The Pickwick Club discussion

Hard Times

>

Part I Chapters 07-08

Our next chapter, Chapter 8 is titled "Never Wonder" and if these people can go through life never "wondering" about anything at all then I do feel sorry for them, even Bounderby, a little, little bit. We start with Gradgrind telling Louisa to never wonder and Mr. Choakumchild telling us to bring him a baby and he will guarantee it will never wonder. Gradgrind is also worried about the types of books working people are reading in the library.

Our next chapter, Chapter 8 is titled "Never Wonder" and if these people can go through life never "wondering" about anything at all then I do feel sorry for them, even Bounderby, a little, little bit. We start with Gradgrind telling Louisa to never wonder and Mr. Choakumchild telling us to bring him a baby and he will guarantee it will never wonder. Gradgrind is also worried about the types of books working people are reading in the library. "It was a disheartening circumstance, but a melancholy fact, that even these readers persisted in wondering. They wondered about human nature, human passions, human hopes and fears, the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the cares and joys and sorrows, the lives and deaths of common men and women! They sometimes, after fifteen hours’ work, sat down to read mere fables about men and women, more or less like themselves, and about children, more or less like their own. "

Thankfully neither Gradgrind or Bounderby seem to have any influence over the library, not yet anyway. Meanwhile young Thomas tells his sister, Louisa that he hates his life and everyone except her. He tells her that by now Sissy must hate them all:

‘She must,’ said Tom. ‘She must just hate and detest the whole set-out of us. They’ll bother her head off, I think, before they have done with her. Already she’s getting as pale as wax, and as heavy as—I am.’

He goes on to tell her that he is a donkey saying that he is as obstinate as one, more stupid than one, and that he gets as much pleasure as one. Tom says that he should like to kick like one, everyone but Louisa. Louisa tells him she knows something is missing in her life but she doesn't know what it is:

‘Because, Tom,’ said his sister, after silently watching the sparks awhile, ‘as I get older, and nearer growing up, I often sit wondering here, and think how unfortunate it is for me that I can’t reconcile you to home better than I am able to do. I don’t know what other girls know. I can’t play to you, or sing to you. I can’t talk to you so as to lighten your mind, for I never see any amusing sights or read any amusing books that it would be a pleasure or a relief to you to talk about, when you are tired.’

These poor children, didn't tell ever get to play a game? Tom tells her he will get his revenge when he goes to live with Bounderby. He says his secret of getting what he wants when he leaves home is Louisa herself, she is Bounderby's pet, he tells her, and Bounderby will do anything for her. This makes the future seem so dark for poor Louisa, even if she could withstand Bounderby wanting to marry her - which I think will eventually happen, and her father going along with Bounderby, now she will have Tom to think of. Hopefully some young man will come along and run away with her before any of this can happen. As Louisa looks into the fire telling Tom she is wondering about her and Tom's future, Mrs. Gradgrind overhears her and tells her not to wonder. She goes on to say that they are both inconsiderate of her to even think of doing such a thing. Instead of Sissy coming to live with the Gradgrinds, perhaps things would work out better if Louisa and Tom would have gone to live with her and the circus. This rather depressing chapter ends with this:

‘I was encouraged by nothing, mother, but by looking at the red sparks dropping out of the fire, and whitening and dying. It made me think, after all, how short my life would be, and how little I could hope to do in it.'

‘Nonsense!’ said Mrs. Gradgrind, rendered almost energetic. ‘Nonsense! Don’t stand there and tell me such stuff, Louisa, to my face, when you know very well that if it was ever to reach your father’s ears I should never hear the last of it. After all the trouble that has been taken with you! After the lectures you have attended, and the experiments you have seen! After I have heard you myself, when the whole of my right side has been benumbed, going on with your master about combustion, and calcination, and calorification, and I may say every kind of ation that could drive a poor invalid distracted, to hear you talking in this absurd way about sparks and ashes! I wish,’ whimpered Mrs. Gradgrind, taking a chair, and discharging her strongest point before succumbing under these mere shadows of facts, ‘yes, I really do wish that I had never had a family, and then you would have known what it was to do without me!'

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,Hello all. I'm going to have to make this quick this week, it's lucky I worked ahead. We have twenty inches (thats 50.8 centimeter's if that's any help to anyone) and the wind i..."

Reading this chapter certainly makes you aware of the class system. Bounderby's upward bounce from ditch to dreary bore reflects the concept of the self-made man, as Bounderby consistently enjoys telling everyone. We are told that Bounderby is "a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer." Bounderby, and those like him, were becoming the new wealth and power in Great Britain. The Sparsit and the Powler's were on the decent. Their power, wealth and patronage were no longer a guarantee of position and privilege. To have Mrs. Sparsit as a housekeeper and the ditch-born Bounderby in reverse roles of servant and master in society is a very clear example of how the tables have turned because of the industrial revolution.

It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind, a type of companion for Louisa, and, perhaps even worse, to function as a human educational experiment to turn a young imaginative carefree child into an exemplar of Benthamite theory. poor Sissy. At school is Mr. M'Choakumchild and at her new home a sick, feeble woman, a stern guardian and two repressed children.

It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind, a type of companion for Louisa, and, perhaps even worse, to function as a human educational experiment to turn a young imaginative carefree child into an exemplar of Benthamite theory. poor Sissy. At school is Mr. M'Choakumchild and at her new home a sick, feeble woman, a stern guardian and two repressed children.

Kim wrote: "‘And yet, sir,’ he would say, ‘how does it turn out after all? Why here she is at a hundred a year (I give her a hundred, which she is pleased to term handsome), keeping the house of Josiah Bounderby of Coketown!""

Kim wrote: "‘And yet, sir,’ he would say, ‘how does it turn out after all? Why here she is at a hundred a year (I give her a hundred, which she is pleased to term handsome), keeping the house of Josiah Bounderby of Coketown!""A hundred a year actually was quite handsome. Quite. According to Daily Life in Victorian England a London housekeeper would expect to make between 20 and 45 pounds a year, and the higher rate would be for a large household with many servants to oversee and a large house to be responsible for. Plus wages were normally higher in London than in the towns. So I would have expected Mrs. Sparsit to be paid more in the range of 25-30 pounds. Is Bounderby really paying her that much, or is he exaggerating by a considerable amount? (I guess part of the answer is how honest he turns out to be about other aspects of his life. Is he an honest and accurate autobiographer? )

Peter wrote: "To have Mrs. Sparsit as a housekeeper and the ditch-born Bounderby in reverse roles of servant and master in society is a very clear example of how the tables have turned because of the industrial revolution. ."

Peter wrote: "To have Mrs. Sparsit as a housekeeper and the ditch-born Bounderby in reverse roles of servant and master in society is a very clear example of how the tables have turned because of the industrial revolution. ."A very nice point. Dickens isn't subtle about it, either, but pounds it home like a railway builder pounding home a railroad tie spike.

Everyman wrote: "A very nice point. Dickens isn't subtle about it, either, but pounds it home like a railway builder pounding home a railroad tie spike.."

Everyman wrote: "A very nice point. Dickens isn't subtle about it, either, but pounds it home like a railway builder pounding home a railroad tie spike.."When Dickens wants to bring home a certain point, he hardly ever is especially subtle about it but makes sure the reader will understand him. Just think of the Heeps' mantra of being so very 'umble, or of the narrator introducing Mr. Squeers by saying that he only had one eye and the current bias runs in favour of two and other such things. In the case of Bounderby, however, this lack of subtlety seems quite appropriate since Boundery himself is not exactly a paragon of subtlety, either ;-)

Maybe, Dickens sometimes decided to pile it on because he was writing in instalments and his readers might forget certain details in between instalment numbers, and therefore he had to make them remember?

Peter wrote: "It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind"

Peter wrote: "It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind"I don't really know, Peter. Mr. Gradgrind is apparently not a downright selfish character - even Louisa says that her father is a gentle and caring person, somewhere in Chapter 8 - and I can imagine that he feels compassionate towards Sissy when he learns that her father has abandoned her, and that his school is her only chance to improve her station in life. Mr. Childers also said that it would be becoming in Mr. Gradgrind to do something for Sissy, and he decided to take her up, after originally having wanted to throw her out of the school, although Mr. Bounderby strongly advised him to stick to his original plan. So maybe his motives are not merely selfish, but I don't know for sure.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind"

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "It seems that Gradgrind's offer to take Sissy into his home is not altruistic but rather to secure an unpaid servant for Mrs. Gradgrind"I don't really know, Peter. Mr. Gradgrind is ..."

Yes. I think Dickens is leaving the door open for us. Gradgrind's character certainly reflects his name very well but there is definitely a bit of sunlight in him showing through some very dark clouds.

More to come ...

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,Hello all. I'm going to have to make this quick this week, it's lucky I worked ahead. We have twenty inches (thats 50.8 centimeter's if that's any help to anyone) an..."

I agree Peter. Sad by true. Being brought up in an area at the heart of the Industrial Revolution, and having ancestors who were caught up in it, it brings it close to home.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "To have Mrs. Sparsit as a housekeeper and the ditch-born Bounderby in reverse roles of servant and master in society is a very clear example of how the tables have turned because of t..."

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "To have Mrs. Sparsit as a housekeeper and the ditch-born Bounderby in reverse roles of servant and master in society is a very clear example of how the tables have turned because of t..."Absolutely Everyman. Dickens' voice is loud and clear.

He's also making those who have rose up the ranks, sound cunning, greedy and even a bit mislead (or that's what I'm understanding). Perhaps this is a true characterisation, after all. For how many years were the serfs dominated and taken advantage of. If anyone had the opportunity to make personal gain from the industrial revolution, I'm sure many did with disdain as they passed their once masters on the class system.

All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interesting and also hard to believe is that Bounderby is apparently a well-accepted and highly-esteemed man in Coketown. In Chapter 7 the narrator says,

All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interesting and also hard to believe is that Bounderby is apparently a well-accepted and highly-esteemed man in Coketown. In Chapter 7 the narrator says,"Nay, he made this foil of his so very widely known, that third parties took it up, and handled it on some occasions with considerable briskness. It was one of the most exasperating attributes of Bounderby, that he not only sang his own praises but stimulated other men to sing them. There was a moral infection of clap-trap in him. Strangers, modest enough elsewhere, started up at dinners in Coketown, and boasted, in quite a rampant way, of Bounderby. They made him out to be the Royal arms, the Union-Jack, Magna Charta, John Bull, Habeas Corpus, the Bill of Rights, An Englishman’s house is his castle, Church and State, and God save the Queen, all put together."

So they actually join him in singing his own praise. I was wondering why people might do this instead of turning their backs on a self-important bore like Bounderby.

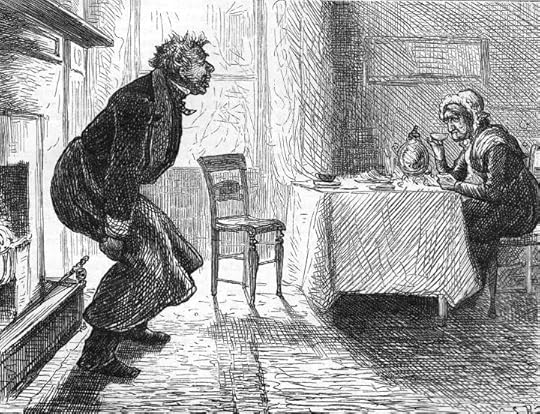

Here is an illustration for this installment by Charles S. Reinhart:

Here is an illustration for this installment by Charles S. Reinhart:

"You were in the tiptop fashion, and all the rest of it,' said Mr. Bounderby."

Chapter 7

C. S. Reinhart

Here's the commentary, but I had to cut a lot of it because it gives away too much of the plot:

"Josiah Bounderby, self-made millionaire industrialist of Coketown, glories in the fact that he has risen from the gutter and now owns a factory and a bank, and is the patron of the "bank fairy," a widow of aristocratic lineage, Mrs. Sparsit. Here, in her elegantly furnished rooms which he has, in his arrogant charity and bullying humility, provided her above the bank, Bounderby warms himself against a roaring coal fire, indicative of conspicuous comsumption, as he puts Mrs. Sparsit in her place as a former social superior over whom he asserts his moral and fiscal hegemony as a successful capitalist and entrepreneur from the rising middle classes. As the scene begins, and Mrs. Sparsit presides over the breakfast tea-pot, Bounderby announces his intention to take young Tom Gradgrind into his office after he has finished "his educational cramming". That he corrects Mrs. Sparsit when she calls Louisa "little puss" alerts the reader to Bounderby's considering as a potential wife.

But so much of what see here is pure artistic invention: the laden tea table in the background, the rich dressing gown and tousled hair of Bounderby, the poker and fender of the fireplace all contribute to a more informed reading of Dickens's text.

The passage illustrated, given the specificity of Reinhart's caption and Bounderby's posture before the fire, is likely this:

"Well, ma'am," said her patron, "perhaps some people may be pleased to say that they do like to hear, in his own unpolished way, what Josiah Bounderby of Coketown has gone through. But you must confess that you were born in the lap of luxury, yourself. Come ma'am, you know you were born in the lap of luxury."

"I do not, sir," returned Mrs Sparsit with a shake of her head, "deny it."

Mr. Bounderby was obliged to get up from the table, and stand with his back to the fire, looking at her; she was such an enhancement of his position.

"And you were in crack society. Devilish high society," he said, warming his legs.

"It is true, sir," returned Mrs. Sparsit, with an affectation of humility the very opposite of his, and therefore in no danger of jostling it.

"You were in the tip-top fashion, and all the rest of it," said Mr. Bounderby.

"Yes, sir," returned Mrs. Sparsit, with a kind of social widowhood upon her. "It is unquestionably true."

Mr. Bounderby, bending himself at the knees, literally embraced his legs in his great satisfaction, and laughed aloud."

Here is what Sol Eytinge, Jr. thinks of Chapter 7, the same scene:

Here is what Sol Eytinge, Jr. thinks of Chapter 7, the same scene:

"Mr. Bounderby and Mrs. Sparsit,"

Chapter 7

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Illustration for The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge and Hard Times 1867

Commentary:

"In this third full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, the penniless aristocrat, Mrs. Sparsit, pours tea for her rough-and-ready employer, the capitalist Josiah Bounderby of Coketown, in her rooms above Bounderby's bank. According to Dickens's descriptions of the pair in chapter 7, Bounderby enjoys displaying Mrs. Sparsit as a sort of trophy, a testimonial to his "up-from-the-gutter" determination to succeed.

The moment realized by Eytinge in the seventh chapter, utilizing material on Bounderby from chapter four, is this:

MR. BOUNDERBY being a bachelor, an elderly lady presided over his establishment, in consideration of a certain annual stipend. Mrs. Sparsit was this lady's name; and she was a prominent figure in attendance on Mr. Bounderby's car, as it rolled along in triumph with the Bully of humility inside. . . .

If Bounderby had been a Conqueror, and Mrs. Sparsit a captive Princess whom he took about as a feature in his state-processions, he could not have made a greater flourish with her than he habitually did. Just as it belonged to his boastfulness to depreciate his own extraction, so it belonged to it to exalt Mrs. Sparsit's. In the measure that he would not allow his own youth to have been attended by a single favorable circumstance, he brightened Mrs. Sparsit's juvenile career with every possible advantage, and showered wagon-loads of early roses all over that lady's path. "And yet, sir," he would say, "how does it turn out after all? Why here she is at a hundred a year (I give her a hundred, which she is pleased to term handsome), keeping the house of Josiah Bounderby of Coketown!"

Although the lady of the Coriolanian eyebrows has only just appeared in the text, Eytinge is assuming that the reader will compare his image of the blustering factory-owner, Josiah Bounderby, with that which Dickens gives in ch. 4:

NOT being Mrs. Grundy, who was Mr. Bounderby?

Why, Mr. Bounderby was as near being Mr. Gradgrind's bosom friend, as a man perfectly devoid of sentiment can approach that spiritual relationship towards another man perfectly devoid of sentiment. So near was Mr. Bounderby — or, if the reader should prefer it, so far off.

He was a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer, and what not. A big, loud man, with a stare, and a metallic laugh. A man made out of a coarse material, which seemed to have been stretched to make so much of him. A man with a great puffed head and forehead, swelled veins in his temples, and such a strained skin to his face that it seemed to hold his eyes open, and lift his eyebrows up. A man with a pervading appearance on him of being inflated like a balloon, and ready to start. A man who could never sufficiently vaunt himself a self-made man. A man who was always proclaiming, through that brassy speaking-trumpet of a voice of his, his old ignorance and his old poverty. A man who was the Bully of humility.

In light of these passages excerpted from the novel's early chapters, how well has Eytinge captured the essence of these antagonists? The angular, somewhat masculine-visaged Mrs. Sparsit in respectable widow's hat and weeds contrasts her porcine employer in starched shirt front and sober business-suit. In particular, Eytinge emphasizes Mrs. Sparsit's sharp chin and nose, which features complement the rounded nose and enormous chin — with neck overflowing the starched collar &mdash of the man who believes himself the synthesis of such British national icons as "the Union-Jack, Magna Carta, and John Bull". Indeed, Eytinge has made his "Bully of Humility" a species of John Bull in the garb of a nineteenth-century bourgeois capitalist."

Kim wrote: "Here is what Sol Eytinge, Jr. thinks of Chapter 7, the same scene:

Kim wrote: "Here is what Sol Eytinge, Jr. thinks of Chapter 7, the same scene:"Mr. Bounderby and Mrs. Sparsit,"

Chapter 7

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Illustration for The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge a..."

Kim

Thanks for the research into the illustrations.

Is it me or does Eytinge make Mrs. Sparsit look rather masculine? While it's hard to admit this, Kyd's conception of Mrs. Sparsit rings more true in my mind's eye.

Oh, how I miss H.K. Browne's illustrations.

Tristram wrote: "All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interestin..."

Tristram wrote: "All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interestin..."Hmmm... but I'm mulling over the narrator's comment, "there was a moral infection of clap-trap in him".

I'm not sure if it's just an English slang word, but 'clap-trap' basically means what someone is saying is exaggerated or not true. So perhaps people didn't believe him, rather they were just allowing him to get away with his own theatrics so they could follow suit. If he could get away with it, then they could get away with doing it too, or perhaps they let him because it made their lower ranks look better than it would without boastful people like Bounderby. This, at least, is what I make out of comment "moral infection of clap-trap".

Tristram wrote: "All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interestin..."

Tristram wrote: "All of us seem to be quite critical of Bounderby and would probably do their best to avoid him in real life in order to be spared having to listen to his endless boasting but what I find interestin..."Hmmm. From your writing, I couldn't help thinking about a politician currently running for our Presidency. I don't think I need to give a name.

Kim wrote: "And this is how Kyd pictured Mrs. Sparsit:

Kim wrote: "And this is how Kyd pictured Mrs. Sparsit:"

I am through with Kyd. Not a single illustration of his has been anything even remotely like my interior picture of these people.

A Coriolanian nose has nothing to do with the color of the nose -- it's not a read nose, it's more of an aristocratic hooked nose. And where does he get the idea that she is a glowering highly unattractive woman? Where is her "dignity serenely mournful"? Where is her " affectation of humility"? Is this the picture of a woman who was "in tip-top fashion" and has an "affectation of humility"?

Bah. Humbug.

Kyd, get the gone.

I will go with Everyman in his criticism of Kyd: When I first looked at Kyd's illustration of Mrs. Sparsit, I could not help thinking that instead of drawing an aristocratic woman he drew a female drunkard or a woman who is suffering from a chronic case of the sniffles. Eytinge's nose (at least the nose he gave to Mrs. Sparsit) is what I would call Coriolanian. We should not forget that Coriolanus was a Roman general and as such could not very well have had a conspicuously red nose, which would have marked him out too clearly in the fray of the battle and provided a good aim for any archer ready to pick the enemy general from his horse.

I will go with Everyman in his criticism of Kyd: When I first looked at Kyd's illustration of Mrs. Sparsit, I could not help thinking that instead of drawing an aristocratic woman he drew a female drunkard or a woman who is suffering from a chronic case of the sniffles. Eytinge's nose (at least the nose he gave to Mrs. Sparsit) is what I would call Coriolanian. We should not forget that Coriolanus was a Roman general and as such could not very well have had a conspicuously red nose, which would have marked him out too clearly in the fray of the battle and provided a good aim for any archer ready to pick the enemy general from his horse.For that matter, I would either go with Eytinge - who dwells on the aristocratic side of Mrs. Sparsit - or, less enthusiastically with Reinhart, whose Mrs. Sparsit is more clearly an example of a once proud woman who has been humbled in life.

Thanks again, Kim, for giving us those interesting illustrations!

Kate wrote: "Hmmm... but I'm mulling over the narrator's comment, "there was a moral infection of clap-trap in him"."

Kate wrote: "Hmmm... but I'm mulling over the narrator's comment, "there was a moral infection of clap-trap in him"."You are right, Peter, the clap-trap statement is not to be ignored, and I like your interpretation of people putting up with Mr. Bounderby's boasting so that they could follow suit with impunity.

Maybe they also put up with Mr. Bounderby's love songs to himself because they seem to prove a point that was dear to Social Darwinism - namely that life is a battle and that even those who are poor and uneducated can make their way up in life if only they try hard enough so that there is no real need to instal social welfare measures and look after the poor.

Tristram wrote: "I will go with Everyman in his criticism of Kyd: When I first looked at Kyd's illustration of Mrs. Sparsit, I could not help thinking that instead of drawing an aristocratic woman he drew a female ..."

Tristram wrote: "I will go with Everyman in his criticism of Kyd: When I first looked at Kyd's illustration of Mrs. Sparsit, I could not help thinking that instead of drawing an aristocratic woman he drew a female ..."You two have me laughing with your criticisms of Kyd and his Mrs. Sparsit. Why, you almost have me wanting to say "Poor Kyd", almost but not quite, I don't think I've ever seen an illustration of his that looked like the character it was supposed to be.

I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long and not specific to various remarks.

I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long and not specific to various remarks. My overall musings in chapter 7 was on the Nature vs. Nurture question. What were Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrinds' parents and childhoods like? Did Mrs. Gradgrind never love a doll? How on earth did these two people even find each other?

But let's accept them at face value. Even if they're the fact-based, pathetic couple Dickens paints them to be, doesn't nature come in somewhere? Even the disgraceful Harlow monkey experiments proved that a baby monkey craves something warm to turn to, even if it's just a board in a blanket. Tom and Louisa are inclined to love, wonder, be faniciful; they even seem to realize that this fact-based reality is unnatural. To some extent they seem to turn to one another with their affection, but I guess it's been drilled into them for so long that this is somehow wrong, that they are afraid to admit that they have hopes, dreams, curiosity. How will they, in turn, raise their children?

The closest fictional character I can equate this family to is Doc Martin, who also had a cold, clinical upbringing, deals in facts alone, and seems to have no sense of whimsy. How bleak.

The remarks about Sissy earning her keep by serving Mrs. Gradgrind bring to mind the orphan trains from the turn of the century. Children were shuttled West where they were adopted by whoever would take them, pretty much. Some undoubtedly went to good homes and were loved. Others were nothing more than farm hands or household help. Still others undoubtedly had other horrors to live through. Remember Anne of Green Gables? Miranda was upset that they'd mistakenly been sent a girl, when they wanted a boy to do some of the heavy lifting. So whether Gradgrind proves to be kind and magnanimous or not, it doesn't seem unusual that he'd expect Sissy to earn her keep.

Why did others in Cokestown also tout Bounderby's rise from the gutter? The only thing I can think is that Bounderby's money, as is always the case, brings him power. With money and power come sycophants, as well as the desire of people to want to get close, or at least give the appearance that they are.

I love the drawing of Bounderby at the fire. As I read that passage, I was picturing this image: "Mr. Bounderby, bending himself at the knees, literally embraced his legs in his great satisfaction, and laughed aloud." What an odd thing for Dickens to imagine! I agree that Kyd's interpretation of Mrs. Sparsit is off the mark. I never pictured her as being so bitter and angry looking, though Lord knows she has every reason to be!

Kim wrote: "she can't be ignorant if she can read"

Kim wrote: "she can't be ignorant if she can read"Oh, I don't know Kim.... I've known a lot of people who can read but are plenty ignorant of a great number of things!

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long ..."I have just finished reading a book on orphan trains. What a horror!

Peter wrote: "I have just finished reading a book on orphan trains. What a horror! "

Peter wrote: "I have just finished reading a book on orphan trains. What a horror! "Well, yes, but the orphanages were also terrible. If the orphans wound up with a good family, especially one on a successful farm, they could be in a much better position, get enough food and fresh air and exercise. Yes, it was hard, but of the choices for some I think it was the better. But for others, of course, like Oliver Twist, very much not so.

I'm intrigued by Mrs. Sparsit's character and what motivates her. Why did she allow Lady Scadgers to arrange her marriage to a man "just of age", who was 15 years younger than herself and already in debt? Did she think she could control him, or his spending? I enjoyed the details that they separated soon after the honeymoon, and when widowed, Mrs. Sparsit had a "deadly feud" with Lady Scadgers and, partly to "spite her Ladyship", became a housekeeper. She has a rebellious streak (shades of Aunt Betsey from DC, perhaps, though I suspect not as good-hearted) and similar to Bounderby, is faking humility, although in a much more subtle way. Perhaps in some respects she feels she has the upper hand of Bounderby; certainly she is not keen on his marital designs toward Louisa. Regarding her Coriolanian nose, my edition notes that the Roman general "was (especially in light of Shakespeare's portrayal of him in 'Coriolanus'), associated with an excessive amount of pride". I think that could describe both her and her employer. (Great eyebrows, too!)

I'm intrigued by Mrs. Sparsit's character and what motivates her. Why did she allow Lady Scadgers to arrange her marriage to a man "just of age", who was 15 years younger than herself and already in debt? Did she think she could control him, or his spending? I enjoyed the details that they separated soon after the honeymoon, and when widowed, Mrs. Sparsit had a "deadly feud" with Lady Scadgers and, partly to "spite her Ladyship", became a housekeeper. She has a rebellious streak (shades of Aunt Betsey from DC, perhaps, though I suspect not as good-hearted) and similar to Bounderby, is faking humility, although in a much more subtle way. Perhaps in some respects she feels she has the upper hand of Bounderby; certainly she is not keen on his marital designs toward Louisa. Regarding her Coriolanian nose, my edition notes that the Roman general "was (especially in light of Shakespeare's portrayal of him in 'Coriolanus'), associated with an excessive amount of pride". I think that could describe both her and her employer. (Great eyebrows, too!)

Mary Lou wrote: "Why did others in Cokestown also tout Bounderby's rise from the gutter? The only thing I can think is that Bounderby's money, as is always the case, brings him power. ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Why did others in Cokestown also tout Bounderby's rise from the gutter? The only thing I can think is that Bounderby's money, as is always the case, brings him power. ..."I would add to everyone's suggestions that Bounderby represents a successful rags-to-riches story (albeit exaggerating the rags portion), and those in the lower classes needed to believe in the story. If a braggart like Bounderby can succeed, perhaps they might improve their lots too. I'm detecting some potential snobbery toward social climbing in Dickens again...

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I have just finished reading a book on orphan trains. What a horror! "

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I have just finished reading a book on orphan trains. What a horror! "Well, yes, but the orphanages were also terrible. If the orphans wound up with a good family, especially one on..."

Do we still have orphanages? I haven't seen one in years, perhaps they are all closed or called something else. And if they closed where do the orphaned children go now?

Kim wrote: "Do we still have orphanages? "

Kim wrote: "Do we still have orphanages? "In the US, at least, I think it's all foster care. That's hit and miss, too -- just read something yesterday about a child being abused in his foster home.

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know why, but I never get notifications when we start a discussion of a new section and, therefore, always have a lot of catching up to do on comments! So please forgive me if this is long ..."Mary Lou

I am not whiz when it comes to technology but I wonder if the reason you are not getting the notifications is because you have not pressed/enabled the "button" that is on the right top corner of this response comment box. It will read "You are following this discussion" when pressed.

Did what I say make any sense or help? I don't know how to explain it any better. Sorry.

Peter wrote: "I wonder if the reason you are not getting the notifications is because you have not pressed/enabled the "button" that is on the right top corner of this response comment box. It will read "You are following this discussion" when pressed."

Peter wrote: "I wonder if the reason you are not getting the notifications is because you have not pressed/enabled the "button" that is on the right top corner of this response comment box. It will read "You are following this discussion" when pressed."Thanks, Peter -- I do have that checked. I don't get anything telling me about a new thread when we start a new chapter discussion. But once I remember to find it and add a comment, I start getting the notifications. The good news is that if I'm enjoying a book and looking forward to the conversation, it's much easier to remember to log in and find it!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I wonder if the reason you are not getting the notifications is because you have not pressed/enabled the "button" that is on the right top corner of this response comment box. It will..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I wonder if the reason you are not getting the notifications is because you have not pressed/enabled the "button" that is on the right top corner of this response comment box. It will..."I find that the easiest way to find new things is to use the "unread" link which appears at the top of the Discussions page. Go to Discussions from the main menu and just above the topics on the right is a line that says "new topic | edit folders | unread"

Click on read and it will bring up all the folders that have messages you haven't read yet, and the number of unread posts in red. Click on the red number and it will take you to the first unread post.

If there are a ton of unread posts when you first do this, read what you are interested in and then click on the "mark all as read" on the bottom of the list of folders with unread messages. For new groups I often have to do this several times to clear everything out, and it isn't perfect, but it works pretty well. After awhile the "unread" option works fine to give you just those posts that are new to you, including folders that have just been created.

Everyman wrote: "I find that the easiest way to find new things is to use the "unread" link which appears at the top of the Discussions page."

Everyman wrote: "I find that the easiest way to find new things is to use the "unread" link which appears at the top of the Discussions page."That's a link I never noticed, Everyman. Thanks for the tip!

As usual, reading your contributions made me aware of questions I don't know the answers to - are there still orphanages or is it all done via foster parents - and of things I had as yet not heard about - I will have to look up what "orphan trains" were.

As usual, reading your contributions made me aware of questions I don't know the answers to - are there still orphanages or is it all done via foster parents - and of things I had as yet not heard about - I will have to look up what "orphan trains" were.As to the high-tech stuff: I don't get a notification when Kim starts a new thread - of course, neither do I get one when I do so - but whenever the first person replies to the opening post, then I am notified. All in all, however, I find it quite easy to manoeuvre on GR and to find my way around. Nevertheless, if I fail to answer a post directed to me, rest assured that this will be an oversight and is not prompted by Dombeyism ;-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Why did others in Cokestown also tout Bounderby's rise from the gutter? The only thing I can think is that Bounderby's money, as is always the case, brings him power. With money and power come sycophants, as well as the desire of people to want to get close, or at least give the appearance that they are."

Mary Lou wrote: "Why did others in Cokestown also tout Bounderby's rise from the gutter? The only thing I can think is that Bounderby's money, as is always the case, brings him power. With money and power come sycophants, as well as the desire of people to want to get close, or at least give the appearance that they are."I also asked myself why other Coketowners should join Mr. Bounderby in singing his praise - but maybe they were quite happy about a selfmade-man like Bounderby who lent himself as an example of Social Darwinist theories. "If only you try hard enough", these people might say to malcontent workers, "you may also succeed as Mr. Bounderby did. Mr. Bounderby was even worse off than you, and still look where he is now." So in singing Mr. Bounderby's praise, Coketown officials might be able to justify their neglect of social issues.

Mary Lou wrote: "My overall musings in chapter 7 was on the Nature vs. Nurture question. What were Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrinds' parents and childhoods like? Did Mrs. Gradgrind never love a doll? How on earth did these two people even find each other?"

Mary Lou wrote: "My overall musings in chapter 7 was on the Nature vs. Nurture question. What were Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrinds' parents and childhoods like? Did Mrs. Gradgrind never love a doll? How on earth did these two people even find each other?"The Nature vs. Nurture question indeed comes foremost into mind when one thinks of Gradgrind and his pedagogical principles. It is very difficult to imagine Gradgrind as a child but if you take a child with anancastic traits - whether they be inherited or a product of education - you might already have your Gradgrind in nuce. If I consider Gradgrind's apparent readiness to marry his daughter to someone like Bounderby, I can also understand how Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrind might have found, or be made to find, each other, despite their apparent lack of feeling. By the way, I would not regard Mrs. Gradgrind as devoid of sentiment at all; she just seems like a rather depressed woman who lives under the impression that everyone around her is more educated than she, and that is why she might be given to the occasional outburst against her children and to a rather pervading tendency to make herself invisible. In fact, she is a woman to be pitied.

Vanessa wrote: "I'm detecting some potential snobbery toward social climbing in Dickens again... "

Vanessa wrote: "I'm detecting some potential snobbery toward social climbing in Dickens again... "With regard to Bounderby, you certainly have a point there - and we saw a similar reservation on Dickens's side in David Copperfield when the narrator made it clear how the other factory boys instinctively realized that he was of a different social class and therefore abstained from being too familiar. Uriah Heep is another example of the bad social climber. I am afraid there will be more examples in some of the works we are going to read.

Tristram wrote: "The Nature vs. Nurture question indeed comes foremost into mind when one thinks of Gradgrind and his pedagogical principles. It is very difficult ..."

Tristram wrote: "The Nature vs. Nurture question indeed comes foremost into mind when one thinks of Gradgrind and his pedagogical principles. It is very difficult ..."All good points. And in the "I learned something new today" category, I had to look up "anancastic" and "in nuce" - my brain thanks you. :-)

Vanessa,

Vanessa,I am also very curious as to the further role of Mrs. Sparsit. I would account for her hapless marriage by thinking that she might have trusted to her great-aunt's good judgment and that on finding her sense of judgment so utterly deficient, Mrs. Sparsit might really have enjoyed taking a position as a housekeeper to spite her great-aunt.

All the more so as Mrs. Sparsit probably really knows how to keep the upperhand in the house of Bounderby; just consider this little detail:

"‘Indeed? Rather young for that, is he not, sir?’ Mrs. Sparsit’s ‘sir,’ in addressing Mr. Bounderby, was a word of ceremony, rather exacting consideration for herself in the use, than honouring him."

She indeed seems to be the very person someone like Bounderby deserves.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The Nature vs. Nurture question indeed comes foremost into mind when one thinks of Gradgrind and his pedagogical principles. It is very difficult ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The Nature vs. Nurture question indeed comes foremost into mind when one thinks of Gradgrind and his pedagogical principles. It is very difficult ..."All good points. And in the ..."

So we learn all from each other - and at the same time discuss one of our favourite authors. A classical win-win-situation!

Mary Lou wrote: "All good points. And in the "I learned something new today" category, I had to look up "anancastic" and "in nuce" - my brain thanks you. :-) "

Mary Lou wrote: "All good points. And in the "I learned something new today" category, I had to look up "anancastic" and "in nuce" - my brain thanks you. :-) "Oh great, now that you pointed out that Tristram is once again using words I've never heard before - or read before - I must go look them up, again. The trouble with me is my brain doesn't thank him, I'll forget what they mean by next weekend. :-)

Hmm.....well the first definition cleared the whole thing up for me, I'm so glad I took the time to look:

an·an·cas·tic

(an'an-kas'tik),

Pertaining to anancasm or anancastia.

Moving on to in nuce:

From in + nuce the ablative singular of nux meaning "nut". Literally meaning "in a nut".

Adverb

in nuce

1.in a nutshell; briefly stated

2.in the embryonic phase; said of something which is just developing or being developed

Kim wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "All good points. And in the "I learned something new today" category, I had to look up "anancastic" and "in nuce" - my brain thanks you. :-) "

Kim wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "All good points. And in the "I learned something new today" category, I had to look up "anancastic" and "in nuce" - my brain thanks you. :-) "Oh great, now that you pointed out t..."

Just imagine what will happen if Tristram starts using more of those enormous German words. Ouch!

I thank you too, Tristram, for expanding my vocabulary.

I thank you too, Tristram, for expanding my vocabulary. Thank you, Kim, for your definition of anancastic. I now find myself to be truly enlightened. I can now say "The day was anancastic except for a few drops of rain."

"The lady looked anancastic, but I hesitated to point it out."

"What anancastic nonsense that old lady speaks."

Ah learning. ;-)

In regard to 'in nuce', I am a little better informed. Now I have to look up the pronunciation. The Latin we learned bore little resemblance to spoken Latin today or yesterday. We always used a hard 'c' instead of a more Italianate pronunciation AND there was never agreement on the 'v' sound. Did it sound like 'v' or 'w'? Yes, yes it was ancient Latin so 'no one can be sure how it was pronounced.' Indeed, and I'm Pope Francis. ;-)

Yes, I can now use anancastic in a sentence. I just did, without knowing any more than I did about what it means in the first place.

Yes, I can now use anancastic in a sentence. I just did, without knowing any more than I did about what it means in the first place.

Hilary,

Hilary,if you wanted to make our Latin teacher really, really mad, all you had to do was pronounce the c as an s and not as a k. Our Latin teacher was a portly little man, always dressed in white or beige suits, with a helmet of white hair on his head. Only in the front, there was a streak of yellow because whenever he could, he would smoke a cigarette, and the smoke had coloured his hair. He spoke at least a dozen of languages fluently, maybe more, among those even Arabic, Hebrew and Russian and he was clearly undertaxed with us pupils. That's why he would simply spend some part of his morning in a nearby café, reading international papers, drinking coffee and smoking - instead of teaching. We were his partners in crime in that we would not report the absence of our teacher but just keep quiet.

When two or three or more of us would not be able to tackle with a particularly nasty specimen of the ablativus absolutus, he would sometimes go to the window, tap with his fingers on the window sill, look out and say with an ominous voice (the capitalized words would have been shouted at us), "One of these days, there will be a giant ARSE lowering itself from Heaven and SH*T on this WHOLE school!"

Non scholae, sed vitae discimus!

Tristram wrote: "Hilary,

Tristram wrote: "Hilary,if you wanted to make our Latin teacher really, really mad, all you had to do was pronounce the c as an s and not as a k. Our Latin teacher was a portly little man, always dressed in white ..."

How could you tell he was really speaking a dozen languages? After English he could have just been making up stuff and telling me it was Arabic, Hebrew and Russian and I would have had to take his word for it.

Oh, I had to look up Non scholae, sed vitae discimus, which ended up being pretty simple "We do not learn for school, but for life" according to google, although it would have been much simpler for a certain person to just use English in the first place. Then I looked up ablativus absolutus which ended up being more difficult. First I got only German sites, so after translating one the definition I got - the first paragraph anyway was:

"The ablative absolute (also briefly Abl abs.. Called; also ablative with participle or ablative with Praedicativum (AMP / AcP)) is a Latin participle, which usually consist of a noun and a participle each in ablative there and in German has no direct equivalent , The ablative absolute takes the place of a subordinate clause, whereby only the temporal relationship is given to the parent set - the more logical link needs from the context to be tapped."

I suppose I could have gone on, but I didn't.

Hello all. I'm going to have to make this quick this week, it's lucky I worked ahead. We have twenty inches (thats 50.8 centimeter's if that's any help to anyone) and the wind is getting crazy now. The lights are blinking and they are telling us on the news to expect our power to go out so I'll expect it to go out, be glad I worked a little ahead on this, and post it now. Oh, and I love it all in case you are wondering. :-)

This week's installment begins with Chapter 7 titled " Mrs. Sparsit" and the chapter opens with that very lady being introduced to us as Mr. Bounderby's housekeeper. I'm not sure how much money she made for this, but it wasn't enough. Mr. Bounderby seems to greatly enjoy having Mrs. Sparsit as his housekeeper, since as we all know he grew up in a ditch, a very deep ditch, and apparently Mrs. Sparsit came from a rather well-off family. Dickens tells us that Mrs. Sparsit is "a prominent figure in attendance on Mr. Bounderby’s car, as it rolled along in triumph with the Bully of humility inside." Mrs. Sparsit had seen better days, many of them if she now works for Bounderby, and is even highly connected having a great aunt still living named Lady Scadgers. She was also from the Powler family, which a better class of minds knew were an ancient stock, another high connection. However her husband had lost their fortune long ago and died when he was only twenty-four. And now in her elderly days her she is working for Bounderby, " with the Coriolanian style of nose and the dense black eyebrows which had captivated Sparsit."

Oh, I looked up Coriolanian style and got this answer:

"Of or relating to Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, Roman general said to have lived in the 5th century BC, famed for exceptional valour."

It seems Bounderby loves having Mrs. Sparsit as his housekeeper because he loves reminding her, and everyone else in town and us of their different positions in life:

"If Bounderby had been a Conqueror, and Mrs. Sparsit a captive Princess whom he took about as a feature in his state-processions, he could not have made a greater flourish with her than he habitually did. Just as it belonged to his boastfulness to depreciate his own extraction, so it belonged to it to exalt Mrs. Sparsit’s. In the measure that he would not allow his own youth to have been attended by a single favourable circumstance, he brightened Mrs. Sparsit’s juvenile career with every possible advantage, and showered waggon-loads of early roses all over that lady’s path. ‘And yet, sir,’ he would say, ‘how does it turn out after all? Why here she is at a hundred a year (I give her a hundred, which she is pleased to term handsome), keeping the house of Josiah Bounderby of Coketown!"

I wonder why Bounderby acts the way he does, especially talks the way he does. Is he really so proud of his humble in the ditch beginnings that he has to talk about it to every single person every single time he sees them? Does he think it impresses people, or doesn't he care how people feel about him? And does it impress anyone? I suppose if he went about it the right way he could be an encouragement to those who are not well-to-do, to show them that you can be successful no matter where you begin, but he certainly doesn't seem to be going about it the right way. And is he trying to help anyone or does he just like to hear himself talk?

Bounderby is telling Mrs. Sparsit, when he gets done talking about himself of course, that he doesn't like the idea of Sissy Jupe being in contact with Louisa, or the "little puss" as he calls her. I was amused when Mrs. Sparsit tells him he has always been like a second father to Louisa. He quickly corrects her of course, saying he is more of a father to young Tom and plans to take him into his office one day when his schooling is finished. Poor Tom. After some more of the poor me, lucky you talk he loves to take part of, or rather lecture in, Mr. Gradgrind and Louisa arrive to take Sissy home with them.

I am puzzled a little by this part of the conversation between Mr. Gradgrind and Sissy:

"‘Jupe, I have made up my mind to take you into my house; and, when you are not in attendance at the school, to employ you about Mrs. Gradgrind, who is rather an invalid. I have explained to Miss Louisa—this is Miss Louisa—the miserable but natural end of your late career; and you are to expressly understand that the whole of that subject is past, and is not to be referred to any more. From this time you begin your history. You are, at present, ignorant, I know.’

‘Yes, sir, very,’ she answered, curtseying.

‘I shall have the satisfaction of causing you to be strictly educated; and you will be a living proof to all who come into communication with you, of the advantages of the training you will receive. You will be reclaimed and formed. You have been in the habit now of reading to your father, and those people I found you among, I dare say?’ said Mr. Gradgrind, beckoning her nearer to him before he said so, and dropping his voice.

‘Only to father and Merrylegs, sir. At least I mean to father, when Merrylegs was always there.’

‘Never mind Merrylegs, Jupe,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, with a passing frown. ‘I don’t ask about him. I understand you to have been in the habit of reading to your father?’

‘O, yes, sir, thousands of times. They were the happiest—O, of all the happy times we had together, sir!"

What I didn't understand about this was Gradgrind first saying to her that she is ignorant which she agrees with, but then he knows that she is in the habit of reading to her father. Well she can't be ignorant if she can read, so why would he say it? I'm not surprised with his reaction when she tells him what she reads and I'll close with that.

"‘And what,’ asked Mr. Gradgrind, in a still lower voice, ‘did you read to your father, Jupe?’

‘About the Fairies, sir, and the Dwarf, and the Hunchback, and the Genies,’ she sobbed out; ‘and about—’

‘Hush!’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘that is enough. Never breathe a word of such destructive nonsense any more. Bounderby, this is a case for rigid training, and I shall observe it with interest.’

‘Well,’ returned Mr. Bounderby, ‘I have given you my opinion already, and I shouldn’t do as you do. But, very well, very well. Since you are bent upon it, very well!’

So, Mr. Gradgrind and his daughter took Cecilia Jupe off with them to Stone Lodge, and on the way Louisa never spoke one word, good or bad. And Mr. Bounderby went about his daily pursuits. And Mrs. Sparsit got behind her eyebrows and meditated in the gloom of that retreat, all the evening."