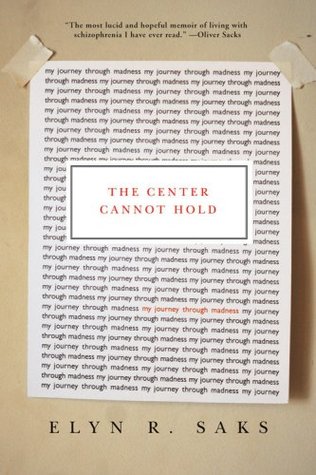

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Elyn R. Saks

Read between

February 11 - June 4, 2021

In spite of my ongoing difficulties ever since undergraduate school (and, in all likelihood, even before that), I hadn’t ever really thought of myself as “ill”—not at Vanderbilt, or even at Oxford, when I was obviously delusional. I truly believed that everyone had the scrambled thoughts I did, as well as the occasional breaks from reality and the sense that some unseen force was compelling them to destructive behavior. The difference was, others were simply more adept than I at masking the craziness, and presenting a healthy, competent front to the world. What was “broken” about me, I

...more

Incredibly, no matter what I said or threatened, I was never restrained. If I expressed a violent impulse, staff encouraged me to rip out the pages of a magazine; if I kept it up, staff steered me to the seclusion room, away from other people. My behavior was no different from what it had been in the ER, or on my initial visit to YPI weeks earlier, or during my three weeks at MU10. But the hospital’s response to the behavior most certainly was. Evidently, the question of whether I was to be restrained or not had more to do with where I happened to be than how I behaved.

Psychiatric patients always have someone (or a whole chorus of someones) telling them what they’re supposed to do. In my own experience, I had discovered that it was much more effective to be asked what I’d like, e.g., “If you could arrange things your way, what would that look like and how do you think we could help you get there?” Indeed, the young woman accepted that she did need treatment—she just wanted, and was entitled to have, a voice in the decision-making about where and how that treatment would happen. It was my job to help her get that. And as empathetic as I felt toward her, I

...more

Thinking about MPD, of course, led me to ask similar questions of myself: Who was I, at my core? Was I primarily a schizophrenic? Did that illness define me? Or was it an “accident” of being—and only peripheral to me rather than the “essence” of me? It’s been my observation that mentally ill people struggle with these questions perhaps even more than those with serious physical illnesses, because mental illness involves your mind and your core self as well. A woman with cancer isn’t Cancer Woman; a man with heart disease isn’t Diseased Heart Guy; a teenager with a broken leg isn’t The Broken

...more

Psychosis sucks up energy like a black hole in the universe, and I’d really outdone myself this time. When I walked, haltingly, down the sidewalk—one careful foot at a time, testing the pavement as though any minute I’d fall through and be swallowed whole—all I could think of was old ladies who walked like this, and how I’d pitied them. The idea of shopping—making lists, getting into the car, actually going someplace and accomplishing something as simple as butter, eggs, bread, and coffee—was overwhelming. Thank God for good friends.

But schizophrenia can knock you out of the loop for as long as three or four years—and for some, forever. In fact, as far as we’ve progressed in research and treatment, recent statistics indicate that only one in five people with schizophrenia can ever be expected to live independently and hold a job.

There’s a powerful urge in each of us to talk about our traumas. “A psychotic episode is like experiencing trauma,” Steve says. I think Steve’s right when he talks about psychosis as being like a trauma. Psychosis does traumatize you, in much the same way that ducking gunfire in a war zone or having a terrible car crash traumatizes you. And the best way to take away the power of trauma is to talk about what happened.

Ironically, the more I accepted I had a mental illness, the less the illness defined me—at which point the riptide set me free.