More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

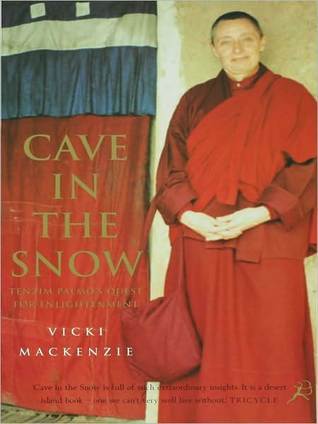

'That's Tenzin Palmo, the Englishwoman who has spent twelve years meditating in a cave over 13,000 feet up in the Himalayas. For most of that time she was totally alone. She has only just come out,'

Retreat, I knew from pitifully small experience, was infinitely hard work involving endless repetition of the same prayers, the same mantras, the same visualizations, the same meditations - day in, day out. You sat on the same cushion, in the same place, seeing the same people, in the same location. For someone steeped in the modern ethos of constant stimulation and rapid change, the tedium was excruciating.

There was calmness there, and kindness, laughter too, but the most outstanding quality was an unmistakable luminosity. The woman virtually glowed.

I learnt that she had been ordained back in 1964, when she was just twenty-one, long before most of us even knew Tibetan Buddhism existed. That made her, I reckoned, the most senior Tibetan Buddhist nun in the Western world.

'I have made a vow to attain Enlightenment in the female form - no matter how many lifetimes it takes,' Tenzin Palmo had said.

The lamas who taught us were male; the Dalai Lamas (all fourteen of them) were male; the powerful lineage holders who carried the weight of the entire tradition were male; the revered Tulkus, the recognized reincarnated lamas, were male; the vast assembly of monastics who filled the temple halls and schools of learning were male; the succession of gurus who had come to the West to inspire eager new seekers were male. Where were the women in all of this?

She was born with the base of her spine twisted inwards and tilted to the left, making the whole of her spinal column off-balance. To compensate she developed round shoulders, the hunched look which she carries to this day. It was an excruciatingly painful condition which left her with weak vertebrae and prone to lumbago.

'There is no way now anyone could tell me that consciousness does not exist after death because I have so much proof again and again that it does.

Ever since I was small I had this conviction that we were in fact innately perfect and that we had to keep coming back again and again to rediscover our true nature. I felt that somehow our perfection had become obscured and that we had to uncover it, to find out who we really were. And that was what we were here for.

'Our mind is so untamed, out of control, constantly creating memories, prejudices, mental commentaries. It's like a riot act for most people! Anarchy within. We have no way of choosing how to think and the emotions engulf us. Meditation is where you begin to calm the storm, to cease the never-ending chattering of the mind. Once that is achieved you can access the deeper levels of consciousness which exist beyond the surface noise. Along with that comes the gradual disidentification with our thoughts and emotions. You see their transparent nature and no longer totally believe in them. This

...more

'Later people would ask me if I wasn't lonely in my cave. I never was. It was in the monastery where I was really alone,' she said.

'One evening I looked inside and saw this grasping and attachment and how much suffering it was causing me. Seeing it so nakedly at that moment it all fell away.

Tenzin Palmo had hit the spiritual glass ceiling - the one which all Buddhist nuns with spiritual aspirations crashed into. Over the centuries they had had a raw deal. While their male counterparts sported in the monastic universities, engrossed in profound scholarship and brilliant dialectical debate, the Tibetan nuns were relegated to small nunneries where, unable to read or write, they were reduced to doing simple rituals, saying prayers for the local community or, worse still, working in monastery kitchens serving the monks. This was why there were no female Dalai Lamas, no female lineage

...more

Their sisters in the southern schools of Buddhism had it worse. In Thailand the nuns had to shuffle backwards on their knees away from any monk and never allow any part of their body to touch his meditation mat. Those with big breasts were ordered to bind them up so as not to appear overtly female!

In Tibet, where the word for woman is 'inferior born', it was written that 'on the basis of her body' a woman was lesser than a man. Consequently at any religious ceremony the nuns had to sit behind the monks, and in the offering of the butter tea the most senior nun would be served after a monk of one day's ordination.

'The Buddha was truly Enlightened and saw things as they really were. Others, however, used the Buddha's insights to serve their own purposes.

"Usha"was the honorific name for "hat" and that the Karmapa was going to perform the black hat ceremony.' Tenzin Palmo was about to be privy to one of the most mystic and powerful rituals that existed in Tibetan Buddhism. Said to be made from the hair of 100,000 Dakinis (powerful female spirits), the black hat or crown was regarded as a mystic object of awesome power. It was believed to be self-existent over the head of all the Karmapas, visible to those whose sight was pure enough to see it, and was held to be capable of liberating on sight.

Out of all the monks, the Togdens alone treated Tenzin Palmo as one of their own.

'The amazing thing about these yogis is that they are so ordinary,' Tenzin Palmo continued. 'There's no ego there. They are wonderful people, totally unjudgemental, totally unpretentious, absolutely un-self-regarding and the easiest people in the world to be with. Their minds are so vast.

One day Tenzin Palmo heard of Togdenmas, the women equivalent of the Togdens, and her heart rose.

The Togdens said that if I had seen the Togdenmas I wouldn't even look at them,' Tenzin Palmo said. 'I knew that was what I wanted to be. I rushed to Khamtrul Rinpoche to ask him. He was delighted. "In Tibet I had many Togdenmas," he said, "but now I don't have even one. I pray that you will become an instrument in re-establishing the Togdenma lineage."'

'When I counted up how long it lasted it was forty-nine days, which was interesting because that is said to be the duration of the Bardo, the period of transition between death and rebirth. In fact it was really like a kind of Bardo, I was having to wait. Then it gradually got a little better. What I learnt from that was that the exhaustion that pain brings arises because we resist it. The thing is to learn to go with the pain, to ride it.'

To those who looked on, it was proof that Khamtrul Rinpoche had indeed reached a high level of spiritual attainment, one only surpassed by the ultimate triumph of achieving the 'rainbow body' whereby at death the whole body is de-materialized, leaving nothing behind but the nails and hair. Such things could well be dismissed as spiritual science fiction were it not for the plethora of eye-witnesses and factual documentation to back them up.

Rilbur Rinpoche, a venerable high lama and historian who was imprisoned for many years by the Chinese, tells of several adepts who managed to eject their consciousness at will (the practice of powa) while imprisoned with him. 'I saw many people who sat down in the corner of their cell and deliberately passed away to another realm. They weren't ill and there was nothing wrong with them. The guards could never believe it!' he said.

Khamtrul Rinpoche's remains were duly placed in the stupa that had been erected next to the very temple that he had designed and helped to build with his own hands. It was a tall, impressive structure, gleaming white, built according to the laws of sacred geometry and containing a small glass window behind which sat a statue of the Buddha. Strangely a bodhi seed implanted itself behind the glass and over the years a bodhi tree forced its way out of the very centre of the container. It had grown from the heart of the Buddha. No one knew how it had got there, nor how it had grown without any

...more

'I felt that the only thing that I could really do to repay my kind lama was practise, practise, practise,' she said.

A realization is the white transparent light at the centre of the prism, not the rainbow colours around it.'

'The only problem with bliss is that because it arouses such enormous pleasure, beyond anything on a worldly level, including sexual bliss, people cling to it and really want it and then it becomes another obstacle,'

The Togdens turned to me and said, "You know, when you start, this is what happens. You get completely overwhelmed by bliss and you don't know what to do. After a while you learn how to control it and bring it down to manageable levels." And it's true.

'You see, bliss in itself is useless,' she continued. 'It's only useful when it is used as a state of mind for understanding Emptiness - when that blissful mind is able to look into its own nature. Otherwise it is just another subject of Samsara.

The blissful mind is a very subtle mind and that kind of mind looking at Emptiness is a very different thing from the gross mind looking at emptiness. And that is why one cultivates bliss.

'You go through bliss. It marks just a stage on the journey. The ultimate goal is to realize the nature of the mind,' she insisted. The nature of the mind, she said, was unconditioned, non-dual consciousness. It was Emptiness and bliss. It was the state of Knowing without the Knower.

Suddenly the Buddha's First Noble Truth which she had learnt when she first encountered Buddhism struck her with renewed force. 'I thought, "Why are you still looking for happiness in Samsara? and my mind just changed around. It was like: That's right- Samsara is Dukka [the fundamental unsatisfactory nature of life].

It's OK that it's snowing. It's OK that I'm sick because that is the nature of Samsara. There's nothing to worry about. If it goes well that's nice. If it doesn't go well that's also nice. It doesn't make any difference.

It was Tara they turned to in their moments of greatest distress because Tara, as a woman, heard and acted quickly. She was compassion in action, said to have been born out of the tears of the male Buddha Chenrezig, who saw the suffering of all sentient beings but was unable to do anything about it. Tara, it was said, had the distinction of being the first woman to attain Enlightenment.

She would do away with the traditional system of individual sponsorship, which had been in place for centuries in Tibet, whereby monks and nuns got the money needed for their keep from family members or wealthy patrons. This, she pointed out, was an invidious practice as it not only created competition and cunning (as the monastics vied to see who got more), but produced a mundane, worldly mind-frame which took the focus away from the spiritual life.

'Our minds are like junk yards. What we put into them is mostly rubbish! The conversations, the newspapers, the entertainment, we just pile it all in. There's a jam session going on in there. And the problem is it makes us very tired,'

'When we normally think of resting we switch on the TV, or go out, or have a drink. But that does not give us real rest. It's just putting more stuff in. Even sleep is not true rest for the mind. To get genuine relaxation we need to give ourselves some inner space. We need to clear out the junk yard, quieten the inner noise. And the way to do that is to keep the mind in the moment. That's the most perfect rest for the mind. That's meditation. Awareness. The mind relaxed and alert. Five minutes of that and you'll feel refreshed, and wide awake,'

'Meditation is not just about sitting in a cave for twelve years,' she pronounces. 'It's everyday life. Where else do you practise generosity, patience, ethics?

'The film Ground Hog Day was a very Buddhist movie,' she says. 'It was about a man who had to live the same day over and over again. He couldn't prevent the events occurring, but he did learn that how he responded to them transformed the whole experience of the day. He discovered that as his mind began to get over its animosity and greed and as he started to think of others his life improved greatly.

'And that was the Buddha's great understanding - to realize that the further back we go the more open and empty the quality of our consciousness becomes. Instead of finding some solid little eternal entity, which is "I", we get back to this vast spacious mind which is interconnected with all living beings. In this space you have to ask, where is the "I", and where is the "other". As long as we are in the realm of duality, there is "I" and "other". This is our basic delusion - it's what causes all our problems,'

Ignorance, according to Buddhism, is not ignorance about this or that on an intellectual level - it's ignorance in the sense of unknowing. We create this sense of an "I" and everything else which is "Non I". And from that comes this attraction to other "Non I's" which "I" want, and this aversion to everything I don't want. This is the source of our greed, our aversion and all the other negative qualities which we have. It all comes from this basic dual misapprehension.

Buddhist centres, specifically Tibetan Buddhist, had mushroomed all over the globe. But now the honeymoon was over. The early disciples, after thirty years of investigation and practice, began to see a more realistic - and human - face of the religion which had been transplanted into their soil. Flaws emerged, discrepancies arose and while Eastern mores may have forbidden outright criticism of its established religion and spiritual figureheads, the West, with its right of free speech, had no such scruples.

The Dalai Lama had his own recipe for distinguishing between an authentic guru and a fake: 'You should "spy" on him or her for at least ten years. You should listen, examine, watch, until you are convinced that the person is sincere. In the meantime you should treat him or her as an ordinary human being and receiving their teaching as "just information". In the end the authority of a guru is bestowed by the disciple. The guru doesn't go out looking for students. It is the student who has to ask the guru to teach and guide,' he said.

there's a great little practice called the half-smile where you slightly lift the corners of your mouth and hold it for three breaths. If I do it six or more times a day within three days it makes a surprising difference to the body and mind. You can do it during any time of waiting, when you're kept on hold on the telephone, at the grocery store, in the airport at the stop lights,'

'Besides, I've discovered that if I try to push things the way I think they should be done everything goes wrong.'

In 1995 a German nun called Edith Besch refound the spot made famous by Tenzin Palmo and built the cave up again - on a much grander scale. A room was added and the front wall built out. There was even a separate kitchen and an outside toilet. Edith only managed one year in the cave, however, before being taken ill with cancer and dying in a monastery in the valley below, aged just forty-three. The local people attested that she had been notoriously hot-tempered when she arrived, but after twelve months of retreat had emerged serene and patient in spite of her sickness and had died a peaceful

...more