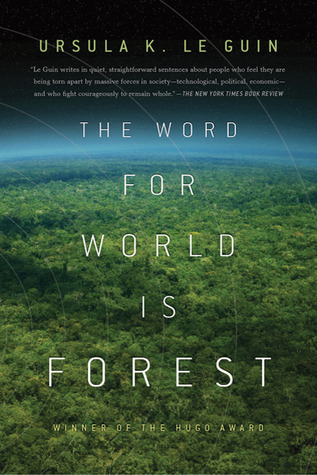

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 7 - December 8, 2024

“The world is always new,” said Coro Mena, “however old its roots.

There is a wish to kill in them, and therefore I saw fit to put them to death.”

“And all men’s dreams,” said Coro Mena, cross-legged in shadow, “will be changed. They will never be the same again. I shall never walk again that path I came with you yesterday, the way up from the willow grove that I’ve walked on all my life. It is changed. You have walked on it and it is utterly changed. Before this day the thing we had to do was the right thing to do; the way we had to go was the right way and led us home. Where is our home now?

Lyubov, who taught me, understood me when I showed him how to dream, and yet even so he called the world-time ‘real’ and the dream-time ‘unreal,’ as if that were the difference between them.”

I’m as full of forebodings as a stupid old man, I must dream. . . .”

The Athshean word for world is also the word for forest. I submit, Commander Yung, that though the colony may not be in imminent danger, the planet is—”

The fact is, the only time a man is really and entirely a man is when he’s just had a woman or just killed another man. That wasn’t original, he’d read it in some old books; but it was true. That was why he liked to imagine scenes like that. Even if the creechies weren’t actually men.

Athshe, which meant the Forest, and the World. So Earth, Terra, meant both the soil and the planet, two meanings and one. But to the Athsheans soil, ground, earth was not that to which the dead return and by which the living live: the substance of their world was not earth, but forest. Terran man was clay, red dust. Athshean man was branch and root. They did not carve figures of themselves in stone, only in wood.

“They’re always pawing each other,” some of the colonists sneered, unable to see in these touch-exchanges anything but their own eroticism which, forced to concentrate itself exclusively on sex and then repressed and frustrated, invades and poisons every sensual pleasure, every humane response: the victory of a blinded, furtive Cupid over the great brooding mother of all the seas and stars, all the leaves of trees, all the gestures of men, Venus Genetrix. . . .

He tried to tell himself that Selver had not been rejecting him, Lyubov, but him as a Terran. It made no difference. It never does.

But old women are different from everybody else, they say what they think.

Intellect to the men, politics to the women, and ethics to the interaction of both: that’s their arrangement.

For if it’s all the rest of us who are killed by the suicide, it’s himself whom the murderer kills; only he has to do it over, and over, and over.

“I can’t see why any hilfer voluntarily ties himself up to an Open Colony. You know the people you’re studying are going to get plowed under, and probably wiped out. It’s the way things are. It’s human nature, and you must know you can’t change that. Then why come and watch the process? Masochism?” “I don’t know what ‘human nature’ is. Maybe leaving descriptions of what we wipe out is part of human nature.—Is it much pleasanter for an ecologist, really?”

If a god was a translator, what did he translate?

A link: one who could speak aloud the perceptions of the subconscious. To ‘speak’ that tongue is to act. To do a new thing. To change or to be changed, radically, from the root. For the root is the dream. And the translator is the god. Selver had brought a new word into the language of his people. He had done a new deed. The word, the deed, murder. Only a god could lead so great a newcomer as Death across the bridge between the worlds.

He preferred to be enlightened, rather than to enlighten; to seek facts rather than the Truth. But even the most unmissionary soul, unless he pretend he has no emotions, is sometimes faced with a choice between commission and omission. “What are they doing?” abruptly becomes, “What are we doing?” and then, “What must I do?”

In diversity is life and where there’s life there’s hope, was the general sum of his creed, a modest one to be sure.

Kneeling there in the mud among the dead he thought, This is the dream now, the evil dream. I thought to drive it, but it drives me.

They were more protective of their machines than of their bodies.

None of them said anything. They looked down at him. Seven big men, with tan or brown hairless skin, cloth-covered, dark-eyed, grim-faced; twelve small men, green or brownish-green, fur-covered, with the large eyes of the seminocturnal creature, with dreamy faces; between the two groups, Selver, the translator, frail, disfigured, holding all their destinies in his empty hands. Rain fell softly on the brown earth about them.

“Sometimes a god comes,” Selver said. “He brings a new way to do a thing, or a new thing to be done. A new kind of singing, or a new kind of death. He brings this across the bridge between the dream-time and the world-time. When he has done this, it is done. You cannot take things that exist in the world and try to drive them back into the dream, to hold them inside the dream with walls and pretenses. That is insanity. What is, is. There is no use pretending, now, that we do not know how to kill one another.”

Maybe after I die people will be as they were before I was born, and before you came. But I do not think they will.”