More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

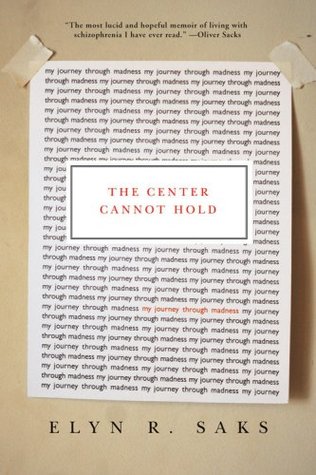

Elyn R. Saks

Read between

April 1 - April 2, 2023

More than once while working with Steve on our LSO cases, I was struck with the absurdities of the mental health care system. Almost every time, there’d come a moment where we’d ask each other, “Wait a minute, just who are the crazy people here?” In one case, the patient’s chart said he was restrained because he wouldn’t get out of bed—which was hardly an instance

of “imminent danger to himself or others” as required by the laws of Connecticut.

The subject of the paper was Daniel Paul Schreber, who at one point in his life had been the chief justice of the supreme court of the German state of Saxony. Schreber had a schizophrenic breakdown, which he wrote about in A Memoir of My Nervous Illness.

if the fire that burned me signaled my destruction, it was also the same fire that got me out of bed in the morning and sent me to the library even on the most frightening days.

July 4 weekend, 1989—one year to the day from the first symptoms of my brain bleed—I boarded the plane for LA, this time for good. And this time, it was a much smoother ride.

The question, of course, was not so much if I would have a psychotic episode as when.

I felt myself slipping. I was in my office, alone, working on an article. I started to sense that the others—the beings who never seemed far off when I got sick—were in the office with me. An evil presence, and growing stronger. Why are they here? Are they trying to take over my mind? Why do they want to hurt me?

As with diabetes, my illness was treatable; as with diabetes, I simply needed to treat it. I’d heard this metaphor before, but it stuck with me this time.

Psychosis sucks up energy like a black hole in the universe, and I’d really outdone myself this time. When

psychoanalysis asks fundamental questions: Why do people do what they do? When can people be held responsible for their actions? Is unconscious motivation relevant to responsibility? And what renders a person not capable of making choices?

and belonging to a respected profession. I knew full well that the stigma that travels with mental illness could trip me up one of these days, but I certainly wasn’t going to collaborate in my own “demise” if I could help it. Even Congress recognized the potential for the damage, when it passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits employers (and schools) from even asking about a psychiatric history. Now, however, the issue was more complicated than my own goals and ambitions. If I had the opportunity to treat patients, would my illness put them at risk? Would my delusional

...more

instant friendships were not only possible for me, but could become precious and lifelong. Alicia brought that lesson home, and right beside her in that same class was Janet. As many gifts as LAPSI has given me in the past few years, these two women were the most unexpected and ultimately the most precious.

With Zyprexa, though, I shut that door and, for the first time in years, it stayed shut. I could take a break, go off duty, relax a little. I couldn’t deceive myself—the illness was still there—but it wasn’t pushing me around as much as it once did. Finally, I could focus on the task at hand, unencumbered by the threat of lurking demons.

Everyone’s mind contained the chaos that mine did, it’s just that others were all much better at managing it than I was.

When you have cancer, people send flowers; when you lose your mind, they don’t.

Many people who suffer from manic depression and depression lead full and rich lives: Journalists Mike Wallace and Jane Pauley, the writer William Styron, and the psychologist and writer Kay Redfield Jamison are just a few prominent examples. Famous historical figures may have suffered from mood disorders as well—Abraham Lincoln, Vincent Van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, and Samuel Johnson. Go to any support group of people with mood disorders and, with some understandable sense of pride, they will name their famous forebears and their contemporary heroes. However, people with thought disorders do not

...more

The media

frenzy that surrounded it only added to the mythology that fuels the stigma: that schizophrenics are violent and threatening. In truth, the large majority of schizophrenics never harm anyone; in fact, if and when they do, they’re far more likely to harm themselves than anyone else.

mental illness diagnosis does not automatically sentence you to a bleak and painful life, devoid of pleasure or joy or accomplishment. I

I write, then, because I know what it’s like to be psychotic. And I know, better than most, how the law treats mental patients, the degradation of being tied to a bed against your will and force-fed medicine you didn’t ask for and do not understand. I want to see that change, and now I actively write and speak out about the crying need for that change. I want to bring hope to those who suffer from schizophrenia, and understanding to those who do not.

“But, Elyn, do you really want to become known as the schizophrenic with a job?” I was taken aback by her question. Is that who I am? Is that only who I am?

I needed to put two critical ideas together: that I could both be mentally ill and lead a rich and satisfying life. I needed to make peace with my demons, so I could stop spending all my energy fighting them. I needed to learn how to navigate my way through a career and relationships with a sometimes tenuous hold on what was real.

Recently, however, a friend posed a question: If there were a pill that would instantly cure me, would I take it? The poet Rainer Maria Rilke was offered psychoanalysis. He declined, saying, “Don’t take my devils away because my angels may flee too.” I can understand that.

Would I still be as creative writing poetry if I took that pill? If not, would I take it? I really don’t know.