Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

7/14-7/20: Fourth Day, Introduction & Stories 1-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:41AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

Boccaccio begins this day with a defense of his work as it is thus far completed. Although he says that portions of the earlier days were circulating among the literate citizens of Tuscany while the work was in progress, this is doubtful. Instead, Boccaccio is probably just shooting down potential detractors. Filostrato reigns during the fourth day, in which the storytellers tell tales of lovers whose relationship ends in disaster. This is the first day a male storyteller reigns.

So glad to see the group read still going strong. I've fallen behind (stuck in day II!) but I'll catch up... at some point. ^.^

So glad to see the group read still going strong. I've fallen behind (stuck in day II!) but I'll catch up... at some point. ^.^I'll post the illustrations later today. :)

Illustrations - Day IV Introduction

Illustrations - Day IV Introduction

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Filippo Balducci & son fils à Florence

Illustrations - Day IV Story 1

Illustrations - Day IV Story 1

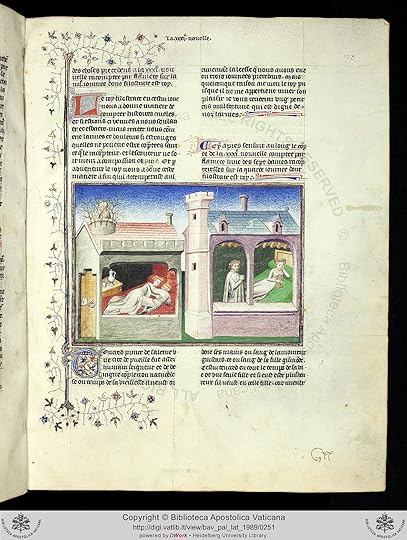

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Tancrède épiant les amants (Ghismonda et Guiscardo)

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

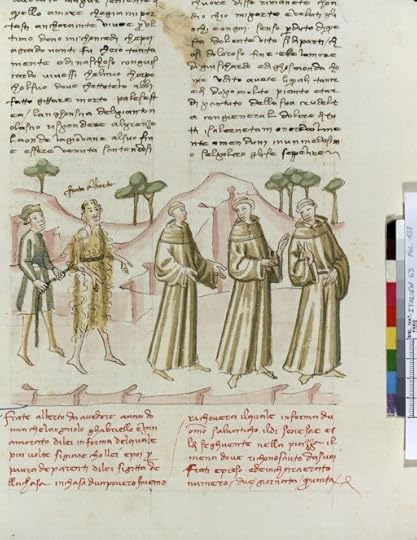

Illustrations - Day IV Story 2

Illustrations - Day IV Story 2

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Arrestation de Berto

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

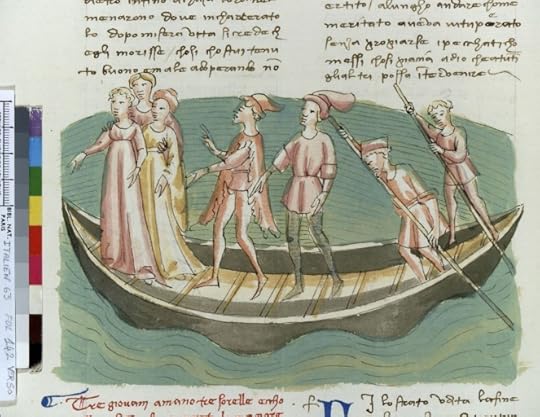

Illustrations - Day IV Story 3

Illustrations - Day IV Story 3

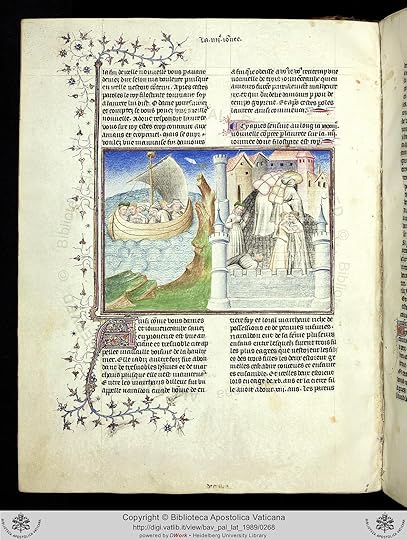

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Ninette et ses soeurs naviguant

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day IV Story 4

Illustrations - Day IV Story 4

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Mort de la Princesse de Tunis

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

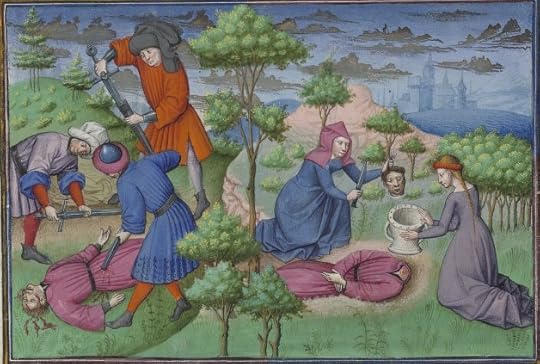

Illustrations - Day IV Story 5

Illustrations - Day IV Story 5

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Songe de Lisabetta. Lamentations de Lisabetta

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

{Judging by the subtitles of these illustrations, Day IV is on the tragic end!}

Book Portrait wrote: "So glad to see the group read still going strong. I've fallen behind (stuck in day II!) but I'll catch up... at some point. ^.^

I'll post the illustrations later today. :)"

Thank you BP. I was wondering what happened to you. I figured you were just busy over the summer. Hurry and catch up. It's no fun posting without you!

I'll post the illustrations later today. :)"

Thank you BP. I was wondering what happened to you. I figured you were just busy over the summer. Hurry and catch up. It's no fun posting without you!

The fourth day intro mentions "Envy's fiery and impetuous blast" and explains in the footnotes that Boccaccio borrowed this from Dante's Paradiso (xvii:133-4)

"The words you shout will be like blasts of wind

that strike the very summit of the trees."

Very religious symbolism here!

"The words you shout will be like blasts of wind

that strike the very summit of the trees."

Very religious symbolism here!

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Boccaccio begins this day with a defense of his work as it is thus far completed. Although he says that portions of the earlier days were circulating among the literate citizens of Tuscany while th..."

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Boccaccio begins this day with a defense of his work as it is thus far completed. Although he says that portions of the earlier days were circulating among the literate citizens of Tuscany while th..."I finally rejoined the group read. I just had to skip days II & III. <---- I iz a

I'd forgotten that Boccaccio sometimes addresses the reader and was lost for a moment... Interesting how he defends his work against (inexistant?) critics with visible faux modesty. Also interesting that he feels the need to justify his interest in women despite his grand old age (how old was he?!) but the little story of the young man raised away from society who first encounters women was priceless. :)

I enjoyed this week's stories with its blend of different genres, echoes of courtly love, fairy tales, pre-gothic gruesomeness, edifying tales, sensational faits divers... I kept thinking 'Ooh Shakespeare would have loved that!'

Toto wrote: "Dinner with spaghetti with pesto!"

Toto wrote: "Dinner with spaghetti with pesto!"*lol* That story was so tragically tragic. Here's another illustration of the famous pot of basil:

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6...

I am a bit behind. Will catch up the two remaining tales tomorrow and start with this week.

Thank you, BP for the illustrations.

Thank you, BP for the illustrations.

Book Portrait wrote: "finally rejoined the group read. I just had to skip days II & III. <---- I iz a brainy sneaky reader. ^.^

LOL BP, you beat us again! Like Kalli, I too need to catch up!

LOL BP, you beat us again! Like Kalli, I too need to catch up!

I enjoy when places are mentioned or real people... anchoring the story in reality.. it must have seemed so much more approachable.. The 4th story mentions King William II of Sicily.

He reigned from 1166 to 1189 and here he is offering the Monreale Cathedral to the Virgin.

He reigned from 1166 to 1189 and here he is offering the Monreale Cathedral to the Virgin.

Book Portrait wrote: "ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Boccaccio begins this day with a defense of his work as it is thus far completed. Although he says that portions of the earlier days were circulating among the literat..."

Yes, this addressing the reader is always very interesting... Dante did it also...

Yes, this addressing the reader is always very interesting... Dante did it also...

I found another of Isabella and the pot of basil as well as poem by Keats:

Isabella and the pot of basil, William Holman Hunt, 1867

John Keats (1795–1821). The Poetical Works of John Keats. 1884.

Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil

A Story from Boccaccio

I.

FAIR Isabel, poor simple Isabel!

Lorenzo, a young palmer in Love’s eye!

They could not in the self-same mansion dwell

Without some stir of heart, some malady;

They could not sit at meals but feel how well 5

It soothed each to be the other by;

They could not, sure, beneath the same roof sleep

But to each other dream, and nightly weep.

To read the entire poem: http://www.bartleby.com/126/38.html

Isabella and the pot of basil, William Holman Hunt, 1867

John Keats (1795–1821). The Poetical Works of John Keats. 1884.

Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil

A Story from Boccaccio

I.

FAIR Isabel, poor simple Isabel!

Lorenzo, a young palmer in Love’s eye!

They could not in the self-same mansion dwell

Without some stir of heart, some malady;

They could not sit at meals but feel how well 5

It soothed each to be the other by;

They could not, sure, beneath the same roof sleep

But to each other dream, and nightly weep.

To read the entire poem: http://www.bartleby.com/126/38.html

The Story of Lisabetta (IV.5)

On the fourth day, in which Filostrato decrees the narration of love stories with unhappy endings, Filomena recounts the story of Lisabetta and her lover Lorenzo, who is killed by the young girl's brothers after their love affair is discovered. Indeed, the most macabre of the ten stories told in this day, Filomena's narrative contains more details of mutilation (the cutting off of Lorenzo's head by Lisabetta for example) and of decomposition than any other novella of Boccaccio's Decameron. The emphasis on Lorenzo's decomposition and decay, mentioned three times, recalls elements of the plague as described by Boccaccio in the introduction. Although no direct mention of the plague appears after the author's lengthy portrayal at the beginning of the work, echoes of the epidemic are present in the novella of Lisabetta and Lorenzo.

Boccaccio explains that, in addition to the population losses from the pestilence inside the city of Florence, the surrounding countryside was affected as well by the plague's destruction. The group escapes from death's catastrophic effects in the urban center to the comfort of their country estates, even as Pampinea recognizes that the workers in the fields are dying along with their urban counterparts. On the first day, Pampinea strictly orders the servants who leave the company to perform household errands to avoid bringing displeasing news back to the brigata. The plague, and therefore death in general, is the unpleasant news which the group would like to ignore. Therefore, the presence of death on the fourth day could be construed as a reminder to the brigata of possible contamination and death.

Various elements of the introduction can be compared with points of Filomena's narrative. In the introduction, Boccaccio describes the Florentines fleeing the city, carrying flowers around with them to mask the stench of corpses and illness, fearing contamination from the decomposing bodies, and burying plague victims in mass graves. Lisabetta's brothers are merchants who left Tuscany, possibly San Gimignano or even Florence, to travel to Sicily. Lorenzo also left Pisa to travel with them. Messina can be taken as a metaphor for Florence and love as a metaphor for the plague. Discovered in the act of love by Lisabetta's brother, Lorenzo is taken outside the city, killed, and buried in an unmarked grave. This scene gains deeper meaning when compared to the portrayal of events in the Proem: "non bastando la terra sacra alle sepolture... si facevano per gli cimiterii delle chiese, poi che ogni parte era piena, fosse grandissime nelle quali a centinaia si mettevano i sopravegnenti... con poca terra si ricoprieno." Of course Lorenzo's grave is hidden with new dirt and leaves to hide the murder, but anonymous burial in the ground recalls aspects of the plague.

Lorenzo visits Lisabetta in a dream with torn and rotting clothes, alluding to his decomposition, and tells his lover where to locate his body. Lisabetta finds Lorenzo's body, cuts off his head, wraps it in a beautiful cloth, and gives it a loving burial. She plants basil in the pot over Lorenzo's head, an act which calls to mind the Florentines attempts to lessen the fetor of the plague's victims: "portando nelle mani chi fiori, chi erbe odorifere e chi diverse maniere di spezierie... estimando essere ottima cosa il cerebro con cotali odori confortare, con ciò fosse cosa che l'aere tutto paresse dal puzzo de' morti corpi e delle infermità e delle medicine compreso e puzzolente." When they leave Messina after disposing of Lorenzo's head, Lisabetta and her brothers go to Naples ("niuna altra medicina essere contro alle pistilenze migliore né così buona come il fuggir loro davanti") fearing that the murder might be discovered or possibly "mossi non meno da tema che la corruzione de' morti non gli offendesse." Lisabetta's brothers want to get rid of her lover without dishonor in the same way that the women of the brigata desire to leave Florence with honor - the same reason Filomena herself gives Pampinea in the Proem for inviting men to accompany them. As opposed to the Florentines who showed little love for their dead and dying during the plague, Lisabetta instead demonstrated an unabated affection for her lover in caring for Lorenzo's remains, however gruesome. Albeit the account of the plague and Filomena's story differ in many ways, similar plague-referential conditions are found in both.

On the fourth day, in which Filostrato decrees the narration of love stories with unhappy endings, Filomena recounts the story of Lisabetta and her lover Lorenzo, who is killed by the young girl's brothers after their love affair is discovered. Indeed, the most macabre of the ten stories told in this day, Filomena's narrative contains more details of mutilation (the cutting off of Lorenzo's head by Lisabetta for example) and of decomposition than any other novella of Boccaccio's Decameron. The emphasis on Lorenzo's decomposition and decay, mentioned three times, recalls elements of the plague as described by Boccaccio in the introduction. Although no direct mention of the plague appears after the author's lengthy portrayal at the beginning of the work, echoes of the epidemic are present in the novella of Lisabetta and Lorenzo.

Boccaccio explains that, in addition to the population losses from the pestilence inside the city of Florence, the surrounding countryside was affected as well by the plague's destruction. The group escapes from death's catastrophic effects in the urban center to the comfort of their country estates, even as Pampinea recognizes that the workers in the fields are dying along with their urban counterparts. On the first day, Pampinea strictly orders the servants who leave the company to perform household errands to avoid bringing displeasing news back to the brigata. The plague, and therefore death in general, is the unpleasant news which the group would like to ignore. Therefore, the presence of death on the fourth day could be construed as a reminder to the brigata of possible contamination and death.

Various elements of the introduction can be compared with points of Filomena's narrative. In the introduction, Boccaccio describes the Florentines fleeing the city, carrying flowers around with them to mask the stench of corpses and illness, fearing contamination from the decomposing bodies, and burying plague victims in mass graves. Lisabetta's brothers are merchants who left Tuscany, possibly San Gimignano or even Florence, to travel to Sicily. Lorenzo also left Pisa to travel with them. Messina can be taken as a metaphor for Florence and love as a metaphor for the plague. Discovered in the act of love by Lisabetta's brother, Lorenzo is taken outside the city, killed, and buried in an unmarked grave. This scene gains deeper meaning when compared to the portrayal of events in the Proem: "non bastando la terra sacra alle sepolture... si facevano per gli cimiterii delle chiese, poi che ogni parte era piena, fosse grandissime nelle quali a centinaia si mettevano i sopravegnenti... con poca terra si ricoprieno." Of course Lorenzo's grave is hidden with new dirt and leaves to hide the murder, but anonymous burial in the ground recalls aspects of the plague.

Lorenzo visits Lisabetta in a dream with torn and rotting clothes, alluding to his decomposition, and tells his lover where to locate his body. Lisabetta finds Lorenzo's body, cuts off his head, wraps it in a beautiful cloth, and gives it a loving burial. She plants basil in the pot over Lorenzo's head, an act which calls to mind the Florentines attempts to lessen the fetor of the plague's victims: "portando nelle mani chi fiori, chi erbe odorifere e chi diverse maniere di spezierie... estimando essere ottima cosa il cerebro con cotali odori confortare, con ciò fosse cosa che l'aere tutto paresse dal puzzo de' morti corpi e delle infermità e delle medicine compreso e puzzolente." When they leave Messina after disposing of Lorenzo's head, Lisabetta and her brothers go to Naples ("niuna altra medicina essere contro alle pistilenze migliore né così buona come il fuggir loro davanti") fearing that the murder might be discovered or possibly "mossi non meno da tema che la corruzione de' morti non gli offendesse." Lisabetta's brothers want to get rid of her lover without dishonor in the same way that the women of the brigata desire to leave Florence with honor - the same reason Filomena herself gives Pampinea in the Proem for inviting men to accompany them. As opposed to the Florentines who showed little love for their dead and dying during the plague, Lisabetta instead demonstrated an unabated affection for her lover in caring for Lorenzo's remains, however gruesome. Albeit the account of the plague and Filomena's story differ in many ways, similar plague-referential conditions are found in both.

Isabella by John Everett Millais

New light is being shed on a star painting in Tate Britain's new pre-Raphaelite exhibition after phallic symbols were apparently discovered in the work.

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde traces the 19th century British art movement led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

Tate curator Dr Carol Jacobi is challenging the reputation of Victorians being repressed with a research paper on the painting Isabella (1848) by Millais in the show.

Her paper, to be published through the Tate, examines phallic symbols in the painting of two merchant brothers from Florence who discover that their sister has been having an affair with a clerk, Lorenzo. In the medieval story, retold in the Keats poem Isabella, the enraged brothers murder the clerk but Isabella digs up his body and plants his head in a pot of basil.

Dr Jacobi said that the shadow of a nutcracker, as well as the shape of one of the brother's legs, appears to be phallic symbols.

''It's not a one-off or a Freudian slip. It enriches our understanding of what is so hard to do in painting. It enriches our understanding of the characters,'' she said.

''This exhibition gives us the chance to look at it. Is it deliberate? If so, why would he have included it? It's quite shocking and unusual. It might be that the brothers are thinking about the desire and the dangers of desire.

''But more research needs to be done into how the Victorians saw what was Millais' first pre-Raphaelite painting.''

Asked why the apparently phallic symbols were not noticed before, Dr Jacobi, whose paper is entitled Sugar, Salt And Curdled Milk: Millais And The Synthetic Subject, said: ''When you look at a painting you have a story in your mind, so if something slips out you don't see it.''

Dr Jacobi, who did not curate the Tate show, said another image in the painting, of salt being spilled, would have been familiar to Victorian audiences as a reference to a lack of sexual self-control.

New light is being shed on a star painting in Tate Britain's new pre-Raphaelite exhibition after phallic symbols were apparently discovered in the work.

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde traces the 19th century British art movement led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

Tate curator Dr Carol Jacobi is challenging the reputation of Victorians being repressed with a research paper on the painting Isabella (1848) by Millais in the show.

Her paper, to be published through the Tate, examines phallic symbols in the painting of two merchant brothers from Florence who discover that their sister has been having an affair with a clerk, Lorenzo. In the medieval story, retold in the Keats poem Isabella, the enraged brothers murder the clerk but Isabella digs up his body and plants his head in a pot of basil.

Dr Jacobi said that the shadow of a nutcracker, as well as the shape of one of the brother's legs, appears to be phallic symbols.

''It's not a one-off or a Freudian slip. It enriches our understanding of what is so hard to do in painting. It enriches our understanding of the characters,'' she said.

''This exhibition gives us the chance to look at it. Is it deliberate? If so, why would he have included it? It's quite shocking and unusual. It might be that the brothers are thinking about the desire and the dangers of desire.

''But more research needs to be done into how the Victorians saw what was Millais' first pre-Raphaelite painting.''

Asked why the apparently phallic symbols were not noticed before, Dr Jacobi, whose paper is entitled Sugar, Salt And Curdled Milk: Millais And The Synthetic Subject, said: ''When you look at a painting you have a story in your mind, so if something slips out you don't see it.''

Dr Jacobi, who did not curate the Tate show, said another image in the painting, of salt being spilled, would have been familiar to Victorian audiences as a reference to a lack of sexual self-control.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "I found another of Isabella and the pot of basil as well as poem by Keats:"

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "I found another of Isabella and the pot of basil as well as poem by Keats:"Wonderful! The Pre-Raphaelites really were into classics of late middle ages Italian literature! I wonder how much their passion spurred a renewed interest in Dante & Boccaccio (Keats wrote his poem after Hunt did his painting...) or whether these works were always popular... Italy probably always was a magnet for artists, painters and writers alike...

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "The Story of Lisabetta (IV.5)

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "The Story of Lisabetta (IV.5)On the fourth day, in which Filostrato decrees the narration of love stories with unhappy endings, Filomena recounts the story of Lisabetta and her lover Lorenzo, who..."

That's very interesting. Where did you find this analysis? I should have made the connection between the theme of death in this fourth day and the Plague but I mostly read these stories as emphaszing the power of love (and the strength of virtue as in the first story).

The plague, and therefore death in general, is the unpleasant news which the group would like to ignore.

The Brigata is actually succeeding in making me completely forget that there is the Black Plague in the background. Their courtly arrangement seems mostly geared toward entertainement...

Found more illustrations for story 1 (Ghismonda & Guiscardo's heart in a cup):

Found more illustrations for story 1 (Ghismonda & Guiscardo's heart in a cup):

by Bernardino Mei (1612-1676), Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena

Big: http://www.spsae-si.beniculturali.it/...

by William Hogarth, 1759

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/h...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigismun...

More illustrations: http://frankzumbach.wordpress.com/201...

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "I found another of Isabella and the pot of basil as well as poem by Keats:

Isabella and the pot of basil, William Holman Hunt, 1867

John Keats (1795–1821). The Poetical Works of John Keats...."

Reem, the image has disappeared...

Isabella and the pot of basil, William Holman Hunt, 1867

John Keats (1795–1821). The Poetical Works of John Keats...."

Reem, the image has disappeared...

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Isabella by John Everett Millais

New light is being shed on a star painting in Tate Britain's new pre-Raphaelite exhibition after phallic symbols were apparently discovered in the work.

Pre..."

Thank you for this, Reem... This is a spectacular painting, and I had forgotten about it when reading the story... When I contemplated the painting last I had not read Boccaccio yet...

New light is being shed on a star painting in Tate Britain's new pre-Raphaelite exhibition after phallic symbols were apparently discovered in the work.

Pre..."

Thank you for this, Reem... This is a spectacular painting, and I had forgotten about it when reading the story... When I contemplated the painting last I had not read Boccaccio yet...

Book Portrait wrote: "Found more illustrations for story 1 (Ghismonda & Guiscardo's heart in a cup):

by Bernardino Mei (1612-1676), Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena

Big: http://www.spsae-si.beniculturali.it/......"

The one by Mei...!!!!!!

by Bernardino Mei (1612-1676), Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena

Big: http://www.spsae-si.beniculturali.it/......"

The one by Mei...!!!!!!

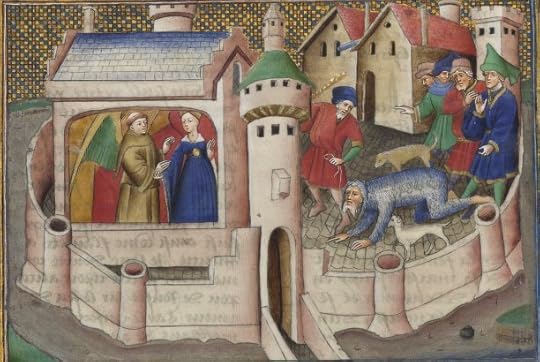

One more illustration of poor Ghismonda:

One more illustration of poor Ghismonda:

Big: http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterEl...

or as B& W microfiche: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Guiscardo rejoignant Ghismonda ; assassinat de Guiscardo ; Ghismonda recevant le coeur de Guiscardo

BnF ms 240

Toto wrote: "I like the illustrations, Book Portrait, thanks. Story IV's illustration cracked me up: ladies place the severed head in the pot so calmly. Soon, they'll put some soil over it and plant the basil ..."

Toto wrote: "I like the illustrations, Book Portrait, thanks. Story IV's illustration cracked me up: ladies place the severed head in the pot so calmly. Soon, they'll put some soil over it and plant the basil ..."Yes, I read that part on my Kindle at night and highlighted....Venice did not fare well in that story!