More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was then, in 1942, that the classical scholar Edith Hamilton issued an expanded edition of her book, The Greek Way, in which, in the preface, she wrote the following:

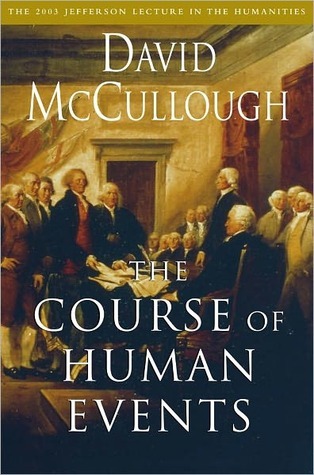

John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence [shown on the cover of this book] has been a main attraction on Capitol tours for a very long time, since 1826.

Yet none of this really matters. What does matter greatly—particularly in our own dangerous,

uncertain time—is the symbolic power of the painting, and where Trumbull put the emphasis. The scene proclaims that in Philadelphia in the year 1776 a momentous, high-minded statement of far-reaching consequence was committed to paper. It was not the decree of a king or a sultan or emperor or czar, or something enacted by a far-distant parliament. It was a declaration of political faith and brave intent freely arrived at by an American congress. And that was something entirely new under the sun.

LORD BOLINGBROKE, the eighteenth-century political philosopher, said that “history is philosophy teaching by examples.”

Jefferson saw history as largely a chronicle of mistakes to be avoided. Daniel Boorstin, the former Librarian of Congress, has wisely said that trying to plan for the future without a sense of the past is like trying to plant cut flowers.

Those we call the Founders were living men. None was perfect. Each had his human flaws and failings, his weaknesses. They made mistakes, let others down, let themselves down.

They were imperfect mortals, human beings. Jefferson made the point in the very first line of the Declaration of Independence. “When in the course of human events . . .” The accent should be on the word human.

But what did they, the Founders, mean by the expression “pursuit of happiness”? It didn’t mean long vacations or material possessions or ease. As much as anything it meant the life of the mind and spirit. It meant education and the love of learning, the liberty to think for oneself.

For Washington, happiness derived both from learning and employing the benefits of learning to further the welfare of others.

The Revolution was another of the darkest, most uncertain of times and the longest war in American history, until the Vietnam War. It lasted eight and a half years, and Adams, because of his unstinting service to his country, was separated from his family nearly all that time, much to his and their distress. In a letter from France he tried to explain to them the reason for such commitment.

I must study politics and war [he wrote] that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study paintings, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.

He knew such wonders of the heavens to be the gifts of God, he wrote, but greatest of all was the gift of an inquiring mind.

Of all the sustaining themes in our story as a nation, as clear as any has been the importance put on education, one generation after another, beginning with the first village academies in New England and the establishment of Harvard and the College of

William and Mary. The place of education in the values of the first presidents is unmistakable.

Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. But then it may be fairly said that Jefferson was a university unto himself.

Wisdom and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties. [Which is to say that there must be wisdom, knowledge, and virtue or all aspirations for

the good society will come to nothing.] And as these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education in various parts of the country, and among the different orders of the people [that is, everyone], it shall be the duty [not something they might consider, but the duty] of legislatures and magistrates in all future periods of this commonwealth to cherish the interests and literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them . . . public schools, and grammar schools in the towns.

to countenance and inculcate the principles of humanity and general benevolence, public and private charity, industry and frugality, honesty [we will teach honesty] . . . sincerity, [and, please note] good humor, and all social affections, and generous sentiments among the people. What a noble statement!

Ben and Me by Robert Lawson.

There was The Matchlock Gun, by Walter D. Edmonds; The Last of the Mohicans, with those haunting illustrations by N. C. Wyeth; the Revolutionary War novel Drums, by James Boyd, with still more Wyeth paintings.