The Pickwick Club discussion

In which Oliver Twist is covered

>

May 8 -14 Book the First, Chapters the Eighth through the Fifteenth

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Jonathan

(new)

May 08, 2013 11:31PM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

On Mr. Brownlow and his motives for taking an interest in Oliver

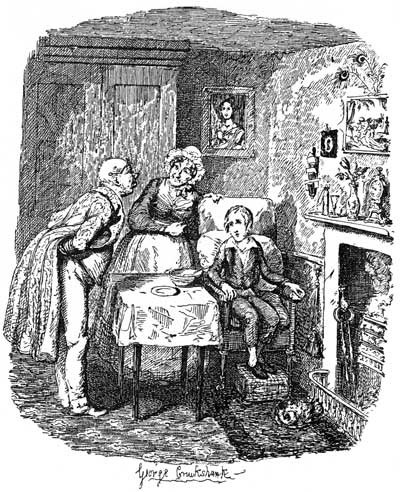

On Mr. Brownlow and his motives for taking an interest in OliverMr. Brownlow seems to be, at a very early stage, reminded of somebody very dear to him by Oliver's looks. At the beginning of Chapter 12 he tries to find out who it actually is that Oliver Twist reminds him of, but he does not succeed yet.

In chapter 14, Mr. Brownlow's motives for taking an active interest in Oliver become more obvious still when he says: "'I have been deceived, before, in the objects whom I have endeavoured to benefit; but I feel strongly disposed to trust you, nevertheless; and I am more interested in your behalf than I can well account for, even to myself. The persons on whom I have bestowed my greatest love, lie deep in their graves; but although the happiness and delight of my life lie buried there, too, I have not made a coffin of my heart, and sealed it up, for ever, on my best affections. Deep affliction has but strengthened and refined them.'"

Later on he says, "'I only say this, because you have a young heart; and knowing that I have suffered great pain and sorrow, you will be more careful, perhaps, not to wound me again. You say you are an orphan, without a friend in the world; all the inquiries I have been able to make, confirm the statement. Let me hear your story; where you come from; who brought you up; and how you got into the company in which I found you. Speak the truth, and you shall not be friendless while I live.'"

Here it becomes clear that Mr. Brownlow sees Oliver as a kind of stand-in for someone else he has loved and he has been disappointed in.

I have to admit that I disbelieve the possibility of Oliver's trip to London. 70 miles on foot for a boy his age with almost no food, no bed, I think he would either have given up or been picked up as a vagrant long before he got to London. Willing suspension of disbelief is one thing, but this was something, for me, beyond that.

I have to admit that I disbelieve the possibility of Oliver's trip to London. 70 miles on foot for a boy his age with almost no food, no bed, I think he would either have given up or been picked up as a vagrant long before he got to London. Willing suspension of disbelief is one thing, but this was something, for me, beyond that.

Everyman wrote: "I have to admit that I disbelieve the possibility of Oliver's trip to London. 70 miles on foot for a boy his age with almost no food, no bed, I think he would either have given up or been picked u..."

Everyman wrote: "I have to admit that I disbelieve the possibility of Oliver's trip to London. 70 miles on foot for a boy his age with almost no food, no bed, I think he would either have given up or been picked u..."In that respect, the film version by Roman Polanski was very clever, because Polanski gave Oliver's journey quite some room, and he even showed how Oliver spent a night in an old woman's house, where he recovered to a certain degree.

On symbols and all that

On symbols and all thatIn the thread on the first seven chapters Jonathan started listing important narrative devices that Dickens used in OT, one of the foremost being symbolism.

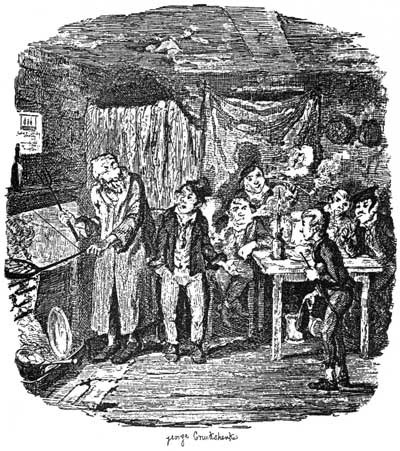

One of the most haunting of Dickens's villains is probably Fagin. This is probably because, as he is a major threat to Oliver and as he has specialized on making children into thieves, he embodies some of our childhood fears (bogeyman). But Dickens even goes one step further as he invests Fagin with symbols that are normally reserved for the Devil. When we first meet him, we find him roasting some sausages on an open fire, "with a toasting fork in his hand", which seems to be so important to Dickens that it is mentioned two more times in the course of the text. In the following chapter (9) we find Fagin equipped with a fire-shovel. - Also the term the merry old gentleman seems to be a euphemistic term for the Devil - in line with Old Harry, Old Nick, Old Scratch -, but as a non-native speaker I would not stand or fall by it.

So all in all, we seem to have a super-villain here, who is all the more terrible as he is seen through the eyes of a child - comparable to one of my favourite film villains, the menacing Preacher (Robert Mitchum) in The Night of the Hunter.

Another interesting scene which could be read symbolically is the beginning of Chapter 15, which finds Bill Sikes in a terrible fight with his malevolent dog. This scene succeeds very well in showing how extremely brutal and primitive Sikes is since the reader gains the impression of two beasts fighting each other here.

Another thing that I find hard to believe - apart, maybe, from the fact that a little boy like Oliver could make it from Chatham to London on foot and with hardly any victuals, is that Oliver really seems to believe that the Artful Dodger and Charley Bates are doing an honest day's work, making handkerchiefs.

Another thing that I find hard to believe - apart, maybe, from the fact that a little boy like Oliver could make it from Chatham to London on foot and with hardly any victuals, is that Oliver really seems to believe that the Artful Dodger and Charley Bates are doing an honest day's work, making handkerchiefs.I mean, how dumb must you be in order to think that the two boys have not stolen the handkerchiefs? Why should Oliver have to undo the monographs if they really had been manufactured by Bates and Dawkins? Oliver has to be a long way off the sharpest knife in the drawer - probably already in the drawer next to the drawer with the sharpest knife - in order not to have suspected something irregular about the boys' business before he set out with Dawkins and Bates the first time.

To swallow this is a feat in the suspension of disbelief ;-D

Tristram wrote: "Another thing that I find hard to believe - apart, maybe, from the fact that a little boy like Oliver could make it from Chatham to London on foot and with hardly any victuals, is that Oliver reall..."

Tristram wrote: "Another thing that I find hard to believe - apart, maybe, from the fact that a little boy like Oliver could make it from Chatham to London on foot and with hardly any victuals, is that Oliver reall..."I agree with you. On a basic narrative level, so far, at least, the story is weak. It seems less like a real novel -- and Dickens had plenty of examples of those available to him, starting with Austen - and more like a morality play in narrative form, with stock figures, simplistic characters (either all good or all bad), gross exaggerations, and the like.

It's been many, many years since I read OT, and I'm finding myself surprised that the author who could write such subtle and sophisticated novels as Bleak House and Little Dorrit could also have penned this work.

Maybe things will change as we get deeper into the story -- I'm certainly open to improvement -- but so far, is there a single complex, true to life person in the whole work?

Adam wrote: "I'm not sure if he would have been picked up as a vagrant in those times, but the distance could be done in three days for someone in desperate need. "

Adam wrote: "I'm not sure if he would have been picked up as a vagrant in those times, but the distance could be done in three days for someone in desperate need. "By a semi-starved ten year old boy with no experience at all in walking any distance -- there's no evidence that he was ever allowed out of the workhouse, at the coffin makers he was presumably kept at work indoors except for the few times he was used as a mourner walking (which would have been very slowly) behind the coffin.

Fellow Pickwickians, I have been out of town for a funeral, so I am behind in the discussion and the reading. If anyone wishes to begin the week 3 discussion, feel at liberty to do so; otherwise, I will do so when I return home this weekend.

So am I, Jonathan, and I'm really sorry to hear it was a funeral that kept you from indulging in our Pickwickian discussions.

So am I, Jonathan, and I'm really sorry to hear it was a funeral that kept you from indulging in our Pickwickian discussions.

Adam wrote: "Tristram wrote: "On Mr. Brownlow and his motives for taking an interest in Oliver

Adam wrote: "Tristram wrote: "On Mr. Brownlow and his motives for taking an interest in OliverMr. Brownlow seems to be, at a very early stage, reminded of somebody very dear to him by Oliver's looks. At the b..."

It is definitely quite startling to notice how our lives may sometimes become unhinged by the most unlikely of coincidences - and maybe quite as startling to deny an author the right to make use of these in their stories, but then deny it we do, expecting writers, for some reason, to be more logical and circumspect than life itself.

These coincidences have taught me to be careful how to treat people I've never met before, because, as we say in German, you always meet twice in life ;-) It's like "what goes around comes around", isn't it?

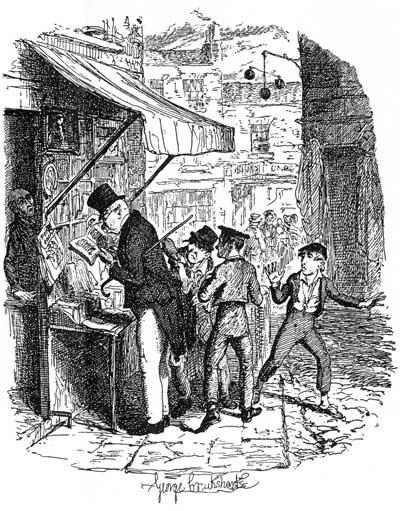

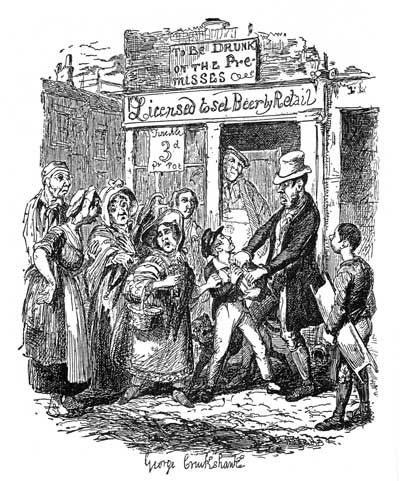

The Artful Dodger is the first person Oliver meets who takes a personal interest in him. He introduces the wandering orphan to Fagin as "my friend, Oliver Twist." I can say this from personal experience: when the hypocritical Pharisees have overlooked, rejected, and mistreated you, it is no great loss, actually more of a gain, to fall in with the heathens, who are so much more apt to befriend you than they are to judge you. This is what's happening here, by the way. The Pharisees running the orphanage and workhouse have misjudged Oliver's past, and have already passed judgment on his future: he will be hanged. This prognostication is the reason they have turned him out. Ever since the man in the great waistcoat prophesied Oliver's end in a noose, they have collectively wanted nothing to do with him.

What is Dickens attempting to say about Victorian Society by demonstrating that the beadle and the parish mistreated and then turned him out, yet a miserable little thief proudly befriended him and lent him a helping hand?

What is Dickens attempting to say about Victorian Society by demonstrating that the beadle and the parish mistreated and then turned him out, yet a miserable little thief proudly befriended him and lent him a helping hand?

One of the things that I find interesting is where Dickens gets his ideas from. We've talked a lot, especially in later chapters, about the amazing coincidences that have come up and their effect on us readers being able to find the book believable. Perhaps the next couple of notes will help:

Fagin's headquarters in Field-lane "had been the location of the hide-out of the notorious eighteenth-century thief Jonathan Wild. Its shops were well known for selling silk handkerchiefs bought from pickpockets." This note from my text (Horn, 495) goes on to share one of Dickens' letters alluding to some of his work being pilfered: "when my handkerchief is gone, that I may see it flaunting with renovated beauty in Field-lane."

Everyman wrote: "is there a single, true to life person in the whole book?..."

This might help. I was intending to put this note anyways, but then I saw your question here. This helped me, not only with the believability of the book, but also with the enjoyability. I was beginning to think that every character was a gross exaggeration of a general type, with no grounds in reality. This is definitely not the case with our ruthless magistrate, Mr. Lang, who is entirely based on a real person who was probably even more severe in reality than even depicted here. In a letter dated June 3, 1837, Dickens wrote to his friend Thomas Haines:

In my next number of Oliver Twist, I must have a magistrate...whose harshness and insolence would render him a fit subject to be 'shewn up'...I have...stumbled upon Mr. Laing of Hatton Garden celebrity.

Allan Stewart Laing (1788-1862) served as a police magistrate from 1820-1838, before being dismissed by the Home Secretary for what sounds like abuse of his power. Dickens even went so far as to ask Haines, an influential police reporter to smuggle him into the Hatton Garden office so he could get an accurate physical description of his character.

Bearing this in mind, we may come to the conclusion that these other apparent exaggerations -Bumble, the mistress of the orphanage, Mrs. Sowerberry, etc.- have their counterparts in reality and may not be exaggerations after all. For example, as far as Bumble is concerned, Dickens had previously studied and sketched the office of beadle in Sketches by Boz. It is possible he observed this hypocritical, harsh behavior at that point.

This might help. I was intending to put this note anyways, but then I saw your question here. This helped me, not only with the believability of the book, but also with the enjoyability. I was beginning to think that every character was a gross exaggeration of a general type, with no grounds in reality. This is definitely not the case with our ruthless magistrate, Mr. Lang, who is entirely based on a real person who was probably even more severe in reality than even depicted here. In a letter dated June 3, 1837, Dickens wrote to his friend Thomas Haines:

In my next number of Oliver Twist, I must have a magistrate...whose harshness and insolence would render him a fit subject to be 'shewn up'...I have...stumbled upon Mr. Laing of Hatton Garden celebrity.

Allan Stewart Laing (1788-1862) served as a police magistrate from 1820-1838, before being dismissed by the Home Secretary for what sounds like abuse of his power. Dickens even went so far as to ask Haines, an influential police reporter to smuggle him into the Hatton Garden office so he could get an accurate physical description of his character.

Bearing this in mind, we may come to the conclusion that these other apparent exaggerations -Bumble, the mistress of the orphanage, Mrs. Sowerberry, etc.- have their counterparts in reality and may not be exaggerations after all. For example, as far as Bumble is concerned, Dickens had previously studied and sketched the office of beadle in Sketches by Boz. It is possible he observed this hypocritical, harsh behavior at that point.

Furthermore, some of these colorful acts of the characters, which we want to chalk up as figments of the author's runaway imagination, are actually real events, with some insignificant alterations to make them the author's own. For example, when Nancy went to the jail to inquire after Oliver, she had a conversation with an inmate who was incarcerated for playing the flute. In November 1835, Dickens had reported on Mr. Liang thowing a muffin-boy in jail "for ringing a muffin-bell in Hatton Garden while Laing's court was sitting." Seeing how Dickens fit these real occurrences into his story lends some credence to the other atrocities, which we do not necessarily know the background for.

In chapter 10, Dickens pointed out the differences between the dungeons reserved for petty thieves and the palaces reserved for hardened felons. This is a recurring theme throughout his works, mainly centering on the horrible treatment of unfortunate debtors (like his own father) and the not-so-harsh-treatment of murderers and rapists. We found this to be the case in Pickwick, and we will revisit this issue again in Little Dorrit. Obviously, this too came straight from the author's personal experiences. This is why, even though there is some truth to the statement, I cannot get over Chesterton calling Dickens a mythologist. For, so much of his material came out of his ordinary, everyday life.

Jonathan wrote: "In chapter 10, Dickens pointed out the differences between the dungeons reserved for petty thieves and the palaces reserved for hardened felons. This is a recurring theme throughout his works, main..."

Jonathan wrote: "In chapter 10, Dickens pointed out the differences between the dungeons reserved for petty thieves and the palaces reserved for hardened felons. This is a recurring theme throughout his works, main..."In my edition, I find a passage like that in Chapter 11, and it even finishes with the words: "Let anyone who doubts this, compare the two." In other words, Dickens claims to be describing, and indicting, actual conditions, and he challenges the readers to take him by his word. This is the realistic side of Dickens's writing, which can also be seen in the way Dickens did research on Mr. Laing, who appears as Mr. Fang, for instance. Of course, one can hardly tell how truthful Dickens's depictions were in every singular case - after all he used to work as a journalist, so exaggeration and simplification were probably not alien to him (cf. Trollope's jabs at Dickens in The Warden).

I don't think, however, that Dickens's wish to indict social injustices and his tendency to base some of his characters on actual persons conflict with Chesterton's characterization of Dickens as a mythologist. Neither would I regard this labelling in as negative a light as you, Jonathan, seem to imply [I hope I didn't get you wrong there, and if I did, remember I am but a humbug, Pickwickially spoken]. In my eyes many of his characters have so much vivacity and power that they tend to have adopted a life of their own, beyond the confines of the stories they were knit into. And so, Fagin, Mrs. Gamp, Mr. Micawber and some others have actually become some sort of myth, i.e. not something to deceive people but to kindle their imagination. Calling Dickens a mythologist does not mean to say, in my opinion, that his writings are completely out of touch with reality. I'd rather regard it as an expression of admiration on Chesterton's part.

I hope your weekend is also full of sunshine and birds' bickerings.

Tristram wrote: "Jonathan wrote: "In chapter 10, Dickens pointed out the differences between the dungeons reserved for petty thieves and the palaces reserved for hardened felons. This is a recurring theme throughou..."

I have not forgotten that you are a humbug, if only in a Pickwickian sense, but I, nevertheless, thank you for the reminder. If Dickens is a mythologist, then that label, too, can only stick to him in a Pickwickian sense. I find that, as we delve deeper into the author's life, and find the true basis of his fictitious characters, and seeing that the real-life counterparts actually performed similar atrocius acts as those of their fictional counterparts, I am able to more readily accept this story as plausible. If Chesterton simply meant to say that Dickens' characters are larger than life, then that is what he should have said. That is the only interpretation of his interesting quote which rings true for me. Now, if we were discussing The Goblin Who Stole a Sexton, the short story included in Pickwick, or The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain, or A Christmas Carol, then I think we could classify Mr. Dickens with Homer and his fellow Greeks. But, when it comes to more serious works, like Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Great Expectations, and the characters therein, I think that we find mythologist a much too narrow classification for the diversified author. Is Pip who was on a quest to be a gentleman and wrestling with his birth and status anything like Beowulf who was wrestling with a beast unlike any that existed during his time? Was David Copperfield who encountered everyday problems like finding a career and securing himself a wife very much like Odysseus who was struggling with Calypso and the other residents of Olympus on his journey back to his wife and family? The stories and characters are so different that I cannot accept such a narrow-minded label on a multi-facited novelist. That would be like saying Dickens was the first true mystery writer because of what happened in Martin Chuzzlewit and his unfinished Edwin Drood. We know that he was so much more than a mystery author. He wrote comedy, but that doesn't make him a comedian. He wrote about ghosts, but that doesn't make him a horror author. There were many marriages in his stories, but I wouldn't call him a romance writer. He wrote about history, but that doesn't make him a history author. Do you see what I am saying? In many of his works and considering many of his diverse characters, the label of mythologist would be equivalent to calling Stephen King a romance novelist. Just because a few stories and a few characters fit the category doesn't make it reasonable to place such a generic term on a man with many different talents, trademarks, and styles.

I have not forgotten that you are a humbug, if only in a Pickwickian sense, but I, nevertheless, thank you for the reminder. If Dickens is a mythologist, then that label, too, can only stick to him in a Pickwickian sense. I find that, as we delve deeper into the author's life, and find the true basis of his fictitious characters, and seeing that the real-life counterparts actually performed similar atrocius acts as those of their fictional counterparts, I am able to more readily accept this story as plausible. If Chesterton simply meant to say that Dickens' characters are larger than life, then that is what he should have said. That is the only interpretation of his interesting quote which rings true for me. Now, if we were discussing The Goblin Who Stole a Sexton, the short story included in Pickwick, or The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain, or A Christmas Carol, then I think we could classify Mr. Dickens with Homer and his fellow Greeks. But, when it comes to more serious works, like Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Great Expectations, and the characters therein, I think that we find mythologist a much too narrow classification for the diversified author. Is Pip who was on a quest to be a gentleman and wrestling with his birth and status anything like Beowulf who was wrestling with a beast unlike any that existed during his time? Was David Copperfield who encountered everyday problems like finding a career and securing himself a wife very much like Odysseus who was struggling with Calypso and the other residents of Olympus on his journey back to his wife and family? The stories and characters are so different that I cannot accept such a narrow-minded label on a multi-facited novelist. That would be like saying Dickens was the first true mystery writer because of what happened in Martin Chuzzlewit and his unfinished Edwin Drood. We know that he was so much more than a mystery author. He wrote comedy, but that doesn't make him a comedian. He wrote about ghosts, but that doesn't make him a horror author. There were many marriages in his stories, but I wouldn't call him a romance writer. He wrote about history, but that doesn't make him a history author. Do you see what I am saying? In many of his works and considering many of his diverse characters, the label of mythologist would be equivalent to calling Stephen King a romance novelist. Just because a few stories and a few characters fit the category doesn't make it reasonable to place such a generic term on a man with many different talents, trademarks, and styles.

Some pertinent points have been made in this thread. Thank you for sharing these ideas Tristram, Jonathan and Everyman. I was particularly interested in the parallels concerning symbols, Tristram, and also the information about the real life characters on whom both the magistrate Mr Fang was based, and also the thief Jonathan Wild as the inspiration for the pickpocket theme, Jonathan. This was new information to me :)

Some pertinent points have been made in this thread. Thank you for sharing these ideas Tristram, Jonathan and Everyman. I was particularly interested in the parallels concerning symbols, Tristram, and also the information about the real life characters on whom both the magistrate Mr Fang was based, and also the thief Jonathan Wild as the inspiration for the pickpocket theme, Jonathan. This was new information to me :)I am pleased to see that all of you at this stage of the novel were now coming round to the idea that perhaps Dickens was not exaggerating as much as you had feared, with his descriptions of the workhouse, and how destitute people were treated in general at that time. Despite Dickens's early journalistic career, I have never doubted that most of what he described was pretty near the truth, merely "selecting highlights" of the scenario for dramatic effect, much as he would have edited the action as a reporter.

Enjoying the original illustrations too, thanks :)

I have nothing to add here, as I posted about Fagin in the previous thread. So on to the next.