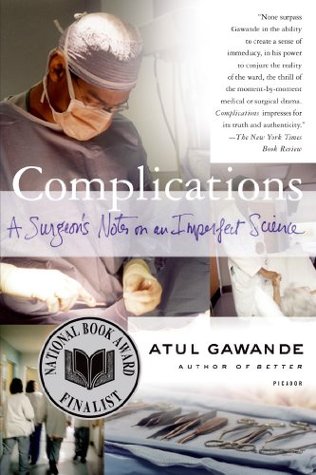

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

By traditional ethics and public insistence (not to mention court rulings), a patient’s right to the best care possible must trump the objective of training novices. We want perfection without practice. Yet everyone is harmed if no one is trained for the future.

As a medical student, the fine balance between practicing on patients and being a good healthcare provider is a fine line to walk. One would either veer too closely to one or the other. Some students may be too callous in their approach, thinking that they can do everything and must learn everything, and not know when they have veered wildly into territory which they have no business dipping their toes into. Yet others like me will have a hard time learning because I wish not to put the patient through the same physical examinations which cause them pain time and time again, and with the voice in the back of my head wondering if perhaps I might be treating them poorly.

However, the thing which is pushing me out of the rut was a single experience in clinic. I did a poor job of seeing the patient, reasoning to myself that we were severely behind schedule, that the doctor would do a much better job anyways, that I knew nothing about cancer patients, and that I did not have any of the answers that the family might want. I essentially did nothing during my visit with the patient and his family. But presenting to the senior resident prior to presenting to the surgeon, I was metaphorically slapped over the head and chastised - I had done a poor job, and I should be ashamed of it. He told me that yes, I might be slow, uninformative, and essentially useless in that moment to the clinic - but it was my opportunity to learn, because one day, there will be no one else looking over my shoulder. One day, I will have to be the one deciding whether or not this patient should get surgery for their cancer. He said a lot more else besides that, but that statement rung in my ears for the rest of the day - I realized that I had not properly used my time in clinic so far. If the surgeon was really going for efficiency, he would have kicked both the resident and myself out and completed clinic all on his own. But this was an opportunity for the two of us to learn - he seized it, and I had ignorantly brushed it off.

If nothing else, I owe it to my future patients to be as meticulous as possible during my training now - to make as many mistakes learning as possible while someone is still looking over my shoulder. And to suck every clinical experience dry of its learning potentials such that I hopefully can avoid making mistakes in the future as much as possible.

Whatever the limits of the M & M, its fierce ethic of personal responsibility for errors is a formidable virtue. No matter what measures are taken, doctors will sometimes falter, and it isn’t reasonable to ask that we achieve perfection. What is reasonable is to ask that we never cease to aim for it.

This reminds me of a quote from When Breath Becomes Air: "You can't ever reach perfection, but you can believe in an asymptote toward which you are ceaselessly striving." This seems to be a common theme among surgeons, if not among all physicians in general.