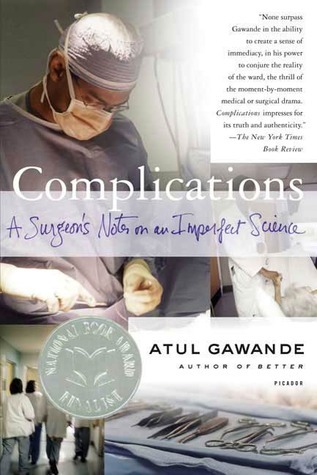

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Atul Gawande

Read between

May 9 - June 9, 2018

We look for medicine to be an orderly field of knowledge and procedure. But it is not. It is an imperfect science, an enterprise of constantly changing knowledge, uncertain information, fallible individuals, and at the same time lives on the line. There is science in what we do, yes, but also habit, intuition, and sometimes plain old guessing. The gap between what we know and what we aim for persists. And this gap complicates everything we do.

Her gratitude was immense and flattering, like the lion’s for the mouse—and that night I went home elated.

Skill, surgeons believe, can be taught; tenacity cannot.

Maybe machines can decide, but we still need doctors to heal.

The important question isn’t how to keep bad physicians from harming patients; it’s how to keep good physicians from harming patients.

“If you’re not a little afraid when you operate,” he said, “you’re bound to do a patient a grave disservice.”

The doctor is often only the final actor in a chain of events that set him or her up to fail.

No matter what measures are taken, doctors will sometimes falter, and it isn’t reasonable to ask that we achieve perfection. What is reasonable is to ask that we never cease to aim for it.

Medicine requires the fortitude to take what comes: your schedule may be packed, the hour late, your child waiting for you to pick him up after swimming practice; but if a problem arises you have to do what is necessary.

Medicine’s ground state is uncertainty. And wisdom—for both patients and doctors—is defined by how one copes with it.

What we are drawn to in this imperfect science, what we in fact covet in our way, is the alterable moment—the fragile but crystalline opportunity for one’s know-how, ability, or just gut instinct to change the course of another’s life for the better.