More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In the latter half of the 1990s, telecom companies in the U.S. laid enough new fiber-optic cable to spark a 50 percent increase in total route miles—and a thousand-fold increase in bandwidth, thanks to miraculous advances in the underlying technology. Yet demand rose only a hundred-fold in this time, creating an imbalance that led, inevitably, to a crushing shakeout: $1 trillion in lost stock-market value, $275 billion in defaulted debt, 225,000 axed jobs, dozens of dead companies and a handful of breathtakingly large bankruptcies.

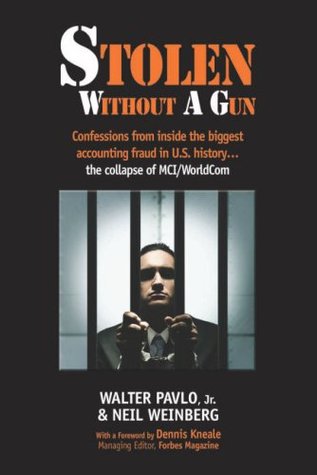

Bernard J. Ebbers, founder of the moxie-fueled telco MCI WorldCom, oversaw, with temerity and impunity, the falsification of $11 billion in profits, a new record high in the annals of fraud. Such large-scale schemes, however, are an outgrowth of complicity and cooperation below, among dozens of smaller parts and bit players.

In alternately gripping and fascinating detail, we watch Pavlo go from hopeful wunderkind to cynic to multimillion-dollar thief, at a time when it seemed like everyone was in on it—reseller scammers that ran up big bills owed to MCI and other majors; international-calling schemes; 900 numbers for phone sex and astrology readings; salesmen signing up unreliable carriers to spark bigger bonuses; and their bosses ignoring the abuses and benefiting from same.

In the fraud triangle of rationalization (I'm underpaid, everyone's cheating), opportunity (lax controls) and pressure (I gotta make my numbers), chicanery and flimflam fourish.

Within months of the story's publication, his tale of the accounting fraud he took part in helped drive WorldCom, and the former MCI with it, into the largest bankruptcy in history. Altogether, an estimated $2 trillion in shareholder value was squandered in the technology and telecom implosions.

Inmates in the federal system are usually assigned to minimum security camps because they've pleaded guilty, have short sentences or are nearing the end of long ones, and are not violent. The Jesup camp was the same place Praise The Lord Club founder Jim Bakker had been locked up for fraud.

Camp time was the easiest a con could do, so nobody wanted to screw up. But occasionally some miscreant figured out a way to get more time than he already had. One obese, middle-aged embezzler had slunk off to the woods one night for an unapproved conjugal visit with his wife.

Pavlo would have preferred to stay at Jesup, but he was eager to take advantage of a prison alcoholic treatment program available at Edgefield. If he completed it, he could shave twenty-four months off his sentence.

Pavlo had heard stories of prisoners getting lost in the Con Air system for months, rotting in holding cells after being misdirected like lost mail to the wrong facilities and thrown into segregation while the Bureau of Prisons took its time sorting out the paperwork. Once you were on a prison bus, the legend went, only God knew where you'd end up. If you were lucky, you'd go straight from point “A” to point “B.” If you weren't, you might find yourself touring the far-flung outposts of the federal prison system.

Sometimes the extra mileage was deliberate. Cons who refused to cooperate with investigators and testify against others, or filed too many nuisance lawsuits against the Bureau of Prisons, or caused some other trouble, were tagged for “diesel therapy,” the torture of endless bus rides and prison holding cells.

Diesel therapy was a way of making inmates disappear. No one outside the system knew where these men were. What mattered was they couldn't cause any trouble, and had lots of time to contemplate whether they might be willing to become state's witnesses or otherwise modify their behavior.

In the business world Pavlo had left behind, his youthful good looks and blond hair had given him an edge. In prison, it made him feel like a three-legged deer listening to the howl of a wolf pack.

Pavlo stumbled, swaying, down the aisle between the men to the back of the bus where the stench was even more intense. The source was a plywood plank in the floor with a hole cut in the middle and human waste sloshing around in a tank below. Right next to the splashing sewage sat a water dispenser, a stack of Dixie cups, and two cardboard boxes of Oscar Mayer Lunchables, the same snacks Pavlo had lovingly packed in his sons' school bags in his old life.

A week after he arrived in Tallahassee, Pavlo was awakened by a guard around 2:00 a.m. He was moved to the processing area, stripped, ordered to lean his hands against the wall and spread his legs for a body search. Then he was told to put on an orange jumpsuit, shackled and left standing around for seven hours before loading onto a bus. No special “awdalee” dispensation this time. He was just another one of the brothers. The white sheep of the family.

Built in 1900, the Big A, as the maximum-security United States Penitentiary in Atlanta was known, looked every inch the hell-hole it was reputed to be. It had housed Al Capone and been spattered with blood during the 1987 Cuban prison riots. An inner graveyard held unclaimed residents.

William McGowan had bought into Microwave Communications of America, as MCI was originally known, in 1968 with a vision to use the fledgling provider of two-way truck radios to build a nationwide long-distance telephone company.

McGowan, a Harvard MBA, set up shop at 1801 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. and created what by his own account was “a law firm with an antenna on the roof.”

The venture was so dicey, and MCI came so close to bankruptcy, that on one occasion even its copy machines were repossessed. In the end, McGowan won the battle in the court room, convincing Judge Harold Greene that AT&T no longer deserved special treatment and protection as a public utility.

McGowan went down in history as the David who brought down the telecommunications Goliath when Ma Bell was broken up in 1984 into a long-distance company, AT&T, and several regional bells. Then he rode the wave, enjoying his cult status as an innovator and loading MCI up with a mountain of debt, courtesy of junk-bond king Michael Milken.

Salesmanship coursed through McGowan's veins. Early in his career, before MCI caught his eye, he was pitching shark repellent to the Navy to protect downed pilots when his product began attracting the beasts. Without missing a beat, he began selling the brass on why the Navy needed a shark aphrodisiac.

MCI helped build long-distance market share with compensation that was sometimes 100 percent commission-driven3 and customer loyalty with clever promotions. One pitched free Mother's Day calls with the tag line “Give mom a priceless ring.”

By 1992, MCI was an established upstart with about 15 percent of the long-distance market and revenues of $11 billion. As Pavlo arrived for work that July, the company's four-month-old “Friends & Family” calling plan was luring half a million households a month from AT&T and Sprint.4 Its stock price had doubled to around $20 in the previous two years, outdoing even its own 27 percent average return during the 17 years since its original listing.

The only imperfection seemed to be the department that had hired him—Financial Services. Accounts receivable, credit, and collections for the Southeast. He was going to be a bill collector.

He entered the seven-story tropical atrium and took the elevator to MCI's second floor lobby. Next to the reception desk, a ticker flashed the company stock price. A photo of Bill McGowan sat on a table surrounded by flowers. MCI's visionary leader had collapsed and died of a heart attack a month earlier.6

“What, for public consumption, we refer to as our esteemed carrier clientele is actually a snake pit of thieves. The bastards collect money from their own customers, run up big tabs on our network and then head for the door like sorority sisters skipping out on the bar bill. You're gonna love it.

Pavlo found his new office at the end of a maze of desks at which some two dozen clerks sat surrounded by piles of paperwork. In one corner sat a half-dozen shared computers. This looked nothing like the gleaming conference rooms where Pavlo had been interviewed.

This carrier finance stuff is pretty simple. If every one of us big phone companies laid fiber to haul calls to every corner of the country, we'd all be bankrupt and the U.S. would be one big construction trench. So we use the other guys' networks in some places and they use ours in others. Our job is to track what they use and make sure MCI gets paid.”

our Friends & Family commercials aren't going to fill the network so we wholesale to competitors. I know it sounds screwy, but these guys can bring in serious numbers of minutes. The problem is they discount like hell, push down prices and cannibalize our business.”

They game the system too, but it's the three hundred you've never heard of that cause us to shit bricks. Most don't do a damn thing but run traffic over our network and slap their names on bills. The arcades are the worst.” “What're they?” “Telecom's equivalent of crack houses,” McCumber said. “They rent a line in a slum somewhere and charge a bunch of bastards too poor to own phones obscene rates to make calls. Their over-nineties can be killers.” “What's that?” “Debts owed MCI that're over ninety days past due. The way we track debt is current, meaning less than thirty days outstanding.

...more

We're managing about $250 million that these guys owe us at any given time. This year we won't collect ten or fifteen million of it. That's tolerable. My fear is the way Sales is going at some point we'll have so many fly-by-nights on the network the figure will blow sky high. I must've warned management a hundred times.”

“First rule of Carrier Finance. Never believe a word a carrier tells you. The second rule is never believe a syllable that comes out the puke-hole of an MCI Sales rep.”

Turnover in Sales is huge. Chasing down the lowlifes they sign up is our problem. Welcome to Carrier Finance.”

THE FIRST TIME he heard the word “audiotext,” Pavlo thought it sounded like the term to describe a radio script for a show like A Prairie Home Companion. Instead, it was the euphemism in the phone business for the burgeoning traffic in phone sex, astrology, racing results, for-profit evangelism, personals, and sports scores.

Audiotext began to boom in the 1980s, but it actually got its start in 1927 when New Jersey Bell first offered callers the exact time of day. In the beginning, live operators—always women—answered the phones and announced the time. But sex was on the minds of many male callers, so the company instructed its operators to mimic the recorded messages that were just coming on the scene, so they wouldn't spend their shifts fending off propositions.

AT&T offered the first long-distance audiotext service in the early 1980s to poll TV viewers, using the 900 prefix to distinguish it from toll-free 800 service. Callers paid fifty cents each to vote on everything from who won the Reagan-Carter debate to whether Saturday Night Live's Eddie Murphy should boil Larry the Lobster.

In 1988, 900 audiotext calls generated an estimated $2.5 billion in revenue.2 Even President George H.W. Bush got in the act, appearing in an ad urging viewers to call a 900 number to make contributions to the USO.

AT&T went so far as to open an office in Chicago and staff it with employees assigned to leaf through skin magazines looking for dial-a-porn ads, then check whether they matched any of the numbers it rented out.

Mann had gotten his start in telecom working for a Toronto phone-sex company called Denmark Dial.

Mann fancied himself the architect of a vast, vertically integrated pornography empire that one day would turn him into an industry icon, like Hugh Hefner or, better yet, Larry Flynt.

“You know how AT&T tells callers to 'Reach out and touch someone'?” Nobody ever called Pavlo “Wally.” “Yeah.” “What does MCI tell them to do?” “Reach out and touch someone for less.” “Bingo. And my company?” Mann asked “I haven't got any idea.” “Reach out and touch yourself!' Pretty snappy, eh?” “Brilliant.”

Here was the secret of MCI's most profitable business, lonely men dialing numbers like 1-900-GET-SOME for a few minutes of imagined pleasure.

The way it worked was the call was picked up by the regional Bell company switching station which recognized it by a Carrier Identification Code, or CIC, assigned to MCI, in this case 022. The call was then routed over MCI's network to one of its 50 or so 900-line clients. The law required that the caller be forewarned that there would be a per-minute charge, usually two-to-five dollars a minute. Then the call was routed to a “phone mate.” The average caller would have his “needs” fulfilled in about eight minutes, generating a charge on his next phone bill of perhaps $24.

When Mr. Lonelyheart paid his Bell company bill, the local phone company got to keep a dollar for its trouble, passing on the rest to MCI, which charged 15 cents a minute for long-distance service and another $2 or so for billing and collections. That left companies like Mann's TPC between $15 and $20 a call to cover Bambi, office rent, and Mann's high life.

The problem for many of these 900-call startups was that it took the Bell companies ninety days or more to fork over their share. Many a porn kingpin had...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Mann had figured out how to reverse the food chain so he got paid first. He did it by turning to the independent financing companies that had started springing up to cut into the big long-distance carriers' lucrative billing and collections businesses. The lenders enabled Mann to “factor” some of the money he was due. That meant an outside lender known as a factor would calculate how much TPC was owed by its callers and lend it 80 percent or so of those so-called receivables. When the cash eventually rol...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By the time Pavlo showed up in 1992, Mann's revenues were running about $5 million a month on long-distance calls that cost him $600,000 to deliver over MCI's network. Pavlo figured that even after paying his phone mates and other overhead, Mann had to be clearing $20 million a year.

When Mann started financing his receivables elsewhere, he stopped paying MCI on time. Pavlo's mission that day was to find a solution.

“What? He's gonna cut me off?” Mann asked, feigning concern by clutching his chest with his hand. “That would force me to switch carriers and take at least a phone call.” “You signed a contract.” “So sue me. You can take a number and get in line. TPC doesn't have any assets. If it fies, fucks or floats, I lease it.”