The Pickwick Club discussion

Sketches by Boz

>

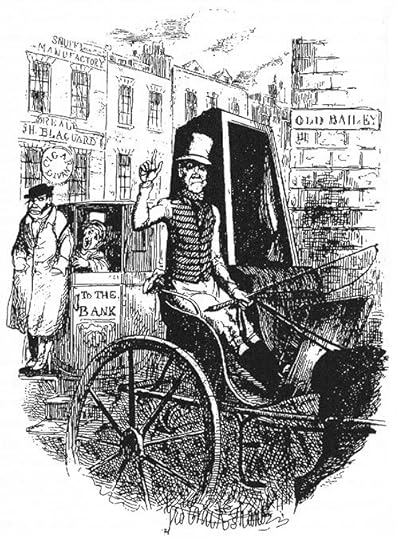

Scenes, 17: The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is a shortened version of cabriolet. Dickens may have ridden in a hackney coach; today a cab driver is sometimes referred to as a hack. Then, the drivers, whose behavior was often less than ethical, were called cads. A cad is no longer a profession, but someone whose behavior is still unethical. And, of course, omnibus seems to have been shortened over time to bus. Today's meanings may have different etymologies that I'm not aware of, but these make sense to me.

Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is a shortened version of cabriolet. Dickens may have ridden in a hackney coach; today a cab driver is sometimes referred to as a hack. Then, the drivers, whose behavior was often less than ethical, were called cads. A cad is no longer a profession, but someone whose behavior is still unethical. And, of course, omnibus seems to have been shortened over time to bus. Today's meanings may have different etymologies that I'm not aware of, but these make sense to me. Can anyone tell me what is meant by "pull up" in the following passage? Obviously not a good thing, but I couldn't make it out with any precision based on the context:

The dispute had attained a pretty considerable

height, when at last the loquacious little gentleman, making a

mental calculation of the distance, and finding that he had already

paid more than he ought, avowed his unalterable determination to

'pull up' the cabman in the morning.

'Now, just mark this, young man,' said the little gentleman, 'I'll

pull you up to-morrow morning.'

Mary Lou wrote: "Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is..."I don't know what "pull up" means either but I agree with you that it does not seem to be a compliment or anything one should look forward to. Just a guess.

It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight into writing novels.

It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight into writing novels.

Peter wrote: "It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight into writing novels."

Peter wrote: "It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight into writing novels."More bird imagery!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight int..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "It's hard for me not to imagine the sketches as Dickens, as a very young writer, standing on the edge of a nest, flapping his literary wings and getting ready for his first flight int..."Miss Flite made me do it. :-))

I have read that young ladies actually took lessons in how to enter and exit a vehicle. I find some of the sketches are like a microscope that zooms in on an idea, person, item or action. If we were to be magically transported back to Victorian times we could learn more about day-to-day activity by reading the sketches than a novel.

Kim wrote: "But Dickens could write about anything."

Kim wrote: "But Dickens could write about anything."I had the same thought when starting with the Sketches, Kim. My first apprehension was that reading them would be somewhat boring because after all, they are often not very narrative, and I like stories. But Dickens's sense of humour, his keen observation and his sense for the absurd have made most of those Sketches a treat for me. Even if I don't understand every Victorian detail.

Mary Lou wrote: "Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Transportation, at least as a topic to read about, isn't really something that interests me, so the thing that struck me most in this sketch was the evolution of the English language. Cab surely is..."These are interesting points for me as a non-native speaker, Mary Lou! I was also quite puzzled at how many different types of coaches there were, and maybe that would be another idea for a list: Different coaches in Dickens's novels.

Shall I start another list? I could title it "Round, round, I get around" after The famous Beach Boy tune.

Shall I start another list? I could title it "Round, round, I get around" after The famous Beach Boy tune.

Here's a start for you Peter. I think I'll skip traveling in any of them, now a sleigh would be another thing. :-) I wonder how you get on that bicycle type of thing in the first row?

Here's a start for you Peter. I think I'll skip traveling in any of them, now a sleigh would be another thing. :-) I wonder how you get on that bicycle type of thing in the first row?

Peter wrote: "I have read that young ladies actually took lessons in how to enter and exit a vehicle."

Peter wrote: "I have read that young ladies actually took lessons in how to enter and exit a vehicle."Thinking of ladies taking lessons got me interested in looking up the lessons and although I've yet to find a lesson on how to get into a carriage, I have found some other rather unusual lessons, unusual to me anyway:

"How wives should speak to her husband"

"How a lady should speak of her husband.--A lady should not say "my husband," except among intimates; in every other case she should address him by his name, calling him "Mr." It is equally proper, except on occasions of ceremony, and while she is quite young, to designate him by his christian name.

Never use the initial of a person's name to designate him; as "Mr. P.," "Mr. L.," etc. Nothing is so odious as to hear a lady speak of her husband, or, indeed, any one else, as "Mr. B."

How a lady should be spoken of by her husband.--It is equally improper for a gentleman to say "my wife," except among very intimate friends; he should mention her as "Mrs. So-and-so." When in private, the expression "my dear," or merely the christian name, is considered in accordance with the best usage among the more refined.

Speaking of one's self.--When we speak of ourself and another person, whether he is absent or present, propriety requires us to mention ourselves last. Thus we should say, he and I, you and I."

"Undue pretensions to learning."

"Avoid even the appearance of pedantry. If you are conversing with persons of very limited attainments, you will make yourself far more acceptable, as well as useful to them, by accommodating yourself to their capacities, than by compelling them to listen to what they cannot understand. Possibly in some instances you may make them stare at your supposed wisdom, and perhaps they may even quote you as an oracle of learning; but it is much more probable that even they will smile at such an exhibition as a contemptible weakness.

With the intelligent and discerning, this effect will certainly be produced; and that whether your pretensions to learning are well founded or not; the simple fact that you aim to appear learned, that you deal much in allusion to the classics, or the various departments of science, with an evident intention to display your familiarity with them, will be more intolerable than absolute ignorance."

"Gait and carriage."

"A lady ought to adopt a modest and measured gait; too great hurry injures the grace which ought to characterize her. She should not turn her head on one side and on the other, especially in large towns or cities, where this bad habit seems to be an invitation to the impertinent. A lady should not present herself alone in a library, or a museum, unless she goes there to study, or work as an artist."

"Raising the dress."

"When tripping over the pavement, a lady should gracefully raise her dress a little above her ankle. With the right hand, she should hold together the folds of her gown, and draw them towards the right side. To raise the dress on. both sides, and with both hands, is vulgar. This ungraceful practice can only be tolerated for a moment, when the mud is very deep."

And to think that in the 21C people simply say "Yo," "hey you" and "waz up."

And to think that in the 21C people simply say "Yo," "hey you" and "waz up."Of course, in Canada, you would add "eh" after most comments. :-))

Kim wrote: "Thinking of ladies taking lessons got me interested in looking up the lessons and although I'..."

Kim wrote: "Thinking of ladies taking lessons got me interested in looking up the lessons and although I'..."An acquaintance of mine could benefit from the advice on pretensions. She can ruin any pleasant conversation by throwing in obscure Shakespeare quotes or references to Robespierre.

You brought back a pleasant memory of my Dad who died earlier this year. As long as I can remember, he referred to my mother as "Mrs. P----" when he was talking to others, and often when addressing her in front of others. I guess because of that and the fact that I read a lot of 19th century novels, it seemed perfectly normal. But now that both my parents are gone and I haven't heard it in a long time, you made me realize how odd that is by current standards. Thinking about it brought a smile to my face, though, so thank you for stirring up that memory. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Thinking about it brought a smile to my face, though, so thank you for stirring up that memory. :-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "Thinking about it brought a smile to my face, though, so thank you for stirring up that memory. :-)"Oh, you're very welcome! I often think of my Dad, he died four years ago, with a smile on my face, he was quite the odd character! I often think of the silly things he would tell us, such as "never let the preacher pray for you, especially in church, once the preacher gets a hold on your name he'll pray you to death." He claimed everyone the pastor prays for in church dies, I guess we'd live forever if it wasn't for that. :-)

to pull someone up

to pull someone upNot knowing the meaning of that expression was like wormwood to me, and finally I had the idea of looking it up in Partridge's Dictionary of Historical Slang, and there I found this:

"*pull up. To arrest: 1812, Vaux: c. >, by 1835, low s. >, by 1870, coll > by 1910, S.E. Dickens in Boz. Ex the act of pulling up, of checking, a fugitive, cf. PULL, v., 1."

S.E. is short here for "standard English", and "c." stands for "cant, language of the underworld".

Having that book handy, I also looked up "spinach" and found

"spinach (occ. spelt spin(n)age, gammon and. Nonsense; HUMBUG: coll: 1850, Dickens, 'What a world of gammon and spinnage it is, though, ain't it!'; ob. The words gammon and spinage are part of the refrain to the song, 'A frog he would a-wooing go'. (Early C.19) cf. GAMMON"

"ob." stands for "obsolescent" in Partridge.

Then I looked what major work Dickens had finished in 1850, and seeing it was DC, I had a look at Gutenberg and found that the quotation given by Partridge is from Chapter 22 of DC and is used by Miss Mowcher.

And now I'm really hungry and happen to have some spinach in the fridge ;-)

Kim wrote: ""never let the preacher pray for you, especially in church, once the preacher gets a hold on your name he'll pray you to death." "

Kim wrote: ""never let the preacher pray for you, especially in church, once the preacher gets a hold on your name he'll pray you to death." "That is a really nice quotation, Kim!

Tristram wrote: "And now I'm really hungry and happen to have some spinach in the fridge ;-)"

Tristram wrote: "And now I'm really hungry and happen to have some spinach in the fridge ;-)" Ah, you can eat that with your eel, smoked, canned, whatever it is. I didn't know you could eat an eel. :-)

By the way, why would a frog go a-wooing?

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "And now I'm really hungry and happen to have some spinach in the fridge ;-)"

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "And now I'm really hungry and happen to have some spinach in the fridge ;-)" Ah, you can eat that with your eel, smoked, canned, whatever it is. I didn't know you could eat an ee..."

I imagine a frog would go "a-wooing" in order to get a lady friend back to his (lily) pad.

That reminds me, I wanted to look that up.......

That reminds me, I wanted to look that up.......AAH!! There are actually two different versions of this:

A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go (Version 1)

" A frog he would a-wooing go, mm mm, mm mm,

A frog he would a-wooing go,

Whether his mother would let him or no, mm mm, mm mm.

He rode right to Miss Mousie's den, mm mm, mm mm,

He rode right to Miss Mousie's den,

Said he, "Miss Mousie are you within?" mm mm, mm mm.

Oh yes, Sir Frog, I sit and spin, mm mm, mm mm,

Oh yes, Sir Frog, I sit and spin,

So open the door and walk right in, mm mm, mm mm.

He said, "Miss Mousie I've come to see," mm mm, mm mm,

He said, "Miss Mousie I've come to see,

If you, Miss Mousie, will marry me?" mm mm, mm mm.

I don't know what to say to that, mm mm, mm mm,

I don't know what to say to that,

'Til I can see my Uncle Rat, mm mm, mm mm.

When Uncle Rat came riding home, mm mm, mm mm,

When Uncle Rat came riding home,

Said he, "Whose been here since I've been gone?" mm mm, mm mm.

A fine young gentleman has been here, mm mm, mm mm,

A fine young gentleman has been here,

Who wants to marry me, that is clear, mm mm, mm mm.

So Uncle Rat, he rode to town, mm mm, mm mm,

So Uncle Rat, he rode to town,

And bought his niece a wedding gown, mm mm, mm mm.

Where shall our wedding supper be, mm mm, mm mm,

Where shall our wedding supper be?

Down in the trunk of the hollow tree, mm mm, mm mm.

The first to come was the Bumble Bee, mm mm, mm mm,

The first to come was the Bumble Bee,

He strung his fiddle over his knee, mm mm, mm mm.

The next to come was a Crawley Bug, mm mm, mm mm,

The next to come was a Crawley bug,

He broke the bottle and smashed the jug, mm mm, mm mm.

The next to come was the Captain Flea, mm mm, mm mm,

The next to come was the Captain Flea,

He danced a jig with the Bumble Bee, mm mm, mm mm.

The Frog and Mouse, they went to France, mm mm, mm mm,

The Frog and Mouse, they went to France,

And this is the end of my romance, mm mm, mm mm."

A Frog he would a-wooing go (version 2)

" A variation of Frog Went A-Courting. It is not known who Anthony Rowley was. The purpose seems to be to satirize the rural gentry of Suffolk: Rowley, Poley, Bacon and Green were four families of Suffolk notables.

Lyrics

A Frog he would a wooing go, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

A Frog he would a-wooing go, Whether his mother would let him or no,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

He saddled and bridled a great black snail, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

He saddled and bridled a great black snail, And rode between the horns and the tail,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

So off he set with his opera hat, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

So off he set with his opera hat, And on the way he met with a rat,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

They rode till they came to Mousey Hall, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

They rode till they came to Mousey Hall, And there they both did knock and call,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

"Pray, Mrs. Mouse, are you within?" Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

"Pray, Mrs. Mouse, are you within?" "Oh yes, sir, here I sit and spin."

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

Then Mrs. Mouse she did come down, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

Then Mrs. Mouse she did come down, All smartly dressed in a russet gown,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

"Pray, Mrs. Mouse, can you give us some beer," Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

"Pray, Mrs. Mouse, can you give us some beer, That froggy and I may have good cheer?"

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

She had not been sitting long to spin, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

She had not been sitting long to spin, When the cat and the kittens came tumbling in,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

The cat she seized Master Rat by the crown, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

The cat she seized Master Rat by the crown, The kitten she pulled Miss Mousey down,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

This put Mr. Frog in a terrible fright, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

This put Mr. Frog in a terrible fright, He took up his hat and he wished them "Good night!"

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

And as he was passing over the brook, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

And as he was passing over the brook, A lily white duck came and gobbled him up,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley.

So there's an end of one, two, and three, Heigh-ho, says Rowley,

So there's an end of one, two, and three, The Rat, the Mouse, and little Froggy,

With a Roley, Poley, Gammon and Spinach, Heigh-ho says Anthony Rowley."

Rats, mice, crawly bugs, fleas, snails, this song couldn't get much worse.

Kim wrote: "Rats, mice, crawly bugs, fleas, snails, this song couldn't get much worse."

Kim wrote: "Rats, mice, crawly bugs, fleas, snails, this song couldn't get much worse."You are right. Add flies and spiders and panda bears and you would have a collection of the most disagreeable animals ever.

By the way, Kim, don't tell me people do not eat eel in Pennsylvania. It is a very delicious fish.

"He was a man of most simple and prepossessing appearance. He was a brown-whiskered, white-hatted, no-coated cabman; his nose was generally red, and his bright blue eye not unfrequently stood out in bold relief against a black border of artificial workmanship; his boots were of the Wellington form, pulled up to meet his corduroy knee-smalls, or at least to approach as near them as their dimensions would admit of; and his neck was usually garnished with a bright yellow handkerchief. In summer he carried in his mouth a flower; in winter, a straw—slight, but, to a contemplative mind, certain indications of a love of nature, and a taste for botany."

Dickens tells us this man drives a gorgeously painted, bright red cab that can be seen everywhere you go:

"there was the red cab, bumping up against the posts at the street corners, and turning in and out, among hackney-coaches, and drays, and carts, and waggons, and omnibuses, and contriving by some strange means or other, to get out of places which no other vehicle but the red cab could ever by any possibility have contrived to get into at all."

Dickens then describes getting in and out of cabs in such a way that makes me extremely glad I have to do neither one:

"Some people object to the exertion of getting into cabs, and others object to the difficulty of getting out of them; we think both these are objections which take their rise in perverse and ill-conditioned minds. The getting into a cab is a very pretty and graceful process, which, when well performed, is essentially melodramatic........ You single out a particular cab, and dart swiftly towards it. One bound, and you are on the first step; turn your body lightly round to the right, and you are on the second; bend gracefully beneath the reins, working round to the left at the same time, and you are in the cab. There is no difficulty in finding a seat: the apron knocks you comfortably into it at once, and off you go."

"The getting out of a cab is, perhaps, rather more complicated in its theory, and a shade more difficult in its execution. We have studied the subject a great deal, and we think the best way is, to throw yourself out, and trust to chance for alighting on your feet. If you make the driver alight first, and then throw yourself upon him, you will find that he breaks your fall materially. In the event of your contemplating an offer of eightpence, on no account make the tender, or show the money, until you are safely on the pavement. It is very bad policy attempting to save the fourpence. You are very much in the power of a cabman, and he considers it a kind of fee not to do you any wilful damage. Any instruction, however, in the art of getting out of a cab, is wholly unnecessary if you are going any distance, because the probability is, that you will be shot lightly out before you have completed the third mile."

This whole thing, other than making me glad I never have to ride in a cab, makes me wonder how in the world Dickens thought of these things to write about. I have never in my life had any urge to write down any experience I have had getting in or out of one of our cars. Or anyone else's car for that matter. But Dickens could write about anything.

When we move on from the red cab driver we come to Mr. William Barker. Dickens says:

"Mr. William Barker, then, for that was the gentleman’s name, Mr. William Barker was born—but why need we relate where Mr. William Barker was born, or when? Why scrutinise the entries in parochial ledgers, or seek to penetrate the Lucinian mysteries of lying-in hospitals? Mr. William Barker was born, or he had never been. There is a son—there was a father. There is an effect—there was a cause. Surely this is sufficient information for the most Fatima-like curiosity; and, if it be not, we regret our inability to supply any further evidence on the point. Can there be a more satisfactory, or more strictly parliamentary course? Impossible."

We are told that Mr. Barker in his younger days had a weakness, it was love. He loved ladies, liquids, and pocket-hankerchiefs, and this love extended itself to other people's properties.

"There is something very affecting in this. It is still more affecting to know, that such philanthropy is but imperfectly rewarded. Bow-street, Newgate, and Millbank, are a poor return for general benevolence, evincing itself in an irrepressible love for all created objects. Mr. Barker felt it so. After a lengthened interview with the highest legal authorities, he quitted his ungrateful country, with the consent, and at the expense, of its Government; proceeded to a distant shore; and there employed himself, like another Cincinnatus, in clearing and cultivating the soil—a peaceful pursuit, in which a term of seven years glided almost imperceptibly away."

Mr. Barker, once he returns from his seven years on a distant shore, becomes a cad on an omnibus, and as Dickens says:

"To recapitulate all the improvements introduced by this extraordinary man into the omnibus system—gradually, indeed, but surely—would occupy a far greater space than we are enabled to devote to this imperfect memoir."

I will leave the rest for you to read and I believe I have an illustration for this chapter. I'll go get it.