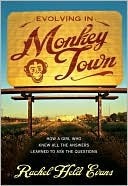

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 13 - November 20, 2013

N. T. Wright made me wonder if perhaps I’d missed the point. Perhaps being a Christian isn’t about experiencing the kingdom of heaven someday but about experiencing the kingdom of heaven every day. Perhaps I could get a little taste of what the Old Testament saints thought was worth sticking around for.

When we live like Jesus, when we take his teachings seriously and apply them to life, we don’t have to wait until we die to experience freedom from sin.

That’s when I realize that if anyone’s an oxymoron, it’s me. Or maybe it’s anyone who claims to follow Jesus.

For as long as I can remember, the Bible has been compared to a weapon, and for as long as I can remember, it has been used as one. Many of us who participated in sword drills as kids never really grew out of them.

The Bible has been, and probably always will be, a relentless, magnetic force that both drives me away from my faith and continuously calls me home. Nothing makes me crazier or gives me more hope than the eclectic collection of sixty-six books that begins with Genesis and finishes with Revelation. It’s difficult to read a word of it without being changed.

All my life I’ve been taught that the Bible is the glue that holds Christianity together, so whenever I encounter parts of it that don’t make sense, I start to worry that my faith might fall apart.

If I’ve learned anything about what it’s like to be on the outside of Christianity looking in, it’s how awful it feels when your questions aren’t taken seriously. Sometimes I just want to hear someone say, “You know, I’m not sure what to make of that either.”

fact, I’d say that how I interpret the Bible (or how I “pick and choose”) says as much about me as it says about God.

Maybe he let David talk about murdering his enemies and Jesus talk about loving his enemies because he didn’t want to spell it out for us. He wanted us to make the right decisions as we went along, together. Maybe God wants us to have these discussions because faith isn’t just about being right; it’s about being a part of a community.

My interpretation can be only as inerrant as I am, and that’s good to keep in mind.

But it seems to me that if evangelical Christians were the only ones to have God all figured out, then they would be the kindest, most generous people around. No offense to you, but in my twenty-plus years in this business, I haven’t found that to be true. Most Christians I know are only interested in winning arguments, converts, and elections.”

Somewhere along the way, the gospel had gotten buried under a massive pile of extras: political positions, lifestyle requirements, and unspoken rules that for whatever reason came with the Christian territory. Sometimes Jesus himself seemed buried beneath the rubble.

They weren’t searching for historical evidence in support of the bodily resurrection of Jesus. They were searching for some signs of life among his followers.

Not once after graduating from Bryan was I asked to make a case for the scientific feasibility of miracles, but often I was asked why Christians aren’t more like Jesus. I

I found that most of the time it wasn’t the weight of the questions themselves that burdened their faith but rather the notion that they shouldn’t be asking them, that it wasn’t allowed.

When the gospel gets all entangled with extras, dangerous ultimatums threaten to take it down with them.

Taking on the yoke of Jesus is not about signing a doctrinal statement or making an intellectual commitment to a set of propositions. It isn’t about being right or getting our facts straight. It is about loving God and loving other people.

Love is bigger than faith, and it’s bigger than works, for it inhabits and transcends both.

So ready with the answers, we didn’t know what the questions were anymore. So prepared to defend the faith, we missed the thrill of discovering it for ourselves. So convinced we had God right, it never occurred to us that we might be wrong.

Doubt is a difficult animal to master because it requires that we learn the difference between doubting God and doubting what we believe about God.

Where would we be if the apostle Peter had not doubted the necessity of food laws, or if Martin Luther had not doubted the notion that salvation can be purchased?

faith is not about defending conquered ground but about discovering new territory. Faith isn’t about being right, or settling down, or refusing to change. Faith is a journey, and every generation contributes its own sketches to the map.

In reaction to very loud atheists like Richard Dawkins, we have become a bit too loud ourselves. Faith in Jesus has been recast as a position in a debate, not a way of life.

My hope is that if I am patient, the questions themselves will dissolve into meaning, the answers won’t matter so much anymore, and perhaps it will all make sense to me on some distant, ordinary day.

If there’s one thing I know for sure, it’s that serious doubt—the kind that leads to despair—begins not when we start asking God questions but when, out of fear, we stop.