Bright Young Things discussion

This topic is about

Every Man Dies Alone

Group Reads Archive

>

April 2014 - Every Man Dies Alone by Hans Fallada

I've found some great discussion questions for this book on the Penguin website: http://www.penguin.com.au/products/97...

1. What is your reaction to the portrayal of the Quangels' marriage in the novel? Did your view of their relationship change during the course of the story?

2. The idea of resistance is key to Alone in Berlin. How successful do you feel the Quangels' act of resistance to the Nazi regime is? Did they ultimately achieve anything?

3. The novel opens by describing the residents of a house on Jablonski Street. What kind of atmosphere did you think this description creates? How does the novelist portray life in wartime Berlin?

4. At one point in the novel Otto Quangel states that 'No one could believe in God any more'. What is your view of this statement? Do you think Alone in Berlin portrays a godless world? Is it possible to retain a sense of faith when you are surrounded by cruelty?

5. What is your reaction to the character of the Gestapo Inspector Escherich? Did you have any sympathy for his predicament? Do you think it is possible to sympathize with an 'evil' character?

6. The novel's German title translates directly as 'Every Man Dies For Himself Alone'. What do you think this means? How does it apply to the characters' fates?

7. What is your reaction to the more minor characters in the novel: the postwoman Eva Kluge and the petty criminals Kluge and Borkhausen? How do you see the role they play in the story?

8. Hans Fallada was said to have written Alone in Berlin in just twenty-four days. How do you think this is reflected in the way the novel is written?

9. The story of the Quangels is based on events that occurred to a real-life couple in wartime Berlin. Does this change your reading of the novel in any way, and if so, how?

1. What is your reaction to the portrayal of the Quangels' marriage in the novel? Did your view of their relationship change during the course of the story?

2. The idea of resistance is key to Alone in Berlin. How successful do you feel the Quangels' act of resistance to the Nazi regime is? Did they ultimately achieve anything?

3. The novel opens by describing the residents of a house on Jablonski Street. What kind of atmosphere did you think this description creates? How does the novelist portray life in wartime Berlin?

4. At one point in the novel Otto Quangel states that 'No one could believe in God any more'. What is your view of this statement? Do you think Alone in Berlin portrays a godless world? Is it possible to retain a sense of faith when you are surrounded by cruelty?

5. What is your reaction to the character of the Gestapo Inspector Escherich? Did you have any sympathy for his predicament? Do you think it is possible to sympathize with an 'evil' character?

6. The novel's German title translates directly as 'Every Man Dies For Himself Alone'. What do you think this means? How does it apply to the characters' fates?

7. What is your reaction to the more minor characters in the novel: the postwoman Eva Kluge and the petty criminals Kluge and Borkhausen? How do you see the role they play in the story?

8. Hans Fallada was said to have written Alone in Berlin in just twenty-four days. How do you think this is reflected in the way the novel is written?

9. The story of the Quangels is based on events that occurred to a real-life couple in wartime Berlin. Does this change your reading of the novel in any way, and if so, how?

^ Some great questions there Ally.

^ Some great questions there Ally.I'll have to come back to those. Perhaps I'll try and answer one a day. For now here are my thoughts on the book...

Hans Fallada was all but forgotten outside Germany when this 1947 novel, Alone in Berlin (US title: Every Man Dies Alone), was reissued in English in 2009, whereupon it became a best seller and reintroduced Hans Fallada's work to a new generation of readers.

I came to this book having read More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada by Jenny Williams, which was the perfect introduction into the literary world of Hans Fallada.

Alone In Berlin really brings alive the day-to-day hell of life under the Nazis - and the ways in which people either compromised their integrity by accepting the regime, or, in some cases, resisted. The insights into life inside Nazi Germany are both fascinating and appalling. The venom of Nazism seeping into every aspect of society leaving no part of daily existence untouched or uncorrupted.

Alone In Berlin is also a thriller, and the tension starts from the first page and mounts with each passing chapter. I can only echo the praise that has been heaped on this astonishingly good, rediscovered World War Two masterpiece. It's a truly great book: gripping, profound and essential.

5/5

I do read German but my knowledge of the language is pretty rusty these days, so I wasn't sure whether to bother with the original or just read it in translation.

I do read German but my knowledge of the language is pretty rusty these days, so I wasn't sure whether to bother with the original or just read it in translation. However, via the "look inside" feature at Amazon, I've just been looking at the first page in German compared to the first page of the Michael Hofmann translation, and am immediately noticing a lot of changes and cuts.

For instance, it's mentioned twice on that first page that the postwoman Eva is herself a member of the Nazi party - she had to join in order to work for the post office - but both mentions are cut out of the English text. Also quite a bit of conversation is cut out - so I think I will fork out the £8 for the German text and try to read the two together.

My answers to Ally's questions...

My answers to Ally's questions...1. What is your reaction to the portrayal of the Quangels' marriage in the novel? Did your view of their relationship change during the course of the story?

I was quite touched by their marriage. Although on the face of it they might appear to be an ill matched couple they clearly understand each other and have grown very used to each other. Interestingly, they both - separately and independently - appear to come to the conclusion that they should do something to oppose the Nazi regime once their son is killed.

The genuine love between them became far more apparent as the novel unfolds however, even at the outset, I realised it was there, so no, my view of their relationship did not change during the course of the story. That said, I was very touched when Anna needed to know and believe that Otto was still alive.

2. The idea of resistance is key to Alone in Berlin. How successful do you feel the Quangels' act of resistance to the Nazi regime is? Did they ultimately achieve anything?

This is a hard question to answer. On one level their actions were futile, however one of the things that the novel so wonderfully communicates is that you are either complicit in the regime or you do something to oppose it - there is no other option and, once an individual has decided to oppose a regime then he or she has to do something, no matter how small. I have returned my copy to the library, otherwise I would find the part where Otto addresses this very point in a discussion with his first cell mate.

3. The novel opens by describing the residents of a house on Jablonski Street. What kind of atmosphere did you think this description creates? How does the novelist portray life in wartime Berlin?

The atmosphere echoes that experienced by Fallada himself. One of being constantly observed and always at risk of being denounced by neighbours. A world of fear and suspicion, and a place where bullies, snoops and evil prosper.

4. At one point in the novel Otto Quangel states that 'No one could believe in God any more'. What is your view of this statement? Do you think Alone in Berlin portrays a godless world? Is it possible to retain a sense of faith when you are surrounded by cruelty?

My view of this statement is that it is completely understandable and would probably also apply to any totalitarian regime. I imagine it is very difficult to retain a sense of faith when you are surrounded by cruelty.

5. What is your reaction to the character of the Gestapo Inspector Escherich? Did you have any sympathy for his predicament? Do you think it is possible to sympathize with an 'evil' character?

He was vile, although he did gain an insight into the perspective of his victims once the Gestapo got to him. He was never quite the same again and I felt some sympathy with his plight at this point.

6. The novel's German title translates directly as 'Every Man Dies For Himself Alone'. What do you think this means? How does it apply to the characters' fates?

I think it refers to the way that all anyone can ever really do is be accountable for his or her own actions and conduct. Otto and Anna exemplify this message.

7. What is your reaction to the more minor characters in the novel: the postwoman Eva Kluge and the petty criminals Kluge and Borkhausen? How do you see the role they play in the story?

The "minor characters" are very significant, and each adds a richness to this wonderful book.

8. Hans Fallada was said to have written Alone in Berlin in just twenty-four days. How do you think this is reflected in the way the novel is written?

I find that surprising, bordering on unbelievable. I can detect no signs of haste. If it's true it only adds to the book's many qualities.

9. The story of the Quangels is based on events that occurred to a real-life couple in wartime Berlin. Does this change your reading of the novel in any way, and if so, how?

I was amazed that they carried on their campaign and might have found this the most implausible part of the novel were it not for the fact that it was based on a real case, that of Otto and Elise Hampel, a working class couple in Berlin, who did exactly what the Quangels do in the novel. It makes the book even more interesting and impressive.

I read this a while ago, but it is one of those novels which stay with you. Interesting especially as it was written in the period it was set and so you really get a sense of place and time.

I read this a while ago, but it is one of those novels which stay with you. Interesting especially as it was written in the period it was set and so you really get a sense of place and time.

^ I read somewhere that the Hofmann translation was very good in terms of bringing the nuances to life, and appropriate use of equivalent English vernacular, so I'm quite surprised to read Judy's comments.

^ I read somewhere that the Hofmann translation was very good in terms of bringing the nuances to life, and appropriate use of equivalent English vernacular, so I'm quite surprised to read Judy's comments. Eva's membership of the party is mentioned somewhere in the early part of the novel - she later leaves. At least I think so, I might be misremembering.

Like Val, I'd be interested in more comparison Judy.

There is a cool matter-of-factness to the Quangel's interactions with one another (...and indeed between other characters too) and I can't work out whether this is illustrative of a cultural characteristic of the German people or is a more specific result of the place and times the book is set or even if it was a deliberate author choice for the characterisation.

^ I think this quote beautifully illustrates the love that lies deep below the surface of the Quangel's interactions - and in particular the love that Anna has for the taciturn Otto...

^ I think this quote beautifully illustrates the love that lies deep below the surface of the Quangel's interactions - and in particular the love that Anna has for the taciturn Otto...“Anna Quangel wishes she could stroke her husband's hand, but she doesn't dare. She just brushes it, as if by accident, and says, 'Oh, sorry, Otto!' He looks at her in surprise, but doesn't say anything. They walk on.”

I think their undemonstrative style comes primarily from Otto's personality - and Anna's willingness to adapt. I think she would probably be quite different if she'd married a different man.

My German can get me coffee or a beer, that is my level sadly, so I'll be reading the English version.

My German can get me coffee or a beer, that is my level sadly, so I'll be reading the English version.

I started just a few pages. It seems like it could be one I could get into, I'll just have to see if time will allow me to do so.

1. What is your reaction to the portrayal of the Quangels' marriage in the novel? Did your view of their relationship change during the course of the story?

1. What is your reaction to the portrayal of the Quangels' marriage in the novel? Did your view of their relationship change during the course of the story?The Quangels have a strong marriage, they have been together a long time and obviously care about each other, but are not that demonstrative. I agree with those who have said that this undemonstrativeness is mainly because of Otto's character and I think this may have been quite usual for men of his generation.

Fallada is trying to show them as ordinary people who do something extraordinary.

I don't see the relationship changing much, they do something together, so look closer and communicate more, but that closeness was always there and they have a way to express it.

2. The idea of resistance is key to Alone in Berlin. How successful do you feel the Quangels' act of resistance to the Nazi regime is? Did they ultimately achieve anything?

2. The idea of resistance is key to Alone in Berlin. How successful do you feel the Quangels' act of resistance to the Nazi regime is? Did they ultimately achieve anything?The Quangel's resistance appears to have little effect (view spoiler), but that is not really the point. The author is saying that people can make a stand for what they believe in, even if they stand alone.

^ Great to see so many BYTers getting involved. I think it's a stunning book and there's certainly plenty to discuss. I look forward to reading more thoughts, feelings and ideas as other BYTers work their way through the book.

^ Great to see so many BYTers getting involved. I think it's a stunning book and there's certainly plenty to discuss. I look forward to reading more thoughts, feelings and ideas as other BYTers work their way through the book.Val wrote: "The Quangel's resistance appears to have little effect (view spoiler), but that is not really the point. The author is saying that people can make a stand for what they believe in, even if they stand alone. "

Spot on Val. Interestingly at first I wondered what they were doing, and why they didn't continue to keep their heads down and avoid risk, but the book convinced me that there was no halfway house in that kind of regime. You were either complicit or you resisted, and any kind, thoughtful, considerate, humane person had to resist.

I did wonder about the little glimmer of hope at the end. The one happy story, and whether that was a conscious story thread so the story's conclusion included some explicit hope and redemption for some of the characters.

^

^ “No one could risk more than his life. Each according to his strength and abilities, but the main thing was, you fought back.” - Otto Quangel

Here's a question..

Hans Fallada was all but forgotten outside Germany when this 1947 novel - Alone in Berlin / Every Man Dies Alone - was reissued in English in 2009, whereupon it became a best seller.

What do you think it is about Hans Fallada's book that made it resonate with a new generation of readers?

Interestingly, the release of Michael Hofmann’s splendid translation of “Every Man Dies Alone” came with the simultaneous publication of excellent English versions of Fallada’s two best-known novels, “Little Man, What Now?” (translated by Susan Bennett) and “The Drinker” (translated by Charlotte and A. L. Lloyd).

My own answer, is that now, 70 or so years later, we can get a handle on the actions, motivations and private terrors of Berliners who almost all now dead, and so really understand the day-to-day wickedness of the Nazi regime. And, having read the splendid biography of Fallada - More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada by Jenny Williams - I knowthat Fallada witnessed a lot of what he details firsthand. He chose not to leave Nazi Germany, although he had the chance.

There have been a lot of successful crime series set in Nazi Germany - it is almost a sub-genre, but this has the immediacy of someone who was there. You cannot fake real fear and reading this makes that era suddenly real. I feel his re-discovery was so successful because less and less people are alive who were really involved. This novel is also an important historical document.

There have been a lot of successful crime series set in Nazi Germany - it is almost a sub-genre, but this has the immediacy of someone who was there. You cannot fake real fear and reading this makes that era suddenly real. I feel his re-discovery was so successful because less and less people are alive who were really involved. This novel is also an important historical document.

I thought this book was great. It gave me a real sense of what it must have been like to live in an atmosphere of constant fear. I kept wondering how I would have responded if I'd lived in Nazi Germany. Would I have had the courage and integrity of the Quangels, or would I have been more like Enno Kluge? Of course, I'd like to think I would have been brave, but who knows. The Quangels paid a terrible price for their resistance.

I thought this book was great. It gave me a real sense of what it must have been like to live in an atmosphere of constant fear. I kept wondering how I would have responded if I'd lived in Nazi Germany. Would I have had the courage and integrity of the Quangels, or would I have been more like Enno Kluge? Of course, I'd like to think I would have been brave, but who knows. The Quangels paid a terrible price for their resistance.I've read that in the gas chambers, people climbed on top of others, doing everything possible to live for an extra moment--such is the power of our survival instinct. If you're still struggling to live when your death is an absolute certainty, how truly exceptional it would be to take unnecessary risks....How much easier to just keep quiet and try to be invisible.

One of the things that struck me most was how many of the characters were at heart decent people, paralyzed by fear. There were certainly some evil characters, but mainly people were just weak, hoping to survive as painlessly as possible. Fallada showed what good there was in people. Among some of the more positive characters, we saw Judge Fromm, Otto's second cell mate, Eva Kluge, Fraulein Hetty. Even Escherich seemed less evil than caught up in his own fear. The author--who had lived in this fraught environment himself--hadn't given up on humanity. I liked that he wrote that the book was "dedicated as it is to life, invincible life, life always triumphing over humiliation and tears, over misery and death." That positive vision of humanity, held amidst all the horrors of that time, reminded me of Anne Frank's comment that "in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart."

All in all, a gripping, thought-provoking read.

I've now really started reading this book - I needed to finish another couple of books first! - and am finding myself gripped by it. So far I've only managed to read four chapters in German on my Kindle, because I read German quite slowly, so it will probably be ages before I finish.

I've now really started reading this book - I needed to finish another couple of books first! - and am finding myself gripped by it. So far I've only managed to read four chapters in German on my Kindle, because I read German quite slowly, so it will probably be ages before I finish. I'm not reading all of it in translation too, just using the English text to refer to, but I have noticed that there are quite a few passages in the German which aren't there in the translation. I don't know why this is - it's possible that there is more than one German edition and I've got one with extra pieces added back in, or maybe the English publisher wanted a shorter text?

Since Val and Nigeyb both asked how the translation compares with the original, I thought you might be interested to see quite a long passage from Chapter 3 that isn't included in the translation, about how Anna was involved with the women's service (apparently some kind of Nazi front organisation, like the work organisation that Otto belongs to) before her son's death.

This is mainly my own translation, so apologies that it sounds a bit awkward - but hopefully anyone interested will get the gist! Parts of the first paragraph (the sections in italic) are from the Hofmann translation.

" Anna knew that perfectly well, which is why she should never have said that thing: “You and your Führer!” With Anna it had all happened quite differently. She had taken on her office in the women's service of her own free will, she hadn't been forced as he was. God, yes, he understood how she had come to that. All her life she had been in service, first in the country, then here in Berlin, all her life it had been Do this, do that. She didn't have much of the say in their marriage either, not because he always ordered her about, but because, as the principal breadwinner, things were run around him.

But now she had this office in the women's service, and, even if she had to take her orders from above here too, she also had a great number of girls and women and even fine ladies under her, whom she now commanded. It gave her enjoyment that she could take a lazy do-nothing with her fingernails painted red and send her into a factory. If anybody could say something like “You and your Führer!” about either of the Quangels at all, then it should have been said of Anna first.

Admittedly, she too had long ago found a fly in the ointment. For instance, she had noticed, that many of the fine ladies simply didn't let themselves be sent out to work, because they had good friends on high. Or it angered her that the same people always came along when warm underwear was being handed out, and they were the ones carrying a party book. Anna also thought that the Rosenthals were respectable people and hadn't deserved their fate, but despite that she never thought of giving up her office. She had only recently said that the Führer just didn't know what sort of filthy tricks his people were playing down there. The Führer couldn't know everything and his people were simply lying to him."

The translation resumes here, with “But now Ottochen is dead” - but there is another deleted line at the end of that paragraph, after “Maybe Anna won't ever get back to being her old self again”:

“It had come from too deep within her, that cry 'You and your Hitler'. It had sounded like hatred.”

Apologies that this is such a long posting, but I thought it was quite interesting. I think Anna seems a more complicated character here than she is when her membership in the women's service is cut out, although of course it may be mentioned later on.

Thanks very much for that Judy.

Thanks very much for that Judy.I agree that it makes Anna more complex and conflicted, although it keeps in that Anna's over-riding loyalty is to her family I wonder why it was cut out.

I think I've now found the answer to the cuts and it seems they were made by Fallada himself - the Guardian website has a very interesting webchat with publisher Dennis Johnson, where he says there were different German editions and the English translation is based on Fallada's final text.

I think I've now found the answer to the cuts and it seems they were made by Fallada himself - the Guardian website has a very interesting webchat with publisher Dennis Johnson, where he says there were different German editions and the English translation is based on Fallada's final text. It sounds as if there are differences of opinion over which text is preferable, with some claims that the earlier text is the "uncensored" one and this being the version which was chosen for translation into Norwegian. However, Johnson prefers the shorter version. I wonder if the longer version will eventually be translated into English too?

Very interesting, Judy. Thanks! I had no idea the translation would change things so much...I always try to read in the original language whenever possible, but since I know only French, I often have to resort to translations. I have long noticed the difference between the original and the translation, but only in terms of the writing style, the nuances, the atmosphere--not the actual story. Your comments make me wonder how much I have missed in Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Cervantes, etc. Ah well, better to suffer the limitations of translation than to miss out altogether...

Very interesting, Judy. Thanks! I had no idea the translation would change things so much...I always try to read in the original language whenever possible, but since I know only French, I often have to resort to translations. I have long noticed the difference between the original and the translation, but only in terms of the writing style, the nuances, the atmosphere--not the actual story. Your comments make me wonder how much I have missed in Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Cervantes, etc. Ah well, better to suffer the limitations of translation than to miss out altogether...

Thanks, Val - I'm interested that you also feel this makes Anna more conflicted. I had noticed that quite a few of the changes are along the same lines, ie, cutting out mentions of involvement by the sympathetic characters with the Nazis. Now that I know Fallada himself made the cuts, the changes are all the more fascinating. I'm not sure if the shorter version is available in Germany as well as the longer one.

Thanks, Val - I'm interested that you also feel this makes Anna more conflicted. I had noticed that quite a few of the changes are along the same lines, ie, cutting out mentions of involvement by the sympathetic characters with the Nazis. Now that I know Fallada himself made the cuts, the changes are all the more fascinating. I'm not sure if the shorter version is available in Germany as well as the longer one.

Confusingly, I think the shorter version with the cuts was the first one published in Germany, but the longer "uncensored" version, though published second, was written first! Thanks, Barbara - I'm also relieved to learn that the changes aren't all down to the translation.

Confusingly, I think the shorter version with the cuts was the first one published in Germany, but the longer "uncensored" version, though published second, was written first! Thanks, Barbara - I'm also relieved to learn that the changes aren't all down to the translation.

I started reading this a couple days ago and I'm loving it! It gives a sense of the persecution and paranoia that so many citizens felt during Hitler's regime. It makes even any small act of defiance extremely brave in my opinion.

I started reading this a couple days ago and I'm loving it! It gives a sense of the persecution and paranoia that so many citizens felt during Hitler's regime. It makes even any small act of defiance extremely brave in my opinion. Nigeyb, I agree completely with your comment about the "you either support the Nazi's or are actively

resisting" comment. Trudel and her husband were looked down on (by their former coworkers) for their romance and starting a family, rather than being active with a resistance. And that idea went the same way for the Nazi's. If you weren't a fully involved member of the party, and sometimes even if you were, they arrested you. Case in point, Escherich, or even the later arrest of Trudel. Fallada seriously did a great job with the sense of persecution in this novel, as everyone else has already said. It's terrifying.

Thanks Amanda. I enjoyed reading your comments which I completely agree with. I am so pleased you are enjoying the book. I feel quite evangelical about it and so am pleased to see another BYTer getting involved.

Thanks Amanda. I enjoyed reading your comments which I completely agree with. I am so pleased you are enjoying the book. I feel quite evangelical about it and so am pleased to see another BYTer getting involved.Amanda wrote: "It's terrifying."

Yes it is.

I'm getting on with this rather slowly because of reading it in German, plus not having much time at the moment to read... but, all the same, am finding it a wonderful read. It strikes me that the language is incredibly colloquial and simple, just how people speak, which makes it easier for me to read than most German books.

I'm getting on with this rather slowly because of reading it in German, plus not having much time at the moment to read... but, all the same, am finding it a wonderful read. It strikes me that the language is incredibly colloquial and simple, just how people speak, which makes it easier for me to read than most German books. The chapter where Emil and Enno go and rob the elderly Jewish lady's apartment and enjoy themselves so much is absolutely chilling.

It seems as though it was difficult to be 'invisible' in that world. Trudel and Karl were doing their best to keep their heads down and not get involved, but they were accidentally drawn in. I've never read anything about what it was like in Germany during the war, I'm finding it fascinating and horrifying. I've nearly finished it now, am hoping to get to the end today.

It seems as though it was difficult to be 'invisible' in that world. Trudel and Karl were doing their best to keep their heads down and not get involved, but they were accidentally drawn in. I've never read anything about what it was like in Germany during the war, I'm finding it fascinating and horrifying. I've nearly finished it now, am hoping to get to the end today.

I picked this up from the library this afternoon and I'm really looking forward to starting it next. I hadn't planned to join in, as I have so many other books waiting to be read, but it sounds like something I'll love.

I picked this up from the library this afternoon and I'm really looking forward to starting it next. I hadn't planned to join in, as I have so many other books waiting to be read, but it sounds like something I'll love. Lots of very interesting comments above. I'll attempt to answer some of the questions once I've finished.

Judy wrote: "I'm getting on with this rather slowly because of reading it in German, plus not having much time at the moment to read... but, all the same, am finding it a wonderful read. It strikes me that the language is incredibly colloquial and simple, just how people speak,"

Judy wrote: "I'm getting on with this rather slowly because of reading it in German, plus not having much time at the moment to read... but, all the same, am finding it a wonderful read. It strikes me that the language is incredibly colloquial and simple, just how people speak,"The Quangels are not supposed to be highly educated, so it is appropriate that the language reflects that and very interesting that it does, it makes me admire the author's achievement even more.

For anyone who is interested in the different texts of this novel... I've now come across another article about the different versions . This piece in the Guardian argues that the shorter edition translated into English was possibly censored by the original East German publisher and suggests Fallada, who was near death by that time, might not have known about the cuts... although the previous article I posted a link to said that he made the cuts himself!

For anyone who is interested in the different texts of this novel... I've now come across another article about the different versions . This piece in the Guardian argues that the shorter edition translated into English was possibly censored by the original East German publisher and suggests Fallada, who was near death by that time, might not have known about the cuts... although the previous article I posted a link to said that he made the cuts himself! Apparently there is a whole chapter which was cut from the first edition but has now been restored in the latest German text. I'm not quite up to that chapter yet, but will look out for it. It seems to be a very confusing situation with the different versions of the text. Anyway, this article says they are both legitimate texts.

Val, thank you, that's a good point about the language going with the characters. Nigeyb, thanks for saying you are interested in the different versions.

Val, thank you, that's a good point about the language going with the characters. Nigeyb, thanks for saying you are interested in the different versions.The character of Judge Fromm is noticeably different in the two versions of the text. In the longer version, he tells Frau Rosenthal that he used to be known as "bloody Fromm" and "executioner/hanging judge Fromm" and that he has ordered the execution of about 20 people. After that she thinks of him as "bloody Fromm".

"Fromm" means "pious" in German, so to me the juxtaposition of that with "bloody" is quite disturbing - like a bloodstained priest.

I'm really pleased that this book is generating plenty of interest and discussion. It's such a powerful book and one that has stayed with me since I finished it in mid-March. It's a truly great book: gripping, profound and essential.

I'm really pleased that this book is generating plenty of interest and discussion. It's such a powerful book and one that has stayed with me since I finished it in mid-March. It's a truly great book: gripping, profound and essential.

I had hoped to get further into it and brought it with me on my spring "vacation" to visit my mother. I haven't opened it once. I'll probably have to renew this and the Graham Greene book for May.

I had hoped to get further into it and brought it with me on my spring "vacation" to visit my mother. I haven't opened it once. I'll probably have to renew this and the Graham Greene book for May.

^ Your sagely comments are always worth the wait Jan.

^ Your sagely comments are always worth the wait Jan. I just had a quick look on your page to see where you were up to with it and notice you are still currently reading over a thousand books. As ever, I am in awe of your ability to simultaneously read so many books.

I've now read the chapter which was cut from the first edition - it's a great chapter, full of black humour. I do hope it gets included in future English editions - I won't try to translate it, but will just quickly summarise what happens.

I've now read the chapter which was cut from the first edition - it's a great chapter, full of black humour. I do hope it gets included in future English editions - I won't try to translate it, but will just quickly summarise what happens.It's about how Anna manages to leave the Nazi Women's Federation, despite having been a leader in the local group. She wants to leave without alerting anyone to her change of political views, so she decides to get herself thrown out for being over-enthusiastic.

She therefore marches into the house of a rich, beautiful woman married to a leading local Nazi official. Anna starts to deliberately insult this woman, accusing her of being lazy and uncommitted to "our beloved Fuhrer", and orders her to report for work at a factory. The woman is beside herself with rage and gets her husband to phone up Anna's bosses in the women's organisation and complain about her. They go round to see Anna and suggest she 'takes a break' from the Nazi women's group, in the hope that she will leave permanently... which of course was her intention all along!

^ Thanks so much for that Judy. What a marvellous idea by Anna / Fallada to leave the Federation.

^ Thanks so much for that Judy. What a marvellous idea by Anna / Fallada to leave the Federation. Perhaps, like we get with some DVDs, there might be the equivalent of an expanded Director's Cut for readers to enjoy in the future?

Let's hope so, Nigeyb. The Guardian article did say that Penguin is considering adding an appendix with the missing chapter. There is talk of a film being made, so maybe if that happens there will be enough interest for a new edition?

Let's hope so, Nigeyb. The Guardian article did say that Penguin is considering adding an appendix with the missing chapter. There is talk of a film being made, so maybe if that happens there will be enough interest for a new edition?I've just found an article which says two of Fallada's other books, Little Man, What Now? and Wolf Among Wolves were also originally published with sections cut out, which were later restored first in Germany and eventually in translations. But I suppose these things take time - it's only a few years since this one was translated into English at all.

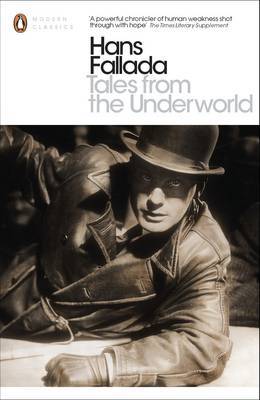

^ Thanks Judy. That's an interesting article that I'd not seen before. You probably also know that there's more Fallada being published, including this recent addition to his books in print...

^ Thanks Judy. That's an interesting article that I'd not seen before. You probably also know that there's more Fallada being published, including this recent addition to his books in print...

Tales from the Underworld by Hans Fallada

^ I love the cover to this new book. Penguin Modern Classics have done a splendid job - as usual.

My GoodReads friend Anna has written a blog post about this latest Fallada reissue Tales from the Underworld...

All of the stories are concerned with life’s struggles. They all focus around the lower echelons of society and illustrate the difficulties of life for those living in Germany during this difficult period of war and depression.

Click here to read Anna's review of Tales from the Underworld

Thanks, Nigeyb - I didn't know this. Very interesting, and I enjoyed Anna's review. Must agree the cover is great, too. Looks as if quite a few of his works haven't been translated at all yet - I should think more will follow after 'Alone in Berlin' sold so well in the UK.

Thanks, Nigeyb - I didn't know this. Very interesting, and I enjoyed Anna's review. Must agree the cover is great, too. Looks as if quite a few of his works haven't been translated at all yet - I should think more will follow after 'Alone in Berlin' sold so well in the UK.

^ You may have seen this in the "M" thread however, as we were discussing the cover to Tales from the Underworld, I thought I'd also mention here that it is a still from Fritz Lang's film "M" which, coincidentally, we are watching and discussing here at BYT during June 2014.

^ You may have seen this in the "M" thread however, as we were discussing the cover to Tales from the Underworld, I thought I'd also mention here that it is a still from Fritz Lang's film "M" which, coincidentally, we are watching and discussing here at BYT during June 2014.I think "M" makes a perfect cinematic companion piece to the books and stories of Hans Fallada.

Come and get involved...

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

By the by, how great was Every Man Dies Alone by Hans Fallada? One of the many wonderful fiction reads we're already enjoyed in 2014.

Judy, Jan and Pink - did you finish this Every Man Dies Alone? What did you conclude?

I'm still reading it, Nigeyb - as I'm reading in German it is taking me a long time, but I'm still very impressed by it.

I'm still reading it, Nigeyb - as I'm reading in German it is taking me a long time, but I'm still very impressed by it.

Books mentioned in this topic

Alone in Berlin (other topics)Every Man Dies Alone (other topics)

Tales from the Underworld: Selected Shorter Fiction (other topics)

Every Man Dies Alone (other topics)

Tales from the Underworld: Selected Shorter Fiction (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Hans Fallada (other topics)Hans Fallada (other topics)

Hans Fallada (other topics)

Jenny Williams (other topics)

Hans Fallada (other topics)

More...

Please note that if you're reading in the UK the book is published under the title...

Enjoy!