the periodical, but lithographs and photogravure prints for such series as the complete works of James Fenimore Cooper (1859-1861), for which, prior to undertaking Dickens, Darley had executed more than five hundred illustrations. His "Household Edition" Dickens illustrations were subsequently reproduced in Houghton Mifflin's Standard Library Edition in 32 volumes (Boston, 1894). Darley also provided six plates for Children from Dickens's Novels and eight photogravures for the Imperial Edition of Dickens's works, issued in considerable numbers by Estes and Lauriat, Boston. Leaving New York in 1859 with his bride, he took up residence at Darley House in Clayton, Delaware, where Charles Dickens visited him while on his second reading tour of the United States in 1867. Although he died in Clayton on 27 March 1888, Felix Octavius Carr Darley is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His best-known picture, often reproduced, remains "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" for the 1862 Christmas book of the same name by Clement Clarke Moore."

I can't resist:

Tristram wrote: "And by my trouthe! don’t we get a lot of sun at the beginning, "

Tristram wrote: "And by my trouthe! don’t we get a lot of sun at the beginning, "Not only a Dickens scholar, but a Chaucerian!

The opening on the sun reminded me of nothing so powerfully as the description of fog in Bleak House. Both extraordinary descriptions of the natural phenomena. Fog was certainly a metaphor for much that took place in Bleak House. Will sun be a metaphor for events and characters in Little Dorrit? A question perhaps to keep in mind as we read into the book.

Kim wrote: "Here's what I know about Darley and Dickens:

Kim wrote: "Here's what I know about Darley and Dickens:"Some ten years younger than the British author whose works he illustrated in the fifty-five volume so-called "Household Edition" for New York publishe..."

Kim

How appropriate that after all your work finding these illustrations for us that F. O. C. Darley would turn out to be not only the illustrator of "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" by the famous Clement Clarke Moore but a person who had a visit from Charles Dickens in 1867.

I love all the neat Dickens interconnections that occur.

Mary Lou wrote: "Great novels need to be read twice.."

Mary Lou wrote: "Great novels need to be read twice.."At least.

Not only great novels, but most great books. It's hard for me to think of a great book that doesn't deserve re-reading over and over.

Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning?

Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning? Prisons everywhere:

You are so right. I liked your comments about the house. Not exactly one I'd attempt to renovate. One of my..."

Peter, your comment might be all in italics because your quotation of Xan might not have the correct html sign at the end but just something similar?

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "And by my trouthe! don’t we get a lot of sun at the beginning, "

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "And by my trouthe! don’t we get a lot of sun at the beginning, "Not only a Dickens scholar, but a Chaucerian!

The opening on the sun reminded me of nothing so powerfully as the..."

And, as I like having a good cup of coffee while I am reading these comments, doubtless a saucerian, too.

Everyman wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Great novels need to be read twice.."

Everyman wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Great novels need to be read twice.."At least.

Not only great novels, but most great books. It's hard for me to think of a great book that doesn't deserve re-reading over and over."

Not only do classic books deserve to be read over and over again, but I also tend to read them aloud - whenever I am alone, at least - because then, as with Dickens's opening chapters of fog and sun, the effect that is intended becomes even stronger. I tell my students that they should read aloud at home because this makes literature come even more alive, and something that cannot bear being read aloud is simply no good literature.

My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them.

Mark wrote: "Oh good! I'm happy to learn the group is reading _Little Dorrit_. I'll try to follow along. -Like it very much."

Mark wrote: "Oh good! I'm happy to learn the group is reading _Little Dorrit_. I'll try to follow along. -Like it very much."Indeed, Mark, it is strange that Dickens seems to have forgotten about Hard Times. Maybe he was not so satisfied with this book after all?

About the illustration of Little Dorrit and her father by Eytinge:

About the illustration of Little Dorrit and her father by Eytinge:At first, I thought the two people in the picture were Mr. Meagles and his daughter Pet, all the more so after reading Xan's insightful remarks on Mr. Meagles's lack of foresight. The male figure in the picture appears to me quite self-complacent and at ease with himself, and this is also what I would assume of Mr. Meagles, who does not even bother to pick up little phrases of the languages that are spoken in the countries he visits. The position of the female figure - she does look quite sad but also very submissive - to my mind also goes perfectly with someone who is constantly called Pet by her parents.

Clearly, we are meant to like Mr. Meagles - otherwise the narrator would not have given us the sad background story of the twin who has died -, but as happens so often with me, I am not overly fond of the characters Dickens wants us to like. The Meagles' treatment of Tattycoram is definitely, to use a neutral term, noteworthy. We will see what it is going to lead to.

Kim wrote: ""Under the Microscope"

Kim wrote: ""Under the Microscope"Chapter 2

Phiz"

"Under the microscope" is a very meaningful title for the illustration. We don't know anything about Miss Wade yet other than that she is carrying her own prison along with her - but she seems to be able to read Tatty like an open book.

Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them. "

Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them. "This gave me the smile I needed to start my day off right. :-)

Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them."

Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them."I could only hope for such a neighbor as yourself, Tristram! :)

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning?

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well now, isn't this a dark beginning? Prisons everywhere:

You are so right. I liked your comments about the house. Not exactly one I'd attempt to renov..."

Thanks Tristram. I really didn't understand what you said but that's me, not you. Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots?

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them. "

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them. "This gave me the smile ..."

Anything to oblige a lady :-)

Linda wrote: "Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them."

Linda wrote: "Tristram wrote: "My neighbours sometimes wonder when I am sitting on the balcony reading Dickens or Conrad aloud but I consider this as a kind of boon lavished upon them."I could only hope for su..."

It's raining compliments today, so I'll leave my umbrella at home.

Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots?"

Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots?"A good question. Writing has become way too easy without quill pens and ink pots, and so people have started writing a lot of useless stuff - called "the bulk of 20th century literature" ;-)

Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "

Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "Have you ever tried writing with a quill pen?

I went through a phase when I tried writing with a steel nib pen (a step up from quill, but still dipped into the inkwell ever few letters). It was frustrating, but many calligraphers and artists still use these dip pens, though it must take some experience to be easy with them. The steel nib replaced the quill pen I think sometime after 1800.

Attempts to avoid the constant dipping were made starting at least a thousand years ago, but the first really useful fountain pen that held an internal reservoir of ink was, I believe, in the early to mid 1800s.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "Have you ever tried writing with a quill pen?

I went through a phase when I tried writing with a steel nib pen (a st..."

I tried a fountain pen back in university, why I don't know. Remember the cartridges of ink you put inside the barrel? Oh my. What a mess! So much for my fountain pen days.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why and when did the world stop using quill pens and ink pots? "Have you ever tried writing with a quill pen?

I went through a phase when I tried writing with a steel nib pen (a st..."

And may eternal celestial bliss be showered upon the inventor of the fountain pen and may choirs of angels sing him graceful lullabies - although lullabies sung by choirs tend to have the opposite effect! Because I love writing with a good fountain pen. I tried a quill once but could not muster up enough patience and dexterity.

But history repeats itself, and Hegel was right in a way, though unreadable in all ways: Writing a message on a modern smartphone that even has auto-correct features and keeps replacing words is at least as cumbersome as writing with a quill.

finally we are meeting again over one of Dickens’s chunky novels, one of those you could take with you on a week’s journey without fearing to run out of Dickens, and it is my pleasure to recap the first chapters of the novel. By the way, I might also recap Dickens’s preface to the 1857 edition sometime later.

Now let’s not waste any more time on preliminaries and circumlocution and start right away with Book the First “Poverty”, Chapter 1, which is entitled “Sun and Shadow”. And by my trouthe! don’t we get a lot of sun at the beginning, which is set in Marseilles, “thirty years ago”, which would fix the date around 1825 or ’26. Dickens brilliantly conjures up the unpleasant atmosphere of a Southern European summer, when the sun glares like a lidless, inhuman eye at every single thing beneath:

”Everything in Marseilles, and about Marseilles, had stared at the fervid sky, and been stared at in return, until a staring habit had become universal there. Strangers were stared out of countenance by staring white houses, staring white walls, staring white streets, staring tracts of arid road, staring hills from which verdure was burnt away. The only things to be seen not fixedly staring and glaring were the vines drooping under their load of grapes. These did occasionally wink a little, as the hot air barely moved their faint leaves. […]The universal stare made the eyes ache. Towards the distant line of Italian coast, indeed, it was a little relieved by light clouds of mist, slowly rising from the evaporation of the sea, but it softened nowhere else. Far away the staring roads, deep in dust, stared from the hill-side, stared from the hollow, stared from the interminable plain. Far away the dusty vines overhanging wayside cottages, and the monotonous wayside avenues of parched trees without shade, drooped beneath the stare of earth and sky. So did the horses with drowsy bells, in long files of carts, creeping slowly towards the interior; so did their recumbent drivers, when they were awake, which rarely happened; so did the exhausted labourers in the fields. Everything that lived or grew, was oppressed by the glare; except the lizard, passing swiftly over rough stone walls, and the cicala, chirping his dry hot chirp, like a rattle. The very dust was scorched brown, and something quivered in the atmosphere as if the air itself were panting.

Blinds, shutters, curtains, awnings, were all closed and drawn to keep out the stare. Grant it but a chink or keyhole, and it shot in like a white-hot arrow. The churches were the freest from it. To come out of the twilight of pillars and arches—dreamily dotted with winking lamps, dreamily peopled with ugly old shadows piously dozing, spitting, and begging—was to plunge into a fiery river, and swim for life to the nearest strip of shade. So, with people lounging and lying wherever shade was, with but little hum of tongues or barking of dogs, with occasional jangling of discordant church bells and rattling of vicious drums, Marseilles, a fact to be strongly smelt and tasted, lay broiling in the sun one day.”

It is surely a day one would prefer to spend indoors, but the kind of indoors offered to us by the narrator is not much better than a sojourn outside on that relentlessly sunny day. The narrator takes us inside ”a villainous prison”, thus introducing one motif that is going to become very important in this novel, most of you probably knowing that the Marshalsea, the infamous debtor’s prison is going to play a major role. It was here that Dickens’s father was put in 1824, i.e. around the time the novel begins, for owing some money to a baker. Dickens himself was 12 at that time and seeing his father incarcerated within the grim prison walls must have made a deep impression on the child’s mind. The narrator leaves no doubt as to the corrupting influence of the prison atmosphere when he writes:

”A prison taint was on everything there. The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men, were all deteriorated by confinement. As the captive men were faded and haggard, so the iron was rusty, the stone was slimy, the wood was rotten, the air was faint, the light was dim. Like a well, like a vault, like a tomb, the prison had no knowledge of the brightness outside, and would have kept its polluted atmosphere intact in one of the spice islands of the Indian ocean.>”

There are two prisoners in the cell we are introduced to: One of them has an outward appearance that is not very prepossessing:

”[H]is eyes, too close together, were not so nobly set in his head as those of the king of beasts are in his, and they were sharp rather than bright—pointed weapons with little surface to betray them. They had no depth or change; they glittered, and they opened and shut. So far, and waiving their use to himself, a clockmaker could have made a better pair. He had a hook nose, handsome after its kind, but too high between the eyes by probably just as much as his eyes were too near to one another. For the rest, he was large and tall in frame, had thin lips, where his thick moustache showed them at all, and a quantity of dry hair, of no definable colour, in its shaggy state, but shot with red. The hand with which he held the grating (seamed all over the back with ugly scratches newly healed), was unusually small and plump; would have been unusually white but for the prison grime.”

This man is called Monsieur Rigaud. Later on we learn that whenever he laughs, his moustache would go upwards and his nose would move down, which gives him a very sinister and cruel air.

”'I am a'—Monsieur Rigaud stood up to say it—'I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss—Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world.'“

I could not help thinking that the label of being a cosmopolitan gentleman, owning no particular country, seems to imply that Rigaud is the Devil himself, because the Old Gentleman is also a man of the world, a globetrotter, who is at home everywhere. In a way, I also felt reminded of Mlle Hortense, who was also born in Belgium, unless I am mistaken, and so I fully expect M. Rigaud to play an important, if sinister, role in the course of the events that will be told in the novel.

The other prisoner is an Italian by the name of John Baptist – where there is a devil, there must be a John Baptist – Cavalletto, who has been taken to prison for smuggling. Signore Cavalletto is described like this:

”A sunburnt, quick, lithe, little man, though rather thickset. Earrings in his brown ears, white teeth lighting up his grotesque brown face, intensely black hair clustering about his brown throat, a ragged red shirt open at his brown breast. Loose, seaman-like trousers, decent shoes, a long red cap, a red sash round his waist, and a knife in it.”

I was, and still am, puzzled at the little detail of the prisoner being allowed to keep a knife, obviously some sort of dagger, in the prison cell, but maybe in those days prisoners were allowed to keep weapons on them.

When the prison warden comes in order to give the prisoners their food – they obviously have to pay for their own food, which accounts for the fact that Rigaud feasts much more sumptuously than Cavallatto –, he has his little daughter with him, who wants to feed her ”father’s birds”. M. Rigaud is told that after the meal he is going to be taken before the judges, and this prospect apparently puts him down and spoils his appetite a little bit. Nevertheless he takes the opportunity to state his case before Cavalletto, obviously with a view to practising to defend himself before the judge. We learn that he took lodgings with a well-to-do landlord, who mysteriously died within half a year. M. Rigaud then married the man’s young widow, on whom the property was settled, but they used to quarrel a lot. One day when they were walking along a cliff, Mme Rigaud, in a fit of temper, attacked M. Rigaud, and in the course of their quarrel, she fell off the cliff, by accident.

We are left to our own devices as to whether we should believe M. Rigaud’s story or not. The people of Marseille, however, seem to entertain serious doubts because quite a bunch of them are protesting in front of the prison, eagerly demanding that M. Rigaud be meted out his just punishment. Cavalletto, of whom we get a much more favourable impression, seems to listen attentively to M. Rigaud’s account of the crime he is charged with, from time to time being thrown a cigarette by his fellow-prisoner. By the way, the annotations in my Penguin edition told me that at that time cigarettes were still so rare that they were considered to be a delicacy. Finally, Rigaud is led out of the cell, and Cavalletto is left alone again. We may be quite sure that the cosmopolitan gentleman will be able to wriggle the judge around his finger.