More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

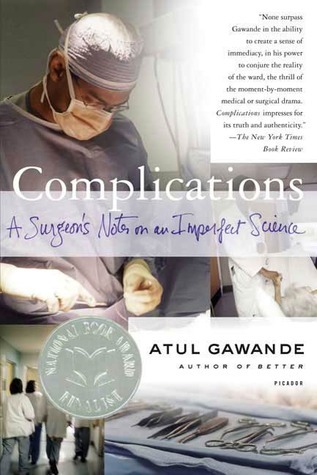

by

Atul Gawande

Read between

May 25 - June 16, 2018

This is the uncomfortable truth about teaching. By traditional ethics and public insistence (not to mention court rulings), a patient’s right to the best care possible must trump the objective of training novices. We want perfection without practice. Yet everyone is harmed if no one is trained for the future.

Petra X and 2 other people liked this

I asked Byrnes Shouldice, a son of the clinic’s founder and a hernia surgeon himself, whether he ever got bored doing hernias all day long. “No,” he said in a Spock-like voice. “Perfection is the excitement.”

To much of the public—and certainly to lawyers and the media—medical error is fundamentally a problem of bad doctors. The way that things go wrong in medicine is normally unseen and, consequently, often misunderstood. Mistakes do happen. We tend to think of them as aberrant. They are, however, anything but.

It was estimated that, nationwide, upward of forty-four thousand patients die each year at least partly as a result of errors in care.

No matter what measures are taken, doctors will sometimes falter, and it isn’t reasonable to ask that we achieve perfection. What is reasonable is to ask that we never cease to aim for it.

What he found was unsurprising. The doctors were often not recognized to be dangerous until they had done considerable damage.

Chronic back pain is now second only to the common cold as a cause of lost work time, and it accounts for some 40 percent of workers’ compensation payments.