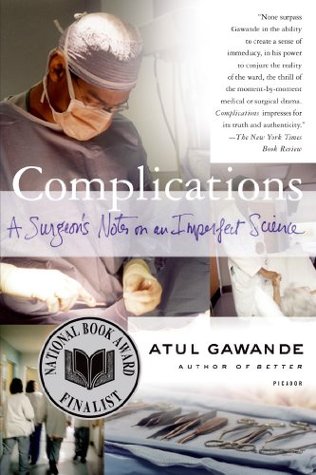

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Atul Gawande

Read between

November 10 - December 31, 2018

Medicine is, I have found, a strange and in many ways disturbing business. The stakes are high, the liberties taken tremendous.

What you find when you get in close, however—close enough to see the furrowed brows, the doubts and missteps, the failures as well as the successes—is how messy, uncertain, and also surprising medicine turns out to be.

We look for medicine to be an orderly field of knowledge and procedure. But it is not. It is an imperfect science, an enterprise of constantly changing knowledge, uncertain information, fallible individuals, and at the same time lives on the line.

As pervasive as medicine has become in modern life, it remains mostly hidden and often misunderstood. We have taken it to be both more perfect than it is and less extraordinary than it can be.

Not everyone appreciates the attractions of surgery. When you are a medical student in the operating room for the first time, and you see the surgeon press the scalpel to someone’s body and open it like fruit, you either shudder in horror or gape in awe.

There is a saying about surgeons, meant as a reproof: “Sometimes wrong; never in doubt.”

Like the tennis player and the oboist and the guy who fixes hard drives, we need practice to get good at what we do. There is one difference in medicine, though: it is people we practice upon.

Surgeons, as a group, adhere to a curious egalitarianism. They believe in practice, not talent.

There have now been many studies of elite performers—international violinists, chess grand masters, professional ice-skaters, mathematicians, and so forth—and the biggest difference researchers find between them and lesser performers is the cumulative amount of deliberate practice they’ve had.

Practice is funny that way. For days and days, you make out only the fragments of what to do. And then one day you’ve got the thing whole. Conscious learning becomes unconscious knowledge, and you cannot say precisely how.

Sick patients can have a certain unmistakable appearance you come to recognize after a while in residency. You may not know exactly what is going on, but you’re sure it’s something worrisome.

In my third year of residency, another friend, the New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell, introduced me to his editor Henry Finder. And for this I consider myself one of the luckiest writers there could be. A mumbling, astonishingly widely read boy genius who at the age of thirty-two was already editor to several of the writers I most admired, Henry took me under his wing.