More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 9 - May 19, 2023

Writers of history often seek the dramatic over the truth. It is a failing of the profession.

Gesius the eunuch, Chancellor of the Imperial Court, pressed his long, thin fingers together piously, and then knelt stiffly to kiss the dead Emperor’s bare feet. So, too, after him, did Adrastus, Master of Offices, who commanded the civil service and administration, and Valerius, Count of the Excubitors, the Imperial Guard.

Apius had reigned thirty-six years. It was hard to believe. Aged, tired, in the spell of his cheiromancers the last years, he had refused to name an heir after his nephews had failed the test he’d set for them. The three of them were not even a factor now—blind men could not sit the Golden Throne, nor those visibly maimed. Slit nostrils and gouged eyes ensured that Apius’s exiled sister-sons need not be considered by the Senators.

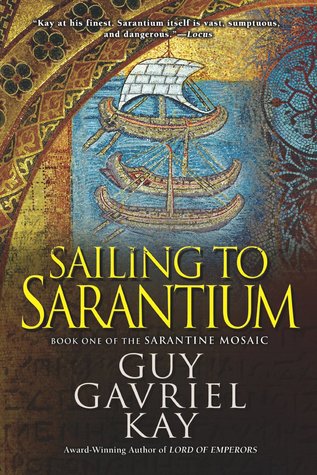

To say of a man that he was sailing to Sarantium was to say that his life was on the cusp of change: poised for emergent greatness, brilliance, fortune—or else at the very precipice of a final and absolute fall as he met something too vast for his capacity.

Sometimes the god entered a man, the clerics taught. And sometimes daemons or spirits did. There were powers in the half-world, beyond the grasp of mortal men.

Men have an aura, a presence to them. It changes little, from childhood to death.

That’s the whole point of alchemy, isn’t it? To transmute one substance into another, proving certain things about the nature of the world. Metals to gold. The dead to life. I have learned to make inanimate substance think and speak, and retain a soul.”

“I honor the old gods, yes. And their philosophers. And believe with them that it is a mistake to attempt to circumscribe the infinite range of divinity into one—or even two or three—images, however potent they might be on a dome or a disk.”

The obvious question.” “And the obvious answer is?” Sarcasm, an old friend, never far away of late.

An artisan could dream of achieving a work that would endure, and be known to have been one’s own. Of what did an alchemist dream?

Amazing, when you thought about it: how quickly-made decisions became the life you lived.

Crispin knew he wanted to achieve something of surpassing beauty that would last. A creation that would mean that he—the mosaic-worker Caius Crispus of Varena—had been born, and lived a life, and had come to understand a portion of the nature of the world, of what ran through and beneath the deeds of women and men in their souls and in the beauty and the pain of their short living beneath the sun. He wanted to make a mosaic that would endure, that those living in after days would know had been made by him, and would honor.

Philosophy could be a consolation, an attempt to explain and understand the place of man in the gods’ creation. It couldn’t always succeed, though. There were times when comfort could only be found in a woman’s laughter, a friend’s known face and voice, shared rumors about the Antae court, even something so simple as a steaming bowl of pea soup at a table with others.

“We worship them as the powers that speak to our souls, if it seems they do.” He surprised himself. “We do so knowing there is more to the world, and the half-world, and perhaps worlds beyond, than we can grasp. We always knew that. We can’t even stop children from dying, how would we presume to understand the truth of things? Behind things? Does the presence of one power deny another?”

Men, when they think in this way—that the crisis, the moment of revealed power, has passed—are as vulnerable as they will ever be. Good leaders of armies at war know this. Any skilled actor or writer for the stage knows it. So do clerics, priests, perhaps cheiromancers. When people have been very deeply shaken in certain ways they are, in fact, wide-open to the next bright falling from the air. It is not the moment of birth—the bursting through a shell into the world—that imprints the newborn gosling, but the next thing, the sighting that comes after and marks the soul.

When you can’t go back and you can’t stay still, you move forward, nothing to think about, get on with it.

They had a phrase along the Imperial road. He’s sailing to Sarantium, they said when some man threw himself at an obvious and extreme hazard, risking all, changing everything one way or another, like a desperate gambler at dice putting his whole stake on the table. That was what he was doing.

The Sarantines were said to be passionate about three subjects: the chariots, dances and pantomimes, and an endless debating about religion.

“I would be a poor creature were I to see value only in bloodshed and war. It is my chosen world, yes, and I would like to leave a proud name behind me, but I would say a man finds honor in serving his city and Emperor and his god, in raising his children and guiding his lady wife toward those same duties.”

There were powers greater than royalty in the world.

It is customary—except perhaps among clerics—to have opinions preceded by knowledge.”

You moved through time and things were left behind and yet stayed with you.

If this was the world as the god—or gods—had made it, then mortal man, this mortal man, could acknowledge that and honor the power and infinite majesty that lay within it, but he would not say it was right, or bow down as if he were only dust or a brittle leaf blown from an autumn tree, helpless in the wind. He might be, all men and women might be as helpless as that leaf, but he would not admit it, and he would do something here on the dome that said—or aspired to say—these things, and more.

The figures of men’s lives were the essence of those lives. What you found, loved, left behind, had taken away from you.