More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Lucy Moore

Read between

September 20 - October 21, 2020

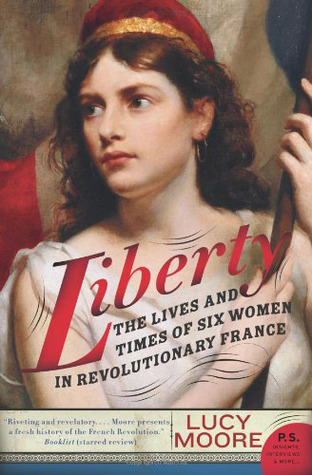

Thérésia de Fontenay.

‘The Revolution must be attributed to every thing, and to nothing,’ wrote Germaine. ‘Every year of the century led toward it by every path.’

In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman written in 1792 Mary Wollstonecraft declared that stiff, uncomfortable clothes, like the ‘fiction’ of beauty itself, were a means by which society kept women submissive and dependent.

Conversation, she said, was a certain way in which people act upon one another, a quick give-and-take of pleasure, a way of speaking as soon as one thinks, of rejoicing in oneself in the immediate present, of being applauded without making an effort, of displaying one’s intelligence by every nuance of intonation, gesture and look–in short, the ability to produce at will a kind of electricity.

her husband, whom she charitably described as being, ‘of all the men I could never love…the one I like best’.

Instead of playing, she watched Diderot, Gibbon, Voltaire, Grimm and Buffon spar in her mother’s Friday salons; she did not have a friend her own age until she was twelve.

he observes that in robbing women of their myth by speaking of their “rights rather than their reign”, he may fail to earn their approval, for he saw all about him the stampede among women to Rousseauist views’, which granted them dominion over men’s hearts but no political rights.

Germaine thought England had ‘attained the perfection of the social order’, with its division of power between Crown, aristocracy and people.

Robespierre was a prominent member of a club formed at Versailles in the summer of 1789 by a group of progressive deputies with the purpose of debating issues before they came before the National Assembly. The Society of the Friends of the Constitution would become known as the Jacobin Club because, when the Assembly moved to Paris that October, they hired the hall of a Dominican (Jacobin, in French slang)

the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen which established in its first article that all men are born and live free and equal. Torture and arbitrary imprisonment were abolished and innocence was presumed; freedom of the press and of worship was declared; citizens were to bear the weight of taxation according to their abilities; the army was defined as a public force and access to the officers’ ranks opened up to non-nobles.

‘We suffer more than men who with their declarations of rights leave us in the state of inferiority and, let’s be truthful, of slavery in which they’ve kept us so long,’

All over France, common women gathered together in clubs of different types to demonstrate their patriotism and their devotion to the revolution. Some dared call for girls to be better educated; others demanded the privilege of fighting for the patrie, or rights of consent over marriage and inheritance.

Pauline Léon presented to the National Assembly a petition bearing over three hundred signatures. In the event of a foreign war, she argued, women would be left defenceless at home; they needed weapons in order to defend the patrie from its hidden, internal enemies.

Théroigne was described again and again by nineteenth-century historians of the revolution as having been at the vanguard of the mob storming the palace, astride a jet-black charger and dressed in a riding-habit ‘the colour of blood’, with her sabre unsheathed

For women, the revolution’s rejection of the paternal authority of the ancien régime state carried within it an implicit rejection of the private injustices they endured in their own lives.

‘During this moment of upheaval, the rich mixed with the poor and did not disdain to speak to them as equals.’

It was not just the poor who were counted as passive citizens: even if they paid taxes, women, blacks, non-Catholics, domestic servants and actors were all forbidden the vote and considered incapable of participating in public life.

Lace-makers rioted in Normandy and Velay in 1793; Lyon, centre of the textile industry, was defiantly anti-revolutionary.

It was becoming clear to her that her fellow-revolutionaries were campaigning for the rights of men, not the rights of humanity; her struggle was unimportant to them.

Thérésia, still a child, was ‘prostituted’ to an infamous rake.

Many husbands encouraged their brides to take lovers, aware that if their wives were busy elsewhere their own activities would escape attention.

Mme de la Tour du Pin compared her to the goddess Diana – though no doubt in her aspect as huntress rather than virgin – enthusing that ‘no more beautiful creature had ever come from the hands of the Creator’. Thérésia’s statuesque looks were enhanced by ‘matchless grace’, ‘radiant femininity’ and a peculiarly charming voice ‘of caressing magic’, husky, melodious and slightly accented.

In Paris, meanwhile, rapturous preparations for the anniversary of the Bastille’s fall were under way, as men and women of all ages and classes, ‘inspired by the same spirit’, helped turn the Champs de Mars into a vast amphitheatre. Even the king took his turn with a spade.

‘I have found out that an aristocrate always begins a political conversation assuring you he is not one – that no one wished more sincerely than him for reform,’ she wrote in 1794. They would continue, she said, by protesting, ‘But to take away the King’s power, to deprive the clergy of their revenues, is pushing things to an extremity,

Brissot’s Travels in the United States was intended to hold up the American example as a model to Frenchmen. He called Americans ‘the true heroes of humanity’ because they had discovered the secret of preserving individual liberty by correlating their private morality with their public responsibility.

‘If souls were pre-existent to bodies and permitted to choose those they would inhabit,’ she told a friend in 1768, ‘I assure you that mine would not have adopted a weak and inept sex which often remains useless.’

Manon accepted unquestioningly his belief that women should never venture outside domestic life. She would have agreed with the words of Germaine de Staël, another devotee of Rousseau’s: ‘it is right to exclude women from public affairs. Nothing is more opposed to their natural vocation than a relationship of rivalry with men, and personal celebrity will always bring the ruin of their happiness.’

As she wrote to Roland before their marriage, when she read a novel, she never played the secondary role: ‘I have not read of a single act of courage or virtue without daring to believe myself capable of performing it myself.’

Determined to find happiness in her domestic life even if it did not include romantic love or physical satisfaction, the young Mme Roland threw herself into her relationship with the husband she thought of as having ‘no sex’. She honoured and cherished him ‘as an affectionate daughter loves a virtuous father’

Like many men and women of their background who saw themselves as excluded from influence and privilege simply by virtue of their birth, and who chafed against the inequalities of the old system, during the 1780s the Rolands considered emigrating to the United States.

American crown was seen as surpassing the virtuous republicanism even of the Greeks and Romans.

Abigail Adams’s vain plea to her husband John: I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands [she wrote in 1776]. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to ferment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have not voice or Representation.

As Simon Schama writes, violence ‘was not just an unfortunate side effect’ of the revolution, but its ‘source of collective energy. It was what made the Revolution revolutionary.’ Manon Roland was as aware of this brutal truth as was Marat himself.

Lafayette, who had persuaded the mayor to declare martial law in Paris, ordered the National Guard to open fire on the demonstrators. Perhaps fifty people were killed.

Louis XVI signed the constitution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen on 30 September 1791, while the Rolands were away from Paris. It created a constitutional monarchy in which only propertied men were active citizens. All women were passive citizens, although the laws governing marriage, divorce and inheritance were made fairer; early proposals to allow wives property rights equal to their husbands’ had been rejected outright.

‘Women are now respected and excluded,’ she wrote; ‘under the old regime they were despised and powerful.’ The first article stated unequivocally, ‘Woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights.’ Gouges demanded that women share with men both the burdens and the privileges of public services, taxation and representation. ‘Woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum,’ she wrote.

Although Manon was obliged to give twice-weekly dinners for her husband’s colleagues and associates, still she invited no women, served her guests only one simple course and provided them with sugar-water rather than wine. She was determined that her behaviour should set the tone for a new republic of virtue.

Théroigne replied that she had heard of a vault in Rome bearing a statue of a Fury with a dagger: This vision came to me because, having always been offended by the tyranny which men exercise over my own sex, I wished to find an emblem for it in this picture, in which the death of this tyranny would mark the downfall of the prejudices under which we groan, and which it was my dearest wish to have been able to destroy.

She also recommended the formation of regiments of female soldiers–not a home guard of women to defend the patrie against internal enemies of the revolution, like that for which Pauline Léon petitioned, but actual fighters, amazones, in the field of battle.

On 29 May the king agreed that his personal bodyguard, a privilege granted to him as a safeguard of his constitutional role, be disbanded, amid worries that it would rise to join an invading Austrian force.

‘War Song for the Army of the Rhine’, which would become known as the ‘Marseillaise’.

Lafayette (dismissed from his post at this time, he crossed enemy lines and spent the rest of the revolution in an Austrian prison)–

Although they had not been permitted to share the same civic rights and freedoms as men, from September 1792 women would be held accountable for their perceived crimes. It was equality of the the most unjust nature.

The metric system was introduced. Gilbert Romme, Théroigne de Méricourt’s partner in the short-lived Society of the Friends of the Law, would be one of the chief architects of the new revolutionary calendar, in which the first day of the first year was 23 September 1792. As Tom Paine had said of the American Revolution, it was indeed a new dawn.

Divorce was also made legal. Over three thousand couples in Paris alone took advantage of this new liberty in its first year.

Perhaps twenty-five thousand French men and women were living in exile in England by 1794; after the revolutionary government passed a law confiscating the property of all émigrés, almost all of them were impoverished. Germaine was an exception because her assets were held abroad and because her husband’s status conferred diplomatic immunity on her.

the Girondins believed the revolution was achieved, whereas the Montagnards wanted to push it still further.

One of the obvious differences between the Montagnards and the Girondins in the first weeks of the National Convention was that while the Montagnards were content to draw a veil over the events of early September, the Girondins wanted to bring the perpetrators to justice–

Robespierre counterattacked by turning Louvet’s criticisms on their head. He managed to make his obsessive personal identification with the popular will a virtue rather than a fault–he was simply the agent of France’s destiny–and defended the recent surge of violence by explaining that the revolution required it and must not be judged by ordinary standards of morality. ‘Do you want a Revolution without a revolution?’ he asked dramatically.

Mary Wollstonecraft watched Louis’s carriage pass by her window on his way to the guillotine,