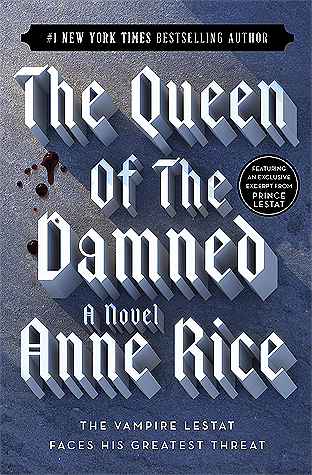

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Anne Rice

Read between

August 11, 2019 - April 13, 2020

The prince is never going to come, everybody knows that; and maybe Sleeping Beauty’s dead.

none of us really changes over time; we only become more fully what we are.

And I want so much to amuse you, to enthrall you, to make you forgive me everything.… Random moments of secret contact and recognition will never be enough, I’m afraid.

We live in a world of accidents finally, in which only aesthetic principles have a consistency of which we can be sure. Right and wrong we will struggle with forever, striving to create and maintain an ethical balance; but the shimmer of summer rain under the street lamps or the great flashing glare of artillery against a night sky—such brutal beauty is beyond dispute.

So until we meet again, I am thinking of you always; I love you; I wish you were here … in my arms.

If the mind can find no meaning, then the senses give it. Live for this, wretched being that you are.

“Goddamn it, do it yourself,” Daniel had roared. “You’re five hundred years old and you can’t use a telephone? Read the directions. What are you, an immortal idiot? I will do no such thing!”

every social problem is observed in relation to ‘norms’ which in fact never existed, people fancy themselves ‘deprived’ of luxuries and peace and quiet which in fact were never common to any people anywhere at all.”

Technological inventions began to obsess Armand, one after the other. First it was kitchen blenders, in which he made frightful concoctions mostly based on the colors of the ingredients; then microwave ovens, in which he cooked roaches and rats. Garbage disposers enchanted him; he fed them paper towels and whole packages of cigarettes. Then it was telephones. He called long distance all over the planet, speaking for hours with “mortals” in Australia or India. Finally television caught him up utterly, so that the flat was full of blaring speakers and flickering screens.

And if Daniel was sluggish, Armand would push him into the shower, soap him all over, rinse him off, drag him out, dry him thoroughly, then shave his face as lovingly as an old-fashioned barber, and finally dress him after carefully selecting from Daniel’s wardrobe of dirty and neglected clothes.

Daniel lived only in two alternating states: misery and ecstasy, united by love.

“Here, snap the clasp if they come near you. Break the vial instantly. And they will feel the power that protects you. They will not dare—” “Ah, you’ll let them kill me. You know you will,” Daniel had said coldly. Shut out. “Give me the power to fight for myself.” But he had worn the locket ever since.

Armand was Daniel’s single oracle, his merciless and all-loving demonic god.

And the wandering started, the escaping, and Armand did not follow him. Armand would wait each time until Daniel begged to come back.

Lips against Daniel’s face, suddenly, ah, that’s better, I like kissing. And snuggling with dead things, yes, hold me.

“You’re dying,” Armand said softly. “ ‘And though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,’ et cetera,” Daniel whispered. His throat was so dry. And his head ached. Didn’t matter saying what was really on his mind. All been said long ago.

“Years ago,” Armand interrupted, “it wouldn’t have mattered to me, all this.” “What do you mean?” “But I don’t want it to end now. I don’t want to continue unless you—” His face changed slightly. Faint look of surprise. “I don’t want you to die.” Daniel said nothing.

I do not understand entirely what is meant by birthday. Was I born into this world on the 21st of September or was it on that day that I departed all things human to become this? My gentlemen parents are forever reluctant to illuminate such simple matters. One would think it bad taste to dwell on such subjects. Louis looks puzzled, then miserable, before he returns to the evening paper. And Lestat, he smiles and plays a little Mozart for me, then answers with a shrug: “It was the day you were born to us.”

we do not really change over time; we are as flowers unfolding, we merely become more nearly ourselves.”

The hall went dark suddenly; and for one split second Khayman thought it was her magic, that some grotesque and vengeful judgment would now be made. But the mortal children all around him knew the ritual. The concert was about to begin! The hall went mad with shrieks, and cheers, and stomping. Finally it became a great collective roar. He felt the floor tremble.

That in all the world no two souls contain the same secret, the same gift of devotion or abandon; that in a common child, a wounded child, he had found a blending of sadness and simple grace that would forever break his heart? This one had understood him! This one had loved him as no other ever had.

Every detail he had sought to preserve forever on canvas; every detail he had certainly preserved in death.

Was nobody ugly ever given immortality?

Eric, bleached by the centuries

“Surrender,” she said, “and I’ll teach you things you never dreamed of. You’ve never known battle. Real battle. You’ve never felt the purity of a righteous cause.”

I was quaking suddenly with fear. Quaking. I knew what the word meant for the first time. I tried to say more but I merely stammered. Finally I blurted it out: “In the name of what morality will all this be done?” “In the name of my morality!” she answered, the faint little smile as beautiful as before. “I am the reason, the justification, the right by which it is done!” Her voice was cold with anger, but her blank, sweet expression had not changed.

“I suspect that someday the scientific nature of spirits will be known. I suspect that they are matter and energy in sophisticated balance as is everything else in our universe, and that they are no more magical than electricity or radio waves, or quarks or atoms, or voices over the telephone—the things that seemed supernatural only two hundred years ago. In fact the poetry of modern science has helped me to understand them in retrospect better than any other philosophical tool. Yet I cling to my old language rather instinctively.

Dear God, dear God! Why did those two words keep coming to me? There was no God! I was in the room with God. She laughed triumphantly.

And then, like a fool, I came out with it. “Do you love me now?” I asked. He smiled; oh, it was excruciating to see his face soften and brighten simultaneously when he smiled. “Yes,” he said. “Want to go on a little adventure?” My heart was thudding suddenly. It would be so grand if—“Want to break the new rules?” “What in the world do you mean?” he whispered. I started laughing, in a low feverish fashion; it felt so good. Laughing and watching the subtle little changes in his face. I really had him worried now.

“Yes or no.” “I’m probably going to regret this, but.…” “Agreed then.”

“You’re a perfect devil, Lestat!” he was saying. “That’s what you are! You are the devil himself!” “Yes, I know,” I said, loving to look at him, to see the anger pumping him so full of life. “And I love to hear you say it, Louis. I need to hear you say it. I don’t think anyone will ever say it quite like you do. Come on, say it again. I’m a perfect devil. Tell me how bad I am. It makes me feel so good!”