More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Writers of history often seek the dramatic over the truth. It is a failing of the profession.

He reminded himself to send a man running to inform Petrus, outside the Imperial Precinct, that Jad’s Holy Emperor Apius was dead, that the great game had begun.

Out in the middle of the Hippodrome Forum a Holy Fool, half naked and stinking, had staked a place and was already haranguing the crowd about the evils of racing. The man had a good voice and offered some entertainment . . . if you didn’t stand downwind.

Sarantines weren’t especially rebellious, Bonosus thought wryly, so long as you gave them their free bread each day, let them argue about religion, and provided their beloved dancers and actors and charioteers.

Murder, even in Sarantium, could sometimes be a surprise.

The power of one patrician to complain tended to be offset by the ability of another to bribe or intimidate.

In the hippodromes of the Empire the charioteers raced with Death—the Ninth Driver—as much as with each other.

This was Sarantium. Commoners died to make an example every day.

Valerius didn’t really want him to go, but what was he to do? Ask the other man to sit with him for a night and hold his hand and tell him being Emperor would be all right? Was he a child?

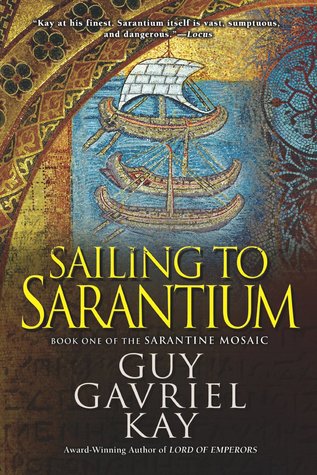

To say of a man that he was sailing to Sarantium was to say that his life was on the cusp of change: poised for emergent greatness, brilliance, fortune—or else at the very precipice of a final and absolute fall as he met something too vast for his capacity.