The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Part I Chapters 01 - 03

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Kim wrote: ""American-born but European-trained artist C. S. [Charles Stanley] Reinhart's sixteen plates for Charles Dickens's Hard Times. For These Times appeared in the single-volume, American version of the..."

Kim wrote: ""American-born but European-trained artist C. S. [Charles Stanley] Reinhart's sixteen plates for Charles Dickens's Hard Times. For These Times appeared in the single-volume, American version of the..."Kim:

For the first time this year, and I highly suspect it will be far from the last time, thank you for the additional information you always provide. It is always appreciated.

As we have read through Dickens the illustrations of Cruikshank and Browne have anchored the chapters of the novel. I have grown both used to and fond of them. The many many you have supplied, along with illustrators such as Gorey, Bernard and others have been great to compare both with the originals and each other.

Strangely ( at least to me) is the fact that without Browne's work it is hard to compare or comment on Reinhart or Henry French. Maybe I'm spoiled, maybe I'm too set in my ways.

Tristram wrote: "I can't bring myself to completely dislike Mr. Gradgrind, though, because I think he is really acting from conviction of helping these children to get on in life...."

Tristram wrote: "I can't bring myself to completely dislike Mr. Gradgrind, though, because I think he is really acting from conviction of helping these children to get on in life...."I felt the same, Tristram. Although narrow-minded and inappropriate, he did not come across as intentionally cruel, like David Copperfield's first teacher (Creakle?). Gradgrind and the teacher seemed to be instruments of the government officer, who with his power, and intentions, I found more disturbing.

I wondered if it was just a coincidence that Bitzer, in his horse definition, referred to molars as "grinders"? I hope it was a little rebellion, even a subconscious one, on the part of the star student :)

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "They are like the grand philanthropists of BH, so caught up in their own greatness and purpose they cannot see the destruction they wreak around them. Unintended consequences -- a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "They are like the grand philanthropists of BH, so caught up in their own greatness and purpose they cannot see the destruction they wreak around them. Unintended consequences -- a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit."And no individuality, or subjectivity. I think this is partly why I was dismayed by the government officer, with his belief he could dictate taste, "with a system to force down the general throat". Although it's absurd to think of forbidding all paintings of horses, floral rugs and spode china, etc, his dogmatic bent is unsettling. Gradgrind's renaming of Sissy, reminded me of Canada's residential school system for indigenous people, where children were given numbers and renamed, in a systematic attempt to eradicate their culture and language -- a system that lasted to the mid-20th C.

I also saw a parallel with the obsessiveness of Mrs. Jellyby et al, Xan, and their belief that they act in the best interests of others.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when..."

I join Peter's thanks in providing this background info, Kim. Very interesting to learn that Dickens struggled with the time and space limits. So far, I don't they did justice to his writing :)

Peter, a belated thanks for suggesting we read the opening sections at the same rate as his original readers. It certainly adds another dimension to reading and learning.

Vanessa wrote: " Gradgrind's renaming of Sissy, reminded me of Canada's residential school system for indigenous people"

Vanessa wrote: " Gradgrind's renaming of Sissy, reminded me of Canada's residential school system for indigenous people"On a lighter note, I'm reminded of the old movie "Yours, Mine, and Ours" with Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda. The son wants to use his new stepfather's last name, but the unyielding nun insists he use his legal name. The argument escalates into a classroom brawl.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBxQe...

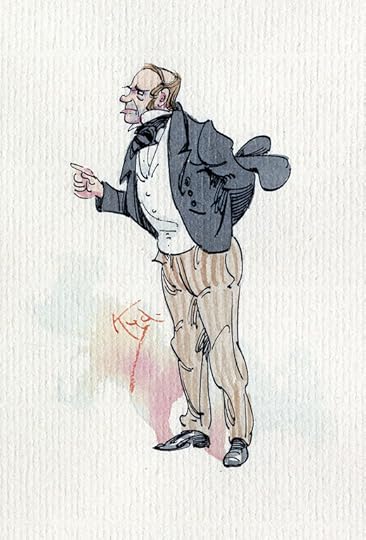

The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, as well as the brow hanging like a portico, and the lack of flexibility in his character. Despite all that, I don't care for it as much. He almost looks as if he should have bolts on the sides of his neck under that cravat, or like you have to flip a switch to animate him.

The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, as well as the brow hanging like a portico, and the lack of flexibility in his character. Despite all that, I don't care for it as much. He almost looks as if he should have bolts on the sides of his neck under that cravat, or like you have to flip a switch to animate him.

Mary Lou wrote: "The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, ... Despite all that, I don't care for it much..."

Mary Lou wrote: "The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, ... Despite all that, I don't care for it much..."Nor do I. It looks more like a waxworks than a person.

From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a look at him, remarkable for its intense and searching character. He saw nothing of it, for before he looked at her, she had again cast down her eyes!"

From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a look at him, remarkable for its intense and searching character. He saw nothing of it, for before he looked at her, she had again cast down her eyes!"What is this foreshadowing?

Everyman wrote: "From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a..."

Everyman wrote: "From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a..."Thank you for reminding me of this. It seems to me that Gradgrind repeated the Bounderby question several times, which would also indicate that it will have some importance down the road.

Kim wrote: "And here is an illustration of Mr, Gradgrind by Sol Eytinge:

Kim wrote: "And here is an illustration of Mr, Gradgrind by Sol Eytinge:Thomas Gradgrind

by Sol Eytinge"

After the viewing of the Kyd and the Eytinge illustrations I have an even greater appreciation for H.K. Browne (Phiz).

Everyman wrote: "From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a..."

Everyman wrote: "From the end of Chapter 3: '‘What would your best friends say, Louisa? Do you attach no value to their good opinion? What would Mr. Bounderby say?’ At the mention of this name, his daughter stole a..."I find Gradgrind's comment very sad. What kind of friends would Louisa and Tom be allowed to have. If they were anything like Bitzer it would be like having no friends at all.

Peter wrote: "I find Gradgrind's comment very sad. What kind of friends would Louisa and Tom be allowed to have. ."

Peter wrote: "I find Gradgrind's comment very sad. What kind of friends would Louisa and Tom be allowed to have. ."Why, friendship isn't in their vocabulary. It's a sensation, or a feeling, not a fact. And not being a fact, it's unworthy of any attention from them at all.

Everyman wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, ... Despite all that, I don't care for it much..."

Everyman wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "The Eytinge sketch better captures the squareness described in the text, ... Despite all that, I don't care for it much..."Nor do I. It looks more like a waxworks than a person."

It's bordering on Frankenstein's monster! Just minus the bolts. Ha ha.

My mental eye pictures Gradgrind as a rather lean man because somebody who entirely lives on Facts will hardly be as portly as the gentleman in the first illustration. I do agree with Peter, on the whole, in saying that Phiz is the Dickens illustrator and that it is difficult to do without him. Nevertheless, I'd like to thank Kim for all the hard work in finding those illustrations and the respective comments. The Gutenberg Project also gives illustrations in its Hard Times text, by the way.

My mental eye pictures Gradgrind as a rather lean man because somebody who entirely lives on Facts will hardly be as portly as the gentleman in the first illustration. I do agree with Peter, on the whole, in saying that Phiz is the Dickens illustrator and that it is difficult to do without him. Nevertheless, I'd like to thank Kim for all the hard work in finding those illustrations and the respective comments. The Gutenberg Project also gives illustrations in its Hard Times text, by the way.

What a hilarious and compelling start to a novel. That description of the boy on the ground straining to get a look at "but a hoof" of the elegant equestrian show :D It's been awhile since a book made me laugh out loud and eager to read on after just a few pages.

What a hilarious and compelling start to a novel. That description of the boy on the ground straining to get a look at "but a hoof" of the elegant equestrian show :D It's been awhile since a book made me laugh out loud and eager to read on after just a few pages. It's not exactly subtle, and I also found the warnings against wallpaper to be a bit eye-rolling, but easily forgiven in light of the liveliness and humour of the writing.

Dee wrote: "What a hilarious and compelling start to a novel. That description of the boy on the ground straining to get a look at "but a hoof" of the elegant equestrian show :D It's been awhile since a book m..."

Dee wrote: "What a hilarious and compelling start to a novel. That description of the boy on the ground straining to get a look at "but a hoof" of the elegant equestrian show :D It's been awhile since a book m..."You are right. The book offers exaggerated humour as well as a rather dark vision of Coketown and we have just started our read. |No doubt Dickens will have much more up his sleeve.

OK, I've finally taken the time to read through all 71 messages and I am going to get caught up with the group as far as the reading goes tonight.

OK, I've finally taken the time to read through all 71 messages and I am going to get caught up with the group as far as the reading goes tonight.Tristram, thank you for the nice summary, as I needed a reminder of what I had read two weeks ago.

Kim, thank you for the excerpt from John Forster to give us an insight into Dickens' struggles with writing within a shorter space. Although I love Dickens’ long, meandering descriptions of settings and characters, I must admit that I didn’t miss having those long descriptions here. Perhaps it has to do with my absence from reading his work for a few months, so just getting the feel for his writing again is nice to delve back into.

As for the illustrations, I again miss having those in my book (my copy of DC didn’t include them) and I didn’t realize that they were not done along with the original installments until mentioned in the threads here. My gut reaction to the illustrations Kim posted was that the first one by Henry French resembles most closely what I had imagined while reading. I completely agree with Mary Lou’s assessment of the Eytinge illustration in post 61, although he appears all squared off, he also seems to be missing some side neck bolts! And Kyd’s illustrations, well, they are always good for a couple of raised eyebrows. Even when his illustrations look OK enough to match Dickens’ descriptions, they never really look Dickensian to me.

I think my favorite bit was the wallpaper lesson. And I had to think a bit about the question regarding having flowers on the carpet (I would have gotten it “wrong”). I also loved the boy saying he would paint the wall instead, like Vanessa pointed out, he is questioning the question. “Girl number 20” also made me laugh, and although I found it humorous, it is a sad way of grouping all the students together as fact-receptacles instead of children with individual minds and names.

Everyman, thank you for reminding me of the passage regarding Louisa’s “stolen look” at her father with “intense and searching character” and then looking away before he could see. I also wondered what this scene might be foreshadowing.

As to what the Pickwickians will do once we reach the end, I’m raising my hand for looping back to the beginning as I only joined the group with Dombey and Son. I've yet to read anything by Gaskell and would be up for that as well. But, I suspect Tristram might jump at the chance to put together some polls at some point. :)

You may be sure, Linda, that I will not readily forego an opportunity to start a poll. Maybe there will be one this or next week but I'll have to discuss things with Kim first.

You may be sure, Linda, that I will not readily forego an opportunity to start a poll. Maybe there will be one this or next week but I'll have to discuss things with Kim first.One good thing about our present reading speed is that you can soon catch up with us again ;-)

Great job, Tristram, with your summing up. As I got a late start to this I'm avoiding reading all of the comments which I don't like to do.

Great job, Tristram, with your summing up. As I got a late start to this I'm avoiding reading all of the comments which I don't like to do.I had read this quite some years ago. I cannot remember a thing so it's like a new book. On a first reading of these chapters I was at a loss to get what he was talking about. I had to reread once or twice before it clicked. I was pleasantly surprised. It will be interesting to watch the twists and turns of each character's life. I don't expect them to be straightforward ...

Thanks, Xan, for the reminder of the PF song. I had forgotten that it was a revolutionary song. Brilliant!

It's nice to have you aboard, Hilary! I can understand how you feel about re-reading HT as a new book because for me it is actually the same because my first reading of the book happened a long time ago. All I remembered was the Gradgrind and Bounderby characters as well as the description of Coketown, and the first scene, of course. As to the plot, I am tabula rasa, which is good since I cannot drop any spoilers.

It's nice to have you aboard, Hilary! I can understand how you feel about re-reading HT as a new book because for me it is actually the same because my first reading of the book happened a long time ago. All I remembered was the Gradgrind and Bounderby characters as well as the description of Coketown, and the first scene, of course. As to the plot, I am tabula rasa, which is good since I cannot drop any spoilers.So let's enjoy the read and see where Dickens will lead us.

Tristram wrote: "students are becoming less and less self-dependent and instead want to know more and more what they are supposed to answer.

Tristram wrote: "students are becoming less and less self-dependent and instead want to know more and more what they are supposed to answer. The Gradgrind way is not the only one to make young people stop thinking for themselves."

Here is a section of a speech by Dickens he gave in 1857 telling the listeners of the schools he "did not like".

SPEECH: LONDON, NOVEMBER 5, 1857.

Speech given by Charles Dickens at the fourth anniversary dinner of the Warehousemen and Clerks Schools

Thursday evening, Nov. 5th, 1857,

The London Tavern

On the subject which had brought the company together Mr. Dickens spoke as follows:

"I must now solicit your attention for a few minutes to the cause of your assembling together — the main and real object of this evening’s gathering; for I suppose we are all agreed that the motto of these tables is not “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die;” but, “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we live.” It is because a great and good work is to live to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to live a greater and better life with every succeeding to-morrow, that we eat and drink here at all. Conspicuous on the card of admission to this dinner is the word “Schools.” This set me thinking this morning what are the sorts of schools that I don’t like. I found them on consideration, to be rather numerous. I don’t like to begin with, and to begin as charity does at home — I don’t like the sort of school to which I once went myself — the respected proprietor of which was by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know; one of the worst-tempered men perhaps that ever lived, whose business it was to make as much out of us and put as little into us as possible, and who sold us at a figure which I remember we used to delight to estimate, as amounting to exactly 2 pounds 4s. 6d. per head. I don’t like that sort of school, because I don’t see what business the master had to be at the top of it instead of the bottom, and because I never could understand the wholesomeness of the moral preached by the abject appearance and degraded condition of the teachers who plainly said to us by their looks every day of their lives, “Boys, never be learned; whatever you are, above all things be warned from that in time by our sunken cheeks, by our poor pimply noses, by our meagre diet, by our acid-beer, and by our extraordinary suits of clothes, of which no human being can say whether they are snuff-coloured turned black, or black turned snuff-coloured, a point upon which we ourselves are perfectly unable to offer any ray of enlightenment, it is so very long since they were undarned and new.” I do not like that sort of school, because I have never yet lost my ancient suspicion touching that curious coincidence that the boy with four brothers to come always got the prizes. In fact, and short, I do not like that sort of school, which is a pernicious and abominable humbug, altogether. Again, ladies and gentlemen, I don’t like that sort of school — a ladies’ school — with which the other school used to dance on Wednesdays, where the young ladies, as I look back upon them now, seem to me always to have been in new stays and disgrace — the latter concerning a place of which I know nothing at this day, that bounds Timbuctoo on the north-east — and where memory always depicts the youthful enthraller of my first affection as for ever standing against a wall, in a curious machine of wood, which confined her innocent feet in the first dancing position, while those arms, which should have encircled my jacket, those precious arms, I say, were pinioned behind her by an instrument of torture called a backboard, fixed in the manner of a double direction post. Again, I don’t like that sort of school, of which we have a notable example in Kent, which was established ages ago by worthy scholars and good men long deceased, whose munificent endowments have been monstrously perverted from their original purpose, and which, in their distorted condition, are struggled for and fought over with the most indecent pertinacity. Again, I don’t like that sort of school — and I have seen a great many such in these latter times — where the bright childish imagination is utterly discouraged, and where those bright childish faces, which it is so very good for the wisest among us to remember in after life — when the world is too much with us, early and late 22 — are gloomily and grimly scared out of countenance; where I have never seen among the pupils, whether boys or girls, anything but little parrots and small calculating machines. Again, I don’t by any means like schools in leather breeches, and with mortified straw baskets for bonnets, which file along the streets in long melancholy rows under the escort of that surprising British monster — a beadle, whose system of instruction, I am afraid, too often presents that happy union of sound with sense, of which a very remarkable instance is given in a grave report of a trustworthy school inspector, to the effect that a boy in great repute at school for his learning, presented on his slate, as one of the ten commandments, the perplexing prohibition, “Thou shalt not commit doldrum.” Ladies and gentlemen, I confess, also, that I don’t like those schools, even though the instruction given in them be gratuitous, where those sweet little voices which ought to be heard speaking in very different accents, anathematise by rote any human being who does not hold what is taught there. Lastly, I do not like, and I did not like some years ago, cheap distant schools, where neglected children pine from year to year under an amount of neglect, want, and youthful misery far too sad even to be glanced at in this cheerful assembly."

With so much anguish at the English boarding school system (read Orwell's "Such, Such were the Joys," link below), it's amazing that it stuck around so long and so persistently.

With so much anguish at the English boarding school system (read Orwell's "Such, Such were the Joys," link below), it's amazing that it stuck around so long and so persistently. Link to Orwell's essay:

http://www.orwell.ru/library/essays/j...

Wikipedia article on the school (no longer in existence) he attended:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Cypr...

When he speaks of "bright childish imagination" and "bright childish faces", it once more shows how sensitive Dickens was to the needs of children and to the fact that childhood is a period in life that is to be protected - an idea that was probably not rooted in Victorian society as yet. I don't wonder why Dickens was so capable of making us feel pity with David Copperfield in the early chapters of the novel, or feel afraid for Pip at the beginning of HE - Dickens simply had the skill of seeing life through the eyes of a child sometimes.

When he speaks of "bright childish imagination" and "bright childish faces", it once more shows how sensitive Dickens was to the needs of children and to the fact that childhood is a period in life that is to be protected - an idea that was probably not rooted in Victorian society as yet. I don't wonder why Dickens was so capable of making us feel pity with David Copperfield in the early chapters of the novel, or feel afraid for Pip at the beginning of HE - Dickens simply had the skill of seeing life through the eyes of a child sometimes.

Tristram wrote: "When he speaks of "bright childish imagination" and "bright childish faces", it once more shows how sensitive Dickens was to the needs of children and to the fact that childhood is a period in life..."

Tristram wrote: "When he speaks of "bright childish imagination" and "bright childish faces", it once more shows how sensitive Dickens was to the needs of children and to the fact that childhood is a period in life..."To what extent do you think Dickens's eyes of perception where sharpened because of his own experience and memory. I know that question has been asked and discussed countless times, but it is, I believe, still one of the central questions to consider.

I believe Dickens held on to the remberences of his own poverty in childhood, both physical and emotional, and those two memories fuelled his entire writing career.

Peter, I would definitely agree with you that Dickens's own experience had a hand in his perception of social wrongs and in his writing about them. We saw that many details of his traumatic spell at Warren's Blacking Factory found their way into David Copperfield, as these were memories he would not divulge to anyone (maybe with the exception of Foster) but that still had to be given vent to. If I remember correctly, even Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey and Son is modelled on a landlady Dickens lived with when he was working in that factory.

Peter, I would definitely agree with you that Dickens's own experience had a hand in his perception of social wrongs and in his writing about them. We saw that many details of his traumatic spell at Warren's Blacking Factory found their way into David Copperfield, as these were memories he would not divulge to anyone (maybe with the exception of Foster) but that still had to be given vent to. If I remember correctly, even Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey and Son is modelled on a landlady Dickens lived with when he was working in that factory.I also seem to remember that Dickens was quite sore about the chances of education he had lost or been made to lose at that time, and maybe that is why he had such a keen eye for the "bright childish imagination" - his own was, at that time, prevented from developing freely.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when..."

For anyone interested in collecting Dickens works in a limited edition without breaking the bank:

http://nonesuchdickens.com/

Orginal plates used to make books, with original artwork!

I own these and absolutely love them.

shaymond wrote: "For anyone interested in collecting Dickens works in a limited edition without breaking the bank:"

shaymond wrote: "For anyone interested in collecting Dickens works in a limited edition without breaking the bank:"They sound wonderful, but Amazon prices a set of 6 for over $800. That would, regrettably, break the bank for me - my bank is very fragile these days!

Not that everyone will have this kind of luck, but my husband found an almost complete set of Dickens from 1885 at Goodwill for $2.62 each. Best gift I ever got! I've found lovely hardcovers in various editions at used book sales, yard sales, etc., too. I admit it - I'm a Dickens hoarder, but I'm also a cheapskate! :-)

Oh my. That is a lot. You can get them individually brand new for between 30 and 40 dollars each on amazon. Or even less used from 3rd party. Not to bad for a limited edition. They aren't leather and gold plated like Easton Press, but they are more than half the price.

Oh my. That is a lot. You can get them individually brand new for between 30 and 40 dollars each on amazon. Or even less used from 3rd party. Not to bad for a limited edition. They aren't leather and gold plated like Easton Press, but they are more than half the price. Can't beat your Goodwill price! That was an excellent gift.

Villa du Camp de Droite, Thursday, June 22nd, 1854.

Villa du Camp de Droite, Thursday, June 22nd, 1854.My dear Wills,

I have nothing to say, but having heard from you this morning, think I may as well report all well.

We have a most charming place here. It beats the former residence all to nothing. We have a beautiful garden, with all its fruits and flowers, and a field of our own, and a road of our own away to the Column, and everything that is airy and fresh. The great Beaucourt hovers about us like a guardian genius, and I imagine that no English person in a carriage could by any possibility find the place.

Of the wonderful inventions and contrivances with which a certain inimitable creature has made the most of it, I will say nothing, until you have an opportunity of inspecting the same. At present I will only observe that I have written exactly seventy-two words of "Hard Times," since I have been here.

The children arrived on Tuesday night, by London boat, in every stage and aspect of sea-sickness.

The camp is about a mile off, and huts are now building for (they say) sixty thousand soldiers. I don't imagine it to be near enough to bother us.

If the weather ever should be fine, it might do you good sometimes to come over with the proofs on a Saturday, when the tide serves well, before you and Mrs. W. make your annual visit. Recollect there is always a bed, and no sudden appearance will put us out.

Kind regards.

Ever faithfully.

C.D.

Kim wrote: "Villa du Camp de Droite, Thursday, June 22nd, 1854.

Kim wrote: "Villa du Camp de Droite, Thursday, June 22nd, 1854.My dear Wills,

I have nothing to say, but having heard from you this morning, think I may as well report all well.

We have a most charming pl..."

O.K. How grand it would have been to have Dickens invite us Pickwickians for a visit anytime we want where "no sudden appearance" would put him out.

Plus we would definitely not have outstayed our welcome like that "bony bore" Hans Christian Andersen ;-)

Plus we would definitely not have outstayed our welcome like that "bony bore" Hans Christian Andersen ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Plus we would definitely not have outstayed our welcome like that "bony bore" Hans Christian Andersen ;-)"

Tristram wrote: "Plus we would definitely not have outstayed our welcome like that "bony bore" Hans Christian Andersen ;-)"Oh! I'm so pleased to know that Dickens didn't like Andersen! I came across a book in my collection that a well-meaning person had given to my ill sister when she was in the hospital c. 1960 (she subsequently died, when I was a mere 1 year old). The book was a collection of stories by Andersen. Having seen the wonderful movie with Danny Kaye, I sat down with it, ready to be delighted. It was appalling! Awful, gruesome stories with no morality lessons to redeem them - a horrific gift for a child, in my mind. It's the only book I've ever thrown in the trash, even though it belonged to my sister. Danny Kaye and his script writers knew something about positive spin!

Yes, Mary Lou, Andersen's stories are often rather bleak and morbid. I have never liked his stories as a kid but preferred the Brothers Grimm or the fairy tales by Wilhelm Hauff. One Andersen tale I especially hated was "The Hardy Tin Soldier".

Yes, Mary Lou, Andersen's stories are often rather bleak and morbid. I have never liked his stories as a kid but preferred the Brothers Grimm or the fairy tales by Wilhelm Hauff. One Andersen tale I especially hated was "The Hardy Tin Soldier".

Tristram wrote: "Yes, Mary Lou, Andersen's stories are often rather bleak and morbid. I have never liked his stories as a kid but preferred the Brothers Grimm or the fairy tales by Wilhelm Hauff. One Andersen tale ..."

Tristram wrote: "Yes, Mary Lou, Andersen's stories are often rather bleak and morbid. I have never liked his stories as a kid but preferred the Brothers Grimm or the fairy tales by Wilhelm Hauff. One Andersen tale ..."Great. Now I have to go read that.

Tristram wrote: "One Andersen tale I especially hated was "The Hardy Tin Soldier".

Tristram wrote: "One Andersen tale I especially hated was "The Hardy Tin Soldier". Well that was odd. But Tristram, you just had to feel sorry for the tin soldier didn't you? After all, he only had one leg, and he fell out a window, and rode a paper boat through a sewer, and was chased by a rat, and was eaten by a fish and on and on and on........ And then there was a princess standing on one foot, and a cardboard castle, and a lake that was really a mirror, and........

poor, poor tin soldier.

Kim,

Kim,it is such a dreary story devoid of hope, and the ending is just terrible: "[...] and when the servant-maid took the ashes out next day, she found him in the shape of a little tin heart. But of the danser nothing remained but the little tinsel rose, and that was burned as black as coal."

The worst thing that befell the tin soldier was that he loved a woman with no heart. Hey, come on, that's no fairy tale stuff.

Everyman wrote: "And yet, education today, in this country at least, isn't all that far in principle from Gradgrind's principles. All this testing, testing, testing, is mostly testing for facts. Teachers are expected to cram into their students the facts they will need to pass these standardized tests..."

Everyman wrote: "And yet, education today, in this country at least, isn't all that far in principle from Gradgrind's principles. All this testing, testing, testing, is mostly testing for facts. Teachers are expected to cram into their students the facts they will need to pass these standardized tests..."This was my thought exactly. The policies begin by Michael Gove and continued by his Conservative party successors are right out of Mr. Gradgrind's Book of Facts. Ironically, the introduction to my edition by Dingle Foot (a great Dickensian name!), writing in 1955, comments upon how the educational attitudes of Hard Times were being replaced by a more progressive model and we wouldn't see their like again.

And it's good to have you back with us again.