More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

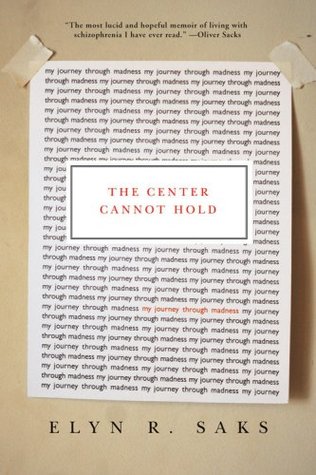

But explaining what I’ve come to call “disorganization” is a different challenge altogether. Consciousness gradually loses its coherence. One’s center gives way. The center cannot hold.

The “me” becomes a haze, and the solid center from which one experiences reality breaks up like a bad radio signal. There is no longer a sturdy vantage point from which to look out, take things in, assess what’s happening. No core holds things together, providing the lens through which to see the world, to make judgments and comprehend risk.

In fact, it is not necessarily true that everything can be conquered with willpower. There are forces of nature and circumstance that are beyond our control, let alone our understanding, and to insist on victory in the face of this, to accept nothing less, is just asking for a soul-pummeling. The simple truth is, not every fight can be won.

Schizophrenia rolls in like a slow fog, becoming imperceptibly thicker as time goes on. At first, the day is bright enough, the sky is clear, the sunlight warms your shoulders. But soon, you notice a haze beginning to gather around you, and the air feels not quite so warm. After a while, the sun is a dim lightbulb behind a heavy cloth. The horizon has vanished into a gray mist, and you feel a thick dampness in your lungs as you stand, cold and wet, in the afternoon dark.

Philosophy and psychosis have more in common than many people (philosophers especially) might care to admit.

When you’re really crazy, respect is like a lifeline someone’s throwing you. Catch this and maybe you won’t drown.

Psychotic people who are paranoid do scary things because they are scared.

They’d known about my hospitalization, but I never did tell them about being psychotic. I wanted them to think well of me. I didn’t want them to look at me and see a crazy person.

I was going to the hospital for the third time, I knew it. I was going to be an inpatient again, and they would make me take drugs. Every nerve in my body was screaming. I didn’t want a hospital. I didn’t want drugs. I just wanted help.

This is a classic bind for psychiatric patients. They’re struggling with thoughts of wanting to hurt themselves or others, and at the same time, they desperately need the help of those they’re threatening to harm. The conundrum: Say what’s on your mind and there’ll be consequences; struggle to keep the delusions to yourself, and it’s likely you won’t get the help you need.

One of the worst aspects of schizophrenia is the profound isolation—the constant awareness that you’re different, some sort of alien, not really human. Other people have flesh and bones, and insides made of organs and healthy living tissue. You are only a machine, with insides made of metal. Medication and talk therapy allay this terrible feeling, but friendship can be as powerful as either.

I’d set goals for myself, meet them successfully, then fall apart at the seams. Once again, everything familiar and comfortable in my life was going away or being left behind. What was ahead was new and frightening. The scaffolding had been removed, and I wasn’t sure that I could sustain the structure all by myself.

Place yourself in the middle of the room. Turn on the stereo, the television, and a beeping video game, and then invite into the room several small children with ice cream cones. Crank up the volume on each piece of electrical equipment, then take away the children’s ice cream. Imagine these circumstances existing every day and night of your life. What would you do?

Who was I, at my core? Was I primarily a schizophrenic? Did that illness define me? Or was it an “accident” of being—and only peripheral to me rather than the “essence” of me? It’s been my observation that mentally ill people struggle with these questions perhaps even more than those with serious physical illnesses, because mental illness involves your mind and your core self as well.

Either I was mentally ill or I could have a full and satisfying personal and professional life, but both things could not be equally true; they were mutually exclusive states of being. To admit one was to deny the other. I simply couldn’t have it both ways. Didn’t anyone understand this?

At which point, I did what by now had become predictable: I became psychotic. Change, good or bad, is never my best thing. “A jumbo jet can sail smoothly through strong and gusty currents,” says Steve. “But a small plane bounces in a small breeze.” Mine was a very small plane; getting tenure was a big, albeit pleasant, wind, and for a few weeks, it threatened to blow me right over.

Ironically, the more I accepted I had a mental illness, the less the illness defined me—at which point the riptide set me free.

When you have cancer, people send flowers; when you lose your mind, they don’t.

It occurs to me that there are often two sets of trickery going on in my life. The illness—the entity—is always just off to the side, just barely out of my sight. But I know it’s there. And it tries to trick me into believing this isn’t the real Will, this isn’t the real Steve, that reality isn’t reality, that I can kill thousands of people with my thoughts, or that I’m profoundly evil and unworthy.

Schizophrenia, the most severe of the psychotic disorders, seems to affect about one out of every hundred people. Some researchers think that it may actually be a whole set of diseases, not just a single disease, which would explain why people with the same diagnosis can seem so different from each other. In any case, whatever schizophrenia is, it’s not “split personality,” although the two are often confused by the public; the schizophrenic mind is not split, but shattered.

If you are a person with mental illness, the challenge is to find the life that’s right for you. But in truth, isn’t that the challenge for all of us, mentally ill or not? My good fortune is not that I’ve recovered from mental illness. I have not, nor will I ever. My good fortune lies in having found my life.