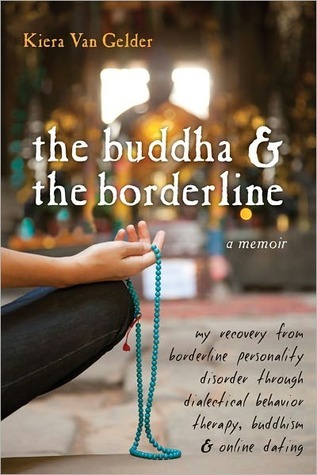

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 10 - February 25, 2024

That’s what closing my eyes felt like when I was six. I wasn’t afraid of the dark; I was terrified of being inside myself.

Everyone is doing the best they can, yet everyone needs to try harder.

I sometimes wonder if I wouldn’t have been better off as a paraplegic or afflicted by some tragic form of cancer. The invisibility and periodicity of my disorder, along with how I often border on normalcy, allows them to evade my need for their understanding.

“I grew up in a very invalidating environment,” I declare. “People didn’t take my problems seriously. I was blamed for everything I did. When I got upset, no one taught me how to take care of myself. And you were gone half the time on your trips around the world, and when you were around, you were constantly preoccupied. Even with you there, you weren’t there. I felt entirely alone.”

“You always blame me for everything.” I deny this. I blame my father a lot too, only he wasn’t around, so she’s the one who actually raised me.

“I’m not going to pretend things didn’t happen just because you don’t like to remember.”

Attachment to your version of reality is a terrible setup. It’s this way for everyone, but especially for us borderlines, because we have such difficulty making room for the perspective of others. Extreme emotion automatically narrows attention.

DBT places so much emphasis on recognizing opposing truths and practicing skills like radical acceptance. You have to let go of absolutes and polarizations.

“I did everything possible to take care of you and Ben. I raised you with love. I took that job at the school to give you a good future. I worked seven days a week so we could stop living on welfare. I sent you to summer camps and after-school programs. I threw birthday parties, went to your soccer games, bought you the clothes you wanted, and took you on trips. I have loved you in every way I could.”

At a certain point, you just have to walk away and let other people have their perspectives, their way of dealing. You can try radical acceptance, obviously. But sometimes it’s just easier to throw up your hands and turn away. Let yourself be baffled and stop trying to make things work.”

No one in recovery wants to think of this struggle as a lifetime condition, nor do our friends, our loved ones, or any of the people who believe in us. But what if it is? What if we will always be challenged and need a wide array of resources and support to keep our symptoms in check? Does that mean we’re screwed?

“Each new challenge,” Dr. Crabtree comments, “brings with it another destabilization and potential loss. And so as you get ‘better,’ there’s an ongoing need for more support, not less.” We all nod at this. It’s so very true. Success and progress would seem to be a good thing, but they can rip the ground away. This takes many forms: being discharged from a program; losing the empathy of others because they now believe we should be over it; and even—or maybe especially—invalidating and berating ourselves because we insist that we should be cured.

Belonging is a primal need. But with BPD, it goes beyond this. To drink from the source of someone else’s presence, no matter how sour it may eventually taste, creates a temporary sense of self.

the goal of DBT skills training as reducing pain and misery by learning how to change emotions, behaviors, and thinking patterns. In the process, you develop the ability to create a life worth living.

while I am doing much better, I still want to punch Taylor or burst into tears whenever he says something “wrong.” I see that I care about people, but only to the extent that they satisfy me. Even in my advocacy efforts, I’m hooked on the effects I have on others, and when I encounter resistance, I don’t feel empathy. I want vindication, and I want to be right.

Four Noble Truths, which were the Buddha’s first teachings after he achieved enlightenment: The first is that suffering is pervasive; the second is that there are causes for this suffering; the third is that this suffering can be stopped; and the fourth is that there is a true path to accomplish this.

“There is nothing to grasp onto because things are always coming and going. If you understand this, you will eventually be able to also recognize the source of things and won’t be caught up in the coming and going. You will ask yourself, ‘Who or what is grasping? And where do all of these things arise from and dissolve into?’”

“You are like everybody else. You suffer from afflictive emotions—from anger, desire, and ignorance. You believe in permanence when there is none; grasp at a solid self although there isn’t one. You have yet to understand the infallibility of karma. But most of all, you do not recognize your true nature, the innate intelligence within: Buddha-nature.”

“Don’t think in terms of good and bad,” Rinpoche instructs. “What you are is primordially pure—absolute perfection. It’s your innate nature. Buddha-nature does not come and go. It’s like the sky, always there: an awareness and clarity that can be temporarily covered by clouds but is ever present. It’s like the sun, never failing to shine.

for some borderlines, the flip side of abandonment fear is the fear of engulfment.

every gain involves a loss. Even though successes are seemingly the building blocks of progress, they also upset the balance, and that makes you more vulnerable.

“I still love him,” I say when she wakes me up and brings me to my old bedroom. “Sometimes love isn’t enough.” She pushes the hair out of my eyes and kisses me goodnight. “You’re going to get through this.”

“It might be just as valid to say that BPD symptoms come out temporarily in anyone who is in extreme pain or who’s going through a terrible loss.”

And only at this minute do I realize that I don’t know his last name, what company he owns, or anything about him, really. He’s just a handsome man who complimented me, and I took him home because I’m lonely.