More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

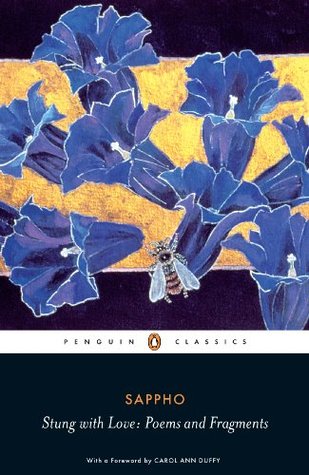

Preface She was born after 630 BC on the Greek island of Lesbos. Plato honoured her as the Tenth Muse, and she was to inspire the naming of both a sexuality and a poetics.

The Ancient Greeks celebrated her as their finest poet and reproduced her image on their coins and vases, and poets from antiquity to the present day have recognized her supreme lyric gift.

The list of poets who have translated her, written versions of her poems or written poems about her, is endless, but includes Ovid, Sir Philip Sidney, John Donne, Alexander Pope, Byron, Coleridge, Tennyson, Thomas Hardy, Christina Rossetti, Amy Lowell, Edna St Vincent Millay, Ezra Pound and many poets writing in our own twenty-first century, notably the distinguished Canadian writer Anne Carson.

ninety per cent of what she wrote is lost to us now.

She would have sung her poems,

As one of a ‘new wave’ of Greek poets, she was one of the first poets to write out of the personal, moving away from the narrative of the gods to the direct and human story of the individual and in doing so she transformed the lyric line.

Because once on a time you were Young, sing of what is taking place, Talk to us for a spell, confer Your special grace.

Her love poems are why she endures and where we recognize ourselves: infatuated and jealous; smitten and fulfilled; brain and tongue shattered by love; wanting to die; remembering past encounters, ‘all beautiful’.

Chronology

A Note on the Text and Translation

It is important to point out that Sappho, as far as we know, did not gather her poems into a collection.

We owe those scraps of Sappho that have come down to us to two Alexandrian scholars, Aristophanes of Byzantium (c. 257–180 BCE) and Aristarchus of Samothrace (c. 220–c. 143 BCE): they arranged the poems which survived to the third and second centuries BCE into nine books.

Even with the Oxyrhynchus fragments, we had until recently only one complete poem, ‘Subtly bedizened Aphrodite’, cited in Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ On Style.

Containing 78 of the roughly 230 fragments, this edition omits most of those that consist only of a word or phrase and all of those that are so tattered as to be indecipherable.

I relied almost entirely on the text of Eva-Maria Voigt1 and note those few instances in which I preferred the text of Lobel–Page2 in the Index of First Lines.

Translations from Classical authors other than Sappho are also my own. Punctuation and capitalization are editorial, and ellipses are used to indicate a lacuna in the source-text.

I have done my best to create a sense of completeness and, on occasion, translated supplements proposed by scholars.

Since all of Sappho’s poems are song-lyrics, I opted to translate them as English lyric poems. Rhyme, an important part of this tradition, is useful in translating Sappho for two reasons: (1) it is one of the ways English writers indicate that something is song-like; and (2) individual lines within Sappho’s poems had emphatic endings, usually two long syllables, and rhyme preserves the integrity of the line within the stanza in much the same way.

Out of a desire to prevent notes from cluttering the translations or gathering in a heap at the back of the book, I decided to present essential information in commentaries facing each poem, fragment or group of fragments.

Sappho continues to amaze readers because she retained the intensity of passion which we associate with the young even into old age. She never grew out of desire, and we can greatly admire her ardour.

Introduction

After his nephew had sung one of Sappho’s songs over wine, Solon of Athens, the son of Execestides, told the boy to teach it to him at once. When someone asked Solon why he was so eager, he answered, ‘So that I may learn it and die.’ Aelian in Stobaeus 3.29.58

Born after 630 BCE, Sappho died around 570. She lived on Lesbos, a large island in the Aegean near the coast of modern Turkey.

According to ancient report, the Lesbians themselves were luxury-loving, and Sappho’s poems present a mixture of Greek customs and exotic Eastern commodities: she sings of ornate headbands and frankincense, and ‘Lydian war cars at the ready’ come to her mind when she imagines a battle array.

We are given six different names for Sappho’s father

We hear of three brothers: Eriguios, Larichos and Charaxus, the eldest. The last, we assume, is the one mentioned in this fragment: Nereids, Kypris, please restore My brother to this port, unkilled.

Ancient and medieval biogaphies attest that Sappho had a daughter, Kleïs (Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 1800, fr. 1 and the Suda Σ 107). The conclusion was most likely drawn from this fragment:

The word pais which I have translated as ‘daughter’ can mean ‘slave’ as well as ‘child’

Furthermore, we cannot be certain that the ‘I’ in this poem was expressing biographical details about the historical Sappho or even that the speaker was not some other character entirely.

Sappho does show interest in the mythic affairs of goddesses with mortals – e.g. Aphrodite’s affair with Adonis and Dawn’s with Tithonous, and her allusions to these myths may explain how later readers came to assume that she herself had an affair with Phaon.

The story that Sappho, in despair over her love for this irresistible youth, died by jumping from Leucas Petra (or the ‘Shining Rock’) into the Aegean probably derives from the fact that she mentions the rock in a poem. In a play by Menander (342–291 BCE) we find: They say that Sappho, while she was chasing haughty Phaon, Was the first to throw herself, in her goading desire, From the rock that shines afar. (Leucadia fr. 258)

This same ‘Shining Rock’ appears in Homer’s Odyssey when the god Hermes escorts the souls of the suitors slain by Odysseus to the Underworld: ‘and they passed by the streams of Okeanos and the Shining Rock and passed th...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The fatal leap provides a moral – the poet of love dies through an excess of passion, and her death serves to refute what she professed in her poetry.

In order to determine, as best as we can, the nature of her group, it will be useful to take a look at society on Lesbos during her lifetime.

Sappho in Context

Throughout the Hellenic world the seventh and sixth centuries BCE were a time of transition from inherited kingships, such as Homer describes in the Iliad and Odyssey, to a world in which tyranny, oliga...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The Archaic Greek world (seventh–mid-fifth centuries BCE) remained the ‘agonistic’ (or competitive) society which we encounter in Homer, with honour ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

with the rise of the polis (or city-state) we find a proliferation of the unconstitutional ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Their government was essentially a monarchy, though the king would meet with the nobles out of courtesy before presenting his policies. Our earliest sources depict the seventh-century Penthelids as cruel – ‘going about striking people with clubs’ (Aristotle, Politics 1311b26).

The other aristocratic families subsequently competed for supremacy and no stable government emerged.

Sappho also clearly belonged to an aristocratic family: she had access to luxury items and education,

During the tyranny of Myrsilus Sappho may have had to go into exile in Sicily, possibly because her family was involved in the plot. In a tattered fragment that refers obscurely to ‘exile’ Sappho seems, for a time, to be cut off from luxuries and utters a frustrated complaint to Kleïs (most likely her daughter):

For all the invective levelled against him in the songs of Alcaeus, Pittacus came to be regarded as one of the Seven Sages of Greece.

Social Context and Sappho’s Group

Since there is evidence both in favour of and against each of these theories, it will be helpful to review them briefly before arriving at a general conclusion. The School

We do not find ‘schools’ as we understand them until late-fifth-century Athens,

The Symposium and the Hetaireia

Drawing on parallels in the poems of Alcaeus and Anacreon, Parker argues that Sappho performed her songs at aristocratic drinking parties called symposia.

Thiasos (or Religious Community)

When writing in the first person Sappho expresses a lover’s passion towards other females, and, as Calame observes, it is difficult to deny ‘that the fragments evoking the power of Eros, to mention only these, refer to a real love that was physically consummated’.